Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Constructing Markets and Organizing Boundaries 1

Constructing Markets and Organizing Boundaries 1

Uploaded by

Fatoumata GayeCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Juran S Quality Planning andDocument1 pageJuran S Quality Planning andDebabrata Paul9% (11)

- Why Economics Has Been Fruitful For StrategyDocument5 pagesWhy Economics Has Been Fruitful For Strategypritesh1983No ratings yet

- Porter's Five Forces: Understand competitive forces and stay ahead of the competitionFrom EverandPorter's Five Forces: Understand competitive forces and stay ahead of the competitionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Marketing Concept NPODocument26 pagesMarketing Concept NPOKristy LeNo ratings yet

- Ambidextrous Strategies and Innovation PDFDocument9 pagesAmbidextrous Strategies and Innovation PDFLeidy SánchezNo ratings yet

- Outside in & Inside OutDocument44 pagesOutside in & Inside OutSlobodan AdzicNo ratings yet

- The Market Driven Organization: Understanding, Attracting, and Keeping Valuable CustomersFrom EverandThe Market Driven Organization: Understanding, Attracting, and Keeping Valuable CustomersNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Spitting Out The HookDocument3 pagesModule 3 Spitting Out The Hookapi-538740413No ratings yet

- Stratagic PlanningDocument6 pagesStratagic Planningseeraju143No ratings yet

- Teece Dynamic CapabilitiesDocument35 pagesTeece Dynamic CapabilitiesDiana Carolina Aguilar OlarteNo ratings yet

- IOM Internet TopicsDocument5 pagesIOM Internet TopicsOwenevan EvanowenNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 CDMDocument40 pagesUnit 5 CDMManojkumar MohanasundramNo ratings yet

- 1994 - DAY - The Capabilities of Market-Driven OrganizationsDocument17 pages1994 - DAY - The Capabilities of Market-Driven OrganizationsClóvis Teixeira FilhoNo ratings yet

- 10 1109@itmc 2013 7352658Document14 pages10 1109@itmc 2013 7352658Wilson SCKUDLAREKNo ratings yet

- 波特5力pdfDocument15 pages波特5力pdfrdtrinyNo ratings yet

- McDonald-Market Segmentation EJMDocument26 pagesMcDonald-Market Segmentation EJMmabdulazeez01100% (1)

- Rex - Research Proposal SentDocument15 pagesRex - Research Proposal SentFakir TajulNo ratings yet

- Corporate DiversificationDocument16 pagesCorporate DiversificationCẩm Anh ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Managerial EconomicsDocument9 pagesManagerial EconomicsAbhishek ModakNo ratings yet

- RBV & Foundation For A Market Segmentation TheoryDocument5 pagesRBV & Foundation For A Market Segmentation TheoryZXZXNo ratings yet

- New Venture Strategies: Transforming Caterpillars Into Butter IesDocument38 pagesNew Venture Strategies: Transforming Caterpillars Into Butter Iesbabak_200028No ratings yet

- VERNON - Dialectic ReportDocument12 pagesVERNON - Dialectic ReportCleoNo ratings yet

- BCG MatrixDocument5 pagesBCG Matrixprab990050% (2)

- MS 29Document8 pagesMS 29Rajni KumariNo ratings yet

- Introduction 130407092142 Phpapp01Document69 pagesIntroduction 130407092142 Phpapp01Pari Savla100% (1)

- 9d6e PDFDocument48 pages9d6e PDFHarika KollatiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Transformation and The Success of High Technology Companies Edward B. Roberts Mit Sloan School of Management AUGUST 1989 WP # 3066-89 BPSDocument35 pagesStrategic Transformation and The Success of High Technology Companies Edward B. Roberts Mit Sloan School of Management AUGUST 1989 WP # 3066-89 BPSHa TranNo ratings yet

- MBA 113 - Reaction Paper 7Document6 pagesMBA 113 - Reaction Paper 7Denise Katrina PerezNo ratings yet

- JohnsonDocument11 pagesJohnsonMohd NajibNo ratings yet

- Resumen RumeltDocument5 pagesResumen RumeltselerovsNo ratings yet

- Market Segmentation LilienDocument32 pagesMarket Segmentation LilienJuanGreenmanNo ratings yet

- American Marketing Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of MarketingDocument10 pagesAmerican Marketing Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of MarketingGall AnonimNo ratings yet

- Competitive Strategy of Private EquityDocument48 pagesCompetitive Strategy of Private Equityapritul3539No ratings yet

- On The Structural Dimension of Competitive StrategyDocument17 pagesOn The Structural Dimension of Competitive StrategyAus FirdausNo ratings yet

- Strategy and Performance - Asp PDFDocument5 pagesStrategy and Performance - Asp PDFJay Aubrey PinedaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityDocument38 pagesEvaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityrerereNo ratings yet

- Marketing Theory With Strategic Orientation PDFDocument12 pagesMarketing Theory With Strategic Orientation PDFNarmin Abida0% (1)

- Business Credit Solutions: Get A Credit Report Get A D&B D-U-N-S Number Monitor My Business Credit - FREE TRIAL!Document14 pagesBusiness Credit Solutions: Get A Credit Report Get A D&B D-U-N-S Number Monitor My Business Credit - FREE TRIAL!Harleen KaurNo ratings yet

- Structure & StrategyDocument4 pagesStructure & Strategyjacintavike42No ratings yet

