Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robinson-AccountingRelationEconomics-1909 (1)

Robinson-AccountingRelationEconomics-1909 (1)

Uploaded by

sandeepattigeri65Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Accounting Entry-Level TestDocument13 pagesAccounting Entry-Level TestQazi HammadNo ratings yet

- Economic Analysis For Business, Managerial Economics, MBA EconomicsDocument215 pagesEconomic Analysis For Business, Managerial Economics, MBA EconomicsSaravananSrvn90% (10)

- Blaine Kitchenware, Inc. - Capital Structure DATADocument5 pagesBlaine Kitchenware, Inc. - Capital Structure DATAShashank Gupta100% (1)

- Running Head: Financial Statement Analysis of Samsung 1Document19 pagesRunning Head: Financial Statement Analysis of Samsung 1Sangita GautamNo ratings yet

- Robinson AccountingRelationEconomics 1909Document14 pagesRobinson AccountingRelationEconomics 1909Dhruv SharmaNo ratings yet

- Suntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines London School of EconomicsDocument21 pagesSuntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines London School of EconomicsFelicia AprilianiNo ratings yet

- CoasefirmaDocument21 pagesCoasefirmaFernanda SennaNo ratings yet

- Accounting For LawyersDocument150 pagesAccounting For LawyersvivienkiigeNo ratings yet

- The Nature of FirmDocument21 pagesThe Nature of FirmMuhammad UsmanNo ratings yet

- Llewellyn, K. N. 1925. The Effect of Legal Institutions Upon Economics. The American Economic Review-2Document20 pagesLlewellyn, K. N. 1925. The Effect of Legal Institutions Upon Economics. The American Economic Review-2phngnguyn2706No ratings yet

- Contemporary Accting Res - 2021 - Hanlon - Behavioral Economics of Accounting A Review of Archival Research On IndividualDocument65 pagesContemporary Accting Res - 2021 - Hanlon - Behavioral Economics of Accounting A Review of Archival Research On IndividualNur Hidayah K FNo ratings yet

- Abegail Blanco Mm2-IDocument9 pagesAbegail Blanco Mm2-IAbegail BlancoNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Accountability From The For Itself To The For The Other 2002 Accounting, Organizations and SocietyDocument33 pagesEthics and Accountability From The For Itself To The For The Other 2002 Accounting, Organizations and SocietyiportobelloNo ratings yet

- Me Chapter OneDocument6 pagesMe Chapter OneSherefedin AdemNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument145 pagesEconomicsSaeed WataniNo ratings yet

- A Note On Welfare Propositions in EconomicsDocument13 pagesA Note On Welfare Propositions in EconomicsmkatsotisNo ratings yet

- Income 1925Document9 pagesIncome 1925Ayush SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Introduction To Economic TheoryDocument12 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction To Economic TheoryMaria Teresa Frando CahandingNo ratings yet

- Coase The Nature of The FirmDocument21 pagesCoase The Nature of The FirmMarcosNo ratings yet

- Ronald Coase - The Nature of The FirmDocument21 pagesRonald Coase - The Nature of The FirmIan BotelhoNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of Macro Economic Issues: Unit IDocument38 pagesNature and Scope of Macro Economic Issues: Unit IVig NeshNo ratings yet

- 1977, The Municipal Accounting Maze, An Analysis of Political Incentives, ZimmermanDocument39 pages1977, The Municipal Accounting Maze, An Analysis of Political Incentives, ZimmermanIrham PNo ratings yet

- Eco 3rd Sem Chapter 2Document10 pagesEco 3rd Sem Chapter 2Athul MNo ratings yet

- List of Basic Economic Problems and Their SolutionDocument3 pagesList of Basic Economic Problems and Their SolutionSheryl BorromeoNo ratings yet

- A M U, A: Ligarh Uslim Niversity LigarhDocument13 pagesA M U, A: Ligarh Uslim Niversity LigarhKajal SinghNo ratings yet

- Ecm Pro 071265Document61 pagesEcm Pro 071265Olivia FelNo ratings yet

- Basic Economics With LRTDocument4 pagesBasic Economics With LRTtrix catorceNo ratings yet

- Modern Economy - SS11Document18 pagesModern Economy - SS11Christine Joy MarcelNo ratings yet

- Economics I ProjectDocument14 pagesEconomics I ProjectGoldy SinghNo ratings yet

- Ecn 211 Lecture Note Moodle 1Document13 pagesEcn 211 Lecture Note Moodle 1AdaezeNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Definitions (Lesson 1) Basic MicroDocument10 pagesIntroduction and Definitions (Lesson 1) Basic MicroMark Laurenze MangaNo ratings yet

- Couse Name: Managerial Economics Course Code: MGMT4062 Unit 1: Basics of Managerial EconomicsDocument11 pagesCouse Name: Managerial Economics Course Code: MGMT4062 Unit 1: Basics of Managerial Economicskunal kashyapNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Principles of MicroeconomicsDocument3 pagesAssignment 3 Principles of MicroeconomicsChris MwaiNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDocument4 pagesBachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDave EscalaNo ratings yet

- Equity Theories Past Present and Future Carien Van Mourik 2010Document19 pagesEquity Theories Past Present and Future Carien Van Mourik 2010Firmansyah DjafarNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics:: TheeconomicsystemDocument8 pagesMicroeconomics:: TheeconomicsystemJorge ArrietaNo ratings yet

- 05Aghion26Bolton ReStud1997Document27 pages05Aghion26Bolton ReStud1997abd. wahid AlfaizinNo ratings yet

