Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Albert Schweitzer - Wikipedia

Albert Schweitzer - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

xinooxCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Albert Schweitzer - Wikipedia

Albert Schweitzer - Wikipedia

Uploaded by

xinooxCopyright:

Available Formats

Albert Schweitzer

Article Talk

For the film, see Albert Schweitzer (film). For

the American artist, see Albert Schweitzer

(artist).

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer OM

(German: [ˈalbɛʁt ˈʃvaɪ̯t͡ sɐ] ⓘ; 14 January

1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian

polymath. He was a theologian, organist,

musicologist, writer, humanitarian,

philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran

minister, Schweitzer challenged both the

secular view of Jesus as depicted by the

historical-critical method current at this

time, as well as the traditional Christian view.

His contributions to the interpretation of

Pauline Christianity concern the role of Paul's

mysticism of "being in Christ" as primary and

the doctrine of justification by faith as

secondary.

The Reverend

Albert Schweitzer

OM

Schweitzer in 1955

Born 14 January 1875

Kaysersberg, Alsace–

Lorraine,

German Empire

Died 4 September 1965

(aged 90)

Lambaréné, Gabon

Citizenship Germany (until 1919)

France (from 1919)

Alma mater University of

Strasbourg

Known for Quest for the

historical Jesus

Reverence for Life

Consistent

"thorough-going"

eschatology

(posthumously)

Spouse Helene Bresslau

(m. 1912; died 1957)

Awards Goethe Prize (1928)

Nobel Peace Prize

(1952)

James Cook Medal

(1959)

Scientific career

Fields Medicine ·

musicology ·

philosophy · theology

Doctoral advisor Theobald Ziegler

Heinrich Julius

Holtzmann

Robert

Wollenberg [de]

He received the 1952 Nobel Peace Prize for

his philosophy of "Reverence for Life",[1]

becoming the eighth Frenchman to be

awarded that prize. His philosophy was

expressed in many ways, but most famously

in founding and sustaining the Hôpital Albert

Schweitzer in Lambaréné, French Equatorial

Africa (now Gabon). As a music scholar and

organist, he studied the music of German

composer Johann Sebastian Bach and

influenced the Organ Reform Movement

(Orgelbewegung).

Early years

Music

Theology

Medicine

Schweitzer's views

Colonialism

Schweitzer considered his work as a medical

missionary in Africa to be his response to

Jesus' call to become "fishers of men".

Who can describe the injustice

and cruelties that in the course

of centuries they [the coloured

peoples] have suffered at the

hands of Europeans?... If a

record could be compiled of all

that has happened between the

white and the coloured races, it

would make a book containing

numbers of pages which the

reader would have to turn over

unread because their contents

would be too horrible.

Schweitzer was one of colonialism's harshest

critics. In a sermon that he preached on 6

January 1905, before he had told anyone of

his plans to dedicate the rest of his life to

work as a physician in Africa, he said:[63]

Our culture divides people into

two classes: civilized men, a title

bestowed on the persons who do

the classifying; and others, who

have only the human form, who

may perish or go to the dogs for

all the 'civilized men' care.

Oh, this 'noble' culture of ours!

It speaks so piously of human

dignity and human rights and

then disregards this dignity and

these rights of countless

millions and treads them

underfoot, only because they

live overseas or because their

skins are of different colour or

because they cannot help

themselves. This culture does

not know how hollow and

miserable and full of glib talk it

is, how common it looks to those

who follow it across the seas and

see what it has done there, and

this culture has no right to speak

of personal dignity and human

rights...

I will not enumerate all the

crimes that have been

committed under the pretext of

justice. People robbed native

inhabitants of their land, made

slaves of them, let loose the

scum of mankind upon them.

Think of the atrocities that were

perpetrated upon people made

subservient to us, how

systematically we have ruined

them with our alcoholic 'gifts',

and everything else we have

done... We decimate them, and

then, by the stroke of a pen, we

take their land so they have

nothing left at all...

