Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Yehoshua_Frenkel_Review_of_Political_Tho

Yehoshua_Frenkel_Review_of_Political_Tho

Uploaded by

SaidaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Yehoshua_Frenkel_Review_of_Political_Tho

Yehoshua_Frenkel_Review_of_Political_Tho

Uploaded by

SaidaCopyright:

Available Formats

MAMLŪK STUDIES REVIEW Vol.

25, 2022 225

Mohamad El-Merheb, Political Thought in the Mamluk Period: The Unnecessary Ca-

liphate (Edinburgh, 2022). Pp. vii, 216.

Reviewed by Yehoshua Frenkel, University of Haifa

El-Merheb’s work revolves around five compilations by Mamluk authors: Ibn

Jamāʿah, al-Qarafī, al-Subkī, Ibn Ṭalḥah, and an anonymous Sufi author. He

opens with a critical review of past scholarship on the “Constitutional Orga-

nization of Islam” (Gibb): a popular historical theoretical frame that he tags a

longue durée view of Islamic political jurisdiction, which is actually an essen-

tialist and unhistorical approach. As early as the tenth century, Muslim jurists

were aware that the utopian ideal of a united Muslim ummah was unrealistic. Al-

Ashʿarī opens his heresiography with the historical evaluation “the first thing

that divided the Muslims was their disagreement regarding the community’s

leadership (imāmah)”. 1

Chapter 1, “Reading Islamic Political Thought,” provides a critical review

of studies on the institution of the caliphate. To illuminate the deficiency of

the research, El-Merheb opens with a fresh view, drawn by a comparison of the

fourteenth-century European political theory of Marsilius of Padua with the

study of Islamic constitutional writings of Ibn Jamāʿah. He criticizes the legal

lineage that several Western scholars have (incorrectly) reconstructed. At this

juncture he highlights, inter alia, the important place that should be assigned

to al-Jūwaynī (419–78/1028–85). Based upon his reading of the primary sources,

El-Merheb disagrees with the interpretation of the caliphate’s history advocated

by Mona Hassan and disapproves of studies about the post-1258 Islamic political

theory by Ann Lambton, in particular.

El-Merheb turns next to a Persian “mirror for princes” attributed to al-

Ghazālī. I believe that we should differentiate between this text and the Ara-

bic title that is accredited to the great scholar. This pseudo-Ghazālī circulated

among Mamluk readers, who did not question its authenticity. Summarizing

the state of the art, El-Merheb argues that the prevailing longue durée research

method into the basic principles and law of the “Islamic state” has resulted in

limited success. In its place, he offers a contextualizing interpretation of the

political thinkers, drawn against the background of their distinctive intellec-

tual and empirical worlds, their social, cultural, and political contexts. Such a

historian identifies the political language of the texts he investigates. A survey

of the Ashrafīyah Library serves to parse this working method. This institution

illuminates the importance of the governing military elite in the educational

1

Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī al-Ashʿarī, Maqālāt al-Islāmīyīn, ed. Hellmut Ritter (Wiesbaden, 1400/1980), 2

(ll. 3–4).

©2022 by Yehoshua Frenkel.

DOI: 10.6082/35ht-df95. (https://doi.org/10.6082/35ht-df95)

DOI of Vol. XXV: 10.6082/msr25. See https://doi.org/10.6082/msr2022 to download the full volume or individual

articles. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY). See

http://mamluk.uchicago.edu/msr.html for more information about copyright and open access.

226 Book Reviews

and religious spheres. The religious establishment relied on the patronage of

military officers. The complier of the Arabic pseudo-Ghazālī articulated his

constitutional theory under the shade of their canopy.

Chapter 2 deals with Ibn Jamāʿah, a Shafiʿi jurist whose theory of rulership,

legitimacy, and power attracted scholarly attention as early as 1868. 2 Resem-

bling al-Subkī, Ibn Jamāʿah was an observer-participant, a man of the pen who

occupied legal-administrative positions. El-Merheb analyses Drafting Ordinanc-

es towards Running the Affairs of the People of Islam, certainly Ibn Jamāʿah’s best

known work. Highlighting the originality of this compilation, he examines it

as a political and constitutional text (tadbīr), as well as an administrative guide

(taḥrīr), while taking into consideration the compiler’s political position.