- Appecon LessonsDocument38 pagesAppecon LessonsHope Villacarlos NoyaNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics - EssayDocument5 pagesManagerial Economics - EssayJohn JosephNo ratings yet

- An Events Approach To Basic AccountingDocument9 pagesAn Events Approach To Basic AccountingEycha ErozNo ratings yet

- 1.3 The Global Comp IndexDocument30 pages1.3 The Global Comp IndexJohn Mark St BernardNo ratings yet

- Mec 04 2014 15Document8 pagesMec 04 2014 15Hardeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Applied Economic ModuleDocument13 pagesApplied Economic ModuleMark Laurence FernandoNo ratings yet

- N L I U B: Ational AW Nstitute Niversity, HopalDocument14 pagesN L I U B: Ational AW Nstitute Niversity, HopalGoldy SinghNo ratings yet

- Final Economics FD SakshiDocument20 pagesFinal Economics FD SakshiMithlesh ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Unit I - IvDocument97 pagesUnit I - IvSparsh JainNo ratings yet

- 20240326T001347 fbl5030 FBL 5030 Fundamentals of Value Creation in Business Pages 1-9 12-39 40-55 95-126Document85 pages20240326T001347 fbl5030 FBL 5030 Fundamentals of Value Creation in Business Pages 1-9 12-39 40-55 95-126MERVZ TYSONNo ratings yet

- JenniferB - Hinton - Relationship To Profit 2021Document253 pagesJenniferB - Hinton - Relationship To Profit 2021ally gelNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument24 pagesEconomicsraynedhakhadaNo ratings yet

- ECO Part OneDocument18 pagesECO Part Oneragheb hanfiNo ratings yet

- Unit I - IvDocument75 pagesUnit I - IvSparsh JainNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics - Policy AnalysisDocument14 pagesMicroeconomics - Policy AnalysisGaudencio MembrereNo ratings yet

- What Is Economics?: Macroeconomics MicroeconomicsDocument8 pagesWhat Is Economics?: Macroeconomics MicroeconomicsAnonymous tXTxdUpp6No ratings yet

- HRD 2103 NotesDocument60 pagesHRD 2103 NotesOscar WaiharoNo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument17 pagesChapter Onemariam raafatNo ratings yet

- The Econometric SocietyDocument24 pagesThe Econometric Societysara diazNo ratings yet

- 10 2307@3877178 PDFDocument8 pages10 2307@3877178 PDFAlexia NanaNo ratings yet

- Liscow - 2018 - Is Efficiency BiasedDocument70 pagesLiscow - 2018 - Is Efficiency BiasedsamNo ratings yet

- Ohio State University PressDocument16 pagesOhio State University PresstranganNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument54 pagesEconomicskhanxoxo115No ratings yet

- Chethan Kumar K 17BTCOM009Document66 pagesChethan Kumar K 17BTCOM009sandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- PROJECT OF SOUNDARYADocument49 pagesPROJECT OF SOUNDARYAsandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- DocScanner 09-Aug-2023 10-30 amDocument11 pagesDocScanner 09-Aug-2023 10-30 amsandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- project 1.1Document68 pagesproject 1.1sandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- Havells OA Final (1)Document69 pagesHavells OA Final (1)sandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- BEL Project PDFDocument62 pagesBEL Project PDFsandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- Abm Acctg2 Reading Materials 2019Document27 pagesAbm Acctg2 Reading Materials 2019Nardsdel RiveraNo ratings yet

- Identify Overhead Costs 2. Identify Cost Drivers 3. Calculate AR Cost/DriverDocument3 pagesIdentify Overhead Costs 2. Identify Cost Drivers 3. Calculate AR Cost/DriverMitesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Bks 122 - Misingi Ya Sarufi QuestionsDocument4 pagesBks 122 - Misingi Ya Sarufi Questionsnjerustephen806No ratings yet

- Finance ProDocument84 pagesFinance ProdingjcNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis TestsDocument25 pagesFinancial Analysis Teststheodor_munteanuNo ratings yet

- The Business Plan WorksheetDocument13 pagesThe Business Plan WorksheetMadduma, Jeromie G.No ratings yet

- Journal Impact Factor 2015 PDFDocument28 pagesJournal Impact Factor 2015 PDFmalini72No ratings yet

- SAP FICO Zero LevelDocument44 pagesSAP FICO Zero LevelAmit ShindeNo ratings yet

- Aui2601 2017 6 e 2Document8 pagesAui2601 2017 6 e 2Yogesh Batchu100% (1)

- Accounting of DepreciationDocument9 pagesAccounting of DepreciationPrasad BhanageNo ratings yet

- Group 2Document51 pagesGroup 2snehaghagNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 - Audit Acquisition Sample ProblemDocument30 pagesChapter 18 - Audit Acquisition Sample ProblemEldrich BulakNo ratings yet

- Fa1 DocumentationDocument4 pagesFa1 DocumentationJerlin PreethiNo ratings yet

- College Accounting Chapters 1-27-22nd Edition Heintz Test BankDocument25 pagesCollege Accounting Chapters 1-27-22nd Edition Heintz Test BankAmySimonmaos100% (66)

- Report of The Special Examination of Freddie Mac Special Report 122003Document185 pagesReport of The Special Examination of Freddie Mac Special Report 122003lion1king1No ratings yet

- Corporate AccountingDocument93 pagesCorporate AccountingKalp JainNo ratings yet

- Case: Ravi Bose, An NSU Business Graduate With Few Years' Experience As An Equities Analyst, Was Recently Brought in As Assistant To TheDocument13 pagesCase: Ravi Bose, An NSU Business Graduate With Few Years' Experience As An Equities Analyst, Was Recently Brought in As Assistant To TheAtik MahbubNo ratings yet