- An IntraDocument16 pagesAn IntraUnachittranjan KumarNo ratings yet

- BB31403Document4 pagesBB31403nadiaNo ratings yet

- Thesis 234Document15 pagesThesis 234Villaflores HannaNo ratings yet

- Towards A Dynamic Theory of StrategyDocument23 pagesTowards A Dynamic Theory of StrategymirianalbertpiresNo ratings yet

- 316082Document28 pages316082Lim100% (1)

- M N V: T E E : Arketing in EW Entures Heory and Mpirical VidenceDocument38 pagesM N V: T E E : Arketing in EW Entures Heory and Mpirical Videncevk sarangdevotNo ratings yet

- 00 Day, George S. (1994) - The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58 (4), 37-52. Doi 10.1177:002224299405800404Document16 pages00 Day, George S. (1994) - The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58 (4), 37-52. Doi 10.1177:002224299405800404Andrés GómezNo ratings yet

- Herrigel. Autoparts-OEMcompetition PDFDocument35 pagesHerrigel. Autoparts-OEMcompetition PDFmateoNo ratings yet

- Miles and SnowDocument7 pagesMiles and SnowGLOBOPOINT CONSULTANTSNo ratings yet

- Table 2.1. The Evolution of Strategic ManagementDocument4 pagesTable 2.1. The Evolution of Strategic Managementanon_706827441No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial StrategiesDocument4 pagesEntrepreneurial StrategiesNyegran LauraNo ratings yet

- Sociology, pp.82:929-964Document3 pagesSociology, pp.82:929-964Nikelas TanNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Competencies For Leveraging Core Products in Global MarketsDocument14 pagesKnowledge Competencies For Leveraging Core Products in Global MarketsprandourmiNo ratings yet

- BCG and GE McKinsey Matrix QDocument12 pagesBCG and GE McKinsey Matrix QRian WallaceNo ratings yet

- EnvironmentsDocument4 pagesEnvironmentsjonas887No ratings yet

- Strategic Assets and Organizational RentDocument14 pagesStrategic Assets and Organizational RentEduardo SantocchiNo ratings yet

- Armour and TeeceDocument18 pagesArmour and Teecea20236878No ratings yet

- Revisiting Marketing's Lawlike Generalizations: Jagdish N. ShethDocument17 pagesRevisiting Marketing's Lawlike Generalizations: Jagdish N. ShethsaifulyusoffusmNo ratings yet

- StrategyDocument10 pagesStrategyAmit MishraNo ratings yet

- A Strategic Process Guide: Article Relevant To Professional 1 Management & Strategy Author: Fergus McdermottDocument4 pagesA Strategic Process Guide: Article Relevant To Professional 1 Management & Strategy Author: Fergus McdermottGodfrey MakurumureNo ratings yet

- EBS-Mba 4Document25 pagesEBS-Mba 4Mainpal YadavNo ratings yet

- Full Text 01Document40 pagesFull Text 01Kamran AliNo ratings yet

- FBM Assessment 4Document13 pagesFBM Assessment 4Benjamin DanielsNo ratings yet

- Galateanu 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.%3A Mater. Sci. Eng. 400 062009Document9 pagesGalateanu 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.%3A Mater. Sci. Eng. 400 062009Fatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- Consequences ETFDocument17 pagesConsequences ETFFatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- Constructing and Using Nascent Market LabelsDocument56 pagesConstructing and Using Nascent Market LabelsFatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- 2014ValueofValueMarketing TheoryDocument5 pages2014ValueofValueMarketing TheoryFatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- F520Document2 pagesF520Marcos AldrovandiNo ratings yet

- Chafi2009Document7 pagesChafi2009radhakrishnanNo ratings yet

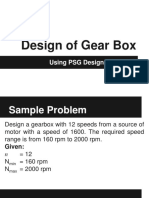

- Design of Gear BoxDocument19 pagesDesign of Gear BoxSUMIT MALUSARE100% (1)

- St. Andrew Academy Bacarra, Ilocos Norte First Grading-Grade 7 MathematicsDocument10 pagesSt. Andrew Academy Bacarra, Ilocos Norte First Grading-Grade 7 MathematicsJACOBAGONOYNo ratings yet

- Billet D Humeur 7 Reasons Why The LeidenDocument5 pagesBillet D Humeur 7 Reasons Why The LeidenjohnkalespiNo ratings yet

- 2.7 2012 Influence of Implant Neck Design and Implant-Abutment Connection Type On Peri-Implant Health. Radiological StudyDocument9 pages2.7 2012 Influence of Implant Neck Design and Implant-Abutment Connection Type On Peri-Implant Health. Radiological StudyDuilioJrNo ratings yet

- DDBMS ArchitectureDocument62 pagesDDBMS ArchitectureFranklin DorobaNo ratings yet

- Corrosión Manual NalcoDocument126 pagesCorrosión Manual NalcotinovelazquezNo ratings yet

- Zenner DiodeDocument23 pagesZenner DiodeKrishanu NaskarNo ratings yet

- Decision Trees - 2022Document49 pagesDecision Trees - 2022Soubhav ChamanNo ratings yet

- Malhotra, Garg, and Rai - Analysing The NDHM Health Data Management PolicyDocument30 pagesMalhotra, Garg, and Rai - Analysing The NDHM Health Data Management Policysimran sabharwalNo ratings yet

- TIP35/35A/35B/35C: Silicon NPN Power TransistorsDocument4 pagesTIP35/35A/35B/35C: Silicon NPN Power TransistorsJose David Perez ParadaNo ratings yet

