Professional Documents

Culture Documents

English Language Learning Apathy - An Agender Problem in Technical Vocational Education and Training

English Language Learning Apathy - An Agender Problem in Technical Vocational Education and Training

Uploaded by

oojerinde9726Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Ebook PDF The Writers World Paragraphs and Essays With Enhanced Reading Strategies 5th Edition PDFDocument41 pagesEbook PDF The Writers World Paragraphs and Essays With Enhanced Reading Strategies 5th Edition PDFjames.lindon669100% (42)

- Literature Review-PBL and Blended LearningDocument12 pagesLiterature Review-PBL and Blended LearningBret GosselinNo ratings yet

- Language and Society-Research ProposalDocument8 pagesLanguage and Society-Research Proposalp3tru_mzq100% (2)

- Concept-Paper-U R E C S - TVL-StudentsDocument12 pagesConcept-Paper-U R E C S - TVL-Studentssinino3735No ratings yet

- Definition and Design: Aligning Language Interventions in EducationDocument16 pagesDefinition and Design: Aligning Language Interventions in EducationyutefupNo ratings yet

- EJ1297667Document13 pagesEJ1297667abaamran aylalNo ratings yet

- 472-Texto Del Artículo-2029-1-10-20160614Document26 pages472-Texto Del Artículo-2029-1-10-20160614JohnNo ratings yet

- Planning An Engaging SyllabusDocument8 pagesPlanning An Engaging SyllabusstavrosthalisNo ratings yet

- Biesta AgainstLearningDocument13 pagesBiesta AgainstLearningTina ZubovicNo ratings yet

- Bilingual Education Term PaperDocument5 pagesBilingual Education Term Paperc5rga5h2100% (1)

- EdD Assignment 3 Josephine V SalibaDocument27 pagesEdD Assignment 3 Josephine V SalibaJosephine V SalibaNo ratings yet

- Bilingual Education Thesis TopicsDocument8 pagesBilingual Education Thesis TopicsChristine Maffla100% (2)

- FinaloralmanuscrptDocument109 pagesFinaloralmanuscrptHazelBautistaNo ratings yet

- ESP Issues Article by Abdelfatteh HarrabiDocument20 pagesESP Issues Article by Abdelfatteh Harrabireem_boubakerNo ratings yet

- Empowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyDocument12 pagesEmpowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyAngely Chacón BNo ratings yet

- RESEARCHDocument29 pagesRESEARCHbugtongshana0No ratings yet

- Teaching For Learner Differences: Literature ReviewDocument17 pagesTeaching For Learner Differences: Literature Reviewfebri eka saputraNo ratings yet

- 3 Statement of The ProblemDocument17 pages3 Statement of The ProblemCharlton BrutonNo ratings yet

- Bilingualism PDFDocument13 pagesBilingualism PDFFarah MalikNo ratings yet

- Bond (2019) International Students Language Culture and The Performance of IdentityDocument18 pagesBond (2019) International Students Language Culture and The Performance of Identityspaceship9No ratings yet

- Sahibah Aguero Department of English Education, University of Syiah Kuala, IndonesiaDocument8 pagesSahibah Aguero Department of English Education, University of Syiah Kuala, IndonesiaRaziSyukriNo ratings yet

- Scaffolding in An EFL ClassroomDocument10 pagesScaffolding in An EFL ClassroomYuyun Yurnaningsih SuhendiNo ratings yet

- Food For Thought English As A Medium of Instruction Web in ArDocument3 pagesFood For Thought English As A Medium of Instruction Web in ArTô Như QuỳnhNo ratings yet

- Effect of Instructions in Course Book Tasks On Promoting Higher-Order Thinking SkillsDocument9 pagesEffect of Instructions in Course Book Tasks On Promoting Higher-Order Thinking SkillsJuliana VivianiNo ratings yet

- 6thVESALCon PaperemankhalilmodifiedDocument8 pages6thVESALCon PaperemankhalilmodifiedSoniaNo ratings yet

- Made Hery Santosa - Current Research in ELTDocument7 pagesMade Hery Santosa - Current Research in ELTRi BianoNo ratings yet

- 4.1 Digital Equity Article Flip To Be Fair To Your ELLs TRIPSADocument14 pages4.1 Digital Equity Article Flip To Be Fair To Your ELLs TRIPSAMargo TripsaNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity - TESOL FinalDocument14 pagesLearning Activity - TESOL FinalLaurelGilmoreNo ratings yet

- MNUSCRIPT-MINH FinalDocument14 pagesMNUSCRIPT-MINH Finaltuyettran.eddNo ratings yet

- Sample ProposalDocument67 pagesSample ProposalGiancarla Maria Lorenzo Dingle100% (1)

- A Developmental Perspective On Technology in Language EducationDocument23 pagesA Developmental Perspective On Technology in Language EducationPrincess KongNo ratings yet

- 16 PDFDocument7 pages16 PDFSarang Hae Islam100% (1)

- Applying Role-Playing Strategy To Enhance Learners Writing and Speaking Skills in EFL Courses Using Facebook and Skype As Learning Tools A Case StudDocument25 pagesApplying Role-Playing Strategy To Enhance Learners Writing and Speaking Skills in EFL Courses Using Facebook and Skype As Learning Tools A Case StudNatashya ChambaNo ratings yet

- JEELS (Journal of English Education and Linguistics Studies), 6 (1), 25-50Document2 pagesJEELS (Journal of English Education and Linguistics Studies), 6 (1), 25-50Student MailNo ratings yet

- Whole Paper of JoliusDocument11 pagesWhole Paper of Joliusjoerald02 cailingNo ratings yet

- Inter and Intra-Culture-Based Group Disc PDFDocument26 pagesInter and Intra-Culture-Based Group Disc PDFStudent MailNo ratings yet

- 13 - Resume Socio and EducationDocument3 pages13 - Resume Socio and Educationanida nabilaNo ratings yet

- Paper 4Document21 pagesPaper 4Nguyễn Quốc CườngNo ratings yet

- Metaphorical Descriptions of Teaching and Learning of English During PandemicDocument11 pagesMetaphorical Descriptions of Teaching and Learning of English During PandemicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 1 (4) 02Document14 pages1 (4) 02datarian rianNo ratings yet