If all this oppression and all this

sin and shame are perpetrated

under the eye of the German

God, or the American God, or

the British God, and if our states

do not feel obliged first to lay

aside their claim to be

'Christian'—then the name of

Jesus is blasphemed and made a

mockery. And the Christianity of

our states is blasphemed and

made a mockery before those

poor people. The name of Jesus

has become a curse, and our

Christianity—yours and mine—

has become a falsehood and a

disgrace, if the crimes are not

atoned for in the very place

where they were instigated. For

every person who committed an

atrocity in Jesus' name,

someone must step in to help in

Jesus' name; for every person

who robbed, someone must

bring a replacement; for

everyone who cursed, someone

must bless.

And now, when you speak about

missions, let this be your

message: We must make

atonement for all the terrible

crimes we read of in the

newspapers. We must make

atonement for the still worse

ones, which we do not read

about in the papers, crimes that

are shrouded in the silence of

the jungle night ...

Paternalism

Schweitzer was nonetheless still sometimes

accused of being paternalistic in his attitude

towards Africans.[64] For instance, he

thought that Gabonese independence came

too early, without adequate education or

accommodation to local circumstances.

Edgar Berman quotes Schweitzer as having

said in 1960, "No society can go from the

primeval directly to an industrial state

without losing the leavening that time and an

agricultural period allow."[65] Schweitzer

believed dignity and respect must be

extended to blacks, while also sometimes

characterizing them as children.[66] He

summarized his views on European-African

relations by saying "With regard to the

negroes, then, I have coined the formula: 'I

am your brother, it is true, but your elder

brother.'"[66] Chinua Achebe has criticized

him for this characterization, though Achebe

acknowledges that Schweitzer's use of the

word "brother" at all was, for a European of

the early 20th century, an unusual

expression of human solidarity between

Europeans and Africans.[61] Schweitzer

eventually emended and complicated this

notion with his later statement that "The time

for speaking of older and younger brothers

has passed".[67]

American journalist John Gunther visited

Lambaréné in the 1950s and reported

Schweitzer's patronizing attitude towards

Africans. He also noted the lack of Africans

trained to be skilled workers.[68] By

comparison, his English contemporary Albert

Ruskin Cook in Uganda had been training

nurses and midwives since the 1910s, and

had published a manual of midwifery in the

local language of Luganda.[69] After three

decades in Africa, Schweitzer still depended

on Europe for nurses.[70]

Reverence for life

Later life

The Schweitzer house and

Museum at Königsfeld in the

Black Forest

After the birth of their daughter (Rhena

Schweitzer Miller), Albert's wife, Helene

Schweitzer was no longer able to live in

Lambaréné due to her health. In 1923, the

family moved to Königsfeld im Schwarzwald,

Baden-Württemberg, where he was building

a house for the family. This house is now

maintained as a Schweitzer museum.[77]

Albert Schweitzer's house at

Gunsbach, now a museum and

archive

Albert Schweitzer Memorial and

Museum in Weimar (1984)

From 1939 to 1948, he stayed in Lambaréné,

unable to go back to Europe because of the

war. Three years after the end of World War

II, in 1948, he returned for the first time to

Europe and kept travelling back and forth

(and once to the US) as long as he was able.

During his return visits to his home village of

Gunsbach, Schweitzer continued to make

use of the family house, which after his death

became an archive and museum to his life

and work. His life was portrayed in the 1952

movie Il est minuit, Docteur Schweitzer,

starring Pierre Fresnay as Albert Schweitzer

and Jeanne Moreau as his nurse Marie.

Schweitzer inspired actor Hugh O'Brian when

O'Brian visited in Africa. O'Brian returned to

the United States and founded the Hugh

O'Brian Youth Leadership Foundation

(HOBY).

Albert Schweitzer

Monument in Wagga

Wagga, Australia

Schweitzer was awarded the Nobel Peace

Prize of 1952,[78] accepting the prize with

the speech, "The Problem of Peace".[79] With

the $33,000 prize money, he started the

leprosarium at Lambaréné.[14] From 1952

until his death he worked against nuclear

tests and nuclear weapons with Albert

Einstein, Otto Hahn and Bertrand Russell. In

1957 and 1958, he broadcast four speeches

over Radio Oslo which were published in

Peace or Atomic War. In 1957, Schweitzer

was one of the founders of The Committee

for a Sane Nuclear Policy. On 23 April 1957,

Schweitzer made his "Declaration of

Conscience" speech; it was broadcast to the

world over Radio Oslo, pleading for the

abolition of nuclear weapons. His speech

ended, "The end of further experiments with

atom bombs would be like the early sunrays

of hope which suffering humanity is longing

for."[80]

Weeks prior to his death, an American film

crew was allowed to visit Schweitzer and Drs.

