Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10.1056NEJMra1007236

10.1056NEJMra1007236

Uploaded by

Fabià Pla ConsuegraCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Acls Cheat Sheet PDFDocument3 pagesAcls Cheat Sheet PDFDarren Dawkins100% (4)

- Crash Cart Check ListDocument2 pagesCrash Cart Check ListAnonymous iG0DCOfNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Disorders Care Plan Nursing Care PlanDocument4 pagesBipolar Disorders Care Plan Nursing Care PlanAnne de Vera0% (1)

- Diaphragm Plication For Eventration or Paralysis (A Review of The Literature)Document5 pagesDiaphragm Plication For Eventration or Paralysis (A Review of The Literature)TommyNo ratings yet

- S2531043718301624 PDFDocument13 pagesS2531043718301624 PDFAnja LjiljaNo ratings yet

- Diaphragmatic Dysfunction: ReviewDocument13 pagesDiaphragmatic Dysfunction: ReviewJuani CantellanosNo ratings yet

- diaphragmatic paralysisDocument10 pagesdiaphragmatic paralysismokhtarNo ratings yet

- Diseases of The Diaphragm, Chest Wall, Pleura, and MediastinumDocument16 pagesDiseases of The Diaphragm, Chest Wall, Pleura, and Mediastinumjpma2197No ratings yet

- Assessment of Respiratory Muscle Function StrengthDocument8 pagesAssessment of Respiratory Muscle Function StrengthsstavrosNo ratings yet

- Eventratio DiafragmaDocument9 pagesEventratio DiafragmairenaNo ratings yet

- Referensi 7 PDFDocument5 pagesReferensi 7 PDFirfhanahusaNo ratings yet

- 2 enDocument10 pages2 enRaj SinghNo ratings yet

- Difficult Airway Management in A Patient With AchondroplasiaDocument2 pagesDifficult Airway Management in A Patient With AchondroplasiaabdulmajeedNo ratings yet

- Locked-In Syndrome: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument6 pagesLocked-In Syndrome: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchsakuraleeshaoranNo ratings yet

- Disorders of The DiaphragmDocument16 pagesDisorders of The DiaphragmFajar YuniftiadiNo ratings yet

- The Upper Airway During Anaesthesia: D. R. Hillman, P. R. Platt and P. R. EastwoodDocument9 pagesThe Upper Airway During Anaesthesia: D. R. Hillman, P. R. Platt and P. R. EastwoodFendy PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia Management in Acute and Sub-Acute StrokeDocument10 pagesDysphagia Management in Acute and Sub-Acute Strokeprima trisna ajiNo ratings yet

- MedBack MyelomeningoceleDocument3 pagesMedBack MyelomeningoceleJulia Rei Eroles IlaganNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Prune Belly Syndrome: Syndromic Vignettes in AnaesthesiaDocument2 pagesAnaesthesia For Prune Belly Syndrome: Syndromic Vignettes in AnaesthesiaIonut BaraNo ratings yet

- Piis2212440318300592 PDFDocument3 pagesPiis2212440318300592 PDFUmer HussainNo ratings yet

- Duane SindromDocument5 pagesDuane SindromAlwin SoetandarNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia Associated With Cervical Spine and Postural DisordersDocument12 pagesDysphagia Associated With Cervical Spine and Postural Disorders박진영No ratings yet

- No. 44. Neural Tube DefectsDocument11 pagesNo. 44. Neural Tube DefectsenriqueNo ratings yet

- Congenital Eventration of The Diaphragm+++Document13 pagesCongenital Eventration of The Diaphragm+++TommyNo ratings yet

- Correos Electrónicos 1-S2.0-S0733861911000879-MainDocument25 pagesCorreos Electrónicos 1-S2.0-S0733861911000879-Mainjcr87No ratings yet

- Diaphragmatic Ultrasound - A Review of Its Methodological Aspects and Clinical UsesDocument17 pagesDiaphragmatic Ultrasound - A Review of Its Methodological Aspects and Clinical Usesdr.osamahalwalidNo ratings yet

- Diaphragmatic Eventration Review of Current Knowledge Diagnostic and Management OptionsDocument4 pagesDiaphragmatic Eventration Review of Current Knowledge Diagnostic and Management OptionsDwi AryanataNo ratings yet

- Peroneal Nerve Palsy PDFDocument10 pagesPeroneal Nerve Palsy PDFChristian Reza WibowoNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Respiratory Disease in Dogs and Cats Diaphragmatic HerniaDocument9 pagesTextbook of Respiratory Disease in Dogs and Cats Diaphragmatic HerniaDiego CushicóndorNo ratings yet

- Imaging in DiaphragmaDocument12 pagesImaging in DiaphragmahendrayatiranyNo ratings yet

- Horner's SyndromeDocument7 pagesHorner's SyndromeNastiti WidyariniNo ratings yet

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Devin K. Binder, M.D., PH.D, Meic H. Schmidt, M.D., and Philip R. Weinstein, M.DDocument10 pagesLumbar Spinal Stenosis: Devin K. Binder, M.D., PH.D, Meic H. Schmidt, M.D., and Philip R. Weinstein, M.DYerni DaeliNo ratings yet

- 694.full Neurogenic DysphafgiaDocument6 pages694.full Neurogenic DysphafgiaarifNo ratings yet

- Duane SyndromeDocument1 pageDuane SyndromemoresubscriptionsNo ratings yet

- 1244 2260 1 SMDocument3 pages1244 2260 1 SMHeru Sutanto KNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoDocument5 pagesEvaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoFranciscoJ.ReynaSepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- 2011 32 109 Holly A. Zywicke and Curtis J. Rozzelle: Pediatrics in ReviewDocument10 pages2011 32 109 Holly A. Zywicke and Curtis J. Rozzelle: Pediatrics in ReviewNavine NalechamiNo ratings yet

- SHOULDER INSTABILITY ManagDocument18 pagesSHOULDER INSTABILITY ManagFarhan JustisiaNo ratings yet

- Airway Assessment Predictors of Difficult AirwayDocument7 pagesAirway Assessment Predictors of Difficult AirwayChakib AmariNo ratings yet

- Instructional Course Lectures: SelectedDocument10 pagesInstructional Course Lectures: SelectedStephen JamesNo ratings yet

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Overview On Features, Diagnosis & Orthodontic ManagementDocument6 pagesObstructive Sleep Apnea: An Overview On Features, Diagnosis & Orthodontic Managementsajida khanNo ratings yet

- LD Disease I J AnaesthDocument3 pagesLD Disease I J Anaesthkrishan bansalNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis of SpineDocument11 pagesTuberculosis of SpineSepti RahadianNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoDocument5 pagesEvaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoFranciscoJ.ReynaSepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- DDMSDocument5 pagesDDMSaghniajolandaNo ratings yet

- Diaphragmaticpacingin Spinalcordinjury: Kevin Dalal,, Anthony F. DimarcoDocument11 pagesDiaphragmaticpacingin Spinalcordinjury: Kevin Dalal,, Anthony F. DimarcoRatna HidayatiNo ratings yet

- RehabDocument21 pagesRehabSalma AfifiNo ratings yet

- Spina Biphida. N Engl J Med 2022Document7 pagesSpina Biphida. N Engl J Med 2022JUAN GUAPO MENDOZANo ratings yet

- DVT CaseDocument4 pagesDVT CaseJelcy MangulabnanNo ratings yet

- Articulo de EstrabismoDocument7 pagesArticulo de EstrabismoJohana DíazNo ratings yet

- Atualização NeuromuscularDocument5 pagesAtualização NeuromuscularRodrigo VanzelliNo ratings yet

- Chest Wall Deformities by Atrey GaonkarDocument48 pagesChest Wall Deformities by Atrey GaonkaratreygaonkarNo ratings yet

- Atrial Septal Defect - 7 Year OldDocument1 pageAtrial Septal Defect - 7 Year OldMSNo ratings yet

- Bedside Water Swallow Test ArticleDocument4 pagesBedside Water Swallow Test ArticleJU WSDNo ratings yet

- AtelektasisDocument10 pagesAtelektasisSaputri AnggiNo ratings yet

- Bench-To-bedside Review Delirium in ICU Patients - Importance of Sleep DeprivationDocument8 pagesBench-To-bedside Review Delirium in ICU Patients - Importance of Sleep DeprivationTai rascunhos TaiNo ratings yet

- Management of The Traumatized AirwayDocument8 pagesManagement of The Traumatized AirwayAnonymous h0DxuJTNo ratings yet

