Professional Documents

Culture Documents

the-echr-implications-of-the-investigation-provisions-of-the-draft-competition-regulation

the-echr-implications-of-the-investigation-provisions-of-the-draft-competition-regulation

Uploaded by

Jaqueline MalongaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

the-echr-implications-of-the-investigation-provisions-of-the-draft-competition-regulation

the-echr-implications-of-the-investigation-provisions-of-the-draft-competition-regulation

Uploaded by

Jaqueline MalongaCopyright:

Available Formats

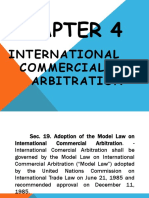

THE ECHR IMPLICATIONS OF THE INVESTIGATION PROVISIONS

OF THE DRAFT COMPETITION REGULATION

ALAN RILEY*

I. INTRODUCTION

In September 2000 the European Commission published its long-awaited

proposed replacement for Regulation 17, the Proposal for a Council

Regulation on the Implementation of the Rules on Competition laid down in

Articles 81 and 82 of the Treaty (hereafter the draft regulation).1 The debate

on the draft regulation has focused on the abolition of the notification system,

the role of the national courts, and the role of the national competition author-

ities (hereafter the NCAs). However, there is one significant overlooked issue,

namely the extent to which the investigation provisions of the draft regulation

comply with the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (hereafter

ECtHR).2 Given the paucity of the ECtHR’s case law in 1961 it is under-

standable that the implications of the European Convention of Human Rights

(hereafter ECHR) for the investigative provisions of what was to become

Regulation 17 were not at that time given any great consideration by the

European Parliament and the Council of Ministers. However, there is now an

extensive human rights case law, developed by the Strasbourg authorities

which, it is argued, casts a major shadow over the Commission’s existing and

proposed investigative powers. It is further argued that the case law of the

European Court of Justice (hereafter ECJ) and the Court of First Instance

(hereafter CFI) in respect of fundamental rights as general principles of law,

does not provide an equivalent standard of protection to that offered by the

ECtHR. Furthermore, this difference in rights protection cannot be ignored by

the Community institutions. Notably, the international conflict provision

contained in Article 307 of the EC Treaty provides defendant undertakings

with the means to trump the investigative provisions of Regulation 17 and the

proposed new investigative powers of the draft regulation with the interna-

tional obligations of the Member States set out in the Convention. Finally, it

is submitted that the Commission can obtain sufficient powers to police the

competition rules effectively without infringing the ECHR, and that the draft

regulation should therefore be amended.

* Butterworths Tolley Research Fellow Centre for Legal Research, Nottingham Law School.

The author would like to thank Ms Kristina Nordlander for her observations on the original text

of this paper. All errors and ommissions are solely the responsibility of the author.

1 COM (2000) 582 Final, 27 Sept 2000.

2 The alternative word ‘Convention’ is also used in this paper to refer to the ECHR.

[ICLQ vol 51, January 2002 pp 55–89]

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

56 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

Section II of this paper outlines the investigative powers of the draft regula-

tion, while Section III considers the standard of fundamental rights protection

offered by the Community legal order in respect of the Commission’s power

to obtain information and its power of inspection. Section IV examines the

ECHR implications of the draft regulation, and section V explains why the

Community institutions cannot ignore the Convention case law without threat-

ening to undermine the legitimacy and effectiveness of the Commission’s

powers in this field. Part six offers an alternative approach to the

Commission’s powers of investigation which would ensure that its powers of

supervision and enforcement were enhanced, but which also make sure that

such powers complied with the Convention.

II. THE POWERS OF INVESTIGATION CONTAINED IN THE DRAFT REGULATION

The draft regulation builds upon the powers already granted to the

Commission under Regulation 17. In the draft regulation the Commission

retains both the power to obtain information and the power to make unan-

nounced inspections by decision. In addition, it sets out a number of signifi-

cant enhancements to both powers.

Article 18 provides the Commission with its most important power to

obtain information from undertakings.3 The powers and procedures of Article

18 are closely modelled on those of Article 11 of Regulation 17. As with

Article 11, Article 18 imposes a two stage procedure on the Commission. It

must first make a request to an undertaking4 to supply information, stating the

legal base of the request, the time limit within which the information is to be

provided, the purpose of the request, and the penalties for supplying incorrect,

incomplete, or misleading information.5 Where an undertaking fails to supply

the information within the time limit or, supplies incomplete information, the

Commission can adopt a decision requiring the information to be supplied on

pain of fixed or periodic penalties under Articles 22 and 23 respectively. The

decision specifies what information is required, fixes a time-limit within

which the information is to be supplied, specifies the penalties for non-compli-

ance, and indicates the right to have the decision reviewed by the Court of

Justice.6 The only significant revision that Article 18 makes to the power to

obtain information is found in paragraph three. In that paragraph lawyers are

permitted to supply the information requested in place of the owners or offi-

3 Art 18(1) also provides that requests for all necessary information may also be made to the

governments and competition authorities of the Member States. However, the obligation to supply

information contained in Art 18(3), and the power to adopt a decision requiring that information

be so supplied on pain of financial penalties, only applies to undertakings and associations of

undertakings.

4 For the purposes of this paper ‘undertaking’ is deemed to include an association of under-

takings, except where the contrary is indicated. 5 Art 18(2).

6 Art 18(4). In fact an application for annulment of an Art 18 decision will be heard by the

CFI. See Art 3(c) of Council Decision 88/591 ECSC, EEC, Euratom, OJ 1989 L317/48.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 57

cers of the undertaking. However, the latter do remain fully responsible if the

information supplied is incorrect or misleading.

The most significant addition to the power of the Commission to obtain infor-

mation contained in the draft regulation is found in Article 19. It provides that:

In order to carry out the duties assigned to it by this Regulation, the Commission

may interview any natural or legal person that may be in possession of useful

information, in order to ask questions relating to the subject-matter of an inves-

tigation and recording the answers.7

The power is not limited to representatives of suspect undertakings. It

could, for example, be used to interview and record the evidence of the repre-

sentatives of victim undertakings. At first sight it would appear that the powers

contained in Article 19 can only be exercised in respect of undertakings who

are likely to agree to be interviewed, such as victims of anti-competitive prac-

tices. This is because, curiously, the draft regulation provides no power of

decision and no sanction power to underpin such decisions, by comparison

with both Articles 18 and 20. By contrast the proposals set out in the White

Paper Modernisation of the Rules Implementing Articles 85 and 86 of the EC

Treaty (hereafter the 1999 Modernisation White Paper), which preceded the

draft regulation, did provide for a power to ask questions backed by financial

sanctions.8 It is difficult to see how the Commission can realistically expect

representatives of suspect undertakings to attend interviews unless they are

required to attend on pain of significant financial penalties being imposed. It

may be, therefore, that the lack of a fining power is an oversight. However, the

absence of any power of decision in Article 19 suggests that the lack of any

fining power is deliberate. It is possible to conceive that the Commission’s

draftspersons might have forgotten to include a reference to financial sanc-

tions in Article 19. It is very unlikely that they also forgot to include a power

of decision requiring specified persons to attend an interview, indicating a

time limit and the subject of the proposed interview, all of which would

presumably be necessary before any fine could be imposed.9 If that latter view

is correct then Article 19 is of extremely limited utility to the Commission.10

7 The author has not made a mistake. The quotation is accurate. Unfortunately, the English

version of the draft regulation, in respect of Art 19, is grammatically incorrect. Preferably the

entire Article should be rewritten both to correct the grammar and improve the clarity of the text.