Although the term tadbīr itself is not used in the Quran, the present tense

of its verbal form yudabbiru is repeated four times: Sūrat Yūnus (10:3 and 31);

Sūrat al-Raʿd (13:2); and Sūrat al-Sajadah (32:5). In these verses, the Quran in-

forms the believers that the Lord created the Heavens and he directs the affair

(yudabbiru al-amra). Dabbara amran signifies “he executed an affair with consid-

eration.” Dabbara al-bilāda means “he conducted the affairs of the country.” This

meaning of the root ⱱd.b.r. (to guide, to lead) can be traced in Hebrew, Aramaic,

and Syriac. It resembles the Greek oikonomia (management of the house). 3 In the

Middle Islamic Period, books entitled tadbīr dealt with politics, economy, and

ethics (akhlāq). 4 It has been claimed that the earliest title on these topics is Sulūk

al-mālik, a book attributed to Aḥmad Ibn Abī al-Rabīʿ (presumably died 227/842).

Yet, this early date should be rejected. Jirjī Zaydān suggests the early Mamluk

period, a date that indeed seems more plausible. 5

El-Merheb turns next to examine the jihad manuals composed by Ibn Jamāʿah.

Also cataloged as furūsīyah and military guides, these two short booklets are closely

related to the compiler’s political world view and his administrative duties. In line

with the Islamic “mirror for princes,” these works display the importance of just

government. El-Merheb here offers fresh insight into the study of middle Islamic-

period political writings. This is followed with critical remarks on past scholarly

studies of Ibn Jamāʿah’s taḥrīr/tadbīr. According to El-Merheb’s interpretation, Ibn

2

Alfred von Kremer, Geschichte der herrschenden Ideen des Islams: der Gottesbegriff, die Prophetie und

Staatsidee (Leipzig, 1868), 416.

3

W. Heffening, “Tadbīr,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed.

4

Hellmut Ritter, “Ein Arabisches Handbuch der Handelswissenschaft” (Phil. Diss., Bonn, 1914);

Claude Cahen, “A propos et autour d’‘Ein arabisches Handbuch der Handelswissenschaft,’”

Oriens 15 (1962): 168.

5

Frédéric Bauden and Antonella Ghersetti, “L’Art de servir son monarque: Le Kitāb Waṣāyā

Aflāṭūn al-ḥakīm fī ḫidmat al-mulūk, édition critique et traduction précédées d’une introduc-

tion,” Arabica 54, no. 3 (2007): 298.

©2022 by Yehoshua Frenkel.

DOI: 10.6082/35ht-df95. (https://doi.org/10.6082/35ht-df95)

DOI of Vol. XXV: 10.6082/msr25. See https://doi.org/10.6082/msr2022 to download the full volume or individual

articles. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY). See

http://mamluk.uchicago.edu/msr.html for more information about copyright and open access.

MAMLŪK STUDIES REVIEW Vol. 25, 2022 227

Jamāʿah legitimates the coercive imamate. Being a Qurayshite is not a prerequisite

qualification for one who aspires to hold the position of sultan. He then surveys

Shāfiʿ ibn ʿAlī’s History (Bibliothèque Nationale MS Arabe 839).

Chapter 3 is based on deep investigation of two manuscripts that articulate

a Sufi position on political power and authority: (1) Tāj al-Dīn Ibn Ḥamawīyah’s

Al-Siyāsah al-mulūkīyah and (2) the anonymous (not al-Khiḍr) Miṣbāḥ al-hidāyah fī

ṭarīq al-imāmah, a treatise that represents an early attempt to set down a juristic

interpretation in the light of Baybars’ successful Abbasid restoration. 6 The au-

thor examines the close relations between the ruling military aristocracy and

al-ṣūfīyah. Their play in the political arena is narrated in contemporary chroni-

cles. The Miṣbāḥ is a Sufi political treatise that validates the rule of a non-Quray-

shite imam. Its anonymous author departs from earlier Sunni political theory,

a turn that can be identified in writings of Muslim scholars who lived under the

early Saljuqs. Moreover, it is an additional example of the reception of Persian

scholarly works in Ayyubid and Mamluk Syria and Egypt.

