Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Keats’s Odes To Autumn Summary & Analysis Spark…

Keats’s Odes To Autumn Summary & Analysis Spark…

Uploaded by

jamalevanescence123Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Keats’s Odes To Autumn Summary & Analysis Spark…

Keats’s Odes To Autumn Summary & Analysis Spark…

Uploaded by

jamalevanescence123Copyright:

Available Formats

Keats’s Odes

John Keats

Study Guide

Summary Literary Devices Essays Fur

Summary

To Autumn

Summary To Autumn

Summary

Keats’s speaker opens his first stanza by

addressing Autumn, describing its abundance

and its intimacy with the sun, with whom

Autumn ripens fruits and causes the late

flowers to bloom. In the second stanza, the

speaker describes the figure of Autumn as a

female goddess, often seen sitting on the

granary floor, her hair “soft-lifted” by the wind,

and often seen sleeping in the fields or

watching a cider-press squeezing the juice

from apples. In the third stanza, the speaker

tells Autumn not to wonder where the songs of

spring have gone, but instead to listen to her

own music. At twilight, the “small gnats” hum

among the "the river sallows," or willow trees,

lifted and dropped by the wind, and “full-grown

lambs” bleat from the hills, crickets sing, robins

whistle from the garden, and swallows,

gathering for their coming migration, sing from

the skies.

Form

Like the “Ode on Melancholy,” “To Autumn” is

written in a three-stanza structure with a

variable rhyme scheme. Each stanza is eleven

lines long (as opposed to ten in “Melancholy”,

and each is metered in a relatively precise

iambic pentameter. In terms of both thematic

organization and rhyme scheme, each stanza is

divided roughly into two parts. In each stanza,

the first part is made up of the first four lines of

the stanza, and the second part is made up of

the last seven lines. The first part of each

stanza follows an ABAB rhyme scheme, the

first line rhyming with the third, and the second

line rhyming with the fourth. The second part of

each stanza is longer and varies in rhyme

scheme: The first stanza is arranged CDEDCCE,

and the second and third stanzas are arranged

CDECDDE. (Thematically, the first part of each

stanza serves to define the subject of the

stanza, and the second part o!ers room for

musing, development, and speculation on that

subject; however, this thematic division is only

very general.)

Themes

In both its form and descriptive surface, “To

Autumn” is one of the simplest of Keats’s odes.

There is nothing confusing or complex in

Keats’s paean to the season of autumn, with its

fruitfulness, its flowers, and the song of its

swallows gathering for migration. The

extraordinary achievement of this poem lies in

its ability to suggest, explore, and develop a

rich abundance of themes without ever ru"ing

its calm, gentle, and lovely description of

autumn. Where “Ode on Melancholy” presents

itself as a strenuous heroic quest, “To Autumn”

is concerned with the much quieter activity of

daily observation and appreciation. In this

quietude, the gathered themes of the

preceding odes find their fullest and most

beautiful expression.

“To Autumn” takes up where the other odes

leave o!. Like the others, it shows Keats’s

speaker paying homage to a particular

goddess—in this case, the deified season of

Autumn. The selection of this season implicitly

takes up the other odes’ themes of temporality,

mortality, and change: Autumn in Keats’s ode is

a time of warmth and plenty, but it is perched

on the brink of winter’s desolation, as the bees

enjoy “later flowers,” the harvest is gathered

from the fields, the lambs of spring are now

“full grown,” and, in the final line of the poem,

the swallows gather for their winter migration.

The understated sense of inevitable loss in that

final line makes it one of the most moving

moments in all of poetry; it can be read as a

simple, uncomplaining summation of the entire

human condition.

Despite the coming chill of winter, the late

warmth of autumn provides Keats’s speaker

with ample beauty to celebrate: the cottage

and its surroundings in the first stanza, the

agrarian haunts of the goddess in the second,

and the locales of natural creatures in the third.

Keats’s speaker is able to experience these

beauties in a sincere and meaningful way

because of the lessons he has learned in the

previous odes: He is no longer indolent, no

longer committed to the isolated imagination

(as in “Psyche”), no longer attempting to escape

the pain of the world through ecstatic rapture

(as in “Nightingale”), no longer frustrated by the

attempt to eternalize mortal beauty or subject

eternal beauty to time (as in “Urn”), and no

longer able to frame the connection of

pleasure and the sorrow of loss only as an

imaginary heroic quest (as in “Melancholy”).