8 The European Commission, Brussels, April 1999, Commission Programme no 99/027.

9 For example, without a time limit the Commission would not be able to impose a fine, as it

would have to give a time within which the obligation would have to be performed.

10 It could be argued that the reason why Art 19 does not grant the Commission a power of

compulsion, as envisaged in the Modernisation White Paper, is that in putting together the draft

regulation the Commission has taken account of the judgment of the ECtHR in Saunders v United

Kingdom [1996] 16 EHRR 297. Saunders suggests that the imposition of penalties as a result of

a refusal to answer questions can constitute a violation of Art 6 of the ECHR. The case is

discussed in detail in part 4. However, it is difficult to see how the Commission’s draftspersons

could have taken account of Saunders in relation to Art 19, when Art 18 raises includes a power

of compulsion, which, as it is argued below, itself infringes Art 6 of the ECHR and the rule in

Saunders.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

58 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

The most significant development to all of the Commission’s powers of

investigation in the draft regulation is contained in Article 20. Virtually all the

features of the Commission’s power of inspection, as set out in Article 14 of

Regulation 17, are reproduced in Article 20. The Commission is again

provided with broad powers to make all necessary investigations into under-

takings.11 Officials are empowered to examine the books and other business

records, irrespective of the medium in which they are stored,12 to take copies

of or extracts from the documents examined;13 and to enter premises, land, and

means of transport of undertakings.14 Article 20 also provides for an almost

identical procedure to that found in Article 14. Hence the Commission has a

choice between exercising its powers by means of a written authorisation15 or

by decision.16 In both cases the subject-matter and purpose of the inspection

must be specified, together with the penalties for providing incomplete

answers. In the case of an inspection by decision the additional penalties for

refusal to comply with the decision must be specified along with the right of

the undertaking to have the decision reviewed by the Court of Justice.17

There are three principal additional powers of which the first two are

entirely new. First, in Article 20(2)(b) the Commission obtains the power to

enter any other premises, including the homes of directors, managers and other

members of staff of the undertaking concerned, in so far as it may be suspected

that business records are being kept there. Secondly, in Article 20(2)(e)

Commission officials may seal any premises or business records during the

inspection. Thirdly, in Article 20(2)(f) its power to ask questions during

inspections is extended. Under Article 14(1)(c) of Regulation 17 it could only

ask for oral explanations on the spot. It was unclear whether the Commission

could only ask questions relating to the documents being examined, for exam-

ple, for assistance in understanding technical details or abbreviations, or

whether a much wider class of questions could be asked.18 The new provision

resolves the confusion by clearly imposing an obligation on undertakings to

answer a broad range of questions on the subject matter of the investigation.

Under the draft regulation the Commission will now have the power:

to ask any representative or member of staff of the undertaking or association of

undertakings for information relating to the subject-matter and purpose of the

inspection and to record the answers.

Article 14(6) of Regulation 17 and Article 20(6) both provide for the Member

11 Art 20(1).

12 Art 20(2)(c). It should be noted that the phrase ‘irrespective of the medium in which they

are stored’ is a gloss added by the draft regulation to take account of the modern ability to store

and transmit data electronically, and, not found in Art 14 of Regulation 17.

13 Art 20(2)(d). 14 Art 20(2)(a).

15 Art 20(3). 16 Art 20(4).

17 As with Art 18, the application for annulment of the decision would in fact be brought before

the CFI.

18 Kerse, EC Antitrust Procedure, 4th edn (Sweet & Maxwell, 1998) para 3.34.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 59

State authorities to assist the Commission when an undertaking opposes an

inspection. However, the latter Article goes on to oblige the Member States to

request, where appropriate, the assistance of the police in order to enable the

Commission to conduct its inspection.

Article 20(6), (7) and (8) also set out the scope for judicial authorisation of

Commission Article 20(4) decisions. There are three main features. First,

Article 20(6) provides that, if national law requires authorisation from the

judicial authority before the assistance of the police can be called upon, such

authorisation may be applied for as a precautionary measure. The 1999

Modernisation White Paper set out two proposals for judicial authorisation.

The first provided for prior authorisation by the CFI, the second for authori-

sation by the national courts.19 Article 20(6), by contrast, provides for no form

of automatic prior judicial authorisation. Instead it merely sets out an option

for a Member State whose national law requires that judicial authorisation be

obtained prior to an inspection. Presumably, where national law requires no

judicial authorisation, the Member State can proceed directly to assist the

Commission by forcing entry to the undertaking’s premises.20 Secondly,

Article 20(7) requires that judicial authorisation is obtained before an Article

20(4) inspection is to take place where the inspection is to be carried on

domestic premises. Thirdly, Article 20(8) sets out the terms under which

national courts can supervise the enforcement of the inspection decision. It is

emphasised that the power of review extends only to establishing that the

Commission decision is authentic, and that the envisaged enforcement

measures are neither arbitrary nor excessive. It goes on to provide that the

national court may not review the necessity for the inspection or require

further information other than that set out in the Commission decision. Article

20(8) expressly provides that the lawfulness of the decision rests solely in the

hands of the ECJ. Essentially, the draft regulation is drawing directly upon the

judgment of the Court of Justice in Hoechst v Commission, where it set out the

scope of the power of review of the national courts over Commission inspec-

tion decisions. The Hoechst judgment is discussed extensively in part three.21

Articles 22 and 23 underpin the power to obtain information and the power

of inspection by granting the Commission the power to impose fines and peri-

odic penalty payments for providing incomplete, incorrect or misleading

19 1999 Modernisation White Paper, op cit, para 111.

20 No judicial authorisation is required in the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Italy, and Austria,

prior to national enforcement of an Art 20(4) decision. 1999 Modernisation White Paper, op cit,

para 110, n 64.

21 Case 46/87 and 227/88 [1989] ECR 2859. The draft regulation, however, does not provide

uniform Community standards when National Competition Authorities acting on their own initia-

tive seek to obtain information by inspection of premises for themselves, or in respect of other

NCAs. Art 21(1) expressly leaves the power of inspection as a matter of national law when one

NCA is acting for another NCA. No direct reference is made to own initiative inspections by

NCAs. However, the lack of any reference in the draft regulation infers that such inspections are

also to be left to be governed by national law.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

60 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

information, or for refusal to submit to a decision. Such fines are also a feature

of Regulation 17. However, inflation has eroded the value of these fines.

Currently Article 15(1) of Regulation 17 permits the Commission to levy a

fine of between ʗ=100 and ʗ=5000 where an undertaking intentionally or negli-

gently supplies incorrect or misleading information in response to a request

made pursuant to an Article 11(3) request for information, an Article 11(5)

decision or in respect of an Article 14(3) decision.

Equally, Article 16(1) permits the Commission to impose periodic penalty

payments in respect of such behaviour as well as refusal to submit to an Article

11(5) decision requiring the production of information or Article 14(3) inspec-

tion decision. The periodic payments were set at between ʗ=50 and ʗ=1000. The

draft regulation has restored the effectiveness of the Commission’s fining power

and protected it against inflation by providing that the fixed penalty shall be set

at up to 1 per cent of annual turnover of the undertaking concerned in the preced-

ing business year.22 The periodic penalty payment is fixed at a maximum of 5

per cent of the average daily turnover of the undertaking concerned.23

The draft regulation does not just tidy up the investigation powers of

Regulation 17. For example, Article 19, despite its lack of any sanction power

is a significant development of the scope of the Commission’s power to obtain

information. Of even greater importance is Article 20(2)(b) giving the

Commission power to enter private premises. Clearly this power will assist the

Commission in blocking undertakings sidestepping an inspection by holding

incriminating company documents on private premises.24 It is also clear that

Article 20(2)(f) will permit the Commission to ask a much wider range of

questions than hitherto, without the threat of challenge from the undertakings’

legal representatives arguing that the power to ask questions is strictly limited.