- 03 Journal EntriesDocument19 pages03 Journal EntriesKumar AbhishekNo ratings yet

- Kieso - Inter - Ch20 - IfRS (Pensions)Document47 pagesKieso - Inter - Ch20 - IfRS (Pensions)Alya SahbrinaNo ratings yet

- BOA Resolution 1 Advertising PDFDocument7 pagesBOA Resolution 1 Advertising PDFNorwel Chavez de RoxasNo ratings yet

- Pat 0075 Cost and Management Accounting Group Assignment Trimester 1, 2015/2016Document8 pagesPat 0075 Cost and Management Accounting Group Assignment Trimester 1, 2015/2016Joel Christian MascariñaNo ratings yet

- Practice Quiz - Chap1Document7 pagesPractice Quiz - Chap1Nada MuchoNo ratings yet

- Chapter I - INTERNAL Auditing: By: Dennis F. GabrielDocument27 pagesChapter I - INTERNAL Auditing: By: Dennis F. GabrielJasmine LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 IFRSDocument28 pagesLecture 5 IFRSyashtilva00000No ratings yet

- PFRS 10 - Consolidate FSDocument11 pagesPFRS 10 - Consolidate FSHannah TaduranNo ratings yet

- State Mining Corporation: Career OpportunitiesDocument38 pagesState Mining Corporation: Career OpportunitiesRashid BumarwaNo ratings yet

- Trial Balance PD Jaya Ban Motor Setelah PenyesuaianDocument1 pageTrial Balance PD Jaya Ban Motor Setelah PenyesuaianHimmalatul Aslami100% (1)

Robinson-AccountingRelationEconomics-1909 (1)

Robinson-AccountingRelationEconomics-1909 (1)

Uploaded by

sandeepattigeri65Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robinson-AccountingRelationEconomics-1909 (1)

Robinson-AccountingRelationEconomics-1909 (1)

Uploaded by

sandeepattigeri65Copyright:

Available Formats

Accounting in Its Relation to Economics

Author(s): Maurice H. Robinson

Source: American Economic Association Quarterly , Apr., 1909, 3rd Series, Vol. 10, No.

1, Papers and Discussions of the Twenty-First Annual Meeting. Atlantic City, N.J.,

December 28-31, 1908 (Apr., 1909), pp. 62-74

Published by: American Economic Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2635412

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Economic

Association Quarterly

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ACCOUNTING IN ITS RELATION TO

ECONOMICS.

MAURICE H. ROBINSON.

"Accounting," according to Lisle,' "is the science which

treats of the methods of recording transactions2 entered

into in connection with the production and exchange of

wealth, and which shows their effect upon its production,

distribution, and exchange." This definition by one of

the foremost Scottish accountants, while obviously in-

complete, possesses the merit of calling attention to the

fundamental economic principles upon which accounting

is based. Whatever the definition adopted, there is uni-

versal agreement that economics is the general science

of wealth. This idea is always present, although the

phraseology differs. Sometimes economics is called "the

science of industrial relations",3 or "the science of busi-

,' 4

ness activities", or "the social science of business".

The two subjects are thus intimately related in that

they each deal with the same subject matter, namely,-

wealth, its production and distribution, together with the

economic relations necessarily involved. Economics,

however, differs from accounting in that it treats of the

nature of wealth and analyzes the conditions under which

it is produced and distributed among the members of so-

ciety. It describes the process of wealth production, the

conditions which facilitate the division of labor and ex-

1 Lisle, Accounting in Theory and Practice, p. i.

2 The word "transactions" includes transfers of materials from

one department of a manufacturing establishment to another, as well

as those where an actual sale is effected.

' Seligman, p. 4.

4 Seager, p. i.

62

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AJccounting in Its Relation to Economics 63

change of products, and the advantages of each; it asks

the question How is the wealth produced by society as

a whole shared by the factors of production and the indi-

viduals who compose each factor? The answers of the

economist to all of these questions are indefinite from the

quantitative standpoint. He finds by historical investi-

gation that wealth may be produced without the aid of

capital; that, however, such a method is slow and ineffi-

cient compared with those where capital joins with labor

and natural resources. The economist as such cannot

tell how much more efficient. For this information he

must turn to his co-worker in economic investigation-

the accountant. The economist analyzes the process

through which wealth, created by the cooperation of pro-

ducing agents, is finally traced to the possession of indi-

viduals who make up the producing society. Here again

he cannot tell how much goes or ought to go to any one

class of claimants, or to any individual of a class. The

accountant mtust be called in, and within certain limits h

is able to measure the conltribution of each factor of pro-

duction and each individual composing each factor. He

also is able to determine the share which each class of

producers and each individual producer gets after the

process of distribution is completed. By comparing these

results he is able to answer the questions which are at the

heart of the social unrest of all ages, namely,-Does the

producer in a complex industrial society receive as a con-

sumer the equivalent of that which he creates as a pro-

ducer? As qualitative chemistry must of necessity pre-

cede and predetermine the conditions under which the

quantitative chemist works, so the economist must first

analyze economic society, differentiate processes, classify

wants, determine the nature of wealth, trace out the intri-

cate economic relationships in both production and dis-

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

64 AA inerican Economnic Associ(W/tioW

tribution, anld, from his analysis of an economic society

and his observation of its workings, formulate economic

laws.

Side by side with the economist, the accountant, work-

ing on the foundations laid by the economist in his anal-

ysis, attempts to determine the economic relationship of

the members of an economic society with definite quan-

titative results. The economist finds that land assists in

production in the form of rent. The accountant deter-

mines how much the land produces and therefore how

much it ought to receive.5 The accountant also finds how

much land actually does receive, and, putting these results

side by side, the economic philosopller may then compare

them and ask the question-Why are they not equivalent?