Chapter 4 concentrates on two jurists, Kamāl al-Dīn Ibn Ṭalḥah al-Wazīr

al-Nuṣaybī al-Shāfiʿī (582–652/1186–1254) 7 and Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad Qarāfī

al-Mālikī (626–84/1228–85). Their literary production is, according to El-Mer-

heb, representative or archetypical of Sunni constitutional jurisdiction in

thirteenth-century Syria and Egypt. He provides a condensed account of these

works and their political-administrative contexts. While analyzing Ibn Ṭalḥah’s

text, he refers to other works in this genre, highlighting their place in the gene-

alogy of advice-to-the-ruler literature, although he refrains from cataloguing

this book as belonging to the Fürstenspiegel library.

Recent years have seen a growing interest in Mamluk historical narratology.

Chapter 5 dwells upon this topic. This is in line with the author’s working the-

sis that the “Political thought of the Mamluk period should be studied in con-

junction with the historical writing.” The first case study examines al-Subkī’s

biography of Ibn ʿAbd al-Salām, who is portrayed in the Mamluk sources as an

exemplary model. These texts are used to emphasize the methodology of con-

textualism. Reading a political text requires the reader’s acquaintanceship with

the historiography and with the prevailing conventions that governed the po-

litical discourse of the time. The author outlines Shafiʿi political thought. 8 This

6

Mustafa Banister, The Abbasid Caliphate of Cairo (1261–1517): Out of the Shadows (Edinburgh, 2021),

231–32.

7

For his contribution to occultism see “Al-Durr al-munaẓẓam fī al-sirr (al-ism) al-aʿẓam,” Na-

tional Library of Israel MSS Yahuda 471 (fol. 367) and 482.

8

Cf. Michael Winter, “Inter-madhhab competition in Mamluk Damascus: al-Tarsusi’s counsel

for the Turkish Sultans,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 25 (David Ayalon Memorial Volume

2001): 195–211.

©2022 by Yehoshua Frenkel.

DOI: 10.6082/35ht-df95. (https://doi.org/10.6082/35ht-df95)

DOI of Vol. XXV: 10.6082/msr25. See https://doi.org/10.6082/msr2022 to download the full volume or individual

articles. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY). See

http://mamluk.uchicago.edu/msr.html for more information about copyright and open access.

228 Book Reviews

is followed by a concise study of al-Subkī’s The Restorer of Favors, which is charac-

terized as “a source of political thought that clearly upholds Shāfiʿī’s constitu-

tional concerns for the rule of law and limited government.”

Mohamad El-Merheb’s book opens a new path in the study of Islamic consti-

tutional theory. By adding new genres he enlarges the data sources that histo-

rians of Sunni political thought may draw upon. He provides fresh analysis and

calls out commonly accepted paradigms, such as Lambton’s and Crone’s well-

received interpretations of Islamic government.

©2022 by Yehoshua Frenkel.

DOI: 10.6082/35ht-df95. (https://doi.org/10.6082/35ht-df95)

DOI of Vol. XXV: 10.6082/msr25. See https://doi.org/10.6082/msr2022 to download the full volume or individual

articles. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY). See

http://mamluk.uchicago.edu/msr.html for more information about copyright and open access.

