Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Under 5 - Copy

Under 5 - Copy

Uploaded by

Anika AhmedCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Under 5 - Copy

Under 5 - Copy

Uploaded by

Anika AhmedCopyright:

Available Formats

Cultures and Selves: A Cycle of Mutual Constitution

Author(s): Hazel Rose Markus and Shinobu Kitayama

Source: Perspectives on Psychological Science , JULY 2010, Vol. 5, No. 4 (JULY 2010), pp.

420-430

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of Association for Psychological Science

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41613449

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41613449?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Inc. and Association for Psychological Science are collaborating with JSTOR

to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives on Psychological Science

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

aps ЯШШЁШЁШШ I association for

ЯШШЁШЁШШ I association for

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE

Perspectives on Psychological Science

5(4) 420-430

Cultures and Selves: A Cycle of Mutual © The Author(s) 2010

Reprints and permission:

Constitution sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 1 0.1 177/1745691610375557

http://pps.sagepub.com

®SAGE

Hazel Rose Markus1 and Shinobu Kitayama2

'Department of Psychology, Stanford University, CA and department of Psychology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Abstract

The study of culture and self casts psychology's understanding of the self, identity, or agency as central to the ana

interpretation of behavior and demonstrates that cultures and selves define and build upon each other in an ongoing

mutual constitution. In a selective review of theoretical and empirical work, we define self and what the self does, d

culture and how it constitutes the self (and vice versa), define independence and interdependence and determine how

shape psychological functioning, and examine the continuing challenges and controversies in the study of culture an

propose that a self is the "me" at the center of experience - a continually developing sense of awareness and ag

guides actions and takes shape as the individual, both brain and body, becomes attuned to various environmen

incorporate the patterning of their various environments and thus confer particular and culture-specific form and fun

the psychological processes they organize (e.g., attention, perception, cognition, emotion, motivation, interpersonal rela

group). In turn, as selves engage with their sociocultural contexts, they reinforce and sometimes change the ideas, prac

institutions of these environments.

Keywords

culture, self, agency, independence, interdependence

Within psychology, the empirical study of the self asina the

cul-U.S., but by judgments made about both the self and

tural product and process is now almost three decades aboutold

one's mother in China (Zhu, Zhang, Fan, & Han, 2007).

(e.g., A. Fiske, Kitayama, Markus, & Nisbett, 1998; MarkusMoreover, in the last decade, the cultural comparisons stud-

& Kitayama, 1991; Shweder & Bourne, 1984; Triandis, ied are no longer just between people in North American and

1989). Hundreds of surveys, laboratory experiments, andEast Asian contexts; they now include comparisons across a

field

studies have bolstered earlier theories and ethnographic obser-of other significant social distinctions. Researchers also

variety

vations, drawing attention to powerful variation in self andfor example, that people in West African settings claim

know,

personhood. Researchers now have a good grasp of more why enemies

the and fewer friends than those in North American

nail that sticks out is likely to be hammered down insettings

Japan (Adams, 2005); that Western Europeans are less likely

whereas the squeaky wheel attracts grease and attentionthan North Americans to associate happiness with personal

in the

United States (for reviews, see Heine, 2008; Kitayama &

achievement (Kitayama, Park, Sevincer, Karasawa, & Uskul,

Cohen, 2007). They know, for example, that North American

2009); that Latino dyads talk, smile, and laugh more than do

Black

students can be expected to speak up in class more than and White dyads (Holloway, Waldrip, & Ickes, 2009);

their

Korean American counterparts (Kim, 2002); that parental

that Protestants are more likely than Jews to believe that people

expectations can have opposite motivational effects inhave

Asiancontrol over their thoughts (A.B. Cohen & Rozin, 2001);

American and European American families (Iyengar & Lep-

that people from the U.S. South respond with more anger to

per, 1999); that Japanese Olympic gold medalists, in compar-

insults than do Northerners (Nisbett, 1993); and that working

ison with American medalists, likely discuss their failures and

faults more than their successes and virtues (Markus, Uchida,

Omoregie, Townsend, & Kitayama, 2006); that helping others

is a moral obligation that holds whether or not one likes the

Corresponding Author

person in Indian contexts, but not in American contexts

Hazel Rose Markus, Department of Psychology, Jordan Hall, Building 420,

(Miller & Bersoff, 1998); and that the medial prefrontal cor- University, Stanford,

Stanford CA 94305

tex of the brain is activated by judgments made about E-mail:

the self

hmarkus@stanford.edu

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Culture and Self 42 1

class Americans react less strongly than middle-class Ameri- current and fu

cans to having their choices denied (Snibbe & Markus, 2005). & Scheier, 1998

These striking differences in behavior, as well as hundredssituated and, a

of others like them, are important in their own right. They texts in signifi

markedly expand the range of the normal, or of the "good" Just as one ca

or "right way to be," by revealing patterns of thinking, feeling, cannot be a sel

and acting that have not been part of mainstream psychology. lically mediat

Understanding these differences has significant practical appli-the social env

cations for intergroup relations, education, health, well-being, Markus & Kita

business, and peaceful coexistence in an increasingly diverse or constitution

and interconnected world. The study of culture and self, how-"how" and "when." Cultural variation across selves arises

ever, has two other highly significant consequences for the from differences in the images, ideas (including beliefs, values,

field of psychology, and they are the focus here. and stereotypes), norms, tasks, practices, and social interac-

tions that characterize various social environments and reflects

First, the study of culture and self has renewed and extended

psychology's understanding of the self, identity, or agency differences

and in how to attune to these environments.

casts it as central to the analysis and interpretation of behavior.

Theorists use a family of overlapping terms for the nexus of

Experience is socioculturally patterned, and the self reflects the

the biological, psychological, and sociocultural: self, self-

individual's engagement with the world that is the source concept,

of self-schema, self-construal, selfway, self-narrative,

this patterning: The array of contrasting behavioral differences

ego, psyche, mind, identity, personal identity, social identity,

and agency. Agency is the most general or global term and

described in the opening paragraph can all be illuminated with

a focus on what it means to be a self or agent in a particular

refers to acting in the world. Self is usually interchangeable

sociocultural context. with agency but is sometimes used to refer more specifically

Second, the study of culture and self has led to the realiza-

to how the person thinks or believes him or herself to be. Iden-

tity is typically used when the emphasis is on how others, be

tion that people and their sociocultural worlds are not separate

they individuals or groups, influence the person. All of the

from one another. Instead they require each other and complete

terms are similar in purpose. They attempt to index the

one another. In an ongoing cycle of mutual constitution, people

dynamic and recursive process of organizing and integrating

are socioculturally shaped shapers of their environments; they

make each other up and are most productively analyzed through which the individual, the biological entity, becomes

together (Shweder, 2003). The comparative method of socio-a meaningful entity - that is, a person.

cultural psychology reveals that although feeling, thinking, and

acting can take particular, culture-specific forms, the capacity

What Does a Self Do?

