Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/41 May/June 2018

Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/41 May/June 2018

Uploaded by

malisaandileOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/41 May/June 2018

Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/41 May/June 2018

Uploaded by

malisaandileCopyright:

Available Formats

Cambridge Assessment International Education

Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced Level

HISTORY 9389/41

Paper 4 Depth Study May/June 2018

MARK SCHEME

Maximum Mark: 60

Published

This mark scheme is published as an aid to teachers and candidates, to indicate the requirements of

the examination. It shows the basis on which Examiners were instructed to award marks. It does not

indicate the details of the discussions that took place at an Examiners’ meeting before marking began,

which would have considered the acceptability of alternative answers.

Mark schemes should be read in conjunction with the question paper and the Principal Examiner

Report for Teachers.

Cambridge International will not enter into discussions about these mark schemes.

Cambridge International is publishing the mark schemes for the May/June 2018 series for most

Cambridge IGCSE™, Cambridge International A and AS Level and Cambridge Pre-U components,

and some Cambridge O Level components.

IGCSE™ is a registered trademark.

This document consists of 15 printed pages.

© UCLES 2018 [Turn over

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Generic Marking Principles

These general marking principles must be applied by all examiners when marking candidate answers. They should be applied alongside the

specific content of the mark scheme or generic level descriptors for a question. Each question paper and mark scheme will also comply with these

marking principles.

GENERIC MARKING PRINCIPLE 1:

Marks must be awarded in line with:

• the specific content of the mark scheme or the generic level descriptors for the question

• the specific skills defined in the mark scheme or in the generic level descriptors for the question

• the standard of response required by a candidate as exemplified by the standardisation scripts.

GENERIC MARKING PRINCIPLE 2:

Marks awarded are always whole marks (not half marks, or other fractions).

GENERIC MARKING PRINCIPLE 3:

Marks must be awarded positively:

• marks are awarded for correct/valid answers, as defined in the mark scheme. However, credit is given for valid answers which go beyond the

scope of the syllabus and mark scheme, referring to your Team Leader as appropriate

• marks are awarded when candidates clearly demonstrate what they know and can do

• marks are not deducted for errors

• marks are not deducted for omissions

• answers should only be judged on the quality of spelling, punctuation and grammar when these features are specifically assessed by the

question as indicated by the mark scheme. The meaning, however, should be unambiguous.

GENERIC MARKING PRINCIPLE 4:

Rules must be applied consistently e.g. in situations where candidates have not followed instructions or in the application of generic level

descriptors.

© UCLES 2018 Page 2 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

GENERIC MARKING PRINCIPLE 5:

Marks should be awarded using the full range of marks defined in the mark scheme for the question (however; the use of the full mark range may

be limited according to the quality of the candidate responses seen).

GENERIC MARKING PRINCIPLE 6:

Marks awarded are based solely on the requirements as defined in the mark scheme. Marks should not be awarded with grade thresholds or

grade descriptors in mind.

© UCLES 2018 Page 3 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question

Generic Levels of Response Marks

1–12

Level 5 Responses show a very good understanding of the question and contain a relevant, focused and balanced argument, fully 25–30

supported by appropriate factual material and based on a consistently analytical approach.

Towards the top of the level, responses may be expected to be analytical, focused and balanced throughout. The candidate

will be in full control of the argument and will reach a supported judgement in response to the question.

Towards the lower end of the level, responses might typically be analytical, consistent and balanced but the argument might

not be fully convincing.

Level 4 Responses show a good understanding of the question and contain a relevant argument based on a largely analytical 19–24

approach.

Towards the top of the level, responses are likely to be analytical, balanced and effectively supported. There may be some

attempt to reach a judgement but this may be partial or unsupported.

Towards the lower end of the level, responses are likely to contain detailed and accurate factual material with some focused

analysis but the argument is inconsistent or unbalanced.

Level 3 Responses show understanding of the question and contain appropriate factual material. The material may lack depth. Some 13–18

analytical points may be made but these may not be highly developed or consistently supported.

Towards the top of the level, responses contain detailed and accurate factual material. However, attempts to argue relevantly

are implicit or confined to introductions or conclusions. Alternatively, responses may offer an analytical approach which

contains some supporting material.

Towards the lower end of the level, responses might offer narrative or description relating to the topic but are less likely to

address the terms of the question.

