Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The History of Hollywood's Studio System-Starring: Technology

The History of Hollywood's Studio System-Starring: Technology

Uploaded by

Raechel WongOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The History of Hollywood's Studio System-Starring: Technology

The History of Hollywood's Studio System-Starring: Technology

Uploaded by

Raechel WongCopyright:

Available Formats

Wong 1 Raechel Wong COSF 186 Professor Govil January 23rd, 2011 The History of Hollywood's Studio SystemStarring:

Technology Scholar Tom Schatz writes that from the 20's to the 40's the Hollywood studio system referred both to a factory-based mode of film production and also, crucially, to the vertical integration of production, distribution and exhibition (Schatz 15). The Hollywood studio system was comprised of The Big Five and three minor studios (or the Big Eight) and functioned as an oligopoly; these studios controlled massive proportions of the global film industry revenue, each producing and controlling the fate of their own films, players and theatres by contracts (Schatz 15). With so many changes and factors, is there an aspect of the Hollywood studio system that can be traced from its beginning to its end? While the history of the studio system is intricate and involves many moving pieces, one can follow the timeline with various technologies that provoked the system to grow, to an extent that technology has played a part in the rise, growth and fall of the studio system. The studio system began it's development in the 1910's and saw its decline in 1948 during this period, the technologies that came about perpetuated the forward motion of the studio system as well as its dismissal (Gomery 247). Several factors led to the studio systems rise; Gomery writes that the invention of sound technology in films brought film making into the studio and delivered the world market of cinema to Hollywood's doorstep (Gomery 247). Sklar's wealth of knowledge on the advent of talkies within historical context sheds much insight on Hollywood's domination of the global movie market. Sklar pays homage to the truth of the plot behind Singin' in the Rain but ultimately says that the crucial changes caused by the spoken word had to do not with the players but with the technology of moviemaking (Sklar 154). The simplicity of the silent era was over and the reign of the talkie brought about a hefty obstacle of revolutionising the industry. Massive changes in the production

Wong 2 and exhibition scenes were required; studios overhauled their sets by building soundproof stages and rigged their theatres with sound equipment (Sklar 154). Sound was united with picture at the same time that Soviet silents (such as Eisenstein's Potemkin) began to trump American ones with their aesthetic and political standards (Sklar 156). The advent of sound technology returned the attention of film-lovers to the US by recapturing the centre stage by a technological counterrevolution that reformulated the elements of cinema expression and gave new vitality and validity to the familiar mode of capitalist commercial cinema (Sklar 156). Of course, with the new technology, came new challenges from the government; how to censor films became a difficult task because sound was recorded on a disc that could not be edited (Sklar 154). As a result, a new Production Code was launched in the 30's and internal selfcensorship imposed by Will Hays was made known (Sklar 154). Lastly, but certainly not least, sound technology helped to further solidify another main aspect of the studio system's rise: vertical integration. Sklar writes that sound forced movie moguls into a new realm of industrial and financial enterprise; because sound was not yet part of the film industry, there was room for further mergers (Sklar 156). Radio Corporation of America, who created a sound system for the film industry took over a studio and an exhibition company to create RKO (Sklar 156). The ability of studios to own exhibition ventures solidified their control over the movie marketplace (Gomery 247). Schatz writes that the vertical integration (the combination of production, distribution and exhibition, all controlled by one studio) that took place in the 20's allowed the studio system to form into a mature oligopoly by the 30's (Schatz 15). During the Great Depression and the second World War, the studio system sailed on in its monopolistic form, utilising it's contract system that kept a hand-picked labour force within the family of the studio (Schatz 15). Vertical integration and subcontracting kept funds, profits and talent within the studio. Vertical integration often happened as a result of mergers between companies that were already experienced in their specialities, which is how the 3-step dance of production, distribution and exhibition functioned so well.

