Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unit 1 Karakoram Range

Unit 1 Karakoram Range

Uploaded by

Adnan Hussain Gakhar - 55163/TCHR/BLGTC0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views6 pagesgood

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentgood

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views6 pagesUnit 1 Karakoram Range

Unit 1 Karakoram Range

Uploaded by

Adnan Hussain Gakhar - 55163/TCHR/BLGTCgood

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 6

Karakoram Range

mountains, Asia

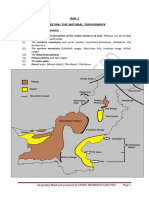

Hindu Kush and Karakoram Range

Karakoram Range, great mountain system extending some 300 miles (500 km) from the

easternmost extension of Afghanistan in a southeasterly direction along the watershed

between Central and South Asia. Found there are the greatest concentration of high

mountains in the world and the longest glaciers outside the high latitudes. The Karakorams

are part of a complex of mountain ranges at the centre of Asia, including the Hindu Kush to

the west, the Pamirs to the northwest, the Kunlun Mountains to the northeast, and

the Himalayas to the southeast. The borders of Tajikistan, China, Pakistan, Afghanistan,

and India all converge within the Karakoram system, giving this remote region great

geopolitical significance. The name “Kurra-koorrum,” a rendering of the Turkic term for

“Black Rock” or “Black Mountain,” appeared in early 19th-century English writings.

Physical features

Physiography

Karakoram Range: K2 (Mount Godwin Austen)

K2 (Mount Godwin Austen), in the Karakoram Range, viewed from the Gilgit-Baltistan

district of the Pakistani-administered portion of the Kashmir region.(more)

The Karakorams consist of a group of parallel ranges with several spurs. Only the central part

is a monolithic range. The width of the system is about 150 miles (240 km); the length is

increased from 300 miles (500 km) to 500 miles (800 km) if its easternmost extension—

the Chang Chenmo (Chinese: Qiangchenmo) and Pangong ranges of the Plateau of Tibet—is

included. The system occupies about 80,000 square miles (207,000 square km). The average

elevation of mountains in the Karakorams is about 20,000 feet (6,100 metres), and four peaks

exceed 26,000 feet (7,900 metres); the highest, K2 (Mount Godwin Austen), at 28,251 feet

(8,611 metres), is the second highest peak in the world.

The topography is characterized by craggy peaks and steep slopes. The southern slopes are

long and steep, the northern slopes steep and short. Cliffs and taluses (great accumulations of

large fallen rocks) occupy a vast area. In the intermontane valleys, rocky inclines occur

widely. Transverse valleys usually have the appearance of narrow, deep, steep ravines.

Glaciation and drainage

Because of their great height, the Karakorams exhibit heavy glaciation, particularly on the

southern, more humid slopes. Glaciers of the central, highest mountains include Hispar,

Chogo Lungma, Braldu, Biafo, Baltoro with its famous Concordia junction,

and Siachen (which is some 45 miles [70 km] long). The snow line on the southern slopes of

the Karakorams lies at an elevation of 15,400 feet (4,700 metres); glaciers extend down to

9,500 feet (2,900 metres). On the northern slopes the corresponding elevations are 19,400

feet (5,900 metres) and 11,600 feet (3,500 metres), respectively. Often, glaciers combine to

form complex glacial systems occupying not just valleys but entire watersheds. Seasonal

thawing of the glaciers gives rise to serious floods on the southern slopes. Traces of ancient

glaciation are evident at elevations as low as 8,500 feet (2,600 metres) and 2,800 feet (850

metres) in the Indus River valley.

The Karakorams serve as a watershed for the basins of the Indus and Yarkand rivers. The

formation of river channels, for the most part, occurs in the high-elevation zone, where the

melted waters of seasonal and perpetual snows and glaciers feed the rivers. Suspended

pulverized stone, or rock flour, makes glacial meltwater opaque. Rock flour and eroded

material from the mountain channels give the Indus the highest suspended sediment load of

any major river. Groundwater accumulates in the rocky talus and contributes to the flow

throughout the year.