-and answer it if he can. Applying the same methods,

he determines the creative powers of labor and capital,

and again finds the amount of their share in the actual

distributtion of wealth. In a similar way the economist

may then discuss the relationship of the contribution of

labor and capital respectively, in their joint production,

to their shares in actual distribution. The economist may

discover the reasons why one factor in production does

not receive in any particular case an equivalent of the

share it produces, and, having found the conditions that

have brought abouLt this maladjustment, he may advise

'In actual practice, entrepreneurs bid against each other for the

use of the more desirable locations and for the more fertile plots of

land. Each with the aid of the cost accountant is able to determine

with very great exactness the cost of conducting his business at any

one of several locations. He is also able to estimate approximately

the volume of business which he will be able to carry on and the

prices he will be able to maintain. He therefore knows what he can

pay, and the competition among many entrepreneurs in different

lines of business forces the rent actually paid up to a point approxi-

mately equal to its producing power in the line of business where

the land is most efficient. The accountant finds the limit beyond

which the entrepreneur cannot go and be solvent.

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Accounting in Its Relation to Economi,ics 65

statesmnen and administrators in regard to the kind, na-

ture, and amount of governmental regulation6 that is nec-

essary to properly adjust such conditions and permit a

more equitable distribution of wealth. It will be noticed

that in the practical application of economic principles

the economist is absolutely helpless without the aid of the

accountant, and it is to be observed that the economists

who have contributed the most to the abiding principles of

political economy as accepted today, have in general been

those who have tested their economic principles by the

exact data which the accountant alone can furnish.

Accounting not only applies economic principles to

economic conditions and determines from the quantitative

standpoint existing economic relationships both in the

production and distribution of wealth, but in turn fur-

nishes the facts upon which economic laws are actually

formulated. For example, the economist affirms that

profits tend to be eliminated in the static state; this prin-

ciple might possibly have been evolved in the mind of a

theorist entirely unacquainted with business transactions

and their accounts. It is, however, true that this state-

ment is based upon actual accounting in a large number

of business enterprises as observed by many economists

o Neither the Interstate Commerce Commission, the state commis

sions, nor the courts have any scientific basis for the regulation of

railway rates in accordance with economic principles except so far

as they adopt and apply proper methods of uniform accounting.

The same is also true of public service companies in general, insur-

ance companies, and banks. The work of the Bureau of Municipal

Research has been fruitful in bettering city administi ation because

it has applied scientific accounting methods in connection with the

principles of municipal administration. For an application of the

principles of accounting to a concrete problem in the regulation of

railway rates, see an article by the author of this paper, entitled "The

Legal, Economic and Accounting Principles Involved in the Judicial

Determination of Railway Passenger Rates," in the Yale Review for

February, I908.

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

66 American Economic Association

through an inspection of the data furnished by the ac-

countant. The same statement may also be made in

regard to some of the more recent contributions to the

theory of capital, income, and monopoly profits.

In what has been said the attempt has been made to

draw in rough outline the place that accounting will take

in the future development of economic theory. Today,

for various reasons, accounting falls far short of its pos-

sibilities in this respect. In the first place the economists

have generally had neither the opportunity nor the incli-

nation to master the principles and practice of account-

ing. They have, as a class, therefore, contented them-

selves with making general statements, many of which

have been recast from time to time as the actual facts of

business relations have been disclosed through the more

scientific application of accounting methods; and the pro-

cess is not yet ended. Secondly, accountants are not usu-

ally economists, and therefore their work, lacking the

scientific character which the economist demands for his

purposes, often has little of value to offer when cast in

its present form. An income account, as usually drawn

up, in which the various items are thrown together with-

out reference to their economic character, is well nigh

valueless for the purpose of determining the contribution

of the economic factors to the income produced. The

same is true of the other principal accounts which the

accountant prepares for the information of the business

house for which he is employed; and, finally, the ac-

counts, being drawn up for the purpose of protecting the

proprietor's interests, are naturally enough arranged to

show only his capital, his expenses of production, and his

net earnings. The economist whose chief interest in the

cost of production is from the standpoint of society, often

finds little in the books of a business enterprise to help him

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Accotunting in Its Relation to Economics 67

in his work. An industrial society is, however, made up

of individual business units, and the economist who is

unable to grasp the inter-relations of these business units

and to make the adjustments in the accounts of such busi-

ness units as is necessary in order to make up the balance

sheet and income account of society as a whole, neglects

to take advantage of one of the most valuable methods

for establishing economic principles and economic laws

and eliminating the errors which the economists who

rely wholly on abstract reasoning are liable to commit.

If the principles maintained in this paper are valid, it

naturally follows that:

i. Courses in accounting should be established in

each of the institutions of higher education by the exist-

ing departments of economics, thus maintaining the in-

tegrity of the two branches of the general science of

wealth; and students who are looking forward to careers

as economists, as well as those who expect to enter busi-

ness life, should elect such courses, as a part of their

economic training. Candidates for the doctor's degree in

economics especially ought to be examined in the ele-

ments of accounting, for the reason that such an addition

to the usual course compels accuracy in economic think-

ing, and again since it makes the theory of production

and distribution clearer than is possible by the ordinary

methods of exposition.

2. All accountants, and especially those who are

granted the degree of Certified Public Accountant by

states or by universities, ought to be trained in the princi-

ples of economics. Accounting being the application of

economic principles to definite business transactions, it is,

obvious that if this work is to be raised to a level with the

7 See Fisher, Nature of Capital and Income, chapters on "Capital

Summation" and "Income Summation".

