Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Developing Valid Knowledge Scales

Developing Valid Knowledge Scales

Uploaded by

Burak BalıkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Developing Valid Knowledge Scales

Developing Valid Knowledge Scales

Uploaded by

Burak BalıkCopyright:

Available Formats

Developing Valid Knowledge Scales

Author(s): Jeffrey J. Mondak

Source: American Journal of Political Science , Jan., 2001, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Jan., 2001),

pp. 224-238

Published by: Midwest Political Science Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2669369

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Midwest Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to American Journal of Political Science

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Developing Valid Knowledge Scales

Jeffery J. Mondak Florida State University

Political knowledge is one of the or decades, students of mass politics have assessed how much citi-

central variables in research on mass zens know about politics, how people acquire and process political

political behavior, but insufficient information, whether political behavior varies as a function of dif-

attention has been given to the impli- ferences in knowledge levels, and whether various psychological mecha-

cations of alternate approaches to the nisms enable deficiencies in political knowledge to be overcome. Virtually

measurement of political knowledge. all research on public opinion, voting behavior, and media effects confronts

Two issues are considered here: (1) one or more of these questions. Because of the importance of knowledge as

survey protocol regarding "don't an analytical construct, several authors have explored issues in the mea-

know" responses and (2) item format. surement of political knowledge. This research has produced compelling

Data from the 1998 NES Pilot and a evidence that political awareness is best represented with data from survey

survey conducted in the Tallahassee batteries that measure factual political knowledge. Less insight has

metropolitan area are used to assess emerged, however, regarding the implications of how those knowledge bat-

alternate survey protocols. teries are constructed. Therefore, my purposes in this article are to identify

some of the key issues in the construction of knowledge batteries and to

demonstrate the consequences associated with use of alternate measure-

ment procedures.

Two issues in the measurement of political knowledge are addressed:

(1) survey protocol regarding "don't know" responses and (2) item format.

For both, possible changes in measurement procedures are discussed. Fol-

lowing this discussion, several potential liabilities associated with use of

new procedures are considered. In the last section of this article, I demon-

strate how the choice of knowledge measures affects hypothesis testing.

Throughout this article, alternate measurement procedures are evaluated

using data from two split-ballot surveys, the 1998 NES Pilot, and a survey

conducted in late 1998 and early 1999 in the Tallahassee metropolitan area.

Survey Protocol Regarding "Don't Know" Responses

When preparing items to be included on a mass survey, our initial task is to

take all necessary steps to maximize validity. It does us no good to draft a

survey that is easy for interviewers to administer and for respondents to

Jeffery J. Mondak is Professor of Political Science, Florida State University, Tallahassee,

FL 32306 (jmondak@garnet.acns.fsu.edu).

This article has benefited greatly from the comments and suggestions offered by

Damarys Canache, Aki Kamata, Mitch Sanders, the editor, and three anonymous re-

viewers. Some of the data analyzed here are from the 1998 NES Pilot; I wish to thank all

associated with this survey for including my items as part of the Pilot. Other data ana-

lyzed in this article are from a survey conducted by the Survey Research Laboratory at

Florida State University; I wish to thank Charles Barrilleaux, Belinda Davis, and Scott

Lamothe for their assistance with this survey.

American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 45, No. 1, January 2001, Pp. 224-238

?2001 by the Midwest Political Science Association

224

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DEVELOPING VALID KNOWLEDGE SCALES 225

complete if ambiguity exists regarding the meaning of dent offers a substantive answer, the probability that that

the resulting data. Some readers may view this admoni- person will answer correctly is greater than zero. On mul-

tion as merely a restatement of what we all already know tiple-choice items, even completely uninformed respon-

and accept. Emphasis on caution is warranted, however, dents will hit upon a few correct answers purely by

because it is a very simple matter when designing a sur- chance. When respondents differ in their propensity to

vey to make a seemingly innocuous decision that ulti- answer DK, respondents with identical levels of knowl-

mately brings serious repercussions. Precisely this has oc- edge will receive different scores on our knowledge bat-

curred in the measurement of political knowledge. teries. Consequently, when DKs are encouraged, knowl-

Common practice is to encourage "don't know" (DK) re- edge scores reflect two systematic factors: knowledge and

sponses on knowledge items. I will demonstrate that this propensity to guess.

practice risks yielding data that suffer systematic con- There are two ways that differences in the propensity

tamination by extraneous factors. Encouraging DKs to guess affect respondents' scores. First, uninformed re-

threatens validity. spondents who guess on objective items will answer

Surveys measuring political knowledge typically in- some correctly by chance. Hence, their scores will be in-

clude as many as four features that serve to encourage flated because they guessed. Second, some informed or

DKs. First, the preface used to introduce knowledge bat- partially informed respondents will answer DK. Because

teries in some cases explicitly informs respondents that these respondents could have answered correctly, their

DKs are welcome. The most prominent example on this scores will be deflated as a result of the decision not to

point comes from Delli Carpini and Keeter (1996, 305), offer a substantive answer. Research in psychometrics

who recommend that interviewers say to respondents demonstrates that both of these effects are common

that "many people don't know the answers to these ques- when DKs are encouraged.

tions, so if there are some you don't know just tell me The differential propensity to guess is a response set,

and we'll go on." Second, the wording of specific ques- or response style. Cronbach explained that "response sets

tions also encourages DKs. For instance, many knowl- are defined as any tendency causing a person consistently

edge items begin with the phrase "Do you happen to to make different responses to test items than he would

know... ." Third, survey interviewers usually receive in- have made had the same content been presented in a dif-

structions not to prompt the respondent for a substan- ferent form" (1946, 491). Cronbach also noted that "be-

tive answer on a knowledge item after the respondent has cause they permit persons with equal knowledge.. .to re-

expressed uncertainty. Fourth, many knowledge batteries ceive different scores, response sets always reduce logical

include items using a short-answer format, and this for- validity" (1946, 491). We face precisely this scenario with

mat tends to elicit a relatively high DK rate compared conventional measures of political knowledge: two re-

with closed-response formats such as multiple choice. spondents with identical knowledge levels will receive

Collectively, these efforts to encourage DKs seem to different scores if one respondent has a greater tendency

succeed quite well. For instance, Delli Carpini and Keeter than the other to answer DK; in this case, observed

(1996, 94) report data on fifty knowledge items. The data knowledge varies systematically even though actual

show that the average DK rate was over 31 percent. The knowledge is the same-a classic example of a response

DK rate on NES knowledge items has been similarly high set. On the NES, for instance, three knowledge questions

in recent years, and it is common for about twice as many used in recent years are multiple-choice items with two

respondents to answer DK as to answer incorrectly. choice options, and two other knowledge questions use a

Surveys protocols that encourage DKs would not be three-category multiple-choice format. This means that

problematic if we could be sure that all respondents react completely uninformed respondents who guess will re-

in exactly the same manner to these protocols. Unfortu- ceive average scores of 2.16, whereas uninformed respon-

nately, this is impossible to determine and it is almost dents who do not guess will receive scores of zero.

certainly not the case. For example, some respondents Knowledge is identical, but knowledge scores vary as a

who have no idea at all of the correct response nonethe- systematic function of the propensity to guess.

less may guess, whereas we know that many other re- Much of the early psychometric research on re-

spondents choose DK. Further, many respondents likely sponse sets was conducted to provide guidance for the

are somewhat sure, but not certain, that they know the construction of educational tests. Drawing on this re-

correct answer; in this scenario, it is probable that some search, writers in educational testing concur that the dif-

respondents choose DK and other respondents offer sub- ferential propensity to guess is a response set that con-

stantive answers. When a respondent answers DK, the taminates knowledge measures, thereby reducing validity

probability that the respondent will be given credit for a (e.g., Cunningham 1986; Mehrens and Lehmann 1984;

correct response is zero. In contrast, whenever a respon- Stanley and Hopkins 1972; Thorndike and Hagen 1969).

