Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2991-Advanced Feline Medicine-Ferasin-How I Treat Congestive - Eng

2991-Advanced Feline Medicine-Ferasin-How I Treat Congestive - Eng

Uploaded by

Silvia RoseOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2991-Advanced Feline Medicine-Ferasin-How I Treat Congestive - Eng

2991-Advanced Feline Medicine-Ferasin-How I Treat Congestive - Eng

Uploaded by

Silvia RoseCopyright:

Available Formats

HOW I TREAT CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE IN CATS

Luca Ferasin

Specialist Veterinary Cardiology Consultancy Ltd

Cardiology

Four Marks, Hampshire

United Kingdom

INTRODUCTION

Despite substantial progress in diagnosis, classification and stratification of feline cardiac conditions,

there is still a substantial lack of evidence regarding efficacy of various therapies at different stages of

heart disease. Regrettably, randomized controlled clinical trials published so far do not seem to support

any particular therapeutic intervention, with the only exception of loop diuretics for the control of

cardiogenic pulmonary oedema.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT

Ideally, treatment of feline cardiomyopathy should be aimed at resolving all the underlying pathogenic

mechanisms of the disease, such as diastolic and systolic dysfunction, dynamic outflow obstruction,

ischaemia, arrhythmias, neuro-hormonal activation, and hyper-coagulability status. In reality, with the only

exception of taurine in cats with taurine-deficient DCM, such ideal treatment is not available and no drug

at present has convincingly demonstrated to improve survival and/or quality of life in cats with myocardial

disease.

The asymptomatic patient in Stage B1

Whether or not an asymptomatic cat with CM should be treated is a very controversial topic. Anecdotal

reports claim improvement of physical activity in asymptomatic cats with HCM treated with diltiazem or

beta-blockers. In addition, a recent pilot study has demonstrated a possible reduction of myocardial

damage in cats with compensated HCM following daily administration of atenolol, as suggested by a

significant reduction of circulating cTn-I. However, randomised placebo-controlled studies are still lacking

and clinical utility of diltiazem or beta-blockers in asymptomatic cats has still to be proven.

The use of ACE-inhibitors has also been advocated in cases of HCM, both in asymptomatic and

symptomatic cats. In that retrospective study, significant changes in cardiac dimensions where identified

echocardiographically together with an improvement of life expectancy after administration of enalapril.

Unfortunately, recent prospective, controlled study studies have failed to demonstrate significant effects

of ACE-inhibitor (benazepril and ramipril) in cats with sub-clinical forms of HCM.

The potassium sparing agent spironolactone has shown anti-remodelling properties in human patients

with asymptomatic cardiac disease, as well as in patients with mild CHF (NYHA class I and II). It might

be naïve, but it is not unrealistic, to believe that spironolactone may produce a similar effect in cats with

asymptomatic CM, although controlled clinical studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Regrettably, a study from Dr MacDonald (JVIM 2008; 22: 335–41) failed to demonstrate improvement of

diastolic function and LV mass in Maine Coon cats with HCM treated with spironolactone for 4 months.

Furthermore, in that study, one third of the treated cats developed severe ulcerative facial dermatitis.

However, to the best of the author’s knowledge, this side effect has rarely been reported in other breeds

or different clinical settings.

Cats with asymptomatic forms of CM but with echocardiographic evidence of intra-cavitary thrombi,

spontaneous echo-contrast or severe LA dilation may benefit from anti-thrombotic prophylaxis to reduce

the risk of ATE. This could theoretically be achieved by administering low-dose aspirin, clopidogrel or a

combination of the two drugs, although such combination has not shown clinical benefit in humans.

In summary, treatment of cats with subclinical CM remains controversial due to lack of evidence of benefit

at low or only minimal risk. While the majority of cats with stage B1 cardiomyopathy will never develop

clinical signs of their disease, it is advisable to monitor these cats annually for development of moderate

to severe LA enlargement (progression to stage B2). Cats with stage B1 cardiomyopathy are considered

at low risk of CHF or ATE, and in general treatment is not recommended.