- A Review of RhomboidityDocument10 pagesA Review of RhomboidityShrey GulatiNo ratings yet

- Astm C 1173Document4 pagesAstm C 1173Andrea Bernal JaraNo ratings yet

- Gen4 Product Manual V3.0Document118 pagesGen4 Product Manual V3.0velmusNo ratings yet

- Childhood and Growing UpDocument181 pagesChildhood and Growing UpManichander100% (2)

- 4robbins Mgmt15 PPT 02-Updated3Document46 pages4robbins Mgmt15 PPT 02-Updated3SanaaAbdelganyNo ratings yet

- AnalysisofUnder reamedPilesSubjectedtoDifferentTypesofLoadinClayeySoil 1 8 PDFDocument9 pagesAnalysisofUnder reamedPilesSubjectedtoDifferentTypesofLoadinClayeySoil 1 8 PDFAkhilesh Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Eurasian PlateDocument6 pagesEurasian PlateJoshua SalazarNo ratings yet

- Motivation: Self-Efficacy Has A Positive Impact On PerformanceDocument3 pagesMotivation: Self-Efficacy Has A Positive Impact On PerformanceVishavjeetDevganNo ratings yet

- 1SDA067399R1 xt1c 160 TMD 160 1600 3p F FDocument4 pages1SDA067399R1 xt1c 160 TMD 160 1600 3p F FBianca OlaruNo ratings yet

- Better Graphics r10 PDFDocument45 pagesBetter Graphics r10 PDFdocsmsNo ratings yet

- Purdue Engineering 2010 PDFDocument98 pagesPurdue Engineering 2010 PDFGanesh BabuNo ratings yet

- Employment News 30 September - 06 OctoberDocument39 pagesEmployment News 30 September - 06 OctoberNishant Pratap Singh100% (1)

- Ap43 Access Point DatasheetDocument6 pagesAp43 Access Point DatasheetPaisarn UmpornjarassaengNo ratings yet

- (Guy - Exton) - Brexit and Game Theory A Single-Case AnalysisDocument9 pages(Guy - Exton) - Brexit and Game Theory A Single-Case AnalysisAmairani IbáñezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Cultural and Sociopolitical EvolutionDocument7 pagesLesson 2: Cultural and Sociopolitical EvolutionAmanda FlowerNo ratings yet

- Vol-IV Approved Vendor ListDocument29 pagesVol-IV Approved Vendor ListabhishekNo ratings yet

Constructing Markets and Organizing Boundaries 1

Constructing Markets and Organizing Boundaries 1

Uploaded by

Fatoumata GayeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Constructing Markets and Organizing Boundaries 1

Constructing Markets and Organizing Boundaries 1

Uploaded by

Fatoumata GayeCopyright:

Available Formats

CONSTRUCTING MARKETS AND ORGANIZING BOUNDARIES:

ENTREPRENEURIAL ACTION IN NASCENT FIELDS

FILIPE M. SANTOS

INSEAD

Boulevard de Constance

77302 Fontainebleau, France

E-mail: filipe.santos@insead.edu

KATHLEEN M. EISENHARDT

Stanford University

INTRODUCTION

How do managers define their firm’s scope of activities in nascent markets? The

organization and strategy literatures have focused primarily on the definition of organizational

boundaries in large, established firms operating in existing markets. Yet, nascent markets pose

different and perhaps more difficult challenges as compared to those faced by managers in

existing markets (Dougherty 1990; Aldrich and Baker 2001). We define nascent markets as new

fields of activity emerging outside the bounds of existing industries. They constitute high-

velocity settings characterized by frequent, often non-linear change (Eisenhardt and Bourgeois

1988), extreme ambiguity regarding industry structure, and lack of shared understandings from

which to create meaning (Aldrich and Fiol 1994). Therefore, the applicability of extant theories

on how executives make decisions regarding the scope of the firm is unclear. Consider TCE

(Williamson 1981): how can managers decide between contracting and internalizing an activity

in the absence of an industry value chain providing alternative governance arrangements?

Regarding resource dependence views, how can managers control key dependencies when

important players are not identified and their potential role in the nascent market is ambiguous

(Aldrich and Baker 2001)? Regarding competence views (Argyres 1996), how can managers

leverage resources into different markets when it is not clear which resources are valuable and

market segments are not yet defined (Brown and Eisenhardt 1998)?

These challenges in defining the firm’s scope in nascent markets are compounded for

entrepreneurial firms, who are often the pioneers that address these markets. In contrast to

established firms, entrepreneurial firms typically have an incipient set of activities (Aldrich and

Fiol 1994; Aldrich 1999). In this situation, the received wisdom on boundary decisions may not

apply. For example, minimizing costs may not be a central concern for entrepreneurs because

typically they do not have a well-defined and stable set of activities to perform. Simply surviving

may be more crucial since entrepreneurs usually start in a weak strategic position. Moreover,

entrepreneurs need to establish themselves in an initial market, but do not usually have a strong

resource base nor established competencies to leverage.

