Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hemolytic Reaction in The Washed Salvaged Blood of

Hemolytic Reaction in The Washed Salvaged Blood of

Uploaded by

Tandyo TriasmoroCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Slide Kuliah Transfusi DarahDocument31 pagesSlide Kuliah Transfusi Darahfenti nurul khafifahNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Lessons From Derivatives MishapsDocument3 pagesAssignment 3 Lessons From Derivatives MishapsSandip Chovatiya100% (2)

- KAR Products - Hi Temp Industrial Anti-SeizeDocument6 pagesKAR Products - Hi Temp Industrial Anti-Seizejaredf@jfelectric.comNo ratings yet

- Firm AnalysisDocument7 pagesFirm Analysisapi-518500123100% (1)

- Acute Oxaliplatin-Induced Hemolytic Anemia, Thrombocytopenia, and Renal Failure: Case Report and A Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesAcute Oxaliplatin-Induced Hemolytic Anemia, Thrombocytopenia, and Renal Failure: Case Report and A Literature ReviewNurul Kamilah SadliNo ratings yet

- 7: Effective Transfusion in Surgery and Critical CareDocument16 pages7: Effective Transfusion in Surgery and Critical CareNick-Hugh Sean WisdomNo ratings yet

- SLED Vs CRRT PDFDocument9 pagesSLED Vs CRRT PDFquilino2012No ratings yet

- Influence of Dry Weight Reduction On Anemia in Patients Undergoing HemodialysisDocument12 pagesInfluence of Dry Weight Reduction On Anemia in Patients Undergoing HemodialysisFajar JarrNo ratings yet

- 2015 Haemostatic Management of Cardiac Surgical HaemorrhageDocument12 pages2015 Haemostatic Management of Cardiac Surgical HaemorrhageDidier AdodoNo ratings yet

- 10 1097MD 0000000000000587Document3 pages10 1097MD 0000000000000587abbasamiri135103No ratings yet

- Niknam 2019Document8 pagesNiknam 2019Valdir ReisNo ratings yet

- Transfusion Guidelines HemDocument4 pagesTransfusion Guidelines HemnandhinisankaranNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument10 pagesResearch ArticleAnonymous SbnDyANo ratings yet

- Blood Conservation in Pediatric Cardiac SurgeryDocument5 pagesBlood Conservation in Pediatric Cardiac Surgerymohanakrishna007No ratings yet

- Effects of Cardiopulmonary Bypass On Mediastinal Drainage and The Use of Blood Products in The Intensive Care Unit in 60-To 80-Year-Old Patients Who Have Undergone Coronary Artery Bypass GraftingDocument8 pagesEffects of Cardiopulmonary Bypass On Mediastinal Drainage and The Use of Blood Products in The Intensive Care Unit in 60-To 80-Year-Old Patients Who Have Undergone Coronary Artery Bypass GraftingYogi TrilaksonoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument11 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- A. 24 Hours Pre-Operatively B. 2 Hours Pre-Operatively C. Whilst Making The Skin IncisionDocument75 pagesA. 24 Hours Pre-Operatively B. 2 Hours Pre-Operatively C. Whilst Making The Skin Incision5alifa55No ratings yet

- Aliment Pharmacol Ther - 2022 - Tergast - Home Based Tunnelled Peritoneal Drainage System As An Alternative TreatmentDocument11 pagesAliment Pharmacol Ther - 2022 - Tergast - Home Based Tunnelled Peritoneal Drainage System As An Alternative TreatmentTens AiepNo ratings yet

- Refractory Septic ShockDocument5 pagesRefractory Septic ShockBrian Antonio Veramatos LopezNo ratings yet

- Rituximab (Mabthera) SD Antifosfolipidos 4Document7 pagesRituximab (Mabthera) SD Antifosfolipidos 4AlexNo ratings yet

- BR J Haematol - 2009 - DIC MXDocument10 pagesBR J Haematol - 2009 - DIC MXAdil EissaNo ratings yet

- Critical Care 123Document66 pagesCritical Care 123Mr.ShazNo ratings yet

- Briggs2006 PDFDocument10 pagesBriggs2006 PDFRonal WinterNo ratings yet

- Hypervolemia Increases Release of Atrial Natriuretic Peptide and Shedding of The Endothelial GlycocalyxDocument8 pagesHypervolemia Increases Release of Atrial Natriuretic Peptide and Shedding of The Endothelial GlycocalyxbayanganNo ratings yet

- Small Volume Resuscitation With 20 Albumin in Intensive Care Physiological EffectsDocument10 pagesSmall Volume Resuscitation With 20 Albumin in Intensive Care Physiological EffectsDr. Prashant KumarNo ratings yet

- Massive Transfusion - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument6 pagesMassive Transfusion - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfsadam sodomNo ratings yet

- TRF 14043Document10 pagesTRF 14043Ahmad ANo ratings yet

- BloodDocument7 pagesBloodWael AlmahdiNo ratings yet

- PIIS0007091222006201Document10 pagesPIIS0007091222006201Xavi Navarro FontNo ratings yet

- Evidencia Transfusion HemoderivadosDocument13 pagesEvidencia Transfusion HemoderivadosHernando CastrillónNo ratings yet

- TMP 9 B42Document6 pagesTMP 9 B42FrontiersNo ratings yet

- NIGAMDocument5 pagesNIGAMameenNo ratings yet

- Impact of Albumin RL For BTDocument10 pagesImpact of Albumin RL For BTSandeep BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- TransfusiDocument9 pagesTransfusiabbhyasa5206No ratings yet

- Vasoplegic SyndromeDocument41 pagesVasoplegic SyndromeFaizan Ahmad Ali100% (1)

- Guidline Penanganan Aplastic Anemia PDFDocument28 pagesGuidline Penanganan Aplastic Anemia PDFkeyla_shineeeNo ratings yet

- Washed Red Cells: Theory and Practice: Review ArticleDocument11 pagesWashed Red Cells: Theory and Practice: Review Articlemy accountNo ratings yet