- Paper 3Document21 pagesPaper 3doductrung20022211No ratings yet

- د.انعام وميساء (بحث التنمية المستدامةDocument17 pagesد.انعام وميساء (بحث التنمية المستدامةMaysaa Al TameemiNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Speaking Anxiety of Thai Students During Oral Presentation: Faculty of Education in TSAIDocument10 pagesFactors Affecting Speaking Anxiety of Thai Students During Oral Presentation: Faculty of Education in TSAIRoffi ZackyNo ratings yet

- International Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishDocument8 pagesInternational Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishFauzi AbdiNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis On Bilingual EducationDocument6 pagesMaster Thesis On Bilingual Educationkezevifohoh3100% (2)

- Coad Jacquie s268872 Etp420 Assignment1Document6 pagesCoad Jacquie s268872 Etp420 Assignment1api-251186188No ratings yet

- Technology in The Language Classroom How PDFDocument14 pagesTechnology in The Language Classroom How PDFLisa TalNo ratings yet

- Ccab 096Document9 pagesCcab 096Hồng NgọcNo ratings yet

- International Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishDocument9 pagesInternational Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishFauzi AbdiNo ratings yet

- Fix - Kahoot! For EFLDocument12 pagesFix - Kahoot! For EFLBryna Albright WiladiNo ratings yet

- Biliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative PedagogyDocument4 pagesBiliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative PedagogybebechiNo ratings yet

- Cummins-Biliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative Pedagogy.Document17 pagesCummins-Biliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative Pedagogy.bebechiNo ratings yet

- 6Document5 pages6Yuriy KondratiukNo ratings yet

- Teaching English PronunciationDocument7 pagesTeaching English PronunciationClara LiraNo ratings yet

- Ajayi, 2008Document25 pagesAjayi, 2008alice nieNo ratings yet

- Multimodal Pedagogies in Teaching English For Specific Purposes in Higher Education: Perceptions, Challenges and StrategiesDocument6 pagesMultimodal Pedagogies in Teaching English For Specific Purposes in Higher Education: Perceptions, Challenges and StrategiesIrsyad Nugraha, M.Pd.No ratings yet

- The Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationDocument17 pagesThe Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationSoraya GilNo ratings yet

- Emerging Technologies, Emerging Minds - Digital Innovations Within The Primary SectorDocument4 pagesEmerging Technologies, Emerging Minds - Digital Innovations Within The Primary Sectormarina guevaraNo ratings yet

- Ccna HCL Exam QuestionsDocument25 pagesCcna HCL Exam Questionsshyam80No ratings yet

- Distinctive Aspects of ST John's Gospel I.E. Not Shared by The Synoptic GospelsDocument1 pageDistinctive Aspects of ST John's Gospel I.E. Not Shared by The Synoptic GospelsAnonymous NyT10DsFvNo ratings yet

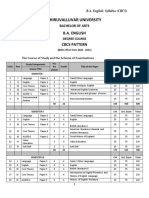

- B.A. English Literature SyllabusDocument91 pagesB.A. English Literature SyllabusS. GnanaprakashNo ratings yet

- MCQs For Class 10 MathematicsDocument4 pagesMCQs For Class 10 MathematicsKRISH VIMAL100% (1)

- HCI Lab 5Document8 pagesHCI Lab 5Agha Muhammad Yar KhanNo ratings yet

- Ra ReflectionDocument2 pagesRa Reflectionapi-337667370No ratings yet

- Intoduction To ItDocument123 pagesIntoduction To ItArpoxonNo ratings yet

- PIU11034-A-SEM202-202021 102645756 1110609193 Critical Evaluation of Malebranche S Occasionalism and BerkeDocument5 pagesPIU11034-A-SEM202-202021 102645756 1110609193 Critical Evaluation of Malebranche S Occasionalism and BerkemallgrajNo ratings yet

- Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street Editors PrefaceDocument5 pagesAnn Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street Editors Prefacemj cruzNo ratings yet

- LP Day 4 (Figure of Speech)Document6 pagesLP Day 4 (Figure of Speech)BelmerDagdagNo ratings yet

- 05 Quiz 1Document5 pages05 Quiz 1Muhamad Rais Abd HalimNo ratings yet

- Christiaan Kappes The Immaculate ConceptionDocument220 pagesChristiaan Kappes The Immaculate ConceptionVasilie ValentinNo ratings yet

- Ingles Orden de Los AdjetivosDocument3 pagesIngles Orden de Los AdjetivosJosé Antonio Romero100% (1)

- CH 13 Transmitting KnowledgeDocument3 pagesCH 13 Transmitting KnowledgeYoshita ShahNo ratings yet

- Regular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund Spanish Regular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund SpanishDocument2 pagesRegular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund Spanish Regular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund SpanishAna Maria Alvarado HernandezNo ratings yet

- SAhmad Project-1Document39 pagesSAhmad Project-1abdulrahmanabdulhakeem2017No ratings yet

- SAP Cloud Platform Daypo Test C CP 11.XMLDocument10 pagesSAP Cloud Platform Daypo Test C CP 11.XMLprognostechNo ratings yet

- 300+ React Js Interview Questions With AnswersDocument157 pages300+ React Js Interview Questions With AnswersMukesh Mangal100% (1)

- List Sách Grade 6Document6 pagesList Sách Grade 6SeCo ThienThan YeuAnh HonEmNo ratings yet

- 8.6.8.6 D DCM Hymn TunesDocument10 pages8.6.8.6 D DCM Hymn TunesAdam ThomasNo ratings yet

- BhashaIME User Reference 712Document12 pagesBhashaIME User Reference 712Madhu ChanNo ratings yet

- System Error Codes (12000-15999) (Windows)Document48 pagesSystem Error Codes (12000-15999) (Windows)miguel4711No ratings yet

- Agilent Technologies, 34980 Multifunction Switch&Measure PDFDocument349 pagesAgilent Technologies, 34980 Multifunction Switch&Measure PDFLulu Sweet ThingNo ratings yet

- Speech Choir Judging CriteriaDocument3 pagesSpeech Choir Judging CriteriaLiezl Sabado100% (2)