Yet, for a team of entrepreneurs creating a firm to address a nascent market, managing

boundaries may be critical in creating a context within which economic activity is organized and

sensemaking can occur (Aldrich 1999). Moreover, while founding a firm to address a nascent

market is, perhaps, the most “foolish” and failure prone entrepreneurial activity (Aldrich and Fiol

1994), it is also the one with the highest potential for creating value and transforming industries

(Schumpeter 1934; Drucker 1985). If wise choices regarding the scope of activities can improve

Academy of Management Best Conference Paper 2004 BPS: J1

the likelihood of success for these firms, then it is important to understand what processes are

used and how they are implemented. Specifically, the research question is: how do executives in

entrepreneurial firms addressing nascent markets organize the boundaries of their firms?

RESEARCH METHODS

Given the limited theory, and the goal of exploring organizational phenomena in a new

setting, an exploratory approach based on grounded theory building is suggested (Glaser and

Strauss 1967; Eisenhardt 1989). The research design is an inductive, multiple case, embedded

study. Multiple cases enable a replication logic in which the set of cases is treated as a series of

experiments, with each case serving to confirm or disconfirm the inferences drawn from the

others (Yin 1994). A multiple case study typically results in better-grounded and more general

theory than single cases (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Eisenhardt 1989).

The sample is composed of five firms founded to address different nascent markets. To

enhance the generalizability of the findings, the sample includes firms addressing nascent

markets in five different domains and reflects diverse founding situations (Harris and Sutton

1986). Given the goal of understanding how boundaries are managed, this is a descriptive study

requiring a longitudinal design. The sampling thus focuses on firms that were still in existence in

2001, the year that the study started. This allows studying the early drivers of boundary-setting

and the temporal dynamics of the process (Aldrich and Fiol 1994).

This study has two main data sources: archival and interviews (see table 1). The archival

data include both internal and external sources. The interviews were semi-structured and focused

on both internal and external informants. We conducted an average of nine interviews per case

for a total of 45 interviews, including the founder and/or senior executives for the five firms.

------------------------

Table 1 about here

-------------------------

RESULTS

The emergent theoretical framework suggests that entrepreneurs aim to attain a defensible

leadership position by reaching critical mass in a distinct market segment that the firm

constructs. To achieve this objective, entrepreneurs use three main processes:

First, entrepreneurs attempt to claim a distinct segment of the nascent market by

reshaping the pattern of meanings held by market actors. They do this by developing an identity

for both the firm and the market. The mechanisms used to develop an identity are the adoption of

templates, the provision of leadership signals, and the dissemination of stories. Entrepreneurs use

these mechanisms in an attempt to become the legitimate and leading player for the market,

making the firm a cognitive referent. Failing to achieve this, entrepreneurial firms risk becoming

a marginal player because either a distinct market does not emerge or it grows under the

direction of other players.

Second, entrepreneurs carve out clear boundaries by reshaping the structure of roles of

established players vis-a-vis their firm. This is done through the co-optation of powerful players,

using revenue sharing agreements, “anti-leader” positioning, and equity investments as

Academy of Management Best Conference Paper 2004 BPS: J2

mechanisms to obtain the support of these players. By structuring the roles in the market,

entrepreneurs are able to reduce the ambiguity they face and prevent competition in the market.

Failing to achieve this, entrepreneurs risk early competition from powerful players, which can

reduce the profitability of the nascent market or lead to the firm’s demise as a central player in a

distinct market segment.

Third, entrepreneurs attempt to dominate the space within the defined boundaries by

reshaping the ownership of resources. The rationale is to preserve the integrity of the market

against the efforts of other firms trying to construct their own markets or trying to assume control

of the market they are claiming. Entrepreneurs use acquisitions of smaller firms to increase their

market coverage, cancel possible entry points for more powerful competitors, and eliminate

threatening business models. Failing to sustain control of the market, entrepreneurial firms risk

losing market share and no longer being able to influence the direction of the market.

Fundamentally, this study suggests how entrepreneurs in nascent markets conceptualize

and try to achieve competitive advantage. Given the challenges that they face (i.e., high

ambiguity, low legitimacy, weak resource base, surrounded by powerful players), entrepreneurs

attempt to construct a distinct market that they can control using a combination of identity

mechanisms, alliances, and acquisitions (see table 2). The data suggest that entrepreneurs try to

establish boundaries in different arenas (i.e., cognitive, relational, ownership) in order to define a

new market and establish their leadership in it.

-------------------------

Table 2 about here

-------------------------

By managing boundaries over time in these different arenas, entrepreneurs achieve a

position and size that makes the firm’s viability independent of other market actors. This view on

competitive advantage suggests that efforts to reach critical mass will often dominate traditional

competitive drivers, such as governance cost, in making strategic decisions. It also suggests that

the survival of entrepreneurial firms as viable organizations seems inextricably linked to their

ability to control a growing market.

DISCUSSION

This research suggests that the boundaries of the firm and the boundaries of the market

are interwoven and often indistinguishable. Entrepreneurs do not necessarily select a particular

product/market domain for the firm (Chatterjee and Wernerfelt 1991) since markets are not

simply “out there” waiting to be chosen (Baum and Singh 1994) or even waiting to be discovered

by people with better access to localized information (Kirzner 1997). Entrepreneurs construct

new markets by structuring the nascent market around a perceived opportunity for the creation of

value. In a sense, the emergence of the segment as a viable market depends on the actions of

entrepreneurs (Rindova and Fombrun 2001). Thus, new markets are not inevitable outcomes of

technological advances or demographic changes, but fragile social constructions. They are willed

into existence by active entrepreneurs who operate in different arenas to define and maintain

boundaries over time. A central finding of this study is that nascent markets can be appropriately

interpreted as the outcome of creative entrepreneurial action.

