Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DD Gout-Kiefer 2023

DD Gout-Kiefer 2023

Uploaded by

Suryo HardjoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DD Gout-Kiefer 2023

DD Gout-Kiefer 2023

Uploaded by

Suryo HardjoCopyright:

Available Formats

Exploration of Musculoskeletal Diseases

Open Access Case Report

Similarities and differences between gouty arthritis and

rheumatoid arthritis—an interesting case with a short look into

the literature

David Kiefer†* , Judith Erkenberg†, Juergen Braun†

Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet, Ruhr-University Bochum, 44649 Herne, Germany

†

These authors contributed equally to this work.

*Correspondence: David Kiefer, Rheumazentrum Ruhrgebiet, Ruhr-University Bochum, Claudiusstrasse 45, 44649 Herne,

Germany. david.kiefer@elisabethgruppe.de

Academic Editor: Peter Mandl, Medical University of Vienna (MUW), Austria

Received: August 5, 2022 Accepted: January 3, 2023 Published: February 24, 2023

Cite this article: Kiefer D, Erkenberg J, Braun J. Similarities and differences between gouty arthritis and rheumatoid

arthritis—an interesting case with a short look into the literature. Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9.

https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003

Abstract

Gout often presents as acute arthritis but may also present with chronic joint inflammation. For the diagnosis

of an acute gout attack with its typical symptoms, the differentiation towards a bacterial joint infection is

critical and mandatory. The detection of intracellular uric acid crystals in the synovial fluid of affected

joints is important for the initial diagnosis of gout. In the case of a chronic course with polyarticular

joint involvement, the differentiation from other inflammatory rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid

arthritis (RA) can be challenging. The case presented here is of interest because the patient initially had

characteristic clinical symptoms of tophaceous gout including a typical medical history—even though

rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (anti-CCP) were positive. The course of the

disease and the critical evaluation of all findings also, and most interestingly, including histological results

finally suggested a main diagnosis of RA.

Keywords

Arthritis urica, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid nodule, tophus, polyarthritis

Introduction

Arthritis due to gout, spondyloarthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is, with a prevalence of roughly 1%

for RA and a range from < 1% to 6.8%, depending on different study populations for gout, the most common

causes of arthritis worldwide [1–6]. An acute gouty attack with its typical symptoms, in form of severe

pain with redness and swelling of the typically affected joints, represents a diagnostic challenge only in so

far as a bacterial infection has to be excluded, and the gain of synovial or tophaceous material is sometimes

not trivial. This matters for the diagnosis, since the ultimate proof of gout does rely on the intraarticular

detection of urate crystals. The diagnosis is more difficult in chronic disease stages with a polyarticular

course, and in some cases even in the tophaceous stage [7]. In this case, it is often not so easy to distinguish

© The Author(s) 2023. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution

and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the

original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 11

chronic gout from RA [8–11]—especially since both diseases may, reportedly, occur together [12, 13]. This

case report is meant to serve as a basis to discuss differential diagnostic problems of gouty arthritis.

Classical gout (arthritis urica) is characterized by an acute attack of mon- or oligoarthritis with redness,

swelling, and severe pain which may occur after excessive alcohol and/or meat intake or during/after

fasting. The serum uric acid level is often but not always elevated in acute attack. Normally the differential

diagnosis is more difficult. There is quite some tropism in gout: the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint

is frequently affected, but other joints such as knee or ankle joints may also be affected. In the early phases

of the disease, gout occurs mainly as mono- or oligoarthritis, mainly in the lower extremities, and later

increasingly as polyarthritis, also in the upper extremities. Extra-articular manifestations include bursitides

of the elbow (bursitis olecrani) and knee (bursitis praepatellaris) are quite common—as are insertional

tendinopathies of the Achilles and patellar tendons. The chronic, tophaceous and/or erosive course

of gouty arthritis usually occurs only after long persistent hyperuricemia [7]. This results in the tissue

deposition of sodium urate, which may occur intra- and periarticularly but also in other soft tissues where

it potentially becomes visible as gout tophi. In the chronic course of the disease, the frequency of gout attacks

increases and the recurrent arthritis does not infrequently lead to joint destruction resulting in functional

deficits. In acute and chronic gout, inflammatory serum markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) are usually

markedly elevated. Chronic renal insufficiency may be the cause of hyperuricemia but also comorbidity like

cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome which commonly occur together.

In addition to the acute management with colchicine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (in

case of normal renal function) and glucocorticoids administered both, intraarticularly and systemically,

anti-interleukin-1 (anti-IL-1) directed biologic agents may be indicated and used in more severe cases.