to continually shape and to be shaped by the context is a pow-

erful human universal. Selves are implicitly and explicitly at work in all aspects o

In the sections below, we examine these two consequencesbehavior: attention, perception, cognition, emotion, motivat

relationships, and group processes. More specifically, o

of the study of culture and self in detail. In the course of a selec-

ongoing sense of self functions as a foundational schema t

tive review of some of the major empirical and theoretical con-

tributions, we will define self and what the self does, define

recruits and organizes more specific self-regulatory schém

culture and how it constitutes the self (and vice versa), define

including cognitive, emotional, motivational, somatic, and b

independence and interdependence and determine how they vioral schémas. Some of the compelling evidence for selve

shape psychological functioning, and examine the continuing work can be seen in studies in U.S. contexts with American

challenges and controversies in the study of culture and self.ticipants. People hear their own name across a noisy crow

room (Wood & Cowan, 1 995), remember their own contribut

to a project better than they remember the contributions

What Is a Self?

their coworkers (Ross & Sicoly, 1979), and are motivated b

A self is the "me" at the center of experience - a continuallyself-interest and self-concern across a wide variety of dom

developing sense of awareness and agency that guides(Greenwald, action 1980). In broad strokes, people in North Ameri

and takes shape as the individual, both brain andcontexts body, are smarter, kinder, healthier, and happier when t

becomes attuned to the various environments it inhabits. Selves selves are affirmed or when situations are self or identity con

are thus psychological realities that are both biologically

ent than when selves are threatened or when situations are iden

(LeDoux, 1996; Northoff et al., 2006) and socioculturally

incongruent (e.g., Oyserman, 2008; Steele, Spencer, & Arons

(Markus & Kitayama, 1991) rooted. Selves develop as individ-2002; Taylor, Lerner, Sherman, Sage, & McDowell, 2003).

uals attune themselves to contexts that provide different solu-Researchers have now moved beyond the traditional conf

of research within North America and have observed contexts

tions to the universal questions of "Who or what am I?",

"What should I be doing?", and "How do I relate to others?"like those in East Asia and South Asia. These contexts are quite

(Kitayama & Uchida, 2005; Markus & Hamedani, 2007). They

differently arranged than North American ones and are ani-

are simultaneously schémas of past behavior and patterns for

mated by different ontological understandings of what a person

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

422 Markus and Kitayama

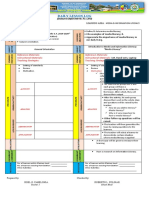

Fig. I. The mutual constitution of cultures and selves. Figure adapted from Markus and Kitayama ( 1 994) and

Fiske et al. (1998).

is. These comparisons

such as world, environment,

among contexts, cultural

people

systems, soc

world have systems, social

revealed structures, institutions, practices,

differences polic

in

terns of attuning

meanings, to norms,contexts,

and values, that give form and that

direction

As a result, behavior. Culture

many is not a stable set of beliefs or values-

processes that perc

motivation, relational

reside inside people. Instead,andculture is located

intergr

in the world,

thought to be basic,

in patterns of ideas,universal, and

practices, institutions, products, and arti-

ing, have been facts (e.g., Adams & Markus,

found to 2004; vary Atran, Medin,dram & Ross,

parisons, the influence

2005; Chui & Hong, 2006; Kroeber &of the

Kluckhohn, 1952; s

becomes even more

Shweder, 2003). apparent.

With this definition, the emphasis in the study of culture and

What Is Culture and How Does It Constitute self is not on studying culture as collections of people - the

Japanese, the Americans, the Whites, the Latinos - but is instead

the Self (and Vice-Versa)? on how psychological processes may be implicitly and explicitly

shaped by the

Just as the word self is used to index a family of overlapping butworlds, contexts, or sociocultural systems that

people

not identical terms, the word culture is a stand-in for inhabit. As illustrated in Figure 1, the self (i.e., body,

a similarly

brain,

untidy and expansive set of material and symbolic and psychological tendencies) and the sociocultural

concepts,

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Culture and Self 423

content (i.e., proliferation

ideas, practices

continually ecological

constitute fact

one

the of

mediating philosophy

self and psyc

As indicated Notably,

in Figure the

1 , i

cu

ual; it is

a independence

product of hum

activity as Every

well as context

the thou

individuals of

who both.

have In all

come

context transactions)

shapes the self w

thro

tacit ences

categories ofand goal

culture

input from friend relatiom

sociocultural

is the center and

of relationsh

awareness

reflects carries

these elemen

sociocultural

feelings, anding degrees

actions (A

(i.e.,

change, the 1995). Neverth

sociocultural fo

cycle of these

mutual two sch

constitutio

As a sidered dominant or foundational.

consequence of this

dynamic In an early paper on culture and the self 2000

(Kashima, (Markus &

dynamic in Kitayama,

that 1991), we proposed

the that if one of these schémas

socioc

products, becomes foundational - guiding how cultural ideas,

artifacts, econo practices,

that institutions, and products

comprise it of a culture

are are evaluated, selected,

con

changed and deselectedtime.

over or weeded out - there will be Selves

widespread and

the various important

cultural conte

differences in the nature and functioning of the self

tion, a and in the

focus on psychologicaltheprocesses that aresociocu

rooted in these

deny schémas. Figure 2 is an adaptation and amplification ofand

the

individuality an

even earlier figure representing

most the tight-knitindependent and interdependent

vidual selves (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Thein

participates diagram reflects

athe- var

texts that orizing and empirical work since this time (see

constitute theHeine, 2008; se

might Markus & Kitayama,

include 2003) and depicts two different patternscol

specific

gin, such of

as attuning to

the the social world and two different senses of

family

defined by self or

gender,agency. ethnic

class, birth As shown Figure 2, when an independent

cohort, and schema of self se

ing similar organizes behavior, the primary referent is the individual's own

configurations

spaces will thoughts, feelings, and actions. Alternatively, when

obviously an interde-

diver

experiences pendent

and schema of self organizes

will behavior, the immediate

differ refer-

experiences

ent is the(e.g.,

thoughts, feelings, and actions Markus

of others with whom the

person is in relationship. With an independent self (i.e., an inde-

pendent way of attuning to the social environment or indepen-

What Is dentIndepende

mode of being), interaction with others (actual, imagined,

One or implied) produces a sense of

particularly self as separate, distinct, or inde-

powerful

which pendent from others. These the

prescribe interactions are guided by culturally

norm

the self prescribed individual)

(the tasks that require and encourage the development and an

scientists in various

reification of individual preferences, goals, beliefs, and field

abilities

1858/1973; (as indicated by the Xs in the independent

Mead, 1934; self-schema) and the Tr

rized two use of these attributes as referents and

distinct guides for action. The

types of

be linked to large dotted circle separates close relations from moremod

divergent distant

of sociality relations,

assumes suggesting that people have a sense that

thatthey can move so

of between ingroup and outgroup

instrumental relatively easily.