One outcome which is not immediately obvious, however, is the impact of

the restoration of the Commission’s fining powers. There are two aspects to

this issue. First, the restoration of the fining power may encourage the

Commission to make more use of Article 18(4) decisions requesting informa-

tion. Where the Commission knows the information exists it may save

manpower, as issuing a decision requires fewer resources than sending an

inspection team to the premises. Secondly, in respect of periodic penalty fines

the Commission can impose more than one obligation on an undertaking and

then attach a periodic penalty fine to each obligation. For example, in

Commercial Solvents v Commission the Commission imposed two obligations

on Commercial Solvents and its subsidiaries, first to resupply the alleged

victim of the supposed abusive practices, and secondly to submit within two

months proposals for continued supplies to the alleged victim.25 In each case

22 Art 22. 23 Art 23.

24 In the Explanatory Memorandum to the draft regulation the Commission explains that in

recent cases it has come across evidence that incriminating documents have been held on the

private premises of company officials, Draft Regulation, op cit, 25.

25 Cases 6 and 7/73 [1974] ECR 1281.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 61

the Commission imposed a periodic penalty payment of ʗ=1000 per day. The

ECJ upheld this practice, albeit sub silentio.26 Given that the draft regulation

will permit the Commission to impose a fine of up to 5 per cent of average

daily turnover, undertakings could face the prospect of several obligations

each involving a fine of up to 5 per cent of average daily turnover. However,

it may be that if the Commission sought to impose such significant burdens on

undertakings, the ECJ would reconsider the case law. The willingness of the

Court to accept that each obligation attracted a periodic penalty fine in 1974

may not have been unconnected with the fact that the fines, even at that point

in time, were extremely low.

III. FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS PROTECTION FOR UNDERTAKINGS WITHIN THE

COMMUNITY LEGAL ORDER

It is true that until the coming into force of the Maastricht Treaty in November

1993 fundamental rights were not recognised in the various Community

Treaties.27 However, from the early 1960s the Court of Justice began to

develop a fundamental rights jurisprudence as part of the general principles of

Community law. In Opinion 2/94 28 and Kremzow v Austria 29 the Court re-

stated its fundamental rights case law that such rights form an integral part of

the general principles of Community law. The Court explained that, in order

to ensure that fundamental rights are adhered to within the Community legal

order, it relied upon constitutional traditions of the Member States and the

guidelines supplied by international treaties and conventions on the protection

of human rights on which the Member States have collaborated or to which

they are signatories. In particular, the Court noted that the ECHR has a special

significance as a source of guidance.30

As early as 1980 undertakings sought to use the ECtHR’s fundamental

rights jurisprudence to challenge the Commission’s powers of investigation.

In National Panasonic, Article 14(3) of Regulation 17, the Commission’s

power of inspection, was challenged on grounds that it infringed the under-

26 For a further discussion see Kerse, op cit, para 7.46. As he notes, Commercial Solvents is

‘an old but instructive case’.

27 Alston and Weiler, ‘An Ever Closer Union in Need of a Human Rights Policy: The

European Union and Human Rights’, 9 in Alston (ed), The EU and Human Rights (Oxford: OUP,

1999).

28 [1996] ECR I-1759.

29 C-299/95 [1997] ECR I-2629.

30 Opinion 2/94 op cit, para 33, Kremzow, ibid, para 14. Art 6(2) of the Treaty on European

Union also provides that ‘the Union shall respect fundamental rights, as guaranteed by the

European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms signed in

Rome on 4 Nov 1950 and as they result from the constitutional traditions common to the Member

States, as general principles of Community law.’ However, as the last clause of the sentence that

makes up the art indicates, Art 6(2) re-states the position in respect of fundamental rights as devel-

oped by the Court of Justice. Clearly this re-statement will have implications for the operation of

the other pillars of the Union, but it is difficult to see how it adds to the protection already

provided by the ECJ’s case law.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

62 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

takings fundamental rights, and in particular Article 8 of the ECHR.31 In that

case the ECJ rejected the argument raised by the undertaking, holding instead

that, so long as the Commission complied with the terms of Article 14(3),

there was no infringement of Article 8.32

Since 1980 undertakings have regularly raised fundamental rights, and

more specifically ECHR arguments, to challenge Commission powers of

investigation.33 In two cases, Orkem v Commission34 and Hoechst v

Commission,35 the Court provided a detailed response to the challenges of

undertakings in respect of the power to obtain information and the power of

inspection. These judgments have since been followed by the CFI.36

A. The Power to Obtain Information

In Orkem, the issue was raised as to whether the privilege against self-incrimi-

nation operated as a general principle of Community law to delimit the applica-

tion of Article 11. The ECJ rejected that argument. It took the view that, where

the privilege against self-incrimination existed in the laws of the Member States,

it applied only in relation to criminal proceedings. Furthermore, there was no

such principle common to the laws of the Member States that could be relied

upon by legal persons in the economic sphere, in particular, with regard to

infringements of competition law.37 Finally, the ECJ observed that neither the

wording of Article 6, nor the decisions of the ECtHR, indicated that that Court

upheld the right not to give evidence against oneself.38

The ECJ in fact placed a duty upon undertakings to co-operate actively with

the Commission, in making available all information relating to the subject

matter of the investigation. It held that the Commission is entitled:

in order to preserve the useful effect of Article 11 to compel an undertaking to

provide all necessary information concerning such facts as may be known to it,

if necessary such documents relating thereto as are in its possession even if the

31 Case 136/79 [1980] ECR 2033. 32 National Panasonic, ibid, paras 19 and 20.

33 The question of self-incrimination was raised even earlier. When the initial draft of what was

to become Regulation 17 was considered by the European Parliament it voted to recommend the

inclusion of a provision against self-incrimination. However, the Council did not incorporate the

Parliament’s amendment into the Regulation. See Edward, ‘Constitutional Rules of Community

Law in EEC Competition Cases’ (1989–1990) Fordham ILJ, 112, 123, see also Kerse, op cit, para

3.44 and Advocate-General Warner in Case 155/79 AM&S Europe v Commission [1982] ECR

1575, 1621.

34 Case 374/87 [1989] ECR 3283. 35 Hoechst, op cit.

36 In respect of Orkem, see Case T-34/93 Société Générale v Commission [1995] ECR II-545;

Case T–112/98 Mannesmann Werke AK v Commission, 20 Feb 2001, not yet reported, and Case

C–294/98P Metsa Serla Og Y 6 Nov 2000 not yet reported. In respect of Hoechst, see Joined

Cases T-305/94, T-306/94, T-307/94, T-313/94, T-314/94, T-315/94, T-316/94, T-318/94, T-

325/94, T-328/94, T-329/94 and T-335/94, LVM and Others v Commission (PVC), [1999] ECR II

931, paras 405 to 407. Opinion of Advocate-General Lever, C–353/99P Council v Hautala, 10

July 2001, not yet reported. Opinion of Advocate-General Mischo Case C–94/00 Roquette Freres

v Directeur Generale de la Concurrence 20 Sept 2001 not yet reported.