- BedahDocument7 pagesBedahSandy Pensi HuntingNo ratings yet

- RCCM 200204-270ccDocument5 pagesRCCM 200204-270ccJunior BarretoNo ratings yet

- Respiratorymuscle Assessmentinclinical Practice: Michael I. PolkeyDocument9 pagesRespiratorymuscle Assessmentinclinical Practice: Michael I. PolkeyanaNo ratings yet

- Duane SyndromeDocument27 pagesDuane SyndromeAlphamaleagainNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia in ElderlyDocument16 pagesAnaesthesia in ElderlySasi RadinaNo ratings yet

- Diaphragm Paralysis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandDiaphragm Paralysis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 15 04700Document12 pagesNutrients 15 04700Fabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- Key Principles For Scientific PublishingDocument6 pagesKey Principles For Scientific PublishingFabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- ISSN CentreDocument5 pagesISSN CentreFabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 00106 v2Document19 pagesNutrients 13 00106 v2Fabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0531556523000700 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0531556523000700 MainFabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- Consent Advice Laparoscopic Tubal OcclusionDocument2 pagesConsent Advice Laparoscopic Tubal OcclusionKathJamesNo ratings yet

- Checklist For CvaDocument2 pagesChecklist For CvaCamille Neypes CarreraNo ratings yet

- Nle Practice Test CDocument12 pagesNle Practice Test CAr-jay JubaneNo ratings yet

- Case Taking in HomeopathyDocument19 pagesCase Taking in Homeopathymiadelfior100% (2)

- Hesi Med Surg Study GuideDocument1 pageHesi Med Surg Study GuideGeorge0% (1)

- Skills Math WorksheetDocument4 pagesSkills Math WorksheetBrennan MaguireNo ratings yet

- Hyponatremia in Tuberculous MeningitisDocument11 pagesHyponatremia in Tuberculous MeningitisBelinda Putri agustiaNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Validity of Psychiatric DiagnosisDocument74 pagesReliability and Validity of Psychiatric DiagnosisSarin DominicNo ratings yet

- Rachmat Belgi Saputra - 010.06.005 - New Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) Adjustment For Survival Prediction - Journal DR DudutDocument6 pagesRachmat Belgi Saputra - 010.06.005 - New Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) Adjustment For Survival Prediction - Journal DR DudutRachmat B SaputraNo ratings yet

- Tooth MobilityDocument47 pagesTooth Mobilityc4rm3LNo ratings yet

- E-Catalog - Nanjing Superstar Medical Co.,Ltd-2024Document18 pagesE-Catalog - Nanjing Superstar Medical Co.,Ltd-2024Muhammad WajidNo ratings yet

- Bantolinao, Liezl Dawn Entuna 2246018715Document2 pagesBantolinao, Liezl Dawn Entuna 2246018715shyNo ratings yet

- OSNA For Lymph Node Analysis in Breast Cancer: One Step - One DecisionDocument8 pagesOSNA For Lymph Node Analysis in Breast Cancer: One Step - One DecisionStacey Lee100% (1)

- Case Study LRTIDocument18 pagesCase Study LRTINorman DyantoNo ratings yet

- Miscellaneous: Eye, Ear, Skin, Pulmonary, Anti-Inflammatories & CancersDocument19 pagesMiscellaneous: Eye, Ear, Skin, Pulmonary, Anti-Inflammatories & CancersAbobakr AlobeidNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography and ReflectionDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography and ReflectionwacraellaNo ratings yet

- Urinary Catheterization PPT LectureDocument43 pagesUrinary Catheterization PPT LectureSusan MaglaquiNo ratings yet

- Report Text About Covid 19Document4 pagesReport Text About Covid 19Yanti Sinaga100% (2)

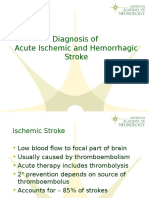

- Diagnosis of Acute Ischemic and Hemorrhagic StrokeDocument22 pagesDiagnosis of Acute Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Strokeyulian100% (2)

- 8.15.18 Welby TENS EMS and Massage Device - User ManualDocument129 pages8.15.18 Welby TENS EMS and Massage Device - User ManualPaula ComsaNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Applications of BiostatisticsDocument9 pagesIntroduction and Applications of BiostatisticsChaitali Dongaonkar ChawareNo ratings yet

- 559 1 2509 3 10 20211201Document4 pages559 1 2509 3 10 20211201Asrock 1No ratings yet

- Borderline Personality DisorderDocument4 pagesBorderline Personality DisorderColeen gaboyNo ratings yet

- Papich, Mark G. - Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs - Bisoprolol Fumarate (2016, Elsevier) (10.1016 - B978-0-323-24485-5.00107-8) - Libgen - LiDocument2 pagesPapich, Mark G. - Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs - Bisoprolol Fumarate (2016, Elsevier) (10.1016 - B978-0-323-24485-5.00107-8) - Libgen - LibernadethNo ratings yet

- Cara Christ Resignation PetitionDocument26 pagesCara Christ Resignation PetitionJoshua MoralesNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure in ChildrenDocument27 pagesHeart Failure in ChildrendenakarinaNo ratings yet

- Registered Members (Mumbai) - JainDocument72 pagesRegistered Members (Mumbai) - JainRohit Mishra100% (1)

10.1056NEJMra1007236

10.1056NEJMra1007236

Uploaded by

Fabià Pla ConsuegraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

10.1056NEJMra1007236

10.1056NEJMra1007236

Uploaded by

Fabià Pla ConsuegraCopyright:

Available Formats

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

Review article

Current Concepts

Dysfunction of the Diaphragm

F. Dennis McCool, M.D., and George E. Tzelepis, M.D.

T

From the Department of Pulmonary, Criti- he diaphragm is the dome-shaped structure that separates the

cal Care, and Sleep Medicine, Memorial thoracic and abdominal cavities. It is the principal muscle of respiration, is

Hospital of Rhode Island, Pawtucket

(F.D.M.); the Warren Alpert Medical innervated by the phrenic nerves that arise from the nerve roots at C3 through

School of Brown University, Providence, C5, and is primarily composed of fatigue-resistant slow-twitch type I and fast-twitch

RI (F.D.M.); and the Department of Patho- type IIa myofibers.1 Its mechanical action is best understood by considering its anat-

physiology, University of Athens Medical

School, Athens (G.E.T.). Address reprint omy and its attachment to the chest wall.2 The diaphragm abuts the lower rib cage

requests to Dr. McCool at the Department in a region referred to as the zone of apposition (Fig. 1). As the diaphragm contracts,

of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep the abdominal contents are displaced caudally, abdominal pressure increases in the

Medicine, Memorial Hospital of Rhode

Island, 111 Brewster St., Pawtucket, RI zone of apposition, and the lower rib cage expands. Disease processes that interfere

02860, or at f_mccool@brown.edu. with diaphragmatic innervation, contractile properties, or mechanical coupling to the

chest wall can result in diaphragmatic dysfunction.3 Such dysfunction, in turn, can

This article (10.1056/NEJMra1007236) was

updated on May 31, 2012, at NEJM.org. lead to dyspnea, decreased exercise performance, sleep-disordered breathing, consti-

tutional symptoms, hypersomnia, reduced quality of life, atelectasis, and respiratory

N Engl J Med 2012;366:932-42. failure.4-6 This review focuses on dysfunction related to weakness and paralysis, not to

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society.

anatomical abnormalities.

Cl inic a l Fe at ur e s

Diaphragmatic dysfunction is an underdiagnosed cause of dyspnea and should always

be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained dyspnea.7-9 Dysfunction of

the diaphragm ranges from a partial loss of the ability to generate pressure (weakness)

to a complete loss of diaphragmatic function (paralysis).6,10 Diaphragmatic weakness

or paralysis can involve either one or both hemidiaphragms and may be seen in the

context of metabolic or inflammatory disorders, after trauma or surgery, during me-

chanical ventilation, and with mediastinal masses, myopathies, neuropathies, or dis-

eases that cause lung hyperinflation.3,4,6,11-14

Patients with unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis are usually asymptomatic but may

have dyspnea on exertion and limited ability to exercise (Table 1).5,14-16 Occasionally,

patients with unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis report dyspnea when they are su-

pine. Coexisting conditions such as obesity, weakness of other muscle groups, or

underlying heart and lung disease (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) may

worsen dyspnea in patients with unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, especially when

they are supine.17 If patients have no symptoms, unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis

may be discovered as an incidental radiographic finding of an elevated hemidia-

phragm.