- 3 Pre Colonial Philippine Culture and Ancient Filipino Social HierarchyDocument27 pages3 Pre Colonial Philippine Culture and Ancient Filipino Social HierarchyIvy PamisaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 HCIDocument22 pagesModule 1 HCIMELANIE LADRILLO ABALDENo ratings yet

- 15 - JOB - INTERVIEW - Grille - D - Eval Job InterviewDocument1 page15 - JOB - INTERVIEW - Grille - D - Eval Job InterviewFrancoiseNo ratings yet

- 35593Document194 pages35593Irfan Rizq100% (1)

- Office 2007 IntroductionDocument19 pagesOffice 2007 Introductionslimhippolyte100% (8)

English Language Learning Apathy - An Agender Problem in Technical Vocational Education and Training

English Language Learning Apathy - An Agender Problem in Technical Vocational Education and Training

Uploaded by

oojerinde9726Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

English Language Learning Apathy - An Agender Problem in Technical Vocational Education and Training

English Language Learning Apathy - An Agender Problem in Technical Vocational Education and Training

Uploaded by

oojerinde9726Copyright:

Available Formats

OJERINDE, OLATUNDE ADEYEMI

+234 706 259 7915 / olatundeoje4@gmail.com

Topic: English language learning apathy: An agender problem in Technical

Vocational Education and Training.

Introduction

There is a deepening crisis of apathy towards English language learning, generally among

students of institutions of higher learning, and specifically among Technical and Vocational

Education and Training (TVET) trainees. This lack of interest is more distressing because of the

consequential communicative incompetence of both female and male learners. English occupies

a delicate position in the Nigerian educational system. Delicate because the neglect of English

has a direct negative impact on the whole system due to its historic position, economic

implications, social status, global stature, and the democratized nature of knowledge. Unlike

other crises that have plagued our educational system, the problem of learners’ apathy towards

learning English is systemically agender because it is common to both female and male students.

Conceptualisation

The English Language: the English language is perceived by an average Nigerian as a

colonial language; hence, a colonial inheritance. However, English has metamorphosed from

being an inheritance to a property. It has transformed itself and its users to a degree that both

cannot separate their paths. According to Akande and Okanlawon (2011), “English performs a

useful function in a multilingual society and will continue to do so” (p. 199). And beyond

Nigeria, “the status of English as a world language due to its spread over most of the world is no

longer an issue of debate. English is one of the most widely used and spoken languages in the

world today” (Nsungo, 2020, 176). English performs critical roles and functions in the Nigerian

society including being the most popular official language and the most used foreign language

that connects Nigerians within and to the world.

Learners’ Apathy: The evolution and status of English in Nigeria, consequent upon its

roles, have compelled attitudinal changes towards its learning. Due to many functions it performs

in Nigeria, “attitudes to the language have changed since colonial times” (Akande and

Okanlawon, 2011, p. 200). According to Akande and Okanlawon (2011), “reasons for learning

English now are more pragmatic in nature and run counter to Phillipson’s argument that those

who acquire the language…are victims of linguistic imperialism” (200). This assertion

emphasises the importance of English against the fact of its colonial origin.

However, the apathetic attitude of learners runs counter to the pragmatism of English

usage in our educational system, particularly its role in TVET. It is counter-productive for a

learner in vocational studies to ignore or treat with levity, the learning of English in a world that

is dominantly shaped by the language. Thus, it is distressing that students are, in today’s

borderless world, apathetic toward English learning. Their insouciance is seldom expressed

jokingly as “good English does not translate to intelligence”. This assertion, which attempts to

separate intelligence from good communication skills, is reflective of the hostility learners have

developed and harboured for English. This could be symptomatic of their difficult struggle with

basic skills of English and can as well be a pointer to a faulty syllabus. Meanwhile, as plausible

as that expression may seem, more factual is intelligence and competence cannot be complete

without good communication skills. In the context of the Nigerian education system, competence

is jaundiced without good communication skills, in English.

Agender Nature of the Problem: It must be specially noted that a problem is a problem,

not a challenge. A strange trend in the culture of religiosity which has elevated motivational talk

shows has muddled the meaning of “problem” and “challenge”. According to Oyegoke (2011):

recent motivational talk culture gives out that “problem” is denotatively negative and

therefore problematic in usage; it suggests as a more salubrious substitute, the English

word “challenge”. The thinking is that “problem” is a psychological/spiritual stone-wall

that instills fear and negates actions, while “challenge” extracts a more positive, more

pragmatic reaction to the issue or situation that is being captured in words” (p. 3).

Unfortunately, that semantic muddling has erased the actual meaning of “challenge” and

simply uses the word with the same semantic implication as that of a “problem”. A problem in

all its semantic and pragmatic implications is used here to mean a “source of perplexity, distress,

or vexation” (Merriam-Webster). It is “’a matter difficult of settlement or solution… and also, a

proposition in which something is required to be constructed” (Oyegoke, 2011, p. 4). The

discussion of learners’ apathy towards English language learning should not be semantically

obfuscated. It is a source of perplexity and vexation that transcends barriers of genders. The term

agender is used figuratively to project the problem as common to both genders without

identifying as peculiar to either.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

Pace (2021) defined Vocational Education and Training as “education and training which aim to

equip people with knowledge, know-how, skills and/or competencies required in particular

occupations or more broadly on the labour market” (p. 233). As West (2012) put it, the meaning

of VET has shifted from denoting:

a fairly specific training or re-training for particular jobs to a very wide concept,

overlapping with general education and spanning, in theory at least, secondary

education, adult training both general and in connection with active labour market

measures, much of the higher education and lifelong learning as a whole. (p. 19).

Basically, TVET has expanded in its scope due to certain factors including sophisticated

technology which requires greater competences for both teachers and learners. Pace (2021)

averred that “the rapidity of technological and social change, the dramatic shifts from agrarian or

industrial eras to the knowledge era and beyond…have impacted on countries and economies

across the world (p. 234). These factors and trend have combined to alter the idea and notion of

VET. For Pace (2021), “VET is no longer a limited career associated with higher degree labour

with less cognitive demand. It now requires higher degree of skills and finesse” (p. 234).

The question therefore is, can VET trainees, as well as trainers and institutions, in spite of

these factors and heightened cognitive requirement of sophisticated competences afford to brood

hostile attitude towards learning English language in the realities of a fast pace globalization?