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

68 American Economitc Association

learned professiolns those who enter this field must be

masters of the principles which they are daily applying

in specific cases.

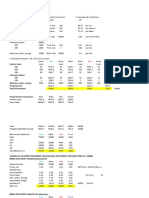

3. The principal sitatements made by accountants.

namely, the balance sheet and the income account, should

be drawn up in accordance with economic principles,-

that is, so that economic units of the same kind should be

collected into the same group. For example, the balance

sheet and income account would then be drawn up in the

following form:

INCOME ACCOUNT

Inventory, Jan. I, I908 $ I,OOO 00 Sales $15,000 00

Purchases for year 10,000 00 Less Freight Outward

Total II,000 00 and Discounts 500 00

Less Inventory,

Jan. I, I909 I,200 00

Cost of goods sold 9,800 00

Freight and Express

Inward 500 00

Total Cost of Goods at

Plant IO,300 00

Earnings of Establish-

ment $ 4,200 00

$ I4,500 00 $I4,500 00

Rent i63 o $ 700 00 Earnings down $4,200 00

Int. on Cap. i9I %0 Soo 00

Wages 591j to 2,500 00

Net profits 421 % 200 00

$4,200 00 $4,200 00

BALANCE SHEET

ASSETS LIABILITIES

i. Investment in Land $Io,ooo 00 I. Obligations to

2. " of Capital Creditors

Buildings $I2,000 00 Mortgage $I5,000 00

Tools & Mach 2,000 00 Accts & Bills

Merchandise I,200 00 Payable 2,000 00

Accts & Bills Total $I7,000 00

Receivable i,500 00 2. Proprietor's Interests

Cash 5,000 00 2I,700 00 Cap. Stock I5,000 00

3. Franchise 5,000 00 Undivided

Profits 4,700 00 I9,700 00

$36,700 00 $36,700 00

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Accounting in Its Relation to Economliics 69

This would enable business men to know what percent-

age of the cost of production was due to rent, interest,

and wages respectively, and when therefore it would be

more economical to increase the interest account by add-

ing inproved machinery rather than the wage account

by adding more laborers. With the usual arrangement

of the income account, this important fact is of course

impossible to ascertain. At the same time, such an ar-

rangement of the income account would enable econo-

mists to make use of the facts of business activities for

the establishment of new economic principles or the cor-

rection of theories formulated without the aid of the

facts which such statements would bring to light. In this

way a gain to both economic theory and sound business

principles would follow.

The evolutionary forces, especially active and persis-

tent in business, are steadily bringing these highly desir-

able ends to a welcome fruition. The process is, how-

ever, a slow one, and I wish therefore to close this paper

with the suggestion that this Round Table, the first

formal gathering of economists and accountants in the

United States for the purpose of engaging in a scientific

discussion of the relationship of the two subjects and

their future development, might render a signal service

to both professions, and to sound business progress at the

same time, by inaugurating a movement looking toward

the fuller application of economic principles in the formal

presentation of the accounts of business establishmnents.8

8The following problem from Lisle's Accoun6ting, page 246, has

been selected in order to further illustrate the principles above

stated. The first solution by the writer of this paper shows,

first, the earnings of the establishment as a whole, and, second, the

distribution of the earnings to land, to capital, to labor, and to the

entrepreneur interests. Owing to the lack of data that would have

been available had the books been kept in accordance with the

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

70 American Economtic Association

Problem: The directors of a malnufacturing company,

before the closing and auditing of the books for the half-

year enlding December 3I, declare out of the net earn-

ings of the company a dividend for the half-year of 4 per

cent on the preferred stock of $40,000, and of 3 per cent

on the ordinary stock of $40,ooo. There has been brought

forward from the last half-year an undivided balance of

profit of $i6oo, and after the audit of the books the trial

balance is founld to be as follows:

TRIAL BALANCE AS AT 3IST DECEMBER

Preferred Stock $40,000 00

Ordinary Stock 40,000 00

Sales 87,670 00

Bills Payable IO,400 00

Accounts Payable 4,000 00

Profit and Loss Account I,6oo 00

Property and Buildings $I3,000 00

Plant and Machinery i6,ooo 00

Patents and Goodwill 32,000 00

Stock on hand, Ist July II,6oo 00

Purchases 33,000 00

Wages 35,200 00

Coal 2,400 00

Salaries, general 4,400 00

" management 2,000 00

Insurance 350 00

Repairs 400 00

Discount and Allowances 2,500 00

Freight 6oo 00

Discount and Interest 300 00

Cash in Bank 3,200 00

Investments 6,200 00

Miscellaneous Expenses I,720 00

Book Debts iS,8oo 00

$183,670 00 $I83,670 00

methods proposed; it has been assumed that the term "property and

buildings" includes land and any investment upon it which may

properly be included under that title; that "plant and machinery"

are capital in the limited sense in which that term is used; that

"miscellaneous expenses" are in reality wages and therefore properly

included under that head. In the problem and its solution the

dollar mark has been substituted for the English pound. Since the

company owned the land and furnished part of the capital invested

upon it, an arbitrary rate of return has been assumed upon these

investments.

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Accounting in Its Relation to Econoiinics 7I

The stock on hand December 3I is $io,6oo. Pre-

pare profit and loss account and balance sheet from the

above, giving effect in the accounts to depreciation at the

rate of six per cent per annum on plant and nmachinery,

and an allowance of five per cent on book debts to provide

for bad accounts; also create a liability in the balance

sheet for the dividends declared as above stated.