In “To Autumn,” the speaker’s experience of

beauty refers back to earlier odes (the

swallows recall the nightingale; the fruit recalls

joy’s grape; the goddess drowsing among the

poppies recalls Psyche and Cupid lying in the

grass), but it also recalls a wealth of earlier

poems. Most importantly, the image of Autumn

winnowing and harvesting (in a sequence of

odes often explicitly about creativity) recalls an

earlier Keats poem in which the activity of

harvesting is an explicit metaphor for artistic

creation. In his sonnet.

When I have fears that I may

cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my

teeming brain,

Before high-piled books, in

charactry,

Hold like rich garners the full

ripen’d grain...

In this poem, the act of creation is pictured as a

kind of self-harvesting; the pen harvests the

fields of the brain, and books are filled with the

resulting “grain.” In “To Autumn,” the metaphor is

developed further; the sense of coming loss

that permeates the poem confronts the sorrow

underlying the season’s creativity. When

Autumn’s harvest is over, the fields will be bare,

the swaths with their “twined flowers” cut

down, the cider-press dry, the skies empty. But

the connection of this harvesting to the

seasonal cycle softens the edge of the tragedy.

In time, spring will come again, the fields will

grow again, and the birdsong will return. As the

speaker knew in “Melancholy,” abundance and

loss, joy and sorrow, song and silence are as

intimately connected as the twined flowers in

the fields. What makes “To Autumn” beautiful is

that it brings an engagement with that

connection out of the realm of mythology and

fantasy and into the everyday world. The

development the speaker so strongly resisted

in “Indolence” is at last complete: He has

learned that an acceptance of mortality is not

destructive to an appreciation of beauty and

has gleaned wisdom by accepting the passage

of time.

Previous section

Popular pages: Keats’s Odes

Themes

LITERARY DEVICES

Take a Study Break

QUIZ: Is This a Taylor Swift

Lyric or a Quote by Edgar

Allan Poe?

The 7 Most Embarrassing

Proposals in Literature

The 6 Best and Worst TV

Show Adaptations of Books

QUIZ: Which Greek God Are

You?

Sign up for our latest news and

updates!

By entering your email address you agree to

receive emails from SparkNotes and verify that

you are over the age of 13. You can view our

Privacy Policy here. Unsubscribe from our

emails at any time.

First Name

Last Name

Sign Up

SparkNotes—the stress-free way

to a better GPA

Quick Links

No Fear Shakespeare

Literature Guides

Other Subjects

Blog

Teacher’s Handbook

Premium Study Tools

SparkNotes PLUS

Sign Up

Log In

PLUS Help

More

Help

How to Cite SparkNotes

How to Write Literary Analysis

About

Contact Us

Copyright © 2023 SparkNotes LLC

Terms of Use | Privacy | Cookie Policy

Do Not Sell My Personal Information

Privacy - Terms

You might also like

- Sound and SenseDocument86 pagesSound and SenseKin Barkly60% (5)

- Heather Love - Compulsory Happiness and Queer ExistenceDocument14 pagesHeather Love - Compulsory Happiness and Queer ExistenceEduardoMattioNo ratings yet

- Poem Essay Ego TrippingDocument4 pagesPoem Essay Ego Trippingapi-278729765No ratings yet

- New Wordpad DocumentDocument21 pagesNew Wordpad DocumentKosovare Berisha GrepiNo ratings yet

- Stele Di Sehetepibre (Abydos Peker)Document6 pagesStele Di Sehetepibre (Abydos Peker)tormael_56No ratings yet

- Suspense EssayDocument3 pagesSuspense Essayapi-358049726No ratings yet

- To Autumn2Document3 pagesTo Autumn2springsimoNo ratings yet

- Ode To Autumn ThesisDocument7 pagesOde To Autumn Thesisglzhcoaeg100% (2)

- How To Write A Poetry EssayDocument3 pagesHow To Write A Poetry Essayzaenal mfdNo ratings yet

- Ways With Words PDFDocument10 pagesWays With Words PDFFavaz Mk100% (1)

- To AutumDocument16 pagesTo AutumAnthony ChanNo ratings yet

- Shelley Vs KeatsDocument7 pagesShelley Vs KeatsIrfan Sahito100% (1)

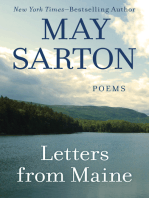

- The Poetry of May Sarton Volume Two: A Durable Fire, A Grain of Mustard Seed, and A Private MythologyFrom EverandThe Poetry of May Sarton Volume Two: A Durable Fire, A Grain of Mustard Seed, and A Private MythologyNo ratings yet