© UCLES 2018 Page 4 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question

Generic Levels of Response Marks

1–12

Level 2 Responses show some understanding of the demands of the question. They may be descriptive with few links to the question 7–12

or may be analytical with limited relevant factual support.

Towards the top of the level, responses might contain relevant commentaries which lack adequate factual support. The

responses may contain some unsupported assertions.

Towards the lower end of the level, responses are likely to contain some information which is relevant to the topic but may

only offer partial coverage.

Level 1 Responses show limited understanding of the question. They may contain some description which is linked to the topic or only 1–6

address part of the question.

Towards the top of the level, responses show some awareness of relevant material but this may be presented as a list.

Towards the lower end of the level, answers may provide a little relevant material but are likely to be characterised by

irrelevance.

Level 0 No relevant creditworthy content. 0

© UCLES 2018 Page 5 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

1 To what extent were Lenin’s policies determined by necessity rather than by ideology? 30

The focus of the response should lie on the motivation behind the policies that Lenin followed in the years of his domination of

Russia’s politics. There should be evidence also of the basic tenets of Lenin’s ideology. While there is no expectation that

there should be mention of his policies before 1918, credit should be given, for example, for the promise of ‘Land’ after the

April Theses, which arguably was designed to appeal to an alienated peasantry and conflicted with Marxist principles of state

ownership and a command economy. There are many examples where necessity was the dominant influence and ideology

was relegated, for the short term at least. The decision to close the Constituent Assembly, the savage terms of Brest Litovsk,

many of the methods of waging war during the Civil War, the crushing of the Kronstadt sailors, aspects of War Communism

and above all the NEP could be considered. There was also the re-hiring of Tsarist officers and former managers. All of those

could be seen as decidedly ‘Un-Marxist’. However, there are many examples which could be seen as a case ‘for’. The

fundamental idea behind War Communism was a command economy: the needs of the state were paramount. The NEP was

seen as a temporary measure, as were the concessions of Brest Litovsk. Structures were being set up to ensure the state

controlled the economy and there was centralised planning. Moves were made to spread the revolution abroad with the

creation of the Comintern. The first steps were taken to move towards equality and eliminate class barriers. Certainly, under

Lenin the goal was a Marxist state, even if the Marxist part had to be modified slightly to deal with the circumstances that

Russia found itself in, in the early 1920s.

2 To what extent can the rise of Fascism in Italy be attributed to the fear of communism? 30

What is looked for here is a debate and an answer to the question of what factors led to the rise of fascism in Italy. The role of

a fear of communism needs to be balanced against a range of other factors, several of which could be seen to be of greater

importance. The topic is a much debated one with no consensus amongst the experts. Certainly, this fear did play a part

amongst many. It was central to the attitude of both the Pope and many of the Catholic hierarchy. It was important to many of

the northern industrialists as well as large landowners in the south. It was also a factor in influencing the neutral attitude of

some of the senior military as well as some parts of the press and the middle classes. There was a lot of industrial unrest. It

was also a factor in the King’s thinking. However, some have argued that more important was the way it was utilised and that

it was not a serious threat at all. Clearly here were a wide range of other factors which could be considered. Mussolini himself

had considerable talent as a speaker and writer, and his ability to adapt his policies and actions to the circumstances of the

time, as well as gamble, stood him in good stead. There was the disastrous legacy of the war and the deep sense of

disillusion which followed it. There was social unrest and economic chaos and few politicians around seemed to have the

ability to deal with it. Democracy was a comparatively new arrival in Italy, and there were elites who actively undermined it.

The Liberal governments had produced few leaders of quality and the electoral system tended to reflect the political instability

inherent in Italy at the time.

© UCLES 2018 Page 6 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

3 How far did Stalin modernise the Soviet economy? 30

There needs to be reflection or a definition of what ‘modernisation’ might mean in this context in order to set out a balanced

argument. In one sense, he did move Russia in a forward direction in that he eliminated the last vestiges of the old regime

and aimed, at least in theory, at a classless society based on merit. If modernisation is seen as the creation of a

military/industrial state, then that did happen. If modernisation is seen as the creation of heavy industry, then this happened

as well as the emergence of new industries and their capacity to support a vast army when needed. How the state itself was

structured could be debated at length; a full command economy was not necessarily ‘modern’, although it was different from

the previous experience. What happened in agriculture again could be debated, as while the intention may have been to

‘modernise’, the result was a disaster. In social terms, there is definitely a case ‘for’ with ideas of equality for women,

healthcare for all, educational provision and careers open to talent. Again, the reality was sometimes disappointing but, in

many cases, there was real progress. Thousands of tractors were produced but, in many cases, no one had thought of the

need to provide fuel for them or any spare parts. Quantity, meeting the ‘norm’, was all important; quality often was not.