- Management of A Kaposiform Haemangioendothelioma of T - 2016 - Pediatric HematolDocument4 pagesManagement of A Kaposiform Haemangioendothelioma of T - 2016 - Pediatric HematolHawin NurdianaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Red Cell Rejuvenation Versus Mechanical Washing For The Prevention of Transfusion-Associated Organ Injury in SwineDocument11 pagesA Comparison of Red Cell Rejuvenation Versus Mechanical Washing For The Prevention of Transfusion-Associated Organ Injury in Swinealfrilia0843No ratings yet

- Preoptimisation of Haemoglobin: General Anaesthesia Tutorial 389Document5 pagesPreoptimisation of Haemoglobin: General Anaesthesia Tutorial 389bobbykrishNo ratings yet

- Blood ProductsDocument41 pagesBlood ProductsrijjorajooNo ratings yet

- An International Consensus Statement On The Management of Postoperative Anaemia After Major Surgical ProceduresDocument14 pagesAn International Consensus Statement On The Management of Postoperative Anaemia After Major Surgical ProceduresEdwin PradanaNo ratings yet

- Intermittent Hemodialysis For Managing Metabolic Acidosis During Resuscitation of Septic Shock: A Descriptive StudyDocument5 pagesIntermittent Hemodialysis For Managing Metabolic Acidosis During Resuscitation of Septic Shock: A Descriptive Studyilham masdarNo ratings yet

- PEG-conjugated Hemoglobin Combination With Cisplatin Enforced The Antiangiogeic Effect in A Cervical Tumor Xenograft ModelDocument12 pagesPEG-conjugated Hemoglobin Combination With Cisplatin Enforced The Antiangiogeic Effect in A Cervical Tumor Xenograft ModelIstván PortörőNo ratings yet

- Canine Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia Treatment and PrognosisDocument10 pagesCanine Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia Treatment and PrognosisDiana LoayzaNo ratings yet

- Blood and Blood Product (F)Document50 pagesBlood and Blood Product (F)bharat singhNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionsDocument52 pagesBlood TransfusionsZuhri RomiNo ratings yet

- Dgac 201Document8 pagesDgac 201Reinaldi octaNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia - 2018 - Mu OzDocument14 pagesAnaesthesia - 2018 - Mu OzCarp TheodorNo ratings yet

- MJCU_Volume 88_Issue December_Pages 2121-2129Document9 pagesMJCU_Volume 88_Issue December_Pages 2121-2129jihansalma00No ratings yet

- MainDocument8 pagesMainAdityaRestuRahayuNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass A SystematicDocument21 pagesAnesthetic Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass A SystematicFabio MeloNo ratings yet

- Extracorporeal Photopheresis in Pediatric Patients Practical and Technical ConsiderationsDocument10 pagesExtracorporeal Photopheresis in Pediatric Patients Practical and Technical Considerationselenaa.hp28No ratings yet

- Case Study Residency2Document21 pagesCase Study Residency2computerwhiz42985No ratings yet

- DrHSMurthy HiPECDocument11 pagesDrHSMurthy HiPECReddyNo ratings yet

- 14 - Mazandarani2012Document7 pages14 - Mazandarani2012TandeanTommyNovenantoNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Spontaneous Hepatic Rupture in A Pregnant WomanDocument4 pagesA Rare Case of Spontaneous Hepatic Rupture in A Pregnant WomanFatmawati MahirNo ratings yet

- 1 Transfusion1 PDFDocument7 pages1 Transfusion1 PDFVatha NaNo ratings yet

- Posttransfusion Refractory ThrombocytopeniaDocument19 pagesPosttransfusion Refractory ThrombocytopeniaKyla ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Aliment Pharmacol Ther - 2012 - Restellini - Red Blood Cell Transfusion Is Associated With Increased Rebleeding in Patients PDFDocument7 pagesAliment Pharmacol Ther - 2012 - Restellini - Red Blood Cell Transfusion Is Associated With Increased Rebleeding in Patients PDFzevillaNo ratings yet

- Blood Product Replacement For Postpartum HemorrhageDocument7 pagesBlood Product Replacement For Postpartum HemorrhageAlberto LiraNo ratings yet

- Standard Renal Replacement Therapy Combined With HemoadsorptionDocument8 pagesStandard Renal Replacement Therapy Combined With HemoadsorptionMihai PopescuNo ratings yet

- Article Hysteroscopic Tubal PatencyDocument7 pagesArticle Hysteroscopic Tubal PatencyTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Physiological Control of Mammary Growth, Lactogenesis, and Lactation 1Document19 pagesPhysiological Control of Mammary Growth, Lactogenesis, and Lactation 1Tandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Society For Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #49: Cesarean Scar PregnancyDocument13 pagesSociety For Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #49: Cesarean Scar PregnancyTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Induction of Lactation: Estrogen and Progesterone in Milk IDocument7 pagesHormonal Induction of Lactation: Estrogen and Progesterone in Milk ITandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Uog 20150Document9 pagesUog 20150Tandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Post Ligation Syndrome / Menstrual Disorders After Tubal LigationDocument4 pagesPost Ligation Syndrome / Menstrual Disorders After Tubal LigationTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Pitfalls in The Assessment of Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisDocument7 pagesPitfalls in The Assessment of Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Kinomoto Kondo2016Document7 pagesKinomoto Kondo2016Tandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Correspondence: Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisDocument1 pageCorrespondence: Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- About Gazi Auto BrickDocument19 pagesAbout Gazi Auto BrickMd. Reza-Ul- HabibNo ratings yet

- Poulos Bill - The Truth About Fibonacci TradingDocument23 pagesPoulos Bill - The Truth About Fibonacci TradingPantera1010No ratings yet

- Report On Financial Analysis of Textile Industry of BangladeshDocument39 pagesReport On Financial Analysis of Textile Industry of BangladeshSaidur0% (2)

- Basic PEAT ManualDocument14 pagesBasic PEAT Manualvanderwalt.paul2286100% (1)