- Poetry Power PointDocument24 pagesPoetry Power PointMariecel DaciaNo ratings yet

- Ode To AutumnDocument7 pagesOde To Autumnamnaarabi67% (3)

- PoetryDocument8 pagesPoetryjamielou gutierrezNo ratings yet

- Ode On A Grecian UrnDocument13 pagesOde On A Grecian UrnMuhammad AbidNo ratings yet

- Keats' PoetryDocument12 pagesKeats' PoetryMuhammad IrfanNo ratings yet

- New Criticism-WPS OfficeDocument4 pagesNew Criticism-WPS OfficeMuhammad AdnanNo ratings yet

- Advanced Contemporary Lit CritDocument5 pagesAdvanced Contemporary Lit CritGem Audrey AlicayaNo ratings yet

- Assignment LiteratureDocument13 pagesAssignment LiteratureTashfeen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 73 ThesisDocument4 pagesSonnet 73 Thesislupitavickreypasadena100% (2)

- The Poetry of May Sarton Volume One: Letters from Maine, Inner Landscape, and Halfway to SilenceFrom EverandThe Poetry of May Sarton Volume One: Letters from Maine, Inner Landscape, and Halfway to SilenceNo ratings yet

- 27 Poetic DevicesDocument10 pages27 Poetic DevicesRajesh SannanNo ratings yet

- Ode To A NightingleDocument5 pagesOde To A NightingleNimra BaigNo ratings yet

- POETRY Lesson - MagDocument12 pagesPOETRY Lesson - MagZoe The PoetNo ratings yet

- Ode To A NightingaleDocument6 pagesOde To A Nightingalescribdguru2No ratings yet

- What Is Poetry?: Poetes Which Means "Maker." PoetryDocument5 pagesWhat Is Poetry?: Poetes Which Means "Maker." Poetryhey kumarieNo ratings yet

- John KeatsDocument7 pagesJohn KeatsAlinaNo ratings yet

- John Keats: Ode To A NightingaleDocument7 pagesJohn Keats: Ode To A Nightingalesaeedfathy4455No ratings yet

- Research Paper Romantic PoetryDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Romantic Poetrywgaaobsif100% (1)

- Charles Pierre BaudelaireDocument6 pagesCharles Pierre BaudelaireCecile Yul BulanteNo ratings yet

- Write A Critical Appreciation of The Poem "To Autumn"Document3 pagesWrite A Critical Appreciation of The Poem "To Autumn"Ac100% (1)

- Ode To AutumnDocument3 pagesOde To AutumnAdya Singh67% (9)

- A Vagabond SongDocument4 pagesA Vagabond SongLiLiana DewiNo ratings yet

- Emily Dickinson AnalysisDocument6 pagesEmily Dickinson AnalysisNicolas HuyghebaertNo ratings yet

- Ode To AutumnDocument2 pagesOde To AutumnMirza Naveed Akhtar100% (1)

- The Tiger: William BlakeDocument19 pagesThe Tiger: William BlakeMohammad Suleiman AlzeinNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement For Tears Idle TearsDocument7 pagesThesis Statement For Tears Idle Tearsaflnzraiaaetew100% (2)

- John Keats Was Born in LondonDocument12 pagesJohn Keats Was Born in Londonankank73No ratings yet

- Introduction To PoetryDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Poetryibrahim incikNo ratings yet

- ENG II Project (1) FOR CLASS 12 ISCDocument9 pagesENG II Project (1) FOR CLASS 12 ISCToxic Flocs100% (10)

- Ode To AutmnDocument43 pagesOde To AutmnRayeha MaryamNo ratings yet

- The Wild Swans at Coole "The Wild Swans at Coole" Summary and Analysis - GradeSaverDocument3 pagesThe Wild Swans at Coole "The Wild Swans at Coole" Summary and Analysis - GradeSaverZenith RoyNo ratings yet

- The Black Map-A New Criticism AnalysisDocument6 pagesThe Black Map-A New Criticism AnalysisxiruomaoNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Creative NonfictionDocument13 pagesModule 2 Creative NonfictionRodimar RamirezNo ratings yet

- Poetry Assgn Sem1Document8 pagesPoetry Assgn Sem1Priyanka JosephNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnet 73 ThesisDocument7 pagesShakespeare Sonnet 73 Thesiscarlapotierlafayette100% (2)

- The Wonderful World of PoetryDocument66 pagesThe Wonderful World of PoetryaljayNo ratings yet