This part of the treatment strategy is acute and anti-inflammatory aiming to reduce pain and abolish

inflammation. In parallel, preventive therapeutic strategies are started to permanently lower serum uric acid

levels to reduce gout attacks and decrease the number and size of tophi. For this purpose, urate-lowering

treatment with xanthine oxidase inhibitors such as allopurinol and febuxostat is most commonly used.

The management of gout can be challenging for multiple reasons [14]. To ascertain the diagnosis of

gout, the current gold standard is the detection of uric acid crystals in the synovial fluid, in periarticular

tissues, or directly in tophi. Unfortunately, arthrocentesis is often not possible for technical and

other reasons such as patients’ pain. Imaging techniques such as arthrosonography have been shown to

potentially support a diagnosis of gout since the detection of the so-called double contour phenomenon at

the articular cartilage as well as topheous deposits and/or bony erosions, preferentially located peri- or

intraarticularly—so-called punched-out lesions are suggestive of being caused by gout [8]. Another, relatively

new imaging technique, dual-energy computed tomography (DECT), is a diagnostic tool that can detect uric

acid crystals based on their specific X-ray absorption behavior [14–16].

RA is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease that typically manifests as symmetric polyarthritis.

Wrists, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, and MTP joints are

frequently affected [17]. However, almost all synovial joints can be involved. RA usually manifests with

joint pain and swelling, often associated with morning stiffness exceeding 30 min [18]. Extra-articular

manifestations such as pulmonary involvement are rather frequent but other features such as rheumatoid

nodules and vasculitis are less common. RA usually runs a chronic course potentially leading to

joint destruction, tendon rupture, deformities, and functional loss leading to reduced physical activity

and participation. Risk factors for an aggressive erosive course of RA are in particular seropositivity

with autoantibodies to immunoglobulin G (rheumatoid factor) and/or to anti-citrullinated protein

antibodies (anti-CCP) as well as smoking and elevated acute phase reactants [17, 19, 20].

Immunomodulatory drugs are the backbone of treatment which are supposed to reduce

inflammation and prevent structural damage to joints and tendons in RA. In case this is proven, they are

named disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). They are conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs),

such as methotrexate with a not completely clarified mode of action, or biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs), such

as the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors and targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) such as the

Janus-kinase (JAK) inhibitors.

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 12

Some clinical differences between chronic tophaceous gout and RA are listed in Table 1. The initial

therapeutic strategies comprise non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and glucocorticoids usually

lead to rapid improvement of symptoms. However, since the other targeted therapeutic strategies differ

substantially a solid confirmation of the diagnosis is mandatory and much wanted by the responsible

rheumatologist and/or general practitioner [14, 21].

Table 1. Summary of similarities and differences between acute and chronic gout and RA

Symptoms and diagnostics Acute gout attack Chronic tophaceous gout RA

Clinical pattern Frequently monoarthritis, large Frequently polyarticular, soft Symmetrical, mostly small

joints such as knee, ankle, and tissue tophi joints (MCP, PIP, MTP, wrists),

MTP joint ulnar deviation, swan neck

deformity, buttonhole deformity,

rheumatoid foot deformity

Symptoms Redness, swelling, pain, Redness, swelling, pain, Swelling, pain, stiffness

possibly fever possibly fever

Extraarticular manifestation Subcutaneous edema due Bursa, tendon and soft Bursa, tendons, vessels,

to inflammation tissue involvement, serous membranes, pulmonary

extraarticular tophi involvement, vasculitis

Joint ultrasound Double contour sign, synovitis, Double contour sign, Synovitis, positive power doppler

positive power doppler signal synovitis, positive power erosions, structural damage

doppler signal, effusion

tophi, punched-out lesions

X-ray Initially often no bony changes, Tophi, soft tissue tophi, Soft tissue swelling,

soft tissue swelling punched-out lesions structural changes like

erosions, subluxations,

deformation, ankyloses

Dual energy computed Urat crystals are detectable, Urat crystals are detectable Osteitis in the form of bone

tomography (CT) but in early stages (usually < 6 if the mass of crystals is marrow edema, synovitis,

weeks) the DECT may show high enough synovial fluid, structural changes

false negative results

Synovial fluid analysis Inflammatory synovial Inflammatory synovial fluid Inflammatory synovial fluid with

fluid (usually increased with mostly increased cell mostly increased cell count

leukocyte count and a high count and detection of

percentage of granulocytes urate crystals in polarized

and rhagocytes) and detection light microscopy

of negative birefringence

crystals in polarized

light microscopy

Histology rheumatoid Evidence of urate crystals Evidence of urate crystals Central fibrinoid necrosis

nodules/gouty tophus surrounded by histiocytes and

epithelioid cells

Case report

History: A 47-year-old man presented to a specialized hospital with pain and swelling of elbows, wrists,

and feet which had first appeared about 3 years ago. The complaints were first described as more like acute

attacks and later as both, attack-like and persistent. The patient also reported morning stiffness of about

30 min and alcohol abuse, preferably vodka, on a daily basis, frequent use of soft drinks, and a meat-enriched

diet. Clinically, podagra of the right big toe and swelling of both elbows with palpable solid structures in the

olecranon bursa and the forearm were suggestive of gout tophi (Figure 1). Informed consent for publication

was obtained from the participant.