Geology

Structurally, the Karakorams originated from folding in the Cenozoic Era (i.e., during the past

65 million years). Granites, gneisses, crystallized schists, and phyllites dominate the

geologic composition. To the south and north, the central rock core of the Karakorams is

edged by a region of limestones and micaceous slates of the Paleozoic and (partly) Mesozoic

eras (i.e., about 245 to 540 million years old). To the south the sedimentary rock is sometimes

cut by intrusions of granite. The surfaces of certain areas expose slate, which yields more

rapidly to weathering.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.Subscribe Now

At the end of the Mesozoic, the region of the Karakorams was characterized by great

structural changes, and the Karakorams emerged as the result of intensive geologically recent

upheavals. There is still frequent seismic activity in the region; some events are of great

violence and often trigger massive rock and ice avalanches. Hot springs are found in several

areas.

Climate

The climate of the Karakoram Range is for the most part semiarid and strongly continental.

The southern slopes are exposed to the moist monsoon (rain-bearing) winds coming in from

the Indian Ocean, but the northern slopes are extremely dry. On the lower and middle slopes,

rain and snow fall in small quantities; average annual precipitation does not exceed 4 inches

(100 mm). At elevations above 16,000 feet (4,900 metres), precipitation always takes a solid

form, but snow in June is not infrequent even at lower elevations. At elevations of about

18,700 feet (5,700 metres), the average temperature during the warmest month is lower than

32 °F (0 °C), and, at heights of between 12,800 and 18,700 feet (3,900 and 5,700 metres), the

temperature is lower than 50 °F (10 °C). Rarefied air, intensive solar radiation, strong winds,

and great diurnal ranges of temperature are characteristic climatic features of the region. The

extreme conditions in high-elevation snowfields cause Büsserschnee (German: “snow

penitents”), the formation of ablated snow hummocks three feet (one metre) or more tall.

Anabatic (upward-moving) winds produce extensive eolian erosion.

Plant and animal life

In the lower valleys almost, all profuse vegetation is anthropogenic (i.e., affected by human

activities). Mountain oases perched on rocky outcrops are watered by intricate irrigation

channels from melting glaciers. The arid and rocky lower slopes support only discontinuous

grazing areas, but extensive undulating pastures intersperse the high peaks. The Karakorams

have upper and lower tree lines, the upper delimited by cold and the lower by aridity; within

these lines is found only degraded, sparse tree cover. Willow, poplar, and oleander thickets

occur along watercourses up to 10,000 feet (3,000 metres). Juniper is found on high slopes

among seasonal snowfields. Shrubs of the genus Artemisia provide sparse cover on the lower

slopes.

Hunting by the local populace, and especially by military troops stationed on the frontiers,

has taken a severe toll on mountain wildlife. Marco Polo sheep, or argali, now breed only in

the eastern Pamirs and migrate to the western Karakorams. Ladakh urials (wild sheep) inhabit

the high, flatter mountains to the east, while Siberian ibex and markhors (both wild goats)

negotiate the craggy slopes. Brown bears, lynx, and snow leopards are endangered species.

The Khunjerab National Park in Pakistan and the contiguous Taxkorgan (Tash Kurghan)

Nature Reserve in China serve as refuges for high-mountain animals. In the eastern

margins, kiangs and several other wild ungulates, including a small number of wild yaks,

roam the desolate plateau. Large raptors, notably Himalayan griffons, lammergeiers, and

golden eagles, soar on the updrafts of mountain winds.

People of the Karakoram Range

Gilgit

Gilgit, Pakistani-administered sector of the Kashmir region.

Leh, India: palace of the kings of Ladakh

Palace of the kings of Ladakh (centre background) in Leh, Ladakh union territory, India.

(more)

The population of the Karakoram Range is concentrated in three towns in the

disputed Kashmir region of the northern Indian subcontinent—Gilgit and Skardu in Gilgit-

Baltistan (in the Pakistani-administered portion) and Leh in Ladakh union territory (in the

Indian-administered portion)—and in small villages throughout the region perched on rocky

slopes or beside raging torrents. Most mountain dwellers are Shiʿi Muslims of

the Ismāʿīli or Twelver (Ithnā ʿAshariyyah) sects. Tibetan Buddhism is prevalent in Ladakh.