This question has become imperative in view of the growing apathy towards English language

which is now at crisis level beyond gender barriers. This will be further expounded under the

sub-headings: Communicative Competence in TVET, Privileging English language and Current

Approach and Suggestions.

Communicative Competence in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

Competence is “the ability to carry out a real, vital action and the qualification

characteristics of an individual, taken at the time of his inclusion in the activity” (Jalilovna, 2020,

p. 88). Competence is directly connected to performances and actions in specific time that can be

measured. Often times, different competences or skills set are required for a successful

performance. In VET, different competences have been identified using different competency

models. According to Jalilovna (2020), “competency model is a set of competences required to

successfully complete a given job [involving] wide variety of knowledge, abilities, skills and

individual personality characteristics” (p. 90).

Scholars have identified different models of pedagogical competence of vocational

teachers/learners in the context of sustainable development. According to Diep and Hartmann

(2016), “competences are always solid due to broad knowledge which is classified into

professional declarative and procedural knowledge” (p. 3). On the one hand, declarative

knowledge is mentally representational understanding expressed in semantic networks. In other

words, a verbal description denoting that “someone is aware of the knowledge and can verbalise

it” (p. 3). On the other hand, procedural knowledge is “embodied knowledge: how to do

something successfully” (Diep and Hartmann 2016, 3). Other scholars (Terhat, 2000, 55; Kosinar

2014, 32; Carle 2002, 10) as cited by Diep and Hartmann (2016), have expanded this

competence domain to include “action routines and forms of reflection”; therefore competence is

hinged scientifically sound knowledge, situational flexible applicable routines, and on specially

professional ethics representing the action guiding standards of value” (p. 3). Shulman (1987),

cited by Diep and Hartmann (2016), also classified pedagogical competence into five main

dimensions:

(1) general pedagogical knowledge relating to broad principles and strategies of

classroom management and organisation, (2) subject-matter content knowledge, (3)

pedagogical content knowledge, (4) curricular knowledge, (5) other knowledge with

reference to knowledge of educational context, knowledge of learners and their

characteristics, knowledge of educational purposes, values and their philosophical

historical grounds. (pp. 32-32).

Diep and Hartmann (2016) proposed a six-area model which expanded other scholars’

(Shulman’s (1987, 32), Terhat, (2000, 55), Kosinar (2014, 32), Carle (2002, 10) models to

include communicative and language competence. The six intertwined areas are “(i) teaching

competence, (ii) educating competence, (iii) professional competence, (iv) competence of linking

real work processes with professional learning processes, (v) competence of self-reflection and

improving the qualification and (vi) communicative and language competence” (pp. 7-11). Diep

and Hartmann (2016) discussed competences from a pedagogical perspective. This view suggests

vocational teachers were their main concern. However, these pedagogical competences are

apposite to learners particularly because VET students in teacher training institutions are equally

potential teachers.

Diep and Hartmann (2016) defined communicative and language competence as the

“ability to use language and communicative skills to convey the learning content logically and

attractively, to convince and to advise the vocational learners, to educate them as well as to help

them in learning processes” (p. 10). It is basically “the ability to communicate well in a

language” (Macmillan).

It is important to note the difference between coomunicative competence and linguistic

competence. According to Jalilovna (2020) “communicative language competence can be

considered as comprising several components: linguistic, sociolinguistic and pragmatic” (p. 89).

It is however clear that learners tend to confuse linguistic competence for communicative

competence because they are more concerned with linguistic competence which is restrictive and

often leaves them with the knowledge of grammar of English without the ability to use English.

Jalilovna (2020) observed that students learning English are:

not equipped with necessary tools that should enable them to take part in a two-way

dialogue in English as they found themselves incapable of expressing their emotions,

feelings, agreements, likes and dislikes in an English context [because] instead of

acquiring ways of using language in meaningful situations to produce meaningful acts of

communication, they have mastered formation rules of the language. (p. 89).

The distinction between linguistic competence and communicative competence is of great

import to understanding the fault lines in learners’ incompetence in relation to their syllabus.

Linguistic competence is limited to tacit knowledge of language structures which include units of

grammar and punctuations. However, communicative competence entails ability to use language

in real life situation. What is obtainable today is that students can clearly tell about the four skills

of language --listening, speaking, reading and writing, only in theory without the ability to read

and write at expected level of competence. Reading and writing are major skills of literacy and

germane to learning process. Listening and reading are also vital skills because they are receptive

language skills that enable students to receive information in lecture rooms and printed materials

as well as electronic copies of study materials. Hence, the required level of competence needed

by students in tertiary institutions to absorb information is relatively high. Most importantly, all

these must be done using English language. In other words, communicative and language

competence for Nigerian students of VET compels mastery of the language of communication

which is English. This inevitably privileges English language in Nigeria.

Privileging English language

According to Jalilovna (2020):

…the successful adaptation of a student of a tertiary higher educational institution at an

enterprise largely depends on them by a set of professional competences acquired during

their studies at a higher educational institution. In our opinion, one of the most necessary

for the formation of the professional competence…is the communication competence. (p.

90).

In Diep and Hartmann’s (2016) competence model for TVET, unlike in other scholars’,

communicative and language competence is foregrounded because “the role of communication

has increased in modern society due to the growth and expansion of interpersonal, inter-regional

and international relations” (p. 11) and, with the increasing numbers of information driven

societies and expansion of social experience, communicative competence has become “critical in

situations of public speaking, debate, dispute, negotiation, meetings, presentations, industrial

conflict resolution” (Burganova and Valeev, 2015, p. 79).

In the Nigerian context, English is synonymous with communication across many strata

of the society, educational sector in particular. Therefore, English retains its privileged status not

because of colonial or political hegemony but because of the pragmatism that defines the nature

of today’s globalized world where most communicative acts are done in English as alluded to by

Akande and Okanlawon (2011). It is therefore contradictory that with all the privileges good

communication skills command, learners are apathetic towards learning English. This apathy

borders on hostility and it has reached a point of crisis that requires urgent actions to effect

attitudinal changes.