interests a

Labels for such With an interdependent

socialself (i.e., an interdependent way of

relat

dent, attuning to the social environmentand

egocentric, or interdependent modeindiof

assumes being), interaction

that with others produces a sense of self as con-

individuals a

meaningful nected to, related to, or interdependent with others.relati

through These inter-

social actions are guided by include

relations culturally prescribed tasks that require ge

centric, and encourage fitting in with others (as indicated

communal, and by the Xs co

Shweder & in the overlap between self and others in the

Bourne, interdependent

1984;

The origins self-schema

of in Fig. 2),these

taking the perspective of others,

two reading

contested. the expectations of others,researcher

Some adjusting to others, and using others

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

424

Fig. 2. Independent a

Kitayama (1991) and

as referents for

Further,action.

the

are dotted (those

with a deline

solid l

solid), and they

tion represen

is signif

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Culture and Self 425

line, frequently

In contrast, when the schemaresulting

for self is interdependent with

and outgroup members

others and this schema organizes agency, people will have a (se

It is sense of themselves as partto

important of encompassing social relation-

note th

form of sociality or

ships. People are likely to reference others, of

and to understand in

relationshipstheir individual

are actions as contingent

understo

on or organized by the

choice. actions of others and their relations with

Likewise, these others. Actions

interde

types of independence

rooted in this schema will have different meanings and conse- in

by quences than actions rooted in a with

identification independent schema. Thus, or a

in a

relationship.

lack of speech does not imply aAlthough

lack of thinking, performing well

are likely to

on a taskbeselected by one's

responsive

mother does not imply a preference

mony or affection among

for having choices usurped or a lack of self-efficacy, and attend-

relationshipsing to one's(Kitayama

shortcomings does not imply low self-esteem or et

depression (Iyengar & Lepper, 1999; Kim, 2002; Markus

et al., 2006). Such tendencies instead can reflect an acknowl-

How Do Independence and Interdependence

edgement of one's role or obligations in a particular situation

Shape Psychological Functioning? and an awareness of the significant others with whom one is

The distinction between independence and interdependence as interdependent and who define the self. Similarly, fostering

foundational schémas for the self has proved to be a powerful good relations (Holloway et al., 2009), having concerns about

heuristic for demonstrating how sociocultural contexts canone's enemies (Adams, 2005), experiencing a heightened sensi-

shape self-functioning and psychological functioning (fortivity to others' evaluations (Nisbett, 1993), having greater con-

detailed reviews, see A. Fiske et al., 1998; Heine, 2008; cern for others' actions than for thoughts (A.B. Cohen & Rozin,

Kitayama & Cohen, 2007). Returning to the selection of find- 2001), and exhibiting relatively little concern with getting to

ings described in the opening paragraphs of this article, all of choose (Snibbe & Markus, 2005) are also consistent with a sense

the differences cited can be explained in some important partof one's self as being related to others and with an awareness of

by the independent and interdependent patterns of sociality.the relatively larger role of others in influencing who you are and

Across all of these examples, the ideas and/or practices in onewhat you should be doing. Moreover, even the same region of

setting place relatively more emphasis on the attributes of thethe brain is activated by both significant others (mother) and the

individual and their expression as the form of agency, whereasself for people in Chinese contexts (Zhu et al., 2007), which

the ideas and practices of the comparison setting place rela- serves as yet another type of evidence for the psychological real-

tively more emphasis on relationships and social responsive- ity of this interdependent sense of agency.

ness and the maintenance of these relationships as the form Together these findings, and hundreds more like them,

of agency. powerfully demonstrate that independence and interdepen-

When the schema for self is independent from others and dence have significant psychological consequences - for

this schema organizes agency, people will have a sense of cognition, emotion, motivation, morality, relationships, inter-

themselves as separate and will be relatively likely to focus group processes, health, and well-being - and the field's view

on, reference, and express their own thoughts, feeling, and of these concepts is broadening. For example, viewing aspects

goals. For example, people in North American settings are of the world and one's self as distinct objects and attributes that

likely to speak out and emphasize their good qualities, are separate from their contexts (e.g., Masuda et al., 2005), per-

because in doing so they can express their defining prefer- ceiving one's self to be consistent across situations (e.g., Suh,

ences or attributes (Kim, 2002). Highlighting one's successes 2002), and experiencing well-being in the pursuit of fun and

after a performance functions similarly by drawing attention enjoyment (e.g., Oishi & Diener, 2001) derive from and con-

to one's positive, defining attributes (Markus et al., 2006). tribute to a sense of independence. Alternatively, paying atten-

In addition, people in North American settings decide tion to the context, others, role obligations, and duties; taking

whether or not to help someone based on their preferences, the other's perspective; and cultivating feelings of balance or

and normatively good actions follow from the expression of calm in relations with others derive from and serve to further

these preferences (Miller & Bersoff, 1998). Similarly, choice realize a sense of interdependence (e.g., D. Cohen &

enhances the performance of middle-class Americans, and Hoshino-Browne, 2005; Mesquita, 2001; Tsai, Louie, Chen,

they seek out and construct their actions in terms of choice & Uchida, 2007).

because choice allows the expression of these preferences

and thus serves to affirm the self (Iyengar & Lepper, 1999;

Snibbe & Markus, 2005). Lastly, individual achievement and What Are the Continuing Challenges

success are associated with happiness in independent settings

and Controversies in the Study of Culture

because achievement signals positive internal attributes

and Self?

(Kitayama et al., 2009). In all cases, these actions reflect set-

tings that foster the sense that the individual is the source of We now know considerably more about cultural variation in

thought, feeling, and action. the self and, further, have gained numerous insights into the

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

426 Markus and Kitayama

ways in which that

the cultural variation

self assessed in terms

is of collective

shaped artifacts b

time, shapes culture.

is bound to be far greater thanA number

the corresponding cultural var-

unresolved, iation as assessed in terms of self-reported

unaddressed, or beliefsotherw

and values

sely debated. (Morling & Lamoreaux, 2008). Another approach to assessing

culture is a situation sampling method in which participants

generate situations that are associated with particular thoughts

Measurement of Culture and feelings (i.e., feeling good, feeling in control). Researchers

Numerous researchers have assumed that at least some ele- then give these situations to another group of respondents to see

ments of culture should be measurable in a self-report format

if envisioning these particular situations produces the psycho-

logical tendencies that gave rise to them (e.g., Kitayama,

and have administered a variety of cultural value question-

naires. One most prominent example is a large-scale cross-

Markus, Matsumoto, & Norasakkunkit, 1997).