4 ‘The main reason why Hitler faced so little opposition was because he brought real benefits to the German people.’ 30

How far do you agree?

Some may wish to debate the ‘so little’ aspect of the question, but it is generally accepted that this was in fact the case. There

is scope for ample debate on the issue and also a case for arguing that the reasons changed as the ’30s progressed. For

many Germans, there were genuine benefits in that unemployment dropped rapidly, the fear of communism had gone, re-

armament saw industrialists’ profits rise, the army got its benefits in terms of expansion (and the SA leadership killed!) and the

humiliation felt as a result of Versailles started to go. Quite how ‘real’ these benefits were is something that can be debated as

the foundations on which the economy was based were flawed. However, there are a variety of other factors which could be

considered. There was an effective system of terror with the Gestapo and the SS, and the police and the judiciary were

almost totally compliant with the wishes of the regime. There was an effective propaganda and indoctrination programme and

there were many memories of what had happened to show the failings of the Weimar Republic. The fact that Hitler had come

to power ‘legitimately’ by election and formal endorsement by Hindenburg was important also. There was no real tradition of a

‘loyal’, or legitimate, opposition in German politics; the tendency was to support established authority, and Hitler had taken

great care to look properly ‘established’.

© UCLES 2018 Page 7 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

5 Assess the causes and consequences of the ‘move to the suburbs’ in the 1950s. 30

The suburbs can be defined as areas of low-density housing close to but away from the downtown city centres. In the 1950s,

many Americans moved from cities to the suburbs. How many moved is hard to say as some of the growth in suburban

population occurred in the suburbs rather than people moving there.

Causes of the move from city to suburbs in the 1950s include:

• Federal subsidy of mortgages for those who had fought in the war, via the G.I. Bill.

• ‘White flight’. As African Americans moved from the South to Northern cities, so whites moved to the suburbs, where

many estates had restrictions on who could live there.

• The growth of the automobile society, which enabled commuting to work. Linked with this was the building of

interstate highways from the mid-1950s.

• The availability of cheap, mass-produced homes, known as Levitt towns.

The effects of the move to the suburbs are harder to pin down. They could include:

• The continuation of the ‘baby boom’ into the later 1950s and early 1960s.

• The growth of a suburban way of life around strip malls and drive-in cinemas.

• The growth of commuting to work by car over long distances.

• The social isolation of many suburban families, most of them young and nuclear, with mother staying at home to look

after the children. Betty Friedan criticised this aspect of US life in her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. Whether

she was right to do so is more arguable.

© UCLES 2018 Page 8 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

6 ‘Attempts in the 1960s and 1970s to improve their lives proved short-lived and unsuccessful.’ How accurate is this 30

statement with regard to either Hispanics or Native Americans?

For Hispanics, the main attempt to improve their lives focuses on the efforts of Cesar Chavez and the farm workers of

California. For Native Americans, efforts were led by the American Indian Movement (AIM). The lives of both groups had been

impoverished for many decades; by the 1960s, Native Americans were the poorest minority group, with an average life

expectancy of 44 years.

Hispanics

• Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta organised some Hispanic farm workers into a labour union – the United Farm

Workers (UFW) – and helped lead the Delano Grape Strike, which lasted from 1965 to 1970. Another dispute was

the Salad Bowl strike of 1970–71.

• The strike caused nationwide boycotts of Californian grapes, which forced some concessions from grape growers,

e.g. union recognition and contracts for farm workers rather than casual labour.

• However, by the late 1970s, the labour movement was divided over tactics and strategy, thus losing impact and

support. For Hispanics in industrial work and living in cities, little was done.

Native Americans

• The American Indian Movement (AIM), part of what some call the Red Power movement of the 1960s, made an

impact when in 1969 it took control of Alcatraz, the former federal prison, for 19 months.

• This action encouraged further protests and acts of civil disobedience by Native Americans across the USA,

including Washington DC and the site of the massacre at Wounded Knee.

• These protests gained some support from white liberals, e.g. Marlon Brando and his protest at the 1973 Oscar

awards.

• Native Americans did make some legislative gains, especially in terms of education and healthcare.