Academy of Management Best Conference Paper 2004 BPS: J3

Second, this research contributes to resource dependence theory (Pfeffer and Salancik

1978) by showing that entrepreneurs may prefer the dependence that they can manage rather than

the ambiguity that they cannot control. Entrepreneurs pursue a strategy of reducing ambiguity

using co-optation alliances (Selznick 1949) to clarify their boundaries in relation to established

players in nearby markets. They do so even if they create dependence on these players. This

suggests a preference for pro-active structuring market relations to reduce ambiguity over a pure

strategy of dependence reduction.

Third, this research contributes to identity perspectives (Albert and Whetten 1985; Dutton

and Dukerich 1991). The evidence supports the usefulness of sensemaking processes driven by

identity in shaping organizational boundaries in ambiguous settings (Weick 1995; Sarasvathy

2001). This study also extends the identity literature by describing the mechanisms through

which identities are created. It suggests that claims to leadership (Rindova and Fombrun 2001)

need to be substantiated by high-profile and concrete actions of entrepreneurs.

Fourth, this study offers several implications for the strategy literature. One is suggesting

a use of alliances that goes beyond the access to new resources. Whereas recent literature see

alliances as an opportunity to access resources and competencies (Dyer and Singh 1998; Gulati

1998), the data show that entrepreneurs in nascent markets use co-optation alliances to clarify the

boundaries between their firm and powerful players. In addition, this study extends the social

capital literature related to alliances (Gulati 1995; Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1996) by

suggesting that “who you know” is not enough to attract partners. Entrepreneurs need to provide

concrete concessions to powerful players in order to co-opt them effectively, such as giving

partial ownership of the firm, sharing the revenues of the nascent market, or helping partners

compete against other powerful players. Finally, this study reveals a more varied use of

acquisitions that predicted by the literature. For example, some literature has focused on using

acquisitions to internalize new technology-based resources (Ahuja and Katila 2001). Although

the evidence supports the use of acquisitions to obtain new resources, it also suggests that many

acquisitions have a power rationale, involving either acquiring resources to prevent competitors

from getting them, or absorbing threatening firms to destroy them.

CONCLUSION

Fundamentally, this study suggests an expanded role for entrepreneurs. The focus of

attention in entrepreneurship research has typically been on garnering tangible resources to

develop new products for an identified market (Kirzner 1997; Gartner 1985). This study,

however, suggests that entrepreneurs do more than discover markets and recombine resources.

Entrepreneurs perceive new opportunities for the creation of value, and construct a market

around those opportunities. Constructing a market requires that entrepreneurs operate in different

arenas and set boundaries in each of them, using strategic mechanisms such as identity, alliances,

and acquisitions. Only by understanding what entrepreneurs do in these arenas and how they do

it, can we truly understand entrepreneurial action and the processes of creating viable firms.

REFERENCES

Ahuja, G. and R. Katila (2001). "Technological Acquisitions and the Innovation Performance of

Acquiring Firms." Strategic Management Journal 15(3): 103-120.

Albert, S. and D. Whetten (1985). Organizational Identity. Research in Organizational Behavior.

B. M. Staw. Greenwich, CT, JAI Press. 7: 263-295.

Academy of Management Best Conference Paper 2004 BPS: J4

Aldrich, H. E. (1999). Organizations Evolving. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications.

Aldrich, H. E. and T. Baker (2001). Learning and Legitimacy: Entrepreneurial Responses to

Constraints on the Emergence of New Populations and Organizations. The Entrepreneurship

Dynamic. C. B. Schoonhoven and E. Romanelli. Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press:

207-235.

Aldrich, H. E. and C. M. Fiol (1994). "Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry

creation." Academy of Management Review 19(4): 645-670.

Argyres, N. (1996). "Capabilities, Technological Diversification and Divisionalization." Strategic

Management Journal 17: 395-410.

Baum, J. A. and J. V. Singh (1994). "Organizational Niches and the Dynamics of Organizational

Founding." Organization Science 5(4): 483-501.

Brown, S. L. and K. Eisenhardt (1998). Competing on the Edge - Strategy as Structured Chaos.

Boston, MA, Harvard Business School Press.

Chatterjee, S. and B. Wernerfelt (1991). "The Link Between Resources and Type of

Diversification." Strategic Management Journal 12(1): 33-48.

Dougherty, D. (1990). "Understanding New Markets for New Products." Strategic Management

Journal 11(Summer Special Issue): 59-78.

Drucker, P. (1985). Innovation and Entrepreneurship. New York, Harper Business.

Dutton, J. E. and J. M. Dukerich (1991). "Keeping an Eye on the Mirror: Image and Identity in

Organizational Adaptation." Academy of Management Journal 34(3): 517-554.

Dyer, J. H. and H. Singh (1998). "The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of

interorganizational competitive advantage." Academy of Management Review 23(4): 660-

679.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). "Building Theories from Case Study Research." Academy of

Management Review 14: 532-550.

Eisenhardt, K. M. and L. J. Bourgeois, III (1988). "Politics of Strategic Decision Making in

High-Velocity Environments: Toward a Mid-range Theory." Academy of Management

Journal 31(4): 737-770.

Eisenhardt, K. M. and C. B. Schoonhoven (1996). "Resource-based view of strategic alliance

formation: Strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms." Organization Science 7(2):

136-150.