cultural survey Hofstede administered on IBM employees Both the personal, explicit aspects and the more collective,

across the world (Hofstede, 1980). Schwartz and colleagues

tacit aspects are important in understanding and, thus, measur-

have tested cultural variations in self-reported value priorities

ing culture. One important step for the field is, on the one hand,

(e.g., Schwartz, 1992). Also notable are some scales assessing

to articulate exactly how the two aspects of culture might be

individualism and collectivism, tightness and looseness, or

dynamically related and, on the other, to specify how collective

independent and interdependent self-construal (e.g., Gelfand,

cultural environments that structure a person's life might inter-

Nishii, & Raver, 2006; Singelis, 1994; Triandis, 1995). act

Onewith the person's personal beliefs and values to determine

his or her psychological behaviors (D. Cohen, 2007). Effort

strength of this approach is that measurement is relatively

along this line would require simultaneous examinations of

straightforward and involves evaluating attributes or items

along rating scales. Cultures can be quantified on different

groups that vary systematically in terms of collective artifacts

dimensions and can be readily compared. One potential prob-

and individuals within each group who vary systematically in

terms of their personal beliefs and values.

lem is that it is not always obvious whether and to what extent

culture can be reduced to each individual's beliefs, values, or

behavioral observations. Another important challenge stems

Measurement

from the fact that it is not known whether one's beliefs or val- of Self

Parallel issues of measurement can be raised for the self as

ues are always accessible to one's conscious reflection. If not,

the validity of self-report questionnaires may be called into

well. In recent decades, research and theorizing about the self

question. has been anchored on particular methods that assess how peo-

Other researchers have, instead, taken the fact that culture is

ple consciously think about themselves. This is necessary and

actually quite tacit and taken for granted as a starting point important work because in settings like those in North Amer-

(Markus & Hamedani, 2007). These researchers also assume ica, which focus on and encourage an explicit understanding

that beliefs and values such as individualism and collectivism of the self, the explicit self-concept can be shown to mediate

are important components of culture. How they differ from the and regulate much of behavior (e.g., Oyserman, 2008). Within

first group of researchers stems from an observation that cul- this tradition of work, the most face-valid measure of self is

tural beliefs and values - especially those that are important how people describe themselves. One most commonly used

and, thus, have constituted each culture's practices, institu- research tool in this school of thought is the 20 statements test,

tions, and its ways of life - are, by definition, inscribed into

wherein participants are asked to describe themselves in 20 dif-

these practices, institutions, and ways of life. These beliefs ferent

and ways (e.g., Cousins, 1989).

values are externalized and materialized in the world An equally robust and time-honored tradition of research on

(D' Andrade, 1995) and, thus, no longer need to be the packed in emphasized the crucial role of unconscious self-

self has

the head of each individual member of the cultural regulation. group. ForThe self, as we have noted, encompasses not only

example, contemporary American society as a whole may

what thebe

person regards himself or herself to be, but also how

described as individualistic, not so much because many peoplemem-

regulate their behavior in somewhat specific and char-

bers of this society strongly endorse individualistic values

acteristic fashions. This view suggests that there are many ways

(although this could also be true), but rather because ofthis

beingsoci-

or senses of the self that are not represented in one's

ety is composed of interpersonal routines, situations, explicit beliefs. Such aspects are likely to be implicit in the

practices,

social institutions, and social systems that are fundamentally sense that they do not directly index thoughts and feelings

individualistic. about the self, but instead reflect differences in attending, per-

On the basis of this reasoning, some researchers haveceiving, feeling, thinking, and acting that arise as people attune

assessed collective artifacts of culture, such as ads in TV or themselves to contexts that provide different solutions to the

popular magazines, children's books, religious texts, and news existential questions of who or what am I and what should I

coverage of sporting events (Kim & Markus, 1999; Markus be doing. These implicit psychological tendencies are most

et al., 2006; Tsai et al., 2007; Tsai, Miao, & Seppala, 2007).likely to be unconscious and may be equally consequential in

An extensive review of this literature has concluded that cul-

organizing one's psychological behaviors. Moreover, there is

tures do differ in terms of collective artifacts and, moreover,

no reason to assume that the explicit and the implicit aspects

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Culture and Self 427

of the self are closely

independence or interdependence is associated with different link

2009). cues (such as singular vs. plural pronouns).

One crucial question for the dynamic social constructivist

view is to specify what particular knowledge might be lined

What Does Cultural Priming Mean? to different cultural icons. For example, Chinese icons may

One important development of cultural psychological work in well call out behaviors that are common in China. Although

the last decade was the proliferation of priming work. This lit- this might be true in a general, abstract sense, it might also

erature highlights two related, but theoretically distinct, meth- be the case that within any given cultural context, specific icons

odologies. One approach assumes that cultures carry icons that might be associated with, and could thus be used to call out,

are associated with commonly available meanings and prac- particular aspects of Chinese culture. A parallel question can

tices. These icons may then be used to "call out" mental repre- be raised for the situated cognition approach. Although the gen-

sentations of relevant cultural meanings and practices. For eral concepts of independence and interdependence are likely

example, one set of pioneering studies tested bicultural Hong to be commonly available across many, and perhaps all, cul-

Kong Chinese and showed that they either exhibit a prototypi- tures, it is far from clear whether independence and interdepen-

cally East Asian response or a prototypically Western response dence mean the same thing across cultures - most theorizing on

depending on the cultural icons used in the priming manipula- the topic suggests that they do not. Think about a Chinese adult

tion (Hong, Morris, Chiù, & Benet-Martinez, 2000). When par- who regards himself as very independent and self-reliant

ticipants were exposed to Chinese scenes, such as dragons and because he is capable of providing financial assistance for his

the Great Wall, bicultural Hong Kong Chinese showed more ailing parents. Even though this behavior is regarded as an

prototypically interdependent behaviors, but when exposed to instance of independence in one cultural community, the same

American scenes, such as the Statue of Liberty or Liberty Bell, behavior may easily be reconstrued as an instance of interde-

they showed prototypically independent behaviors. Because pendence in another. It seems quite clear that the priming

the pertinent cultural knowledge is considered to construct psy- approaches will be enriched substantially when supplemented

chological experience in dynamic interaction with certain per- with an in-depth analysis of the nature of cultural knowledge

sonality characteristics of the actor, such as the need for that is called out by specific priming stimuli.

cognitive closure, this approach is called the dynamic social Another important question that must be addressed is

constructivist approach. whether knowledge is always a mediating element in all

Another approach is based on the assumption that the sché- forms of cultural influence. That is to say, can culture's influ-

mas of independence and interdependence are, in large part, ences be most fully understood in terms of the ability of cul-

universal and shared across cultures (Oyserman & Lee, tural contexts to activate key psychological constructs such as

2007). With this assumption, one might suppose that cultures independence and interdependence? An alternative perspec-

are very different in terms of availability of cues that call out tive, and the one we have assumed here, is that that sociocul-

one or the other schema. Within this theoretical framework, a tural contexts afford cultural practices that become

number of researchers have investigated potential effects of a incorporated into the behavioral routines of daily life (see

variety of priming manipulations designed to call out either Fig. 1). These practices often reflect and foster orientations

independence or interdependence. For example, participants toward and values of independence and interdependence.