Diagnostics

The uric acid level was normal (6.3 mg/dL), and CRP was slightly elevated (1.1 mg/dL, normally

< 0.5 mg/dL) with a rather normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 22 mm/1 h. Rheumatoid

factor (418 IU/mL, normally < 14 IU/mL) and anti-CCP antibodies were detected in high titers (236 IU/mL,

normally < 40 IU/mL).

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 13

Figure 1. Left elbow with significant soft tissue thickening (blue arrows)

A conventional radiograph revealed tophus-suspect soft tissue compaction lateral to the 5th MTP in

both feet accentuated on the right, as well as tophus-suspect soft tissue compaction medial to the first

MTP on the right (Figure 2). By magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), an oval structure, approximately 3 cm in

size, was seen ventral to the right proximal tibia in the subcutaneous adipose tissue, which morphologically

appeared as an intermediate to low signal on a T1 weighted image, possibly an intratenosynovial

tophus (Figure 3). In addition, peritenosynovial inflammation and a soft tissue spot suggestive of another

tophus at the right flexor hallucis longus tendon were seen. However, no structure suggestive of urate in that

region was detected by DECT. A massive tophus-suspect soft tissue compression or swelling dorsal to the left

elbow, and, correspondingly, on the right proximal ulna could, unfortunately, not be punctured because the

patient didn’t consent.

Figure 2. X-ray. A) X-ray (anterior-posterior) of the left elbow without erosive changes but massive tophus suspected soft tissue

thickening (blue arrow); B) radiograph of the right foot anterior-posterior with tophus suspected soft tissue thickening lateral to the

MTP5 joint and erosions/usures of the MTP5 head (yellow arrow). Tophus suspicious soft tissue thickening medial of MTP1 and

MTP1 head with medial small erosions (red arrow); C) radiograph of the lateral upper ankle with tophus and soft tissue thickening

ventral to the right-proximal tibia in subcutaneous fat (green arrow)

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 14

Figure 3. MRI of the right foot. A) T1 weighting transversal: small marginal erosion head MTP1 medial, soft tissue plus compatible

with tophus medial of head MTP1 (white arrows); B) T1 with contrast transversal: synovialitis MTP1 (orange arrow); C) T1 with

contrast sagital: severe tenovaginitis of tibialis anterior tendon intratenosynovial signal-poor structures as in intratenosynovial

tophus (yellow arrow)

In addition, X-rays of the forefeet showed small and larger erosions on the left and right MTP1 joint, as

well as on the left basophalanx base DII and right MTP5 (Figure 2).

Diagnosis

The summarization of all findings of the clinical pictures was interpreted as typical for advanced erosive

tophaceous gout.

Therapy and course

A therapy with celecoxib [200 mg once a day (OD)], prednisolone (decreasing from 30 mg), colchicine, and

pantoprazol 40 mg/day was started. Allopurinol [300 mg twice a day (BID)] had already been initiated by

the primary care physician several weeks ago. There was a rapid clinical improvement of pain and reduction

of inflammation. However, due to the positive rheumatoid factors, the radiographically detected erosions,

and the negative DECT, there was residual diagnostic uncertainty and, since an elective bursectomy of the

left elbow had to be performed within a few days, a biopsy was taken during the operation (Figure 4). The

pathologic evaluation of the biopsy sample revealed chronic florid abortive granulomatous bursitis, most

compatible with rheumatoid granuloma, with, again, no evidence of uric acid crystals (Figure 5). Thus, the

diagnosis was changed to seropositive RA, and accordingly, therapy with methotrexate was started. In

parallel, inpatient treatment of the alcoholic disease was initiated. The patient presented with just a few

complaints but no more arthralgia in an outpatient control visited 3 months later.