37 Orkem, para 29. 38 Orkem, para 30.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 63

matter may be used to establish against it or another undertaking, the existence

of anti-competitive conduct.39

However, the Court did accept that in order to protect the rights of the defence

during the preliminary investigation a limited privilege against self-incrimina-

tion existed in Community law. Hence:

the Commission may not compel an undertaking to provide it with answers

which might involve an admission on its part of the existence of an infringement

which it is incumbent on the Commission to prove.40

The limited nature of this privilege is illustrated by its application in

Orkem. Hence ‘Section I’ questions, which related to meetings of producers,

and were intended to secure factual information on the circumstances in which

such meetings were held and the capacity in which the participants attended

them, together with a requirement of disclosure of documents in the undertak-

ing’s possession were not open to criticism.41 Equally ‘Section II’ questions,

relating essentially to the measures taken in order to determine and maintain

price levels satisfactorily to all the participants at the meetings, were consid-

ered by the ECJ as not open to criticism in so far as the Commission sought

factual clarification as to the subject-matter and implementation of those

measures. It was only when the questions turned to the purpose of the action

taken and the objective pursued by those measures that the Commission fell

foul of the Community privilege. For example, sub-question 1(c), which

sought clarification on ‘every step and concerted measure which may have

been envisaged or adopted to support such price initiatives’, was condemned

as compelling the undertaking to acknowledge its participation in an agree-

ment infringing Article 81(1).

As the Commission has itself observed, this restriction only has the effect

of preventing it from asking leading questions.42 Essentially, as Kerse

observes, the extent of the privilege is narrow and, while it may serve to avoid

oppressive behaviour, it will in practice place no inhibition on the Commission

provided that leading questions are avoided.43

B. The Power of Inspection

In Hoechst the Court found itself confronted by a vigorous challenge to Article

14(3) based upon Article 8 of the ECHR. This time it took a different approach

to that which it took in National Panasonic. The Court did not attempt to

39 Orkem, para 34.

40 Orkem, para 35.

41 Orkem, para 37.

42 Dealing with the Commission, Notification, Complaints, Inspections and Fact-Finding

Powers under Arts 85 and 86 of the EEC Treaty (European Commission, 1997) para 4.1. (here-

after Dealing).

43 Kerse, op cit, para 3.44.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

64 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

reconcile Article 14(3) with Article 8, but instead rejected the notion that

Article 8 could apply to business premises:

the protected scope of that Article is concerned with the development of a man’s

personal freedom and may not therefore be extended to business premises.

Furthermore, it should be noted that there is no case law of the European Court

of Human Rights on the subject.44

Furthermore, as in cases involving an Article 11 decision, it ruled that an

Article 14 decision providing for an inspection of business premises places a

duty of active collaboration upon undertakings.45

However, it was clear, that notwithstanding the inapplicability of Article 8, a

number of safeguards remained for defendant undertakings. Firstly, as the ECJ

in Hoechst pointed out, the requirement in Article 14(2) and (3) that the

Commission state the purpose and subject-matter of the investigation constituted

a major safeguard of the rights of the defence.46 Secondly, the Commission

guidelines indicate that it accepts an undertaking’s right of access to a lawyer.47

It is true that the Commission takes the view that the presence of a lawyer is not

a prerequisite.48 However, the Commission has indicated that it will wait a

reasonable time for a lawyer to arrive.49 Thirdly, there is the protection given to

communications between lawyers and their client undertakings. In AM&S

Europe v Commission the ECJ held that the protection extended to independent

lawyers entitled to practise the profession of law in one of the Member States.50

Fourthly, Regulation 17 itself provides an additional safeguard in the shape of

Article 20 which imposes a restriction on the use of material found, and confi-

dentiality obligations on the Commission in relation to such material.51 Fifthly,

it can also be argued that the Community law principle of proportionality

protects undertakings against oppressive behaviour, and may provide the means

of constructing additional safeguards for undertakings under investigation.52

44 Hoechst, op cit, para 30. 45 Orkem, op cit, para 27.

46 There is also the safeguard in relation to an Art 14(3) decision that, as required by Art 253

of the EC Treaty, a decision must be reasoned. However, in relation to an Art 14(3) decision, this

requirement has been interpreted as only requiring the Commission to comply with the terms of

Art 14 (3) itself, i.e. that the decision states the subject-matter and purpose of the investigation,

the appointed date on which it is to begin, the penalties that may be imposed, and the right of

review by the CFI. National Panasonic, op cit, para 25.

47 Dealing, op cit, para 5.5, sub-para 1. 48 Ibid, sub-para 2.

49 Ibid. However, if lawyers are available on site, the Commission may proceed with the inves-

tigation without waiting for the arrival of external lawyers. Explanatory Note to Authorisation to

Investigate in Execution of a Commission Decision under Art 14(3) of Regulation no.17/62, para

6. see Kerse, op cit, App G.

50 Case 155/79 [1982] ECR 1575. In Case T-30/89 Hilti AG v Commission [1990] ECR II 163,

the CFI held that legal professional privilege extended to documents drawn up by in-house

lawyers summarising the advice of outside counsel.

51 For a discussion of the extent of confidentiality and use restrictions, see Kerse, op cit, paras

3.45 and 3.46.

52 It is submitted that applying the principle of proportionality to a Commission investigation

would mean that only the minimum interference consonant with the objectives of the search are

permitted. In practice this would require Commission officials, to seek to minimise the impact of

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 65

Furthermore, additional safeguards are put in place when the Commission

is faced by opposition to its decision requiring entry. The Commission cannot

itself force entry to the premises of undertakings. Article 14(6) requires the

Member States to afford the Commission the necessary assistance. In Hoechst,

the Court held that the obligation of the Member States was to ensure that the

Commission’s action would be effective.53 This obligation of effectiveness

includes the national authorities obtaining a court order, where necessary, to

enforce a Commission decision.

Two safeguards exist to protect an undertaking in such a situation. First, it

can always challenge the legality of the Article 14 decision before the CFI54.

Secondly, in Hoechst the ECJ held that it is within the powers of the relevant

national body before it orders enforcement measures to:

(a) satisfy itself that the decision ordering the investigation is authentic;

(b) consider whether the measures of constraint envisaged are arbitrary or

excessive having regard to the subject matter of the investigation, and

(c) be sure that the rules of national law are complied with in the applica-

tion of the enforcement measures.55

Once the measures of enforcement have been issued, the Commission, with

the assistance of the Member State, will be able to force entry. In such a situ-

ation, the ECJ has ruled that the Commission has a general power of search.56

The relationship approach of a normal investigation does not apply.

C. The Investigative Provisions of the Draft Regulation and the

Fundamental Rights Case Law of the Court of Justice

It is clear from the above discussion that Articles 18, 19, and 20 of the draft

regulation comply with the fundamental rights standards developed by the

Court of Justice in Orkem and Hoechst. Indeed that case law has provided a

direct source for the development of the Commission’s investigative powers.

In particular, in Article 20(8) the draftspersons of DG Competition have relied

on the ruling of the ECJ in Hoechst to provide them with the standard for judi-

cial authorisations by national courts of Article 20(4) inspection decisions.

IV. THE ECHR IMPLICATIONS OF THE INVESTIGATIVE PROVISIONS OF THE

DRAFT REGULATION

This part first considers the issue of whether the EC competition rules are

their investigation on the operation of the undertaking and the business premises being investi-

gated. For example, by handling and refiling documents carefully, or by taking a systematic, area

by area approach to file examination, to minimise the disruption to business operations.

