Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reality - The Ultimate Question

Reality - The Ultimate Question

Uploaded by

David A. HernandezOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reality - The Ultimate Question

Reality - The Ultimate Question

Uploaded by

David A. HernandezCopyright:

Available Formats

Hernandez 1 Reality: The Ultimate Question Along the course of human civilization developments have been made through

the systematic approach of solving problems by applying logic and reason. One of the ultimate questions of humanity is the one that demands an answer to define a concept of reality. In Greece, Pythagoras, a philosopher who made a huge contribution to human history attempted to answer such question by addressing mathematics to define it. Aristotle, another Greek intellectual, made huge efforts to define it through the concept of the ultimate good or toward which, in the final analysis, all human actions ultimately aim (Hughes 2). The quest to define the cosmos with its laws and implicit concepts was one of the main concerns for Aristotle and Pythagoras, such quest brought a level of thinking that translated in the development of concepts such as the Pythagorean reality and the Aristotelian metaphysics. According to the Oxford Dictionary, reality is defined as the state of things as they actually exist, rather than as they may appear or might be imagined, it includes everything that is and has been, whether or not it is observable or comprehensible, it is everything that has existed, exists, or will exist, not just in the mind, or even more broadly also including what is only in the mind. However, Aristotle would probably agree only partially with such definition since the concept of eudaimonia, which can also be translated as blessedness or living well, and which is not a static state of being but a type of activity, should be addressed to fully define reality through a both physical and metaphysical approach. Pythagoras would probably agree with some of the ideas exposed, nevertheless the lack of mentioning explicitly the mathematical world and its laws would represent a barrier to fully agree with the concept. Though Pythagoras' concept of structure is ideal, all structure, even perfect structure, creates limits. What makes up a structure is a set of rules, definitions, or dimensions that create

Hernandez 2 the basis for the structure (Nies 2). The existence of these standards implies that there is also that which is not structured, and from which structure must be created. Pythagoras recognized the fact that structure cannot be defined without defining non-structure as well. He also understood structure and non-structure to be at odds with each other, each trying to take over the other (Nies 2). To explain the relative stability of reality, Pythagoras envisioned a reconciling factor that limits the movement of structure into non structure and vise-versa, thus it is the third factor that completes Pythagoras' triadic cosmological archetype (Nies 3). Though Pythagorean triadic themes can be found throughout classical culture, classical civilization does not represent these themes in the abstract way in which Pythagoreans do, but, instead, personifies these concepts copiously throughout mythology (Nies 5). Another mythological representation of the Pythagorean triad is the ocean, personified as the god Oceanus (Okeanos) or simply Ocean (Nies 5). The Greeks and Romans believe that their universe was divided into two major parts: the realm of the living and another realm that only the gods or the dead could enter. What separates these two worlds is Oceanus. At this point in time, the ocean was not perceived as crossable, and so provided a perfect third element, a barrier between the two realms (Nies 7). Though our "civilized minds" no longer prohibit the consumption beans or shun contact with a pregnant woman, some of us still accept the tripartite representation of a single God. Furthermore, we commonly understand our reality in terms of space and time, though we leave the mathematical representation to the scientists. It is ironic that we remember Pythagoras only for the simple equation of right triangle while his idea to mathematically represent reality is one that remains central to modern life (Nies 10).

Hernandez 3 Works Cited Bishop, Philip E. Ancient Civilizations. Adventures in the Human Spirit. Sixth Edition. Kara Hattersley-Smith. London: Prentice Hall, 2009. Print. Ballew, Lynne. Straight and Circular: A Study of Imagery in Greek Philosophy. Assen, Netherlands: Van Gorcum, 1979. Colavito, Maria Maddalena. The Pythagorean Intertext in Ovid's Metamorphosis. Queenston, Canada: Edwin Mellen Press, 1989. Dante. The Divine Comedv. Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. The Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces. 7th ed. V. 1. Eds. Sarah Lawall and Maynard Mack. New York: Norton & Company, 1999. Ferrante, Joan. "A Poetics of chaos and harmony" in The Cambridge Companion to Dante. Ed. Rachel Jacoff. Cambridge: UP, 1998. Freccero, John. Dante: The Poetics of Conversion. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986. Guthrie, Kenneth Sylvan. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library. Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press, 1987. Guthrie, W.Ke. A History of Greek Philosophy. Cambridge: University Press, 1962. Hesiod. The Poems of Hesiod. Trans. R. M. Frazer. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1983. Niess, Leah, "The Structure of Pythagorean Reality" (2000). Honors Theses. Paper 94. Web. Rose, H. J. Ancient Greek Religion. London: Gainsborough Press, 1948.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Marksheet ITI 2st YEARDocument1 pageMarksheet ITI 2st YEARRaiesh Alam100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Mastery of Active Listening SkillsDocument5 pagesMastery of Active Listening SkillsLai RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Plant LessonDocument3 pagesPlant Lessonapi-259470709No ratings yet