Figure 4. Arthroscopic findings of the left elbow with nodular soft tissue changes (blue arrows)

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 15

Figure 5. Histology. Histology of left elbow: portions of a fibrous bursal wall with rich capillarization and follicularly organized fibrin

clots, marginal small fibrinoid necrosis zone due to wall-like granulation tissue, overall consistent with rheumatoid granuloma

Discussion

The reason for publishing this case is to draw attention to the from time to time difficult differential diagnosis

between chronic gout and RA. Our clinical findings of this patient initially seemed to favor a diagnosis of

gout but the histology taken from the left olecranon bursa told a different story making RA the more likely

diagnosis. However, a mixed picture and the presence of two diagnoses in consideration of the lifestyle of

this patient and the initially typical podagra are still possible and cannot be excluded. This case reminds us

that, even with rather typical manifestations of a clinical picture, the possible differential diagnosis has to be

critically discussed, and even though histology is usually not needed to diagnose RA, in special cases as here,

it might be useful. Since the clinical picture of RA and gout, especially in chronic cases, can be rather similar,

imaging techniques such as MRI and DECT can be helpful for the differential diagnosis but arthrocentesis to

be able to examine synovial fluid and sometimes even a biopsy to allow for histologic analyses may still be

important for a correct diagnosis. The patient presented here may possibly even suffer from both diseases

which may become more apparent in the course of the disease. At present, the patient is in remission

regarding his RA and his uric acid level has remained < 5 mg/dL.

For many years the common opinion was that gout and RA rarely coexist but only a few studies have

been performed. Several hypotheses related to the pathogenesis were put forward some decades ago, none of

which turned out to be true. These included the binding of rheumatoid factor to urate crystals could block their

surface activity [22, 23], or hyperuricemia directly inhibiting the secondary polyarthritis [24], for example,

because of antioxidant effects [25]. In conclusion, there is no evidence of whether and how the pathogenetic

effects of these two diseases could possibly influence each other. However, data is suggesting that RA and

gout do coexist and some even found an increased prevalence compared to the general population.

Indeed, in one population-based retrospective study which confirmed the rare coexistence of these two

diseases a lower prevalence of gout was found in RA patients compared to the general population [26]. In

contrast, in a population-based cross-sectional study from Israel using a medical database with > 11,000 RA

patients and > 50,000 controls the proportion of patients with concomitant gout (1.61%) was significantly

higher than in controls (0.92%), and, by multivariate analysis, RA was even found to be associated with

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 16

gout [odds ratio (OR) = 1.72, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.45–2.05], however, database analyses like this

are known to methodologically suffer from the general lack of ascertainment which seems to be especially

critical with the study question asked here [12]. In a longitudinal study with almost 2,000 RA patients,

a high frequency of hyperuricemia (17%) and gout (6%) was reported [27]. A study from New Zealand on

patients with tophaceous gout (the majority being Polynesian or Maori) revealed a prevalence of anti-CCP

antibodies of 4%—this is relatively rare but may occur in patients with tophaceous gout [28]. Both,

monosodium urate crystals and rheumatoid nodules, were detected in the biopsy material of the knee joint

of a 42-year-old patient presenting with multiple subcutaneous nodules and intermittent episodes of acute

arthritis [29]. Using DECT, it was recently shown that many RA patients with concomitant hyperuricemia

had periarticular monosodium urate crystal deposits in hand and foot joints [30]. However, whether these

findings contribute to the clinical symptoms of the patients is not clear. In addition, this may be similar to

other diseases such as osteoarthritis.

Several case reports and series of RA and gout appearing concomitantly have been published, in some

cases, the RA started earlier, and in others, it was gout [13, 22–24, 31–34]. This supports the hypothesis

that the simple explanation is that they may just occur together because of their relatively high prevalence

in the population (both about 1%).

These data indicate that, contrary to popular beliefs, RA and gout do coexist in patients [31], and this

may even be more frequent than previously thought. Thus, this knowledge and awareness are important for

finding solutions in difficult clinical cases and for good treatment decisions.

In summary, the differential diagnosis between RA and chronic gout, both rather frequent rheumatic

diseases, can be challenging, and the diseases may even occur in parallel—with no rules about which one

comes first. The here presented case describes the clinical problems and challenges associated with the

differential diagnosis of RA vs. gout. The case also shows that the first diagnosis doesn’t always stay the same

in the course of the disease and that in the management of rheumatic diseases, all available evidence may be

needed to solve clinical problems and draw meaningful conclusions.

Abbreviations

anti-CCP: anti-citrullinated protein antibodies

DECT: dual-energy computed tomography

DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging

MTP: metatarsophalangeal

RA: rheumatoid arthritis

Declarations

Author contributions

DK: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. JE: Conceptualization,

Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. JB: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft,

Writing—review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 17

Consent to publication

Informed consent to publication was obtained from relevant participants.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2023.