Wong 3 How the studio system functioned was also dependent on technology on an international scale; because film was made in a universal format, Hollywood films could cross the globe with few problems. The other basic elements of Hollywood's studio system consisted of a bi-coastal industry, vertical integration, a rationalisation of system and the volatility between the various divisions of labour. Finance and management took place in New York while filming and production took place in Los Angeles (Schatz 15). Within the studio, production, distribution and exhibition was all executed. One of the facets of vertical integration was block-booking, which helped the Big Eight studios (which included MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, Paramount, RKO, Universal, Columbia and United Artists) take over the national and global market; in response,foreign countries tried to set up production quotas to boost their own film industry (Sklar 215). These quotas were obstacles to American studios, but they were able to work around the system by sending their own producers to foreign studios to shoot quota quickies (Sklar 220). The rationalisation of the studio system involved the management and creation of line-byline budgets, the division of labour and breakdown schedules that included scripts to work off of. The system's rationalisation allowed for stricter finance control, efficiency, and it allowed management to scrutinise every point of spending and production. In terms of the tension between the various divisions of labour, stars began to negotiate their salaries with studios after it was realised that stars were a hefty benefactor for sales. Before the studio system fully emerged, reformers reared their heads at any point in cinema that felt uncouth or needed censorship, making it essential for stars to maintain a moral lifestyle to project the social health of the cinema (Peiss 162). As a result of this need for stars to play off regulations, audiences began to fall in love with particular players, creating fan bases and demand for these stars (de Cordova 102). The demand reshaped the star as a commodity and studios had to adjust for the creation of this new market by utilising their players as a chief means of product differentiation (de Cordova 112). Despite the continual additions to the studio system's buoyancy, several changes were to come, both technology-oriented and non-technology-oriented, that would that would collapse the entertainment

Wong 4 empire that was built in in the first half of the 20th century. Gomery sums up the fall of the Hollywood studio system into three main points: the rise of television, the Paramount antitrust decrees and suburbanisation of the US and the baby boom (Gomery 247). The innovation and spread of television was triggered by the baby-boom and suburbanisation of the US, which was in turn propelled by sustained economic prosperity and wholesale changes in postwar American lifestyles (Schatz 16). TelevisionAmerica's [new] dominant form of habituated, mass-media narrative entertainmentpulled entertainment into the private sphere and cinema began to suffer (Schatz 16). Technological innovation was a direct response to threats of television technology: new innovations like smell-o-vision, 3D, and cinevision were responses to the rise of television, to draw audiences back to the cinema. Though this was an obstacle for studios, not all studios saw it as such; smaller, independent studios took advantage of television as a new exhibition platform. The larger studios saw the profit made from television and pushed their back catalogue films to television. Another major strike that added to the collapse of the studio system was the Paramount antitrust decree. Independent film companies and the government had kept their lawsuits and eyes on Hollywood's studio system and saw its tremendous power as a national industry and a global player. The Supreme Court decided it was time to put a stop to the studio system's reign. The Paramount decree prevented studios from being able to hold their own exhibition interests and the new industrial regulations forced studios to sell their picture palaces (Gomery 247). The decree also prohibited the collusive trade practices that were crucial to the studios' control of the motion-picture marketplace (Schatz 16). By the 70's, Hollywood backtracked to its old form when production, distribution and exhibition were separate affairs (Sklar 290). In the 70's, the Hollywood corporations turned into media conglomerates, which were involved in more forms of media than just film; they incorporated music, magazines, books, newspapers and the like into their repertoire (Gomery 250). Disneyland, for example, includes all of the above and even has utilised a theme park as part of its conglomeration. Hollywood

Wong 5 blockbusters like Jaws opened up a new opportunity for studios; these films were quickly paced with high budgets and massive nationwide releases (Gomery 249). Thanks to the advent of television, the blockbuster was heavily advertised and raked in audiences and huge profits. The culture of film also remained reliant on stars at the helm as tent-pole productions hit the theatres. Today's system of conglomerate-Hollywood mirrors the studio system closely in that the majority of the revenue from film goes to a few large conglomerates (Schatz 25). Through the history of the studio system, technology always had a role, whether it was the star, the supporting actor or even the player with a just cameo. Though the studio system may be long gone, the oligopoly seems very much alive: the six media conglomerates which dominate contemporary Hollywood now possess a power and cohesion against which the oligopoly of the Hollywood studios during the 1930's and 1940's simply pales in comparison (Gomery 252). Gomery writes that today, Hollywood as an industry has also continued to redefine itself, principally by adding to its technological bag of tricks (Gomery 249). It is arguable that it is the new technological platforms by which we watch films that define the era of contemporary cinema, just as technologies in the past defined the history of the Hollywood studio system (Gomery 250).

Works Cited 1DeCordova, Richard. Picture Personalities: the Emergence of the Star System in America. Urbana: University of Illinois, 1990. Print.