53 Hoechst, op cit, para 33.

54 However, as explained below, there is considerable doubt as to the efficacy of this proce-

dure to protect the rights of undertakings, see part 4.3.

55 Hoechst, op cit, para 32. 56 Ibid, para 27.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

66 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

criminal for the purposes of the Convention. Then two substantive issues are

discussed. First, the compatibility of Articles 18, 19 and 20(2)(f) of the draft

regulation with Article 6 of the ECHR and the ECtHR case law on self-incrim-

ination and secondly, the compatibility of the power of inspection contained

in Article 20 with Article 8 of the Convention.

A. Whether the EC Competition Procedures and Penalties are Criminal for

the Purposes of the ECHR

The first issue to be considered is whether the investigatory procedures and the

penalties envisaged in the draft regulation are criminal in nature for the

purposes of the Convention. If these procedures and penalties are deemed

criminal, a far wider range of issues come into play than just the question of

whether the compliance of the power of inspection contained in Article 20,

with Article 8 of the ECHR.57 In particular, the role of the rule against self-

incrimination and Articles 18, 19 and 20(2)(f) of the draft regulation.

In Engel v Netherlands the ECtHR accepted that the Convention permits

Contracting States in the performance of their functions as guardians of the

public interest to maintain or establish a distinction between criminal and

regulatory law. However, it went on to point out that the definition of a crim-

inal charge, for the purposes of the Convention, is autonomous. It argued that

to have permitted the Contracting States to provide definitions of criminal,

regulatory, and disciplinary law, and to have obliged the Court to follow such

definitions, would result in the undermining of the objective and purpose of

the Convention.58 The ECtHR then set out the criteria for the autonomous

definition of ‘criminal charge’ under the Convention. It identified three core

criteria. First, the classification of the offence under national law, secondly,

the nature of the offence, and thirdly, the severity of the penalty.59

The application of the Engel criteria in a regulatory context is demonstrated

by Bendenoun v France.60 There the applicant argued that the national

proceedings in which tax surcharges were imposed upon him violated Article

6(1). The French government argued that the proceedings were not criminal,

having instead all the hallmarks of an administrative penalty. The Court

disagreed with the French government emphasising first, the nature of the

offence. It was of general application, as the offences under which Bendenoun

was charged covered all citizens in their capacity as tax payers, and not a given

group with a particular status. In addition, the tax surcharges were intended

not as pecuniary compensation for damage but essentially as a punishment to

57 If the Community competition procedures are deemed criminal for the purposes of the

Convention a number of other issues not within the scope of this paper could also be raised.

Notably whether the procedure by which the Commission determines ‘guilt’ in a decision without

first holding a hearing that complies fully with Art 6 (1) ECHR constitutes a violation of Art 6(1)

itself or Art 6(2).

58 [1979–80] 1 EHRR 647, para 81. 59 Engel, op cit, para 82.

60 [1994] 18 EHRR 54.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 67

deter re-offending. Furthermore, the penalties were imposed under a general

rule, whose purpose was both deterrent and punitive. Secondly, in respect of

the severity of the penalty, the surcharges were very substantial, amounting to

FrF 422,534 and FrF 570,398.

Having weighed the various factors in the case, the Court noted the

predominance of those which had a criminal connotation. None of them was

decisive on its own, but taken together made the nature of the ‘charge’ in ques-

tion a criminal one within the meaning of Article 6(1).61

The case law of the ECHR has also considered the status of price fixing and

competition rules. In Deweer v Belgium 62 the Court held that a prohibition on

price fixing could be criminal in nature for the purposes of the Convention.63

Far more pertinently, in Stenuit 64 the fine was imposed upon the company

for engaging in anti-competitive practices. The fine was imposed by the

French Minister of Economic and Financial Affairs under national competi-

tion law. Stenuit, having exhausted national procedures, applied to the

Strasbourg authorities. The company argued that it had been subject to a crim-

inal charge and that its right to a fair hearing had been violated. The European

Commission of Human Rights (hereafter CHR) made two major points.65

First, in respect of the nature of the penalty, that the aim pursued by the

national competition law was to maintain free competition within the French

market. The law in question consequently affected the general interests of

society that are normally protected by criminal law. Secondly, with regard to

the severity of the penalty, that the sum imposed, FrF 50,000, was not in itself

negligible. But above all there was the fact that the maximum fine, i.e. the

penalty to which those responsible for the infringements made themselves

liable, amounted to 5 per cent of annual turnover. This, the Commission

argued, revealed clearly that the penalty in question was intended to be a deter-

rent.66

When the EC Competition rules as envisaged under the draft regulation are

considered in the light of the case law of the ECHR, the inescapable conclusion

is that, for the purposes of the ECHR, the procedures and penalties are crimi-

nal in nature. First, as the Court in Engel 67 pointed out, legislative provisions,

such as the Article 15(4) statement that Commission fines are not of the crim-

inal law nature, cannot be decisive. Secondly, the criteria provided by the Court

in Engel, Benedenoun, and Stenuit strongly support the argument that the EC

competition procedures are criminal in nature. In respect of the nature of the

‘offences’ under EC competition law, it is clear that the aim of the EC compe-

tition rules, as with the criminal law, is to protect the general interests of soci-

ety. In the case of the Community competition rules, the general societal aim is

61 Bendenoun, ibid, para 47. 62 [1979–1980] 2 EHRR 439.

63 In Deweer, the Court emphasised the punitive character of the impugned regulations as a

factor weighing heavily in its decision as to their criminal law character, op cit, para 46.

64 Stenuit v France [1992] 14 EHRR 509.

65 It should be noted that this case was settled before it reached the Court.

66 Stenuit, op cit, paras 60 to 67. 67 Engel, op cit, para 81.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

68 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

the protection of the competitive process and the integrity of the single market.

These rules are of general application, applying across the whole of economic

activity. Furthermore, substantial penalties can be imposed of up to 10 per cent

of turnover, double that of the French competition law in the Stenuit case. Nor

has the Commission failed to use these powers. Its largest individual fine so

far stands at ʗ=462 million, imposed on Hoffman la Roche.68 Furthermore, the

fines that are imposed are intended to deter. As the Commission points out in

its Notice on Co-operation between National Courts and the Commission in

applying Articles 85 and 86 of the EC Treaty, (hereafter, the National Courts

Notice), the fines that are imposed have no compensatory element.69 In addi-

tion, as the Commission has pointed out in numerous reports and studies, the

aim is to punish and deter.70

Furthermore, the EC competition rules have, over the years since

Regulation 17 came into force, gained an additional attribute of criminal law.

The practices that the rules are designed to prevent have increasingly come to

be seen as illegitimate and odious by consumers, politicians, public officials

and business executives themselves.71 It is therefore submitted that the proce-

dures and penalties as set out in the draft regulation are criminal in nature for

the purposes of the Convention.

B. The Power to Obtain Information in Articles 18, 19 and 20(2)(f)

and the Rule Against Self-Incrimination

The key Convention case in relation to the privilege against self-incrimination

is Saunders.72 The Saunders case arose as a result of statements made under the

UK Companies Act to Department of Trade inspectors by the former Guinness

chairman Ernest Saunders. The case did not revolve around the application of

Article 6 to the DTI procedure, but around the use of the statements made in a

68 Commission imposes fines on the vitamin cartel. Commission press release 21 Nov 2001.

As Kerse observes, fines in millions of =ʗs are no longer rare. Kerse, op cit, para 7.27.There he lists

the most recent, and heaviest, individual and collective fines. It should be noted that if Hoffman

la Roche had not obtained leniency for its co-operation the fine would have been 50% higher i.e.