Mountain Tajik, who speak Wakhī (an Iranian language), are interspersed with Turkic-

speaking Kyrgyz and Uighurs on the northern slopes, while on the southern slopes military

troops from lowland India and Pakistan intermingle with Kohistani- (Dardic-) speaking

people in the Gilgit district and with the Tibetan-speaking population of Baltistan and

Ladakh. On the northern, much drier Karakoram slopes descending to the oases around

the Tarim Basin in China, population density is quite low. An enclave of Burushaski-speaking

people exists in Hunza and Nagir and in the adjacent valley of Yasin. Their language is not

known to be related to any other.

Despite the marginality and remoteness of the Karakoram Range, the local population has

undergone considerable movement throughout its history. Raiding by caravans crossing the

range and a slave trade sustained by continual warfare caused wide dispersals. Passes for foot

traffic across the mountains, no longer used, led northward from Skardu and Leh and from

the Vale of Kashmir into western China (Xinjiang) via Taxkorgan (Tash Kurghan) and the

ancient trading centres of Yarkand (Shache) and Kashgar (Kashi) and the Tarim Basin oases.

Buddhist monasteries formerly exercised great control over subjects and land in the eastern

valleys.

Economy

Gilgit-Baltistan: Hunza River valley

Terraced fields in the Hunza River valley, Karakoram Range, Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistani-

administered Kashmir.(more)

Subsistence agriculture and livestock raising dominate the local economy. Crops are limited

to wheat, barley, sweet and bitter buckwheat, corn (maize), potatoes, and pulses. Tree crops,

especially apricots and walnuts, were once an important local food source. On the lower

slopes up to 7,000 feet (2,100 metres), the growing season is sufficient for double-cropping.

At these elevations the days are warm, the nights cool, and the air clear and clean; the aridity

of the region, however, precludes cultivation without the intricate irrigation facilities that are

a feature of all inhabited areas.

Continual periodic and permanent migration, reliance on central government subsidies, high

infant mortality, and chronic malnutrition are symptoms of the difficulty humans have had

adapting to this marginal environment. Service in military garrisons provides supplemental

income, as do remittances from migrants working elsewhere in India or Pakistan or in

the Persian Gulf states.

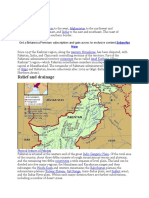

Three transmontane roads serve the southern slopes of the Karakoram Range—one from the

Kullu Valley in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh over several high passes to Leh, another

from the Vale of Kashmir also to Leh, and the hard-surfaced Karakoram Highway (completed

1978) following the Indus River gorge from Islamabad to Gilgit and proceeding on to

Kashgar. A frontier road from Lhasa, in the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, to Kashgar

skirts the eastern and northern margins of the Karakorams in China. There are daily

commercial flights to Leh from the Indian cities of Delhi and Chandigarh and to Skardu and

Gilgit from Islamabad, Pak.

Study and exploration

Both ancient Chinese documents, interpreted in the 19th century by the German

explorer Alexander von Humboldt, and medieval Arabic works record the pre-European

knowledge of Karakoram geography. Baltistan and its principal town, Skardu, appear on a

European map produced in 1680. Early 19th-century European travelers such as the

Englishmen William Moorcroft, George Trebeck, and Godfrey Thomas Vigne plotted the

locations of major rivers, glaciers, and mountains. The extraordinary topography, along with

protracted military tensions in the Karakorams between Russia and Britain and more recently

between China, Pakistan, and India, prompted many expeditions in the 19th and 20th

centuries. Most English exploration reflected military and political rather than scientific

considerations. Three brothers of the German Schlagintweit family pioneered the study of

glaciers as indicators of global climate change, techniques of climate measurement, and the

representation of mountain terrain on maps.

Other major scientific contributions were made by the Briton Martin Conway and by the

seven expeditions led by the Americans Fanny and William Workman in the early 20th

century. Later geomorphologic studies include those conducted by Italians, notably Ardito

Desio and Giotto Dainelli. Sustained study in the Karakorams in the late 20th and early 21st

centuries was undertaken primarily by Canadian, British, and American researchers, the work

of Kenneth Hewitt, John Shroder, and Lewis Owen being prominent. As a consequence of

this foreign interest and of India’s territorial disputes with both Pakistan and China, the

Karakorams are exceedingly well mapped. In addition, several dozen mountaineering

expeditions visit the area annually.