The asymptomatic patient in Stage B2

Cats with stage B2 HCM have an increased risk of developing CHF and/or ATE. Prevention of ATE in

cats with subclinical cardiomyopathy has not been studied, but thromboprophylaxis might be considered

when known risk factors for ATE are present (moderate-severe LA enlargement, low LA FS%, low LA

appendage velocities, presence of spontaneous echo-contrast), as long as cat’s owners are made aware

of the lack of scientific evidence and that clopidogrel does not eliminate the risk of ATE in this feline

population (“duty to inform”). Cats in stage B2 should be monitored for progression of disease and

development of clinical signs, but the effects of stress caused by re-examination should also be taken

into consideration. If a stage B2 cat is re-examined, attention to appropriate handling and minimizing

detrimental stimuli is extremely important.

The symptomatic patient (cats in congestive heart failure; Stage C)

Cats presenting clinical or radiographic signs of CHF should be treated accordingly. In cases of acute

respiratory distress, stress should be minimised, and cage-rest and oxygen supplementation should be

instituted promptly. Pulmonary oedema is generally controlled by intravenous administration of

furosemide every 4-6 hours, until a normal respiratory rate is achieved. Dyspnoea secondary to pleural

effusion can be successfully managed by thoracocentesis. Sedative medication with acepromazine and

butorphanol may contribute to alleviate the respiratory distress. In extreme cases, where the patient does

not respond to acute diuresis, airway suctioning and mechanical ventilation can be considered. Once

pulmonary oedema is sufficiently controlled, furosemide can be given orally and at the lowest effective

dose. A similar approach should be taken in chronic and non-acute cases, in order to reduce the negative

side-effects of diuresis that can include reduced ventricular preload, hypotension, pre-renal azotaemia

and hypokalaemia, which can predispose to anorexia and severe ventricular arrhythmias. The risk of

hypokalaemia could be reduced by concomitant administration of potassium sparing agents, such as

spironolactone although sufficient data of its clinical efficacy in cats are not available.

In a recent pilot study (SEISICAT) spironolactone has shown to reduce the risk of an event occurrence in

the treatment group, while showing minimal side effects. Unfortunately, the SEISICAT study was affected

by a significant difference between treatment group and placebo group at entry. Therefore, more studies

are necessary to confirm the beneficial effects in the treatment of cats with congestive heart failure due to

CM.

Calcium channel blockers have been advocated as effective treatment for symptomatic feline HCM for

many years. Diltiazem has a lesser effect on the systemic vasculature and inotropic state than verapamil,

and it is generally the calcium channel blocker of choice in the treatment of feline HCM. The claimed

beneficial therapeutic effects of diltiazem are due to its positive lusitropic and coronary vasodilating

properties and include increased LV filling, reduced heart rate, increased venous oxygen tension,

improved echocardiographic parameters and resolved radiographic abnormalities. However, due to its

pharmacokinetics, diltiazem needs to be administered every 8 hours, and many clients struggle to comply

with this dosing frequency, administering the drug only once or twice daily. Unfortunately, the

administration of the extended release formulation is accompanied by significant side-effects.

Beta blockers have also been suggested as useful treatment of feline CM, since they can provide heart

rate and arrhythmia control, relieve LVOT obstruction and lessen myocardial oxygen demand. Atenolol, a

selective beta-1 agonist, is generally preferred over other beta-blockers (i.e. propranolol) because it

reduces the risk of bronchospasm. Furthermore it can be administered only once or twice daily versus the

recommended three times daily administrations of propranolol.

In 2003, a prospective double-blinded, multicentre, controlled study comparing the clinical efficacy of

atenolol, diltiazem and enalapril in cats with diastolic heart failure showed that cats receiving atenolol and

furosemide survived for a significantly shorter time than cats treated with furosemide alone. Similarly,

patients receiving diltiazem survived less than cats on furosemide alone, while cats in the enalapril group

did as well or better than the placebo group. However, these differences were not found to be statistically

significant. Therefore, a prudent approach should be taken when recommending any of these drugs, in

addition to furosemide, for chronic treatment of feline CM.