References

1. Schmidt CO, Gunther KP, Goronzy J, Albrecht K, Chenot JF, Callhoff J, et al. Frequencies of

musculoskeletal symptoms and disorders in the population-based German National Cohort (GNC).

Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2020;63:415–25. German.

2. Annemans L, Spaepen E, Gaskin M, Bonnemaire M, Malier V, Gilbert T, et al. Gout in the UK and

Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Ann Rheum Dis.

2008;67:960–6.

3. McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2205–19.

4. Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, Bardin T, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al.; EULAR Standing Committee

for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeuti. EULAR evidence based recommendations for

gout. Part I: diagnosis. Report of a task force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical

Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1301–11.

5. Mikuls TR, Farrar JT, Bilker WB, Fernandes S, Schumacher HR Jr, Saag KG. Gout epidemiology: results

from the UK General Practice Research Database, 1990–1999. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:267–72.

6. Dehlin M, Jacobsson L, Roddy E. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence, treatment patterns

and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16:380–90.

7. Bursill D, Taylor WJ, Terkeltaub R, Abhishek A, So AK, Vargas-Santos AB, et al. Gout, Hyperuricaemia

and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN) consensus statement regarding labels and

definitions of disease states of gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1592–600.

8. Bastian H, Ziegeler K, Hermann K, Feist E. Rheumatoid arthritis – mimics. Z Rheumatol. 2019;78:6–13.

9. Chakradeo K, Buzacott K, Soden M. Nodular rheumatoid arthritis resembling gout. BMJ Case Rep.

2016;2016:bcr2016216967.

10. Schapira D, Stahl S, Izhak OB, Balbir-Gurman A, Nahir AM. Chronic tophaceous gouty arthritis

mimicking rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1999;29:56–63.

11. Sewell KL, Petrucci R, Keiser HD. Misdiagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis in an elderly woman with gout.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:403–6.

12. Merdler-Rabinowicz R, Tiosano S, Comaneshter D, Cohen AD, Amital H. Comorbidity of gout and

rheumatoid arthritis in a large population database. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:657–60.

13. Kuo CF, Tsai WP, Liou LB. Rare copresent rheumatoid arthritis and gout: comparison with pure

rheumatoid arthritis and a literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:231–5.

14. Kiltz U, Smolen J, Bardin T, Cohen Solal A, Dalbeth N, Doherty M, et al. Treat-to-target (T2T)

recommendations for gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:632–8.

15. Rajiah P, Sundaram M, Subhas N. Dual-energy CT in musculoskeletal imaging: what is the role beyond

gout? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213:493–505.

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 18

16. Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, Fransen J, Schumacher HR, Berendsen D, et al. 2015 gout classification

criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative

initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1789–98. Erratum in: Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:473.

17. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016;388:2023–38. Erratum in: Lancet.

2016;388:1984.

18. Schneider M, Baseler G, Funken O, Heberger S, Kiltz U, Klose P, et al. Management of early rheumatoid

arthritis. Z Rheumatol. 2020;79:1–38.

19. Bellucci E, Terenzi R, La Paglia GM, Gentileschi S, Tripoli A, Tani C, et al. One year in review 2016:

pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:793–801.

20. Chang K, Yang SM, Kim SH, Han KH, Park SJ, Shin JI. Smoking and rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Mol Sci.

2014;15:22279–95.

21. Fiehn C, Holle J, Iking-Konert C, Leipe J, Weseloh C, Frerix M, et al. S2e guideline: treatment of

rheumatoid arthritis with disease-modifying drugs. Z Rheumatol. 2018;77:35–53.

22. Wallace DJ, Klinenberg JR, Morham D, Berlanstein B, Biren PC, Callis G. Coexistent gout and rheumatoid

arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1979;22:81–6.

23. Gordon TP, Ahern MJ, Reid C, Roberts-Thomson PJ. Studies on the interaction of rheumatoid factor with

monosodium urate crystals and case report of coexistent tophaceous gout and rheumatoid arthritis.

Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44:384–9.

24. Lussier A, de Medicis R. Coexistent gout and rheumatoid arthritis: “a red marker?”. Arthritis Rheum.

1979;22:939–40.

25. Agudelo CA, Turner RA, Panetti M, Pisko E. Does hyperuricemia protect from rheumatoid inflammation?

Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:443–8.

26. Jebakumar AJ, Udayakumar PD, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Occurrence of gout in rheumatoid arthritis: it

does happen! A population-based study. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2013;8:433–7.

27. Chiou A, England BR, Sayles H, Thiele GM, Duryee MJ, Baker JF, et al. Coexistent hyperuricemia and gout

in rheumatoid arthritis: associations with comorbidities, disease activity, and mortality. Arthritis Care

Res (Hoboken). 2020;72:950–8.