Glaser, B. and A. L. Strauss (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for

Qualitative Research. London, Wiedenfeld and Nicholson.

Gulati, R. (1995). "Social Structure and Alliance Formation Patterns: A Longitudinal Analysis."

Administrative Science Quarterly 40: 619-652.

Gulati, R. (1998). "Alliances and networks." Strategic Management Journal 19(4): 293-317.

Harris, S. and R. I. Sutton (1986). "Functions of Parting Ceremonies in Dying Organizations."

Academy of Management Journal 29(1): 5-30.

Kirzner, I. M. (1997). "Entrepreneurial Discovery and the Competitive Market Process: An

Austrian Approach." Journal of Economic Literature 35(1): 60-85.

Pfeffer, J. and G. Salancik (1978). The External Control of Organizations: A Resource

Dependence Perspective. New York, Harper & Row Publishers.

Rindova, V. P. and C. J. Fombrun (2001). Entrepreneurial Action in the Creation of the Specialty

Coffee Niche. The Entrepreneurship Dynamic. C. B. Schoonhoven and E. Romanelli.

Stanford, CA, Stanford University Press: 236-261.

Academy of Management Best Conference Paper 2004 BPS: J5

Sarasvathy, S. (2001). "Causation and Effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic

inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency." Academy of Management Review 26(2): 243-

288.

Schumpeter, J. (1934). The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA, Harvard

University Press.

Selznick, P. (1949). TVA and the Grass Roots. Berkeley, University of California Press.

Weick, K. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. London, Sage Publications.

Williamson, O. E. (1981). "The Economics of Organizations: The Transaction Cost Approach."

American Journal of Sociology 87(3): 548-577.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case Study Research - Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage

Publications.

TABLE 1: DESCRIPTION OF SAMPLE FIRMS AND CASE DATA

Pseudonym Harbor Secret Magic Midway Saturn

Domain Virtual Digital Online Enterprise Networking

Marketplace Services Commerce Software Hardware

Founding Stumbled into Technology Opportunity Opportunity Opportunity

Context market looking for looking for then acquire then build

market market technology technology

Archival Data

Audio/Video 4 4 5 4 6

Int. Sources 1700 pages 1600 pages 1800 pages 1400 pages 1300 pages

Ext. Sources 1100 pages 800 pages 1400 pages 1000 pages 1000 pages

Interviews 11 7 8 12 7

Note: All firms were founded in the period from late 1994 to end of 1995 in the U.S.

TABLE 2: FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGING BOUNDARIES

Framework Claiming a Demarcating the Controlling the

Elements Market Market Market

Goal Reshape patterns of Reshape structure Reshape ownership of

meaning of roles resources

Dominant Logic Sensemaking Co-optation Ownership

Process Shaping an identity Developing Making acquisitions

alliances

Mechanisms/ - Adopt templates - Equity - Increase market

Rationales - Disseminate investments coverage

stories - Revenue sharing - Eliminate

- Provide agreements competitive threats

leadership signals - Anti-leader - Block entry of

alliances powerful players

Desired Become cognitive Reduce level of Increase market share

Outcome referent competition

Academy of Management Best Conference Paper 2004 BPS: J6

You might also like

- Juran S Quality Planning andDocument1 pageJuran S Quality Planning andDebabrata Paul9% (11)

- Why Economics Has Been Fruitful For StrategyDocument5 pagesWhy Economics Has Been Fruitful For Strategypritesh1983No ratings yet

- Porter's Five Forces: Understand competitive forces and stay ahead of the competitionFrom EverandPorter's Five Forces: Understand competitive forces and stay ahead of the competitionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- Marketing Concept NPODocument26 pagesMarketing Concept NPOKristy LeNo ratings yet

- Ambidextrous Strategies and Innovation PDFDocument9 pagesAmbidextrous Strategies and Innovation PDFLeidy SánchezNo ratings yet

- Outside in & Inside OutDocument44 pagesOutside in & Inside OutSlobodan AdzicNo ratings yet

- The Market Driven Organization: Understanding, Attracting, and Keeping Valuable CustomersFrom EverandThe Market Driven Organization: Understanding, Attracting, and Keeping Valuable CustomersNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Spitting Out The HookDocument3 pagesModule 3 Spitting Out The Hookapi-538740413No ratings yet

- Stratagic PlanningDocument6 pagesStratagic Planningseeraju143No ratings yet

- Teece Dynamic CapabilitiesDocument35 pagesTeece Dynamic CapabilitiesDiana Carolina Aguilar OlarteNo ratings yet

- IOM Internet TopicsDocument5 pagesIOM Internet TopicsOwenevan EvanowenNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 CDMDocument40 pagesUnit 5 CDMManojkumar MohanasundramNo ratings yet

- 1994 - DAY - The Capabilities of Market-Driven OrganizationsDocument17 pages1994 - DAY - The Capabilities of Market-Driven OrganizationsClóvis Teixeira FilhoNo ratings yet

- 10 1109@itmc 2013 7352658Document14 pages10 1109@itmc 2013 7352658Wilson SCKUDLAREKNo ratings yet

- 波特5力pdfDocument15 pages波特5力pdfrdtrinyNo ratings yet

- McDonald-Market Segmentation EJMDocument26 pagesMcDonald-Market Segmentation EJMmabdulazeez01100% (1)

- Rex - Research Proposal SentDocument15 pagesRex - Research Proposal SentFakir TajulNo ratings yet