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

226 JEFFERY J. MONDAK

Stanley and Hopkins write, for instance, that "There couraged DKs. Specifically, the preface recommended by

would be no serious problem if all pupils of equal ability Delli Carpini and Keeter was read prior to the first knowl-

guessed with equal frequency, but it has been well estab- edge item, several of the items began with the phrase "Do

lished that there are great individual differences in the you know" or "Do you happen to know," and interviewers

tendency to guess on test items, that these differences are were instructed not to prompt respondents for substan-

reliable within a test, and that they are generally consis- tive answers if those respondents indicated uncertainty.

tent from one test to another" (1972, 142). The second version of each survey discouraged DKs. This

By encouraging DKs on knowledge items, our surveys version began with the preface "Here are a few questions

activate a response set, namely the differential propensity about the government in Washington. Many people don't

to guess. This means that knowledge scales suffer from know the answers to these questions, but even if you're

systematic contamination because personality factors re- not sure I'd like you to tell me your best guess." All items

lated to guessing (e.g., self-confidence, competitiveness, were phrased as direct questions (i.e., the wording "Do

risk-taking) influence knowledge scores. Elsewhere, I have you know" was not used). On the Tallahassee survey, re-

shown that personality does affect knowledge scores spondents who answered DK were prompted for substan-

(Mondak 2000), but I have come to view such evidence as tive responses. On the NES Pilot, DKs were recorded, and

unnecessary to make the case against encouraging DKs. then follow-up items were used in an attempt to convert

Encouraging DKs invites a response set that threatens va- initial DKs to substantive responses.

lidity. Where response sets can be eradicated, they should Four knowledge items were included on the NES Pi-

be. It is difficult to determine the precise threat to validity lot, and fourteen were asked on the Tallahassee survey.3

imposed by encouraging DKs, but this is irrelevant be- The DK rates for these questions are reported in Table 1.

cause there is no reason to tolerate any such threat (see On the NES Pilot, the overall DK rate was 20.46 percent

Cronbach 1946,487-488).1 for version one and 5.74 percent for version two. At-

Variance in the propensity to guess is neutralized as a tempts to convert DKs on version two succeeded in over

contaminating force if all respondents answer every item. 40 percent of cases, resulting in a revised DK rate of 3.35

When all respondents answer each item, scores vary as a percent. Thus, changing the preface to the battery and

function of one systematic factor, knowledge, and one the opening phrase of select items drove out nearly three-

unsystematic factor, chance. Research by Cronbach fourths of DKs, and many of the remaining DKs were

(1946, 1950) and Slakter (1968a, 1968b, 1969) provided converted to substantive answers in follow-up items. The

early support for the protocol of instructing test takers to ten items on the Tallahassee survey used a multiple-

first

guess. Subsequently, all of the major texts on educational

choice format. On these the overall DK rate was 13.74

testing have come to advocate that respondents answer percent on version one and 3.20 percent on version two,

every item (e.g., Cunningham 1986; Mehrens and meaning that, as on the NES, about three-fourths of DKs

Lehmann 1984; Nunnally 1972). were eliminated with the change in survey protocol. On

In survey research, discouraging DKs does not ensure the four short-answer items, the DK rate dropped only

that they will be eliminated. To assess the impact of the slightly, from 34.64 percent to 28.51 percent.4

change in protocol discussed here, I placed split-ballot In the classroom, students do not answer "don't

tests on two recent surveys, the 1998 NES Pilot, and a sur- know" on multiple-choice exams. Data from the NES

vey conducted under my supervision in the Tallahassee

metropolitan area.2 The first version of each survey en-

completions to refusals is exactly two to one. The completion rate,

calculated as completions divided by the sum of completions, re-

fusals, and unresolved cases (cases in which the telephone number

lIn the way of analogy, if someone begins hitting you in the head

was known to be that of a household, but where we were unable to

with a hammer, it will hurt, and you will wish for them to stop. It

obtain a completion or a refusal in twelve calls to the number) is

would be quite pointless to ponder how much the hammer hurts

49.6 percent.

because you would desire precisely the same outcome-and end to

the hammering-regardless of the answer. 3A fifteenth item was asked as part of the Tallahassee survey, but is

not included in current analyses. That item asked respondents

2Interviewing for the 1998 NES Pilot was conducted from Septem-

whether a government in which citizens elect members of a parlia-

ber 8 to November 3, with approximately 400 respondents drawn

ment is autocratic, authoritarian, or democratic. Correlations be-

from each of California, Georgia, and Illinois. The mean age of re-

tween this item and the other fourteen were extremely low, pre-

spondents is 43 years, and 56.8 percent of respondents are female.

sumably because only this item focused on subject matter that did

Interviewing for the Tallahassee survey began in mid-Novem-

not involve the U.S. government.

ber, 1998 and ended in late January, 1999. This survey was com-

pleted by 404 randomly selected residents of Leon County, with 40n the Tallahassee Survey, item 12 asks about Newt Gingrich.

interviews conducted by telephone using computer-assisted tele- Gingrich resigned as Speaker of the House while the survey was in

phone interviewing (CATI). The mean age of respondents is 41 the field. Respondents were awarded credit for a correct answer on

years; 54.0 percent of respondents are female; 71.6 percent of re- this item if their answers revealed that they understood that

spondents are white and 21.3 percent are black. The ratio of Gingrich was or had been the Speaker of the House.

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DEVELOPING VALID KNOWLEDGE SCALES 227

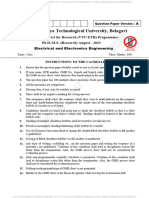

TABLE I Question Wording and "Don't Know" (DK) Rates When DKs Are Encouraged vs. Discouraged

Version One Version Two

DKs Encouraged DKs Discouraged

A. 1998 NES Pilot Study Percent DK

Preface: (Version one) Here are a few questions about government in Washington. Many [percent DK

people don't know the answers to these questions, so if there are some you don't know,

just tell me and we'll go on; (Version two) Here are a few questions about government in after prompt for

Washington. Many people don't know the answers to these questions, but even if you're substantive

not sure I'd like you to tell me your best guess. Percent DK response]

1. Who has the final responsibility to decide if a law is Constitutional or not ... 11.51 0.81

is it the President, Congress or the Supreme Court? [0.16]

2. And whose responsibility is it to nominate judges to the Federal Courts ... 16.67 1.94

the President, Congress, or the Supreme Court? [0.65]

3. (Do you happen to know) which party has the most members in the House 22.20 9.53

of Representatives in Washington? [6.46]

4. (Do you happen to know) which party has the most members in 31.44 10.66

the U.S. Senate? [6.14]

B.Tallahassee Survey

Preface: (Version one) Here are a few questions about the government in Washington.

Many people don't know the answers to these questions, so if there are some you don't

know, just tell me and we'll go on; (Version two) Here are a few questions about govern-

ment in Washington. Many people don't know the answers to these questions, but even if

you're not sure I'd like you to tell me your best guess.

1. (Do you know) who has the final responsibility to decide if a law is 12.25 1.00

Constitutional or not . . . is it the President, Congress, or the Supreme Court?

2. And whose responsibility is it to nominate judges to the Federal Courts . . . 15.20 3.50

the President, Congress or the Supreme Court?

3. (Do you happen to know) which party had the most members in the House 17.65 4.00

of Representatives in Washington before the election this month?

4. And (do you happen to know) which party had the most members in the 30.39 3.50

U.S. Senate before the election this month?

5. Which one of the parties is more conservative than the other at the national 7.88 4.02

level, the Democrats or the Republicans?

6. (Do you know) how much of a majority is required for the U.S. Senate and 11.27 3.50

House to override a presidential veto-a bare majority (50% plus one),

a two-thirds majority, or a three-fourths majority?

