Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Kairos Moment for Public Theology by William F Storrrar

A Kairos Moment for Public Theology by William F Storrrar

Uploaded by

biju.josephCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Christian Worldview: A Student's GuideFrom EverandChristian Worldview: A Student's GuideRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Guide To The Phenomenology of ReligionDocument276 pagesGuide To The Phenomenology of ReligionLeandro Durazzo100% (2)

- The People Rizal Met During His TravelsDocument3 pagesThe People Rizal Met During His TravelsPat80% (35)

- Using The Universal Design For Learning Framework To Plan For All Students in The Classroom: Representation and Visual SupportDocument4 pagesUsing The Universal Design For Learning Framework To Plan For All Students in The Classroom: Representation and Visual SupportCorneal HarperNo ratings yet

- NARRATIVE REPORT ON StakeholdersDocument1 pageNARRATIVE REPORT ON StakeholdersMichelle Fuentes Villoso100% (2)

- A Companion To Public TheologyDocument517 pagesA Companion To Public TheologyTip Our Trip100% (2)

- Brian J. Shanley, O.P. - The Thomist Tradition (2002)Document255 pagesBrian J. Shanley, O.P. - The Thomist Tradition (2002)Caio Cézar Silva100% (1)

- O'Dea, Thomas - 5 Dilemmas in The Institutionalization of ReligionDocument13 pagesO'Dea, Thomas - 5 Dilemmas in The Institutionalization of Religionerwinjason76No ratings yet

- A Public Missiology: How Local Churches Witness to a Complex WorldFrom EverandA Public Missiology: How Local Churches Witness to a Complex WorldNo ratings yet

- EnfjDocument7 pagesEnfjleandrofransoia100% (1)

- Koopman - For God So Loved The World - Some Contours For Public TheologyDocument18 pagesKoopman - For God So Loved The World - Some Contours For Public TheologyKhegan DelportNo ratings yet

- The Mediation of the Spirit: Interventions in Practical TheologyFrom EverandThe Mediation of the Spirit: Interventions in Practical TheologyNo ratings yet

- Postmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusFrom EverandPostmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Engelke, M. Ambient FaithDocument16 pagesEngelke, M. Ambient FaithRodrigo ToniolNo ratings yet

- Missiology and the Social Sciences: Contributions, Cautions and ConclusionsFrom EverandMissiology and the Social Sciences: Contributions, Cautions and ConclusionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Shkul 2009 Reading Ephesians PDFDocument294 pagesShkul 2009 Reading Ephesians PDFmirceapp75% (4)

- Preaching at the Crossroads: How the World - and Our Preaching - is ChangingFrom EverandPreaching at the Crossroads: How the World - and Our Preaching - is ChangingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Issues in Feminist Public Theology - McIntoshDocument19 pagesIssues in Feminist Public Theology - McIntoshShieldmaiden of RohanNo ratings yet

- Safeguarding a Truly Catholic Vision of the World: Essays of A. J. ConyersFrom EverandSafeguarding a Truly Catholic Vision of the World: Essays of A. J. ConyersNo ratings yet

- Introducing Christian Theologies, Volume Two: Voices from Global Christian CommunitiesFrom EverandIntroducing Christian Theologies, Volume Two: Voices from Global Christian CommunitiesNo ratings yet

- Actology: Action, Change, and Diversity in the Western Philosophical TraditionFrom EverandActology: Action, Change, and Diversity in the Western Philosophical TraditionNo ratings yet

- Peter Berger Reflections On The Sociology of Religion TodayDocument12 pagesPeter Berger Reflections On The Sociology of Religion TodayMaksim PlebejacNo ratings yet

- Beyond Secular Faith: Philosophy, Economics, Politics, and LiteratureFrom EverandBeyond Secular Faith: Philosophy, Economics, Politics, and LiteratureMátyás SzalayNo ratings yet

- Steve Bruce Secularization in Defence of UnfashionableDocument254 pagesSteve Bruce Secularization in Defence of UnfashionableZuhal Alfian AkbarNo ratings yet

- The Desecularization of The WorldDocument180 pagesThe Desecularization of The WorldTrevor Jeyaraj Virginia Tech100% (1)

- Book Review The Mission of The Church Five Views IDocument3 pagesBook Review The Mission of The Church Five Views IHarry RonnyNo ratings yet

- Pentecostal Hermeneutics in the Late Modern World: Essays on the Condition of Our InterpretationFrom EverandPentecostal Hermeneutics in the Late Modern World: Essays on the Condition of Our InterpretationNo ratings yet

- Will All be Saved?: An Assessment of Universalism in Western TheologyFrom EverandWill All be Saved?: An Assessment of Universalism in Western TheologyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- This Content Downloaded From 178.222.114.222 On Sun, 15 Nov 2020 11:59:06 UTCDocument30 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 178.222.114.222 On Sun, 15 Nov 2020 11:59:06 UTCZdravko JovanovicNo ratings yet

- Dialectics of Faith-Culture Integration: Inculturation or SyncretismFrom EverandDialectics of Faith-Culture Integration: Inculturation or SyncretismNo ratings yet

- The Priesthood of All Students: Historical, Theological and Missiological Foundations of a Global University MinistryFrom EverandThe Priesthood of All Students: Historical, Theological and Missiological Foundations of a Global University MinistryNo ratings yet

- The Quiet Revolution: The Emergence of Interfaith ConsciousnessFrom EverandThe Quiet Revolution: The Emergence of Interfaith ConsciousnessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Sensus Fidei Recent Theological ReflectionDocument26 pagesSensus Fidei Recent Theological ReflectionLuis FelipeNo ratings yet

- Practicing Theology: Beliefs and Practices in Christian LifeFrom EverandPracticing Theology: Beliefs and Practices in Christian LifeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Listening to the Beliefs of Emerging Churches: Five PerspectivesFrom EverandListening to the Beliefs of Emerging Churches: Five PerspectivesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (26)

- Moving Forward: Poststructuralism and Contextual Approaches To TheologyDocument23 pagesMoving Forward: Poststructuralism and Contextual Approaches To TheologyErin OatesNo ratings yet

- Understanding the Sacred: Sociological Theology for Contemporary PeopleFrom EverandUnderstanding the Sacred: Sociological Theology for Contemporary PeopleNo ratings yet

- The Trinity in a Pluralistic Age: Theological Essays on Culture and ReligionFrom EverandThe Trinity in a Pluralistic Age: Theological Essays on Culture and ReligionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- One Theologian's Personal Journey: John ThornhillDocument13 pagesOne Theologian's Personal Journey: John ThornhillstjeromesNo ratings yet

- Tesis. Jose Miguez Bonino PDFDocument239 pagesTesis. Jose Miguez Bonino PDFErnesto LozanoNo ratings yet

- Living in Gods Creation - Orthodox Perspectives On EcologyDocument268 pagesLiving in Gods Creation - Orthodox Perspectives On EcologydiegoawustNo ratings yet