• The judiciary, including the US Supreme Court, also made judgements in their favour, e.g. over hunting and fishing

rights.

• AIM remained active from the 1970s to the present but its impact diminished, at least at the national level.

© UCLES 2018 Page 9 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

7 ‘The rise of the New Right in the 1980s was sudden in speed and dramatic in impact.’ How far do you agree? 30

The New Right was in marked contrast to the Old Right, which was moderate and centrist in its views, willing to compromise

with liberal Democrats. It marked the end of the post-war consensus on government policies and priorities. The New Right

was more ideological, being anti-federal government, anti-liberal and socially and economically conservative. The first sign of

the New Right was the campaign of Barry Goldwater in 1964 and he was soundly beaten by LBJ. Sixteen years later and the

New Right led the election of Ronald Reagan as President. Democratic liberals were out of power. The 1980 election result

marked the rise of the New Right; Reagan’s presidency was the impact of that rise.

Arguments that the rise of the New Right was sudden revolve around analysis of the 1980 election.

• Previous presidencies, including Nixon’s and Ford’s, had followed the post-war consensus. Carter had done his best

to do so but stagflation showed the failure of that model. If the rise of the New Right is dated as the response of the

Right to the failure of the Carter presidency, then that rise was sudden. If it is linked back to Goldwater, then it was

not.

Arguments that the rise of the New Right was impactful revolve around analysis of the Reagan presidency and especially its

first term.

• The New Right’s domestic priority was curbing inflation – via monetarism and high interest rates – rather than

ensuring full employment via fiscal policy. This had major consequences for the US economy in the early 1980s.

• The New Right’s social policy goals were harder to achieve, e.g. reducing abortion rights, because of checks and

balances of the US constitution.

• In terms of foreign policy, the New Right called themselves Neo-conservatives, taking a much tougher line against

the USSR, e.g. Reagan’s ‘evil empire’ speech.

© UCLES 2018 Page 10 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

8 How successful was US policy towards Cuba in the period from 1956 to 1963? 30

In 1959, the right-wing Batista dictatorship of Cuba was replaced by the left-wing party dictatorship of Castro. Two years later,

Eisenhower was replaced by Kennedy as US President. The USA had always had a special relationship with Cuba, just 90

miles off the Florida coast, and often seen as being America’s backyard.

There were perhaps four main stages in US policy towards Cuba in these years:

• 1956–58: traditional support for right-wing government of Batista, even though a dictatorship.

• 1958–59: neutrality in the civil war between Batista and Castro. In 1958, the USA imposed an arms embargo on

Cuba, which benefited Castro more than Batista.

• 1959–60: initial acceptance of the Castro regime. The USA recognised the Castro regime. Castro even visited the

USA, though he did not meet Eisenhower.

• 1960–62: growing hostility as Cuba began to nationalise foreign companies, many of them American, and the USA

imposed a trade embargo on Cuba. This pushed Cuba towards the USSR.

Fear of a Communist Cuba and its effect on the region led to plans to topple Castro, as shown by the CIA-organised Bay of

Pigs attack in April 1961. The CIA continued to plan to overthrow Castro, even after the Cuban missile crisis.

The better responses will identify criteria for measuring success, which should focus on the aims of the USA. The outcome of

the Cuban missile crisis might be seen as the main success of US policy towards Cuba in that it stopped Cuba from

becoming a Soviet base in America’s backyard.

© UCLES 2018 Page 11 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

9 Which of the two superpowers was more responsible for causing the globalisation of the Cold War in the period from 30

1950 to 1975?

USSR – Stalin had openly spoken of a worldwide communist revolution, and the USSR supported pro-communist groups in

Latin America, Africa and the Middle East. Although Khrushchev spoke of ‘peaceful coexistence’, he still believed that

communism would spread worldwide and was willing to support what he saw as vulnerable communist states, such as Cuba.

The USSR provided military support to communist forces in both Korea and Vietnam, and Stalin was at least implicitly

involved in the invasion of South Korea by North Korea. The creation of many new, vulnerable and unstable states which

occurred as a result of decolonisation provided an opportunity for the USSR to spread its influence, prestige and power.

USA – The USA saw communism as a threat to the free market economy on which it depended for its trade and economic

prosperity. The fall of China to communism in 1949 convinced the USA that there was a plot, orchestrated by the USSR, to

spread communism globally. The USA therefore adopted the policy of containment (and, at times, roll back) to prevent this.