28. Chow E, Aati O, Dalbeth N, Doyle A, McQueen FM. Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies in tophaceous

gout: prevalence in a polynesian population. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015;21:326–8.

29. Strader KW, Agudelo CA. Coexistence of rheumatoid nodulosis and gout. J Rheumatol. 1986;13:818–20.

30. Petsch C, Araujo EG, Englbrecht M, Bayat S, Cavallaro A, Hueber AJ, et al. Prevalence of monosodium

urate deposits in a population of rheumatoid arthritis patients with hyperuricemia. Semin Arthritis

Rheum. 2016;45:663–8.

31. Olaru L, Soong L, Dhillon S, Yacyshyn E. Coexistent rheumatoid arthritis and gout: a case series and

review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:2835–8.

32. Nordström D, Leirisalo-Repo M, Petterson T. Optimized treatment of a patient having rheumatoid

arthritis and gout at the same time. Duodecim. 2013;129:1045–8.

33. Zhao G, Wang X, Fu P. Recognition of gout in rheumatoid arthritis: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore).

2018;97:e13540.

34. Baker DL, Stroup JS, Gilstrap CA. Tophaceous gout in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Am

Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107:554–6.

Explor Musculoskeletal Dis. 2023;1:11–9 | https://doi.org/10.37349/emd.2023.00003 Page 19

You might also like

- January 2014: Occupational English TestDocument40 pagesJanuary 2014: Occupational English TestNLNo ratings yet

- Gout: The Radiology and The Clinical ManifestationsDocument9 pagesGout: The Radiology and The Clinical ManifestationsDian YazmiatiNo ratings yet

- RA1Document19 pagesRA1Ioana Omnia OkamNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument11 pagesRheumatoid ArthritisAkshayNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument5 pagesRheumatoid ArthritisValerrie NgenoNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument29 pagesRheumatoid ArthritisTamim IshtiaqueNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid Arthritis Module IDocument14 pagesRheumatoid Arthritis Module ISamhitha Ayurvedic ChennaiNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ali's Uworld Notes For Step 2 CKDocument29 pagesDr. Ali's Uworld Notes For Step 2 CKuyes100% (1)

- Case Psoriatic ArthritisDocument5 pagesCase Psoriatic ArthritisAyuNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Various Homoeopathic Trials in Patients of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An UpdateDocument6 pagesFundamentals of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Various Homoeopathic Trials in Patients of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An UpdateHomoeopathic PulseNo ratings yet

- Gout and Othercrystal-Associated ArthropathiesDocument31 pagesGout and Othercrystal-Associated ArthropathiesLia pramitaNo ratings yet

- Got ADocument5 pagesGot AViribu GaliciaNo ratings yet

- Kristal Artropati KuliahDocument36 pagesKristal Artropati KuliahRoby KieranNo ratings yet

- AR - Clínica y LaboratorioDocument8 pagesAR - Clínica y LaboratoriomonseibanezbarraganNo ratings yet

- Gout & PseudogoutDocument14 pagesGout & PseudogoutPatrick CommettantNo ratings yet

- Clinical Features of Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument5 pagesClinical Features of Rheumatoid ArthritisGW GeistNo ratings yet

- Acutely Swollen JointDocument7 pagesAcutely Swollen JointHossein VakiliNo ratings yet

- TB Tulang 3 PDFDocument6 pagesTB Tulang 3 PDFkeysmeraudjeNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument29 pagesRheumatoid ArthritisvijitajayaminiNo ratings yet

- VasculitidesDocument44 pagesVasculitidesNikki LumidaoNo ratings yet

- Seronegatice ArthritisDocument23 pagesSeronegatice ArthritissamreignsNo ratings yet

- Spondyloarthropathies: Reactive Arthritis (Reiter's Syndrome)Document6 pagesSpondyloarthropathies: Reactive Arthritis (Reiter's Syndrome)Regine Benedicte VidalNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Presented By: Layan S. Barqawi Supervisor: Dr. Dirar DibsDocument10 pagesRheumatoid Arthritis: Presented By: Layan S. Barqawi Supervisor: Dr. Dirar Dibsasop06No ratings yet

- Reumatoid ArthritisDocument19 pagesReumatoid Arthritishenning_mastereid166No ratings yet

- Gout and Hyperuricemia: A Peer-Reviewed Bulletin For The Family PhysicianDocument6 pagesGout and Hyperuricemia: A Peer-Reviewed Bulletin For The Family PhysicianRhoda LicardoNo ratings yet