You might also like

- Parable and Politics in Early Islamic History: The Rashidun CaliphsFrom EverandParable and Politics in Early Islamic History: The Rashidun CaliphsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 'Abdallāh Al-Samāhijī's "Munyat Al-MumārisīnDocument30 pages'Abdallāh Al-Samāhijī's "Munyat Al-Mumārisīnba7raini100% (1)

- Hasan-I-Sabbah: His Life and ThoughtFrom EverandHasan-I-Sabbah: His Life and ThoughtRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ambush Alley - Force On Force - Enduring Freedom PDFDocument177 pagesAmbush Alley - Force On Force - Enduring Freedom PDFSven Escauriza100% (7)

- Schools of Muslim LawDocument13 pagesSchools of Muslim LawKarthiayani A.No ratings yet

- Ship Breakers Association PDFDocument16 pagesShip Breakers Association PDFMigration Solution67% (3)

- Ibn Khaldun Between Arab Nationalism & Ottoman CalDocument10 pagesIbn Khaldun Between Arab Nationalism & Ottoman CalFauzan RasipNo ratings yet

- (9789004169531 - Guardians of Faith in Modern Times - Ulama in The Middle East) Chapter Two. Al-Jabarti's Attitude Towards The Ulama of His TimeDocument17 pages(9789004169531 - Guardians of Faith in Modern Times - Ulama in The Middle East) Chapter Two. Al-Jabarti's Attitude Towards The Ulama of His TimeMohamed SalahNo ratings yet

- Work and Leisure in Islamic Debate About Work - The Kitab Al-Kasb As A Case StudyDocument10 pagesWork and Leisure in Islamic Debate About Work - The Kitab Al-Kasb As A Case Studygumel99No ratings yet

- Between Metaphor and Context: The Nature of The Fatimid Ismaili Discourse On Justice and InjusticeDocument7 pagesBetween Metaphor and Context: The Nature of The Fatimid Ismaili Discourse On Justice and InjusticeShahid.Khan1982No ratings yet

- Confronting The CaliphDocument30 pagesConfronting The CaliphshiraaazNo ratings yet

- MSR VII-2 2003-Broadbridge pp231-245Document15 pagesMSR VII-2 2003-Broadbridge pp231-245hilma fanniar rNo ratings yet

- Did Salah Al Din Destroy The Fatimids BooksDocument19 pagesDid Salah Al Din Destroy The Fatimids BooksHusain NajmiNo ratings yet

- 352-Article Text-535-657-10-20130203Document4 pages352-Article Text-535-657-10-20130203Muzafar SoomroNo ratings yet

- Faisal Chaudhry - Public Violence in Islamic Societies - Power, Discipline and the Construction of the Public Sphere, 7th–19th Centuries [International Journal of Asian Studies vol. 10 iss. 2]Document3 pagesFaisal Chaudhry - Public Violence in Islamic Societies - Power, Discipline and the Construction of the Public Sphere, 7th–19th Centuries [International Journal of Asian Studies vol. 10 iss. 2]rafastollNo ratings yet

- Importance of The Tarikh Tradition in ReDocument8 pagesImportance of The Tarikh Tradition in Renishant1210sharmaNo ratings yet

- Governanceinmuslimperiod16 26,32 43 PDFDocument74 pagesGovernanceinmuslimperiod16 26,32 43 PDFami seipritamNo ratings yet

- Reading9Document3 pagesReading9Harsh RajputNo ratings yet

- Between Revolution and State Fatimide StateDocument7 pagesBetween Revolution and State Fatimide StateMoufasMparoufasNo ratings yet

- Politics and Society in Medieval India - Habib (Vol 2)Document236 pagesPolitics and Society in Medieval India - Habib (Vol 2)Ahsan 11100% (2)

- Tarikh I Feroz ShahiDocument67 pagesTarikh I Feroz ShahiAbhishek Jain100% (3)

- Anti-Feudal Elements in Classical Malay Political TheoryDocument12 pagesAnti-Feudal Elements in Classical Malay Political TheoryPrincess Hannah MapaNo ratings yet

- 67072-Article Text-80958-1-10-20171119 PDFDocument6 pages67072-Article Text-80958-1-10-20171119 PDFEshal MalikNo ratings yet

- Islamic Legal Thought: A Compendium of Muslim JuristsDocument5 pagesIslamic Legal Thought: A Compendium of Muslim JuristsShabab ASHNo ratings yet