The second solution by Lisle, while not drawn up in accordance

with the best practice, is a fair example of the usual method of

grouping the various items in the ordinary income account and

balance sheet.

It will be noticed that the solution by the writer gives all of the

information furnished by the usual method and in addition shows,

first, what the establishment earns, and, second, the share of the

earnings which go to the several factors of production. This would

enable the statistician in the course of a few years to prepare

exceedintgly valuable tables for the guidance of the business manager

in directing the affairs of the company.

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

72 Avierican Economic Association

o0 00 0 O O

0OO O0 0 0 ? 01

H 00t 00 c f

4 4 CIS 0.) 4 4

o 0 oo 0 0

'j ? in -, o 8 0 0

co O 6u

H H HH

88 88 8

m 8 e 8a1 8 8~~~0

? 1 aS" ' ' S. ,5?, h h 0

r en- ? 0 XX

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Accounting in Its Relation to Economtics 73

0 0 00 0

0 0 00 0

0 0 0 00

0 0 0 i0 I0

0 0 i0 cn C

~~~16 -~~~~~~ C~ C;)

It

C,) UC

4.4 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~0

b1.0

_q

0 (U

E 0

0~~~~~~~~00

E-4 0 ~ 0 oo

00

81 00 0 000

o ) &~~~~~~~~~ ~ 00 00 0 0c,0c

*~0 0 ~

U) )C)~~~~ 0~~~8CC0 8 0 8 00

n 0) n 0 iO

0n0 O 0jin

t00 0'

0' H CC) in 0 C

0 0 0 0 0

0o 0 0 0 o 8

W110 0 0 t 0

0-4 -0 0 tn 0 0

w C4CC-

C0 g i0 4 c )

8 8888 CC

8 80

88

0~ 0

c t8 > 8 88

4.4 00 -) 0

~~10 ~ 0 CC).) 0CC

N cn f 8 o 0

a- 0 z gW 0 baX fa e 0 0 0 , 0

It HTt U

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

74 American Economic Association

SECOND SOLUTION

PROFIT AND Loss ACCOUNT FOR HALF-YEAR

To Cost of Goods By Sales $87,670 00

Stock on hand, July i $ii,6oo 00

Purchases 33,000 00

$44,600 oo

Deduct stock on

hand, December 3I io,6oo 00

$34,000 00

To Wages 35,200 00

To Coal 2,400 00

To Salaries, general 4,400 00

To " management 2,000 00

To Insurance 350 00

To Repairs 400 00

To Discount and al-

lowances 2,500 00

To Freight 600 oo

To Discount and

interest 300 00

To Miscellaneous ex-

penses I, 720 00

To Allowance for bad

debts 940 00

To Depreciation 480 00

$85,290 00

To Profit for year 2,380 00

$87,670 00 $87,670 00

To Dividend for half- By Balance i,6oo 00

year on preference By Profit for half-

shares $ 800 oo year as above 2,380 00

To do. on ordinary

shares 6oo 00

To Balance 2,580 00

$3,80 00 $3.980 00

BALANCE SHEET

LIABILITIES ASSETS

Accounts payable $ 4,000 00 Book debts $I8,800 00

Bills payable IO,400 00 Less allowance

Due to shareholders: for bad debts 940 00

Preference II 7, 860 00

stock $40,000 00 Stock on hand .io,6oo 00

Ordinary Investments 6,200 00

stock 40,000 00 Plant and

Dividend for machinery $I6,ooo 00

half-year on Less 3 % 480 00 15 520 00

preferred 00 Property and

Dividend for buildings I3,000 00

half-ear fo Patents and good

half-year on wl 2000

ordinary stock 6oo 00 will 32,200 00

Undivided Cash in bank 3,200 00

profit 2,580 00 83,980 00

$98,380 00 $98,380 00

This content downloaded from

110.225.45.183 on Thu, 11 Apr 2024 16:06:30 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Accounting Entry-Level TestDocument13 pagesAccounting Entry-Level TestQazi HammadNo ratings yet

- Economic Analysis For Business, Managerial Economics, MBA EconomicsDocument215 pagesEconomic Analysis For Business, Managerial Economics, MBA EconomicsSaravananSrvn90% (10)

- Blaine Kitchenware, Inc. - Capital Structure DATADocument5 pagesBlaine Kitchenware, Inc. - Capital Structure DATAShashank Gupta100% (1)

- Running Head: Financial Statement Analysis of Samsung 1Document19 pagesRunning Head: Financial Statement Analysis of Samsung 1Sangita GautamNo ratings yet

- Robinson AccountingRelationEconomics 1909Document14 pagesRobinson AccountingRelationEconomics 1909Dhruv SharmaNo ratings yet

- Suntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines London School of EconomicsDocument21 pagesSuntory and Toyota International Centres For Economics and Related Disciplines London School of EconomicsFelicia AprilianiNo ratings yet

- CoasefirmaDocument21 pagesCoasefirmaFernanda SennaNo ratings yet

- Accounting For LawyersDocument150 pagesAccounting For LawyersvivienkiigeNo ratings yet

- The Nature of FirmDocument21 pagesThe Nature of FirmMuhammad UsmanNo ratings yet

- Llewellyn, K. N. 1925. The Effect of Legal Institutions Upon Economics. The American Economic Review-2Document20 pagesLlewellyn, K. N. 1925. The Effect of Legal Institutions Upon Economics. The American Economic Review-2phngnguyn2706No ratings yet

- Contemporary Accting Res - 2021 - Hanlon - Behavioral Economics of Accounting A Review of Archival Research On IndividualDocument65 pagesContemporary Accting Res - 2021 - Hanlon - Behavioral Economics of Accounting A Review of Archival Research On IndividualNur Hidayah K FNo ratings yet