Patients with bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis or severe diaphragmatic weakness

are more likely to have symptoms and may present with unexplained dyspnea or recur-

rent respiratory failure. They can have considerable dyspnea at rest, when supine,

with exertion, or when immersed in water above their waist.4,8 They often need to use

a recliner for sleep and to avoid swimming or activities that require bending.3 A

history of chest surgery, manipulation of the cervical spine, neck injury, a slowly pro-

932 n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Current Concepts

gressive neuromuscular disease, or acute neck or

shoulder pain should be sought in patients with

either unilateral or bilateral diaphragmatic paraly-

sis.4 Patients with bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis

are at an increased risk for sleep fragmentation

and hypoventilation during sleep.18,19 Consequent-

ly, initial symptoms may include fatigue, hyper-

somnia, depression, morning headaches, and fre-

quent nocturnal awakenings. Other complications

of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis include sub-

segmental atelectasis and infections of the lower

respiratory tract.

On examination, tachypnea and use of acces-

sory muscles may be noted during quiet breath-

ing.4 The use of accessory muscles can be recog-

nized by palpating the neck; the examiner can

sense contraction of the sternocleidomastoid mus-

cles during inspiratory efforts. Decreased dia-

phragmatic excursion may be detected by percus-

sion of the lower rib cage at end expiration and end

inspiration. The most characteristic physical sign

of diaphragmatic dysfunction is abdominal para-

dox, which is the paradoxical inward motion of

the abdomen as the rib cage expands during Figure 1. Anatomical Arrangement of the Diaphragm with the Rib Cage

and Abdomen.

inspiration (Fig. 2).4,20 This disordered breathing

The cylindrical region of the diaphragm that apposes the lower rib cage is

pattern results from compensatory use of the ac-

referred to as the zone of apposition of the diaphragm.

cessory inspiratory muscles of the rib cage and

neck.15,21 When these muscles contract and lower

pleural pressure, the weakened or flaccid dia- diaphragmatic dysfunction is progressive, where-

phragm moves in a cephalad direction and the as in the case of post-traumatic or infectious dia-

abdominal wall moves inward. This paradoxical phragmatic paralysis, spontaneous recovery occurs

breathing pattern is most easily seen with the pa- in approximately two thirds of patients but may

tient in the supine position. Abdominal paradox take a considerable amount of time.12,13,22-25 Re-

is typically observed when the maximum trans- generation of the phrenic nerve, which may take

diaphragmatic pressure that the patient can up to 3 years, is necessary for recovery.13 Patients

generate against a closed airway is less than 30 cm with unilateral or bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis

of water10; it rarely occurs in unilateral diaphrag-that is due to neuralgic amyotrophy (often marked

matic paralysis.16,17 When abdominal paradox is by a history of acute shoulder or neck pain followed

present in unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, it by dyspnea) typically have complete recovery or

suggests generalized weakness of the respiratory improvement in symptoms in 1 to 1.5 years.13,24

muscles.16 Recovery times may be somewhat shorter in pa-

tients who have diaphragmatic dysfunction after

Nat ur a l His t or y cardiac surgery.12 In contrast, the prognosis is poor

for patients who have diaphragmatic dysfunction

The natural history of diaphragmatic dysfunction after traumatic injury to the spinal cord.23

depends largely on its cause and the rate of pro-

gression of the underlying disease. Age-related C ause s

changes in respiratory drive, respiratory-muscle

strength, and chest-wall compliance may predis- The incidence of clinically significant diaphrag-

pose patients with diaphragmatic dysfunction to matic dysfunction is difficult to estimate, given its

hypoventilation.18-20 In certain neuromuscular dis- multiple causes.3,4 The causes of diaphragmatic

eases (e.g., muscular dystrophies), the course of dysfunction can be classified by the level of the

n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012 933

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

Table 1. Comparison of Bilateral and Unilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis.*

Diagnostic Tools and Treatment Bilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis Unilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis

Presentation Dyspnea at rest, unexplained dyspnea, exer- Asymptomatic, unexplained dyspnea; exer-

cise limitation, orthopnea, dyspnea when cise limitation, incidental radiographic

bending, constitutional symptoms, dys- finding

pnea when entering water, respiratory

failure, prolonged mechanical ventilation

History Neck or shoulder pain, chest or neck surgery, Neck or shoulder pain, chest or neck surgery,

neck injury, manipulation of the cervical neck injury, manipulation of the cervical

spine, neuromuscular disease spine, neuromuscular disease

Examination Abdominal paradox No abdominal paradox

Laboratory tests

Vital capacity (% of predicted value) <50 >70

Decline in supine vital capacity (%) 30–50 10–30

MIP (% of predicted value) <30 >60

Fluoroscopy Not helpful Sniff test positive

Thickening of diaphragm on inspiration† No change No change

Pdi max (cm of water) <40 >70

Twitch Pdi (cm of water) <20 <10

Complications Frequent hypoventilation during sleep, atel- Occasional hypoventilation during sleep,

ectasis, pneumonia, respiratory failure atelectasis

Treatment

Observation period for recovery (yr) 1.5–3 1.5–3

Treatment for coexisting conditions Yes Yes

Reversal of metabolic disturbance Yes Yes

NIPPV Often indicated Usually not indicated

Plication of diaphragm Not indicated May be helpful

Phrenic pacing Yes, in patients with high SCI No

* MIP denotes maximal static inspiratory pressure, NIPPV noninvasive positive pressure ventilation, Pdi transdiaphragmatic pressure, Pdi max

maximal inspiratory efforts against a closed glottis, SCI spinal cord injury, and twitch Pdi transcutaneous electrical or magnetic stimulation

of the phrenic nerve.

† Changes in thickness of the diaphragm are measured with the use of ultrasonography of the diaphragmatic zone of apposition.

impairment and are discussed here in a rostral-to- as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or poliomyelitis,

caudal sequence (Fig. 3). With some disorders, often lead to diaphragmatic dysfunction and respi-

impairment may occur at more than one anatomi- ratory failure. Diaphragmatic weakness may occur

cal level; for example, critical illness polyneurop- shortly after or many years after the initial polio-

athy may be due to both a peripheral neuropathy myelitis infection (mean, 35 years).29 Other dis-

and myopathy.26 eases that cause diaphragmatic weakness and in-

The medulla or spinal cord may be affected by volve spinal motor neurons include syringomyelia,

demyelinating plaques. However, diaphragmatic paraneoplastic motor neuropathies (e.g., the anti-

weakness is infrequently found in multiple sclero- Hu syndrome), and spinal muscular atrophies.

sis.27 High spinal cord injuries (at C1 or C2) result Respiratory failure accounts for most of the com-

in diaphragmatic paralysis, whereas diaphragmatic plications and deaths caused by these disorders.

function is partially preserved with midcervical le- Damage to the phrenic nerve is most com-

sions (at C3 through C5). About 40% of patients monly due to iatrogenic injury during surgery or

with lesions at C3 require mechanical ventilation, to compression caused by bronchogenic or medi-

whereas less than 15% of patients with lesions at astinal tumors.30,31 During cardiothoracic or neck

C4 or C5 need ventilatory support.28 Diseases in- surgery, damage of the phrenic nerve may be due

volving the lower motor neurons in the spine, such to transection, stretching, crushing, or hypother-

934 n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Current Concepts

A Normal

B Paralyzed

Figure 2. Comparison of Rib-Cage and Abdominal Motion in Normal and Paralyzed Diaphragms.

Panel A shows how normal diaphragmatic contraction results in an outward motion of the abdomen and rib cage

(arrows). Panel B shows how diaphragmatic paralysis results in a paradoxical inward motion of the abdomen (down-

ward-pointing arrow) during inspiration. The accessory inspiratory muscles contract, lifting the rib cage (upward-

pointing arrow) and lowering the intrathoracic pressure. This change causes the flaccid diaphragm to move in a

cephalad direction and the anterior abdominal wall to move inward.

mia. In cardiac surgery, the use of cold saline myasthenic crisis, requires ventilatory support, and

solutions containing ice chips or slush to lower usually responds to immunomodulating therapy.3

myocardial temperature is the most important Diaphragmatic dysfunction is not commonly seen

risk factor for phrenic-nerve injury.32 The avoidance in the Lambert–Eaton syndrome.38 Botulinum tox-

of hypothermic injury to the phrenic nerve with the ins (most often type A) impair diaphragmatic func-

use of cardiac insulation pads has significantly tion by interfering with the release of acetylcholine

decreased the incidence of diaphragmatic dysfunc- into the neuromuscular junction.39 In rare cases,

tion in these patients.33 Other processes that can medications, such as aminoglycosides, interfere

directly involve the phrenic nerve include trauma, with neuromuscular transmission, causing dia-

infections (e.g., herpes zoster and Lyme disease), phragmatic weakness and respiratory failure. Vari-

and inflammatory disorders. The Guillain–Barré ous inherited or acquired myopathies may impair

syndrome is often complicated by phrenic-nerve diaphragmatic function and lead to respiratory

involvement, with up to 25% of patients requiring failure early in life or in adulthood.3,4

mechanical ventilation.34,35 The phrenic nerve may Critical-illness polyneuropathy and myopathy

be involved in approximately 5% of patients are common causes of diaphragmatic weakness

with neuralgic amyotrophy (Parsonage–Turner syn- and ventilator dependency in patients in the in-

drome) and in up to 2% of patients who have un- tensive care unit.26 They are more common among

dergone cardiac surgery.25,36,37 patients with sepsis, multiorgan failure, and hyper-