Akande and Okanlawon (2011) observed that “reasons for learning English now are more

pragmatic in nature (p. 200) aside the fact that “English occupies a historic position in Nigeria”

(Oyegoke 2010, p.1). English has become a part of our culture, particularly our educational

process from the lowest level to the highest level, notwithstanding the national policy on the use

of indigenous languages at the primary school level. In addition, English has a global role that

commands great advantages and consequently bestows privileges on its users. The subject of its

relevance and consequential privilege continues to be a discourse focus in “ideological and

cultural debates” (Oyegoke 2010, p.1). However, the important roles and functions in Nigeria

cannot be ideologically wished away.

In a reminiscent tone, Oyegoke (2010) examined that:

…up till the early 1980s English was doing reasonably well in this country [as] majority

of the users of the language understood it as such: a language…. There was fondness for

the language for a number of reasons: (i) English was the language used by erstwhile

colonialists; (ii) English had become the official post-colonial language; (iii) English had

become the language of the intellectual elite; (iv) English was the language of political

elite; (v) English was a mark of education, erudition and power; (vi) English was

procured as an item of influence and respectability; (vii) English was above all, a vital

instrument of communication locally and internationally. (p. 2).

All these have yet to change and in addition to reasons Oyegoke (2010) adduced, English has

today become more embellished with greater influence and privilege.

According to Lazaro and Medalla (2004), “English is far more worldwide in its

distribution than all other spoken languages. It is an official language in 52 countries as well as

many small colonies and territories. It has become the most useful language to learn for

international travel and is now the de facto lingua franca of diplomacy” (p. 278). More

importantly in a technologically advanced world, “about 75 percent of the world’s mail, telexes

and cables are in English. Approximately 60 percent of the world’s radio programs are in English

as well as about 90 percent of all internet traffic” (p. 279). Lazaro and Medalla (2004) averred

that “money and language shared similar characteristics…just as money allows society to move

beyond barter, a common language also facilitates transactions and lower cost [because] learning

language is in itself a growth industry in the world” (p. 281).

The Economist (2021) cited in Pace (2021) opined that “language has replaced work visa

as the main barrier to mobility”. This is particularly apt for students in the third world who may

not have visas to travel around the world; but, through sufficient language skills can take

advantage of globalization and virtual integration of the world to absorb knowledge from every

part of the world without impediments. The essential role of learning English is critical to

students’ personal development as the mastery of English is “considered not just an excellent

tool to bridge gaps but above all an instrument that enables them to considerably improve their

career prospects with several studies showing a very close connection between proficiency in

languages and employability” (Pace, 2021, p. 235).

Beyond the undisputed privileged status of English in today’s world, English should be

considered a tool in VET and not a mere subject. Learners must be guided and supported to

understand this perception while teachers and institutions must “entool” English as a vital

content of vocational training. “The English language skill has become a necessity for

establishing linkages with the rest of the world in international trade, economic development and

even in the use of technology” (Lazaro and Medalla 2004, p. 278). English communicative

competence guarantees a competitive advantage among learners, nationally and internationally.

English proficiency is a special kind of skill that is needed to upgrade other skills, particularly

for learners, who are also future workers and teachers, to participate in a flexible and

multitasking work environment.

Another important advantage of English is its dominance of technology and internet

space. English is adjudged the language of the internet accounting for 36% online language

population with Chinese coming a distant second at 14% (Lazaro and Medalla, 2004). The

implication of this is that the knowledge of English will strengthen and expand the net of

knowledge, information, and skills learners can access from the internet. In addition to what may

be acquired, the ability to also contribute effectively to global conversations in economic

discourse is greatly enhanced. “With English being the primary language of research and

development and science and technology, having English language skills is of critical importance

in terms of acquiring and deepening IT knowledge” (Lazaro and Medalla, 2004, p. 283). This

becomes particularly inevitable in a transiting economy where a labour-intensive manufacturing

is being phased out by a technology-intensive model which compels more sophisticated

knowledge.

Therefore, the enthronement of ignorance chiefly through apathy by learners cannot be

allowed to fester on for too long. There have to be deliberate efforts to change the problem of

attitude which has become a major constraint in achieving VET’s trainees’ potential. Learners

must be supported to have a positive disposition towards learning English as well as appreciate

the value of the privilege good communicative competence will attract to their ambition.

Current Approach:

The frantic dynamism that technological advancement has brought to the world compels

continuous evaluation of educational systems including teaching methods and curriculum

contents. The evaluation, according to Pace (2021) is not only “regarding innovative and

digitally based learning/teaching methods, but also with an even stronger focus on lifelong

learning competencies and transversal skills [including] ability to acquire new skills and

competencies [and] to further develop existing skills” (p. 234). With the expansion of the scope

of VET, the need for new skills and competencies has placed distributed burden on trainees,

trainers, and institutions. It, therefore, becomes imperative for students to acquire these new

skills and competencies in order to be relevant and become agents of change in the drive to

evolve a knowledge economy driven cognitively at the expense of erstwhile labour intensity.

Pace (2021) opined that “one very effective way that can help VET students to acquire

such skills is through international mobility, as this provides the opportunity of enhancing

cooperation and of sharing good and effective practices” (p. 234). In other words, VET must

necessarily be de-localised to attain optimal potential. The idea of international mobility does not

compel students to travel around the world; rather, it compels students to function beyond the

confines of their locale or national borders in a way that will nourish and “increase their human,

social and cultural capital”. Pace (2021) explained students’ international mobility as their ability

to “gain international experience, get to know different cultures, improve their language skills,

and develop a more cosmopolitan identity, which in turn all contribute to their personal

development” (p. 234).

What is apparent in VET today is that learners have lost desire to acquire English skills to

a degree they can use it to communicate effectively. The extant interventions in form of policies

that made English a compulsory subject at O’level and also a course in the General Studies for

students in tertiary institutions have proven, at best, inadequate. What these two policies have

achieved is the teaching of “rudiments of linguistic” in an attempt “to correct deficiencies in the

acquisition of English” (Oyegoke, 2010). Oyegoke (2010), over a decade ago, noted with

emphasis that:

…all the formal drilling in grammar and other linguistic information encouraged by

OUTWORN (emphasis is mine) English syllabuses at various levels may be unable to

deliver the kind of benefit [desired]. It only feeds the rote and mechanical potential of the

learners of English and produces someone who knows more about English than is able to

use English correctly. (p. 10).