Convinced that Stalin was behind North Korea’s invasion of the South, the USA became involved in what was essentially a

regional, nationalistic war, thus globalising the Cold War. Concerned about the ‘domino effect’, the USA also became involved

in Vietnam, Cambodia, etc., thereby spreading the Cold War to SE Asia. With the same aim of preventing the spread of

communism, the USA became involved in Latin America (e.g. Chile, Guatemala, Brazil, Nicaragua), Africa (e.g. Ghana,

Congo) and the Middle East (fearing that the USSR was trying to gain influence in the region, thereby threatening American

oil supplies). The USA misinterpreted the extent of the USSR’s involvement in these events and, in over-reacting, spread the

Cold War globally.

© UCLES 2018 Page 12 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

10 ‘The person who deserves most of the credit for ending the Cold War is Mikhail Gorbachev.’ How far do you agree? 30

When Gorbachev became its leader in 1985, the USSR was suffering from economic and political stagnation. A succession of

old and infirm leaders following Brezhnev’s death in 1982 (Andropov, Chernenko – the gerontocracy) had led to inertia, while

there were increasing calls for political reform in Eastern Europe. Gorbachev saw the need to make the USSR more

productive and economically viable; this could only be achieved by reducing military expenditure and spending on supporting

communist governments throughout the world. Gorbachev’s New Political Thinking led to domestic reform (perestroika,

glasnost, democratisation) and a willingness to negotiate with the West. Gorbachev ended the Brezhnev Doctrine, partly to

reduce expenditure and partly because he believed that the best way to rejuvenate communism was to introduce a degree of

liberalism. As a result, the USSR effectively gave up control of Eastern Europe. Reagan and Thatcher hailed Gorbachev as a

man with whom they could ‘do business’. Negotiations between Reagan and Gorbachev at a series of summit meetings led to

their joint declaration that the Cold War was over (Malta 1989).

Given the parlous state of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev had little option but to attempt reform in the USSR and seek

negotiations with the West. In addition to the USSR’s dire economic and political situation, Gorbachev faced enormous

pressure from the USA. Reagan’s policy of militarised counter-revolution demonstrated the USA’s determination to pursue the

Second Cold War on all fronts. He vastly increased defence expenditure (13% in 1982; 8% in 1983; 8% in 1984). New

methods of deploying nuclear missiles were developed (e.g. Stealth Bomber, Trident submarines). His development of SDI

was so costly that the USSR would simply not be able to match American expenditure. Under the Reagan Doctrine, the USA

sent assistance to anti-communist insurgents and governments, with the aim of reducing the USSR’s influence in the Third

World (e.g. supporting the Contras in Nicaragua; supporting the right-wing government of El Salvador). The USA used radio

broadcasts to encourage anti-communist sentiments in Eastern Europe. The USA used economic sanctions against Poland

when its government banned the independent trade union Solidarity. Thatcher’s Britain supported Reagan’s hard line against

the ‘evil empire’; by allowing US nuclear missile bases in Britain, she was imposing further pressure on the USSR. Unable to

match the USA’s military expenditure, Gorbachev had no choice but to call an end to the arms race and the Cold War. With

the pressure which his policies imposed on the USSR clearly working, Reagan was prepared to negotiate with Gorbachev

from a position of strength.

© UCLES 2018 Page 13 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

11 ‘A strategy for identifying and dealing with dissidents.’ How far do you agree with this assessment of the Hundred 30

Flowers Campaign?

Historians disagree over Mao’s motives for starting the Hundred Flowers Campaign. Some argue that the campaign stemmed

from an error of judgement on Mao’s part, while others suggest that it was a deliberate plan to identify and deal with

dissidents.

It could be argued that, from its inception in 1956, the campaign was a plan to expose Rightists, counter-revolutionaries and

those who posed a threat to the government. The campaign encouraged constructive criticism of the government’s communist

policies, and Mao gave assurances that contributors would not be punished. Yet, in the summer of 1957, Mao began an Anti-

Rightist movement, effectively a purge of those who posed a threat to the government’s control. Between 300 000 and

550 000 people were identified as Rightists, most of them intellectuals, academics, writers and artists. They were publicly

discredited, lost their jobs and some were sent to labour camps. As a result, it discouraged dissent and made intellectuals

less willing to openly criticise Mao and his government in the future. Mao himself implied that the campaign had deliberately

set out to identify and deal with dissidents, claiming that he had ‘enticed the snakes out of their caves’.