- Liquid Ecclesiology, Pete WardDocument33 pagesLiquid Ecclesiology, Pete WardLaura Paduraru LuchianNo ratings yet

- Guide To The Phenomenology of ReligionDocument276 pagesGuide To The Phenomenology of ReligionErica Georgiades100% (7)

- AN ESSAY ON PUBLIC THEOLOGY-1995 by Ausaf AliDocument24 pagesAN ESSAY ON PUBLIC THEOLOGY-1995 by Ausaf Alibiju.josephNo ratings yet

- The Disruption of Evangelicalism: The Age of Torrey, Mott, McPherson and HammondFrom EverandThe Disruption of Evangelicalism: The Age of Torrey, Mott, McPherson and HammondRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Heresy of Heresies: A Defense of Christian Common-Sense RealismFrom EverandThe Heresy of Heresies: A Defense of Christian Common-Sense RealismNo ratings yet

- Secularization Thesis DebateDocument5 pagesSecularization Thesis Debatexgkeiiygg100% (2)

- Is Critique Possible in The Study of Lived Religion Anthropological and Feminist ReflectionsDocument19 pagesIs Critique Possible in The Study of Lived Religion Anthropological and Feminist ReflectionsAlberto Bernardino OhacoNo ratings yet

- The Spirit and the Common Good: Shared Flourishing in the Image of GodFrom EverandThe Spirit and the Common Good: Shared Flourishing in the Image of GodNo ratings yet

- (Published in Association With Theory, Culture & Society) Peter Beyer - Religion and Globalization-SAGE Publications LTD (1994)Document258 pages(Published in Association With Theory, Culture & Society) Peter Beyer - Religion and Globalization-SAGE Publications LTD (1994)pujaalvianadewantriNo ratings yet

- A Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyFrom EverandA Living Tradition: Catholic Social Doctrine and Holy See DiplomacyNo ratings yet

- Jesus and Structural ViolenceDocument305 pagesJesus and Structural Violencedavid100% (1)

- Report On Reading Program For Bulawanong SuloDocument3 pagesReport On Reading Program For Bulawanong SuloSsbf Budong Mordeno Japson100% (1)

- Report of UsDocument7 pagesReport of UsMd Usman KhanNo ratings yet

- BCL and Mjur Prize List 2016 0Document5 pagesBCL and Mjur Prize List 2016 0Randy PongtikuNo ratings yet

- NITDocument124 pagesNITNilesh YNo ratings yet

- Q3 Computer System Servicing - Grade 9Document11 pagesQ3 Computer System Servicing - Grade 9Yeshamae JimenezNo ratings yet

- LP Basic Categories of Words 1Document8 pagesLP Basic Categories of Words 1Ronnie ValderamaNo ratings yet

- Science 10 Biology Unit Assessment PlanDocument10 pagesScience 10 Biology Unit Assessment Planapi-359145589No ratings yet

- UNIT 3 - Professional DevelopmentDocument7 pagesUNIT 3 - Professional DevelopmentNguyen Xuan Nam (FGW HCM)No ratings yet

- Precede Proceed Model by Lawrence W. GreenDocument3 pagesPrecede Proceed Model by Lawrence W. GreenmadamcloudnineNo ratings yet

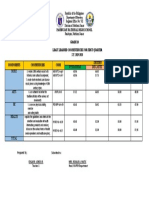

- Print Least Learned CompetenciesDocument1 pagePrint Least Learned CompetenciesBen ZerepNo ratings yet

- Autism PamphletDocument2 pagesAutism Pamphletapi-238810328No ratings yet

- LXP RFP For L&D TransformationDocument24 pagesLXP RFP For L&D Transformationnana hariNo ratings yet

- Majestic Interview CallDocument7 pagesMajestic Interview CallAbrar Hussain KhanNo ratings yet

- Software Testing StrategyDocument38 pagesSoftware Testing Strategyapi-3738458100% (1)

- Class 11 Economic Competency Based Question Chapter-Collection of DataDocument18 pagesClass 11 Economic Competency Based Question Chapter-Collection of DataKabri VagelaNo ratings yet

- Bliss The Eclipse and Rehabilitation of JJR Macleod, Scotland's Insulin LaureateDocument8 pagesBliss The Eclipse and Rehabilitation of JJR Macleod, Scotland's Insulin LaureateCarmen ZavalaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan2 2Document8 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan2 2Robelyn TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Important Questions 18ME55 FPE (1) PDFDocument8 pagesImportant Questions 18ME55 FPE (1) PDFRoman EmpireNo ratings yet

- Story Book ConverterDocument6 pagesStory Book ConverterInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Master Prospectus 2020Document90 pagesMaster Prospectus 2020Fatima JahangirNo ratings yet

- Greetings: Jorielene Junio Sharmaine Escalona Plese Affix Yur Signature in Our Attendance SheetDocument8 pagesGreetings: Jorielene Junio Sharmaine Escalona Plese Affix Yur Signature in Our Attendance SheetAbe Espinosa100% (1)

- APA - DSM 5 Intellectual Disability PDFDocument2 pagesAPA - DSM 5 Intellectual Disability PDFEmil Mari FollosoNo ratings yet

- Teacher Appraisal Summary: Teaching Standards RatingsDocument2 pagesTeacher Appraisal Summary: Teaching Standards RatingsKevinNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 Instruction 203Document3 pagesAssignment 3 Instruction 203api-612070235No ratings yet

- Submitted By: Timothy Domingo Arvin Emata Kaer Mercado Gerald Bengco Mikko BermudoDocument11 pagesSubmitted By: Timothy Domingo Arvin Emata Kaer Mercado Gerald Bengco Mikko BermudoKaren ManaloNo ratings yet

- CV GB DanielaRibeiroDocument2 pagesCV GB DanielaRibeiroDanielaRibeiroNo ratings yet

A Kairos Moment for Public Theology by William F Storrrar

A Kairos Moment for Public Theology by William F Storrrar

Uploaded by

biju.josephCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Kairos Moment for Public Theology by William F Storrrar

A Kairos Moment for Public Theology by William F Storrrar

Uploaded by

biju.josephCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 www.brill.

nl/ijpt

2007: A Kairos Moment for Public Theology

William Storrar

Center of Theological Inquiry, Princeton

Abstract

The simultaneous launch of the International Journal of Public Theology and its spon-

soring Global Network for Public Theology represents a ‘kairos’ moment of opportunity

for theologians and other scholars working in the emerging field of interdisciplinary

theological inquiry into contemporary public issues. Such moments happen, this arti-

cle argues, when a disruptive social experience calls for the response of collaborative

theological inquiry into the public issues generated by such disruptions. By telling an

autobiographical story of a public theologian and by reflecting on the history of the

pioneering Edinburgh University Centre for Theology and Public Issues, the article

identifies common factors that have led a growing number of scholars and research

centres around the world to identify with the phrase ‘public theology’. Such factors

include a commitment to the ecclesial and the emancipatory dimensions of doing

theology and employing research methods that include the marginalized as agents of

social transformation.