- Abegail Blanco Mm2-IDocument9 pagesAbegail Blanco Mm2-IAbegail BlancoNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Accountability From The For Itself To The For The Other 2002 Accounting, Organizations and SocietyDocument33 pagesEthics and Accountability From The For Itself To The For The Other 2002 Accounting, Organizations and SocietyiportobelloNo ratings yet

- Me Chapter OneDocument6 pagesMe Chapter OneSherefedin AdemNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument145 pagesEconomicsSaeed WataniNo ratings yet

- A Note On Welfare Propositions in EconomicsDocument13 pagesA Note On Welfare Propositions in EconomicsmkatsotisNo ratings yet

- Income 1925Document9 pagesIncome 1925Ayush SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Introduction To Economic TheoryDocument12 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction To Economic TheoryMaria Teresa Frando CahandingNo ratings yet

- Coase The Nature of The FirmDocument21 pagesCoase The Nature of The FirmMarcosNo ratings yet

- Ronald Coase - The Nature of The FirmDocument21 pagesRonald Coase - The Nature of The FirmIan BotelhoNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of Macro Economic Issues: Unit IDocument38 pagesNature and Scope of Macro Economic Issues: Unit IVig NeshNo ratings yet

- 1977, The Municipal Accounting Maze, An Analysis of Political Incentives, ZimmermanDocument39 pages1977, The Municipal Accounting Maze, An Analysis of Political Incentives, ZimmermanIrham PNo ratings yet

- Eco 3rd Sem Chapter 2Document10 pagesEco 3rd Sem Chapter 2Athul MNo ratings yet

- List of Basic Economic Problems and Their SolutionDocument3 pagesList of Basic Economic Problems and Their SolutionSheryl BorromeoNo ratings yet

- A M U, A: Ligarh Uslim Niversity LigarhDocument13 pagesA M U, A: Ligarh Uslim Niversity LigarhKajal SinghNo ratings yet

- Ecm Pro 071265Document61 pagesEcm Pro 071265Olivia FelNo ratings yet

- Basic Economics With LRTDocument4 pagesBasic Economics With LRTtrix catorceNo ratings yet

- Modern Economy - SS11Document18 pagesModern Economy - SS11Christine Joy MarcelNo ratings yet

- Economics I ProjectDocument14 pagesEconomics I ProjectGoldy SinghNo ratings yet

- Ecn 211 Lecture Note Moodle 1Document13 pagesEcn 211 Lecture Note Moodle 1AdaezeNo ratings yet

- Introduction and Definitions (Lesson 1) Basic MicroDocument10 pagesIntroduction and Definitions (Lesson 1) Basic MicroMark Laurenze MangaNo ratings yet

- Couse Name: Managerial Economics Course Code: MGMT4062 Unit 1: Basics of Managerial EconomicsDocument11 pagesCouse Name: Managerial Economics Course Code: MGMT4062 Unit 1: Basics of Managerial Economicskunal kashyapNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Principles of MicroeconomicsDocument3 pagesAssignment 3 Principles of MicroeconomicsChris MwaiNo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDocument4 pagesBachelor of Secondary Education - Social Studies - Set C: Activity in MicroeconimicsDave EscalaNo ratings yet

- Equity Theories Past Present and Future Carien Van Mourik 2010Document19 pagesEquity Theories Past Present and Future Carien Van Mourik 2010Firmansyah DjafarNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics:: TheeconomicsystemDocument8 pagesMicroeconomics:: TheeconomicsystemJorge ArrietaNo ratings yet

- 05Aghion26Bolton ReStud1997Document27 pages05Aghion26Bolton ReStud1997abd. wahid AlfaizinNo ratings yet

- Appecon LessonsDocument38 pagesAppecon LessonsHope Villacarlos NoyaNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics - EssayDocument5 pagesManagerial Economics - EssayJohn JosephNo ratings yet

- An Events Approach To Basic AccountingDocument9 pagesAn Events Approach To Basic AccountingEycha ErozNo ratings yet

- 1.3 The Global Comp IndexDocument30 pages1.3 The Global Comp IndexJohn Mark St BernardNo ratings yet

- Mec 04 2014 15Document8 pagesMec 04 2014 15Hardeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Applied Economic ModuleDocument13 pagesApplied Economic ModuleMark Laurence FernandoNo ratings yet

- N L I U B: Ational AW Nstitute Niversity, HopalDocument14 pagesN L I U B: Ational AW Nstitute Niversity, HopalGoldy SinghNo ratings yet

- Final Economics FD SakshiDocument20 pagesFinal Economics FD SakshiMithlesh ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- Unit I - IvDocument97 pagesUnit I - IvSparsh JainNo ratings yet

- 20240326T001347 fbl5030 FBL 5030 Fundamentals of Value Creation in Business Pages 1-9 12-39 40-55 95-126Document85 pages20240326T001347 fbl5030 FBL 5030 Fundamentals of Value Creation in Business Pages 1-9 12-39 40-55 95-126MERVZ TYSONNo ratings yet

- JenniferB - Hinton - Relationship To Profit 2021Document253 pagesJenniferB - Hinton - Relationship To Profit 2021ally gelNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument24 pagesEconomicsraynedhakhadaNo ratings yet

- ECO Part OneDocument18 pagesECO Part Oneragheb hanfiNo ratings yet