may be presented with a paragraph describing the behaviors From the very beginning of one's life, then, individuals are

of a single individual who was referred to as "I" or a paragraph encouraged to be engaged in such practices, initially only

in which the same set of behaviors was attributed to a group passively but gradually more and more actively. Repeated

described as "we" (Brewer & Gardner, 1996). Frequent refer- and continuous engagement in some select set of practices

ence to the personal self ("I") may be assumed to call out inde- or situations involving certain features, such as self-

pendence, whereas frequent reference to the relational self expression in an independent cultural context or adjustment

("we") may be assumed to call out interdependence. Because or conformity in an interdependent cultural context, may lead

this approach implies that the generic schémas of independence to some characteristic patterns of psychological responses.

and interdependence are embedded in specific social situations These responses may be initially deliberate and effortful, but

that carry different sets of cues that call out the generic sché- they will eventually be highly practiced and thus automa-

mas, it is called the situated cognition approach. tized. In fact, recent neuroscience evidence suggests that

These priming methods have been highly instrumental in repeated engagement in certain tasks, including cultural tasks

advancing our understanding about a proximate mechanism such as self-expression or conformity, is likely to cause cor-

by which culturally specific behaviors may be induced. Once responding changes in brain pathways (see Han & Northoff,

culturally relevant knowledge is activated, this knowledge 2008; Kitayama & Park, 2009, for reviews). It is evident,

mediates the effect of culture on behavior. The two approaches then, that culture may influence psychological processes not

vary in the nature of this knowledge. Whereas the dynamic only by providing priming stimuli that bias one's responses

social constructivist approach assumes that culture-specific in one way or another, but also by affording a systematic

knowledge is closely linked to cultural icons, the situated cog- context for development in general and the establishment

nition approach hypothesizes that generic knowledge of of systematic response tendencies in particular.

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

428

Concluding

References

Rem

In the Adams, G. three

last (2005). The cultural grounding of personal

deca relationship:

cultural Enemyship in North American and West African worlds. Journal

psychologic

classNorth of Personality and Social Psychology , 88, 948-968.

Americans

AmericansAdams, G.,as

& Markus, H.R.one(2004). Toward a conception

of of culture t

of this suitable for a social psychology of culture. In M. Schaller &

Euro-Americ

learned С. S. Crandall

a great(Eds.), The psychological foundations

deaof culture

humans - those from middle-class North American and West- (pp. 335-360). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

ern European contexts (Arnett, 2008; Markus, Kitayama, &Adams, G. (2005). The cultural grounding of personal relationship:

Heiman, 1997). People engaging in these contexts are likely Enemyship in North American and West African worlds. Journal

to reveal relatively high levels of self-esteem, self-efficacy, of Personality and Social Psychology , 88, 948-968.

optimism, or intrinsic motivation and express a desire for mas-Arnett, J.J. (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology

tery, control, achievement, choice, self-expression, or unique- needs to become less American. American Psychologist , 63,

602-614.

ness. They also like to feel happy, upbeat, and successful,

and their agency often takes the form of influencing others orAtran, S., Medin, D.L., & Ross, N.O. (2005). The cultural mind: Envi-

the world. We can now confidently say that this robust set of ronmental decision making and cultural modeling within and

psychological tendencies - with its many world-making and across populations. Psychological Review , 112 , 744-776.

world-maintaining consequences - is not, however, anBanaji, M., & Prentice, D. (1994). The self in social contexts. Annual

expression of a universal human nature. Instead, it reflects the Review of Psychology , 45, 297-332.

particular worlds in which these people engage. These well- Brewer, M.B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this "we"? Levels of

documented self-serving and self-interested tendencies are cre- collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality

ated, fostered, and maintained by widely distributed ideas, such and Social Psychology , 71, 83-93.

as the importance of individual achievement, that have been Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

reinforced and instituted by dense networks of everyday prac- University Press.

tices, such as complimenting and praising one another for indi-Carver, C.S., & Scheier, M.F. (1998). On the self regulation of beha-

vidual performance, frequently distributing awards and honors vior. New York: Cambridge University Press.

in classrooms and workplaces, and promoting the self in situa-Cohen, A.B., & Rozin, P. (2001). Religion and the morality of mental-

tions like applying for jobs. These tendencies for self- ity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 81, 697-710.

expression, feeling good about the self, and controlling the Cohen, D. (2007). Methods in cultural psychology. In S. Kitayama &

environment are further encouraged by products such as coffee D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (pp. 196-236).

New York: Guilford.

mugs, bumper stickers, self-help books, automobile advertise-

Cohen, D., & Hoshino-Browne, E. (2005). Insider and outsider per-

ments, medications, perfume, and cleaning products that exhort

people to "Be a star," "Take control," "Never follow," and spectives on the self and social world. In R.M. Sorrentino,

"Get happy." Notably, when people inhabit many other kinds D. Cohen, J.M. Olson & M.P. Zanna (Eds.), Culture and social

of worlds that are configured with ideas, practices, and institu- behavior : The Ontario symposium (Vol. 10, pp. 49-76).

tions that do not construct the self as the primary source of Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

action, strikingly different psychological tendencies areCousins, S.D. (1989). Culture and self-perception in Japan and the

revealed. United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 56,

124-131.

Although a vast amount of both theoretical and empirical

work remains before researchers can more fully specify the D' Andrade, R.G. (1995). The development of cognitive anthropology.

cycles of mutual constitution between cultures and selves, this Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

work is steadily changing the way psychology understands theDumont, L. (1977). From Mandeville to Marx: The genesis and tri-

person. Psychologists and all behavioral scientists are less cer- umph of economic ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

tain about what can be designated as basic or universal psycho-Fiske, A., Kitayama, S., Markus, H.R., & Nisbett, R.E. (1998). The

logical process and more certain that it is not possible to cultural matrix of social psychology. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, &

develop a comprehensive human psychology by focusing G. Lindzey, The handbook of social psychology, vol. 2 (4th ed.,

solely on the individual and on what is inside that individual pp. 915-981). San Francisco: McGraw-Hill.

(e.g., Barrett, Mesquita, & Smith, in press; Bruner, 1990). Such Fiske, S.T., & Taylor, S.E. (1994). Social cognition. (2nd ed.).

a psychology will require a focus on humans' remarkable Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley.

capacity to create cultures and then to be shaped by them. Gelfand, M.J., Nishii, L.H., & Raver, J.L. (2006). On the nature and

importance of cultural tightness-looseness. Journal of Applied Psy-

chology, 91, 1225-1244.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests Greenfield, P.M. (2009). Linking social change and developmental

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect change: Shifting pathways of human development. Developmental

to their authorship or the publication of this article. Psychology, 45, 401-418.

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Culture and Self 429

Greenwald, Markus,

A.G. (1980).

H.R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implica- Th

revision of tions

personal histo

for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological

603-618. Review , 98, 224-253.