Keywords

disruptive experience, collaborative research, globalization, public sphere.

This is an extraordinary moment for those of us who have been engaged in

theological reflection on public issues around the world in recent decades. With

the launch of the International Journal of Public Theology and the Global Net-

work for Public Theology in 2007, we may speak of this year as a ‘kairos’ moment

for this emerging research field. It is the right time to reflect on the factors that

have led to this convergence of theological interest. It is an opportune moment

to consider the nature of our conversation and its potential for bearing fruit. As

the chair of the journal’s editorial board, a past and present director of research

centres in the Global Network, and the host of its first meetings, it is perhaps

incumbent on me to help start that conversation in this article.

© Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2007 DOI: 10.1163/156973207X194457

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 5 3/29/07 7:05:40 PM

6 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

I shall begin with an account of my own story as a public theologian. All of

us come to this converging global conversation about public theology from

our own involvement with public affairs in the places where we live and work:

in my case, until recently, Scotland. That personal experience has both shaped

my understanding of public theology and prompted an openness and com-

mitment to this wider international collaboration. After telling this personal

story of my own journey towards an identity and calling as a public theolo-

gian, I shall reflect on the local story of the Centre for Theology and Public

Issues at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Under its visionary founder

Duncan Forrester, CTPI, as it is commonly known, was one of the pioneering

research centres in the field of public theology in the 1980s and 1990s. I had

the privilege of leading the Centre from 2000 to 2005, in a time of transition.

Out of that experience, the idea of a global network for public theology was

first conceived in conversation with fellow public theologians around the

world. The telling of this global story will lead me to set out some concluding

reasons why I think this is indeed a kairos moment for public theology, from

my new perspective as the director of the Center of Theological Inquiry (CTI)

in Princeton.

Let me first offer a brief, opening definition of public theology that both

emerges from and shapes these three narratives, personal, local and global:

I understand public theology to be a collaborative exercise in theological

reflection on public issues which is prompted by disruptive social experiences

that call for our thoughtful and faithful response.1 Those familiar with my

own academic discipline of practical theology will recognize that I am drawing

on the pastoral cycle method of practical theological reflection, which also

begins its work with those interruptions to the routine of our lives—conflict,

suffering, death—that demand an explanation and pastoral response.2 Allow

me then to give such an account of public theology in terms of three critical

disruptive experiences.

A Personal Story: The Collapse of Christendom

My first disruptive social experience on the way to becoming a public theolo-

gian in the west was living through the final collapse of Christendom in

1)

On the collaborative nature of public theology, see David F. Ford, Theology: A Very Short Intro-

duction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 174-5.

2)

Paul Ballard and John Pritchard, Practical Theology in Action, 2nd edn (London: SPCK, 2006),

p. 85.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 6 3/29/07 7:05:40 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 7

Britain. I am a cradle Christian, born and baptized into a Christian society. In

the village where I grew up in the Scotland of the 1950s and early 1960s, my

Christian formation was the daily responsibility not only of my family and

church, but also the local school and community, the media and the wider

society. I sang the same hymns, absorbed the same Christian values, heard the

same biblical allusions and worshipped the same God in all these spheres of

my young life: in my mother’s daily piety and weekly churchgoing with her

children; in my school teacher’s morning prayers and Bible stories with her

class; at my Scout troop’s wreath laying ceremony at the village war memorial;

and in the seamless mixing of hymns and popular songs on children’s radio

programmes. There was even an implicit public theology being taught and

imbibed throughout this childhood. Every week, uniformed and alert in the

Scout hall, we promised to do our duty to God and the Queen. At the end of

every visit to the cinema, we stood to sing ‘God Save the Queen’. This was not

a fundamentalist or even an evangelical upbringing. It was a comfortable but

sincere post-war marriage of Protestant Christianity and late modernity; but,

divorce was imminent.

This integral, conservative Christian world was swept away by the liberal-

ization of British society in the 1960s, on a wave of economic affluence, con-

sumerism and its accompanying youth and leisure culture. For most of my

own contemporaries in Scotland and Britain, this cultural sea-change meant a

growing indifference to a church that represented the restrictive and even

authoritarian and hypocritical moral values of the 1950s. What had been a

perfect marriage between church and culture in that decade, quickly became

grounds for divorce among the next generation, coming of age in the 1960s

and 1970s and seeking a new freedom from the old restraints of family, church

and social deference. This generational abandonment of institutional religion

can be traced in the numerical decline of the mainline American denomina-

tions as well as the historic state churches of Europe by the 1970s. But what

was my response to this collapse?

The social historian Callum Brown has named the year 1963 as the notional

date to mark the sudden ‘death of Christian Britain’, after its flourishing in the

post-war period, between 1945 and the late 1950s. His explanation of this

sudden collapse focuses on the emancipation of women in these years. From

the early nineteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries women were seen as the

guardians of the faith in home and society. For generations they passed on the

Christian discourse of salvation and ensured its circulation in daily family and

community life as well as in the Church. As women led more independent

lives from the 1960s onwards, entering the workforce, higher education and

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 7 3/29/07 7:05:41 PM

8 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

the professions, they increasingly abandoned or rejected this religious dis-

course and role. The consequences for British society were sudden and dra-

matic; as Brown concludes:

It was only when that discursive power waned that secularisation could take place.

The result was not the long, inevitable religious decline of the conventional secu-

larisation story, but a remarkably sudden and culturally violent event. In the

1960s, the institutional structures of cultural traditionalism started to crumble in

Britain . . . the immediate victim was Christianity, challenged most influentially

by second-wave feminism and the recrafting of femininity.3

Across the Atlantic, the American theologians Stanley Hauerwas and William

Willimon also think of that year as the moment when their own seamless

Christian social world changed forever:

Sometime between 1960 and 1980, an old, inadequately conceived world ended

and a fresh, new world began . . . When and how did we change? Although it may

sound trivial, one of us is tempted to date the shift sometime on a Sunday evening

in 1963. Then, in Greenville, South Carolina . . . the Fox theater opened on a

Sunday . . . That evening has come to represent a watershed in the history of Chris-

tendom, South Carolina style. On that night, Greenville . . . served notice that it

would no longer be a prop for the church.4

In these two accounts of this same disruptive social experience, the end of

Christendom on both sides of the Atlantic, we see the seeds of two very

different Christian theological responses to such events.

For Hauerwas and Willimon the end of Christendom represents an exciting

opportunity to recover the true identity of the Church. Freed of its fatal com-

promise with power in the era of Christendom, and abandoning its false role

as manager of a Christian society, the Church can be now a colony of resident

aliens, bearing witness to Christ through its radical discipleship and distinc-

tive common life amid an American culture hostile to the Gospel.