- GoutDocument10 pagesGoutAmberNo ratings yet

- Faculty of MedicineDocument28 pagesFaculty of MedicineRana AtefNo ratings yet

- Presentation - JointsDocument21 pagesPresentation - JointsAlejandra MorenoNo ratings yet

- Enteropathic Arthritis by Balamurali Krishna Muralee Dharan VeenaDocument26 pagesEnteropathic Arthritis by Balamurali Krishna Muralee Dharan VeenaBala Murali KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Inflamed Joint: The Right Clinical Information, Right Where It's NeededDocument51 pagesAssessment of Inflamed Joint: The Right Clinical Information, Right Where It's NeededLucía ElisaNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid Arthritis StudentDocument10 pagesRheumatoid Arthritis StudentFay La CruzNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument8 pagesRheumatoid Arthritisjronney56No ratings yet

- Name: ID:: Madiha Sayed Nagy. 51859Document12 pagesName: ID:: Madiha Sayed Nagy. 51859drng48No ratings yet

- Diagnosing Acute Monoarthritis in Adults PDFDocument8 pagesDiagnosing Acute Monoarthritis in Adults PDF蔡季霖No ratings yet

- 11th May MRCP RecallsDocument2,080 pages11th May MRCP Recallsgirlygirl10No ratings yet

- Assesment GODocument17 pagesAssesment GOBHUENDOCRINE SRNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid Arthritis: Anthony SafiDocument9 pagesRheumatoid Arthritis: Anthony SafiAnthony safiNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Ultrasound in Identifying and Differeniating Patients With Early ArthritisDocument10 pagesThe Importance of Ultrasound in Identifying and Differeniating Patients With Early ArthritisLarissa RodNo ratings yet

- Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis of OsteoarthritisDocument25 pagesClinical Manifestations and Diagnosis of OsteoarthritisjaquimqNo ratings yet

- Acute Rheumatic Fever - Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument15 pagesAcute Rheumatic Fever - Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis - UpToDateDannyGutierrezNo ratings yet

- Review On Treatment of Gout & HyperuricemiaDocument11 pagesReview On Treatment of Gout & HyperuricemiaMirza ProthikhaNo ratings yet

- RheumatoidDocument26 pagesRheumatoidArja' WaasNo ratings yet

- Charcot Foot in DiabetesDocument9 pagesCharcot Foot in DiabetesAlma EscamillaNo ratings yet

- Gout&Pseudogout UpdateDocument54 pagesGout&Pseudogout UpdateSandy AgustianNo ratings yet

- Inflammatory AtritisDocument17 pagesInflammatory Atritiskumoro panjiNo ratings yet

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument16 pagesRheumatoid Arthritisbudak46No ratings yet

- ArthritisDocument8 pagesArthritissdorji72No ratings yet

- RematikDocument66 pagesRematikYolla LitaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Patient With Joint DiseaseDocument14 pagesEvaluation of The Patient With Joint Diseaseqayyum consultantfpscNo ratings yet

- Osteoarthritis: OsteoartriteDocument9 pagesOsteoarthritis: OsteoartriteSofia Cerezo MuñozNo ratings yet

- Hands On: The Approach To The Patient Presenting With Multiple Joint PainDocument12 pagesHands On: The Approach To The Patient Presenting With Multiple Joint PainMithun CbNo ratings yet

- Penyakit GoutDocument34 pagesPenyakit Goutluh komang ari trisna jayantiNo ratings yet

- Artritis ReumatoideDocument5 pagesArtritis Reumatoiderachel100% (1)

- Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument23 pagesRheumatoid Arthritisfabunmiopeyemiv23No ratings yet

- PR Dr. ArinaDocument3 pagesPR Dr. ArinaHanihafezah ShafiiNo ratings yet

- POTT's DiseaseDocument3 pagesPOTT's DiseaseFema Jill AtrejenioNo ratings yet

- Gout Term PaperDocument8 pagesGout Term Paperafmzubkeaydllz100% (1)

- Case Scenario Nursing ProcessDocument4 pagesCase Scenario Nursing ProcessJOANNA MAE ABIA SALOMONNo ratings yet

- Nitesh Kumar Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument8 pagesNitesh Kumar Rheumatoid Arthritisnitesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Hand Conditions and Examinations: a Rheumatologic and Orthopaedic ApproachFrom EverandHand Conditions and Examinations: a Rheumatologic and Orthopaedic ApproachNo ratings yet

- OJC Vol 31 (2) p1181-1184Document4 pagesOJC Vol 31 (2) p1181-1184Suryo HardjoNo ratings yet

- MSG - Konsensus 2008Document6 pagesMSG - Konsensus 2008Suryo HardjoNo ratings yet