- Sean Anthonyfreewillin ISLAMDocument15 pagesSean Anthonyfreewillin ISLAMIsauro YosaNo ratings yet

- Haarmann The Library of A Jerusalem ScholarDocument8 pagesHaarmann The Library of A Jerusalem ScholarVIRGINIA VÁZQUEZ HERNÁNDEZNo ratings yet

- A Study of Sources of The Sultanate With Emphasis On The Malfuzat and The Premakhyan TraditionDocument8 pagesA Study of Sources of The Sultanate With Emphasis On The Malfuzat and The Premakhyan TraditionIt's vibpathak100% (1)

- Eido Issam A Critical Edition of Umdat ADocument4 pagesEido Issam A Critical Edition of Umdat ABall SOhardNo ratings yet

- Analyzing A Tool of Is Propaganda Ibn ADocument16 pagesAnalyzing A Tool of Is Propaganda Ibn Abidor43362No ratings yet

- 02 AbstractDocument7 pages02 AbstractRashaNo ratings yet

- Concept of Shūra in Fazlur RahDocument18 pagesConcept of Shūra in Fazlur Rahhusam almallakNo ratings yet

- Umar'S Assurance of Aman To The People of Aelia (Bayt Al-Maqdis - Islamicjerusalem) : A Critical Analytical Study of Al-Tabari'S VersionDocument16 pagesUmar'S Assurance of Aman To The People of Aelia (Bayt Al-Maqdis - Islamicjerusalem) : A Critical Analytical Study of Al-Tabari'S VersionAnonymous dUVCB7mNo ratings yet

- 84-329-1-PB Rethinking Diplomacy and IslamDocument4 pages84-329-1-PB Rethinking Diplomacy and Islamkestar09No ratings yet

- Longing For The Lost Caliphate: A Transregional History: 95 Book ReviewsDocument4 pagesLonging For The Lost Caliphate: A Transregional History: 95 Book ReviewsArman FirmanNo ratings yet

- Siddiqui - Book ReviewDocument6 pagesSiddiqui - Book Reviewtushar vermaNo ratings yet

- Historians of EgyptDocument4 pagesHistorians of EgyptArastu AzadNo ratings yet

- aISHA AND THE ROLE OF WOMENDocument7 pagesaISHA AND THE ROLE OF WOMENNikita KohliNo ratings yet

- Vibhuti PathakDocument8 pagesVibhuti PathakIt's vibpathakNo ratings yet

- Tayeb El-Hibri Reinterpreting Islamic Historiography - Harun Al-Rashid and The Narrative of The Abbasid Caliphate (Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization) 1999Document248 pagesTayeb El-Hibri Reinterpreting Islamic Historiography - Harun Al-Rashid and The Narrative of The Abbasid Caliphate (Cambridge Studies in Islamic Civilization) 1999Mădălina Georgiana Andonie100% (1)

- Yousefi IslamwithoutFuqaha OnlineDocument37 pagesYousefi IslamwithoutFuqaha OnlineCafer NalNo ratings yet

- Hazm BiogDocument3 pagesHazm BiogmuhammaddoyokarifinNo ratings yet

- Imam Al-Awzai and His Humanitarian Ideas (707-774)Document9 pagesImam Al-Awzai and His Humanitarian Ideas (707-774)Shabab ASHNo ratings yet

- Mattson, Ingrid Review of Rebellion and Violence in Islamic Law by Khaled Abou El FadlDocument5 pagesMattson, Ingrid Review of Rebellion and Violence in Islamic Law by Khaled Abou El FadlcoldplaylionNo ratings yet

- Futuh Al-BuldanDocument32 pagesFutuh Al-BuldanImam Kasep TeaNo ratings yet

- MSR XX 2017 GardinerDocument36 pagesMSR XX 2017 GardinerDaniel RizviNo ratings yet