Oyegoke’s position clearly suggested that alongside the attitude of the learners, education

planners need to reevaluate the content being taught to ascertain competence is prioritised over

mere linguistic knowledge. Students should know how to use English rather than merely

cramming information about English. An average student will define a verb, a noun, an

adjective, an adverb but very few are able to write a simple essay coherently. This system of

teaching English at tertiary institutions could have contributed greatly to the disinterestedness

learners are showing today as it appears uninspiring to learn virtually the same set of rules and

rudimentary linguistic details from early classes up to tertiary levels. This is a point that requires

the attention of policy makers and educationists.

Conclusion

The attitude of the learners can be considered from the general economic gloom for better

understanding of the nexus between national economy and learners’ apathy. It will be equivocal

to blame the gloomy economy for learners’ apathy as some of them would like to advance as an

argument. High unemployment is, sometimes, blamed for learners’ low motivation to excel in

school because the thought of graduating without a job can be overwhelming. This claim is

however equivocal. The position here however is that the gloom should rather be a motivation

for learners to excel so as to stand a better chance among their peers. The tendency to emphasize

future uncertainty as a reason to fail to learn while in school simply worsens the situation, for the

individual learners and the economy.

In addition to learners’ attitude that putatively stems from economic gloom, their

motivation as well as their orientation are negatively wrought against learning English. Many

learners are in vocational education and training fields with a clear goal to acquire concrete skills

that will either make them ready for gainful employment after school or that which will make

them self-employed. They consider these skills as their main focus and as such considers

language skills as abstract and unconnected to their primary goal. Therefore, they are least

motivated to improve their core English language skills which are key to their overall success.

They, wrongly and unfortunately, consider English less important and unconnected to their

primary skill acquisition. They have continued to nurture negative memories of English studies

from their secondary school education, particularly when writing their terminal and/or

transitional examinations like SSCE and JAMB, and have failed to appreciate the relevance of

good communicative competence to their lives and future careers. Thus, low motivation and

hostile orientation towards English have grown unwavering disinterestedness in students of VET

thereby negatively impacting their competitiveness on the labour market after graduation.

Suggestions

There is a wide gap between what is needed and what is being offered to students and this

has obviously affected their competence which has now gone worse with sheer ineptitude and

apathy to learn English. We will make two suggestions that can change learners’ attitudes and

halt the problem of communicative incompetence among VET students. The first suggestion is a

shift from studying English as a general course to studying English for Specific Purpose (ESP).

ESP will ensure content is tailored to needs against what is obtainable in GSE/GNS where

content is rudimentary and general, as the name connotes. This does not have to be enforced at

the macro level that includes all students in institutions of higher learning even though that is

most preferred; rather, communicative competence needs can be evaluated and content

[re]designed at a micro level within the school of VET so as to enhance VET’s learners’ overall

readiness to thrive in a globalized world.

Secondly, and more importantly, is that literature must be incorporated as a major content

of English studies because nothing teaches language better than literature. Learning English with

much focus on rudimentary linguistics has proven ineffective in achieving the primary objective

of communicative competence. The current trend overtly emphasizes formal analysis of language

with inadequate content on actual usage of English which can be found only in literature. There

is no better way to teach a language other than through literature. It is not to suggest that VET

students should only read novels and William Shakespeare’s plays or John Milton’s epic poems;

but, curriculum experts must understand that the idea of teaching English cannot be

accomplished without involving practice with English and the best practice is literature.

The benefits of literature are many. One of it is pleasure or entertainment. When people

read literature, good literature, of course, makes the language itself attractive because of creative

usage that projects the aesthetics of the art. Also, many readers will learn new words and

expressions that will not be found anywhere but in literature. This will enhance readers’

awareness of language in real situations instead of abstract examples used to explain linguistic

rules. In addition, the correct form of usage will be lodged in the subconscious of readers of

literature written in good English while they grow their vocabulary effortlessly. The problem of

apathy towards English learning in a world that is driven by English is a consequence of a failing

national educational system cum policy that requires an immediate response. To halt this

negative trend, deliberate action must be taken, attitudinal change must be compelled and

literature must be incorporated in English studies.

REFERENCES

Akande, A. T. & Okanlawon, B. O. (2011). Standard English in Nigerian graduates’ speech.

Gege: Ogun Studies in English: 8:196—214

Burganova, N. T. & Valeev, A. A. (2015). Development of technical college students’

communicative competence. Review of European Studies, 7(5), 79—90

Diep, P. C. & Hartmann, M. (2016). Green skills in vocational teacher education—a model

pedagogical competence for a world of sustainable development. TVET@Asia, 6, 1—19.

http://www.tvet-online.asia/issue6/diep_hartmann_tvet6.pdf

Jalilovna, J. N. (2020). Communicative competence and its implication for teaching and

learning. International Journal of Engineering and Information Systems, 4(12) 88—91

Lazarro, D. C. & Medalla, E. M. (2004). English as the language of trade, finance and

technology in APEC: An East Asia perspective. Philippine Journal of Development 58(2)

277--300

Macmillan Dictionary. https://www.macmillandictionary.com/ Date retrieved: 10/Nov./2022

Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/ Date retrieved: 10/Nov./2022

Nsungo, D. P. (2020). The intelligibility of non-native English: A re-occurring index in second

language (L2) research. Journal of the English Scholars Association of Nigeria. 22(2)

176—188.

Oyegoke, L. (2010). Deepening crisis of English studies in Nigeria. Oye: Ogun Journal of Arts,

XVI 1--11

Oyegoke, L. (2011). Problematizing knowledge. Oye: Ogun Journal of Arts, XVII 1—12

Pace, M. (2021). Language learning and vocational education and training. Conference paper

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356459874/

Solodkova, I. M., Grigorieva, E. V., Ismagilova, L. R., & Polyakova, O. V. (2017). What drives

students of vocational training program? An investigation on the significance of foreign

language acquisition. Journal of History, Culture and Art research, 6(6), 96—103. Doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v6i6.132

You might also like

- Ebook PDF The Writers World Paragraphs and Essays With Enhanced Reading Strategies 5th Edition PDFDocument41 pagesEbook PDF The Writers World Paragraphs and Essays With Enhanced Reading Strategies 5th Edition PDFjames.lindon669100% (42)

- Literature Review-PBL and Blended LearningDocument12 pagesLiterature Review-PBL and Blended LearningBret GosselinNo ratings yet