- Poetry 21Document30 pagesPoetry 21AbirNo ratings yet

- L'expression Des Émotions - Tle - Cours Langues, Littératures Et Cultures Étrangères Anglais - KartableDocument1 pageL'expression Des Émotions - Tle - Cours Langues, Littératures Et Cultures Étrangères Anglais - KartableMarianne Emil-1051No ratings yet

- Shakespeare's Proleptic Refashioning of The Renaissance SonnetDocument15 pagesShakespeare's Proleptic Refashioning of The Renaissance SonnetJasmin MedjedovicNo ratings yet

- Unit IIIDocument13 pagesUnit IIIBiprojit DasNo ratings yet

- Final Notes RomanticDocument33 pagesFinal Notes RomanticLaiba AarzooNo ratings yet

- LiteratureDocument76 pagesLiteratureMhel FelicesNo ratings yet

- Ode To AutumnDocument3 pagesOde To AutumnTANBIR RAHAMANNo ratings yet

- Paper 1 SamplerDocument3 pagesPaper 1 SamplerHakam AbdulqaderNo ratings yet

- (Tutorial) TSLB3093 LG Arts... Topic 4 (B) Children's LiteratureDocument1 page(Tutorial) TSLB3093 LG Arts... Topic 4 (B) Children's LiteraturePavithira SivasubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Q#41 99Document72 pagesQ#41 99Eternal TrollsterNo ratings yet

- Keeping Orchids Revision NotesDocument3 pagesKeeping Orchids Revision Notesapi-236417442100% (1)

- Czeslaw MiloszDocument0 pagesCzeslaw Miloszthedukeofsantiago100% (1)

- Embracing The Duality of Human Experience Analysis of The Poem On Joy and Sorrow in The Prophet by Khalil GibranDocument2 pagesEmbracing The Duality of Human Experience Analysis of The Poem On Joy and Sorrow in The Prophet by Khalil GibranSaddman TahmidNo ratings yet

- Reading Grade 3Document44 pagesReading Grade 3Maneet Mathur100% (1)

- Spiritual Decay in The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot.Document5 pagesSpiritual Decay in The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot.Andreea M. DumitruNo ratings yet

- Elements of A StoryDocument35 pagesElements of A StoryGlenda Perucho LlacunaNo ratings yet

- Thi Qar Arts Journal: Vol 34 No.1 Jan. 2021Document19 pagesThi Qar Arts Journal: Vol 34 No.1 Jan. 2021Mu'izzudinNo ratings yet

- Love Songs in AgeDocument5 pagesLove Songs in Ageapi-438963588No ratings yet

- Secret Truths of Bhagavatam 1st EdDocument174 pagesSecret Truths of Bhagavatam 1st EdMaria Celeste Camargo Casemiro100% (1)

- Introducing : Figures of SpeechDocument71 pagesIntroducing : Figures of SpeechhazelNo ratings yet

- Notes On Translation Criticism PDFDocument5 pagesNotes On Translation Criticism PDFkovinusNo ratings yet

- Lapham S Quarterly Winter 2014 Comedy PDFDocument228 pagesLapham S Quarterly Winter 2014 Comedy PDFchiquilandia100% (2)

- The Cuckoo ReviewDocument1 pageThe Cuckoo ReviewSantiago Cubillos AcevedoNo ratings yet

- About KushtiaDocument4 pagesAbout KushtiaJahangir MiltonNo ratings yet

- Final Exam English 10Document1 pageFinal Exam English 10ReyNo ratings yet

- The Conversion: J. Neil GarciaDocument3 pagesThe Conversion: J. Neil GarciaElitiea KwonNo ratings yet

- English GRADE 7Document2 pagesEnglish GRADE 7Claudine Simeon PiñeraNo ratings yet

- Derrida's Memoirs of The BlindDocument9 pagesDerrida's Memoirs of The BlindPaul WilsonNo ratings yet

- The Donnellys EssayDocument5 pagesThe Donnellys Essayapi-277402275No ratings yet

- 05 Meg-08 PDFDocument4 pages05 Meg-08 PDFPrashant pandeyNo ratings yet

- B.A. I English HonoursDocument9 pagesB.A. I English HonoursNEHRA ANBNo ratings yet

- RIZAL FinalDocument20 pagesRIZAL FinalAhra Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Literature Assingment 1Document8 pagesIntroduction To Literature Assingment 1honeykhanNo ratings yet

- Historia Caligrafia China JapaoDocument10 pagesHistoria Caligrafia China Japaopaulo cassarNo ratings yet