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument142 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentMark Nel VenusNo ratings yet

- 2 Education FCE SpeakingDocument3 pages2 Education FCE SpeakingMaryna TsehelskaNo ratings yet

- 5 Min FlipDocument76 pages5 Min FlipAnonymous JrCVpuNo ratings yet

- Pro Material Series: Free Placement Video Tutorial With Mock Test VisitDocument10 pagesPro Material Series: Free Placement Video Tutorial With Mock Test VisitPuneethNo ratings yet

- Jose Rizal's Life, Works and Studies in Europe (Part 1)Document5 pagesJose Rizal's Life, Works and Studies in Europe (Part 1)Russen Belen50% (2)

- pCO Electronic Control Chillers Aries Free-CoolingDocument94 pagespCO Electronic Control Chillers Aries Free-CoolingStefania FerrarioNo ratings yet

- Personality and Cultural Values PresentationDocument17 pagesPersonality and Cultural Values PresentationTaimoor AbidNo ratings yet

- HR Om11 ch05Document80 pagesHR Om11 ch05FADHIA AULYA NOVIANTYNo ratings yet

- Brochure Bananas PDFDocument2 pagesBrochure Bananas PDFPorcoddioNo ratings yet

- 3 - SR - Q1 2022 Chicken Egg Situation Report - v2 - ONS-signedDocument6 pages3 - SR - Q1 2022 Chicken Egg Situation Report - v2 - ONS-signedMonette De CastroNo ratings yet

- Science Technology and Society MODULE 3Document7 pagesScience Technology and Society MODULE 3jesson cabelloNo ratings yet

- Greaves Cotton: Upgraded To Buy With A PT of Rs160Document3 pagesGreaves Cotton: Upgraded To Buy With A PT of Rs160ajd.nanthakumarNo ratings yet

- Module 1 STSDocument22 pagesModule 1 STSGinaly Pico100% (1)

- !insanity CalendarDocument5 pages!insanity CalendarOctavio BejaranoNo ratings yet

- Grace Varas, DO UT Health Division of Geriatric & Palliative Medicine, Department of Internal MedicineDocument27 pagesGrace Varas, DO UT Health Division of Geriatric & Palliative Medicine, Department of Internal MedicinePriyesh CheralathNo ratings yet

- Plate Tectonics VocabularyDocument4 pagesPlate Tectonics VocabularyJamela PalomoNo ratings yet

- FarnchiseeDocument31 pagesFarnchiseeSk DadarNo ratings yet

- Convertible Note Agreement - SkillDzireDocument16 pagesConvertible Note Agreement - SkillDzireMAツVIcKYツNo ratings yet

- Shani Sadhe Sati and DhaiyaDocument2 pagesShani Sadhe Sati and DhaiyaSanjay DhimanNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning For EveryoneDocument3 pagesMachine Learning For Everyonejppn33No ratings yet

- Palayan CDP Final PpdoDocument109 pagesPalayan CDP Final PpdoMargarita AngelesNo ratings yet

- Sharjaa CarbonatesDocument190 pagesSharjaa CarbonatesRuben PradaNo ratings yet

- There Ain't No Cure For Love: The Psychotherapy of An Erotic TransferenceDocument7 pagesThere Ain't No Cure For Love: The Psychotherapy of An Erotic TransferenceВасилий МанзарNo ratings yet

Hemolytic Reaction in The Washed Salvaged Blood of

Hemolytic Reaction in The Washed Salvaged Blood of

Uploaded by

Tandyo TriasmoroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hemolytic Reaction in The Washed Salvaged Blood of

Hemolytic Reaction in The Washed Salvaged Blood of

Uploaded by

Tandyo TriasmoroCopyright:

Available Formats

Kawamoto et al.

BMC Anesthesiology (2019) 19:83

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-019-0752-4

CASE REPORT Open Access

Hemolytic reaction in the washed salvaged

blood of a patient with paroxysmal

nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Yuko Kawamoto1, Tasuku Nishihara1* , Aisa Watanabe1, Kazuo Nakanishi2, Taisuke Hamada1, Amane Konishi1,

Naoki Abe1, Sakiko Kitamura1, Keizo Ikemune1, Yuichiro Toda3 and Toshihiro Yorozuya1

Abstract

Background: In patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH), the membrane-attack complex (MAC)

formed on red blood cells (RBCs) causes hemolysis due to the patient’s own activated complement system by an

infection, inflammation, or surgical stress. The efficacy of transfusion therapy for patients with PNH has been documented,

but no studies have focused on the perioperative use of salvaged autologous blood in patients with PNH.

Case presentation: A 71-year-old man underwent total hip replacement surgery. An autologous blood salvage device

was put in place due to the large bleeding volume and the existence of an irregular antibody. The potassium

concentration in the transfer bag of salvaged RBCs after the wash process was high at 6.2 mmol/L, although the

washing generally removes > 90% of the potassium from the blood. This may have been caused by continued

hemolysis even after the wash process. Once activated, the complement in patients with PNH forms the MAC on

the RBCs, and the hemolytic reaction may not be stopped even with RBC washing.

Conclusions: Packed RBCs, instead of salvaged autologous RBCs, should be used for transfusions in patients with

PNH. The use of salvaged autologous RBCs in patients with PNH should be limited to critical situations, such as

massive bleeding. Physicians should note that the hemolytic reaction may be present inside the transfer bag

even after the wash process.