Disordered synaptic transmission at the neuro- glycemia and should be considered in patients for

muscular junction may be manifested as diaphrag- whom weaning from ventilator support is diffi-

matic dysfunction.3,10,38 In myasthenia gravis, cult.26 Disuse atrophy of the diaphragm can occur

acute respiratory failure most often occurs during even after brief periods of mechanical ventilation

n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012 935

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

Multiple sclerosis

Stroke

Arnold–Chiari malformation

Quadriplegia

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Poliomyelitis

Spinal muscular atrophy

Syringomyelia

Phrenic

Guillain–Barré syndrome nerve

Tumor compression

Neuralgic neuropathy

Critical-illness polyneuropathy

Chronic inflammatory

demyelinating polyneuropathy

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease

Idiopathic

Hyperinflation (COPD, asthma)

Myasthenia gravis

Lambert–Eaton syndrome

Botulism

Organophosphates

Drugs

Muscular dystrophies

Myositis (infectious,

inflammatory, metabolic)

Diaphragm

Acid maltase deficiency

Glucocorticoids

Disuse atrophy

Figure 3. Causes of Diaphragmatic Dysfunction, According to Level of Impairment.

Disorders that occur at various regions in the body can lead to diaphragmatic dysfunction. COPD denotes chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease.

or after the administration of paralyzing agents; it mia, and thyroid disturbances can contribute to

is associated with atrophy of both fast-twitch and diaphragmatic dysfunction and prolong ventilator

slow-twitch myofibers.40-42 Undernutrition and dependency.43,44 The combination of diaphrag-

metabolic abnormalities such as hypophosphate- matic weakness and any process that increases the

mia, hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia, hypocalce- work of breathing (e.g., pneumonia, pulmonary

936 n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Current Concepts

edema, atelectasis, or bronchospasm) may over- phragm. This abrupt caudal motion at the onset of

whelm the capacity of even a mildly weakened dia- inspiration may be falsely interpreted as contraction

phragm and contribute to prolonged mechanical of the diaphragm.20

ventilation. Decisions about workup are generally made

Lung hyperinflation in chronic obstructive pul- on the basis of the invasiveness and availability

monary disease impairs diaphragmatic function by of testing (Fig. 4). Pulmonary-function tests,

shortening the diaphragm to a suboptimal length especially measurements of upright and supine

and, to a lesser extent, by impairing mechanical vital capacity, are readily available, are noninvasive,

advantage in the diaphragm (i.e., ineffective trans- and may support or refute the diagnosis of dia-

lation of diaphragmatic tension to transdiaphrag- phragmatic dysfunction. With unilateral dia-

matic pressure).3,45,46 Therapeutic interventions, phragmatic paralysis, total lung capacity may be

such as long-acting bronchodilators, surgery to mildly restricted (70 to 79% of the predicted

reduce lung volume, and lung transplantation, can value).10 In severe diaphragmatic weakness or

mitigate the negative effects of hyperinflation on bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, there is typi-

diaphragmatic function by promoting lung emp- cally moderate-to-severe restriction (30 to 50%

tying and decreasing lung volume, thereby improv- of the predicted value for total lung capacity). In

ing the length and contractility of the dia- both unilateral and bilateral diaphragmatic pa-

phragm.47-49 ralysis, the restrictive dysfunction becomes more

severe when the patient is in the supine position. A

Di agnosis decrease in vital capacity of 30 to 50% when the

patient is supine supports the diagnosis of bilat-

Once suspected, diaphragmatic dysfunction can be eral diaphragmatic paralysis, whereas a decrease

confirmed by a number of tests. Chest radiographs in vital capacity of 10 to 30% of the vital capac-

may reveal elevated hemidiaphragms and basal ity when the patient is seated may be seen with

subsegmental atelectasis.4 However, elevation of mild diaphragmatic weakness or unilateral dia-

both hemidiaphragms, as is commonly seen in pa- phragmatic paralysis.14,21 When there is little or

tients who are ventilator-dependent, may be inter- no reduction in supine vital capacity, the presence

preted as a “poor inspiratory effort” or “low lung of clinically significant diaphragmatic weakness

volumes” and has low specificity for diagnosing is unlikely.10 The mechanism related to the re-

diaphragmatic dysfunction.50 Although chest radi- duction in supine vital capacity is the cephalad

ography is a reasonably sensitive tool for detecting displacement of abdominal contents in concert

unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis (90%), its spec- with ineffective activity of the accessory inspira-

ificity is unacceptably low (44%).50 tory muscles.14,21 The functional residual capacity

Fluoroscopy of the diaphragm has been exten- and residual volume are usually normal in pa-

sively used to evaluate diaphragmatic function. A tients with unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis and

“sniff test” consists of assessing the motion of the are decreased in those with bilateral diaphrag-

diaphragm during a short, sharp inspiratory effort matic paralysis.14,21

through the nostrils. Descent of the diaphragm Two additional measures of diaphragmatic

will be seen in persons without the disorder. With strength are maximal static inspiratory pressure

unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis, there is a para- and sniff nasal inspiratory pressure. These mea-

doxical (cephalad) movement of the paralyzed surements are also noninvasive but are effort-

hemidiaphragm. Although the sniff test may be dependent and more variable than measurements

used to diagnose unilateral diaphragmatic paraly- of lung volume.52,53 Maximal static inspiratory

sis, it is no longer considered a helpful test in di- pressure and sniff nasal inspiratory pressure are

agnosing bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis.3 False mildly reduced, to about 60% of the predicted

positive results of the sniff test may occur in as value, in patients with unilateral diaphragmatic

many as 6% of patients without diaphragmatic paralysis and are markedly reduced, to less than

paralysis.51 False negative results can occur with 30% of the predicted value, in those with bilateral

active contraction of the abdominal muscles dur- diaphragmatic paralysis.14,21 Maximal expiratory

ing expiration to volumes below functional residu- pressure is typically preserved in patients with

al capacity, followed by abrupt relaxation of the disease processes that affect the diaphragm but

abdominal muscles at the onset of inspiration, spare the expiratory muscles. Concomitant reduc-

resulting in caudal motion of the paralyzed dia- tions in maximal static inspiratory pressure and in

n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012 937

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

max), or transcutaneous electrical or magnetic

Normal vital capacity stimulation of the phrenic nerve (twitch Pdi). A

and sniff Pdi or Pdi max greater than 80 cm of water

<20% drop in supine vital capacity

in men and greater than 70 cm of water in wom-

No Yes en rules out clinically significant diaphragmatic

weakness.52,53 A twitch Pdi greater than 10 cm of

Maximal inspiratory pressure water with unilateral phrenic-nerve stimulation

>80 cm of water (men)

>70 cm of water (women) or greater than 20 cm of water with bilateral

Bilateral diaphragmatic

or

Underwent randomization Yes

paralysis unlikely phrenic-nerve stimulation also rules out clinically

Sniff negative inspiratory pressure

>70 cm of water (men) significant weakness.53 Twitch Pdi is a useful

>60 cm of water (women) means of assessing diaphragmatic function in

cases in which there is an inability to perform the

No

Yes maneuvers required for the other Pdi tests or sepa-

rate evaluation of each hemidiaphragm is neces-

Special Tests

sary.53 Although measurement of Pdi is generally

Ultrasonography considered the standard for establishing the diag-

Diaphragmatic thickness >2 mm and

thickening >20% with inspiration Bilateral diaphragmatic nosis of bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis,14,20,54

No

or paralysis present the tests are invasive and uncomfortable.