- Language and Society-Research ProposalDocument8 pagesLanguage and Society-Research Proposalp3tru_mzq100% (2)

- Concept-Paper-U R E C S - TVL-StudentsDocument12 pagesConcept-Paper-U R E C S - TVL-Studentssinino3735No ratings yet

- Definition and Design: Aligning Language Interventions in EducationDocument16 pagesDefinition and Design: Aligning Language Interventions in EducationyutefupNo ratings yet

- EJ1297667Document13 pagesEJ1297667abaamran aylalNo ratings yet

- 472-Texto Del Artículo-2029-1-10-20160614Document26 pages472-Texto Del Artículo-2029-1-10-20160614JohnNo ratings yet

- Planning An Engaging SyllabusDocument8 pagesPlanning An Engaging SyllabusstavrosthalisNo ratings yet

- Biesta AgainstLearningDocument13 pagesBiesta AgainstLearningTina ZubovicNo ratings yet

- Bilingual Education Term PaperDocument5 pagesBilingual Education Term Paperc5rga5h2100% (1)

- EdD Assignment 3 Josephine V SalibaDocument27 pagesEdD Assignment 3 Josephine V SalibaJosephine V SalibaNo ratings yet

- Bilingual Education Thesis TopicsDocument8 pagesBilingual Education Thesis TopicsChristine Maffla100% (2)

- FinaloralmanuscrptDocument109 pagesFinaloralmanuscrptHazelBautistaNo ratings yet

- ESP Issues Article by Abdelfatteh HarrabiDocument20 pagesESP Issues Article by Abdelfatteh Harrabireem_boubakerNo ratings yet

- Empowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyDocument12 pagesEmpowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyAngely Chacón BNo ratings yet

- RESEARCHDocument29 pagesRESEARCHbugtongshana0No ratings yet

- Teaching For Learner Differences: Literature ReviewDocument17 pagesTeaching For Learner Differences: Literature Reviewfebri eka saputraNo ratings yet

- 3 Statement of The ProblemDocument17 pages3 Statement of The ProblemCharlton BrutonNo ratings yet

- Bilingualism PDFDocument13 pagesBilingualism PDFFarah MalikNo ratings yet

- Bond (2019) International Students Language Culture and The Performance of IdentityDocument18 pagesBond (2019) International Students Language Culture and The Performance of Identityspaceship9No ratings yet

- Sahibah Aguero Department of English Education, University of Syiah Kuala, IndonesiaDocument8 pagesSahibah Aguero Department of English Education, University of Syiah Kuala, IndonesiaRaziSyukriNo ratings yet

- Scaffolding in An EFL ClassroomDocument10 pagesScaffolding in An EFL ClassroomYuyun Yurnaningsih SuhendiNo ratings yet

- Food For Thought English As A Medium of Instruction Web in ArDocument3 pagesFood For Thought English As A Medium of Instruction Web in ArTô Như QuỳnhNo ratings yet

- Effect of Instructions in Course Book Tasks On Promoting Higher-Order Thinking SkillsDocument9 pagesEffect of Instructions in Course Book Tasks On Promoting Higher-Order Thinking SkillsJuliana VivianiNo ratings yet

- 6thVESALCon PaperemankhalilmodifiedDocument8 pages6thVESALCon PaperemankhalilmodifiedSoniaNo ratings yet

- Made Hery Santosa - Current Research in ELTDocument7 pagesMade Hery Santosa - Current Research in ELTRi BianoNo ratings yet

- 4.1 Digital Equity Article Flip To Be Fair To Your ELLs TRIPSADocument14 pages4.1 Digital Equity Article Flip To Be Fair To Your ELLs TRIPSAMargo TripsaNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity - TESOL FinalDocument14 pagesLearning Activity - TESOL FinalLaurelGilmoreNo ratings yet

- MNUSCRIPT-MINH FinalDocument14 pagesMNUSCRIPT-MINH Finaltuyettran.eddNo ratings yet

- Sample ProposalDocument67 pagesSample ProposalGiancarla Maria Lorenzo Dingle100% (1)

- A Developmental Perspective On Technology in Language EducationDocument23 pagesA Developmental Perspective On Technology in Language EducationPrincess KongNo ratings yet

- 16 PDFDocument7 pages16 PDFSarang Hae Islam100% (1)

- Applying Role-Playing Strategy To Enhance Learners Writing and Speaking Skills in EFL Courses Using Facebook and Skype As Learning Tools A Case StudDocument25 pagesApplying Role-Playing Strategy To Enhance Learners Writing and Speaking Skills in EFL Courses Using Facebook and Skype As Learning Tools A Case StudNatashya ChambaNo ratings yet

- JEELS (Journal of English Education and Linguistics Studies), 6 (1), 25-50Document2 pagesJEELS (Journal of English Education and Linguistics Studies), 6 (1), 25-50Student MailNo ratings yet

- Whole Paper of JoliusDocument11 pagesWhole Paper of Joliusjoerald02 cailingNo ratings yet

- Inter and Intra-Culture-Based Group Disc PDFDocument26 pagesInter and Intra-Culture-Based Group Disc PDFStudent MailNo ratings yet

- 13 - Resume Socio and EducationDocument3 pages13 - Resume Socio and Educationanida nabilaNo ratings yet

- Paper 4Document21 pagesPaper 4Nguyễn Quốc CườngNo ratings yet

- Metaphorical Descriptions of Teaching and Learning of English During PandemicDocument11 pagesMetaphorical Descriptions of Teaching and Learning of English During PandemicInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 1 (4) 02Document14 pages1 (4) 02datarian rianNo ratings yet

- Paper 3Document21 pagesPaper 3doductrung20022211No ratings yet

- د.انعام وميساء (بحث التنمية المستدامةDocument17 pagesد.انعام وميساء (بحث التنمية المستدامةMaysaa Al TameemiNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Speaking Anxiety of Thai Students During Oral Presentation: Faculty of Education in TSAIDocument10 pagesFactors Affecting Speaking Anxiety of Thai Students During Oral Presentation: Faculty of Education in TSAIRoffi ZackyNo ratings yet

- International Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishDocument8 pagesInternational Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishFauzi AbdiNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis On Bilingual EducationDocument6 pagesMaster Thesis On Bilingual Educationkezevifohoh3100% (2)