Keywords: Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, Blood salvage device, Autologous blood transfusion, Complement,

Hemolysis, Hyperkalemia, Potassium

Background are deficient. Therefore, red blood cells (RBCs) are

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH; OMIM destroyed by the membrane-attack complex (MAC)

300818) is a rare disease, which is caused by a mutation formed by the body’s own activated complement system.

in the PIGA gene on chromosome Xp22 [1]. Rare The use of transfusion therapy for patients with PNH

Disease Database of National Organization for Rare has been well studied. Washed RBCs lacking white blood

Disorders reports that the estimated prevalence is 0.5– cells and complement components were used in the

1.5 per million people in the general population. The past, but the practice of washing the RBCs was deemed

mutation in the PIGA gene causes the deficit or lack of unnecessary and packed RBCs are usable without any

glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins, problem for patients with PNH [2]. However, no reports

and as a result, GPI-anchored type factors regulating the have focused on the use of perioperative salvaged autolo-

complement system on the membrane of red blood cell gous RBCs for patients with PNH. In here, we describe a

[CD55 or decay-accelerating factor (DAF) and CD59] case involving the use of salvaged autologous RBCs in a

patient with PNH.

* Correspondence: ntasukuk@yahoo.co.jp

1

Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Ehime University

Graduate School of Medicine, Shitsukawa, Toon, Ehime 791-0295, Japan

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Kawamoto et al. BMC Anesthesiology (2019) 19:83 Page 2 of 4

Case presentation The amount of bleeding during the operation was 1900 ml,

A 71-year-old man was scheduled to undergo total hip and the infusion volume during the operation was 2400 ml

replacement surgery under general anesthesia to fix of crystalloids, 6 units of packed RBCs, and 280 ml of

malunion of the right hip joint. Two months before the salvaged autologous RBCs. The duration of surgery and

scheduled procedure, he had undergone left bipolar hip anesthesia was 140 and 215 min, respectively. Postopera-

arthroplasty and right acetabular fracture fixation due to tively, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit

bilateral acetabular cartridge fractures. After the frac- (ICU).

tures, the patient had been prescribed oral polystyrene

sulfonate calcium because of hyperkalemia. He was diag- Postoperative course

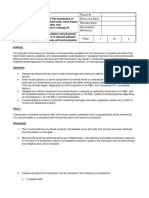

nosed to have PNH at the age of 60, and the oral admin- Figure 1b indicates the patient’s progress after the oper-

istration of prednisolone was initiated. The therapy with ation. Glucose-insulin therapy was continued until the

eculizumab was not initiated. postoperative day (POD) 1. The patient left the ICU and

restarted the oral intake of polystyrene sulfonate calcium at

Preoperative examination POD 3 because the K+ increased again. At POD 18, the pa-

The preoperative blood examination showed pancyto- tient was transferred to another hospital for rehabilitation.

penia [white blood cells, 2.100/μl; hemoglobin (Hb),

12.7 g/dl; and platelets, 100 × 103/μl]. We suspected a Discussion and conclusion

hemolytic reaction due to the presence of a slightly in- In normal blood, hemolytic reactions do not occur in

creased aspartate aminotransferase, although bilirubin the absence of antigen-antibody reactions, but the

and lactase dehydrogenase level were within the normal hemolytic reactions in patients with PNH are independ-

limits. The hyperkalemia improved with the polystyrene ent of antigen-antibody reactions. In patients with PNH,

sulfonate calcium. The irregular antibody screening was RBCs are destroyed by an activated complement system

positive. Therefore, 6 units of packed RBCs and a blood due to the deficit of membrane proteins DAF and CD59,

salvage device (electa™; Sorin Group Italia, Italy) were which inhibit the formation of the MAC.

prepared. No other abnormal results in the cardiac, liver, Transfusions in patients with PNH used to be per-

or renal functions were observed. formed with saline washed RBCs to reduce the risk of

leukocyte sensitization, antibody production against

Intraoperative findings human leukocyte antigens, and reactions which may

Figure 1a depicts the intraoperative progress course. The activate complement system [3]. However, a review on

Hb and potassium (K+) levels after the anesthesia induction the subject concluded that the use of washed RBCs is

were 11.5 g/dL and 4.6 mmol/L, respectively. An hour after not necessary and group-specific fresh blood and blood

the operation started, the same levels became 9.6 g/dL and products should be used instead [2, 4]. For our patient,

5.4 mmol/L, respectively, due to unexpected bleeding and we prepared 6 units of packed RBCs and an autologous

presumably intravascular hemolysis. We initiated blood blood salvage device because of the positive irregular

salvage procedures and started transfusion of 2 units of pre- antibody screening result. Autologous blood transfusion

pared packed RBCs using a potassium adsorption filter. can avoid risks or side effects associated with blood

After that, 190 ml of the first salvaged autologous RBCs transfusions. Moreover, the autologous blood salvage

were re-infused. Blood examination results to check K+ device can eliminate over 90% of plasma components [5]

concentration levels in the transfer bag showed a high level presumably including complement factors, which (in

of 6.2 mmol/L in the salvaged RBCs. Because the patient’s theory) would be an added advantage for patients with

Hb became 7.6 g/dL due to continuous bleeding, we trans- PNH, although the RBCs themselves are still vulnerable.

fused two more units of packed RBCs and re-infused 90 ml In the past, over 90% of the K+ in salvaged blood was

of the second salvaged autologous RBCs using a potassium shown to be removed by the wash process [the washed

adsorption filter. The value of K+ in the transfer bag of the RBCs were left with 1–2 mmol/L of (K+)] [6], but in

second salvaged autologous RBCs batch was also high at our case, the K+ concentration in the transfer bag was

6.0 mmol/L. The patient’s Hb level recovered to 10.5 g/dL > 6 mmol/L. This fact indicates that the salvaged blood

after the RBC transfusion. However, the hyperkalemia pro- of patients with PNH continued to be lysed even after

gressed to 6.8 mmol/L of K+, and we administered 850 mg the wash process. Physical stresses, such as infections

of calcium gluconate and initiated glucose-insulin therapy. and surgery, can cause complement activation [7]. In

Although the operation was close to being finished, we addition, the unwashed salvaged blood contains in-

transfused two more units of packed RBCs anticipating the creased levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as

possibility of intravascular hemolysis after the operation. interleukin-1β, 6, and 8, and activated complement

The surgery was performed without complications. The components compared to the circulatory blood [8, 9].

value of K+ at the end of the operation was 4.9 mmol/L. We suspect the hemolysis in our patient was caused by

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Kawamoto et al. BMC Anesthesiology (2019) 19:83 Page 3 of 4

Fig. 1 a Intraoperative progress. b Postoperative progress

surgical stress or surgical inflammation as the K+ con- inhibits C5, resulting in the inhibition of MAC formation

centration increased gradually during the operation. and the effect of eculizumab is remarkable [1, 10, 11].