7. Suppose that a liberal senator and a conservative senator must vote on a bill 14.36 2.01

that would close down a federal regulatory agency. Which senator is more

likely to vote to close down the agency-the liberal senator, the conservative

senator, or would you say that both senators are equally likely to vote to close

the agency?

8. Which of the following does the U.S. government do to limit criticism of the 8.33 2.00

government in newspapers? Does the government require newspapers to be

licensed; does the government prohibit stories that are too critical of the

government from being published; or would you say that the U.S. government

has no regulations that limit political criticism in newspapers?

9. (Do you know) which of the following is the main duty of Congress-to write 11.76 6.00

legislation, to make sure that the president's policies are carried out properly;

or to watch over the states' governments?

10. How does the political system in the United States try to make sure that 7.88 2.50

political leaders are accountable to citizens-by having elections; by limiting

the president to two terms in office; or by having separate state courts and

federal courts?

11. (Do you know) what job or political office is currently held by Al Gore? 10.29 6.53

12. And what job or political office is currently held by Newt Gingrich? 17.73 14.50

13. And what about Trent Lott? 56.86 49.00

14. And finally, what about William Rehnquist? 53.69 44.00

Note. Phrases in parentheses were included only on the first version

N = 404.

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

228 JEFFERY J. MONDAK

Pilot and the Tallahassee survey reveal that the same is Item Format

not true for telephone interviews. Even when encour-

aged to answer every item, DKs accounted for over three Tests come in many forms: true/false, multiple-choice,

percent of responses on the multiple-choice questions. matching, short-answer, essay, and so on. Some of these,

Because these DKs suggest a firm resistance to guessing, such as matching tests and essay exams, are not appropri-

the uncorrected data invite contamination. Fortunately, ate for telephone surveys designed to measure political

DKs on multiple-choice questions can be eliminated

knowledge. But what are the strengths and weaknesses of

with a simple post hoc correction-random assignment

those formats that remain? Most survey questions asked

of DKs to the substantive choice categories. Kline (1986)

to measure political knowledge use either a short-answer

discusses this option for factual tests, and Rapoport

or a multiple-choice format. Fortunately, the properties

(1979) recommends use of this procedure to eliminate

of these formats have been studied exhaustively. This lit-

DKs on survey questions that measure attitudes. The

erature consistently emphasizes the positive attributes of

risk of response sets is nearly eliminated when DKs are

the multiple-choice format. Researchers have explored

distributed among the substantive categories because

numerous considerations regarding item format, but the

doing so, in effect, enters guesses on behalf of respon-

bottom line is that multiple-choice questions are highly

dents who would not do so themselves. After DKs are

resistant to response sets, meaning that use of multiple-

eliminated, all uninformed respondents have the same

choice questions maximizes our capacity to form valid

likelihood of answering an item correctly, meaning that

inferences regarding respondents' levels of knowledge.

knowledge scores no longer vary as a function of an ex-

On surveys, political knowledge batteries often in-

traneous factor, the differential propensity to guess.5

clude open-ended, short-answer items. Particularly com-

Data from the two split-ballot tests demonstrate

mon are questions that ask respondents to identify the

that it is possible to deter the vast majority of would-be

political offices held by various public figures. The NES

DK responses, particularly on items using a multiple-

includes items of this form focusing on the vice presi-

choice format. When we tell respondents that we want

dent, the Speaker of the House, the Chief Justice of the

them to answer our questions, they do.6 Use of the sur-

Supreme Court, and the president of Russia. Research in

vey protocol outlined here virtually eliminates the threat

psychometrics and educational testing demonstrates that

to validity posed by the guessing response set. Imple-

there are numerous liabilities associated with open-

mentation of this protocol requires four steps: (1) the

ended items such as these.

preface used to introduce knowledge batteries must en-

The first problem is that response sets are particularly

courage respondents to attempt to answer every item;

common with open-ended items. Consider a scenario in

(2) the wording of individual knowledge questions

which two respondents are asked to identify the position

should not invite DKs; (3) when respondents express

currently held by William Rehnquist. Both respondents

uncertainty, survey interviewers should encourage them

are relatively sure, but not certain, that Rehnquist is the

to attempt to offer substantive answers; and (4) on mul-

tiple-choice items, DKs should be converted to substan- Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. If the respondents

tive responses through random assignment to the avail- differ in their propensity to guess, then one will answer

able choice options. the item correctly and the other will choose DK-even

though their actual knowledge levels are identical. Had

the question been asked using a multiple-choice format

5Random assignment of DKs to the available choice options does

(e.g., "Is Rehnquist the Chief Justice of the Supreme

not fully eradicate the problem of differential propensities to

guess. For respondents who answered DK, this procedure mimics Court, the Secretary of State, or the Speaker of the

blind guessing. It could be, though, that had these respondents of- House?"), it is much more likely that both respondents

fered substantive answers, they would have outperformed chance.

would have answered correctly; the shy respondent who

Therefore, the combination of encouraging respondents to answer

every item and then eliminating DKs through post hoc correction thinks that Rehnquist is the Chief Justice of the Supreme

maximizes validity to the fullest extent reasonably possible, but I Court would have been reassured upon hearing that office

cannot claim that this procedure reaches the ideal-i.e., the ab- listed among the item's choice options.

sence of even the possibility of a response set.

This first problem implies that open-ended items do

6Elsewhere, Belinda Davis and I have assessed the impact that dis-

not support valid inferences regarding respondents'

couraging DKs has for observed knowledge levels (Mondak and

Davis forthcoming). We find that discouraging DKs increases knowledge levels, because some respondents who do

knowledge levels by a statistically significant margin for each know

of the correct answers on such items may nonetheless

several scales considered. Moreover, these increases exceed what choose DK. Data from the Tallahassee survey provide

blind guessing alone would predict, which implies that encourag-

ing DKs deters substantive answers by some informed or partially

evidence on this point. As we saw in Table 1, the effort to

informed respondents. discourage DKs was much less successful on the open-

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DEVELOPING VALID KNOWLEDGE SCALES 229

ended items than on the multiple-choice questions. But At first glance, the easy answer to the problem of

although only a relatively few DKs were discouraged, the subjective scoring is to award partial credit when partial

mean number of items answered correctly on the four- credit is due. In practice, though, matters are not so

question battery increased by nearly ten percent when simple. For this solution to work, we either would need

DKs were discouraged rather than encouraged, with the for survey instruments to include separate codes for ev-

mean rising from 2.24 to 2.46; DKs in this case masked ery possible partially correct response, or we would have

real knowledge. to instruct interviewers to record the respondent's full

Susceptibility to response effects is problematic, but answer. Both of these approaches would bring added cost

we could accept this limitation of the open-ended knowl- for researchers and an added complication for interview-

edge item if corrections were available. Unfortunately, the ers. Moreover, scoring still would be subjective. We might

second problem with the open-ended format is its resis- agree, for instance, that a respondent should be awarded

tance to correction. We can eradicate response effects by partial credit for identifying Rehnquist as "that guy with

eliminating DKs, but this is impossible with open-ended the fancy robe from Clinton's impeachment trial," but

items. As we have seen, DKs remain prevalent even when how much credit should we give? To avoid the problems

respondents are encouraged to offer substantive answers. of subjectivity, the most straightforward approach is to

Additionally, whereas we can substitute "guesses" for DKs avoid items that require subjective scoring.

on multiple-choice items by randomly assigning DKs to A fourth limitation is that tests using an open-ended,

the substantive choice categories, a comparable procedure or short-answer, format must restrict subject matter to

is not available for open-ended questions. In short, DKs basic facts. This format is not appropriate to test under-

on open-ended knowledge items pose a threat to validity, standing of concepts (Aiken 1988; Ebel and Frisbie 1986;

yet we can neither deter DKs nor eliminate them with Mehrens and Lehmann 1984; Stanley and Hopkins 1972;

post hoc corrections. Thorndike and Hagen 1969). If political sophistication

Subjective scoring constitutes a third problem with requires only mastery of names and dates, then we can

open-ended knowledge items. In educational testing, measure sophistication with open-ended items. But if

subjective scoring is one of the main criticisms of the political sophistication implies that a person understands

short-answer format (e.g., Cunningham 1986; Gronlund and can apply abstract concepts, then the open-ended

1998; Stanley and Hopkins 1972; Thorndike and Hagen format comes up short.