- Corporate DiversificationDocument16 pagesCorporate DiversificationCẩm Anh ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Managerial EconomicsDocument9 pagesManagerial EconomicsAbhishek ModakNo ratings yet

- RBV & Foundation For A Market Segmentation TheoryDocument5 pagesRBV & Foundation For A Market Segmentation TheoryZXZXNo ratings yet

- New Venture Strategies: Transforming Caterpillars Into Butter IesDocument38 pagesNew Venture Strategies: Transforming Caterpillars Into Butter Iesbabak_200028No ratings yet

- VERNON - Dialectic ReportDocument12 pagesVERNON - Dialectic ReportCleoNo ratings yet

- BCG MatrixDocument5 pagesBCG Matrixprab990050% (2)

- MS 29Document8 pagesMS 29Rajni KumariNo ratings yet

- Introduction 130407092142 Phpapp01Document69 pagesIntroduction 130407092142 Phpapp01Pari Savla100% (1)

- 9d6e PDFDocument48 pages9d6e PDFHarika KollatiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Transformation and The Success of High Technology Companies Edward B. Roberts Mit Sloan School of Management AUGUST 1989 WP # 3066-89 BPSDocument35 pagesStrategic Transformation and The Success of High Technology Companies Edward B. Roberts Mit Sloan School of Management AUGUST 1989 WP # 3066-89 BPSHa TranNo ratings yet

- MBA 113 - Reaction Paper 7Document6 pagesMBA 113 - Reaction Paper 7Denise Katrina PerezNo ratings yet

- JohnsonDocument11 pagesJohnsonMohd NajibNo ratings yet

- Resumen RumeltDocument5 pagesResumen RumeltselerovsNo ratings yet

- Market Segmentation LilienDocument32 pagesMarket Segmentation LilienJuanGreenmanNo ratings yet

- American Marketing Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of MarketingDocument10 pagesAmerican Marketing Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Journal of MarketingGall AnonimNo ratings yet

- Competitive Strategy of Private EquityDocument48 pagesCompetitive Strategy of Private Equityapritul3539No ratings yet

- On The Structural Dimension of Competitive StrategyDocument17 pagesOn The Structural Dimension of Competitive StrategyAus FirdausNo ratings yet

- Strategy and Performance - Asp PDFDocument5 pagesStrategy and Performance - Asp PDFJay Aubrey PinedaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityDocument38 pagesEvaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityrerereNo ratings yet

- Marketing Theory With Strategic Orientation PDFDocument12 pagesMarketing Theory With Strategic Orientation PDFNarmin Abida0% (1)

- Business Credit Solutions: Get A Credit Report Get A D&B D-U-N-S Number Monitor My Business Credit - FREE TRIAL!Document14 pagesBusiness Credit Solutions: Get A Credit Report Get A D&B D-U-N-S Number Monitor My Business Credit - FREE TRIAL!Harleen KaurNo ratings yet

- Structure & StrategyDocument4 pagesStructure & Strategyjacintavike42No ratings yet

- An IntraDocument16 pagesAn IntraUnachittranjan KumarNo ratings yet

- BB31403Document4 pagesBB31403nadiaNo ratings yet

- Thesis 234Document15 pagesThesis 234Villaflores HannaNo ratings yet

- Towards A Dynamic Theory of StrategyDocument23 pagesTowards A Dynamic Theory of StrategymirianalbertpiresNo ratings yet

- 316082Document28 pages316082Lim100% (1)

- M N V: T E E : Arketing in EW Entures Heory and Mpirical VidenceDocument38 pagesM N V: T E E : Arketing in EW Entures Heory and Mpirical Videncevk sarangdevotNo ratings yet

- 00 Day, George S. (1994) - The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58 (4), 37-52. Doi 10.1177:002224299405800404Document16 pages00 Day, George S. (1994) - The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58 (4), 37-52. Doi 10.1177:002224299405800404Andrés GómezNo ratings yet

- Herrigel. Autoparts-OEMcompetition PDFDocument35 pagesHerrigel. Autoparts-OEMcompetition PDFmateoNo ratings yet

- Miles and SnowDocument7 pagesMiles and SnowGLOBOPOINT CONSULTANTSNo ratings yet

- Table 2.1. The Evolution of Strategic ManagementDocument4 pagesTable 2.1. The Evolution of Strategic Managementanon_706827441No ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial StrategiesDocument4 pagesEntrepreneurial StrategiesNyegran LauraNo ratings yet

- Sociology, pp.82:929-964Document3 pagesSociology, pp.82:929-964Nikelas TanNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Competencies For Leveraging Core Products in Global MarketsDocument14 pagesKnowledge Competencies For Leveraging Core Products in Global MarketsprandourmiNo ratings yet

- BCG and GE McKinsey Matrix QDocument12 pagesBCG and GE McKinsey Matrix QRian WallaceNo ratings yet

- EnvironmentsDocument4 pagesEnvironmentsjonas887No ratings yet

- Strategic Assets and Organizational RentDocument14 pagesStrategic Assets and Organizational RentEduardo SantocchiNo ratings yet

- Armour and TeeceDocument18 pagesArmour and Teecea20236878No ratings yet

- Revisiting Marketing's Lawlike Generalizations: Jagdish N. ShethDocument17 pagesRevisiting Marketing's Lawlike Generalizations: Jagdish N. ShethsaifulyusoffusmNo ratings yet