Their theological response to this disruptive cultural event is an ecclesial

one. As they argue in their highly influential 1989 book, Resident Aliens, the

challenge is for the Church to reclaim its Christian language and practices as

the people of God and to rediscover its Christian calling to be the people of

3)

Callum Brown, The Death of Christian Britain (London: Routledge, 2001), pp. 175-6.

4)

Stanley Hauerwas and William Willimon, Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony (Nash-

ville: Abingdon Press, 1989), pp. 15-6.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 8 3/29/07 7:05:41 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 9

God. In these ways the Church after Christendom can offer an alternative

model of human society rather than seeking to manage its problems.

Callum Brown’s analysis as a social historian rather than as a theologian

suggests a rather different response to this disruptive experience; an emancipa-

tory rather an ecclesial one. He sees the end of Christendom as being about

emancipation for people in a restrictive society, especially women. Certainly

for me, the 1960s brought the disruptive social experience of a personal awak-

ening to the many emancipatory causes in the post-war political world. This

was the era of the civil rights and anti-war movements in America, the student

movement in France, the moral resistance of Czech dissidents to Soviet occu-

pation, and the postcolonial independence movements, civil wars, famines

and anti-apartheid struggle in Africa. Even new ideas about women’s rights,

the environmental crisis and ‘Third World’ development were dawning on

me. All the time I found myself asking how these public causes and issues at

home and abroad might relate to the Jesus of my childhood faith. I knew

enough from my Christian upbringing to think that the ethics of this Jesus

were radical in their implications for society and encompassed the whole of

life, not just Sundays; but how was that emancipatory connection to be made

between theology and the injustices of the world in the 1960s of my youth?5

This nagging question drew me to radical expressions of Christian disci-

pleship and spiritual practice outside the ‘ken’ of my conventional upbring-

ing in a parish and national church: the Christian pacifism and Quaker

spirituality of simplicity, equality and silence in the Society of Friends; the

militant compassion and active service to the poor found in the early history

of the Salvation Army; and the austere common life of poverty, work and

prayer in the Benedictine monastic order. All were closer to Hauerwas and

Willimon’s vision of a disciplined ecclesial response to a hostile world after

Christendom. Yet, in the end my response to the disruptive experience of the

1960s took a different turn.

A growing interest in public affairs led me to join not the Quakers, Salva-

tionists or Benedictines but more prosaically the high school debating team

and the local branch of a political party, before going on to study politics at

university in the early 1970s. This was accompanied by my involvement in

5)

On this question the Canadian Catholic theologian and ecumenist Gregory Baum notes:

‘Through an altogether unique historical development beginning in the 1960s, the emancipatory

dimension of divine redemption has assumed, for the first time, a central construction in Chris-

tian theology’, Gregory Baum, ed., The Twentieth Century: A Theological Overview (Maryknoll:

Orbis, 1999), pp. 247-8.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 9 3/29/07 7:05:41 PM

10 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

student politics and university government on the tail end of the campus rad-

icalism of the 1960s. It was during this time that I had an unexpected and

disruptive spiritual experience of emancipation that fundamentally altered my

perspective on theology and public issues.

The most momentous event of my student years was a deep, life-transforming

experience of the crucified and risen Christ in the Church’s ministry of ‘word

and sacrament’. It came about through encounter with the Student Christian

Movement and the witness of the British evangelical student movement, at an

exciting moment in its history when it emphasized the critical use of the

Christian mind and social responsibility as well as personal salvation and evan-

gelism. I suspect that for many of us in the Global Network for Public Theol-

ogy today this formative Christian experience in our student days remains a

taproot of our spiritual and intellectual commitment to a publicly engaged

theology. It is certainly so in my case, although it required a further transfor-

mative encounter with the deeply evangelical Reformed theology of my

teacher, Thomas F. Torrance, before that student evangelical taproot was firmly

planted in the sustaining ecclesial soil of Scripture and the ancient creeds, the

Reformed confessions and modern ecumenical agreements. However, it was

that student evangelical experience which led my inconstant steps as a follower

of Christ back to membership of the institutional church and eventually to a

call to the ministry of the Gospel in my own Church of Scotland. The ques-

tion remained how to connect this growing faith with public life.

My theological education for the ministry took place in the later 1970s, at

an exciting time for anyone interested in the relationship between theology

and public life. At last I was introduced to ways of connecting Christian theol-

ogy and contemporary struggles for human emancipation. It was a time when

Jürgen Moltmann’s political theology of hope and the crucified God, arising

from the disruptive experience of ‘Germany after Auschwitz’, was being

brought into critical conversation with the political Christ of the new libera-

tion theologies from Latin America, arising from ‘the irruption of the poor’

into human history, as Gustavo Gutierrez put it.6 Nevertheless, the theologies

of Moltmann and Gutierrez did not separate their emancipatory political con-

cerns from their concern for the ministry and mission or history of the Church.

Rather, they challenged us all to re-conceive them more faithfully in biblical

6)

Jürgen Moltmann, ‘Political Theology in Germany After Auschwitz’, in William F. Storrar and

Andrew R. Morton, eds, Public Theology for the 21st Century (London: T&T Clark International,

2004), pp. 37-43; Gustavo Gutiérrez, A Theology of Liberation, rev. edn (London: SCM Press,

1988), p. xx.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 10 3/29/07 7:05:41 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 11

and evangelical terms. Studies in the mission history of the Jesuits in Asia and

Latin America or the radical evangelical campaigners for slave emancipation in

America and indigenous rights in Africa brought home to me that theirs was

no new voice in the Church.7

What was happening here, of course, was that the collapsed Protestant

world of my childhood was being repaired as a new ecumenical cosmos. I was

learning to live in a larger religious and public world of meaning, with a grow-

ing sense of the ecumenically rich fabric of global Christianity. Again, I sus-

pect that I am not alone in that journey of faith. Many of us in mid-life within

the Global Network have come to our commitment to a global public theol-

ogy through this disruptive and reparative experience of both evangelical and

ecumenical conversion to the Gospel, the Church and the world. Our response

to the disruptive social experience of the collapse of Christendom, in its west-

ern or postcolonial or apartheid forms, has been to seek a public theology that

is both ecclesial and emancipatory. Again, for many of us, our commitment to

holding together both the ecclesial and the emancipatory dimensions of pub-

lic theology has found its most helpful articulation in the work of the late

South African missiologist and anti-apartheid theologian David Bosch. In his

seminal book, Transforming Mission, he offers an integrative ecumenical and

postmodern paradigm of mission that seeks to hold together all aspects of the

triune God’s mission to the world in creative tension.8

Inspired by that kind of Reformed and ecumenical vision, I answered a

congregational call to serve as a local parish minister in an area of declining

heavy industry and high unemployment in the west of Scotland in the 1980s.