Muntz and Friedman, both Holocaust

survivors, to record his work and daily life at

the hospital. The film The Legacy of Albert

Schweitzer, narrated by Henry Fonda, was

produced by Warner Brothers and aired

once. It resides in their vault today in

deteriorating condition. Although several

attempts have been made to restore and re-

air the film, all access has been denied.[81]

In 1955, he was made an honorary member

of the Order of Merit (OM) by Queen

Elizabeth II.[82] He was also a chevalier of the

Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint

Lazarus of Jerusalem.

Schweitzer's grave in

Lambaréné, marked by a cross

he made himself.

Schweitzer died on 4 September 1965 at his

beloved hospital in Lambaréné, now in

independent Gabon. His grave, on the banks

of the Ogooué River, is marked by a cross he

made himself.

His cousin Anne-Marie Schweitzer Sartre

was the mother of Jean-Paul Sartre. Her

father, Charles Schweitzer, was the older

brother of Albert Schweitzer's father, Louis

Théophile.[83][better source needed]

Schweitzer is often cited in vegetarian

literature as being an advocate of

vegetarianism in his later years.[84][85][86]

Schweitzer was not a vegetarian in his earlier

life. For example, in 1950, biographer

Magnus C. Ratter commented that

Schweitzer never "commit[ted] himself to

the anti-vivisection, vegetarian, or pacifist

positions, though his thought leads in this

direction".[87] Biographer James Bentley has

written that Schweitzer became a vegetarian

after his wife's death in 1957 and he was

"living almost entirely on lentil soup".[88] In

contrast to this, historian David N. Stamos

has written that Schweitzer was not a

vegetarian in his personal life nor imposed it

on his missionary hospital but he did help

animals and was opposed to hunting.[89]

Stamos noted that Schweitzer held the view

that evolution ingrained humans with an

instinct for meat so it was useless in trying to

deny it.[89]

The Albert Schweitzer Fellowship was

founded in 1940 by Schweitzer to unite US

supporters in filling the gap in support for his

Hospital when his European supply lines

were cut off by war, and continues to support

the Lambaréné Hospital today. Schweitzer

considered his ethic of Reverence for Life,

not his hospital, his most important legacy,

saying that his Lambaréné Hospital was just

"my own improvisation on the theme of

Reverence for Life. Everyone can have their

own Lambaréné". Today ASF helps large

numbers of young Americans in health-

related professional fields find or create

"their own Lambaréné" in the US or

internationally. ASF selects and supports

nearly 250 new US and Africa Schweitzer

Fellows each year from over 100 of the

leading US schools of medicine, nursing,

public health, and every other field with

some relation to health (including music, law,

and divinity). The peer-supporting lifelong

network of "Schweitzer Fellows for Life"

numbered over 2,000 members in 2008, and

is growing by nearly 1,000 every four years.

Nearly 150 of these Schweitzer Fellows have

served at the Hospital in Lambaréné, for

three-month periods during their last year of

medical school.[90]

Schweitzer eponyms

Schweitzer's writings and life are often

quoted,[91] resulting in a number of

eponyms, such as the 'Schweitzer technique'

(discussed below), and the 'Schweitzer

effect'. The 'Schweitzer effect' refers to his

statement that 'Example is not the main thing

in influencing others; it is the only thing'.[91]

This eponym is used in medical education to

highlight the relationship between lived

experience/example and medical students'

opinions on professional behaviours.[92]

International Albert

Schweitzer Prize

Sound recordings

Portrayals

Bibliography

See also

Notes

1. ^ He officiated at the wedding of Theodor

Heuss (later the first President of West

Germany) in 1908.[29][30][31][32][33]

2. ^ Schweitzer's Bach recordings are usually

identified with reference to the Peters Edition

of the Organ-works in 9 volumes, edited by

Friedrich Konrad Griepenkerl and Ferdinand

August Roitzsch, in the form revised by

Hermann Keller.