Transdiaphragmatic pressure Ultrasonography of the diaphragm at its zone of

Pdi max, >40 cm of water

Twitch Pdi, >20 cm of water apposition with the rib cage is a noninvasive tech-

nique that can be used to measure changes in the

Figure 4. Diagnostic Algorithm for Bilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis.

thickness of the diaphragm during inspiration

This flowchart shows the diagnostic tests that are useful in evaluating

(Fig. 5; and Video 1, available at NEJM.org). Thick-

whether a patient has bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. Pdi denotes trans- ening of the diaphragm reflects diaphragmatic

diaphragmatic pressure, Pdi max a Pdi measured during maximal inspiratory shortening,55 and a lack of thickening with inspira-

efforts against a closed glottis, and twitch Pdi a Pdi measured with transcu- tion is diagnostic of diaphragmatic paralysis (Vid-

taneous electrical or magnetic stimulation of the phrenic nerve. eo 2).56 Because ultrasonography can distinguish a

functioning from a nonfunctioning diaphragm, it

maximal expiratory pressure suggest that the can be used to diagnose both unilateral and bilat-

cause of the diaphragmatic dysfunction is a gener- eral diaphragmatic paralysis and to monitor recov-

alized process involving both the inspiratory and ery of the paralyzed diaphragm.24,56 Ultrasonog-

expiratory muscles (e.g., muscular dystrophy).21,37 raphy of the diaphragmatic dome has also been

Videos showing However, a mild reduction in maximal expiratory reported as a method for documenting diaphrag-

ultrasonography pressure (70 to 80% of the predicted value) may matic paralysis in adults57,58 and children59; how-

of normal and simply reflect suboptimal length–tension proper- ever, this technique primarily images the central

paralyzed

diaphragms

ties of the expiratory muscles at a restricted total tendon of the diaphragm, not the muscular com-

are available at lung capacity, rather than a generalized myopathic ponent, and is subject to limitations similar to

NEJM.org process. those of fluoroscopy of the diaphragm.

Direct measures of diaphragmatic function can Electromyography of the diaphragm can be

be classified as invasive (e.g., transdiaphragmatic performed during quiet breathing or during stimu-

pressure [Pdi]) or noninvasive (e.g., ultrasonogra- lation of the phrenic nerve. Its role in the diagno-

phy). These tests may not be offered at some insti- sis of diaphragmatic paralysis or weakness is lim-

tutions but may be required when the diagnosis ited by a number of technical issues, including the

remains uncertain. Measurement of Pdi requires proper placement of electrodes, the possibility of

transnasal placement of balloon catheters in the electromyographic “cross-talk” from adjacent mus-

lower esophagus and stomach (Fig. 1 in the Sup- cles, and the variable distances between muscles

plementary Appendix, available with the full text of and electrodes that result from differences in

this article at NEJM.org). Pdi is calculated as the subcutaneous fat among patients.11,60 However,

difference between the gastric and esophageal electromyography of the diaphragm may be use-

pressures. It can be measured during tidal breath- ful in distinguishing between neuropathic and

ing, maximal sniff maneuvers (sniff Pdi), maximal myopathic causes of known diaphragmatic dys-

inspiratory efforts against a closed glottis (Pdi function.

938 n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Current Concepts

A B

Pleura

Chest Wall

Normal

Diaphragm

Diaphragm

Diaphragm

Lung

Peritoneum

Liver Liver

C D

Chest Wall Pleura

Pleura

Paralyzed

Diaphragm

m

hrag

m Diap

hrag

Diap

Peritoneum

Peritoneum

Lung Liver Lung

Figure 5. Ultrasonographic Images of Normal and Paralyzed Diaphragms.

Panels A and B show the end-expiration and end-inspiration stages, respectively, in a normal diaphragm. Panels C

and D show the end-expiration and end-inspiration stages, respectively, in a paralyzed diaphragm. During inspiration,

the normal diaphragm thickens, whereas the paralyzed diaphragm does not thicken.

T r e atmen t neuromuscular diseases. The generally accepted in-

dications for initiating nocturnal noninvasive venti-

The treatment of patients with diaphragmatic dys- lation in patients with symptoms include a partial

function depends on the cause and on the pres- pressure of carbon dioxide of 45 mm Hg or high-

ence or absence of symptoms and nocturnal hy- er in the arterial blood in the daytime, oxygen

poventilation. Examples of treatable causes of saturation of 88% or less for 5 consecutive min-

diaphragmatic dysfunction include myopathies re- utes at night, or progressive neuromuscular dis-

lated to metabolic disturbances such as hypoka- ease with a maximal static inspiratory pressure of

lemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, and hy- less than 60 cm of water or a forced vital capacity

pophosphatemia. Correction of electrolyte and of less than 50% of the predicted value.62 Most

hormonal imbalances and avoidance of neuro- patients with neuromuscular disease will eventu-

pathic or neuromuscular blocking agents can re- ally require mechanical ventilation, whether it is

store strength in the diaphragm. Myopathies due to provided by invasive means (tracheostomy or endo-

parasitic infection (e.g., trichinosis) may respond tracheal tube) or noninvasive means (nasal can-

to appropriate antimicrobial agents.61 Idiopathic nula or face mask).

diaphragmatic paralysis or paralysis due to neu- Plication of the diaphragm is a procedure in

ralgic amyotrophy may improve spontaneously.13 which the flaccid hemidiaphragm is made taut by

When diaphragmatic dysfunction persists or pro- oversewing the membranous central tendon and

gresses, ventilatory support, ranging from noctur- the muscular components of the diaphragm. The

nal to continuous, may be needed. The need for indications and timing for this procedure are not

ventilatory support may be temporary, as in cases fully defined, given that most studies are retro-

of diaphragmatic paralysis after cardiac surgery, or spective and uncontrolled, but it may be offered to

it may be permanent, as in cases of progressive patients with unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis

n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012 939

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

who have severe dyspnea, cough, or chest pain or patients with diaphragmatic dysfunction, since

who are ventilator-dependent.63 Plication of the suppression of the activity of accessory inspiratory

diaphragm may result in increases of up to 20% in muscles during rapid-eye-movement sleep leads to

vital capacity, forced expiratory volume in 1 sec- hypoventilation.17,70 In patients with severe dia-

ond, and total lung capacity, along with improve- phragmatic weakness or unilateral diaphragmatic

ment in dyspnea.63,64 The increase in lung volumes paralysis, sleep-disordered breathing develops in-

related to plication results from immobilization dependently of body-mass index, sex, and age.17

of the diaphragm, which lessens its paradoxical Among patients with unilateral diaphragmatic

motion.65 In general, a long period of observation paralysis, sleep-disordered breathing is primarily

should be considered before plication is recom- found in those with clinically significant weakness

mended. This is especially true for patients with (unilateral twitch Pdi, <5 cm of water).17 Patients

unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis after cardiac with diaphragmatic weakness that is due to a neu-

surgery or other surgical procedures that involve romuscular disease, such as muscular dystrophy or

the cervical or mediastinal regions, since phrenic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, may also have ob-

function may improve with time.12,24,66 Morbid structive sleep apnea. Weakness of pharyngeal and

obesity and progressive neuromuscular diseases laryngeal muscles may predispose these patients to

are relative contraindications to plication of the airway collapse during inspiration.70 As with other

diaphragm.67 Plication is unlikely to be helpful in causes of sleep-disordered breathing, noninvasive

bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis. positive-pressure ventilation is the preferred meth-

Phrenic pacing has the potential to provide full od of treatment for patients with diaphragmatic

ventilatory support for ventilator-dependent pa- paralysis because it can improve both symptoms

tients who have bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis and physiological derangements.

and intact phrenic nerves. Candidates for this An increase in the use of ultrasonography is

method of treatment are primarily patients with likely to lead to prompt identification of patients

high cervical cord quadriplegia or patients with with diaphragmatic dysfunction, and further in-

central hypoventilation. Despite technical improve- novations in noninvasive ventilation will lead to

ments in phrenic-pacing systems, activation of the more physiologic and comfortable ventilatory sup-

diaphragm does not provide sustained, full ven- port for these persons. Advances in intramuscular

tilatory support.68 Newer methods that use lapa- pacing and treatment of congenital myopathies

roscopic mapping of motor points and intramus- with enzyme-replacement or gene-transfer therapy

cular stimulation of the diaphragm have shown may provide further hope for effective treatment.

promising results.69 Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with

Sleep-disordered breathing is common among the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

1. Al-Bilbeisi F, McCool FD. Diaphragm 7. Davison A, Mulvey D. Idiopathic dia- phrenic nerve cold injury. Ann Thorac

recruitment during nonrespiratory activi- phragmatic weakness. BMJ 1992;304:492-4. Surg 1991;52:1005-8.

ties. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 8. McCool FD, Mead J. Dyspnea on im- 13. Hughes PD, Polkey MI, Moxham J,

162:456-9. mersion: mechanisms in patients with Green M. Long-term recovery of diaphragm

2. Loring SH, Mead J. Action of the dia- bilateral diaphragm paralysis. Am Rev strength in neuralgic amyotrophy. Eur

phragm on the rib cage inferred from a Respir Dis 1989;139:275-6. Respir J 1999;13:379-84.

force-balance analysis. J Appl Physiol 9. Mier AK, Brophy C, Green M. Out of 14. Laroche CM, Mier AK, Moxham J,

1982;53:756-60. depth, out of breath. Br Med J (Clin Res Green M. Diaphragm strength in patients

3. Laghi F, Tobin MJ. Disorders of the Ed) 1986;292:1495-6. with recent hemidiaphragm paralysis.

respiratory muscles. Am J Respir Crit Care 10. Mier-Jedrzejowicz A, Brophy C, Mox- Thorax 1988;43:170-4. [Erratum, Thorax

Med 2003;168:10-48. ham J, Green M. Assessment of dia- 1988;43:583.]