ʗ=924 rather than ʗ=462 million.

69 OJ 1993 C 39/6, para 13.

70 1997 Annual Competition Report (The European Commission, 1998), para 48.

71 For example, the UK Institute of Directors has recently established a Chartered Director

qualification. In order to become and remain a Chartered Director it is necessary to agree to, and

comply with, a code of conduct. Art 5 of which requires that CDs comply with ‘relevant laws,

regulations and codes of practice, refrain from anti-competitive practices.’ A parallel disciplinary

code provides a mechanism for sanctions against CDs who infringe the code of conduct. See IOD

Code of Conduct and IOD Disciplinary Code (IOD, 1998).

72 Saunders, op cit. The ECtHR, in the earlier case of Funke v France [1993] 16 EHRR 297,

took a much broader approach to the rule against self-incrimination. In particular, the Court indi-

cated that even an order requiring the production of documents and not just testimony infringed

Art 6. However, there was little reasoning in the judgment and the CHR opposed the conclusions

of the Court. The ruling in Saunders appears to implicitly overrule Funke. For a further discus-

sion of Saunders see Riley ‘Saunders and the Power to Obtain Information in European

Community and United Kingdom Competition Law’ (2000) 25 ELRev 264.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 69

subsequent complex fraud trial, at the conclusion of which Mr Saunders was

convicted.

The ECtHR took the view that the right to silence and the right not to

incriminate oneself were generally recognised international standards, which

lay at the heart of the notion of a fair procedure under Article 6. It emphasised

that the right not to incriminate oneself presupposes that the prosecution in a

criminal case seek to prove its case against the accused, without resort to

evidence obtained through the methods of coercion or oppression in defiance

of the will of the accused.73 It held that the right not to incriminate oneself was

primarily concerned with respecting the will of an accused person to remain

silent. The Court argued that it was commonly understood in the legal systems

of the Contracting Parties to the Convention and elsewhere, that the right does

not extend to the use in criminal proceedings of material which may be

obtained from the accused through the use of compulsory powers, but which

has an existence independent of the will of the suspect such as, inter alia, docu-

ments acquired pursuant to a warrant, breath, blood and urine samples, and

bodily tissue for the purpose of DNA testing.74

The ECtHR argued that, in considering whether the use made by the pros-

ecution of the statements obtained from Saunders amounted to an unjustifiable

infringement of the privilege, it was necessary to determine whether he had

been subject to compulsion to give evidence, and whether the use of his testi-

mony at trial had infringed the basic principles of a fair procedure. It was clear

from the Companies Act that Saunders was subject to legal compulsion to give

evidence, and that a refusal could result in a finding of contempt and conse-

quent imposition of fines or a period of imprisonment.75

In relation to the infringement of the basic principles of a fair procedure,

the UK had argued that nothing said by Saunders in the statements was incrim-

inating. The statements were either exculpatory or, which, if true, would

confirm his defence. The Court rejected this argument. First, some of

Saunders’ answers were in fact of an incriminating nature in the sense that

they contained admissions to knowledge of information which tended to

incriminate him. Secondly, it argued that the right not to incriminate oneself

cannot reasonably be confined to statements or admissions of wrongdoing, or

to remarks which are directly incriminating. Testimony obtained under

compulsion which appears on the face of it to be of a non-incriminating nature,

73 Saunders, para 68.

74 Ibid, para 69. In the recent case of PK & JH v United Kingdom the Court accepted that

‘voice samples’, recordings taken when the plaintiffs were unaware of such recordings taking

place did not constitute an infringement of Article 6, and were akin to the taking of blood on DNA

samples, 25 Sept 2001, not yet reported.

75 Ibid, para 70. Saunders was obliged under ss 434 and 436 of the Companies Act 1985 to

answer the questions put to him by the DTI Inspectors. A refusal by the applicant to answer the

questions put to him could have led to a finding of contempt of court and the imposition of a fine

or committal to prison for up to two years. It was no defence to such a refusal that the questions

were of an incriminating nature.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

70 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

such as exculpatory remarks or mere information on questions of fact, may

later be deployed in criminal proceedings in support of the prosecution case.

For example, it could be used to contradict or cast doubt upon other statements

of the accused or evidence given by him during the trial, or to otherwise under-

mine his credibility.76 Furthermore, the Court observed that the admissions

made by Saunders must have exerted additional pressure on him to give testi-

mony during the trial, rather than exercise his right to remain silent.77

The Court went on to leave open the question of whether the right not to

incriminate oneself is absolute, or whether infringements of it may be justified

in particular circumstances.78 However, it rejected the UK argument that the

complexity of corporate fraud could justify such a marked departure from one

of the basic principles of a fair procedure. It held that Article 6 applied to types

of criminal offences without distinction, from the most simple to the most

complex.79

There are two notable features of Saunders. First, orders requiring the

production of documents are permitted, subject to the authority in question

obtaining a warrant. Secondly, the breadth of what constitutes an incriminat-

ing statement. It is in no way limited to direct admissions as in Orkem, but

applies to factual statements and even exculpatory ones.

It could be argued that the Saunders rule is limited to the use of statements

in criminal trials and does not apply to investigatory procedures where there

are compulsory powers to obtain evidence.80 It is true that in Fayed the Court

ruled that Article 6 did not apply to the same Companies Act procedure as

deployed in Saunders. However, this was because the DTI inspectors were

investigators only and not adjudicators.81 That would not be the case where

the purpose of the investigatory procedure was to provide evidence for a

conviction, and the investigation and prosecution were carried out by the same

body. In such circumstances, it is submitted that the Saunders rule would be

applied by the ECtHR.82

Clearly, under the Saunders rule, the ability of DG Competition to use

Articles 18, 19, and 20(2)(f) against suspect undertakings is seriously under-

76 Ibid, para 71. 77 Ibid, para 73.

78 Ibid, para 74. It should be noted that in John Murray v United Kingdom [1996] 22 EHRR

29, the ECtHR took the view that the right to silence was not absolute and that inferences could

be drawn in certain circumstances, para 47.

79 Saunders, para 75.

80 Davies, ‘Self Incrimination, Fair Trials and the Pursuit of Corporate and Financial

Wrongdoing’, in The Impact of the Human Rights Bill on English Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1998), ed Markesinis, 31, 35.

81 Fayed v United Kingdom [1994] 18 EHRR 221.

82 In I.J.K., G.M.R. and A.K.P v United Kingdom, [2001] EHRR 11, not yet reported, in a

further set of Guinness defendants sought to challenge their convictions before the Strasbourg

authorities. The ECtHR in that case did take the view that a legal requirement for an individual to

give information demanded by an administrative body did not necessarily infringe Art 6 of the

ECHR, para 100. However, as explained above this gloss on the rule in Saunders is of little assis-

tance to the Commission where the purpose of the investigatory procedure is to provide evidence

for a prosecution and subsequent conviction.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 71

mined. While DG Competition can still request documents under Article 18(3)

it cannot, following a refusal, go to the second stage and require documents to

be produced and impose penalties if such documents are not produced. Article

18 would have to be amended so that DG Competition first had to obtain a

warrant from a court, presumably the CFI or the appropriate national court. By

contrast, an Article 18, decision requiring answers, even to facts concerning a

suspect undertaking’s general business activities, would be likely to be prohib-

ited by the rule in Saunders. The rule attacks legal compulsion not just to lead-

ing questions as in Orkem, but to a far broader swathe of questions. It is

submitted that applying Saunders in antitrust cases would be to prohibit the

asking of questions on such subjects as the operation of the business and

economic questions.83 Equally, if the Commission intends to back up the

power of interview contained in Article 19 by imposing heavy fines for

refusals by executives to attend an interview, Article 19 would fall foul of

Saunders. It is also difficult to see how the power to ask employees of a

suspect undertaking broad questions regarding the case envisaged in Article

20(2)(f) can be squared with Saunders, when failure to answer such questions

will again result in the imposition of heavy turnover fines.