Taurine-deficient DCM cases, if confirmed, can be successfully treated with taurine supplementation, in

addition to supportive treatment to control the clinical signs of CHF, and echocardiographic evidence of

improved systolic function is generally seen within 6 weeks of supplementation.

Other cats with echocardiographic evidence of systolic dysfunction not related to taurine deficiency may

benefit from positive inotropic drugs. Dobutamine infusion can be considered in severe cases, especially

those accompanied by severe hypotension. Less severe cases may benefit from an oral positive inotropic

medication. Digoxin, for example, has been used for many years in cats but careful dosing and periodic

plasma measurements are necessary to reduce the risk of toxicity. Pimobendan can also be considered

in all cases of feline CM accompanied by systolic dysfunction. Although this drug is not licensed for use in

cats, its administration is well tolerated in this species, and induces significant improvement in the

demeanour and appetite of the treated cats in association with resolution of clinical signs. In addition to

its positive inotropic property, pimobendan has a positive lusitropic effect, which may also have benefits in

other forms of feline myocardial disease. However, further studies are necessary to confirm this

hypothesis.

Finally, whenever a primary cause of myocardial disease is suspected or recognised, every attempt

should be made to manage it directly. For example, sustained tachycardia can induce systolic dysfunction

(tachycardiomyopathy) but the myocardial lesions can be reversible if the arrhythmia is successfully

controlled. Similarly, corticosteroids may control the inflammatory changes in cases of myocarditis and,

where the cause is bacterial (e.g. Bartonella) or protozoal (e.g. Toxoplasma), antimicrobial treatment may

eliminate the aetiological agent.

REFERENCES

1. Ferasin L. Cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure. BSAVA Manual of Feline Practice: A

Foundation Manual. 1st Edition 2013. Wiley Ed.

2.. James R, Guillot E, Garelli-Paar C, Huxley J, Grassi V, Cobb M. The SEISICAT study: a pilot study

assessing efficacy and safety of spironolactone in cats with congestive heart failure secondary to

cardiomyopathy. J Vet Cardiol. 2018;20:1-12

3 Rishniw M, Pion PD. Is treatment of feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy based in science or faith? A

survey of cardiologists and a literature search. J Feline Med Surg. 2011;13:487-497

4 Luis Fuentes V, Abbott J, Chetboul V, Côté E, Fox PR, Häggström J, Kittleson MD, Schober K, Stern

JA. ACVIM consensus statement guidelines for the classification, diagnosis, and management of

cardiomyopathies in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:1062-1077

5. Ferasin L, DeFrancesco T. Management of acute heart failure in cats. J Vet Cardiol. 2015;17 Suppl

1:S173-89.

6 Schober KE, Rush JE, Luis Fuentes V, Glaus T, Summerfield NJ, Wright K, Lehmkuhl L, Wess G,

Sayer MP, Loureiro J, MacGregor J, Mohren N. Effects of pimobendan in cats with hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy and recent congestive heart failure: Results of a prospective, double-blind, randomized,

nonpivotal, exploratory field study. J Vet Intern Med. 2021;35:789-800

7 Schober KE, Zientek J, Li X, Fuentes VL, Bonagura JD. Effect of treatment with atenolol on 5-year

survival in cats with preclinical (asymptomatic) hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Vet Cardiol. 2013

Jun;15:93-104

8 King JN, Martin M, Chetboul V, Ferasin L, French AT, Strehlau G, Seewald W, Smith SGW, Swift ST,

Roberts SL, Harvey AM, Little CJL, Caney SMA, Simpson KE, Sparkes AH, Mardell EJ, Bomassi E,