My members were among the last workers and managers in the last steel mill

in Scotland, before it too closed. There, I was humbled time and again by the

exceptional public witness and costly service of ordinary church members;

they cared quietly for their vulnerable neighbours; they worked unseen for

justice and reconciliation across the sectarian divide of Catholic and Protes-

tant in their local community; they tirelessly raised money and awareness on

issues of poverty in the wider world; and all of this was inseparable from their

life of worship and prayer and their faith in Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord.

When I became a university teacher of practical theology in the 1990s, I saw

the same willingness in my best students to live out the radical implications of

7)

Andrew C. Ross, A Vision Betrayed: The Jesuits in Japan and China 1542-1742 (Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press, 1994); and John Philip (1775-1781): Missions, Race and Politics in

South Africa (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1986).

8)

David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll:

Orbis, 1991), pp. 368-510.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 11 3/29/07 7:05:41 PM

12 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

their faith and studies. Years later, for example, I discovered that one former

student was living and working as a Baptist minister with her husband and

young family in one of Britain’s poorest urban communities. Unknown to me

at the time, the challenge of writing an essay on liberation theology in one of

my classes had set her on this sacrificial path of service. Such students are far

above their teacher.

This disruptive experience of ministry in a local church and of teaching in

the context of theological education for ministry was formative in my under-

standing of public theology. Hauerwas and Willimon are right—such a theol-

ogy must be rooted in the common life and public witness of the local church.

Public theologians need to learn from congregational pastors and members as

they seek to be faithful witnesses to Jesus Christ in their communities; but

public theology must also be rooted in the academy, whether in a university,

college or seminary setting. It is vital that we engage in the critical study of

biblical and theological texts that challenge our own narrow interests, includ-

ing ecclesial interests, and give us a larger grasp of the mind and mission of

Christ. Such theological work on public issues in the Church and academy

requires other perspectives to understand the human social condition; and so

we are also committed to interdisciplinary study and dialogue with colleagues

in other branches of knowledge, everything from economics and ecology to

philosophy and psychology.

The work of local ministry in the congregation and the work of academic

study in the classroom are therefore two key sites for doing public theology. It

is here that we experience the disruptive solidarity of suffering with our neigh-

bours and learning with our students. It is here that we are in conversation

with viewpoints that challenge and bring into question our unexamined prej-

udices about faith, politics and life. I know these have been formative experi-

ences for many of us in the Global Network. We therefore need to keep the

congregation and classroom at the heart of our collaboration in doing public

theology, keeping alert to the emancipatory potential of both as ‘truth-seeking

communities’.9

However, my understanding and practice of public theology have been

shaped also by wider publics than those of the local church or university class-

room. Through engagement with our churches and politics at the national and

international level, many of us have learned both the severe limits and the

surprising opportunities of institutional public engagement for theologians.

9)

I am indebted to two colleagues in the Center of Theological Inquiry, John Polkinghorne and

Michael Welker, for introducing me to this helpful phrase.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 12 3/29/07 7:05:42 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 13

As a member of the Church of Scotland’s General Assembly committees

and boards, I participated in working groups and church reports on a range of

issues—medical ethics, the government of Scotland, the future of ministry—

reflecting the distinctive Reformed vision of Christ’s lordship over all aspects

of church and society. Despite valuable work done, the experience left me

wondering whether years of service by theologians in producing such official

reports have any lasting impact on the life of the Church or its witness to

the world. In reflecting on the risks of institutional involvement for theolo-

gians, I am reminded of the Anglican theologian and Scottish moral philoso-

pher Donald MacKinnon’s scorching remarks, in his essay on ‘Kenosis and

Establishment’:

The young Christian in the academic world . . . can easily be blind to the sort of

abuse of genuine talent encouraged by ecclesiastical and quasi-ecclesiastical insti-

tutions . . . Men and women are taken from their proper, fundamental profes-

sional work and the resources of their gifts mercilessly exploited in order that the

Christian cause can be commended . . . There is a characteristically Christian phi-

listine disdain here for disinterested concern with the truth for its own sake . . .

and there is a graver pastoral irresponsibility in that the lasting spiritual damage

which is done to individuals in this way is often completely overlooked until it is

too late.10

This suspicion was raised even more acutely for me by the experience of taking

on a formal institutional leadership role in the national church: convening the

General Assembly’s Board of Ministry from 2000-2002. During that time we

successfully delivered new policies on the vocational profile, selection and sti-

pends of ministers, based on the work of a theological study group on the

future of ordained ministry that I had already led for the Board. Circumstances

demanded that we also conduct a review of the Board’s internal administrative

structures and ways of working in line with that same Reformed theological

vision and a more postmodern approach to organizational culture and ethics.

In the event, the theologically informed administrative reforms that the Board

unanimously agreed offended certain established interests in the church and

met with fierce opposition from prominent figures in the General Assembly.

After having had to defend them as the Board convener in a long debate on the

floor of the Assembly, the changes were vindicated in the final vote and subse-

quently implemented. Within a few years, however, such carefully reasoned

10)

Donald MacKinnon, The Stripping of the Altars (Collins: Glasgow, 1969), pp. 27-8.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 13 3/29/07 7:05:42 PM

14 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

and hard won reforms were lost amid the crisis of financial cutbacks and the

vortex of reorganization affecting so many reeling central bureaucracies in the

declining mainline churches today.

Other members of the Global Network also bring this senior level of

experience in institutional church leadership to the work of doing public the-

ology, whether in a denominational or ecumenical context. This too must

become part of our conversation on doing public theology. We are launching

a new journal and research network at a time when many regard the ecu-

menical movement to have lost its way, when the historic western Catholic

and Protestant churches are retrenching and caught in divisive internal debates,

and when the global majority of Christianity has shifted to the south and been

transfigured by Pentecostalism, Evangelicalism and other indigenous Chris-

tian movements. It is a matter of urgency that the international journal and

Global Network give thought to identifying and supporting the new loci of

public intellectual renewal for the global Church; including their own part in

that endeavour.

In stark contrast to my experience of the institutional politics of the national

church, when I joined with fellow citizens in practising a postmodern style of

institutional reform in Scottish public life, our approach clearly resonated

with the national mood and led on to lasting constitutional changes. With

suitable irony, this secular and pluralist political movement, launched in 1988

with a Constitutional Convention, was quite open to a critical retrieval of

Scottish theological traditions in support of its cause, as articulated in a 1989

Church of Scotland report on the government of Scotland; while the Kirk’s

later approach to internal reform launched in 2001 seemed to me set on

abandoning the self-critical and explanatory power of its own Reformed theol-

ogical memory for the sake of typically modern institutional interests and

evangelical fashions.