1969). What is the job or political office currently held by Numerous analysts concur that multiple-choice for-

William Rehnquist? On the NES, respondents are mats are superior to other forms of objective testing

awarded credit for a correct answer only if they indicate

(e.g., Ebel and Frisbie 1986; Gronlund 1998; Haladyna

that Rehnquist is the Chief Justice of the Supreme 1994).

Court.Many survey questions designed to measure po-

Respondents' answers are coded as incorrect if theylitical

indi-knowledge use a two-category (e.g., which party

cate, for example, that Rehnquist is "on the Supreme controls the U.S. House?) or three-category (e.g., whose

Court" "a judge'" "that guy with the fancy robe from responsibility is it two determine whether a law is Con-

Clinton's impeachment trial," or "the King of Canada." stitutional-the president, the Congress, or the Supreme

The first three of these "incorrect" responses clearly re- Court?) multiple-choice format. Items such as these suf-

veal -greater knowledge regarding Rehnquist's identity fer none of the limitations associated with open-ended

than does the fourth, and thus validity is threatened questions. What is most important is that multiple-

when all incomplete and incorrect answers are coded choice tests are not susceptible to response sets. When

identically. This is not a trivial problem. Delli Carpini DKs are discouraged, multiple-choice questions mea-

and Keeter (1996) report that respondents often exhibit sure only one systematic factor, knowledge. Cronbach

partial understanding on open-ended questions. On the (1946) offered a series of recommendations for avoiding

Tallahassee survey, interviewers were given a separate re- response sets, the first of which was that tests should use

sponse category to record partially correct answers on the multiple-choice format. Cronbach subsequently re-

the four identification items. Overall, five percent of examined the multiple-choice format to determine

answers were identified as being partially correct, with whether there were any conditions in which response

most of these responses recorded on the two most diffi- sets could be detected: "Our attempt to find a response

cult items, those concerning Trent Lott and William set in the multiple-choice test was almost completely

Rehnquist. Interviewers recorded 280 correct answers on unsuccessful. A set was extracted, and that a set with

those two questions, 62 incorrect answers, and 54 par- little reliability, only when the test was applied to sub-

tially correct answers; hence, the level of misinformation jects for whom it was unreasonably difficult" (1950, 22).

would have been overstated by nearly double had all par- Subsequent writers have concurred that multiple-choice

tially correct answers been coded as incorrect. items are more resistant to response sets than all other

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

230 JEFFERY J. MONDAK

objective test formats (e.g., Aiken 1988; Mehrens and slightly longer in Tallahassee when DKs were discour-

Lehmann 1984; Nunnally 1972). aged, but slightly shorter on the NES Pilot. The differ-

When multiple-choice questions are used to mea- ences in both instances are substantively minor and sta-

sure political knowledge, how many choice options tistically insignificant.

should be offered? In some cases, the number of choice By definition, open-ended questions lack predeter-

options is dictated by the substantive content of the mined choice options. Hence, the use of open-ended

question, such as when we ask respondents which party rather than closed formats may add to survey length both

controls the U.S. House. When it is possible to include because it takes respondents longer to answer open-

three or more choice options, the use of three options is ended items and because it takes interviewers longer to

appropriate. In theory, items with four or five choice op- record the answers. The added time associated with use

tions will yield more reliable data than items with three of open-ended items would increase if efforts were made

options, but this does not hold in practice. First, Delli to account for partial information. Consequently, the

Carpini and Keeter (1993) point out that use of a large move to replace open-ended knowledge questions with

number of response options is impractical during tele- items using a multiple-choice format may result in a de-

phone interviews. Second, the empirical superiority of crease in survey length.

the three-option multiple-choice item has been long rec- Survey researchers have long been concerned that

ognized in psychometrics, dating back to an influential knowledge items may make respondents feel uncomfort-

study by Tversky (1964). Subsequent research has con- able. However, recent evidence suggests that this fear is

tinued to corroborate Tversky's position (e.g., Haladyna unfounded. Delli Carpini and Keeter (1996) asked their

and Downing 1993; Landrum, Cashin and Theis 1993).7 respondents an extensive knowledge battery, one far

longer than those included on most surveys, yet respon-

dents did not find the survey to be disconcerting. If, as dis-

cussed here, survey protocol is reversed so that DKs are

Competing Considerations discouraged rather than encouraged, I expect no effect on

interview rapport or respondent morale. On one hand,

The two points discussed above potentially provide some respondents may prefer answering DK to answering

means to improve the quality of political knowledge incorrectly; discouraging DKs could make these respon-

scales. However, competing considerations may affect thedents uncomfortable. But on the other hand, some re-

decision regarding whether to implement new measure- spondents may find the current approach, which, in es-

ment procedures. Four matters require attention: that sence, is to tell respondents that there is no shame in

changes in knowledge batteries may add to the financial ignorance, to be patronizing. Relevant data from the NES

cost of survey research, that changes may adversely affect Pilot are reported in section B of Table 2. NES interview-

interview rapport, that changes may reduce scale reliabil- ers answered several questions about respondents. In no

ity, and that new procedures may lead us to measure a instance did these ratings vary when DKs were discour-

different-and less interesting-form of knowledge than aged rather than encouraged. A final point to consider re-

the one tapped using current approaches. garding interview rapport is that the switch from open-

The central procedural revision discussed in this ar- ended items to multiple-choice questions is likely to have

ticle is that DKs should be discouraged rather than en- a positive effect. Open-ended questions are inherently

couraged. Intuitively, this change may add to survey more difficult than closed-format questions, and these

length because respondents who previously would have questions routinely elicit high DK rates. By eliminating

unthinkingly answered DK now will be encouraged to such questions, respondents no longer will be forced to

deliberate. This intuition is incorrect. The 1998 NES Pi- make the uncomfortable admission of political ignorance.

lot and the Tallahassee survey both included timers. Data The next consideration is the possible impact of new

reported in section A of Table 2 indicate that discourag- survey procedures on reliability. Encouraging DKs may

ing DKs did not increase survey length. Interviews were increase reliability, a point noted by Delli Carpini and

Keeter as part of their explanation for why, in their view,

DKs should encouraged: "some specialists recommend

7A key finding in this literature is that the theoretical advantages of

four-option and five-option items are rarely achieved in practice, telling achievement test subjects to guess in order to

and thus the gain in reliability over three options is minimal (e.g., minimize biases arising from differential propensities to

Downing 1992). The central problem, which is surely familiar to

guess. We concluded, however, that the unreliability in-

readers who have written multiple-choice tests, is that it is often

quite difficult to think of more than two truly plausible incorrect troduced by guessing was the more serious problem. Ac-

answers (or "distractors" in the language of educational testing). cordingly, we discouraged guessing..." ( 1993, 1 183). As

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DEVELOPING VALID KNOWLEDGE SCALES 231

TABLE 2 Knowledge Items, Survey Length and Respondent Morale

Average DKs DKs

A. Survey Length Length Encouraged Discouraged Sig.

Tallahassee Survey 23:00 22:54 23:06 0.74

1998 NES Pilot 47:52 49:16 46:34 0.27

B. Respondent Morale Overall DKs DKs

(all data from 1998 NES Pilot) Percentage Encouraged Discouraged Sig.