It could be argued that this claim was merely to save face after his plan to allow open and constructive criticism had backfired.

Mao’s aim was to promote socialism and improve relations between the Party cadres, intellectuals and the new group of

technicians which had emerged from the industrial changes encouraged by the Five-Year Plan which began in 1953. He was

convinced that open discussion would clearly confirm that the government was right to see socialism as the way forward for

China. He was surprised, therefore, when both the Communist Party and he personally were so heavily criticised. The extent

and nature of this criticism were all the more concerning because Mao had witnessed Khrushchev’s speech denouncing Stalin

and the uprising in Hungary. It was only then that Mao reversed course, and began taking action against dissidents.

© UCLES 2018 Page 14 of 15

9389/41 Cambridge International AS/A Level – Mark Scheme May/June 2018

PUBLISHED

Question Answer Marks

12 To what extent was Israel’s victory in the Six Day War the result of its superior air power? 30

Superior air power enabled Israel to launch a pre-emptive attack against the Arab forces. A series of devastating air strikes

destroyed most of the Egyptian air force on the ground. This guaranteed that Israel had control of the air, thus enabling it to

move its ground troops quickly and effectively behind the air strikes. Israeli troops were therefore able to take the Gaza Strip

and the whole of Sinai from Egypt, the rest of Jerusalem and the West Bank from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria.

The speed with which this was accomplished was largely due to the effectiveness of Israeli air strikes, made possible by

Israel’s possession of modern and well equipped aircraft.

Israel had been given plenty of warning about an impending Arab attack. The Arab states had refused to sign a treaty at the

end of the 1948–49 war and were still refusing to formally recognise the state of Israel. President Aref of Iraq had openly

stated ‘our goal is to wipe Israel off the map’, while Syria had started to bombard Jewish settlements from the Golan Heights.

President Nasser of Egypt had requested the removal of the UN peacekeeping force from Egyptian territory and closed the

Gulf of Aqaba. Egyptian, Syrian, Jordanian, Lebanese, Iraqi, Saudi Arabian and Algerian troops had begun to mass along the

Israeli border. The Israeli belief that the Arab intention was to attack Israel enabled the Israelis time to prepare their own

plans. Moreover, Arab confidence had been boosted by the assumption that they would receive support from the Soviet

Union; in the event, such support was not forthcoming. The main reason for Israel’s success, therefore, was the slow and very

obvious preparations for war made by the combined Arab forces.

© UCLES 2018 Page 15 of 15

You might also like

- Key FIM302cDocument63 pagesKey FIM302cNguyen Thi Thu Huong (K16HL)No ratings yet

- AP® Macroeconomics Crash Course, For the 2021 Exam, Book + Online: Get a Higher Score in Less TimeFrom EverandAP® Macroeconomics Crash Course, For the 2021 Exam, Book + Online: Get a Higher Score in Less TimeNo ratings yet

- Gyn MCQs PRIMEsDocument40 pagesGyn MCQs PRIMEssk100% (2)

- 9389 w18 Ms 42Document24 pages9389 w18 Ms 42HarisNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Examinations: History 9389/43 May/June 2017Document18 pagesCambridge International Examinations: History 9389/43 May/June 2017malisaandileNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/41 May/June 2020Document21 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/41 May/June 2020Vasia PapageorgiouNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Examinations: History 9389/41 May/June 2017Document20 pagesCambridge International Examinations: History 9389/41 May/June 2017malisaandileNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/23 October/November 2018Document26 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/23 October/November 2018Alina WasimNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International Examinations: History 9389/42 May/June 2017Document20 pagesCambridge International Examinations: History 9389/42 May/June 2017malisaandileNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/42 May/June 2020Document19 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/42 May/June 2020krystellNo ratings yet

- Revolutionary 60s and 70s QuestionDocument15 pagesRevolutionary 60s and 70s QuestionMaider SerranoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/33 May/June 2018Document7 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/33 May/June 2018btsadziwaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/23 October/November 2020Document18 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/23 October/November 2020SylvainNo ratings yet

- Olevels Past PaperDocument14 pagesOlevels Past PaperAlisha SmithNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/23 May/June 2019Document29 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/23 May/June 2019Sibo ZhaoNo ratings yet