Muller C, Sauvage JP, Diquélou A, Schneider MA, Brown LJ, Clarke DD, Rousselot JF. Evaluation of

benazepril in cats with heart disease in a prospective, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical

trial. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:2559-2571

You might also like

- AAFP Family Med Board QuestionsDocument96 pagesAAFP Family Med Board QuestionsKamil Hanna100% (2)

- HY Pearls From UWorld Step3 PDFDocument91 pagesHY Pearls From UWorld Step3 PDFJohn Smith100% (1)

- ECG Mastery Blue Belt Workbook PDFDocument135 pagesECG Mastery Blue Belt Workbook PDFPadma Priya Duvvuri100% (5)

- 2994-Advanced Medicine Cardiology-Ferasin-How I Treat Heart - EngDocument5 pages2994-Advanced Medicine Cardiology-Ferasin-How I Treat Heart - EngSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- Dilated Cardiomyopathy TherapyDocument7 pagesDilated Cardiomyopathy Therapyedrash85No ratings yet

- NullDocument11 pagesNullKareem SaeedNo ratings yet

- Felinecongestiveheart Failure: Current Diagnosis and ManagementDocument10 pagesFelinecongestiveheart Failure: Current Diagnosis and ManagementJuan Fernando Herrera CiroNo ratings yet

- Obat Yang Bekerja Pada Sistem KardiovaskulerDocument18 pagesObat Yang Bekerja Pada Sistem KardiovaskulerMuhammad IkbalNo ratings yet

- Flashcards - QuizletDocument7 pagesFlashcards - QuizletNEsreNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy of Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)Document163 pagesPharmacotherapy of Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)Aditya rathoreNo ratings yet

- High Yield Board ReviewDocument5 pagesHigh Yield Board ReviewMarcoNo ratings yet

- Prehospital Care: Immediate Interventions - AbcsDocument8 pagesPrehospital Care: Immediate Interventions - AbcsindahkurNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Emergencies: BY: Dr. Imtiyaz Hashim (PGR) Dr. Khalida Baloch (Ho)Document31 pagesHypertensive Emergencies: BY: Dr. Imtiyaz Hashim (PGR) Dr. Khalida Baloch (Ho)امتیاز ہاشم بزنجوNo ratings yet

- Congestive Cardiac FailureDocument24 pagesCongestive Cardiac FailureFarheen KhanNo ratings yet

- Captopril Attenuates Cardiovascular and Renal Disease in A Rat Model of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection FractionDocument10 pagesCaptopril Attenuates Cardiovascular and Renal Disease in A Rat Model of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection FractionLam Sin YiNo ratings yet

- Drug Study ArvinDocument6 pagesDrug Study ArvinArvin BeltranNo ratings yet

- ThromboembolismDocument1 pageThromboembolismMaria YanezNo ratings yet

- Stopp Start ToolkitDocument22 pagesStopp Start ToolkitRifky IlhamiNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument6 pagesUntitled DocumentCharlyn JenselNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Dysrhythmia Case StudyDocument6 pagesCardiac Dysrhythmia Case StudyCharlyn JenselNo ratings yet

- CC Junsay Nicole Xyza T. Learning Interaction FormDocument10 pagesCC Junsay Nicole Xyza T. Learning Interaction FormNicole Xyza JunsayNo ratings yet

- Hypertension in Special Population.Document25 pagesHypertension in Special Population.Anamta AshfaqNo ratings yet

- Constrictive Pericarditis: There Are Some Disease As A DifferentialDocument3 pagesConstrictive Pericarditis: There Are Some Disease As A DifferentialPradnya ParamitaNo ratings yet

- CardiologyDocument9 pagesCardiologyAbi RajasingamNo ratings yet

- Cardio-Cerebrovascular Pharmacotherapy: Sutomo Tanzil Dept - of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Sriwijaya UniversityDocument32 pagesCardio-Cerebrovascular Pharmacotherapy: Sutomo Tanzil Dept - of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Sriwijaya UniversityFarahEzzlynnNo ratings yet