Respondent appeared confused by questions 5.24 4.81 5.64 0.52

Respondent expressed doubt or embarrassment

over general lack of knowledge 5.82 5.84 5.80 0.97

Respondent expressed doubt or embarrassment

over lack of specific knowledge (e.g., candidate

names, issues) 10.89 10.31 11.43 0.53

Respondent was stressed or agitated by

the interview 3.08 3.09 3.06 0.97

we have seen, the biases to which Delli Carpini and ability is affected by use of alternate protocols. Research

Keeter refer threaten our capacity to elicit valid infer- on attitudinal measures has explored this issue and has

ences from knowledge data. In other words, to discour- found that inclusion of "no opinion" options does not

age guessing is to seek reliability at the expense of valid- increase reliability (see Krosnick 1999 for a review).

ity. Cronbach explained this point well, noting that To explore the effect on reliability for knowledge

"there is no merit in enhancing test reliability unless va- measures, three scales were constructed using data from

lidity is enhanced at least proportionately" (1950, 22). the NES Pilot and the Tallahassee survey. The first scale

The possible inverse relationship between reliability includes the four NES items; the second scale includes

and validity on political knowledge scales is not the the five items recommended by Delli Carpini and Keeter;

product of coincidence. When DKs are encouraged, finally, the last scale includes all ten multiple-choice

knowledge scales systematically tap two constructs, items. Reliability statistics are computed for three ver-

knowledge and propensity to guess. Both of these sys- sions of each scale: (1) DKs encouraged; (2) DKs dis-

tematic factors contribute to reliability. In the extreme couraged; and (3) DKs discouraged and post hoc correc-

case, for instance, we will observe perfect correlation for tions made to eliminate all obtained DKs. Reliability is

respondents who always answer DK. As explained above, expected to be highest for the first version of each scale

response sets are minimized or even eradicated when and lowest for the last. The key question centers on reli-

tests use a multiple-choice format and respondents are ability levels for the third version of each scale; that is,

directed to answer every item. If response sets artificially what are the consequences for reliability when validity is

inflate reliability, it follows that reliability will tend to de- maximized?

cline in the absence of response sets because one of two Results are depicted in Table 3. Efforts to reduce sys-

systematic sources of variance is removed. A drop in reli- tematic error bias attenuate alpha scores, especially for

ability is especially to be expected on multiple-choice the four-item NES scale. However, it is important to keep

tests because blind guessing increases random measure- in mind that Cronbach's alpha is not actually a reliability

ment error (Cronbach 1946, 1950). In other words, a sys- coefficient, but rather the lower bound of reliability

tematic threat to validity (i.e., the differential propensity(Hambleton, Swaminathan, and Rogers 1991; Lord

to guess) is exchanged for unsystematic variance. Validity 1980). Researchers in psychometrics have devised nu-

increases, but reliability decreases. merous alternate reliability formulas, although no con-

The trade-off between reliability and validity raises sensus has emerged in favor of any single approach (e.g.,

the question of how much reliability is reduced when we Hambleton, Swaminathan, and Rogers 1991; Lord 1980;

use survey procedures that guard against response sets. Lord and Novick 1968; Sijtsma and Molenaar 1987). As

Delli Carpini and Keeter pointed to a possible decline in an alternate to Cronbach's alpha, I calculated Item Re-

reliability as a reason for why DKs should be encouraged, sponse Theory (IRT) reliability coefficients for version C

but they offered no evidence regarding how greatly reli- of each scale in Table 3 using the item analysis program

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

232 JEFFERY J. MONDAK

TABLE 3 Reliability Analysis for Knowledge Scales

Number of Cronbach's Alpha

Scale Version Items [Item response theory reliability index]

1. 1998 NES Pilot A. DKs encouraged 4 0.683

B. DKs discouraged 4 0.610

C. DKs discouraged, post hoc 4 0.461

corrections added [0.675]

2. Delli Carpini and Keeter A. DKs encouraged 5 0.647

five-item scale B. DKs discouraged 5 0.595

C. DKs discouraged, post hoc 5 0.560

corrections added [0.632]

3. 10-item multiple-choice A. DKs encouraged 10 0.768

scale B. DKs discouraged 10 0.744

C. DKs discouraged, post hoc 10 0.710

corrections added [0.742]

Note: Data for the first scale are from the 1998 NES Pilot (see Table 1); data from the second and third scales are from the Tallahassee Survey (see

Table 1). Version C of each scale used data from version B, with DKs eliminated through random assignment to the substantive response categories.

Bilog 3 (see Lord and Novick 1968; Mislevy and Bock in information that is highly accessible, whereas the new

1990). These estimates exceed alpha scores, and the in- measurement procedures discussed here-especially dis-

crease for the NES scale is substantial. This is not surpris- couraging DKs-would have the effect of inducing re-

ing given that the IRT reliability index is obtained from spondents to search their long-term memories. This sug-

the three-parameter logistic model; the three-parameter gestion has merit at first glance, but deeper inspection

model accounts for both guessing and variance in item reveals several analytical and evidentiary flaws.

difficulty, factors that limit alpha scores.8 First, I am aware of no research that indicates that en-

Efforts to increase validity may have the side effect ofcouraging DKs constitutes a valid means to measure ac-

producing a slight reduction in reliability, but this should cessible, as opposed to stored, information. Delli Carpini

not dissuade use of new survey protocols. First, the boost and Keeter-who suggest that DKs should be encouraged

in reliability brought by encouraging DKs is artifactual. as a means to increase reliability-argue that knowledge

Encouraging DKs increases reliability by contaminating stored in long-term memory is the construct of interest,

scales with systematic error. Second, the impact on reli- and that data from knowledge batteries on opinion sur-

ability is minor. Alpha coefficients, which mark the lower veys measure this construct. Second, available evidence

bound of reliability, may drop noticeably with use of im- raises serious questions regarding the validity of knowl-

proved survey procedures, but alternate reliability mea- edge data as indicators of accessible information. Delli

sures show that the impact of survey protocol on reliabil- Carpini and Keeter report that many respondents expend

ity is minimal. Third, reduced reliability in the current a great deal of effort in trying to answer knowledge items

case is not of sufficient magnitude to adversely affect hy- correctly-even when DKs are encouraged. I have ob-

pothesis testing. To the contrary, we will see below that served similar behavior when monitoring survey inter-

the impact of knowledge as an independent variable of- views with knowledge batteries. Hence, when DKs are en-

ten is understated because of the systematic flaws charac- couraged, some respondents nonetheless do search their

teristic of current measurement practices. long-term memories. If other respondents do not, then

The final competing consideration concerns the pos- this means that encouraging DKs causes us to measure

sibility that political scientists should be most interested different things for different people: stored knowledge for

some, accessible knowledge for others.