Han, S., & Northoff, G. (2008). Culture-sensitive neural substrates

Markus, of

H.R., & Kitayama, S. (1994). A collective fear of the collec-

human cognition: A transcultural neuroimaging approach. Nature

tive: Implications for selves and theories of selves. Personality and

Reviews Neuroscience , 9, 646-654. Social Psychology Bulletin , 20, 568-579.

Heine, S.J. (2008). Cultural psychology. New York: Norton.Markus, H.R., & Kitayama, S. (2003). Models of agency: Sociocul-

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differ-

tural diversity in the construction of action. In V.M. Berman &

ences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. J.J. Berman (Eds.), Nebraska symposium on motivation: Cross-

Holloway, R.A., Waldrip, A.M., & Ickes, W. (2009). Evidence that a

cultural differences in perspectives on the self (Vol. 49, pp.

1-58). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

simpático self-schema accounts for differences in the self-concepts

and social behavior of Latinos versus Whites (and Blacks).Markus,

JournalH.R., Kitayama, S., & Heiman, R. (1997). Culture and

of Personality and Social Psychology , 96 , 1012-1028. "basic" psychological principles. In E.T. Higgins &

Hong, Y., Morris, M.W., Chiù, С., & Benet-Martinez, V. (2000).A.W.

Mul-Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic

principles

ticultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and (pp. 857-913). New York: Guilford.

cognition. American Psychologist , 55, 709-720. Markus, H.R., & Moya, P. (Eds.). (2010). Doing race: 21 essays for

Iyengar, S.S., & Lepper, M. (1999). Rethinking the value of choice: A century. New York: W.W. Norton.

the 21st

Markus,

cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality H.R., Uchida, Y., Omoregie, H., Townsend, S., &

and Social Psychology , 76, 349-366. Kitayama, S. (2006). Going for the gold: Models of agency in Japa-

Kashima, Y. (2000). Conceptions of culture and person for psychol-

nese and American contexts. Psychological Science, 17, 103-1 12.

ogy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology , 31, 14-32. Marx, K. (1973). Grundrisse: Foundations of the critique of political

economy

Kim, H.S. (2002). We talk, therefore we think? A cultural analysis of (M. Micolaus, Trans.). New York: Random House.

the effect of talking on thinking. Journal of Personality and(Original

Social work published 1857-1858).

Psychology , 83 , 828-842. Masuda, T., Ellsworth, P.C., Mesquita, В., Leu, J., Tañida, S., & Van

Kim, H., & Markus, H.R. (1999). Deviance or uniqueness, harmony or

de Veerdonk, E. (2005). Placing the face in context: Cultural dif-

conformity? A cultural analysis. Journal of Personality and Social

ferences in the perception of facial emotion. Journal of Personality

Psychology , 77, 785-800. and Social Psychology, 94, 365-381.

Kitayama, S., & Cohen, D. (2007). Handbook of cultural psychology.

Mead, G.H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago: University of

New York: Guilford. Chicago Press.

Kitayama, S., Duffy, S., & Uchida, Y. (2007). Self as cultural mode Mesquita,

of В. (2001). Emotions in collectivist and individualist con-

being. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural texts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 68-74.

psychology (pp. 136-173). New York: Guilford Press. Mesquita, В., Barrett, L.F., & Smith, E.R. (2010). The mind in context.

Kitayama, S., Markus, H.R., Matsumoto, H., & Norasakkunkit, V. New York: Guilford Press.

(1997). Individual and collective processes in the construction of the

Miller, J.G., & Bersoff, D.M. (1998). The role of liking in perceptions

self: Self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in of the moral responsibility to help: A cultural perspective. Journal

Japan .Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72 , 1245-1267. of Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 443-469.

Kitayama, S., Park, H., Sevincer, A.T., Karasawa, M., & Uskul, A.K.

Morling, В., & Lamoreaux, M. (2008). Measuring culture outside the

(2009). A cultural task analysis of implicit independence: Compar- head: A meta-analysis of individualism - collectivism in cultural

ing North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. Journal of products. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12, 199-221 .

Personality and Social Psychology , 97, 236-255. Nisbett, R.E. (1993). Violence and U.S. regional culture. American

Kitayama, S., & Park, J. (2009). The social self and the social brain: A Psychologist, 48, 441^49.

Northoff, G., Heinzel, A., de Greek, M., Bermpohl, F.,

perspective of cultural neuroscience. Manuscript submitted for

publication. Dobro wolny, H., & Panksepp, J. (2006). Self-referential process-

Kitayama, S., & Uchida, Y. (2005). Interdependent agency: An alter- ing in our brain: A meta-analysis of imaging studies on the self.

native system for action. In R.M. Sorrentino, D. Cohen, Neurolmage, 1, 440-457.

J.M. Olson, & M.P. Zanna (Eds.), Cultural and social behavior:Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2001). Goals, culture, and subjective well-

The Ontario symposium (Vol. 10, pp. 137-164). Mahwah, NJ: being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1674-1682.

Erlbaum. Oyserman, D. (2008). Racial-ethnic schémas: Multidimensional iden-

Kroeber, A.L., & Kluckhohn, C.K. (1952). Culture: A critical review tity based motivation. Journal of Research in Personality, 42,

of concepts and definitions. New York: Random House. 1186-1198.

LeDoux, J.E. (1996). The emotional brain. New York: Simon & Oyserman, D., & Lee, W. (2007). Priming "culture": Culture as situ-

Schuster. ated cognition. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of

Markus, H.R., & Hamedani, M.G. (2007). Sociocultural psychology: cultural psychology. New York: Guilford.

The dynamic interdependence among self-systems and social sys-Ross, M., & Sicoly, F. (1979). Egocentric biases in availability and

tems. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural attribution. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37,

psychology (pp. 3-46). New York: Guilford. 322-336.

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

430 Markus and Kitayama

Schwartz, S.H. Taylor, S.E., Lerner,Universals

(1992). J.S., Sherman, D.K., Sage, R.M., & in t

ues: TheoreticalMcDowell,

advancesN.K. (2003). Are self-enhancingand

cognitions associated

emp

M.P. Zanna (Ed.),

with healthyAdvances in

or unhealthy biological profiles? Journal of Personal- exp

(Vol. 25, pp. ity and Social Psychology,

1-65). New 85, 605-615. York: Ac

Shweder, R. Tönnies, F. (1988).

(2003). Why Community and society

do (C.P. Loomis,

men Trans.). ba

chology. New York: Harper & Row.

Cambridge, MA: (Original work published

Harvard 1887).

Shweder, R.A., Triandis,

& H.C. (1989). The self and social behavior

Bourne, L. in differing

(1984).cul-

vary tural contexts. Psychological Review,

cross-culturally? In93, R.A.

506-520. Shw

ture theory : Triandis, H.C. (1995). on

Essays Individualism and collectivism. Boulder,

mind, CO:

self,

York: Westview.

Cambridge University Press.

Singelis, T.M. Tsai, J.L., Louie, J., Chen,

(1994). The E.E., & Uchida, Y. (2007). Learning what

measurem

pendent feelings to desire: Socialization of ideal

self-construals. affect through children's

Personalit

tin , 20 , storybooks. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33,

580-591.