- Cardio Lab MedsDocument11 pagesCardio Lab MedsDianne Erika MeguinesNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy: Sutomo Tanzil Dept - of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Sriwijaya UniversityDocument44 pagesCardiovascular Pharmacotherapy: Sutomo Tanzil Dept - of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Sriwijaya UniversitydeviamufidazaharaNo ratings yet

- B BlockersDocument11 pagesB BlockersIRINANo ratings yet

- DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure SBP: Systolic Blood PressureDocument7 pagesDBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure SBP: Systolic Blood PressureM. JoyceNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in Congestive Heart FailureDocument47 pagesRecent Advances in Congestive Heart FailurePrateek KanadeNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure: Andi Putriani 10542 0203 10 Dr. Ratni Rahim, Sp. PDDocument12 pagesHeart Failure: Andi Putriani 10542 0203 10 Dr. Ratni Rahim, Sp. PDPrincess LoveyChanNo ratings yet

- CaballeroDocument4 pagesCaballeroClairyssa Myn D CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Case 1 & 2Document4 pagesCase 1 & 2Adeel ShahidNo ratings yet

- Nuove Prospettive Nel Trattamento Dello Scompenso Acuto: Congresso Regionale ANMCO Toscana, Viareggio, 7 OTTOBRE 2011Document35 pagesNuove Prospettive Nel Trattamento Dello Scompenso Acuto: Congresso Regionale ANMCO Toscana, Viareggio, 7 OTTOBRE 2011Billy SNo ratings yet

- Heart FailureDocument6 pagesHeart FailureNatasha MarksNo ratings yet

- CardiologyDocument20 pagesCardiologycnnc21No ratings yet

- Icc UltimoDocument18 pagesIcc UltimoJoshua Alberto Gracia MancillaNo ratings yet

- Cardiovet OdtDocument26 pagesCardiovet OdtTiberiu CttNo ratings yet

- A Drug Study On EpinephrineDocument7 pagesA Drug Study On EpinephrineMaesy Garcia LorenaNo ratings yet

- Falla CardiacaDocument6 pagesFalla CardiacaFelipeNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Congestive Heart FailureDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Congestive Heart Failureefdwvgt4100% (1)

- TMJ - Fluid Management in Heart FailureDocument5 pagesTMJ - Fluid Management in Heart FailureSamir SarkarNo ratings yet

- ACE Inhibitors & Angiotensin II Antagonists: October 1997Document4 pagesACE Inhibitors & Angiotensin II Antagonists: October 1997indee533No ratings yet

- ICCI PatofisiologíaDocument10 pagesICCI PatofisiologíaAndrea Roman chavezNo ratings yet

- End-Stage Heart DiseaseDocument44 pagesEnd-Stage Heart DiseaseCyrille AgnesNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pearls CardiologyDocument6 pagesClinical Pearls CardiologyMaritza24No ratings yet

- Management of The Geriatric Psittacine Patient (2012)Document9 pagesManagement of The Geriatric Psittacine Patient (2012)Veronica Hdez FloresNo ratings yet

- Question 1 of 10: AAFP Board Review Clinchers Cardio Quiz 1Document60 pagesQuestion 1 of 10: AAFP Board Review Clinchers Cardio Quiz 1pramesh1No ratings yet

- ModMed CardiologyDocument77 pagesModMed CardiologyLee Tzong YewNo ratings yet

- HypertensionDocument10 pagesHypertensionaa zzNo ratings yet

- Drugs Acting On Respiratory System of AnimalsDocument8 pagesDrugs Acting On Respiratory System of AnimalsSunil100% (4)

- Amlodipine BesylateDocument7 pagesAmlodipine BesylatebabuagoodboyNo ratings yet

- Blood Pressure: A Critical Factor: KeypointsDocument6 pagesBlood Pressure: A Critical Factor: KeypointsWilmer RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Bacaan Autonomic DysreflexiaDocument5 pagesBacaan Autonomic DysreflexiaPatriationkNo ratings yet