8It is technically possible to calculate IRT reliability estimates for

Third, even if it were the case that encouraging DKs

the other two versions of each knowledge scale, but it would be in-

correct to do so. IRT imposes the assumption that only a single increases the likelihood that we will measure accessible

construct is being measured, or, at minimum, that the construct knowledge, any virtue associated with doing so must be

under consideration is the dominant factor affecting test perfor-

weighed against the threat to validity imposed by the

mance (Hambleton and Swaminathan 1985; Hambleton,

Swaminathan, and Rogers 1991). That assumption is violated guessing response set. When DKs are encouraged, differ-

when no efforts are made to discourage or correct for DKs. ences in the propensity to guess produce systematic er-

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DEVELOPING VALID KNOWLEDGE SCALES 233

ror. We should be highly reluctant to accept such error ists). Respondents also were asked their views on five

absent clear evidence that the protocol that generates questions of policy.9 A familiar two-part hypothesis for

this error constitutes our only means to measure acces- opinion data such as these holds, first, that attitudes will

sible knowledge. vary as a function of ideology, and, second, that ideology

Fourth, the data reported in Table 2 are inconsistent will exert the strongest impact on opinion among the

with the claim that discouraging DKs causes respondents most sophisticated respondents (i.e., respondents with the

to search their long-term memories more exhaustively. If highest knowledge scores). To test such a hypothesis, feel-

one protocol measures accessible knowledge and the ing thermometer scores and policy items are modeled as a

other measures stored knowledge, then split-ballot tests function of ideology, knowledge, and their interaction.10

should have produced differences in survey length. How- If discouraging DKs increases the validity of knowl-

ever, as noted above, no such differences exist. edge scales, then we should observe sharper knowledge x

A final response to the question of accessible vs. ideology interactions. Suppose that, in reality, ideology

stored knowledge is that political scientists should be has no effect on opinion among the least-knowledgeable

most interested in measuring knowledge in the form that respondents. When DKs are encouraged, the people we

people use it. This matter receives extensive discussion identify as politically ignorant include some knowledge-

below, but that discussion can be summarized quite sim- able respondents who answered DK on our knowledge

ply: the observed impact of political knowledge on the items. The positive relationship between ideology and

structure of mass opinion is greatest when knowledge is opinion for these respondents would lead us to conclude

measured in accordance with the two-part protocol dis- -wrongly-that ideology has some impact on the atti-

cussed here. tudes of even the most unsophisticated citizens.

Researchers are right to consider factors other than Coefficients reported in Table 4 are consistent with

validity when designing knowledge measures, but no fac- the reasoning I have advanced. Knowledge effects are

tors provide grounds to reject the revisions in measure- detected for eleven of the thirteen dependent variables.

ment procedure delineated above. Discouraging DKs and In ten of these eleven cases, the knowledge x ideology

eliminating open-ended items will have no negative ef- interaction is greater when DKs are discouraged rather

fects in terms of survey cost, interview rapport, or the ca-

than encouraged. In seven cases, the differences are sta-

pacity to measure meaningful forms of knowledge. tistically significant. Using a conventional knowledge

scale constructed with items on which DKs were en-

couraged, we would have understated the impact of

knowledge on appraisals of Bill Clinton, Newt Gingrich,

The Performance of Knowledge and opinion regarding cuts in social services, and we

as an Independent Variable would have missed entirely the effect of knowledge on

opinion regarding Christian Fundamentalists, pro-life

Political knowledge scales have been used widely as inde- groups, abortion rights, and affirmative action in uni-

pendent variables in research on numerous aspects of versity admissions.

mass political behavior. Full assessment of the effects of Figure 1 reports estimates for the four feeling ther-

changes in measurement procedures on the performance mometers for which disparate results were detected, and

of knowledge scales is well beyond the scope of this ar-

ticle. Nonetheless, a brief review of available evidence re- 9The first item is a seven-point scale concerning whether respon-

veals that use of modified knowledge scales can have a dents feel that social services should be cut as a way to reduce gov-

substantial impact on the conclusions derived in empiri- ernment spending; there were two variants of this item, but I col-

lapsed the data for the analyses reported below. The second item is

cal research. Two tests will be discussed here: whether the

a four-point scale that taps the extent to which respondents sup-

influence of ideology on opinion about political leaders, port a two-year cap on welfare benefits. The third item is a four-

groups, and policy issues varies as a function of political category measure of support for abortion rights. The fourth item

is a four-point scale concerning support for affirmative action in a

knowledge and whether knowledge affects levels of po-

company that has a history of discrimination. The final item is a

litical tolerance. dichotomous measure of support for affirmative action in univer-

Six feeling thermometer items were posed to all re- sity admissions.

spondents on the 1998 NES Pilot (Bill Clinton, Newt I0In the models estimated here, control variables include age, edu-

Gingrich, labor unions, pro-life groups, environmental cation, sex, party identification, and, for the group dependent vari-

ables, group membership. Control variables were held at constant

protection groups, and conservative religious groups),

values (means or modes as appropriate) for all calculations dis-

and all respondents were asked one of two variants of a cussed below. Ideology was measured on the NES pilot using a

seventh item (the religious right/Christian fundamental- split-ballot design; data from the two versions are collapsed here.

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

234 JEFFERY J. MONDAK

TABLE 4 The Impact of Encouraging vs. Discouraging DKs on the Performance of Knowledge

as an Independent Variable

DKs Encouraged DKs Discouraged

Unstandardized Unstandardized

regression coefficient: regression coefficient:

ideology x knowledge ideology x knowledge N

A. 1998 NES Pilot Feeling Thermometers

President Bill Clinton -2.30*** _4.59*** D 1002

(0.65) (1.01)

House Speaker Newt Gingrich 2.08*** 3.99*** C 946

(0.54) (0.79)

Labor unions such as the AFL-CIO -0.72 -1.22 941

(0.54) (0.84)

Pro-life groups such as the National Right to Life Committee 0.71 3.98*** B 939

(0.66) (1.04)

Environmental protection groups such as the Sierra Club -1.68** -1.49# 906

(0.54) (0.84)

Conservative religious groups such as the Christian Coalition 2.86*** 3.83*** 926

(0.58) (0.94)

The Religious Right 2.90** 4.61*** 429

(0.92) (1.45)

Christian Fundamentalists 1.06 5.96*** B 419

(0.81) (1.32)

B. 1998 NES Pilot Policy Preference Items

Services vs. spending -0.11 * -0.27*** c 882

(0.04) (0.06)

Two-year limit on welfare (ordered logit estimates) 0.06 0.08 975

(0.04) (0.07)

Legal abortion (ordered logit estimates) -0.05 Q0.34*** A 996

(0.04) (0.08)

Affirmative action in hiring (ordered logit estimates) -0.13** -0.19** 961

(0.04) (0.07)

Affirmative action in universities (binomial logit estimates) -0.07 -0.28*** c 965

(0.05) (0.08)

Note. Estimates are from OLS regression models unless otherwise indicated. Standard errors are in parentheses.

***p <.001 **p < .01 *p <.05 #p <.10

Superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences in coefficients for column one vs. column two contrasts: Ap < .0

Dp < .10

Figure 2 reports estimates for policy attitudes.11 The solid respondents who engage in blind guessing. On the left

lines depict estimates for respondents who answered all side of each figure, the differences between the slopes of

four knowledge items correctly, whereas the dashed lines the solid and dashed lines are modest. Even when knowl-

represent effects with 1.67 knowledge items answered edge is low, political attitudes appear to contain at least

correctly-the expected value on the knowledge scale for some ideological structure. Based on these data, we

would conclude that ideology generally matters for all re-

l'In Figure 2, the vertical axis in the second and third charts in spondents, but that it matters somewhat more for the

each column is the estimated logit derived from the ordered logit most knowledgeable. A different picture emerges on the

and binomial logit models. Similar results are obtained when I

graph predicted probabilities rather than estimated logit. However,

because the underlying construct in each of these cases is continu- results as they pertain to that construct rather than as they pertain

ous (i.e., respondents' attitudes on issues), it is preferable to depict to an artificially imposed metric (see Berry 1999).

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DEVELOPING VALID KNOWLEDGE SCALES 235

FIGURE 1 The Interactive Effect of Knowledge and Ideology

on Feeling Thermometer Scores

DKs Encouraged DKs Discouraged

100 100

President Clinton President Clinton

80 - 80-

60 -6

40 40-

20 -2

0 ,

100 100

Speaker Gingrich Speaker Gingrich

80 80

60 -60-

40 - 40

20 - 20 -

0* C

100 100

Pro-life groups Pro-life groups

80 80

60 - 60 -

40 -40-

20 20

0 l

100 100

Christian Fundamentalists Christian Fundamentalists

80 80

60 -60-

40 -- 40-

20 -20-

0 C

Strong Strong Strong Strong

Liberal Cons. Liberal Cons.