You might also like

- Mountain Ranges of PakistanDocument10 pagesMountain Ranges of PakistanSaid Qasim100% (1)

- The Deluged Civilization of The Caucasus Isthmus - Richard FessendenDocument158 pagesThe Deluged Civilization of The Caucasus Isthmus - Richard FessendenGeorges E. Kalfat67% (3)

- Unit 1 Topography of PakistanDocument13 pagesUnit 1 Topography of PakistanHaasan AttaNo ratings yet

- Full Geography NotesDocument118 pagesFull Geography NotesMuhammad Musa HaiderNo ratings yet

- CombinepdfDocument23 pagesCombinepdfshaheer chNo ratings yet

- Sir Usman Ahmed Geo NotesDocument122 pagesSir Usman Ahmed Geo NotesUzair siddiqui100% (2)

- The Natural Topography of PakistanDocument5 pagesThe Natural Topography of PakistanUmna AtharNo ratings yet

- Geography in Short ..Document69 pagesGeography in Short ..Umer Hameed88% (25)

- Physigrophy 0f PakistanDocument17 pagesPhysigrophy 0f PakistanMatira KhanNo ratings yet

- Jammu Kashmir PeopleDocument4 pagesJammu Kashmir PeopleMadhuNo ratings yet

- 4655 1Document10 pages4655 1Mian UmerNo ratings yet

- Hindu Kush: The and The Western MountainsDocument3 pagesHindu Kush: The and The Western Mountainsnzgzxg mZMgfNo ratings yet

- HimalayDocument6 pagesHimalaybaburaogtrwNo ratings yet

- Topograhpy Handout - HighlandsDocument62 pagesTopograhpy Handout - HighlandsABDUL HADINo ratings yet

- In Case U R V V FuckedDocument45 pagesIn Case U R V V Fuckeddaniyal ahmedNo ratings yet

- Jammu - Kashmir and LadakhDocument24 pagesJammu - Kashmir and LadakhDev MahaourNo ratings yet

- Ecology: Ālaya (Dwelling)Document5 pagesEcology: Ālaya (Dwelling)Tennety MrutyumjayaNo ratings yet

- CH 01 The Land of Pakistan-1Document52 pagesCH 01 The Land of Pakistan-1M.AazanQ DastiNo ratings yet

- Course: Geography of Pakistan, Part-I (4655) Semester: Spring, 2022 Level: MSCDocument12 pagesCourse: Geography of Pakistan, Part-I (4655) Semester: Spring, 2022 Level: MSCAmir AfridiNo ratings yet

- TopographyDocument14 pagesTopographydemira lalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Pak GeogDocument90 pagesChapter 2 Pak GeogAwais BakshyNo ratings yet

- Physical Regions of Jammu and KashmirDocument15 pagesPhysical Regions of Jammu and Kashmirginga716100% (1)

- GeographyDocument27 pagesGeographyAdnan Hussain Gakhar - 55163/TCHR/BLGTCNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-Natural TopographyDocument19 pagesChapter 1-Natural TopographyNawal FatimaNo ratings yet

- Ālaya (Dwelling), Literally, "Abode of The Snow"Document7 pagesĀlaya (Dwelling), Literally, "Abode of The Snow"aditya2053No ratings yet

- Iran Afghanistan China India Arabian Sea: Subscribe NowDocument3 pagesIran Afghanistan China India Arabian Sea: Subscribe Nownzgzxg mZMgfNo ratings yet

- Geography of JandkDocument6 pagesGeography of JandkSau RovNo ratings yet

- Topography Ch. 1Document17 pagesTopography Ch. 1Home Economics EducationNo ratings yet

- Swiss Tectonic ArenaDocument6 pagesSwiss Tectonic ArenashragrathNo ratings yet

- Geology of Salt RangeDocument18 pagesGeology of Salt RangeAdil KhanNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On Melting of IceDocument7 pagesA Case Study On Melting of IceRishav Dev PaudelNo ratings yet

- Geo 1Document2 pagesGeo 1Maaz MustafaNo ratings yet

- Land and Geography of KyrgyzstanDocument28 pagesLand and Geography of KyrgyzstanMark Joseph GamaoNo ratings yet

- Presentation About The Nature of TurkmenistanDocument9 pagesPresentation About The Nature of TurkmenistanSuray HudaynazarowaNo ratings yet