- Coad Jacquie s268872 Etp420 Assignment1Document6 pagesCoad Jacquie s268872 Etp420 Assignment1api-251186188No ratings yet

- Technology in The Language Classroom How PDFDocument14 pagesTechnology in The Language Classroom How PDFLisa TalNo ratings yet

- Ccab 096Document9 pagesCcab 096Hồng NgọcNo ratings yet

- International Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishDocument9 pagesInternational Collaborative Learning, Focusing On Asian EnglishFauzi AbdiNo ratings yet

- Fix - Kahoot! For EFLDocument12 pagesFix - Kahoot! For EFLBryna Albright WiladiNo ratings yet

- Biliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative PedagogyDocument4 pagesBiliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative PedagogybebechiNo ratings yet

- Cummins-Biliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative Pedagogy.Document17 pagesCummins-Biliteracy, Empowerment, and Transformative Pedagogy.bebechiNo ratings yet

- 6Document5 pages6Yuriy KondratiukNo ratings yet

- Teaching English PronunciationDocument7 pagesTeaching English PronunciationClara LiraNo ratings yet

- Ajayi, 2008Document25 pagesAjayi, 2008alice nieNo ratings yet

- Multimodal Pedagogies in Teaching English For Specific Purposes in Higher Education: Perceptions, Challenges and StrategiesDocument6 pagesMultimodal Pedagogies in Teaching English For Specific Purposes in Higher Education: Perceptions, Challenges and StrategiesIrsyad Nugraha, M.Pd.No ratings yet

- The Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationDocument17 pagesThe Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationSoraya GilNo ratings yet

- Emerging Technologies, Emerging Minds - Digital Innovations Within The Primary SectorDocument4 pagesEmerging Technologies, Emerging Minds - Digital Innovations Within The Primary Sectormarina guevaraNo ratings yet

- Ccna HCL Exam QuestionsDocument25 pagesCcna HCL Exam Questionsshyam80No ratings yet

- Distinctive Aspects of ST John's Gospel I.E. Not Shared by The Synoptic GospelsDocument1 pageDistinctive Aspects of ST John's Gospel I.E. Not Shared by The Synoptic GospelsAnonymous NyT10DsFvNo ratings yet

- B.A. English Literature SyllabusDocument91 pagesB.A. English Literature SyllabusS. GnanaprakashNo ratings yet

- MCQs For Class 10 MathematicsDocument4 pagesMCQs For Class 10 MathematicsKRISH VIMAL100% (1)

- HCI Lab 5Document8 pagesHCI Lab 5Agha Muhammad Yar KhanNo ratings yet

- Ra ReflectionDocument2 pagesRa Reflectionapi-337667370No ratings yet

- Intoduction To ItDocument123 pagesIntoduction To ItArpoxonNo ratings yet

- PIU11034-A-SEM202-202021 102645756 1110609193 Critical Evaluation of Malebranche S Occasionalism and BerkeDocument5 pagesPIU11034-A-SEM202-202021 102645756 1110609193 Critical Evaluation of Malebranche S Occasionalism and BerkemallgrajNo ratings yet

- Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street Editors PrefaceDocument5 pagesAnn Fisher-Wirth and Laura-Gray Street Editors Prefacemj cruzNo ratings yet

- LP Day 4 (Figure of Speech)Document6 pagesLP Day 4 (Figure of Speech)BelmerDagdagNo ratings yet

- 05 Quiz 1Document5 pages05 Quiz 1Muhamad Rais Abd HalimNo ratings yet

- Christiaan Kappes The Immaculate ConceptionDocument220 pagesChristiaan Kappes The Immaculate ConceptionVasilie ValentinNo ratings yet

- Ingles Orden de Los AdjetivosDocument3 pagesIngles Orden de Los AdjetivosJosé Antonio Romero100% (1)

- CH 13 Transmitting KnowledgeDocument3 pagesCH 13 Transmitting KnowledgeYoshita ShahNo ratings yet

- Regular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund Spanish Regular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund SpanishDocument2 pagesRegular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund Spanish Regular Verbs Present Tense Past Tense Past Participle Gerund SpanishAna Maria Alvarado HernandezNo ratings yet

- SAhmad Project-1Document39 pagesSAhmad Project-1abdulrahmanabdulhakeem2017No ratings yet

- SAP Cloud Platform Daypo Test C CP 11.XMLDocument10 pagesSAP Cloud Platform Daypo Test C CP 11.XMLprognostechNo ratings yet

- 300+ React Js Interview Questions With AnswersDocument157 pages300+ React Js Interview Questions With AnswersMukesh Mangal100% (1)

- List Sách Grade 6Document6 pagesList Sách Grade 6SeCo ThienThan YeuAnh HonEmNo ratings yet

- 8.6.8.6 D DCM Hymn TunesDocument10 pages8.6.8.6 D DCM Hymn TunesAdam ThomasNo ratings yet

- BhashaIME User Reference 712Document12 pagesBhashaIME User Reference 712Madhu ChanNo ratings yet

- System Error Codes (12000-15999) (Windows)Document48 pagesSystem Error Codes (12000-15999) (Windows)miguel4711No ratings yet

- Agilent Technologies, 34980 Multifunction Switch&Measure PDFDocument349 pagesAgilent Technologies, 34980 Multifunction Switch&Measure PDFLulu Sweet ThingNo ratings yet

- Speech Choir Judging CriteriaDocument3 pagesSpeech Choir Judging CriteriaLiezl Sabado100% (2)

- 3 Pre Colonial Philippine Culture and Ancient Filipino Social HierarchyDocument27 pages3 Pre Colonial Philippine Culture and Ancient Filipino Social HierarchyIvy PamisaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 HCIDocument22 pagesModule 1 HCIMELANIE LADRILLO ABALDENo ratings yet

- 15 - JOB - INTERVIEW - Grille - D - Eval Job InterviewDocument1 page15 - JOB - INTERVIEW - Grille - D - Eval Job InterviewFrancoiseNo ratings yet

- 35593Document194 pages35593Irfan Rizq100% (1)

- Office 2007 IntroductionDocument19 pagesOffice 2007 Introductionslimhippolyte100% (8)