High Knowledge (4) Low Knowledge (1.67)

Source: Table 4a.

right side of each figure. There, the dashed lines are rela- Tests conducted using NES data demonstrate that

tively flat, indicating that ideology does not contribute to discouraging DKs substantially improves the perfor-

the structure of opinion for fully uninformed respon- mance of knowledge scales, but these tests provide no

dents. Using knowledge scales constructed with items on evidence relevant to the question of item format. Unfor-

which DKs were discouraged, we would conclude that tunately, resource constraints dictated that the local sur-

ideology exerts strong influence on the opinions of so- vey focus almost exclusively on the measurement of po-

phisticated respondents and no influence on the opin- litical knowledge, meaning that multiple dependent

ions of the unsophisticated. variables are not available for additional tests. The one

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

236 JEFFERY J. MONDAK

FIGURE 2 The Interactive Effect of Knowledge and Ideology

on Policy Attitudes

DKs Encouraged DKs Discouraged

7 7

6 Serv

5 5 -

4 - 4-

3 -3-

2- 2-

1 ,, 1

Support Abortion Rights Abortion Rights

Oppose 1L 1_

Support Affirmative Action in Affirmative Action in

Universities Universities

Oppose l l_l_,1

Strong Strong Strong Strong

Liberal Cons. Liberal Cons.

High Knowledge (4) Low Knowledge (1.67)

Source: Table 4b.

variable for which data are available is political toler- for scales constructed in a manner consistent with the re-

ance. Delli Carpini and Keeter (1996) show that toler- vised procedures discussed in this article. Coefficients in

ance increases as a function of political knowledge, a the first row reflect the impact of discouraging DKs. As

finding that also has been reported elsewhere (e.g., was the case with several of the NES attitudinal measures,

Marcus et al. 1995). Using data from the local survey, we knowledge appears to be unrelated to tolerance when

can explore whether how knowledge is measured affects DKs are encouraged, whereas a strong effect emerges

the conclusions we derive regarding the impact of when DKs are eliminated.13

knowledge on tolerance.

The tolerance measure is a four-category ordinal 13 Although discouraging DKs strengthens knowledge effects in the

item, and thus data are analyzed using ordered logistic tests reported here, I do not expect this same result to hold for all

dependent variables. On dependent variables on which scores are

regression.12 Results of two contrasts are reported in

subject to exaggeration by respondents-e.g., participation, turn-

Table 5. For each test, the second column indicates effects out, and media attentiveness-knowledge scales contaminated by

a guessing response set likely will produce stronger effects than will

12 The tolerance data were obtained as part of a 2 x 2 question uncontaminated scales. In this case, however, the identified

wording experiment. Data from the four cells are collapsed in the "knowledge" effect partly represents the impact of personality, not

analyses conducted here. The ordered logit models included three knowledge; that is, the same people who refuse to admit political

dummy variables to distinguish the four cells of the experiment, ignorance also refuse to admit a lack of political participation. For

along with controls for age, sex, race, education, and ideology. additional discussion of this point, see Mondak (2000).

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

DEVELOPING VALID KNOWLEDGE SCALES 237

TABLE 5 Knowledge and Political Tolerance

A. Discouraging DKs

Contrast: Delli Carpini and Keeter five-item scale, DKs encouraged vs. DKs discouraged 0.08 0.47*

(0.13) (0.14)

B. Elimination of Open-ended Items

Contrast: Four-item open-ended scale, DKs discouraged, no additional corrections vs. 0.43* 0.52**

DKs discouraged, plus corrections for partial information (0.14) (0.14)

Note: Cell entries are ordered logistic regression coefficients. The dependent variable is a

included in the models are age, sex, education, race, and ideology.

**p < .001 *p < .01

To test the performance of open-ended items, I use ferent knowledge scores for respondents whose actual

data for which DKs were discouraged, and contrast the knowledge levels are identical. In short, encouraging DKs

performance of scales with and without corrections for infuses knowledge scales with systematic error.

partial information. Both scales yield significant effects, An additional matter compounds the problems as-

with the strongest effect obtained when credit was sociated with encouraging DKs. Many items used to

awarded for partially correct responses. These results measure political knowledge are open-ended questions

support a mixed assessment of open-ended knowledge that ask respondents to identify various political leaders.

questions. At least for tolerance, it is apparently unneces- Such items are problematic because they are resistant to

sary to abandon open-ended items in favor of multiple- efforts to discourage and correct for DKs. Open-ended

choice items. Nonetheless, the inherent subjectivity of items may bring further imprecision if partially correct

open-ended items remains problematic. Only five per- responses are handled improperly. For instance, the

cent of responses on these questions were deemed to be norm on the NES is to code all partially correct answers

partially correct, and yet the link between knowledge and as incorrect, a practice that inherently undercuts our ca-

tolerance sharpened noticeably with use of corrected pacity to distinguish uninformed and partially informed

data. Provided that DKs are discouraged and partial respondents.

credit is awarded when appropriate, the drawback associ- Straightforward changes in survey procedure can be

ated with open-ended items is one of logistics, not valid- implemented to address the shortcomings associated

ity. These items can function satisfactorily, but their ad- with current approaches. Analyses reported here show

ministration is cumbersome, costly, and imprecise that the guessing response set produced when DKs are

relative to multiple-choice items. encouraged can be greatly minimized by encouraging re-

spondents to answer every knowledge item. On multiple-

choice items, post hoc corrections can be used to elimi-

nate any remaining DKs. The limitations of open-ended

Conclusions items can be avoided completely if knowledge batteries

include only two- and three-category multiple-choice

Analyses conducted here have sought to demonstrate questions.

that current survey protocol with respect to the measure- The risk that implementation of new survey proce-

ment of political knowledge brings imprecision, that dures may result in unintended adverse consequences ap-

straightforward and inexpensive changes in procedure pears minimal. Diagnostic tests conducted in this article

can reduce this imprecision, and that implementation of demonstrate that efforts to improve validity bring no dis-

such procedures can improve our ability to test hypoth- cernible cost in terms of interview length, survey rapport,

eses concerning citizens' levels of political competence. or scale reliability. To the contrary, the most important

Our capacity to derive valid inferences from analyses consequence identified here is positive. Because impreci-

based on survey data presupposes that the indicators we sion in measurement will tend to attenuate the observed

use measure only the constructs under consideration. For effect of an independent variable, current measures of po-

political knowledge, this fundamental requirement cur- litical knowledge muddle hypothesis testing. The analyses

rently is not met. The most significant issue is that, by reported here show, for instance, that the extent to which

encouraging DKs on knowledge items, we produce data ideological structure in mass opinion varies as a function

plagued by a guessing response set. The guessing re- of political knowledge is substantially understated when

sponse set means that we may observe substantially dif-

DKs are encouraged. Likewise, the impact of knowledge

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

238 JEFFERY J. MONDAK

on tolerance is understated when DKs are encouraged and Hambleton, Ronald K., H. Swaminathan, and H. Jane Rogers.

1991. Fundamentals of Item Response Theory. Newbury Park,

when partially correct responses on open-ended items are

Calif.: Sage.

not coded appropriately.