In these circumstances, my theologically shaped public concern found more

constructive and fruitful expression within Scottish civil society in the 1990s,

as an active member of the civic democratic movement for Scottish self-

government. As the chair of Common Cause, a national civic forum on dem-

ocratic renewal, I worked closely with secular intellectuals, cultural artists and

civic leaders to make the democratic case for constitutional reform across the

party political divide. We were a small but, on occasion, influential part of a

much broader civic coalition for democracy that included the trade unions,

the churches, the political parties, the voluntary sector and campaigning

groups. This style of participatory politics was ultimately successful with the

establishment of the new Scottish Parliament in 1999, after the resounding

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 14 3/29/07 7:05:42 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 15

1997 referendum vote by the Scottish people in favour of a legislature for

Scottish affairs with fiscal powers.

To give an example of the postmodern politics in which we were engaged in

Common Cause and the wider civic movement: during the closing days of the

referendum campaign in September 1997, I organized a tour round small

town Scotland by a travelling caravan of mainly secular Scottish writers and

musicians, poets and artists, joined en route by church and political leaders.

We held public forums and cultural celebrations in church halls, town halls,

school and university halls from the Scottish north east and Highlands to the

lowland Borders; encouraging honest, serious, open discussion of people’s

hopes for the future, rather than partisan debate, as they prepared to vote in

the referendum. We called our little touring group ‘the Bus Party’ in homage

to our battered mode of transport and out of our concern to transcend party

political differences in this common cause of democratic renewal. The Church

was present in this bus party and wherever it stopped, as a host offering hospi-

tality for public conversation, whether in a poor urban community or prosper-

ous country town, and as a listener offering careful attention to the aspirations

of young people and adults who felt far from the centres of power in Edin-

burgh or London. This postmodern mode of public engagement may seem

removed from the fiery pulpit of John Knox, denouncing an idolatrous reign-

ing monarch, but it manifests the same Reformed spirit of public responsibil-

ity, not least for the educated wellbeing of people in every place, especially

those on the margins.

Secular academic commentators on these recent political developments in

Scotland have since recognized that Reformed theological arguments on pop-

ular sovereignty and the limits of power played a not insignificant role in shap-

ing Scottish public thinking on constitutional reform. They have also noted

the critical role of civil society organizations, including the churches, in the

cross-party political movement for self-government that led to the democratic

recall of the Scottish Parliament almost three hundred years after its adjourn-

ment in 1707.11 Hence, 2007 is an opportune moment to remember this

11)

See Lindsay Paterson, ‘Scottish Social Democracy and Blairism: Difference, Diversity and

Community’, in Gerry Hassan and Chris Warhurst, eds, Tomorrow’s Scotland (London: Law-

rence and Wishart, 2002), pp. 116-29 at p. 119: ‘The same kinds of communitarian principles

were generalised in the constitutional debates from 1988 onwards. One of the most striking

features of these discussions, compared to the 1970s, was the interest in sovereignty and the

emerging conclusion that Scottish ideas about legitimate government rested on the principle of

popular sovereignty. Again the religious origins are unmistakable, and indeed Church of Scot-

land theologians in particular were eloquent in their contribution to the debate, modernising

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 15 3/29/07 7:05:42 PM

16 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

contemporary Scottish case study of theological engagement in public life and

the postmodern politics of civic networking and participatory democracy. It

reminds me that it is still possible, even in the secular, pluralist west, for

churches and theologians to influence political change in a democracy, if we

are willing to do so as one modest voice among many in a pluralist public

sphere and as one civic partner among many in a pluralist civil society. Again,

my hunch is that many of the theologians in the Global Network and contrib-

uting to the International Journal of Public Theology will be those who have had

similar experiences of articulating public theological ideas in appropriate ways

within participatory democracy and civil dialogue in the public sphere in their

own contexts. We need to learn from these local insights as we seek ways of

participating in the global public sphere.

This Scotland of the 1997 Referendum was a long way from the homoge-

neous Christian society of Protestant, Unionist Britain that was established in

1707 and which I grew up in during the 1950s. My journey from that child-

hood in the twilight of an imperial power to mid-life civic involvement in the

public affairs of a small democracy in an interdependent world has been both

a theological adventure and a public odyssey. It has shaped my own under-

standing of public theology and my reading of the kairos moment that we

now face with the launch of the International Journal of Public Theology and

the Global Network for Public Theology. Colleagues in the Global Network

have faced their own disruptive political experiences in this period: living in

post-apartheid South Africa and building a non-racial democracy there; or

adjusting to post-colonial rule in Hong Kong; or helping to restore demo-

cratic governance in Brazil; or working for reconciliation in Northern Ireland

or Indonesia. These personal stories challenge us to reflect now together on the

common and yet very diverse experiences we have had of doing public theol-

ogy in different parts of the world.

This leaves me wondering whether the following experiences will resonate

with colleagues in the Global Network to such a degree that we may speak of

a shared sense of what it means to be public theologians: engaging in the

politics of democratic transformation and not simply in the politics of protest

and prophetic resistance; participating in the public sphere with the civility to

strangers and attentiveness to their opinions that this requires of active and

the Knoxian idea that the people have the right to overthrow unjust rulers. Sovereignty, they

argued, is intrinsically limited. Federalism is not just a way of organising a constitution, but a

principle based on human fallibility. Because we have a duty to respect our fellow human beings,

governments should seek to share power, not to monopolise it.’

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 16 3/29/07 7:05:43 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 17

responsible citizens; wrestling with the institutional forms of the Church and

its public witness as it seeks to be faithful to the Gospel and engaged with its

cultural context. These experiences have certainly shaped my own understand-

ing of the public nature of theology.

When I was appointed to the Chair of Christian Ethics and Practical Theol-

ogy at the University of Edinburgh in 2000, I sensed it was time to bring

together the threads of these thirty years and more of personal engagement

with public issues. A growing awareness of the international radicalism of the

1960s had left me with a sense of the power of ordinary people to organize and

campaign for emancipatory change but also with a lingering question of how

that related to the emancipatory teachings of Jesus of Nazareth and my cradle

faith in God. In the 1970s my involvement in student politics and renewed

experience of Christ in the Church had shown me that living institutions like

universities and churches can both be changed and be the agents of change.

Adult responsibility as a parish minister, university teacher and active citizen

in the 1980s and 1990s had taught me to recognize the Holy Spirit at work

in the public-spirited, Christ-like lives of others, even beyond the boundaries

of the Church and Christian faith. Institutional leadership experience had

further taught me to recognize with Reinhold Niebuhr the demonic power of

human sin, spiritual evil, group interests and organizational pathologies in

corporate life and the moral power of individuals to resist such forces.12

By 2000, it was time for me to develop a more adequate theology of public

engagement in the context not of imperial Britain or autonomous Scotland

but of a globalizing world. As a stimulus to that theological reflection, I had

the privilege of becoming the director of the University of Edinburgh’s well-

known Centre for Theology and Public Issues, founded by Duncan Forrester

in 1984. He is one of the great, later twentieth century pioneers of an ecu-

menical and engaged public theology. It is significant that he chose to express

his public theological vision in the collaborative work of a university research

centre for theology and public issues and to found it at the time he did. This

is the second story I wish to tell in making sense of our present kairos moment:

the institutional story of CTPI and the disruptive social experience which led

to its birth.