References

Further reading

External links

Last edited 6 days ago by Citation bot

Content is available under CC BY-SA 4.0

unless otherwise noted.

Terms of Use • Privacy policy • Desktop

You might also like

- Kuji-Kiri and MajutsuDocument85 pagesKuji-Kiri and MajutsuVistor Corts100% (8)

- Exemption From Vaccine MandateDocument2 pagesExemption From Vaccine MandateAlberto100% (8)

- (Social Science Classics) Everett C. Hughes - David Riesman, Howard S. Becker (Eds.) - The Sociological Eye - Selected Papers-Transaction Publishers (1993) PDFDocument607 pages(Social Science Classics) Everett C. Hughes - David Riesman, Howard S. Becker (Eds.) - The Sociological Eye - Selected Papers-Transaction Publishers (1993) PDFDiogo Silva CorreaNo ratings yet

- The Wreck of Western Culture: humanism revisitedFrom EverandThe Wreck of Western Culture: humanism revisitedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Albert Einstein, The Human Side: Glimpses from His ArchivesFrom EverandAlbert Einstein, The Human Side: Glimpses from His ArchivesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (7)

- Forty Rules of LoveDocument41 pagesForty Rules of Lovetango4885% (20)

- 3 Disciple - The HAND Illustration Expanded - EDocument2 pages3 Disciple - The HAND Illustration Expanded - EJermias Ravi LenahatuNo ratings yet

- FACT 0TheEthicsofAlbertSchweitzer.3Document10 pagesFACT 0TheEthicsofAlbertSchweitzer.3Morosan ValentinNo ratings yet

- Death of Ivan IlyichDocument47 pagesDeath of Ivan IlyichEren Yamak (Student)No ratings yet

- 4.AlbertSchweitzer OutOfMyLifeThought AnAutobiographyDocument294 pages4.AlbertSchweitzer OutOfMyLifeThought AnAutobiographyIoan CretaNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Albert Schweitzer As An Inspiration For Global EthicsDocument19 pagesThe Ethics of Albert Schweitzer As An Inspiration For Global EthicsRamón Díaz-AlersiNo ratings yet

- Auschwitz Concentration Camp ThesisDocument5 pagesAuschwitz Concentration Camp Thesisfexschhld100% (1)

- Unit10 Meaning-Of-life Summer2014 RevDocument7 pagesUnit10 Meaning-Of-life Summer2014 RevTT NNNo ratings yet

- Albert Camus - WikipediaDocument17 pagesAlbert Camus - WikipediaGNo ratings yet

- Who Was André Chouraqui RevisedDocument9 pagesWho Was André Chouraqui RevisedMurray WatsonNo ratings yet

- Mistaken Identities CultureDocument17 pagesMistaken Identities CultureDaniel Orizaga DoguimNo ratings yet

- Elie Wiesel BiographyDocument1 pageElie Wiesel Biographyapi-252344608No ratings yet

- Planet Auschwitz: Holocaust Representation in Science Fiction and Horror Film and TelevisionFrom EverandPlanet Auschwitz: Holocaust Representation in Science Fiction and Horror Film and TelevisionNo ratings yet

- Auschwitz Thesis StatementDocument8 pagesAuschwitz Thesis Statementmariaparkslasvegas100% (2)

- George Steiner's Jewish ProblemDocument25 pagesGeorge Steiner's Jewish Problemapi-26091012No ratings yet

- ISP - 102 Albert Schweitzer ReportDocument2 pagesISP - 102 Albert Schweitzer ReportangelaNo ratings yet

- Albert CamusDocument18 pagesAlbert CamustriciaelNo ratings yet

- Elie WieselDocument14 pagesElie WieselFhadzralyn Lumabao Aidil. KaranainNo ratings yet

- 2150 9298 Arrs110102Document30 pages2150 9298 Arrs110102Athirah AffendiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper AuschwitzDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Auschwitzaferauplg100% (1)

- Jews Must Live by Samuel Roth - PDF RoomDocument349 pagesJews Must Live by Samuel Roth - PDF RoomDavid LealNo ratings yet