Wong 6 2Gomery, Douglas. "Hollywood as Industry." American Cinema and Hollywood: Critical Approaches. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. 245-54. Print. 3Peiss, Kathy Lee. "Cheap Theatre and the Nickel Dumps." Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1986. 13962. Print. 4Schatz, Tom. "The Studio System and Conglomerate Hollywood." The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2008. 13-42. Print. 5Sklar, Robert. Movie-made America: a Social History of American Movies. New York: Random House, 1975. Print.

You might also like

- Salaar Part 1 - CeasefireDocument24 pagesSalaar Part 1 - Ceasefiresaikik9940% (1)

- Attagari Kathalu by Bhanumati RamakrishnaDocument150 pagesAttagari Kathalu by Bhanumati RamakrishnaPrasanth Kumar93% (14)

- Edith Head - The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood's Greatest Costume DesignerDocument606 pagesEdith Head - The Fifty-Year Career of Hollywood's Greatest Costume DesignerShaban Kamuiru100% (5)

- Miriam Ross Film Festival As ProducerDocument7 pagesMiriam Ross Film Festival As ProducerAlejandro Pérez EyzellNo ratings yet

- The Contemporary Hollywood Film IndustryDocument2 pagesThe Contemporary Hollywood Film IndustryMaria ContrerasNo ratings yet

- The Hollywood Mode of ProductionDocument233 pagesThe Hollywood Mode of ProductionAndres AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Lons Le Saunier Mediatheque RO BUNDocument2 pagesLons Le Saunier Mediatheque RO BUNDiana Andreea BadraganNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of The Hollywoodstudio SystemDocument1 pageThe Emergence of The Hollywoodstudio SystemDarshan PatilNo ratings yet

- The SAGE Handbook of Media StudiesDocument22 pagesThe SAGE Handbook of Media StudiesFisgon Gonzaga Pelusuelta0% (1)

- CinemaDocument24 pagesCinemaViplav KumarNo ratings yet

- List of Headings - The Hollywood Film IndustryDocument2 pagesList of Headings - The Hollywood Film IndustryNgo Phuong MaiNo ratings yet

- Yoon Malecki 2009Document33 pagesYoon Malecki 2009Ioana-Claudia MateiNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two: Distribution in Practice The Hollywood ModelDocument58 pagesChapter Two: Distribution in Practice The Hollywood ModelLa Bomba VergaraNo ratings yet

- Playing the Percentages: How Film Distribution Made the Hollywood Studio SystemFrom EverandPlaying the Percentages: How Film Distribution Made the Hollywood Studio SystemNo ratings yet

- Hollywood Dominance of The Movie IndustryDocument4 pagesHollywood Dominance of The Movie IndustryDwiki Aprinaldi100% (1)

- US MOVIE DistributionDocument30 pagesUS MOVIE DistributionMARCUS SNOWWENo ratings yet

- Sony&Loews Case StudyDocument9 pagesSony&Loews Case StudyElian Alexander Cruz DominguezNo ratings yet

- Scott PaperDocument20 pagesScott PaperGeorgiana MazareanuNo ratings yet

- The Movie Industry: Fundemantals of Cinema (Prof. Zeynep Çetin Erus) Chapter Recap and Study GuideDocument6 pagesThe Movie Industry: Fundemantals of Cinema (Prof. Zeynep Çetin Erus) Chapter Recap and Study GuideJokas 00No ratings yet

- Cartoon Planet: Worlds of Production and Global Production Networks in The Animation IndustryDocument34 pagesCartoon Planet: Worlds of Production and Global Production Networks in The Animation IndustryandrooNo ratings yet

- Deakin Research Online: This Is The Published VersionDocument13 pagesDeakin Research Online: This Is The Published VersionAlex WarolaNo ratings yet

- Film Production Theory - Film Production Theory-SUNY Press (2000)Document618 pagesFilm Production Theory - Film Production Theory-SUNY Press (2000)Carlos_DowlingNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Independent FilmDocument17 pagesThe Impact of Independent FilmnoahsheirNo ratings yet

- Amc 5172514Document33 pagesAmc 5172514martinbouchet9475No ratings yet

- Explanation in Arts AppreciationDocument2 pagesExplanation in Arts AppreciationAbdulwarith AWALNo ratings yet

- Publisher Version (Open Access)Document15 pagesPublisher Version (Open Access)Riyan RismayanaNo ratings yet

- Globalisation of The Film IndustryDocument16 pagesGlobalisation of The Film Industryyog devi100% (1)