Snibbe, A.C., & 17-30.

Markus, H.R. (2005

want: Tsai, J.L., attainment,

Educational Miao, F., & Seppala, E. (2007). Good feelings in Christian-

agenc

sonality and ity and Buddhism:

Social Religious differences in ideal affect. Personal- ,

Psychology 8

Steele, C.M., ity and Social Psychology

Spencer, Bulletin, 33, 409-421.

S.J., & Aron

group image: Wood, N., & Cowan,

The N. (1995). The cocktail party phenomenon revis-

psychology of s

threat. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.),

ited: How frequent are attention Advanc

shifts to one's name in an irrele-

chology (Vol. vant auditory

34, pp. channel? Journal of Experimental Psychology:

379-440). Sa

Suh, E.M. (2002).

Learning Culture,

Memory, and Cognition, 21, 255-260. identi

well-being. Personality and

Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Fan, J., & Han, S. (2007). Neural Soci

basis of cultural

1378-1391. influence on self-representation. Neurolmage, 34, 1310-1316.

This content downloaded from

103.133.254.25 on Wed, 14 Feb 2024 04:37:02 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- The Self and Social Behavior in Differing Cultural ContextsDocument15 pagesThe Self and Social Behavior in Differing Cultural ContextsGalih Ismiansyah0% (1)

- R02 - Shaver 1987 - Emotion Knowledge. Further Exploration of A Prototype ApproachDocument26 pagesR02 - Shaver 1987 - Emotion Knowledge. Further Exploration of A Prototype ApproachGrupa5No ratings yet

- No More Rejection! PDFDocument16 pagesNo More Rejection! PDFPriyobroto Chokroborty100% (1)

- 8 When Is A Compliment Not A Compliment Evaluating Expressions of Positive StereotypesDocument8 pages8 When Is A Compliment Not A Compliment Evaluating Expressions of Positive StereotypesAmeen Ali Al-JammalNo ratings yet

- Life Histories of the Dobe !Kung: Food, Fatness, and Well-being over the Life-spanFrom EverandLife Histories of the Dobe !Kung: Food, Fatness, and Well-being over the Life-spanNo ratings yet

- Influence of Self-Reported Distress and Empathy and Egoistic Versus Altruistic Motivation For HelpingDocument13 pagesInfluence of Self-Reported Distress and Empathy and Egoistic Versus Altruistic Motivation For HelpingYi-Hsuan100% (2)

- Psychosocial Development and ReadingDocument19 pagesPsychosocial Development and ReadingRo Del100% (1)

- Competencies With Proficiency LevelsDocument8 pagesCompetencies With Proficiency LevelsLucia Doan100% (1)

- How To Improve Your Spoken EnglishDocument22 pagesHow To Improve Your Spoken EnglishSyahamah FuzaiNo ratings yet

- 2.cultures and Selves - A Cycle of Mutual ConstitutionDocument11 pages2.cultures and Selves - A Cycle of Mutual ConstitutionBlayel FelihtNo ratings yet

- What Is CultureDocument11 pagesWhat Is CultureGerald PolerNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Culture - Security in The United States and JapanDocument12 pagesAttachment and Culture - Security in The United States and JapanorchidwonderlandNo ratings yet

- Loyalty Without Conformity Balancing The PDFDocument18 pagesLoyalty Without Conformity Balancing The PDFRowena FinleyNo ratings yet

- Cross MadsonDocument34 pagesCross MadsonCorina MitrulescuNo ratings yet

- Culture and The Self Implications For Cognition emDocument31 pagesCulture and The Self Implications For Cognition emGhender TapecNo ratings yet

- On The Universality and Cultural Specificity of Emotion Recognition: A Meta-AnalysisDocument34 pagesOn The Universality and Cultural Specificity of Emotion Recognition: A Meta-AnalysisFernando Pepe FalcónNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Differences-22Document15 pagesCross Cultural Differences-22joekvedusaNo ratings yet

- 2002ElfenbeinMeta PDFDocument33 pages2002ElfenbeinMeta PDFSelenaNo ratings yet

- Wang Mallinckrodt Attachment Cultural 2006 2Document14 pagesWang Mallinckrodt Attachment Cultural 2006 2kathy_burgNo ratings yet

- 496.full Who Helps YouDocument14 pages496.full Who Helps YouValerita83No ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTDDocument9 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTDAna BabaNo ratings yet

- 596Document9 pages596wawaisnadNo ratings yet

- Aip1126 1Document7 pagesAip1126 1Ivan MoriáNo ratings yet

- Elements Lay Theory Groups: Types Groups, Relational Styles, Perception Group EntitativityDocument12 pagesElements Lay Theory Groups: Types Groups, Relational Styles, Perception Group EntitativityFor JusticeNo ratings yet

- Hobfoll Communal 2002Document39 pagesHobfoll Communal 2002talla ghaffarNo ratings yet

- Reproducing Gender in Counseling and PsychotherapyDocument9 pagesReproducing Gender in Counseling and PsychotherapyMelike ÖzpolatNo ratings yet

- 20 JAP20200620 StressDocument16 pages20 JAP20200620 StressIsra Nur FitriNo ratings yet

- NSP 007Document15 pagesNSP 007Makanudo.No ratings yet

- Riel A Eta LJ Social Personal Relationships 2010Document23 pagesRiel A Eta LJ Social Personal Relationships 2010Felipe Botero RojasNo ratings yet

- Diversity in Organizations: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?Document11 pagesDiversity in Organizations: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going?Wenaldy AndarismaNo ratings yet

- ExaminingtheImpact PreproofVersionDocument36 pagesExaminingtheImpact PreproofVersionlinhb2006352No ratings yet

- Personality and CultureDocument31 pagesPersonality and CultureDavid Green100% (1)

- 2017 Levensonetal EmotionDocument22 pages2017 Levensonetal EmotionLiliaa NoahNo ratings yet

- fischer2006Document14 pagesfischer2006Maie RaoufNo ratings yet

- Many Forms of Culture: American Psychologist May 2009Document12 pagesMany Forms of Culture: American Psychologist May 2009Melgie Ann AmbatNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience of Intergroup RelationsDocument74 pagesNeuroscience of Intergroup RelationsНадежда МорозоваNo ratings yet

- 2008 Savani Markus Conner Let Your Preference Be Your GuideDocument16 pages2008 Savani Markus Conner Let Your Preference Be Your GuideSeñor panNo ratings yet

- Haidt 2009Document11 pagesHaidt 2009Jovana MarNo ratings yet

- Culture and Emotion - NobaDocument18 pagesCulture and Emotion - NobaHalima SadiaNo ratings yet

- Witkower, Z, Tracy, J, 2020, We Don't Make Weir FacesDocument2 pagesWitkower, Z, Tracy, J, 2020, We Don't Make Weir FacesdanijaNo ratings yet