- The Psychosocial Dynamics ofDocument21 pagesThe Psychosocial Dynamics ofCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Priority RD Research Agenda 2017 2022Document39 pagesPriority RD Research Agenda 2017 2022Ferlene PalenciaNo ratings yet

- Formulating Your Philosophy of EducationDocument10 pagesFormulating Your Philosophy of EducationRichelle CuetoNo ratings yet

- Project: Review of A Movie "Freedom Writers": Major CharactersDocument2 pagesProject: Review of A Movie "Freedom Writers": Major CharactersZargham AliNo ratings yet

- Responding To Revise and ResubmitDocument4 pagesResponding To Revise and ResubmitMicky AmekanNo ratings yet

- Child Protection Policy INSETDocument23 pagesChild Protection Policy INSETnymphaNo ratings yet

- PingBills - Senate Bill 259: Philippine Air Force AcademyDocument5 pagesPingBills - Senate Bill 259: Philippine Air Force AcademySenator Ping Lacson Media TeamNo ratings yet

- HW Collage & Essay (Compatibility Mode)Document3 pagesHW Collage & Essay (Compatibility Mode)Alexander Joseph Lao IlaganNo ratings yet

- SAP SLCM Academic Structure CookbookDocument60 pagesSAP SLCM Academic Structure Cookbookp13t3rNo ratings yet

- LESSON 11 Strategy 3 Inductive Guided InquiryDocument12 pagesLESSON 11 Strategy 3 Inductive Guided InquiryDaryll QuilantangNo ratings yet

- Reading Experience of Senior High School Students in Utilizing Audio-Aided MaterialsDocument9 pagesReading Experience of Senior High School Students in Utilizing Audio-Aided MaterialsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- P.E 10 SDLP Mar 27 HiphopDocument6 pagesP.E 10 SDLP Mar 27 HiphopNunag Romel P.No ratings yet

- Audit of Texas Education Agency Selected ContractsDocument51 pagesAudit of Texas Education Agency Selected ContractsMede NixNo ratings yet

- DLL - Mathematics 3 - Q3 - W2Document3 pagesDLL - Mathematics 3 - Q3 - W2shuckss taloNo ratings yet

- Bar TipsDocument3 pagesBar TipsBernice Joana L. Piñol100% (1)

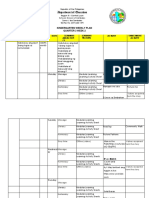

- Department of Education: Kindergarten Weekly Plan Quarter 3 Week 2Document3 pagesDepartment of Education: Kindergarten Weekly Plan Quarter 3 Week 2jemima mae isidroNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan English Year 3Document28 pagesLesson Plan English Year 3Annisa Ulhusna100% (1)

- m4 Act3 Inclusive Classroom ManagementDocument3 pagesm4 Act3 Inclusive Classroom Managementapi-516574894No ratings yet

- Survey Questionnaire: Statement Always Sometimes Often NeverDocument4 pagesSurvey Questionnaire: Statement Always Sometimes Often NeverZarahJoyceSegoviaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 18-Table of SpecificationsDocument3 pagesLesson 18-Table of SpecificationsJohn Rey DumaguinNo ratings yet

- Davis Joint Unified School District Homework PolicyDocument7 pagesDavis Joint Unified School District Homework Policyafetnjvog100% (1)

- Improving Reading AchievementDocument111 pagesImproving Reading AchievementZyra Rose Leachon - YamsuanNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Navy: Submit This Form During Preliminary InterviewDocument3 pagesBangladesh Navy: Submit This Form During Preliminary InterviewSaikat ComputersNo ratings yet

- PrefaceDocument3 pagesPrefaceNahidul Islam IU0% (1)

- Marilyn Ferguson - The Aquarian Conspiracy, 1981, OCRDocument371 pagesMarilyn Ferguson - The Aquarian Conspiracy, 1981, OCRMLNo ratings yet

- Southwood School Case StudyDocument14 pagesSouthwood School Case StudyRia Zita GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Commedia Resource Pack - 2016Document19 pagesCommedia Resource Pack - 2016Trev Neo100% (1)