- The Islamic School of Law Evolution, Devolution, and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters, Frank Vogel - Muhammad Qasim Zaman PDFDocument7 pagesThe Islamic School of Law Evolution, Devolution, and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters, Frank Vogel - Muhammad Qasim Zaman PDFAhmed Abdul GhaniNo ratings yet

- Reading The Emergence of Islamic StateDocument5 pagesReading The Emergence of Islamic StateMinas MonirNo ratings yet

- Fatwa in Europe and Muslim WorldDocument26 pagesFatwa in Europe and Muslim Worldsublimity2010No ratings yet

- اختلاف اخباریون و اصولیون شیعهDocument31 pagesاختلاف اخباریون و اصولیون شیعهhamaidataeiNo ratings yet

- The Intersection Between Sufism and PoweDocument9 pagesThe Intersection Between Sufism and PoweSamita RoyNo ratings yet

- Cannibalism - (In Safavid Dynasty, Part of Iran's History With Analysis)Document23 pagesCannibalism - (In Safavid Dynasty, Part of Iran's History With Analysis)Farshad FouladiNo ratings yet

- How Hanafism Came To Originate in KufaDocument30 pagesHow Hanafism Came To Originate in Kufaask1984No ratings yet

- Caliphate and Political Jurisprudence in IslamDocument20 pagesCaliphate and Political Jurisprudence in IslamIqbal bin YusufNo ratings yet

- Frolov - Notes On The Composition of David Al-Muqammis's Twenty Chapters PDFDocument14 pagesFrolov - Notes On The Composition of David Al-Muqammis's Twenty Chapters PDFrathkiraniNo ratings yet

- PESHAWAR NIGHTS Part - 1 - Sultanul-Waizin Shirazi - XKPDocument502 pagesPESHAWAR NIGHTS Part - 1 - Sultanul-Waizin Shirazi - XKPIslamicMobilityNo ratings yet

- The Collection and Edition of Ibn TaymiDocument21 pagesThe Collection and Edition of Ibn TaymiRodrigoAdemNo ratings yet

- Ibn-e-Khaldoon: 1. Kitab-al-Ibrar ..It Is A Universal History Written in Seven Volumes, The Introduction ToDocument28 pagesIbn-e-Khaldoon: 1. Kitab-al-Ibrar ..It Is A Universal History Written in Seven Volumes, The Introduction ToPalwasha KhanNo ratings yet

- The Medieval History Journal Volume 9 Issue 2 2006 (Doi 10.1177/097194580600900206) Sarkar, N. - 'The Voice of Mahmud' - The Hero in Ziya Barani's Fatawa-I JahandariDocument30 pagesThe Medieval History Journal Volume 9 Issue 2 2006 (Doi 10.1177/097194580600900206) Sarkar, N. - 'The Voice of Mahmud' - The Hero in Ziya Barani's Fatawa-I JahandariSabah Mushtaq100% (1)

- Astrology Lettrism Geomancy The Occult-SDocument9 pagesAstrology Lettrism Geomancy The Occult-SSandeep BadoniNo ratings yet

- Did Ṣalāḥ Al-Dīn Destroy The Fatimids' Books - An Historiographical Enquiry - REVISEDDocument36 pagesDid Ṣalāḥ Al-Dīn Destroy The Fatimids' Books - An Historiographical Enquiry - REVISED8 klimatNo ratings yet

- Legal in MedievalDocument196 pagesLegal in MedievalHabib ManzerNo ratings yet

- Glossar Zu Kinderib (Anatolisches Arabisch)Document3 pagesGlossar Zu Kinderib (Anatolisches Arabisch)Ömer AcarNo ratings yet

- The Conclusive Argument From God Shah Wa PDFDocument5 pagesThe Conclusive Argument From God Shah Wa PDFഒരു യാത്രക്കാരൻNo ratings yet

- S Israk Mikraj Solat 17.02.2023 EnglishDocument60 pagesS Israk Mikraj Solat 17.02.2023 EnglishemaskhayraNo ratings yet

- Father AbrahamDocument4 pagesFather AbrahamChristian Lemuel Tangunan TanNo ratings yet