The attack to the RBCs by the activated complement Although further reports are needed, if eculizumab had

may have proceeded also in the reservoir of blood been used in the present case, the results might have been

salvage device. The level of activated proinflammatory different.

cytokines and activated complement in the salvaged Based on our experience, packed RBCs using a potas-

blood is reduced by the wash [8]; however, once the sium adsorption filter, if available, should be preferred to

complement in the patients with PNH becomes acti- autologous blood in case of perioperative transfusion in

vated and starts forming MAC on the RBCs during the patients with PNH. Kathirvel S et al. has mentioned that

processes of the operation and blood salvage, the in general unwashed RBCs can be used without prob-

hemolytic reaction may not be stopped even with the lems, but for large blood transfusion volumes, the RBCs

washing procedure. That is, the MAC on the mem- may need to be washed [12]. Some anesthesiologists

brane of RBCs does not get washed off. Recently, eculi- may consider the use of washed autologous RBCs under

zumab, a monoclonal antibody to the complement some situations, such as massive hemorrhage or exist-

component 5 (C5), is widely used in PNH therapy. ence of irregular antibodies; however, a pitfall lurks in

However, not all the patients with PNH are adminis- the autologous RBCs of the patients with PNH. The

tered eculizumab because of several reasons such as in- washed autologous RBCs may transiently guarantee oxy-

dication, insurance, and patients’ choice. Eculizumab gen transport to the tissues, but the salvaged RBCs in

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Kawamoto et al. BMC Anesthesiology (2019) 19:83 Page 4 of 4

patients with PNH will become the target of the comple- 6. Serrick CJ, Scholz M, Melo A, Singh O, Noel D. Quality of red blood cells

ment and will get lysed again after the transfusion. using autotransfusion devices: a comparative analysis. J Extra Corpor

Technol. 2003;35:28–34.

Conclusively, packed RBCs instead of salvaged autolo- 7. Lewis RE Jr, Cruse JM, Richey JV. Effects of anesthesia and operation on the

gous RBCs should be used for transfusions in patients classical pathway of complement activation. Clin Immunol Immunopathol.

with PNH. The use of salvaged autologous RBCs in pa- 1982;23:666–71.

8. Tylman M, Bengtson JP, Bengtsson A. Activation of the complement system

tients with PNH should be limited to critical situations by different autologous transfusion devices: an in vitro study. Transfusion.

such as massive bleeding and physicians should keep in 2003;43:395–9.

mind that the hemolytic reaction may be present inside 9. Sieunarine K, Wetherall J, Lawrence-Brown MM, Goodman MA, Prendergast

FJ, Hellings M. Levels of complement factor C3 and its activated product,

the transfer bag even after the wash process. C3a, in operatively salvaged blood. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991;61:302–5.

10. Luzzatto L, Risitano AM, Notaro R. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Abbreviations and eculizumab. Haematologica. 2010;95:523–6.

PNH: Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; GPI: Glycosylphosphatidylinositol; 11. Parker C. Eculizumab for paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Lancet.

DAF: Decay-accelerating factor; RBCs: Red blood cells; MAC: Membrane-attack 2009;373:759–67.

complex; K+: Potassium; ICU: Intensive care unit; POD: Postoperative day 12. Kathirvel S, Prakash A, Lokesh BN, Sujatha P. The anesthetic management of

a patient with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Anesth Analg. 2000;

Acknowledgments 91:1029–31 table of contents.

The authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English

language review.

Funding

This case report was not supported by any funding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this

published article.

Authors’ contributions

YK was the main anesthesiologist of this case and wrote the manuscript

draft. TN coordinated and completed the manuscript. AW was the second

anesthesiologist for this case. KN and AK directed anesthesia management in

this case. TH, NA, SK, and KI supported perioperative management. YT and

TY edited manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors obtained informed consent from the patient regarding the

publication of this case report and the use of related data by written form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author details

1

Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Ehime University

Graduate School of Medicine, Shitsukawa, Toon, Ehime 791-0295, Japan.

2

Department of Anesthesiology, Ehime Prefectural Imabari Hospital, Imabari,

Ehime, Japan. 3Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine,

Kawasaki Medical School, Kurashiki, Okayama, Japan.

Received: 7 January 2019 Accepted: 9 May 2019

References

1. Brodsky RA. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2014;124:2804–11.

2. Brecher ME, Taswell HF. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and the

transfusion of washed red cells. A myth revisited. Transfusion. 1989;29:681–5.

3. Dacie JV. Transfusion of saline-washed red cells in nocturnal

haemoglobinuria (Marchiafava-Micheli disease). Clin Sci. 1948;7:65–75.

4. Rosse WF. Transfusion in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. To wash or

not to wash? Transfusion. 1989;29:663–4.

5. Overdevest EP, Lanen PW, Feron JC, van Hees JW, Tan ME. Clinical

evaluation of the Sorin Xtra(R) autotransfusion system. Perfusion.

2012;27:278–83.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions

Springer Nature journal content, brought to you courtesy of Springer Nature Customer Service Center GmbH (“Springer Nature”).

Springer Nature supports a reasonable amount of sharing of research papers by authors, subscribers and authorised users (“Users”), for small-

scale personal, non-commercial use provided that all copyright, trade and service marks and other proprietary notices are maintained. By

accessing, sharing, receiving or otherwise using the Springer Nature journal content you agree to these terms of use (“Terms”). For these

purposes, Springer Nature considers academic use (by researchers and students) to be non-commercial.