4. Gibson GJ. Diaphragmatic paresis: phragm weakness. Am Rev Respir Dis 15. Hart N, Nickol AH, Cramer D, et al.

pathophysiology, clinical features, and 1988;137:877-83. Effect of severe isolated unilateral and bi-

investigation. Thorax 1989;44:960-70. 11. Chan CK, Loke J, Virgulto JA, Mohs- lateral diaphragm weakness on exercise

5. Kumar N, Folger WN, Bolton CF. Dys- enin V, Ferranti R, Lammertse T. Bilateral performance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

pnea as the predominant manifestation diaphragmatic paralysis: clinical spectrum, 2002;165:1265-70.

of bilateral phrenic neuropathy. Mayo prognosis, and diagnostic approach. Arch 16. Lisboa C, Paré PD, Pertuzé J, et al. In-

Clin Proc 2004;79:1563-5. Phys Med Rehabil 1988;69:976-9. spiratory muscle function in unilateral

6. Wilcox PG, Pardy RL. Diaphragmatic 12. Efthimiou J, Butler J, Woodham C, diaphragmatic paralysis. Am Rev Respir

weakness and paralysis. Lung 1989;167: Benson MK, Westaby S. Diaphragm pa- Dis 1986;134:488-92.

323-41. ralysis following cardiac surgery: role of 17. Steier J, Jolley CJ, Seymour J, et al.

940 n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Current Concepts

Sleep-disordered breathing in unilateral 33. Wheeler WE, Rubis LJ, Jones CW, on diaphragm length in severe chronic

diaphragm paralysis or severe weakness. Harrah JD. Etiology and prevention of topi- obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J

Eur Respir J 2008;32:1479-87. cal cardiac hypothermia-induced phrenic Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:796-805.

18. Skatrud J, Iber C, McHugh W, Ras- nerve injury and left lower lobe atelectasis 49. O’Donnell DE. Hyperinflation, dys-

mussen H, Nichols D. Determinants of during cardiac surgery. Chest 1985;88: pnea, and exercise intolerance in chronic

hypoventilation during wakefulness and 680-3. obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am

sleep in diaphragmatic paralysis. Am Rev 34. Cosi V, Versino M. Guillain-Barré syn- Thorac Soc 2006;3:180-4.

Respir Dis 1980;121:587-93. drome. Neurol Sci 2006;27:Suppl 1:S47-S51. 50. Chetta A, Rehman AK, Moxham J, Carr

19. Stradling JR, Warley AR. Bilateral dia- 35. van Doorn PA, Ruts L, Jacobs BC. DH, Polkey MI. Chest radiography cannot

phragm paralysis and sleep apnoea with- Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treat- predict diaphragm function. Respir Med

out diurnal respiratory failure. Thorax 1988; ment of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet 2005;99:39-44.

43:75-7. Neurol 2008;7:939-50. 51. Alexander C. Diaphragm movements

20. Davis J, Goldman M, Loh L, Casson 36. Diehl JL, Lofaso F, Deleuze P, Similow and the diagnosis of diaphragmatic pa-

M. Diaphragm function and alveolar hy- ski T, Lemaire F, Brochard L. Clinically ralysis. Clin Radiol 1966;17:79-83.

poventilation. Q J Med 1976;45:87-100. relevant diaphragmatic dysfunction after 52. Polkey MI, Green M, Moxham J. Mea-

21. Laroche CM, Carroll N, Moxham J, cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc surement of respiratory muscle strength.

Green M. Clinical significance of severe Surg 1994;107:487-98. Thorax 1995;50:1131-5.

isolated diaphragm weakness. Am Rev 37. Mills GH, Kyroussis D, Hamnegard 53. Steier J, Kaul S, Seymour J, et al. The

Respir Dis 1988;138:862-6. CH, et al. Cervical magnetic stimulation value of multiple tests of respiratory mus-

22. Lahrmann H, Grisold W, Authier FJ, of the phrenic nerves in bilateral dia- cle strength. Thorax 2007;62:975-80.

Zifko UA. Neuralgic amyotrophy with phragm paralysis. Am J Respir Crit Care 54. Mier A, Brophy C, Moxham J, Green

phrenic nerve involvement. Muscle Nerve Med 1997;155:1565-9. M. Twitch pressures in the assessment of

1999;22:437-42. 38. Laroche CM, Mier AK, Spiro SG, New- diaphragm weakness. Thorax 1989;44:

23. Oo T, Watt JW, Soni BM, Sett PK. De- som-Davis J, Moxham J, Green M. Respi- 990-6.

layed diaphragm recovery in 12 patients ratory muscle weakness in the Lambert- 55. Cohn D, Benditt JO, Eveloff S, McCool

after high cervical spinal cord injury: a Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Thorax 1989; FD. Diaphragm thickening during inspi-

retrospective review of the diaphragm 44:913-8. ration. J Appl Physiol 1997;83:291-6.

status of 107 patients ventilated after 39. Witoonpanich R, Vichayanrat E, Tan- 56. Gottesman E, McCool FD. Ultrasound

acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1999; tisiriwit K, et al. Survival analysis for re- evaluation of the paralyzed diaphragm. Am

37:117-22. spiratory failure in patients with food- J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1570-4.

24. Summerhill EM, El-Sameed YA, Glid- borne botulism. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010; 57. Houston JG, Fleet M, Cowan MD, Mc-

den TJ, McCool FD. Monitoring recovery 48:177-83. Millan NC. Comparison of ultrasound

from diaphragm paralysis with ultra- 40. Jaber S, Petrof BJ, Jung B, et al. Rap- with fluoroscopy in the assessment of

sound. Chest 2008;133:737-43. idly progressive diaphragmatic weakness suspected hemidiaphragmatic movement

25. Tsairis P, Dyck PJ, Mulder DW. Natu- and injury during mechanical ventilation abnormality. Clin Radiol 1995;50:95-8.

ral history of brachial plexus neuropathy: in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 58. McCauley RG, Labib KB. Diaphrag-

report on 99 patients. Arch Neurol 1972; 2011;183:364-71. matic paralysis evaluated by phrenic nerve

27:109-17. 41. Levine S, Nguyen T, Taylor N, et al. stimulation during fluoroscopy or real-

26. Chawla J, Gruener G. Management of Rapid disuse atrophy of diaphragm fibers time ultrasound. Radiology 1984;153:33-6.

critical illness polyneuropathy and my- in mechanically ventilated humans. N Engl 59. Ambler R, Gruenewald S, John E. Ul-

opathy. Neurol Clin 2010;28:961-77. J Med 2008;358:1327-35. trasound monitoring of diaphragm activ-

27. Howard RS, Wiles CM, Hirsch NP, 42. Levine S, Budak MT, Dierov J, Singhal ity in bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis.