- Psychological Science: Aging and Wisdom: Culture MattersDocument9 pagesPsychological Science: Aging and Wisdom: Culture MattersJosé Luis SHNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in Cross Cultural Psych PDFDocument14 pagesEthical Issues in Cross Cultural Psych PDFFERDY100% (1)

- AcculturationDocument11 pagesAcculturationZiyad FiqriNo ratings yet

- KoropeckyjCox SinglesSocietyScience 2005Document8 pagesKoropeckyjCox SinglesSocietyScience 2005sanjayrajanand18No ratings yet

- Emergence of CultureDocument7 pagesEmergence of CultureGarriy ShteynbergNo ratings yet

- Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination 3Document26 pagesPrejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination 3Veronica TosteNo ratings yet

- Edwards 1999 Emotion DiscourseDocument22 pagesEdwards 1999 Emotion DiscourseRebeca CenaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 150.244.160.132 On Sun, 13 Nov 2022 14:40:14 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 150.244.160.132 On Sun, 13 Nov 2022 14:40:14 UTClisboa StoryNo ratings yet

- Emotion Knowledge Further ExplorationDocument26 pagesEmotion Knowledge Further ExplorationVictoria GrantNo ratings yet

- A7-Effective Writing Feedback and GradingDocument12 pagesA7-Effective Writing Feedback and GradingKerubo PriscahNo ratings yet

- Articulo A ExponerDocument7 pagesArticulo A ExponerDavidNo ratings yet

- Afrocentric ApproaachDocument14 pagesAfrocentric ApproaachRowida aliNo ratings yet

- Klompas Life20experiences20of20people20who20stutterDocument32 pagesKlompas Life20experiences20of20people20who20stutterasyaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2666518223000025 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S2666518223000025 MainLaura NituNo ratings yet

- Jay2009 PDFDocument9 pagesJay2009 PDFCharmaine berNo ratings yet

- Music Therapy As An Anti-Oppressive Practice: The Arts in PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesMusic Therapy As An Anti-Oppressive Practice: The Arts in PsychotherapymeytiNo ratings yet

- Clark Et Al. - 2019 - Tribalism Is Human NatureDocument6 pagesClark Et Al. - 2019 - Tribalism Is Human NatureAnkur GargNo ratings yet

- Japanese Psychology and CultureDocument30 pagesJapanese Psychology and CultureMiguel Agustin FranciscoNo ratings yet

- 452Document29 pages452Liyana HanimNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022103109000894 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0022103109000894 Main1603365No ratings yet

- Zimbardo Psych Make Difference 2005Document14 pagesZimbardo Psych Make Difference 2005Laura Daniela Florez CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Prejudice SechristDocument25 pagesPrejudice SechristZsuzsi AmbrusNo ratings yet

- Developmentalpsychologyresearch SAchapterDocument27 pagesDevelopmentalpsychologyresearch SAchaptermbaligumbi44No ratings yet

- Strangers to Spouses: A Study of the Relationship Quality in Arranged Marriages in IndiaFrom EverandStrangers to Spouses: A Study of the Relationship Quality in Arranged Marriages in IndiaNo ratings yet

- 2020-20211003 LLB TycDocument94 pages2020-20211003 LLB TycGeeta GuptaNo ratings yet

- Organization and Management LA Q2 W4 & W5-f519cDocument3 pagesOrganization and Management LA Q2 W4 & W5-f519cSweet VNo ratings yet

- TLE-Action Research Tarp PresentationDocument9 pagesTLE-Action Research Tarp PresentationCorechie A. Castillo100% (1)

- Disposition Toward Critical ThinkingDocument17 pagesDisposition Toward Critical ThinkingVicente De la OssaNo ratings yet

- Training and DevelopmentDocument13 pagesTraining and DevelopmentSai Vaishnav100% (1)

- School of Management Thought-Based On ShafritzDocument84 pagesSchool of Management Thought-Based On ShafritzAR Rashid100% (1)

- Assignment LL: Submitted To Ankur Makhija Submitted by Tushar Tumsarkar Romisha PriyadarshiniDocument26 pagesAssignment LL: Submitted To Ankur Makhija Submitted by Tushar Tumsarkar Romisha Priyadarshiniromisha100% (1)

- Himalayan Money QuestionsDocument4 pagesHimalayan Money Questionsदीपक सुबेदीNo ratings yet

- Almira Abad Btled 2-A Merry Grace Abella Btled 2-A: PreambleDocument5 pagesAlmira Abad Btled 2-A Merry Grace Abella Btled 2-A: PreambleEl Joy BangkilingNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis Raja Aiman Naim - Checked 1Document58 pagesFinal Thesis Raja Aiman Naim - Checked 1RANNo ratings yet

- Media & Information Literacy 11 Lesson Plan (2019-2020)Document11 pagesMedia & Information Literacy 11 Lesson Plan (2019-2020)Malixi Integrated School (CARAGA - Surigao del Sur)No ratings yet

- BT21303 Syllabus-MQA Format-Revised SPE Standard 1 201112Document4 pagesBT21303 Syllabus-MQA Format-Revised SPE Standard 1 201112Shamri Osman100% (1)

- HopeDocument26 pagesHopeRadhaNo ratings yet

- Social Cognitive TheoryDocument12 pagesSocial Cognitive Theorysharvina gobinath100% (1)

- Unit 3Document20 pagesUnit 3Cherrypink CahiligNo ratings yet

- 2015 Grappling Goal Setting Workbook 1 0Document53 pages2015 Grappling Goal Setting Workbook 1 0johhathan100% (1)

- Chapter 11 - What Drives UsDocument30 pagesChapter 11 - What Drives UsChristina CannilaNo ratings yet

- Internship Report On Compensation Management Practices of Classic Shirts LimitedDocument39 pagesInternship Report On Compensation Management Practices of Classic Shirts LimitedMd. Tanvir Ahamed TuhinNo ratings yet

- Eric Gribowzki VoyagerDocument60 pagesEric Gribowzki VoyagerNathanNo ratings yet

- BT Syllabus and Study Guide 2020-21 FINALDocument19 pagesBT Syllabus and Study Guide 2020-21 FINALarpit soniNo ratings yet

- Model Questions Set Grade 12 Management Quest International CollegeDocument149 pagesModel Questions Set Grade 12 Management Quest International CollegeBishu ThakurNo ratings yet

- Personality Is A Patterned Body of HabitsDocument21 pagesPersonality Is A Patterned Body of HabitsSunny100% (1)

- Leadership, Decision Making, Management and AdministrationDocument106 pagesLeadership, Decision Making, Management and AdministrationCrim Memory AidNo ratings yet

- SW Gradschool Programme July 2016Document10 pagesSW Gradschool Programme July 2016UWE Graduate SchoolNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - HR Management - From Recruitment To Labour RelationsDocument13 pagesChapter 8 - HR Management - From Recruitment To Labour RelationsArsalNo ratings yet