12)

Reinhold Niebuhr, Moral Man and Immoral Society (New York: Scribner, 1960).

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 17 3/29/07 7:05:43 PM

18 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

A Local Story: The Collapse of the Post-War Consensus

At CTPI in the 1980s and 1990s, Forrester developed a deliberate and distinc-

tive approach to doing public theology. The Centre’s method was to begin

with a current public issue that was discerned to be important to the public

welfare and where theology might make a constructive contribution to its

analysis and resolution. A group of theologians, research scholars in other dis-

ciplines (often from the social sciences), public policy makers and practitio-

ners in the field under review, would then be brought together for a sustained

conversation and period of research, writing and public discussion on the issue

in question. Up to this point, the method employed by Forrester and CTPI

was not markedly different from that of its ecumenical antecedents in the Life

and Work movement and Moot meetings of the 1930s; where J. H. Oldham

and other ecumenical pioneers of the World Council of Churches gathered

together similar groups of experts to consider public issues.13 However, For-

rester introduced a further partner to this classic interdisciplinary method in

ecumenical social ethics that made his approach radically different and of

momentous consequence for the development of public theology as it is

understood today in the new International Journal of Public Theology and the

Global Network. He insisted that the presence and voice of those most affected

by the public issue under scrutiny be welcomed and heard for their expert

opinion in the research process, alongside those of the theologians, social sci-

entists, policy makers and practitioners: ‘We must never talk about the poor

behind their back’, he famously declared and courageously practised. For

example, CTPI’s discussions on poverty and the future of welfare, a hot topic

in Thatcher’s Britain in the 1980s, took place in poor public housing com-

munities with local people as the hosts and expert contributors. Angry voices

were often heard in the university conferences CTPI held under his direction,

as people whose lives were a daily struggle for survival expressed their frustra-

tion at the detachment and veiling of their problems in the academic analysis

offered by even the most socially concerned and empathetic theologians, social

scientists or policy makers.

What led Forrester to develop this innovative method in doing theological

research on public issues? I think that at least three influences prompted his

welcome to the poor, the marginal and vulnerable as expert partners and col-

leagues in the work of CTPI: his early encounter with the human face of

poverty and the caste system as a young educational missionary in India; his

13)

See Graeme Smith, Oxford 1937: The Universal Christian Council for Life and Work Confer-

ence (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2004).

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 18 3/29/07 7:05:43 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 19

early openness as a teacher of politics, Christian ethics and practical theology

to Latin American liberation theology and the challenge it represented to the

western Church, its ecclesiology, ethics and mission; and the early apprecia-

tion he had of his theologically orthodox and evangelical Scottish Reformed

tradition, with its political radicalism and egalitarian spirit resonating from

John Knox in the mid-sixteenth century down to his own close relative, John

Baillie in the mid-twentieth century.14 This radical spirit served Forrester well

in the turbulent political years of the 1980s in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain. It

enabled him to respond to the disruptive social experience of the collapse of

the post-war political consensus on the economy and social welfare by found-

ing the Centre for Theology and Public Issues to address its consequences for

the churches and society.

This Centre became one of the leading places in Britain during the Thatcher

and post-Thatcher era to conduct an ecumenical discussion, cross-disciplinary

analysis and public-spirited debate on the big public issues of that era: from

welfare reform and income distribution in a neo-liberal economy to interna-

tional security at the end of the Cold War and progressive politics after

socialism. Many secular British academic scholars and policymakers found an

intellectual, moral and even spiritual home in CTPI’s working groups and

conferences in this period. Through the Centre’s programmes, they could

express a common alienation from regimes and policies that mocked the post-

war consensus on low unemployment, social welfare, public services and inter-

national cooperation, as well as seeking to articulate an alternative vision and

policy framework. CTPI was a labour of love, typically run on a shoestring

with small grants from private foundations, enormous industry by its gifted

and dedicated staff and large amounts of free intellectual labour from its

mainly volunteer researchers and speakers at its famous weekend conferences.

Outstanding work was done in this period, including serious and well-funded

research, making a recognized theological contribution to public debate and

14)

See Duncan B. Forrester, On Human Worth (London: SCM Press, 2001) for an account of

his Indian experience; Theology and Politics (Oxford: Blackwell, 1988) for his appreciation of the

insights of liberation theology; and Truthful Action (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) for his

identification with the Scottish Reformed tradition of politically radical orthodoxy. See also his

essay, ‘The Political Service of Theology in Scotland’, in William Storrar and Peter Donald, eds,

God in Society: Doing Social Theology in Scotland Today (Edinburgh: Saint Andrew Press, 2003),

pp. 83-121, for his own reflection on this method; and my essay on his approach to public theol-

ogy, ‘Where the Local and the Global Meet: Duncan Forrester’s Glocal Public Theology and

Scottish Political Context’, in Storrar and Morton, eds, Public Theology for the 21st Century,

pp. 405-30.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 19 3/29/07 7:05:43 PM

20 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

policy. However, by the time I became director in 2000, both the political and

the academic situations in Britain had changed, requiring a review of the Cen-

tre’s approach to doing public theology.

First, the national and international political landscape had altered percep-

tibly by 2000, compared with 1984. With the election of a Labour govern-

ment in Britain in 1997, there was a real sense of moving into a post-Thatcher

era. Blair and his ‘New Labour’ party and government presented themselves as

practising a progressive ‘Third Way’ politics and non-ideological approach to

national and global governance after the fall of Communism, leaving behind

the old party divisions of left and right as outdated and irrelevant to the times.

This was all rather different from the crusading neo-liberal rhetoric and height-

ened Cold War atmosphere in which CTPI had been born and initially pur-

sued its work in the mid-1980s. However, the hopeful approach to international

affairs launched in 1997, promising an ethical foreign policy and debt relief

for the poorest nations, was overtaken by the terrible events of 11 September

2001, ushering in an era of global terrorism, regional wars and national secu-

rity regimes, and a period of heightened tension between Islamic countries

and the more secular west.

The Centre therefore had to respond to a very different framework for

addressing public issues in Britain: the politics of the Third Way with its

emphasis on the vital role of active citizenship, social capital and a strong civil

society in addressing social problems and delivering policies and resources in

partnership with government and the market. Indeed, CTPI found itself

uniquely placed to conduct research and engage in a public dialogue on this

changed approach to government in the first years of the new millennium.