Loh L, Spencer GT, Newsom-Davis J. Re- S. Inactivity-induced diaphragm dysfunc- Arch Dis Child 1985;60:170-2.

spiratory involvement in multiple sclerosis. tion and mitochondria-targeted antioxi- 60. Saadeh PB, Crisafulli CF, Sosner J,

Brain 1992;115:479-94. dants: new concepts in critical care medi- Wolf E. Needle electromyography of the

28. Wicks AB, Menter RR. Long-term out- cine. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1844-5. diaphragm: a new technique. Muscle

look in quadriplegic patients with initial 43. Knochel JP. Neuromuscular manifes- Nerve 1993;16:15-20.

ventilator dependency. Chest 1986;90:406- tations of electrolyte disorders. Am J Med 61. Clausen MR, Meyer CN, Krantz T, et

10. 1982;72:521-35. al. Trichinella infection and clinical dis-

29. Dahan V, Kimoff RJ, Petrof BJ, Bene- 44. McParland C, Resch EF, Krishnan B, ease. QJM 1996;89:631-6.

detti A, Diorio D, Trojan DA. Sleep-disor- Wang Y, Cujec B, Gallagher CG. Inspira- 62. Clinical indications for noninvasive

dered breathing in fatigued postpoliomy- tory muscle weakness in chronic heart fail- positive pressure ventilation in chronic

elitis clinic patients. Arch Phys Med ure: role of nutrition and electrolyte status respiratory failure due to restrictive lung

Rehabil 2006;87:1352-6. and systemic myopathy. Am J Respir Crit disease, COPD, and nocturnal hypoventi-

30. Piehler JM, Pairolero PC, Gracey DR, Care Med 1995;151:1101-7. lation — a consensus conference report.

Bernatz PE. Unexplained diaphragmatic pa- 45. Decramer M. Effects of hyperinflation Chest 1999;116:521-34.

ralysis: a harbinger of malignant disease? on the respiratory muscles. Eur Respir 63. Freeman RK, Van Woerkom J, Vyver-

J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1982;84:861-4. J 1989;2:299-302. berg A, Ascioti AJ. Long-term follow-up of

31. Salati M, Cardillo G, Carbone L, et al. 46. Tzelepis G, McCool FD, Leith DE, the functional and physiologic results of

Iatrogenic phrenic nerve injury during thy- Hoppin FG Jr. Increased lung volume diaphragm plication in adults with uni-

mectomy: the extent of the problem. J Tho- limits endurance of inspiratory muscles. lateral diaphragm paralysis. Ann Thorac

rac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139(4):e77-e78. J Appl Physiol 1988;64:1796-802. Surg 2009;88:1112-7.

32. Merino-Ramirez MA, Juan G, Ramón 47. Estenne M. Effect of lung transplant 64. Mouroux J, Venissac N, Leo F, Alifano

M, et al. Electrophysiologic evaluation of and volume reduction surgery on respira- M, Guillot F. Surgical treatment of dia-

phrenic nerve and diaphragm function tory muscle function. J Appl Physiol 2009; phragmatic eventration using video-as-

after coronary bypass surgery: prospective 107:977-86. sisted thoracic surgery: a prospective

study of diabetes and other risk factors. 48. Lando Y, Boiselle PM, Shade D, et al. study. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:308-12.

J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:530-6. Effect of lung volume reduction surgery 65. Ciccolella DE, Daly BD, Celli BR. Im-

n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012 941

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.onNoSeptember

UNIVERSITY other uses10,

without

2013. permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Current Concepts

proved diaphragmatic function after sur- plication for eventration or paralysis: a ence in laparoscopic diaphragm pacing:

gical plication for unilateral diaphrag- review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg results and differences in spinal cord in-

matic paralysis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992; 2010;89:S2146-S2150. jured patients and amyotrophic lateral

146:797-9. 68. DiMarco AF, Kowalski KE. High-fre- sclerosis patients. Surg Endosc 2009;23:

66. Gayan-Ramirez G, Gosselin N, quency spinal cord stimulation of inspira- 1433-40.

Troosters T, Bruyninckx F, Gosselink R, tory muscles in dogs: a new method of 70. Bourke SC, Gibson GJ. Sleep and

Decramer M. Functional recovery of dia- inspiratory muscle pacing. J Appl Physiol breathing in neuromuscular disease. Eur

phragm paralysis: a long-term follow-up 2009;107:662-9. Respir J 2002;19:1194-201.

study. Respir Med 2008;102:690-8. 69. Onders RP, Elmo M, Khansarinia S, et Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society.

67. Groth SS, Andrade RS. Diaphragm al. Complete worldwide operative experi-

Brown Pelican Nigil Haroon, M.D.

942 n engl j med 366;10 nejm.org march 8, 2012

The New England Journal of Medicine

For personal

Downloaded from nejm.org at SIMON FRASER use only.on

UNIVERSITY NoSeptember

other uses10,

without

2013.permission.

For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Acls Cheat Sheet PDFDocument3 pagesAcls Cheat Sheet PDFDarren Dawkins100% (4)

- Crash Cart Check ListDocument2 pagesCrash Cart Check ListAnonymous iG0DCOfNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Disorders Care Plan Nursing Care PlanDocument4 pagesBipolar Disorders Care Plan Nursing Care PlanAnne de Vera0% (1)

- Diaphragm Plication For Eventration or Paralysis (A Review of The Literature)Document5 pagesDiaphragm Plication For Eventration or Paralysis (A Review of The Literature)TommyNo ratings yet

- S2531043718301624 PDFDocument13 pagesS2531043718301624 PDFAnja LjiljaNo ratings yet

- Diaphragmatic Dysfunction: ReviewDocument13 pagesDiaphragmatic Dysfunction: ReviewJuani CantellanosNo ratings yet

- diaphragmatic paralysisDocument10 pagesdiaphragmatic paralysismokhtarNo ratings yet

- Diseases of The Diaphragm, Chest Wall, Pleura, and MediastinumDocument16 pagesDiseases of The Diaphragm, Chest Wall, Pleura, and Mediastinumjpma2197No ratings yet

- Assessment of Respiratory Muscle Function StrengthDocument8 pagesAssessment of Respiratory Muscle Function StrengthsstavrosNo ratings yet

- Eventratio DiafragmaDocument9 pagesEventratio DiafragmairenaNo ratings yet

- Referensi 7 PDFDocument5 pagesReferensi 7 PDFirfhanahusaNo ratings yet

- 2 enDocument10 pages2 enRaj SinghNo ratings yet

- Difficult Airway Management in A Patient With AchondroplasiaDocument2 pagesDifficult Airway Management in A Patient With AchondroplasiaabdulmajeedNo ratings yet

- Locked-In Syndrome: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument6 pagesLocked-In Syndrome: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchsakuraleeshaoranNo ratings yet

- Disorders of The DiaphragmDocument16 pagesDisorders of The DiaphragmFajar YuniftiadiNo ratings yet

- The Upper Airway During Anaesthesia: D. R. Hillman, P. R. Platt and P. R. EastwoodDocument9 pagesThe Upper Airway During Anaesthesia: D. R. Hillman, P. R. Platt and P. R. EastwoodFendy PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia Management in Acute and Sub-Acute StrokeDocument10 pagesDysphagia Management in Acute and Sub-Acute Strokeprima trisna ajiNo ratings yet

- MedBack MyelomeningoceleDocument3 pagesMedBack MyelomeningoceleJulia Rei Eroles IlaganNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia For Prune Belly Syndrome: Syndromic Vignettes in AnaesthesiaDocument2 pagesAnaesthesia For Prune Belly Syndrome: Syndromic Vignettes in AnaesthesiaIonut BaraNo ratings yet

- Piis2212440318300592 PDFDocument3 pagesPiis2212440318300592 PDFUmer HussainNo ratings yet

- Duane SindromDocument5 pagesDuane SindromAlwin SoetandarNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia Associated With Cervical Spine and Postural DisordersDocument12 pagesDysphagia Associated With Cervical Spine and Postural Disorders박진영No ratings yet

- No. 44. Neural Tube DefectsDocument11 pagesNo. 44. Neural Tube DefectsenriqueNo ratings yet

- Congenital Eventration of The Diaphragm+++Document13 pagesCongenital Eventration of The Diaphragm+++TommyNo ratings yet

- Correos Electrónicos 1-S2.0-S0733861911000879-MainDocument25 pagesCorreos Electrónicos 1-S2.0-S0733861911000879-Mainjcr87No ratings yet

- Diaphragmatic Ultrasound - A Review of Its Methodological Aspects and Clinical UsesDocument17 pagesDiaphragmatic Ultrasound - A Review of Its Methodological Aspects and Clinical Usesdr.osamahalwalidNo ratings yet

- Diaphragmatic Eventration Review of Current Knowledge Diagnostic and Management OptionsDocument4 pagesDiaphragmatic Eventration Review of Current Knowledge Diagnostic and Management OptionsDwi AryanataNo ratings yet

- Peroneal Nerve Palsy PDFDocument10 pagesPeroneal Nerve Palsy PDFChristian Reza WibowoNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Respiratory Disease in Dogs and Cats Diaphragmatic HerniaDocument9 pagesTextbook of Respiratory Disease in Dogs and Cats Diaphragmatic HerniaDiego CushicóndorNo ratings yet

- Imaging in DiaphragmaDocument12 pagesImaging in DiaphragmahendrayatiranyNo ratings yet

- Horner's SyndromeDocument7 pagesHorner's SyndromeNastiti WidyariniNo ratings yet

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Devin K. Binder, M.D., PH.D, Meic H. Schmidt, M.D., and Philip R. Weinstein, M.DDocument10 pagesLumbar Spinal Stenosis: Devin K. Binder, M.D., PH.D, Meic H. Schmidt, M.D., and Philip R. Weinstein, M.DYerni DaeliNo ratings yet