- Tipu Sultan Was Also Known AsDocument6 pagesTipu Sultan Was Also Known AsIrfan AliNo ratings yet

- Islam in Plural Society FinalDocument2 pagesIslam in Plural Society Finalhaha kelakarNo ratings yet

- PPDB SMP Bp-Margasari-2022Document34 pagesPPDB SMP Bp-Margasari-2022Akhmad JaelaniNo ratings yet

- The Holy Quran in ItalianDocument199 pagesThe Holy Quran in Italianweird johnNo ratings yet

- Historical Information About The First Hospital in SamarkandDocument3 pagesHistorical Information About The First Hospital in SamarkandEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Hajj Brochure 1432Document2 pagesHajj Brochure 1432Md FrhmNo ratings yet

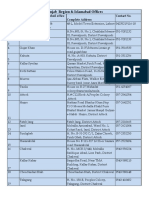

- Tehsil OfficesDocument22 pagesTehsil OfficesWaqarali ShahNo ratings yet

- Cash Waqf Empower SME TohirinDocument15 pagesCash Waqf Empower SME TohirinRahma NiezNo ratings yet

- Pipfa Pakistan Result Summer2019Document32 pagesPipfa Pakistan Result Summer2019Khobaib AliNo ratings yet

- Commentry of Ibn Taymiyyah On Futuh Al GaybDocument16 pagesCommentry of Ibn Taymiyyah On Futuh Al GaybTaymiNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Acara Pengarahan Unit Konseling FK UlmDocument5 pagesJadwal Acara Pengarahan Unit Konseling FK UlmTias FirdayantiNo ratings yet

- Shri Ram Janam Bhoomi Ayodhya Verdict Part 9 of 14Document500 pagesShri Ram Janam Bhoomi Ayodhya Verdict Part 9 of 14satyabhashnamNo ratings yet

- Ramli Field ReportDocument13 pagesRamli Field ReportMubashirKhattakNo ratings yet

- The Kite Runner Study GuideDocument43 pagesThe Kite Runner Study Guidetheology282% (11)

- Shaykh Mokhtar Adhkar BookletDocument59 pagesShaykh Mokhtar Adhkar BookletKhadijah Qamar100% (1)

- Chapter 5 ASSESSMENTDocument7 pagesChapter 5 ASSESSMENTNarte, Angelo C.No ratings yet

- Memogate - Detailed OrderDocument88 pagesMemogate - Detailed Ordermfarhanonline1181No ratings yet

- Nilai Uh Bab 1 KLS X Il 2-1Document2 pagesNilai Uh Bab 1 KLS X Il 2-1Putra EkaNo ratings yet

- Engineering Program Selected Candidate ListDocument23 pagesEngineering Program Selected Candidate ListbrokenheartNo ratings yet

- Who Wrote The Qur'an?: X. QiblasDocument20 pagesWho Wrote The Qur'an?: X. QiblasUNCLBEENNo ratings yet

- Peserta E&KEE 2018Document8 pagesPeserta E&KEE 2018Auphi OktaNo ratings yet

- The Sahabah's Attitude Towards Innovations: by Al-Jumu'ah MagazineDocument3 pagesThe Sahabah's Attitude Towards Innovations: by Al-Jumu'ah MagazineUmarRR11No ratings yet

- Friday KhutbahDocument2 pagesFriday KhutbahOlabanji Shonibare100% (1)

- Arabic With Husna (Lesson 5) Unit 1 (1.3) Bayyinah TV Transcript NotesDocument10 pagesArabic With Husna (Lesson 5) Unit 1 (1.3) Bayyinah TV Transcript NotesMUSARRAT BANO100% (6)

- Makalah Malik BennabiDocument5 pagesMakalah Malik BennabiHilman Fikri AzmanNo ratings yet

![Faisal Chaudhry - Public Violence in Islamic Societies - Power, Discipline and the Construction of the Public Sphere, 7th–19th Centuries [International Journal of Asian Studies vol. 10 iss. 2]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/748483109/149x198/75d5bad866/1720325665?v=1)