- Answer Script 9739 Summer of 2019Document28 pagesAnswer Script 9739 Summer of 2019saad waheedNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/12 October/November 2018Document13 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/12 October/November 2018Bryan TicharwaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/31 October/November 2018Document18 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/31 October/November 2018Yeager MahunzeNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/12 May/June 2018Document12 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/12 May/June 2018Alexa AnghelNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/32 October/November 2018Document18 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/32 October/November 2018shwetarameshiyer7No ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/42 May/June 2018Document11 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/42 May/June 2018Kudakwashe TakawiraNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/22 May/June 2018Document13 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/22 May/June 2018TheSpooky GhostツNo ratings yet

- 2058 s18 Ms 12Document15 pages2058 s18 Ms 12Bashir GulNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/21 May/June 2019Document13 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/21 May/June 2019Hamna SialNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/31 May/June 2018Document18 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/31 May/June 2018Yeager MahunzeNo ratings yet

- A Levels Marking Guide Paper 3Document8 pagesA Levels Marking Guide Paper 3Damian Dze Aja SuhNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Islamic Studies 2068/12 October/November 2018Document15 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Islamic Studies 2068/12 October/November 2018zmunawwirNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/23 October/November 2022Document24 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/23 October/November 2022Tomisin KoladeNo ratings yet

- 9389 s19 Ms 33Document7 pages9389 s19 Ms 33zefridNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/12 May/June 2019Document16 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 9389/12 May/June 2019Sibo ZhaoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Global Perspectives and Research 9239/12 May/June 2018Document11 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Global Perspectives and Research 9239/12 May/June 2018Adelina ANo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Global Persectives 0457/11 October/November 2018Document13 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Global Persectives 0457/11 October/November 2018Pooja GodfreyNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/23 May/June 2022Document18 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/23 May/June 2022Tomisin KoladeNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/32 May/June 2018Document18 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/32 May/June 2018Yeager MahunzeNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/31 May/June 2020Document7 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/31 May/June 2020chenjy38No ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/42Document16 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/42humpho45No ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: This Document Consists of 14 Printed PagesDocument14 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: This Document Consists of 14 Printed PagesMuhammadNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 March 2018Document92 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 March 2018Rhea AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: This Document Consists of 15 Printed PagesDocument15 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: This Document Consists of 15 Printed PagesAli ShimlanNo ratings yet

- 03 9708 42 Ms Final Rma 22032024Document18 pages03 9708 42 Ms Final Rma 22032024eco2dayNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/21 May/June 2022Document17 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/21 May/June 2022Michael Rice SitholeNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/22 October/November 2022Document23 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/22 October/November 2022Tomisin KoladeNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/32Document7 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/32chemceptualwithfaizNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/33 October/November 2020Document7 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/33 October/November 2020stephNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/21 May/June 2020Document20 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/21 May/June 2020dxD.T.C.dxNo ratings yet

- June 2021 Mark Scheme Paper 31Document8 pagesJune 2021 Mark Scheme Paper 31EmmaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/22Document21 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9489/22chemceptualwithfaizNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 October/November 2019Document92 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 October/November 20198dnjb4td6pNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 May/June 2019Document92 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 May/June 2019janmarkowski23No ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/42 May/June 2019Document9 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/42 May/June 2019Cristian TudoracheNo ratings yet

- 2021 Specimen Paper 3 Mark SchemeDocument8 pages2021 Specimen Paper 3 Mark SchemekeminellyNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/33 May/June 2018Document18 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Sociology 9699/33 May/June 2018Yeager MahunzeNo ratings yet

- 0457 m18 Ms 12Document15 pages0457 m18 Ms 12sallyNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Sociology 9699/11 May/June 2022Document17 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Sociology 9699/11 May/June 2022katsandeNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: HistoryDocument19 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: HistorykrystellNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 March 2019Document92 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: History 0470/12 March 2019janmarkowski23No ratings yet

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Global Perspectives and Research 9239/02 May/June 2018Document7 pagesCambridge Assessment International Education: Global Perspectives and Research 9239/02 May/June 2018Adelina ANo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Sociology 9699/22 March 2020Document10 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Sociology 9699/22 March 2020redwanNo ratings yet

- 0627 s18 Ms 2 PDFDocument12 pages0627 s18 Ms 2 PDFreva kadgeNo ratings yet

- 03 9708 22 MS Prov Rma 23022024050650Document16 pages03 9708 22 MS Prov Rma 23022024050650eco2dayNo ratings yet