- StrategyDocument10 pagesStrategyAmit MishraNo ratings yet

- A Strategic Process Guide: Article Relevant To Professional 1 Management & Strategy Author: Fergus McdermottDocument4 pagesA Strategic Process Guide: Article Relevant To Professional 1 Management & Strategy Author: Fergus McdermottGodfrey MakurumureNo ratings yet

- EBS-Mba 4Document25 pagesEBS-Mba 4Mainpal YadavNo ratings yet

- Full Text 01Document40 pagesFull Text 01Kamran AliNo ratings yet

- FBM Assessment 4Document13 pagesFBM Assessment 4Benjamin DanielsNo ratings yet

- Galateanu 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.%3A Mater. Sci. Eng. 400 062009Document9 pagesGalateanu 2018 IOP Conf. Ser.%3A Mater. Sci. Eng. 400 062009Fatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- Consequences ETFDocument17 pagesConsequences ETFFatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- Constructing and Using Nascent Market LabelsDocument56 pagesConstructing and Using Nascent Market LabelsFatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- 2014ValueofValueMarketing TheoryDocument5 pages2014ValueofValueMarketing TheoryFatoumata GayeNo ratings yet

- F520Document2 pagesF520Marcos AldrovandiNo ratings yet

- Chafi2009Document7 pagesChafi2009radhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Design of Gear BoxDocument19 pagesDesign of Gear BoxSUMIT MALUSARE100% (1)

- St. Andrew Academy Bacarra, Ilocos Norte First Grading-Grade 7 MathematicsDocument10 pagesSt. Andrew Academy Bacarra, Ilocos Norte First Grading-Grade 7 MathematicsJACOBAGONOYNo ratings yet

- Billet D Humeur 7 Reasons Why The LeidenDocument5 pagesBillet D Humeur 7 Reasons Why The LeidenjohnkalespiNo ratings yet

- 2.7 2012 Influence of Implant Neck Design and Implant-Abutment Connection Type On Peri-Implant Health. Radiological StudyDocument9 pages2.7 2012 Influence of Implant Neck Design and Implant-Abutment Connection Type On Peri-Implant Health. Radiological StudyDuilioJrNo ratings yet

- DDBMS ArchitectureDocument62 pagesDDBMS ArchitectureFranklin DorobaNo ratings yet

- Corrosión Manual NalcoDocument126 pagesCorrosión Manual NalcotinovelazquezNo ratings yet

- Zenner DiodeDocument23 pagesZenner DiodeKrishanu NaskarNo ratings yet

- Decision Trees - 2022Document49 pagesDecision Trees - 2022Soubhav ChamanNo ratings yet

- Malhotra, Garg, and Rai - Analysing The NDHM Health Data Management PolicyDocument30 pagesMalhotra, Garg, and Rai - Analysing The NDHM Health Data Management Policysimran sabharwalNo ratings yet

- TIP35/35A/35B/35C: Silicon NPN Power TransistorsDocument4 pagesTIP35/35A/35B/35C: Silicon NPN Power TransistorsJose David Perez ParadaNo ratings yet

- A Review of RhomboidityDocument10 pagesA Review of RhomboidityShrey GulatiNo ratings yet

- Astm C 1173Document4 pagesAstm C 1173Andrea Bernal JaraNo ratings yet

- Gen4 Product Manual V3.0Document118 pagesGen4 Product Manual V3.0velmusNo ratings yet

- Childhood and Growing UpDocument181 pagesChildhood and Growing UpManichander100% (2)

- 4robbins Mgmt15 PPT 02-Updated3Document46 pages4robbins Mgmt15 PPT 02-Updated3SanaaAbdelganyNo ratings yet

- AnalysisofUnder reamedPilesSubjectedtoDifferentTypesofLoadinClayeySoil 1 8 PDFDocument9 pagesAnalysisofUnder reamedPilesSubjectedtoDifferentTypesofLoadinClayeySoil 1 8 PDFAkhilesh Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Eurasian PlateDocument6 pagesEurasian PlateJoshua SalazarNo ratings yet

- Motivation: Self-Efficacy Has A Positive Impact On PerformanceDocument3 pagesMotivation: Self-Efficacy Has A Positive Impact On PerformanceVishavjeetDevganNo ratings yet

- 1SDA067399R1 xt1c 160 TMD 160 1600 3p F FDocument4 pages1SDA067399R1 xt1c 160 TMD 160 1600 3p F FBianca OlaruNo ratings yet

- Better Graphics r10 PDFDocument45 pagesBetter Graphics r10 PDFdocsmsNo ratings yet

- Purdue Engineering 2010 PDFDocument98 pagesPurdue Engineering 2010 PDFGanesh BabuNo ratings yet

- Employment News 30 September - 06 OctoberDocument39 pagesEmployment News 30 September - 06 OctoberNishant Pratap Singh100% (1)

- Ap43 Access Point DatasheetDocument6 pagesAp43 Access Point DatasheetPaisarn UmpornjarassaengNo ratings yet

- (Guy - Exton) - Brexit and Game Theory A Single-Case AnalysisDocument9 pages(Guy - Exton) - Brexit and Game Theory A Single-Case AnalysisAmairani IbáñezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2: Cultural and Sociopolitical EvolutionDocument7 pagesLesson 2: Cultural and Sociopolitical EvolutionAmanda FlowerNo ratings yet

- Vol-IV Approved Vendor ListDocument29 pagesVol-IV Approved Vendor ListabhishekNo ratings yet