- 694.full Neurogenic DysphafgiaDocument6 pages694.full Neurogenic DysphafgiaarifNo ratings yet

- Duane SyndromeDocument1 pageDuane SyndromemoresubscriptionsNo ratings yet

- 1244 2260 1 SMDocument3 pages1244 2260 1 SMHeru Sutanto KNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoDocument5 pagesEvaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoFranciscoJ.ReynaSepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- 2011 32 109 Holly A. Zywicke and Curtis J. Rozzelle: Pediatrics in ReviewDocument10 pages2011 32 109 Holly A. Zywicke and Curtis J. Rozzelle: Pediatrics in ReviewNavine NalechamiNo ratings yet

- SHOULDER INSTABILITY ManagDocument18 pagesSHOULDER INSTABILITY ManagFarhan JustisiaNo ratings yet

- Airway Assessment Predictors of Difficult AirwayDocument7 pagesAirway Assessment Predictors of Difficult AirwayChakib AmariNo ratings yet

- Instructional Course Lectures: SelectedDocument10 pagesInstructional Course Lectures: SelectedStephen JamesNo ratings yet

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea: An Overview On Features, Diagnosis & Orthodontic ManagementDocument6 pagesObstructive Sleep Apnea: An Overview On Features, Diagnosis & Orthodontic Managementsajida khanNo ratings yet

- LD Disease I J AnaesthDocument3 pagesLD Disease I J Anaesthkrishan bansalNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis of SpineDocument11 pagesTuberculosis of SpineSepti RahadianNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoDocument5 pagesEvaluation and Management of Elevated Diaphragm: Clemens Aigner Walter KlepetkoFranciscoJ.ReynaSepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- DDMSDocument5 pagesDDMSaghniajolandaNo ratings yet

- Diaphragmaticpacingin Spinalcordinjury: Kevin Dalal,, Anthony F. DimarcoDocument11 pagesDiaphragmaticpacingin Spinalcordinjury: Kevin Dalal,, Anthony F. DimarcoRatna HidayatiNo ratings yet

- RehabDocument21 pagesRehabSalma AfifiNo ratings yet

- Spina Biphida. N Engl J Med 2022Document7 pagesSpina Biphida. N Engl J Med 2022JUAN GUAPO MENDOZANo ratings yet

- DVT CaseDocument4 pagesDVT CaseJelcy MangulabnanNo ratings yet

- Articulo de EstrabismoDocument7 pagesArticulo de EstrabismoJohana DíazNo ratings yet

- Atualização NeuromuscularDocument5 pagesAtualização NeuromuscularRodrigo VanzelliNo ratings yet

- Chest Wall Deformities by Atrey GaonkarDocument48 pagesChest Wall Deformities by Atrey GaonkaratreygaonkarNo ratings yet

- Atrial Septal Defect - 7 Year OldDocument1 pageAtrial Septal Defect - 7 Year OldMSNo ratings yet

- Bedside Water Swallow Test ArticleDocument4 pagesBedside Water Swallow Test ArticleJU WSDNo ratings yet

- AtelektasisDocument10 pagesAtelektasisSaputri AnggiNo ratings yet

- Bench-To-bedside Review Delirium in ICU Patients - Importance of Sleep DeprivationDocument8 pagesBench-To-bedside Review Delirium in ICU Patients - Importance of Sleep DeprivationTai rascunhos TaiNo ratings yet

- Management of The Traumatized AirwayDocument8 pagesManagement of The Traumatized AirwayAnonymous h0DxuJTNo ratings yet

- BedahDocument7 pagesBedahSandy Pensi HuntingNo ratings yet

- RCCM 200204-270ccDocument5 pagesRCCM 200204-270ccJunior BarretoNo ratings yet

- Respiratorymuscle Assessmentinclinical Practice: Michael I. PolkeyDocument9 pagesRespiratorymuscle Assessmentinclinical Practice: Michael I. PolkeyanaNo ratings yet

- Duane SyndromeDocument27 pagesDuane SyndromeAlphamaleagainNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia in ElderlyDocument16 pagesAnaesthesia in ElderlySasi RadinaNo ratings yet

- Diaphragm Paralysis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandDiaphragm Paralysis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 15 04700Document12 pagesNutrients 15 04700Fabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- Key Principles For Scientific PublishingDocument6 pagesKey Principles For Scientific PublishingFabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- ISSN CentreDocument5 pagesISSN CentreFabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 00106 v2Document19 pagesNutrients 13 00106 v2Fabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0531556523000700 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0531556523000700 MainFabià Pla ConsuegraNo ratings yet

- Consent Advice Laparoscopic Tubal OcclusionDocument2 pagesConsent Advice Laparoscopic Tubal OcclusionKathJamesNo ratings yet

- Checklist For CvaDocument2 pagesChecklist For CvaCamille Neypes CarreraNo ratings yet

- Nle Practice Test CDocument12 pagesNle Practice Test CAr-jay JubaneNo ratings yet

- Case Taking in HomeopathyDocument19 pagesCase Taking in Homeopathymiadelfior100% (2)

- Hesi Med Surg Study GuideDocument1 pageHesi Med Surg Study GuideGeorge0% (1)

- Skills Math WorksheetDocument4 pagesSkills Math WorksheetBrennan MaguireNo ratings yet

- Hyponatremia in Tuberculous MeningitisDocument11 pagesHyponatremia in Tuberculous MeningitisBelinda Putri agustiaNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Validity of Psychiatric DiagnosisDocument74 pagesReliability and Validity of Psychiatric DiagnosisSarin DominicNo ratings yet

- Rachmat Belgi Saputra - 010.06.005 - New Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) Adjustment For Survival Prediction - Journal DR DudutDocument6 pagesRachmat Belgi Saputra - 010.06.005 - New Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) Adjustment For Survival Prediction - Journal DR DudutRachmat B SaputraNo ratings yet

- Tooth MobilityDocument47 pagesTooth Mobilityc4rm3LNo ratings yet

- E-Catalog - Nanjing Superstar Medical Co.,Ltd-2024Document18 pagesE-Catalog - Nanjing Superstar Medical Co.,Ltd-2024Muhammad WajidNo ratings yet

- Bantolinao, Liezl Dawn Entuna 2246018715Document2 pagesBantolinao, Liezl Dawn Entuna 2246018715shyNo ratings yet

- OSNA For Lymph Node Analysis in Breast Cancer: One Step - One DecisionDocument8 pagesOSNA For Lymph Node Analysis in Breast Cancer: One Step - One DecisionStacey Lee100% (1)

- Case Study LRTIDocument18 pagesCase Study LRTINorman DyantoNo ratings yet

- Miscellaneous: Eye, Ear, Skin, Pulmonary, Anti-Inflammatories & CancersDocument19 pagesMiscellaneous: Eye, Ear, Skin, Pulmonary, Anti-Inflammatories & CancersAbobakr AlobeidNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography and ReflectionDocument5 pagesAnnotated Bibliography and ReflectionwacraellaNo ratings yet

- Urinary Catheterization PPT LectureDocument43 pagesUrinary Catheterization PPT LectureSusan MaglaquiNo ratings yet

- Report Text About Covid 19Document4 pagesReport Text About Covid 19Yanti Sinaga100% (2)

- Diagnosis of Acute Ischemic and Hemorrhagic StrokeDocument22 pagesDiagnosis of Acute Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Strokeyulian100% (2)

- 8.15.18 Welby TENS EMS and Massage Device - User ManualDocument129 pages8.15.18 Welby TENS EMS and Massage Device - User ManualPaula ComsaNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Applications of BiostatisticsDocument9 pagesIntroduction and Applications of BiostatisticsChaitali Dongaonkar ChawareNo ratings yet

- 559 1 2509 3 10 20211201Document4 pages559 1 2509 3 10 20211201Asrock 1No ratings yet

- Borderline Personality DisorderDocument4 pagesBorderline Personality DisorderColeen gaboyNo ratings yet

- Papich, Mark G. - Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs - Bisoprolol Fumarate (2016, Elsevier) (10.1016 - B978-0-323-24485-5.00107-8) - Libgen - LiDocument2 pagesPapich, Mark G. - Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs - Bisoprolol Fumarate (2016, Elsevier) (10.1016 - B978-0-323-24485-5.00107-8) - Libgen - LibernadethNo ratings yet

- Cara Christ Resignation PetitionDocument26 pagesCara Christ Resignation PetitionJoshua MoralesNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure in ChildrenDocument27 pagesHeart Failure in ChildrendenakarinaNo ratings yet

- Registered Members (Mumbai) - JainDocument72 pagesRegistered Members (Mumbai) - JainRohit Mishra100% (1)