- Religions 03 00600Document46 pagesReligions 03 00600MiguelNo ratings yet

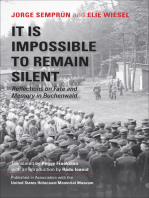

- It Is Impossible to Remain Silent: Reflections on Fate and Memory in BuchenwaldFrom EverandIt Is Impossible to Remain Silent: Reflections on Fate and Memory in BuchenwaldNo ratings yet

- Albert Schweitzer - Research ReportDocument3 pagesAlbert Schweitzer - Research ReportGuNo ratings yet

- Queer Jewish Lives Between Central Europe and Mandatory Palestine: Biographies and GeographiesFrom EverandQueer Jewish Lives Between Central Europe and Mandatory Palestine: Biographies and GeographiesNo ratings yet

- Roth Samuel - Jews Must LiveDocument196 pagesRoth Samuel - Jews Must LivejoseliraNo ratings yet

- Food and Fooways in Extremis, FoodandFoodways, 1999, VoL8 (L), PP, 1-32Document32 pagesFood and Fooways in Extremis, FoodandFoodways, 1999, VoL8 (L), PP, 1-32Božidar JezernikNo ratings yet

- Night Student GuideDocument14 pagesNight Student Guideapi-328715247No ratings yet

- Bolshevism From Moses To Lenin: Dietrich EckartDocument31 pagesBolshevism From Moses To Lenin: Dietrich EckartWillie JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Existentialism: Literature and PhilosophyDocument40 pagesIntroduction To Existentialism: Literature and PhilosophyFitz BaniquedNo ratings yet

- On the Eve: The Jews of Europe Before the Second World WarFrom EverandOn the Eve: The Jews of Europe Before the Second World WarRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (15)

- Anthropology of Death PDFDocument4 pagesAnthropology of Death PDFRaluca BobiaNo ratings yet

- Elie Wiesel Introduction PowerpointDocument33 pagesElie Wiesel Introduction PowerpointSriramNo ratings yet

- Hitler and The Secret SocietiesDocument14 pagesHitler and The Secret SocietiesDavid Ruv Ifasowunmi Awokoya OyekanmiNo ratings yet

- Judging 'Privileged' Jews: Holocaust Ethics, Representation, and the 'Grey Zone'From EverandJudging 'Privileged' Jews: Holocaust Ethics, Representation, and the 'Grey Zone'No ratings yet

- CannibalismDocument5 pagesCannibalismFreeman SalemNo ratings yet

- We Are Here: talking with Australia's oldest Holocaust survivorsFrom EverandWe Are Here: talking with Australia's oldest Holocaust survivorsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Resisting the Bonhoeffer Brand: A Life ReconsideredFrom EverandResisting the Bonhoeffer Brand: A Life ReconsideredRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Pensadores de La Memoria.Document7 pagesPensadores de La Memoria.Gisela Rodriguez GomezNo ratings yet

- Born Atheist, Buried ChristianDocument3 pagesBorn Atheist, Buried ChristianMariusNo ratings yet

- Broadcast Yourself. 23 Jan. 2009. Web. 29 Mar. 2011Document4 pagesBroadcast Yourself. 23 Jan. 2009. Web. 29 Mar. 2011gw0492151No ratings yet

- The André Bazin Reader - AumontDocument43 pagesThe André Bazin Reader - AumontTimothy BarnardNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography of ' The Stranger ' by Albert Camus.Document6 pagesAnnotated Bibliography of ' The Stranger ' by Albert Camus.minogeneNo ratings yet

- Karl Heinrich UlrichsDocument333 pagesKarl Heinrich UlrichsErckk Santos100% (2)

- Dơnload Herman Melville Leon Howard Full ChapterDocument24 pagesDơnload Herman Melville Leon Howard Full Chapteruetaandyna100% (3)

- Curse & GiftDocument21 pagesCurse & GiftBegüm GüvenNo ratings yet

- George Orwell, Geoffrey Chaucer, and Anti-SemitismDocument5 pagesGeorge Orwell, Geoffrey Chaucer, and Anti-SemitismJack OpieNo ratings yet

- The Holocaust and Philosophy - Emil FackenheimDocument11 pagesThe Holocaust and Philosophy - Emil FackenheimElis SimsonNo ratings yet