- Studio FilmDocument5 pagesStudio FilmlahyouhNo ratings yet

- Film IndustryDocument48 pagesFilm IndustryDas BiswajitNo ratings yet

- What Topic Is Your Research On?: The American Film Industry - A Model of OligopolyDocument2 pagesWhat Topic Is Your Research On?: The American Film Industry - A Model of OligopolySushil DevNo ratings yet

- Cinema HistoryDocument29 pagesCinema HistoryJosephine EnecuelaNo ratings yet

- The Film IndustryDocument4 pagesThe Film Industrydaisy jeropNo ratings yet

- Digital Dawn A Revolution in Movie DistributionDocument32 pagesDigital Dawn A Revolution in Movie DistributionRomdhi Fatkhur RoziNo ratings yet

- VHSDocument15 pagesVHSMiekMariek100% (1)

- Tewnty First Century FoxDocument16 pagesTewnty First Century FoxAnkur ShrimaliNo ratings yet

- CinemaDocument4 pagesCinemaAnamozartNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Exhibition Methods of CinemaDocument2 pagesEvolution of Exhibition Methods of Cinemaryb2v9b6nrNo ratings yet

- Barthelomew Gerald Aguugo AssignmentDocument7 pagesBarthelomew Gerald Aguugo AssignmentBarth GeraldNo ratings yet

- Angel Lucario - Ap Lang Choice Research PaperDocument10 pagesAngel Lucario - Ap Lang Choice Research Paperapi-550918061No ratings yet

- 8 Lorenzen Globalization Film Industry 08Document16 pages8 Lorenzen Globalization Film Industry 08Thkrn PrshtNo ratings yet

- 05 The End of The Studio SystemDocument6 pages05 The End of The Studio SystemMissSRyanNo ratings yet

- Hollywood CinemaDocument28 pagesHollywood CinemaPasty100% (1)

- How Does Jurassic Park Epitomize The Hollywood BlockbusterDocument6 pagesHow Does Jurassic Park Epitomize The Hollywood BlockbusterSam CalvertNo ratings yet

- Andrew An Atlas of World Cinema PDFDocument16 pagesAndrew An Atlas of World Cinema PDFdaniel kiwiNo ratings yet

- Dudley Andrew An Atlas of World CinemaDocument16 pagesDudley Andrew An Atlas of World Cinemaozen.ilkimmNo ratings yet

- Blueprint For A New HollywoodDocument30 pagesBlueprint For A New Hollywoodelerom32No ratings yet

- FilmsDocument3 pagesFilmsthisisspam10000No ratings yet

- The Journal of Popular Culture " - Securing The Success of Transformers - Age of ExtinctionDocument24 pagesThe Journal of Popular Culture " - Securing The Success of Transformers - Age of ExtinctionPanca WahyudiNo ratings yet

- Makale The Rise of Domestic Pop Erus 2020 0267323120928216Document15 pagesMakale The Rise of Domestic Pop Erus 2020 0267323120928216SENANo ratings yet

- Movie Theaters Are On Life Support - How Will The Film Industry Adapt?Document4 pagesMovie Theaters Are On Life Support - How Will The Film Industry Adapt?Lakshmi .R.PillaiNo ratings yet

- The Film Studies TIme LineDocument3 pagesThe Film Studies TIme LineMarcus WrightNo ratings yet

- .2 Hollywood's Economic LeadershipDocument3 pages.2 Hollywood's Economic LeadershipAnand Kumar BhagatNo ratings yet

- Art - The History of CinemaDocument29 pagesArt - The History of CinemaAlloySebastinNo ratings yet

- Ma. Michelle L. Whiting Columbian Southern University MBA 6641-20I-1A22-S1, International Economics Dr. Keith A. Wade August 24 2021Document6 pagesMa. Michelle L. Whiting Columbian Southern University MBA 6641-20I-1A22-S1, International Economics Dr. Keith A. Wade August 24 2021MWhite100% (1)

- History of CinemaDocument2 pagesHistory of CinemaAcostaNo ratings yet

- Caston 2012Document16 pagesCaston 2012Al ShaheemNo ratings yet

- An Age of Anxiety: Ixs&feature RelatedDocument32 pagesAn Age of Anxiety: Ixs&feature RelatedJosh VuNo ratings yet

- The '90s: The Golden Age of Cinema - Defining Movies of the DecadeFrom EverandThe '90s: The Golden Age of Cinema - Defining Movies of the DecadeNo ratings yet