- 2 Land and People of PakistanDocument43 pages2 Land and People of PakistanYusra Khan100% (1)

- Asia and EuropeDocument5 pagesAsia and EuropeKirby AboNo ratings yet

- Geographical Profile of PakistanDocument5 pagesGeographical Profile of PakistanwaterbottleNo ratings yet

- Natural Topography of PakistanDocument25 pagesNatural Topography of Pakistansatayish100% (1)

- 634713719452792870Document59 pages634713719452792870Hurriyah KhanNo ratings yet

- Geography PPPDocument161 pagesGeography PPPMUHAMAD HUSSAINjunaidNo ratings yet

- Geography of PakistanDocument2 pagesGeography of PakistanajaxNo ratings yet

- Highland - WikipediaDocument3 pagesHighland - WikipediaMGR001No ratings yet

- Usama Naveed Topography of PakistanDocument13 pagesUsama Naveed Topography of PakistanNicki GNo ratings yet

- Blue Photo Sales PresentationDocument11 pagesBlue Photo Sales PresentationShradha JainNo ratings yet

- Siwaliks and Oild Bearing Tertiary DepositsDocument35 pagesSiwaliks and Oild Bearing Tertiary Depositsvenkatakrishna chalapaathi100% (5)

- Post 1857Document43 pagesPost 1857Asim HussainNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 and 2 (Topography and Climate)Document95 pagesTopic 1 and 2 (Topography and Climate)usmanrandhawa67889No ratings yet

- Zoological Bulletin VolDocument116 pagesZoological Bulletin VolEmm JaiNo ratings yet

- 1.1physical Features of PakistanDocument35 pages1.1physical Features of PakistanaNo ratings yet

- The Physiographic Features of IndiaDocument64 pagesThe Physiographic Features of IndiaJnanam100% (1)

- The Land of PakistanDocument54 pagesThe Land of Pakistanmina shamsNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument8 pagesDocumentAmna QayoumNo ratings yet

- Doodhgnaga 2Document8 pagesDoodhgnaga 2Pragya SourabhNo ratings yet

- Terrifc Terrains & Terrible Travels - V0.7Document237 pagesTerrifc Terrains & Terrible Travels - V0.7Elías VillalónNo ratings yet

- Shaikh Muhammad Saim Unzila Siddique Imran Hyder Channa Sarwat ZehraDocument56 pagesShaikh Muhammad Saim Unzila Siddique Imran Hyder Channa Sarwat ZehraAnonymous Eq8yA3Kd25No ratings yet

- IDocument5 pagesIanshum11No ratings yet

- TopographyDocument6 pagesTopographyRevolt 2.0No ratings yet

- Mountain Ranges of ScotlandDocument27 pagesMountain Ranges of ScotlandDavid BĂLȚĂȚEANUNo ratings yet

- Ladakh Guide & MapsDocument105 pagesLadakh Guide & MapstdudkowskiNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Ebook PDF Elemental Geosystems 7th Edition PDF ScribdDocument41 pagesInstant Download Ebook PDF Elemental Geosystems 7th Edition PDF Scribdsean.cunningham518100% (52)

- C1 Pronoun and Compression NounDocument15 pagesC1 Pronoun and Compression Noungreeshouse2022No ratings yet

- De Anh Chuyen Nga Phap Trung Chinh Thuc 2021 2022Document8 pagesDe Anh Chuyen Nga Phap Trung Chinh Thuc 2021 2022chauanhinminecraftNo ratings yet

- 1st Term Geography SS 2 Lesson NoteDocument65 pages1st Term Geography SS 2 Lesson Notefabulousfareedah232No ratings yet

- Exploring Physical Geography 3Rd Edition Full ChapterDocument41 pagesExploring Physical Geography 3Rd Edition Full Chapterrose.smith703100% (25)

- Geography 9th Grade ProjectDocument14 pagesGeography 9th Grade Projectyannelajl21No ratings yet

- Gairik .... NatureDocument79 pagesGairik .... NatureGairik BiswasNo ratings yet

- (Dank Cho Thisinh Thi Chuyen Nga, PHDP, Trung) : Thai Gian Lam Bai: 180 Phut, Fchong K I Then Gian Giao deDocument8 pages(Dank Cho Thisinh Thi Chuyen Nga, PHDP, Trung) : Thai Gian Lam Bai: 180 Phut, Fchong K I Then Gian Giao deNguyên Hà Nguyễn100% (1)