- IRIS 2009 Treatment Recommendations SummaryDocument5 pagesIRIS 2009 Treatment Recommendations SummaryJessicaHernandezNo ratings yet

- AAFP NotesDocument3 pagesAAFP Notesadmitone01No ratings yet

- CHF LastDocument52 pagesCHF LastAli YousefNo ratings yet

- Pharm Final ReviewDocument8 pagesPharm Final ReviewKasey C. PintoNo ratings yet

- NCM 106 Learning Activities (Semis)Document12 pagesNCM 106 Learning Activities (Semis)Kimberly Abellar LatoNo ratings yet

- 2971-Advanced Surgery-Tivers-Congenital Portosystem - EngDocument4 pages2971-Advanced Surgery-Tivers-Congenital Portosystem - EngSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- 2998-Behaviour-Gonzalez Martinez-Hyperactive Dogs - EngDocument3 pages2998-Behaviour-Gonzalez Martinez-Hyperactive Dogs - EngSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- RJ Protocol CAD50Document2 pagesRJ Protocol CAD50Silvia RoseNo ratings yet

- Target Cat (Side One AMO20) PRDocument1 pageTarget Cat (Side One AMO20) PRSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- Ease The Pressure Campaign NEW CPDDocument2 pagesEase The Pressure Campaign NEW CPDSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- VetSurg - 2021 Whitney - Ex Vivo Biomechanical Comparison of Four Center of Rotation Angulation Based LevelingDocument6 pagesVetSurg - 2021 Whitney - Ex Vivo Biomechanical Comparison of Four Center of Rotation Angulation Based LevelingSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- BOAS Surgery Guide - February 2024 Issue 1 DIGITALDocument15 pagesBOAS Surgery Guide - February 2024 Issue 1 DIGITALSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- Pyogenic Brain Abscess A 15 Year SurveryDocument10 pagesPyogenic Brain Abscess A 15 Year SurverySilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- VetSurg - 2007 TOMLINSON - Measurement of Femoral Angles in Four Dog BreedsDocument6 pagesVetSurg - 2007 TOMLINSON - Measurement of Femoral Angles in Four Dog BreedsSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- VetSurg - 2001 Kaiser - MRI Measurements of The Q Angle in Dogs With Congenital MPLDocument7 pagesVetSurg - 2001 Kaiser - MRI Measurements of The Q Angle in Dogs With Congenital MPLSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- VetSurg - 2022 Peycke - Center of Rotation of Angulation-Based Leveling Osteotomy For Stifle Stabilization inDocument8 pagesVetSurg - 2022 Peycke - Center of Rotation of Angulation-Based Leveling Osteotomy For Stifle Stabilization inSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Surgery - 2019 - Easter - Accuracy of Three-Dimensional Printed Patient-Specific Drill Guides For Treatment of HIFDocument10 pagesVeterinary Surgery - 2019 - Easter - Accuracy of Three-Dimensional Printed Patient-Specific Drill Guides For Treatment of HIFSilvia RoseNo ratings yet

- The Biochemical Panel: Is The Diagnosis Hiding in Plain Site?Document47 pagesThe Biochemical Panel: Is The Diagnosis Hiding in Plain Site?Silvia RoseNo ratings yet

- Resumen Unidad 2Document31 pagesResumen Unidad 2yeseniaram073No ratings yet

- All Past Rounds Cardio MCQs AlexandriaDocument37 pagesAll Past Rounds Cardio MCQs AlexandriaMahmoud Abouelsoud100% (1)

- Chronic Congestive Heart FailureDocument10 pagesChronic Congestive Heart FailureEllappa GhanthanNo ratings yet

- Gyanodaya Sr. Sec. School Khurai: Art Investigatory ProjectDocument45 pagesGyanodaya Sr. Sec. School Khurai: Art Investigatory ProjectMahendra KushwahaNo ratings yet