These Terms are supplementary and will apply in addition to any applicable website terms and conditions, a relevant site licence or a personal

subscription. These Terms will prevail over any conflict or ambiguity with regards to the relevant terms, a site licence or a personal subscription

(to the extent of the conflict or ambiguity only). For Creative Commons-licensed articles, the terms of the Creative Commons license used will

apply.

We collect and use personal data to provide access to the Springer Nature journal content. We may also use these personal data internally within

ResearchGate and Springer Nature and as agreed share it, in an anonymised way, for purposes of tracking, analysis and reporting. We will not

otherwise disclose your personal data outside the ResearchGate or the Springer Nature group of companies unless we have your permission as

detailed in the Privacy Policy.

While Users may use the Springer Nature journal content for small scale, personal non-commercial use, it is important to note that Users may

not:

1. use such content for the purpose of providing other users with access on a regular or large scale basis or as a means to circumvent access

control;

2. use such content where to do so would be considered a criminal or statutory offence in any jurisdiction, or gives rise to civil liability, or is

otherwise unlawful;

3. falsely or misleadingly imply or suggest endorsement, approval , sponsorship, or association unless explicitly agreed to by Springer Nature in

writing;

4. use bots or other automated methods to access the content or redirect messages

5. override any security feature or exclusionary protocol; or

6. share the content in order to create substitute for Springer Nature products or services or a systematic database of Springer Nature journal

content.

In line with the restriction against commercial use, Springer Nature does not permit the creation of a product or service that creates revenue,

royalties, rent or income from our content or its inclusion as part of a paid for service or for other commercial gain. Springer Nature journal

content cannot be used for inter-library loans and librarians may not upload Springer Nature journal content on a large scale into their, or any

other, institutional repository.

These terms of use are reviewed regularly and may be amended at any time. Springer Nature is not obligated to publish any information or

content on this website and may remove it or features or functionality at our sole discretion, at any time with or without notice. Springer Nature

may revoke this licence to you at any time and remove access to any copies of the Springer Nature journal content which have been saved.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, Springer Nature makes no warranties, representations or guarantees to Users, either express or implied

with respect to the Springer nature journal content and all parties disclaim and waive any implied warranties or warranties imposed by law,

including merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

Please note that these rights do not automatically extend to content, data or other material published by Springer Nature that may be licensed

from third parties.

If you would like to use or distribute our Springer Nature journal content to a wider audience or on a regular basis or in any other manner not

expressly permitted by these Terms, please contact Springer Nature at

onlineservice@springernature.com

You might also like

- Slide Kuliah Transfusi DarahDocument31 pagesSlide Kuliah Transfusi Darahfenti nurul khafifahNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Lessons From Derivatives MishapsDocument3 pagesAssignment 3 Lessons From Derivatives MishapsSandip Chovatiya100% (2)

- KAR Products - Hi Temp Industrial Anti-SeizeDocument6 pagesKAR Products - Hi Temp Industrial Anti-Seizejaredf@jfelectric.comNo ratings yet

- Firm AnalysisDocument7 pagesFirm Analysisapi-518500123100% (1)

- Acute Oxaliplatin-Induced Hemolytic Anemia, Thrombocytopenia, and Renal Failure: Case Report and A Literature ReviewDocument3 pagesAcute Oxaliplatin-Induced Hemolytic Anemia, Thrombocytopenia, and Renal Failure: Case Report and A Literature ReviewNurul Kamilah SadliNo ratings yet

- 7: Effective Transfusion in Surgery and Critical CareDocument16 pages7: Effective Transfusion in Surgery and Critical CareNick-Hugh Sean WisdomNo ratings yet

- SLED Vs CRRT PDFDocument9 pagesSLED Vs CRRT PDFquilino2012No ratings yet

- Influence of Dry Weight Reduction On Anemia in Patients Undergoing HemodialysisDocument12 pagesInfluence of Dry Weight Reduction On Anemia in Patients Undergoing HemodialysisFajar JarrNo ratings yet

- 2015 Haemostatic Management of Cardiac Surgical HaemorrhageDocument12 pages2015 Haemostatic Management of Cardiac Surgical HaemorrhageDidier AdodoNo ratings yet

- 10 1097MD 0000000000000587Document3 pages10 1097MD 0000000000000587abbasamiri135103No ratings yet

- Niknam 2019Document8 pagesNiknam 2019Valdir ReisNo ratings yet

- Transfusion Guidelines HemDocument4 pagesTransfusion Guidelines HemnandhinisankaranNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument10 pagesResearch ArticleAnonymous SbnDyANo ratings yet

- Blood Conservation in Pediatric Cardiac SurgeryDocument5 pagesBlood Conservation in Pediatric Cardiac Surgerymohanakrishna007No ratings yet

- Effects of Cardiopulmonary Bypass On Mediastinal Drainage and The Use of Blood Products in The Intensive Care Unit in 60-To 80-Year-Old Patients Who Have Undergone Coronary Artery Bypass GraftingDocument8 pagesEffects of Cardiopulmonary Bypass On Mediastinal Drainage and The Use of Blood Products in The Intensive Care Unit in 60-To 80-Year-Old Patients Who Have Undergone Coronary Artery Bypass GraftingYogi TrilaksonoNo ratings yet

- The Open Anesthesia JournalDocument11 pagesThe Open Anesthesia JournalmikoNo ratings yet

- A. 24 Hours Pre-Operatively B. 2 Hours Pre-Operatively C. Whilst Making The Skin IncisionDocument75 pagesA. 24 Hours Pre-Operatively B. 2 Hours Pre-Operatively C. Whilst Making The Skin Incision5alifa55No ratings yet

- Aliment Pharmacol Ther - 2022 - Tergast - Home Based Tunnelled Peritoneal Drainage System As An Alternative TreatmentDocument11 pagesAliment Pharmacol Ther - 2022 - Tergast - Home Based Tunnelled Peritoneal Drainage System As An Alternative TreatmentTens AiepNo ratings yet