- Dbil RatioDocument11 pagesDbil RatioSuryo HardjoNo ratings yet

- 5 Ammonia Predicts Poor Outcomes in Patients Withhepatitis B Virus-Related Acute On Chronic Liver FailuDocument6 pages5 Ammonia Predicts Poor Outcomes in Patients Withhepatitis B Virus-Related Acute On Chronic Liver FailuSuryo HardjoNo ratings yet

- ALTERNI Newsletter (Issue3)Document30 pagesALTERNI Newsletter (Issue3)pohlevoonNo ratings yet

- Gout Guide: Lifelong Transformation, One Healthy Habit at A Time®Document9 pagesGout Guide: Lifelong Transformation, One Healthy Habit at A Time®Rocco McWhitebeardNo ratings yet

- Synovial FluidDocument8 pagesSynovial FluidMary ChristelleNo ratings yet

- NaicineDocument9 pagesNaicineKitz Tanael100% (1)

- Guide To HerbsDocument10 pagesGuide To Herbsgbodhi100% (2)

- LOW PURINE and Your DietDocument4 pagesLOW PURINE and Your DietAnna ReyesNo ratings yet

- Block H FinalDocument16 pagesBlock H FinalF ParikhNo ratings yet

- Verga - Jasmine Activity 1 CHN RleDocument16 pagesVerga - Jasmine Activity 1 CHN RleJASMINE VERGANo ratings yet

- Medical-Surgical Nursing 3Document2 pagesMedical-Surgical Nursing 3Charissa Magistrado De LeonNo ratings yet

- Common Causes of Severe Knee PainDocument8 pagesCommon Causes of Severe Knee PainRatnaPrasadNalamNo ratings yet

- Upgraded Muskuloskeletal DisordersDocument6 pagesUpgraded Muskuloskeletal DisordersArvinjohn GacutanNo ratings yet

- Asymptomatic HyperuricemiaDocument46 pagesAsymptomatic HyperuricemiaDivya Shree100% (1)

- Artritis Gout in Aviation MedicineDocument22 pagesArtritis Gout in Aviation MedicineBuyungNo ratings yet

- SK 5. OADocument36 pagesSK 5. OApitinoveNo ratings yet

- Vikash Homeo Research Compile Book For Homeopath To Promote Homeopath For AllDocument1,384 pagesVikash Homeo Research Compile Book For Homeopath To Promote Homeopath For AllvijaykakraNo ratings yet

- GOUT Case StudyDocument3 pagesGOUT Case StudySunshine_Bacla_42750% (1)

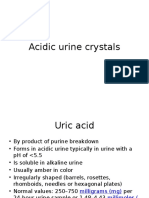

- Acidic Urine CrystalsDocument11 pagesAcidic Urine CrystalsAdriana GarciaNo ratings yet

- Febuxostat in GoutDocument7 pagesFebuxostat in GoutLia NadaNo ratings yet

- AllopurinolDocument7 pagesAllopurinolSahera Nurhidayah NasutionNo ratings yet

- Pathomorphology Final ExamDocument262 pagesPathomorphology Final ExamMann SarwanNo ratings yet

- ICU Guide OneDocument318 pagesICU Guide OneSamar DakkakNo ratings yet

- ArthritisDocument15 pagesArthritisPrambudi KusumaNo ratings yet

- 12.musculoskeletal System 4 Blocks Eduwaves360Document729 pages12.musculoskeletal System 4 Blocks Eduwaves360ÇağlaNo ratings yet

- Kangen Water For EveryoneDocument71 pagesKangen Water For EveryoneRudyard83% (6)

- Gouty ArthritisDocument12 pagesGouty ArthritisManoj KandoiNo ratings yet

- Blood Fluid Examination StrasingerDocument4 pagesBlood Fluid Examination StrasingerChristin SchlittNo ratings yet

- Brainstorming-Emerald SeasonDocument11 pagesBrainstorming-Emerald SeasonHaydi Pineda MedinaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Inflammatory Diet_ Anti-Inflammatory Diet Box Set_ Anti-Inflammatory Diet Cookbook, Anti-Inflammatory Recipes, Anti-Inflammatory Plan_ Anti-Inflammatory ... Recipes, Anti-Inflammatory Plan) ( PDFDrive )Document817 pagesAnti-Inflammatory Diet_ Anti-Inflammatory Diet Box Set_ Anti-Inflammatory Diet Cookbook, Anti-Inflammatory Recipes, Anti-Inflammatory Plan_ Anti-Inflammatory ... Recipes, Anti-Inflammatory Plan) ( PDFDrive )Suica Ana Maria100% (1)