- Resume CV Houston Based Physician Assistant Cardiology and ER Experience Seeking New Opportunities in Houston Texas Area Post Medical Resume Physician CVDocument2 pagesResume CV Houston Based Physician Assistant Cardiology and ER Experience Seeking New Opportunities in Houston Texas Area Post Medical Resume Physician CVRick WhitleyNo ratings yet

- REVISI 1st Announcement Book 27th ASMIHA 2018 - 12des2017Document21 pagesREVISI 1st Announcement Book 27th ASMIHA 2018 - 12des2017Jimmy Oi SantosoNo ratings yet

- Anticoagulants Preoperative InstructionsDocument3 pagesAnticoagulants Preoperative InstructionsDevaki VisvalingamNo ratings yet

- Ramadan Timings and Clinic Allocation PDFDocument8 pagesRamadan Timings and Clinic Allocation PDFzahidNo ratings yet

- Lecturio Pericardial Effusion & Cardiac TamponadeDocument1 pageLecturio Pericardial Effusion & Cardiac TamponadeCecil-An DalanonNo ratings yet

- Olewinski 2016Document15 pagesOlewinski 2016Nazihan Safitri AlkatiriNo ratings yet

- Circulationaha 108 191098Document9 pagesCirculationaha 108 191098rajesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Lucknow Hospital OPD Schedule1Document2 pagesLucknow Hospital OPD Schedule1Romesh KumarNo ratings yet

- AHA Elearning - ACLS Precourse Self-Assessment and Precourse WorkDocument3 pagesAHA Elearning - ACLS Precourse Self-Assessment and Precourse WorkMalik AljaberiNo ratings yet

- Antiarrhythmic DrugsDocument21 pagesAntiarrhythmic DrugsShoeb Nawaz Khan100% (1)

- List of Hospitals Gujarat PDFDocument11 pagesList of Hospitals Gujarat PDFVijay ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Valvular Heart DiseaseDocument6 pagesValvular Heart DiseaseShafiq ZahariNo ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary Practice PatternsDocument909 pagesCardiopulmonary Practice PatternsDuncan D'Amico0% (1)

- Hemodynamic Unstable Patient Following ArrhythmiaDocument30 pagesHemodynamic Unstable Patient Following Arrhythmialew chin hongNo ratings yet

- Vivid 2Document5 pagesVivid 2Iqra ChuhanNo ratings yet

- Bonin Et Al-2018-Catheterization and Cardiovascular InterventionsDocument6 pagesBonin Et Al-2018-Catheterization and Cardiovascular InterventionsPhan AnNo ratings yet

- Diet Plan PDFDocument9 pagesDiet Plan PDFComet ShopNo ratings yet

- ACLSDocument26 pagesACLSrobmadereNo ratings yet

- Sindromul Coronarian Acut: UMF VB Timisoara Departamentul VI Medicina Interna de AmbulatorDocument78 pagesSindromul Coronarian Acut: UMF VB Timisoara Departamentul VI Medicina Interna de AmbulatorIulia CeveiNo ratings yet

- Left-Sided Heart Failure - Symptoms, Causes and TreatmentDocument14 pagesLeft-Sided Heart Failure - Symptoms, Causes and TreatmentHanzala Safdar AliNo ratings yet

- Sekilas InfoDocument15 pagesSekilas InfoZukmianty SuaibNo ratings yet

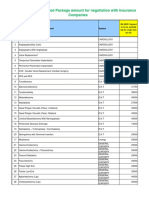

- IMA NHB Suggested Package Amount For Negotiation With Insurance CompaniesDocument5 pagesIMA NHB Suggested Package Amount For Negotiation With Insurance Companiesmonikparmar1No ratings yet

- DR Surya DarmaDocument44 pagesDR Surya Darmadpk ppnirsinuNo ratings yet

- AnestesiaDocument18 pagesAnestesiaGündüz AğayevNo ratings yet

- 01 Pediatrics in Review - January2010Document69 pages01 Pediatrics in Review - January2010Madhaw BajajNo ratings yet