- Refractory Septic ShockDocument5 pagesRefractory Septic ShockBrian Antonio Veramatos LopezNo ratings yet

- Rituximab (Mabthera) SD Antifosfolipidos 4Document7 pagesRituximab (Mabthera) SD Antifosfolipidos 4AlexNo ratings yet

- BR J Haematol - 2009 - DIC MXDocument10 pagesBR J Haematol - 2009 - DIC MXAdil EissaNo ratings yet

- Critical Care 123Document66 pagesCritical Care 123Mr.ShazNo ratings yet

- Briggs2006 PDFDocument10 pagesBriggs2006 PDFRonal WinterNo ratings yet

- Hypervolemia Increases Release of Atrial Natriuretic Peptide and Shedding of The Endothelial GlycocalyxDocument8 pagesHypervolemia Increases Release of Atrial Natriuretic Peptide and Shedding of The Endothelial GlycocalyxbayanganNo ratings yet

- Small Volume Resuscitation With 20 Albumin in Intensive Care Physiological EffectsDocument10 pagesSmall Volume Resuscitation With 20 Albumin in Intensive Care Physiological EffectsDr. Prashant KumarNo ratings yet

- Massive Transfusion - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument6 pagesMassive Transfusion - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfsadam sodomNo ratings yet

- TRF 14043Document10 pagesTRF 14043Ahmad ANo ratings yet

- BloodDocument7 pagesBloodWael AlmahdiNo ratings yet

- PIIS0007091222006201Document10 pagesPIIS0007091222006201Xavi Navarro FontNo ratings yet

- Evidencia Transfusion HemoderivadosDocument13 pagesEvidencia Transfusion HemoderivadosHernando CastrillónNo ratings yet

- TMP 9 B42Document6 pagesTMP 9 B42FrontiersNo ratings yet

- NIGAMDocument5 pagesNIGAMameenNo ratings yet

- Impact of Albumin RL For BTDocument10 pagesImpact of Albumin RL For BTSandeep BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- TransfusiDocument9 pagesTransfusiabbhyasa5206No ratings yet

- Vasoplegic SyndromeDocument41 pagesVasoplegic SyndromeFaizan Ahmad Ali100% (1)

- Guidline Penanganan Aplastic Anemia PDFDocument28 pagesGuidline Penanganan Aplastic Anemia PDFkeyla_shineeeNo ratings yet

- Washed Red Cells: Theory and Practice: Review ArticleDocument11 pagesWashed Red Cells: Theory and Practice: Review Articlemy accountNo ratings yet

- Management of A Kaposiform Haemangioendothelioma of T - 2016 - Pediatric HematolDocument4 pagesManagement of A Kaposiform Haemangioendothelioma of T - 2016 - Pediatric HematolHawin NurdianaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Red Cell Rejuvenation Versus Mechanical Washing For The Prevention of Transfusion-Associated Organ Injury in SwineDocument11 pagesA Comparison of Red Cell Rejuvenation Versus Mechanical Washing For The Prevention of Transfusion-Associated Organ Injury in Swinealfrilia0843No ratings yet

- Preoptimisation of Haemoglobin: General Anaesthesia Tutorial 389Document5 pagesPreoptimisation of Haemoglobin: General Anaesthesia Tutorial 389bobbykrishNo ratings yet

- Blood ProductsDocument41 pagesBlood ProductsrijjorajooNo ratings yet

- An International Consensus Statement On The Management of Postoperative Anaemia After Major Surgical ProceduresDocument14 pagesAn International Consensus Statement On The Management of Postoperative Anaemia After Major Surgical ProceduresEdwin PradanaNo ratings yet

- Intermittent Hemodialysis For Managing Metabolic Acidosis During Resuscitation of Septic Shock: A Descriptive StudyDocument5 pagesIntermittent Hemodialysis For Managing Metabolic Acidosis During Resuscitation of Septic Shock: A Descriptive Studyilham masdarNo ratings yet

- PEG-conjugated Hemoglobin Combination With Cisplatin Enforced The Antiangiogeic Effect in A Cervical Tumor Xenograft ModelDocument12 pagesPEG-conjugated Hemoglobin Combination With Cisplatin Enforced The Antiangiogeic Effect in A Cervical Tumor Xenograft ModelIstván PortörőNo ratings yet

- Canine Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia Treatment and PrognosisDocument10 pagesCanine Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia Treatment and PrognosisDiana LoayzaNo ratings yet

- Blood and Blood Product (F)Document50 pagesBlood and Blood Product (F)bharat singhNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionsDocument52 pagesBlood TransfusionsZuhri RomiNo ratings yet

- Dgac 201Document8 pagesDgac 201Reinaldi octaNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia - 2018 - Mu OzDocument14 pagesAnaesthesia - 2018 - Mu OzCarp TheodorNo ratings yet

- MJCU_Volume 88_Issue December_Pages 2121-2129Document9 pagesMJCU_Volume 88_Issue December_Pages 2121-2129jihansalma00No ratings yet

- MainDocument8 pagesMainAdityaRestuRahayuNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass A SystematicDocument21 pagesAnesthetic Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass A SystematicFabio MeloNo ratings yet

- Extracorporeal Photopheresis in Pediatric Patients Practical and Technical ConsiderationsDocument10 pagesExtracorporeal Photopheresis in Pediatric Patients Practical and Technical Considerationselenaa.hp28No ratings yet

- Case Study Residency2Document21 pagesCase Study Residency2computerwhiz42985No ratings yet

- DrHSMurthy HiPECDocument11 pagesDrHSMurthy HiPECReddyNo ratings yet

- 14 - Mazandarani2012Document7 pages14 - Mazandarani2012TandeanTommyNovenantoNo ratings yet

- A Rare Case of Spontaneous Hepatic Rupture in A Pregnant WomanDocument4 pagesA Rare Case of Spontaneous Hepatic Rupture in A Pregnant WomanFatmawati MahirNo ratings yet