- (WA Ed.) Impeachment of ManDocument144 pages(WA Ed.) Impeachment of ManZelthirNo ratings yet

- A Biographical Dictionary of Freethinkers of All Ages and NationsFrom EverandA Biographical Dictionary of Freethinkers of All Ages and NationsNo ratings yet

- Islam Dan Dialog Antar Kebudayaan (Studi Dinamika Islam Di Dunia Barat) Dedi Wahyudi Dan Rahayu Fitri ASDocument24 pagesIslam Dan Dialog Antar Kebudayaan (Studi Dinamika Islam Di Dunia Barat) Dedi Wahyudi Dan Rahayu Fitri ASZona NyamanNo ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument1 pageReflectionSimon Marquis LUMBERANo ratings yet

- Juli AgustusDocument3 pagesJuli Agustusnanda silitongaNo ratings yet

- Robinson Crusoe EverymanDocument4 pagesRobinson Crusoe EverymanPrerna GuhaNo ratings yet

- 73 Indian House Names On God in SanskritDocument2 pages73 Indian House Names On God in SanskritPiyu AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Full Download Financial Accounting Ifrs 3rd Edition Weygandt Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesFull Download Financial Accounting Ifrs 3rd Edition Weygandt Solutions Manualjames0vpamat97% (33)

- 99 Surah ZilzalDocument5 pages99 Surah Zilzalamjad_emailNo ratings yet

- Santo Rosario LatinDocument7 pagesSanto Rosario LatinAgus OtondoNo ratings yet

- Final Script - 18-7 - UpdatedDocument4 pagesFinal Script - 18-7 - Updatedm_sachu100% (1)

- Pidato Bahasa Ingris Hormat Kepada Orang Tua Dan GuruDocument1 pagePidato Bahasa Ingris Hormat Kepada Orang Tua Dan Guruyogaegy01No ratings yet

- Account of Snana Yatra 2012Document1 pageAccount of Snana Yatra 2012gopalguruNo ratings yet

- Naksibendi AwradDocument1 pageNaksibendi AwradHshhdhd ZghwjdhhsxNo ratings yet

- Ire Paper 1 O-Level Pre Islamic Arabia Summarised PointsDocument119 pagesIre Paper 1 O-Level Pre Islamic Arabia Summarised PointsJerry Jason80% (5)

- 1 PBDocument19 pages1 PBAnak DesaNo ratings yet

- Snakes and MysticismDocument9 pagesSnakes and Mysticismcharan74100% (1)

- Prayer For Alumni NightDocument1 pagePrayer For Alumni NightShefferd BernalesNo ratings yet

- It's: A Weaving of Words (Part The IV)Document40 pagesIt's: A Weaving of Words (Part The IV)Caleb Alan Kestner100% (33)

- The Secret of Happiness The Fifteen Prayers As Revealed by OUR LORD To ST. BRIDGET in The CHURCH of ST. PAUL in ROMEDocument12 pagesThe Secret of Happiness The Fifteen Prayers As Revealed by OUR LORD To ST. BRIDGET in The CHURCH of ST. PAUL in ROMEJESUS IS RETURNING DURING OUR GENERATION100% (4)

- Instant Download Structures 7th Edition Schodek Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Structures 7th Edition Schodek Solutions Manual PDF Full Chapteranthonyhollowayxqkfprdjew100% (10)

- Notre Dame PrayersDocument4 pagesNotre Dame PrayersChhavi SukanyaNo ratings yet

- Teks Latin Maulid Adh DhiyaDocument10 pagesTeks Latin Maulid Adh DhiyaHamba AllahNo ratings yet

- 10 Form TestsDocument5 pages10 Form TeststarammasterNo ratings yet

- Jesus Is Better: Matt Taylor Matt TaylorDocument2 pagesJesus Is Better: Matt Taylor Matt Taylorruth maddaloraNo ratings yet

- GUBbi BanbwaDocument114 pagesGUBbi BanbwaMarc PhilipNo ratings yet

- Allah's Names Their SignificanceDocument8 pagesAllah's Names Their Significanceapi-268703820% (1)

- EVANGELISM in ThadouDocument15 pagesEVANGELISM in Thadouharry misaoNo ratings yet