- A History of American Movies: A Film-by-Film Look at the Art, Craft, and Business of CinemaFrom EverandA History of American Movies: A Film-by-Film Look at the Art, Craft, and Business of CinemaNo ratings yet

- Settle 5Document6 pagesSettle 5deafrh4No ratings yet

- The End of Cinema As We Know It and I FeelDocument5 pagesThe End of Cinema As We Know It and I FeelbeydaNo ratings yet

- Film As International Business: ThomasDocument12 pagesFilm As International Business: Thomashrishikesh arvikarNo ratings yet

- History of Cinema: Hollywood and The Production CodeDocument78 pagesHistory of Cinema: Hollywood and The Production CodeLucasGómezNo ratings yet

- Information DirectorateDocument5 pagesInformation DirectorateresearcherkajalNo ratings yet

- Superintendent Seniority ListDocument547 pagesSuperintendent Seniority ListGopalrao KaranamNo ratings yet

- Nadeem Shravan - Management Lessons UploadDocument15 pagesNadeem Shravan - Management Lessons UploadTanveer KhanNo ratings yet

- Lyotard - AcinemaDocument13 pagesLyotard - AcinemaNikola At NikoNo ratings yet

- The 400 Blows - Movie ReviewDocument2 pagesThe 400 Blows - Movie ReviewPoorviNo ratings yet

- 72 - Thorat Khushi - Final SynopsisDocument5 pages72 - Thorat Khushi - Final Synopsiskhushi thoratNo ratings yet

- En Wikipedia Org Wiki D K PattammalDocument8 pagesEn Wikipedia Org Wiki D K PattammalBandi BablooNo ratings yet

- Fascinating Machismo Toward An Unmasking of Heterosexual Masculinityin Arturo Ripstein's El Lugar Sin LímitesDocument23 pagesFascinating Machismo Toward An Unmasking of Heterosexual Masculinityin Arturo Ripstein's El Lugar Sin LímitesDiego Pérez HernándezNo ratings yet

- Indovision TV - PackagesDocument5 pagesIndovision TV - Packagesdunc4ntNo ratings yet

- Online Test ResultsDocument48 pagesOnline Test ResultsNaveen Kumar PagadalaNo ratings yet

- Quarter 3 Self-Learning Module 2 Media-Based Arts and Designs in The Philippines-Film-numberedDocument30 pagesQuarter 3 Self-Learning Module 2 Media-Based Arts and Designs in The Philippines-Film-numberedUricca Mari Briones SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Do You Know My Town?: Swimming Pool Town HallDocument1 pageDo You Know My Town?: Swimming Pool Town Hallsonia martinsNo ratings yet

- Srno. Village Name Habitation Name Family Id Family Head Gram Panchayat NameDocument24 pagesSrno. Village Name Habitation Name Family Id Family Head Gram Panchayat NamePhaNt0m GamingNo ratings yet

- P.R.No. Vs NameDocument96 pagesP.R.No. Vs NamekinananthaNo ratings yet

- Michael Snow Life and WorkDocument94 pagesMichael Snow Life and Workactua1No ratings yet

- Oriental All CandidateDocument11 pagesOriental All Candidateai terminalNo ratings yet

- Nodal OfficersDocument2 pagesNodal Officershkpatel9No ratings yet

- All Banks Pan India Contact NumbersDocument96 pagesAll Banks Pan India Contact NumbersAshwani KumarNo ratings yet

- Total Result 1308Document223 pagesTotal Result 1308Maroti ChandankhedeNo ratings yet

- Govinda The Lovable HeroDocument3 pagesGovinda The Lovable Herocarolyne28No ratings yet

- Let-Me-Introduce-Myself-For-Adults-Fun-Activities-Games - 17063 ResueltoDocument1 pageLet-Me-Introduce-Myself-For-Adults-Fun-Activities-Games - 17063 ResueltoLaura Daniela Di NinnoNo ratings yet

- CSC DataDocument8 pagesCSC DataPreeti JaiswalNo ratings yet

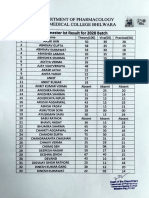

- Semester 1st Result For Batch 2020Document5 pagesSemester 1st Result For Batch 2020Divanshu GauravNo ratings yet

- LeadsDocument18 pagesLeadsPUNIT PRAJAPATINo ratings yet

- Threestooges PDFDocument66 pagesThreestooges PDFMaria Aiza Maniwang Calumba100% (1)