Kline, Paul. 1986. A Handbook of Test Construction. London:

Political knowledge has attained the status of a cor-

Methuen & Co.

nerstone construct in research on political behavior, but

Krosnick, Jon A. 1999. "Survey Research." Annual Review of

it has done so despite constraints imposed by suboptimal Psychology 59:537-567.

measurement procedures. The exploratory analyses re- Landrum, R. Eric, Jeffrey R. Cashin, and Kristina S. Theis. 1993.

ported in this article suggest that the tangible conse- "More Evidence in Favor of Three-Option Multiple-Choice

Tests." Educational and Psychological Measurement 53:771-

quences of those constraints may be substantial. Hence,

778.

as progress continues in the effort to develop valid

Lord, Frederic M. 1980. Applications of Item Response Theory to

knowledge measures, evidence regarding the substantive

Practical Testing Problems. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence

importance of political knowledge can be expected to ac- Erlbaum Associates.

cumulate at an increasing pace. Lord, Frederic M., and Melvin R. Novick. 1968. Statistical Theo-

ries of Mental Test Scores. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Manuscript submitted June 9, 1999. Marcus, George E., John L. Sullivan, Elizabeth Theiss-Morse,

Final manuscript received June 8, 2000. and Sandra L. Wood. 1995. With Malice Toward Some: How

People Make Civil Liberties Judgments. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Mehrens, William A., and Irvin J. Lehmann. 1984. Measure-

References ment and Evaluation in Education and Psychology. 3rd ed.

New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Aiken, Lewis R. 1988. Psychological Testing and Assessment. 6th Mislevy, Robert J., and R. Darrell Bock. 1990. Bilog 3: Item

ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Analysis and Test Scoring with Binary Logistic Models. 2nd

ed. Mooresville, Indiana: Scientific Software Inc.

Berry, William D. 1999. "Testing for Interaction in Models with

Binary Dependent Variables." Political Methodology Work- Mondak, Jeffery J. 2000. "Reconsidering the Measurement of

ing Paper Archive, http://polmeth.calpoly.edu. Political Knowledge." Political Analysis 8:57-82.

Cronbach, Lee J. 1946. "Response Sets and Test Validity." Educa- Mondak, Jeffery J., and Belinda Creel Davis. Forthcoming.

"Asked and Answered: Knowledge Levels When We Won't

tional and Psychological Measurement 6:475-694.

Take 'Don't Know' for an Answer." Political Behavior.

Cronbach, Lee J. 1950. "Further evidence on Response Sets and

Test Design." Educational and Psychological Measurement Nunnally, Jum. 1972. Educational Measurement and Evaluation.

10:3-31.

2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Cunningham, George K. 1986. Educational and Psychological Rapoport, Ronald B. 1979. "What They Don't Know Can Hurt

You." American Journal of Political Science 23:805-815.

Measurement. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Delli Carpini, Michael X., and Scott Keeter. 1993. "Measuring Sijtsma, Klaas, and Ivo W. Molenaar. 1987. "Reliabillity of Test

Political Knowledge: Putting First Things First." American Scores in Nonparametric Item Response Theory." Psycho-

metrika 52:79-97.

Journal of Political Science 37:1179-1206.

Delli Carpini, Michael X., and Scott Keeter. 1996. What Ameri- Slakter, Malcolm J. 1968a. "The Effect of Guessing Strategy on

can Know About Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven: Objective Test Scores." Journal of Educational Measurement

5:217-222.

Yale University Press.

Downing, Steven M. 1992. "True-False and Alternative-Choice Slakter, Malcolm J. 1968b. "The Penalty for Not Guessing."

Formats: A Review of Research." Educational Measurement: Journal of Educational Measurement 5:141-144.

Issues and Practices 11:27-30. Slakter, Malcolm J. 1969. "Generality of Risk Taking on Objec-

Ebel, Robert L., and David A. Frisbie. 1986. Essentials of Edu- tive Examinations'" Educational and Psychological Measure-

ment 29:115-128.

cational Measurement. 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.:

Prentice-Hall, Inc. Stanley, Jullian C., and Kenneth D. Hopkins. 1972. Educational

Gronlund, Norman E. 1998. Assessment of StudentAchievement. and Psychological Measurement and Evaluation. Englewood

6th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Thorndike, Robert L., and Elizabeth Hagen. 1969. Measure-

Haladyna, Thomas M. 1994. Developing and Validating Mul-

tiple-Choice Items. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum. ment and Evaluation in Psychology and Education. 3rd ed.

New York: Wiley.

Haladyna, Thomas M., and Steven M. Downing. 1993. "How

Many Options is Enough for a Multiple-Choice Test Item?" Tversky, Amos. 1964. "On the Optimal Number of Alternatives

Educational and Psychological Measurement 53:999-10 10. at a Choice Point." Journal of Mathematical Psychology

1:386-391.

Hambleton, Ronald K., and Hariharan Swaminathan. 1985.

Item Response Theory: Principles and Applications. Boston:

Kluwer-Nijhoff Publishing.

This content downloaded from

193.255.97.58 on Mon, 24 Jun 2024 21:08:25 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Coop Case Discussion QuestionsDocument3 pagesThe Coop Case Discussion QuestionsFernando Barbosa0% (1)

- Summary of Gary King, Robert O. Keohane & Sidney Verba's Designing Social InquiryFrom EverandSummary of Gary King, Robert O. Keohane & Sidney Verba's Designing Social InquiryNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Creep and Decision Accretion - CAROL H. WEISSDocument24 pagesKnowledge Creep and Decision Accretion - CAROL H. WEISSCindy ChiribogaNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal Checklist For Quantitative Descriptive Research v.1 1 3Document2 pagesCritical Appraisal Checklist For Quantitative Descriptive Research v.1 1 3Jusmine Rose MundaNo ratings yet

- Impulsive Decision Making and Choice BlindnessDocument3 pagesImpulsive Decision Making and Choice BlindnessAndraDediuNo ratings yet

- Child and Family Assessment in Social WorkDocument183 pagesChild and Family Assessment in Social WorkGeana100% (2)

- Reconsidering The Measurement of Political Knowledge: AcknowledgmentsDocument44 pagesReconsidering The Measurement of Political Knowledge: AcknowledgmentsAnne AlcudiaNo ratings yet

- (Arthur Lupia & Markus Prior) What Citizens Know Depends On How You Ask Them - Political Knowledge and Political Learning SkillsDocument43 pages(Arthur Lupia & Markus Prior) What Citizens Know Depends On How You Ask Them - Political Knowledge and Political Learning SkillsANTENOR JOSE ESCUDERO GÓMEZNo ratings yet

- Survey Research Method JournalDocument49 pagesSurvey Research Method JournalscorpioboyNo ratings yet

- Entrevista CognitivDocument25 pagesEntrevista CognitivCaroline PortoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877042815025884 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S1877042815025884 Mainzulqoidy habibieNo ratings yet

- Buchanan Kock InformationOverload 2001Document11 pagesBuchanan Kock InformationOverload 2001LoqmanHafizNo ratings yet

- University of The Cordilleras Department of Architecture: Ar 414 Research MethodDocument10 pagesUniversity of The Cordilleras Department of Architecture: Ar 414 Research MethoddeniseNo ratings yet

- Social Intelligence Research PapersDocument9 pagesSocial Intelligence Research Papersefhwx1vt100% (1)

- Senior Thesis MCB UiucDocument5 pagesSenior Thesis MCB UiucJoe Osborn100% (1)

- Kenett Surveys JAPS2006Document13 pagesKenett Surveys JAPS2006anaghamatriNo ratings yet

- Fitzgerald SkillsDocument20 pagesFitzgerald SkillsimgstackeNo ratings yet

- Raising Response Rates What WorksDocument17 pagesRaising Response Rates What WorksJasminah MalabiNo ratings yet

- Stages in Research ProcessDocument28 pagesStages in Research ProcessveralynnpNo ratings yet

- Lectura PrincipalDocument15 pagesLectura PrincipalJuani CaldeNo ratings yet

- Best Practices in The Collection of Conflict Data: Idean SalehyanDocument5 pagesBest Practices in The Collection of Conflict Data: Idean SalehyanBank Data FIA UNW MataramNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document6 pagesChapter 4MARIFA ROSERONo ratings yet

- Utilidad de Orientaciones PartidistasDocument25 pagesUtilidad de Orientaciones PartidistasManuel PellicerNo ratings yet