- 1 Transfusion1 PDFDocument7 pages1 Transfusion1 PDFVatha NaNo ratings yet

- Posttransfusion Refractory ThrombocytopeniaDocument19 pagesPosttransfusion Refractory ThrombocytopeniaKyla ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Aliment Pharmacol Ther - 2012 - Restellini - Red Blood Cell Transfusion Is Associated With Increased Rebleeding in Patients PDFDocument7 pagesAliment Pharmacol Ther - 2012 - Restellini - Red Blood Cell Transfusion Is Associated With Increased Rebleeding in Patients PDFzevillaNo ratings yet

- Blood Product Replacement For Postpartum HemorrhageDocument7 pagesBlood Product Replacement For Postpartum HemorrhageAlberto LiraNo ratings yet

- Standard Renal Replacement Therapy Combined With HemoadsorptionDocument8 pagesStandard Renal Replacement Therapy Combined With HemoadsorptionMihai PopescuNo ratings yet

- Article Hysteroscopic Tubal PatencyDocument7 pagesArticle Hysteroscopic Tubal PatencyTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Physiological Control of Mammary Growth, Lactogenesis, and Lactation 1Document19 pagesPhysiological Control of Mammary Growth, Lactogenesis, and Lactation 1Tandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Society For Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #49: Cesarean Scar PregnancyDocument13 pagesSociety For Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) Consult Series #49: Cesarean Scar PregnancyTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Induction of Lactation: Estrogen and Progesterone in Milk IDocument7 pagesHormonal Induction of Lactation: Estrogen and Progesterone in Milk ITandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Uog 20150Document9 pagesUog 20150Tandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Post Ligation Syndrome / Menstrual Disorders After Tubal LigationDocument4 pagesPost Ligation Syndrome / Menstrual Disorders After Tubal LigationTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Pitfalls in The Assessment of Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisDocument7 pagesPitfalls in The Assessment of Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Kinomoto Kondo2016Document7 pagesKinomoto Kondo2016Tandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- Correspondence: Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisDocument1 pageCorrespondence: Gestational Transient ThyrotoxicosisTandyo TriasmoroNo ratings yet

- About Gazi Auto BrickDocument19 pagesAbout Gazi Auto BrickMd. Reza-Ul- HabibNo ratings yet

- Poulos Bill - The Truth About Fibonacci TradingDocument23 pagesPoulos Bill - The Truth About Fibonacci TradingPantera1010No ratings yet

- Report On Financial Analysis of Textile Industry of BangladeshDocument39 pagesReport On Financial Analysis of Textile Industry of BangladeshSaidur0% (2)

- Basic PEAT ManualDocument14 pagesBasic PEAT Manualvanderwalt.paul2286100% (1)

- Curriculum DevelopmentDocument142 pagesCurriculum DevelopmentMark Nel VenusNo ratings yet

- 2 Education FCE SpeakingDocument3 pages2 Education FCE SpeakingMaryna TsehelskaNo ratings yet

- 5 Min FlipDocument76 pages5 Min FlipAnonymous JrCVpuNo ratings yet

- Pro Material Series: Free Placement Video Tutorial With Mock Test VisitDocument10 pagesPro Material Series: Free Placement Video Tutorial With Mock Test VisitPuneethNo ratings yet

- Jose Rizal's Life, Works and Studies in Europe (Part 1)Document5 pagesJose Rizal's Life, Works and Studies in Europe (Part 1)Russen Belen50% (2)

- pCO Electronic Control Chillers Aries Free-CoolingDocument94 pagespCO Electronic Control Chillers Aries Free-CoolingStefania FerrarioNo ratings yet

- Personality and Cultural Values PresentationDocument17 pagesPersonality and Cultural Values PresentationTaimoor AbidNo ratings yet

- HR Om11 ch05Document80 pagesHR Om11 ch05FADHIA AULYA NOVIANTYNo ratings yet

- Brochure Bananas PDFDocument2 pagesBrochure Bananas PDFPorcoddioNo ratings yet

- 3 - SR - Q1 2022 Chicken Egg Situation Report - v2 - ONS-signedDocument6 pages3 - SR - Q1 2022 Chicken Egg Situation Report - v2 - ONS-signedMonette De CastroNo ratings yet

- Science Technology and Society MODULE 3Document7 pagesScience Technology and Society MODULE 3jesson cabelloNo ratings yet

- Greaves Cotton: Upgraded To Buy With A PT of Rs160Document3 pagesGreaves Cotton: Upgraded To Buy With A PT of Rs160ajd.nanthakumarNo ratings yet

- Module 1 STSDocument22 pagesModule 1 STSGinaly Pico100% (1)

- !insanity CalendarDocument5 pages!insanity CalendarOctavio BejaranoNo ratings yet

- Grace Varas, DO UT Health Division of Geriatric & Palliative Medicine, Department of Internal MedicineDocument27 pagesGrace Varas, DO UT Health Division of Geriatric & Palliative Medicine, Department of Internal MedicinePriyesh CheralathNo ratings yet

- Plate Tectonics VocabularyDocument4 pagesPlate Tectonics VocabularyJamela PalomoNo ratings yet

- FarnchiseeDocument31 pagesFarnchiseeSk DadarNo ratings yet

- Convertible Note Agreement - SkillDzireDocument16 pagesConvertible Note Agreement - SkillDzireMAツVIcKYツNo ratings yet

- Shani Sadhe Sati and DhaiyaDocument2 pagesShani Sadhe Sati and DhaiyaSanjay DhimanNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning For EveryoneDocument3 pagesMachine Learning For Everyonejppn33No ratings yet

- Palayan CDP Final PpdoDocument109 pagesPalayan CDP Final PpdoMargarita AngelesNo ratings yet

- Sharjaa CarbonatesDocument190 pagesSharjaa CarbonatesRuben PradaNo ratings yet

- There Ain't No Cure For Love: The Psychotherapy of An Erotic TransferenceDocument7 pagesThere Ain't No Cure For Love: The Psychotherapy of An Erotic TransferenceВасилий МанзарNo ratings yet