- A Levels Mark Scheme Paper 2Document17 pagesA Levels Mark Scheme Paper 2Damian Dze Aja SuhNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: Literature in English 9695/42 February/March 2022Document16 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: Literature in English 9695/42 February/March 2022tapiwadonald nyabezeNo ratings yet

- Exploring Rfid'S Use in Shipping: Prepared For Kennesaw State University's Information Technology Students and StaffDocument22 pagesExploring Rfid'S Use in Shipping: Prepared For Kennesaw State University's Information Technology Students and Staffcallaway20No ratings yet

- Philippine Wildlife Species Profile ActivityDocument1 pagePhilippine Wildlife Species Profile ActivitymicahNo ratings yet

- Officeg Corporation Time Time by Within Other The The Act Registered Time TheDocument26 pagesOfficeg Corporation Time Time by Within Other The The Act Registered Time TheNigil josephNo ratings yet

- Bank of IndiaDocument63 pagesBank of IndiaArmaan ChhaprooNo ratings yet

- LLM Advice - All You Need To Know About Statement of Purpose (SOP)Document20 pagesLLM Advice - All You Need To Know About Statement of Purpose (SOP)Seema ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Dragon Capital 200906Document38 pagesDragon Capital 200906anraidNo ratings yet

- Mauro GiulianiDocument6 pagesMauro GiulianispeardzakNo ratings yet

- Research Output of Readings in Philippine History 1Document12 pagesResearch Output of Readings in Philippine History 1Itshaaa MeeNo ratings yet

- Călin Georgescu: EducationDocument3 pagesCălin Georgescu: EducationGeorge ConstantinNo ratings yet

- How To Test SMTP Services Manually in Windows ServerDocument14 pagesHow To Test SMTP Services Manually in Windows ServerHaftamu HailuNo ratings yet

- 2.6 Acuna - Norway - NorthernLightsDocument9 pages2.6 Acuna - Norway - NorthernLightssharkzvaderzNo ratings yet

- Freeman v. Grain Processing Corp., No. 13-0723 (Iowa June 13, 2014)Document63 pagesFreeman v. Grain Processing Corp., No. 13-0723 (Iowa June 13, 2014)RHTNo ratings yet

- FA REV PRB - Prelim Exam Wit Ans Key LatestDocument13 pagesFA REV PRB - Prelim Exam Wit Ans Key LatestLuiNo ratings yet

- MTC Routes: Route StartDocument188 pagesMTC Routes: Route StartNikhil NandeeshNo ratings yet

- Winning The Easy GameDocument18 pagesWinning The Easy GameLeonardo PiovesanNo ratings yet

- Banaszynski v. United States Government - Document No. 4Document2 pagesBanaszynski v. United States Government - Document No. 4Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Drug Crimes StatisticsDocument5 pagesDrug Crimes StatisticsRituNo ratings yet

- Vote of ThanksDocument3 pagesVote of ThanksSiva Shankar75% (4)

- To Canadian Horse Defence Coalition Releases DraftDocument52 pagesTo Canadian Horse Defence Coalition Releases DraftHeather Clemenceau100% (1)

- Luigi PivaDocument2 pagesLuigi PivaLuigi PivaNo ratings yet

- St. Martin vs. LWVDocument2 pagesSt. Martin vs. LWVBaby T. Agcopra100% (5)

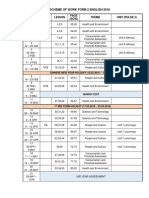

- Scheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Document2 pagesScheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Subramaniam Periannan100% (2)

- HXM ECP L2 Partner Deep Dive Sales Presentation June 2021Document103 pagesHXM ECP L2 Partner Deep Dive Sales Presentation June 2021tegara2487No ratings yet

- IA 6 Module 5-Edited-CorpuzDocument15 pagesIA 6 Module 5-Edited-CorpuzAngeline AlesnaNo ratings yet

- NV jss1Document4 pagesNV jss1Samson Oluwafemi oNo ratings yet

- Inflo Data Audit and Analysis May 2020Document37 pagesInflo Data Audit and Analysis May 2020holamundo123No ratings yet

- Spectra Precision FAST Survey User ManualDocument68 pagesSpectra Precision FAST Survey User ManualAlexis Olaf Montores CuNo ratings yet

- Mission - List Codigos Commandos 2Document3 pagesMission - List Codigos Commandos 2Cristian Andres0% (1)