It should be pointed out, however, that the existing powers under Articles

18, 19, and 20(2)(f) are not entirely devoid of substance in respect of their

power to obtain testimony evidence. They can be applied to third parties, such

as suppliers and customers, to obtain and supplement the Commission’s infor-

mation regarding a suspected antitrust infringement. Furthermore, the privi-

lege against self-incrimination does not affect the power of the Commission to

initiate on the spot inspections under Article 20.84 As Van Overbeek has

pointed out, the impact of the ECtHR case law may well encourage the

Commission to make more use of its inspection powers contained in Article

20.85 However, as argued below, the powers contained in Article 20 raise their

own problems when considered in the light of the ECHR case law.

C. The Power of Inspection, Article 20 and the Right to Home,

Private Life and Correspondence

Article 20(2) provides the Commission with the power to conduct inspections

83 Saunders, op cit, para 71. The ECtHR emphasised that even exculpatory or factual answers

given under compulsion could amount to an infringement of the privilege.

84 However, the power of the Commission to ask oral questions during inspections, under Art

14(1)(c), may well fall foul of Saunders in cases where fines can be imposed under Art 15(1)(c).

For a discussion of when fines can be imposed see Kerse, op cit, para 7.08. Should the White

Paper proposals be adopted in full the Commission will then have wide powers to ask questions

during inspections, and wide powers to impose fines for refusals or inadequate answers. White

Paper, op cit, para 113.

85 Van Overbeek, ‘The Right to Remain Silent in Competition Investigations: The Funke deci-

sion of the Court of Human Rights Makes Reform of the ECJ’s Case Law Necessary’ (1994)

ECLR 127, 132.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

72 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

of both business premises and means of transport, and in Article 20(2)(b) of

the ‘homes of directors, managers and other members of staff’ of the suspect

undertakings. The first ECHR issue here is whether Article 8(1), whose aim is

to protect private and family life, home, and correspondence against state

interference, applies to business premises. Consideration is then given to

whether interference by the Commission with the right set out in Article 8(1)

can be justified under Article 8(2). Finally, the proposed power in Article

20(2)(b) to permit the Commission to search private homes is examined in the

light of the ECHR case law.

It was unclear until relatively recently whether business premises could fall

within Article 8(1). However, in Niemietz v Germany the Court provided a

convincing argument as to why Article 8(1) should apply to business premises.

First, it pointed out that there was no reason of principle why the notion of

private life should be taken to exclude activities of a professional or business

nature, since after all it is in the course of their working lives that the majority

of people have a significant, if not the greatest opportunity, of developing rela-

tionships with the outside world.86 Secondly, it is often not possible to distin-

guish clearly which of an individual’s activities form part of his professional or

business life, and which do not. Furthermore, if Article 8 was interpreted as

only applying to those whose work and personal lives are not easily separated,

those whose work and personal lives are separable would not have the protec-

tion of Article 8. Such an interpretation, the Court argued, would lead to an

unacceptable inequality of treatment.87 Thirdly, in relation to the word ‘home’

Article 8 had already been interpreted in certain Contracting States, notably

Germany, as extending to business premises. Furthermore, it argued that such

an interpretation is fully consonant with the French text, since the word ‘domi-

cile’ has a broader connotation than the word ‘home’. Again, in relation to

‘home’ or ‘domicile’, the Court raised the equality of treatment question, as it

may be as equally impossible to distinguish between home and work premises

as between work and personal life.88 Fourthly, to interpret private life or home

as including professional or business activities or premises would be consonant

with the essential object and purpose of Article 8, namely to protect the indi-

vidual against arbitrary interference by the public authorities.89 Fifthly, the

Court also noted that the object of the search in Niemietz (and indeed most

searches in regulatory matters) was documentary evidence, including corre-

spondence. Unlike the use of the word ‘life’ in Article 8, no adjective is used

to qualify the word ‘correspondence’.90 Furthermore, as the Court pointed out,

in the context of correspondence in the form of telephone calls, no distinction

between private and business calls is made.91

The Court also observed that such an extensive interpretation would not

86[1993] 16 EHRR 97, para 29. 87 Niemietz, ibid, para 29.

88Ibid, para 30. 89 Ibid, para 31. 90 Ibid, para 32.

91 Ibid, para 32 and Huvig v France [1990] 12 EHRR 528, paras 8 and 25. See also Halford v

United Kingdom [1997] 25 EHRR 523.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 73

unduly hamper the Contracting States as they would retain their entitlement to

‘interfere’ to the extent permitted by Article 8(2). Furthermore, that entitle-

ment might be more far-reaching where professional or business activities or

premises were involved than would otherwise be the case.92

There are three parts to Article 8(2). First, any interference with Article

8(1) must be in accordance with the law. Secondly, any interference must have

a legitimate aim, and thirdly, such interference must be necessary in a demo-

cratic society. The Court has accepted that the Contracting States have a

margin of appreciation in assessing the need for supervision.93 However, the

Court also taken the view that the exceptions provided for in Article 8(2) are

to be interpreted narrowly, and the need for them in any given case must be

convincingly established.94

In respect of the first part, three requirements are placed on the authorities.

First, the interference must have some basis in the domestic legal order either

in statute or under the common law.95 Secondly, that law must be accessible,

meaning that it must be published.96 Thirdly, there is the core quality of the

law requirement: forseeability as to its consequences for the citizen, and

compatability with the rule of law.97 The forseeability criterion essentially

requires that the law must be sufficiently clear in its terms to give citizens an

adequate indication as to the circumstances in which the public authorities are

empowered to interfere with the rights protected under Article 8(1).98 The

scope of the rule of law criterion was set out by the Court in Malone v The

United Kingdom.99 It held that Article 8(1) implies that there must be a

measure of legal protection in domestic law against arbitrary interference by

public authorities.100

The second part imposes an obligation on the authorities that any interfer-

ence with Article 8 (1) must have a legitimate aim, such as national security,

public safety, the economic well-being of the country, the prevention of disor-

der or crime, the protection of health or morals, or the protection of the rights

and freedoms of others. Legitimate aims recognised by the Court and

Commission to permit searches include customs control,101 anti-terrorism

legislation,102 and the protection of copyright.103

In relation to third part, the ‘necessary in a democratic society’ criterion

the court has consistently focused upon the existence in the relevant legisla-

tion and practice of adequate and effective safeguards against abuse. The

Court’s view as to the adequacy of safeguards can be illustrated by three

92 Niemietz, para 31.

93 Funke, op cit, para 55.

94 Ibid, Klass v Germany [1979–1980] 2 EHRR 214, para 42.

95 Huvig, op cit, para 28.

96 Chappell v United Kingdom [1990] 12 EHRR 1, para 56, and Huvig, op cit, para 29.

97 Ibid, op cit, para 26. 98 Huvig, op cit, para 29.

99 [1985] 7 EHRR 14, para 33. 100 Huvig, op cit, para 33.