- Unit I - IvDocument75 pagesUnit I - IvSparsh JainNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics - Policy AnalysisDocument14 pagesMicroeconomics - Policy AnalysisGaudencio MembrereNo ratings yet

- What Is Economics?: Macroeconomics MicroeconomicsDocument8 pagesWhat Is Economics?: Macroeconomics MicroeconomicsAnonymous tXTxdUpp6No ratings yet

- HRD 2103 NotesDocument60 pagesHRD 2103 NotesOscar WaiharoNo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument17 pagesChapter Onemariam raafatNo ratings yet

- The Econometric SocietyDocument24 pagesThe Econometric Societysara diazNo ratings yet

- 10 2307@3877178 PDFDocument8 pages10 2307@3877178 PDFAlexia NanaNo ratings yet

- Liscow - 2018 - Is Efficiency BiasedDocument70 pagesLiscow - 2018 - Is Efficiency BiasedsamNo ratings yet

- Ohio State University PressDocument16 pagesOhio State University PresstranganNo ratings yet

- EconomicsDocument54 pagesEconomicskhanxoxo115No ratings yet

- Chethan Kumar K 17BTCOM009Document66 pagesChethan Kumar K 17BTCOM009sandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- PROJECT OF SOUNDARYADocument49 pagesPROJECT OF SOUNDARYAsandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- DocScanner 09-Aug-2023 10-30 amDocument11 pagesDocScanner 09-Aug-2023 10-30 amsandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- project 1.1Document68 pagesproject 1.1sandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- Havells OA Final (1)Document69 pagesHavells OA Final (1)sandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- BEL Project PDFDocument62 pagesBEL Project PDFsandeepattigeri65No ratings yet

- Abm Acctg2 Reading Materials 2019Document27 pagesAbm Acctg2 Reading Materials 2019Nardsdel RiveraNo ratings yet

- Identify Overhead Costs 2. Identify Cost Drivers 3. Calculate AR Cost/DriverDocument3 pagesIdentify Overhead Costs 2. Identify Cost Drivers 3. Calculate AR Cost/DriverMitesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Bks 122 - Misingi Ya Sarufi QuestionsDocument4 pagesBks 122 - Misingi Ya Sarufi Questionsnjerustephen806No ratings yet

- Finance ProDocument84 pagesFinance ProdingjcNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis TestsDocument25 pagesFinancial Analysis Teststheodor_munteanuNo ratings yet

- The Business Plan WorksheetDocument13 pagesThe Business Plan WorksheetMadduma, Jeromie G.No ratings yet

- Journal Impact Factor 2015 PDFDocument28 pagesJournal Impact Factor 2015 PDFmalini72No ratings yet

- SAP FICO Zero LevelDocument44 pagesSAP FICO Zero LevelAmit ShindeNo ratings yet

- Aui2601 2017 6 e 2Document8 pagesAui2601 2017 6 e 2Yogesh Batchu100% (1)

- Accounting of DepreciationDocument9 pagesAccounting of DepreciationPrasad BhanageNo ratings yet

- Group 2Document51 pagesGroup 2snehaghagNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 - Audit Acquisition Sample ProblemDocument30 pagesChapter 18 - Audit Acquisition Sample ProblemEldrich BulakNo ratings yet

- Fa1 DocumentationDocument4 pagesFa1 DocumentationJerlin PreethiNo ratings yet

- College Accounting Chapters 1-27-22nd Edition Heintz Test BankDocument25 pagesCollege Accounting Chapters 1-27-22nd Edition Heintz Test BankAmySimonmaos100% (66)

- Report of The Special Examination of Freddie Mac Special Report 122003Document185 pagesReport of The Special Examination of Freddie Mac Special Report 122003lion1king1No ratings yet

- Corporate AccountingDocument93 pagesCorporate AccountingKalp JainNo ratings yet

- Case: Ravi Bose, An NSU Business Graduate With Few Years' Experience As An Equities Analyst, Was Recently Brought in As Assistant To TheDocument13 pagesCase: Ravi Bose, An NSU Business Graduate With Few Years' Experience As An Equities Analyst, Was Recently Brought in As Assistant To TheAtik MahbubNo ratings yet

- 03 Journal EntriesDocument19 pages03 Journal EntriesKumar AbhishekNo ratings yet

- Kieso - Inter - Ch20 - IfRS (Pensions)Document47 pagesKieso - Inter - Ch20 - IfRS (Pensions)Alya SahbrinaNo ratings yet

- BOA Resolution 1 Advertising PDFDocument7 pagesBOA Resolution 1 Advertising PDFNorwel Chavez de RoxasNo ratings yet

- Pat 0075 Cost and Management Accounting Group Assignment Trimester 1, 2015/2016Document8 pagesPat 0075 Cost and Management Accounting Group Assignment Trimester 1, 2015/2016Joel Christian MascariñaNo ratings yet

- Practice Quiz - Chap1Document7 pagesPractice Quiz - Chap1Nada MuchoNo ratings yet

- Chapter I - INTERNAL Auditing: By: Dennis F. GabrielDocument27 pagesChapter I - INTERNAL Auditing: By: Dennis F. GabrielJasmine LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5 IFRSDocument28 pagesLecture 5 IFRSyashtilva00000No ratings yet

- PFRS 10 - Consolidate FSDocument11 pagesPFRS 10 - Consolidate FSHannah TaduranNo ratings yet

- State Mining Corporation: Career OpportunitiesDocument38 pagesState Mining Corporation: Career OpportunitiesRashid BumarwaNo ratings yet

- Trial Balance PD Jaya Ban Motor Setelah PenyesuaianDocument1 pageTrial Balance PD Jaya Ban Motor Setelah PenyesuaianHimmalatul Aslami100% (1)