- The Development of Glacial Lake OntonagonDocument72 pagesThe Development of Glacial Lake OntonagonStan VittonNo ratings yet

- Reading Practice 4 - Global Warming in New ZealandDocument4 pagesReading Practice 4 - Global Warming in New ZealandBushinshinzNo ratings yet

- Utbk Bahasa Inggris 07 (5 Oktober 2019)Document2 pagesUtbk Bahasa Inggris 07 (5 Oktober 2019)Riska Anggri MNo ratings yet

- Grade 6 - Geography - Landforms of The Earth - Question Bank Answer KeyDocument3 pagesGrade 6 - Geography - Landforms of The Earth - Question Bank Answer KeyPrabha TNo ratings yet

- 2024 03 06 Introduction Lecture Series Climate Protection SS2024Document45 pages2024 03 06 Introduction Lecture Series Climate Protection SS2024Abdullah Khan QadriNo ratings yet

- Noah and The Deluge Chronological HistorDocument194 pagesNoah and The Deluge Chronological HistorStephanos KelilNo ratings yet

- Bcra 14-3-1987Document52 pagesBcra 14-3-1987Cae MartinsNo ratings yet

- UFC 3-220-10N - Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC) Soil Mechanics, 2005Document394 pagesUFC 3-220-10N - Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC) Soil Mechanics, 2005Jong U LeeNo ratings yet

- Alex Maltman (Auth.), Alex Maltman (Eds.) - The Geological Deformation of Sediments-Springer Netherlands (1994)Document367 pagesAlex Maltman (Auth.), Alex Maltman (Eds.) - The Geological Deformation of Sediments-Springer Netherlands (1994)nonogermanoNo ratings yet

- Reference Question Practice 2: Passage 1Document2 pagesReference Question Practice 2: Passage 1Luthfia PramikaNo ratings yet

- Weathering Erosion Deposition - WorksheetDocument4 pagesWeathering Erosion Deposition - Worksheetyasser ammarNo ratings yet

- Respuestas A Las FuerzasDocument11 pagesRespuestas A Las FuerzasZSHADISHNo ratings yet

- M. Altaweel, A. Marsh, S. Mühl, O. Nieuwenhuyse, K. Radner, K. Rasheed, and S. A. Saber, “New Investigations in the Environment, History and Archaeology of the Iraqi Hilly Flanks: Shahrizor Survey Project 2009-2011.” Iraq 74 (2012) 1-35.Document36 pagesM. Altaweel, A. Marsh, S. Mühl, O. Nieuwenhuyse, K. Radner, K. Rasheed, and S. A. Saber, “New Investigations in the Environment, History and Archaeology of the Iraqi Hilly Flanks: Shahrizor Survey Project 2009-2011.” Iraq 74 (2012) 1-35.nerakrendarNo ratings yet

- Kedarnath Disaster: Facts and Plausible Causes: Scientific CorrespondenceDocument4 pagesKedarnath Disaster: Facts and Plausible Causes: Scientific CorrespondenceBIJAY KRISHNA DASNo ratings yet

- Quaternary Break-Out Flood Sediments in The Peshawar BasinDocument24 pagesQuaternary Break-Out Flood Sediments in The Peshawar BasinJonathan RobertsNo ratings yet

- Chap07 Surface Processes On EarthDocument30 pagesChap07 Surface Processes On EarthopulitheNo ratings yet

- Seabed Scour Considerations For Offshore Wind Development On The Atlantic OcsDocument152 pagesSeabed Scour Considerations For Offshore Wind Development On The Atlantic Ocsql21200% (1)

- Instability in Eight Sub Basins of The Chiliwack River Valley, British Columbia, Canada - A CompariDocument10 pagesInstability in Eight Sub Basins of The Chiliwack River Valley, British Columbia, Canada - A CompariMuhammad Rizal PahlevyNo ratings yet

- Practice Test FOURDocument11 pagesPractice Test FOURHua Tran Phuong ThaoNo ratings yet

- GSI OverviewDocument36 pagesGSI Overviewmkshri_inNo ratings yet

- Kamus GeologiDocument98 pagesKamus GeologiTarman Alin S100% (1)