101 Funke, op cit.

102 John Murray v United Kingdom [1996] 22 EHRR 29. 103 Chappell, op cit.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

74 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

cases in relation to search and seizure operations approved or carried out by

the state. The first, Chappell v United Kingdom, concerned an Anton Pillar

order obtained in the English High Court. In that case a judicial warrant was

obtained ex parte; evidence was presented to the judge.104 The order itself

had significant limitations as to its scope: it could only be enforced at certain

times; it was only operational for a short period; and any materials seized

could only be used for specific purposes. Furthermore, these safeguards were

buttressed by a series of undertakings given by the plaintiffs or their solicitors.

Finally, the execution of the order was in the hands of a solicitor who,

although representing the plaintiff, had overriding obligations to comply with

the order as an officer of the court. Although the ECtHR agreed with the Court

of Appeal that the manner of entry and numbers involved was ‘ disturbing and

unfortunate and regrettable’ the safeguards were approved and the execution

of the order could be regarded as proportionate to the end pursued.105

By contrast, in Cremieux v France and Miahille v France the investigatory

powers of the French customs authorities were condemned. The Court noted

that:

the customs authorities had very wide powers, in particular, they had exclusive

competence to assess the expediency, number, length and scale of the inspection.

Above all in the absence of any requirement of a judicial warrant the restrictions

and conditions provided for in law which were emphasised by the government

appeared too lax and full of loopholes for the interference in the applicant right

to have been strictly proportionate to the legitimate aim pursued.106

However, it is clear that a judicial warrant is not required in every case where

the state wishes to enter premises, whether they be business or residential. In

Camenzind v Switzerland, despite the fact there was no judicial warrant, the

Court accepted that the interference was justified under Article 8(2). However,

in that case there were extensive safeguards, including notice, and the attendance

of a lawyer and an independent observer. Furthermore, the search was limited to

checking certain items of electrical equipment.107 It is therefore necessary to

examine carefully the circumstances of each case, in particular the extent of the

search, the means used, and the strength of the safeguards.

Any examination of the compliance of the Commission’s power of investi-

gation under Article 20 with Article 8 of the ECHR must be confined to

Article 20(4) decisions. This is because Article 20(3) authorisations to inves-

tigate permit an undertaking to refuse entry to the Commission with no risk of

a penalty being imposed as a consequence of its refusal to permit entry. Hence

there can be no interference with the rights of undertakings under Article 8(1),

and no need for justification under Article 8(2).

104 Ibid, op cit, paras 59 and 60.

105 Ibid, op cit, para 63.

106 Respectively, [1993] 16 EHRR 332, para 38 and [1993] 16 EHRR 357, para 40.

107 [1997] 28 EHRR 458, para 46.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Draft Competition Regulation 75

As powers such as those contained in Article 20(4) to examine and copy

documents on business premises by decision do fall within the scope of Article

8(1), it is necessary to consider whether those powers can be justified under

Article 8(2). As explained above there are three cumulative justifications that

have to be met: is the interference with Article 8(1) in accordance with the

law; does the interference have a legitimate aim; and is it necessary in a demo-

cratic society.

The first justification is itself in three parts that there be an actual basis in

domestic law, that the law is accessible, and that it is foreseeable and subject

to the rule of law. It is clear that the Commission’s powers of inspection have

a basis in the Community legal order. The power itself is set out in Article 20,

and further guidance is provided by decisions of the ECJ and CFI cases such

as AM&S, Hoechst and Hilti v Commission.108

The second question is whether the Commission’s power of inspection

complies with the Convention requirements as to accessibility. As Regulation

17 (and its successor), the case law and notices are and will be published, the

power of inspection can be said to comply with the accessibility criterion.

The forseeability criterion would appear to be complied with as a result of

the Commission’s modern practice of describing the procedural steps and the

use of its powers of inspection in its decisions.109 A more difficult question,

discussed under the ‘necessary in a democratic society head,’ is whether the

broad nature of the powers set out in the decision, unaccompanied by special

procedural safeguards, is justified by Article 8(2).

It is clear that Article 20 has a legitimate aim. The enforcement of the EC

competition regime aims to protect competition in the single market, and

thereby the economic well-being of the Community.

If the Article 20 powers are put alongside the English Anton Pillar regime,

which was approved by the ECtHR, and the French customs authorities

powers of search, which were condemned, the EC power at first sight looks as

if it falls on the condemned, French side of the line. Unlike the Anton Pillar

orders, there is no power of judicial warrant; like the French authorities the

Commission can act of its own volition and with broad discretion. That view

is reinforced by considering Camenzind, where no judicial warrant was

required by the ECtHR. However, in that case there was notice, the presence

of an independent observer, and the search itself was limited. By contrast the

Article 20 regime can operate without notice, without an independent

observer,110 and the power of investigation is very broad.

It can be argued that a number of additional safeguards are provided at

Community level to protect the rights of undertakings, by contrast with the

position under French customs law. First, it is only by decision and then

108T-30/89 [1991] ECR II 1439. 109 Kerse, op cit, para 3.21.

110Under Art 14(5) NCA officials may attend the investigation. They are not umpires or inde-

pendent observers. Art 14(5) makes it clear that the NCA officials are there to assist the

Commission. They may in fact take a direct part in the investigation. See Kerse, op cit, para 3.38.

https://doi.org/10.1093/iclq/51.1.55 Published online by Cambridge University Press

76 International and Comparative Law Quarterly

following opposition that enforcement powers are triggered. Secondly, if

opposed the Commission must seek assistance from the national authorities.

This may mean that a judicial warrant is required from the national courts, and

that it must be obtained according to provisions of national law. Finally, an

undertaking can challenge the Commission decision before the CFI.

However, it is open to question whether even these safeguards are suffi-

cient for the purposes of the third justification of Article 8(2). First, the

national systems may not, as in the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Italy, and

Austria, require any judicial warrant prior to national enforcement of an

Article 20(4) decision.111 Furthermore, judicial review by the national courts

is strictly limited by Article 20(8). Following the ruling in Hoechst Article

20(8) limits the national court review to ‘establishing that the Commission

decision is authentic and that the enforcement measures envisaged are neither

arbitrary nor excessive’. Paragraph 8 then goes on to expressly rule out

national court review of either the necessity of the inspection or orders requir-

ing the Commission to adduce more evidence to the court.

At first sight Article 20(8) does offer undertakings a basis to challenge an

Article 20(4) decision by providing that the lawfulness of a Commission deci-

sion shall be subject to review by the Court of Justice.112 It is possible to inter-

pret this sentence as providing the basis for effective judicial control over

Article 20(4) decisions. However, Article 20(8) does not provide for substan-

tial pre-inspection control, for example, as occurred in Chappell in respect of

an Anton Pillar order. Furthermore, it does not alter the existing case law that

such challenges do not have suspensory effect. An undertaking can seek a

suspension of a decision until final judgment. However, in order to obtain such

a suspension it would have to make an application to the CFI under Article 242

of the EC Treaty. That article requires a plaintiff to provide proof of serious

and irreparable damage that would occur if the suspension were not granted.

It is difficult to see how any undertaking would be able to provide proof of

serious and irreparable damage simply by permitting entry to Commission

inspectors. Furthermore, as Kerse points out, it is doubtful as a practical

matter, whether, in the circumstances of an unannounced inspection, a chal-

lenge under Article 230, together with an application for suspension, could be

effected in time to prevent the inspection decision being implemented.113

In addition to an effective judicial safeguard, the case law of the ECtHR,

especially the judgment of the Court in Chappell, suggests that it will seek a

number of other significant limitations upon the powers of the Commission. In