The new Scottish Parliament made its temporary home from 1999 to 2004 in

the Church of Scotland’s General Assembly Hall in Edinburgh, in the same

buildings complex where the University’s School of Divinity and the Centre

for Theology and Public Issues were housed. A 2001 CTPI study on e-democ-

racy in the fledging Parliament, for example, was made easier by the ready

access our researcher had to the Scottish government ministers, members of

parliament and their staff literally standing on our doorstep. In 2004 the

Centre won a Scottish government research contract to study the attitudes of

Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Christian, Jewish and other faith communities to local

government and its service provision in Glasgow, prior to the appointment of

an inter-faith officer for the city. CTPI’s 2005 conference on global civil soci-

ety also received support from the Scottish Executive’s international affairs

unit in running a workshop on its new development partnership with Malawi

on public health programmes and HIV-AIDS treatment in both countries.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 20 3/29/07 7:05:44 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 21

This all made for a more direct and closer relationship to government for

CTPI after 1999; one that was very different from the distant and prophetic

relationship with the Thatcher and Major governments that CTPI was known

for in the 1980s and 1990s. The altered situation was not without its own

ethical dilemmas for a research centre concerned with academic independence

as well as influence on public policy. It did, however, highlight the changed

contours of the political landscape for the Centre in the opening decade of the

new century.

CTPI in 2000 also faced a changing academic environment, with the intro-

duction of the Research Assessment Exercise for all subject areas in British

universities. This required all research-active academic staff to produce a regu-

lar portfolio of their published work for peer assessment and national ranking.

With these additional pressures, the Centre could no longer expect friendly

theologians and interdisciplinary colleagues to contribute their precious

research time to work on its behalf, as in the past, without greater funding

support and publishing recognition. It became imperative to pursue research

projects that could be considered and assessed under this new research regime

in the British universities. CTPI’s future as a fully-fledged university research

institution, rather than as a semi-autonomous, church-related, part-time

think tank, depended on adapting to the increasingly demanding university

research climate.

In fact, CTPI’s story in these years was only a small part of a much larger

disruptive experience facing the academic world: the experience of globaliza-

tion in all its forms, benign and malign, complex and ambiguous. Increas-

ingly, national universities had to measure themselves on an international

scale, in a global educational market for higher education. This in turn was

only one dimension of globalization’s impact on local economies, communities

and cultures around the world in the opening years of the twenty-first century.

It was once more out of a disruptive social experience that a new approach to

doing public theology was conceived and brought to birth at CTPI.

A Global Story: The Convergence of the World

The work of the Centre of Theology and Public Issues from 2000 had to

respond to the global environment, with its storm clouds of fear about an

impending clash of civilizations, the ominous return of furious, fundamental-

ist religion to the centre stage of world affairs, and increasingly alarmist warn-

ings about global warming caused by the planet’s addiction to burning oil to

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 21 3/29/07 7:05:44 PM

22 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

fuel its globalizing economy. I had to deliver my inaugural lecture as professor

and centre director within days of the destruction of the Twin Towers in Sep-

tember 2001. I chose to speak on ministry and the renewal of public life in

that terrible and sobering global context. This concern led me to work closely

with university colleagues in other disciplines, not least in Islamic studies, to

seek external research grant funding for an interdisciplinary research pro-

gramme on the ethics of global civil society from Christian, Muslim and secu-

lar perspectives. It was designed to include collaborative research partnerships

with many of the institutions around the world now represented in the Global

Network for Public Theology. Exchange visits with colleagues planning cen-

tres for public theology in this period were formative in developing this vision

for collaborative research. I was especially grateful to Nico Koopman at Stel-

lenbosch University, leading the new Beyers Naude Centre for Public Theol-

ogy in South Africa; to Elaine Graham at Manchester University, preparing to

establish the Manchester Centre for Public Theology in the UK; and to Clive

Pearson and James Haire from Charles Sturt University, about to found PACT,

a new centre for public and contextual theology in Australia. Together and

with other colleagues in Europe, Africa, Asia, Latin America and North Amer-

ica, we began to discuss and plan a more cooperative approach to theological

research on global issues.

An international and interdisciplinary conference on the ethics of global

civil society in September 2005 was therefore not only the culmination of my

own research programme as director of CTPI, it also provided the occasion for

the directors of these research centres and graduate programmes for public

theology emerging around the world to meet together for the first time as a

group. The consultation established the strong support for new collaborative

research partnerships in a global network for public theology. It also high-

lighted the common experience of the participants that the local public issues

they were addressing in their part of the world—at Manchester, York and

Edinburgh in the UK, and in Ireland, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, South

Africa, India, Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, Canada and the USA—also had

a global dimension. The disruptive social experience of globalization in our

various contexts proved to be the catalyst for this new approach to collabora-

tive theological reflection on public issues.

This was certainly our experience at CTPI and in Scotland. The Centre

worked on a range of public issues during my five years at Edinburgh that

reflected this changing political and academic landscape. Together they con-

tributed to an evolving research agenda that focused on local and global citi-

zenship and civil society. We could not consider the question of children’s

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 22 3/29/07 7:05:44 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 23

rights and the churches in Britain, for example, except in the global context of

the UN Convention.15 As we invited a group of distinguished theologians and

ethicists from around the world to reflect on the character and challenges of

doing public theology in the new millennium, the question of globalization’s

impact on both theology and public issues proved to be a recurring theme.16

Our study of e-democracy in the Scottish Parliament could not be isolated

from the work of scholars in Canada on the impact of the internet on social

networks and public participation in the political process there.17 Research

questions that we raised about the problematic role of ethnic identity in the

civil societies of Scotland and Northern Ireland required wider comparisons

with local civil society research around the world. Our work with educational-

ists on citizenship education in Scottish schools prompted us to ask whether

we also needed to be prepared to live as global citizens in an emerging global

civil society. Our studies of immigrant faith communities in urban settings

raised research questions about multi-cultural and multi-faith living in global

cities around the world.

All of these research projects also required us to adapt our methods to con-

temporary social expectations and values, as well as to the changing political

and academic landscape. We moved away from holding weekend conferences

to disseminate our research findings, recognizing that this was increasingly

‘sacred space’ for busy families and ‘time poor’ professional people. Instead, we

organized high value day conferences in the working week that policymakers

and practitioners could attend for credit as recognized professional develop-

ment opportunities. With the expert contribution of my CTPI colleague Cece-

lia Clegg in leading the project on faith communities and urban government,

we began to develop more experience of research methods that allowed people

in a study to be co-agents of our work and research findings. We were moving

from welcoming the angry voice of the outsider in our occasional deliberations

to recognizing them as active subjects in our regular research processes.

Again, I am reflecting on this changing Edinburgh experience of conduct-

ing research on theology and public issues in order to invite similar and

15)

See the CTPI publication by Kathleen Marshall and Paul Parvis, Honouring Children: The

Human Rights of the Child in Christian Perspective (Edinburgh: Saint Andrew Press, 2004).

16)

See Storrar and Morton, eds, Public Theology for the 21st Century, pt III ‘Changing Con-

texts—Globalization’s Impact’, chs 11-14.

17)

See the essays by Barry Wellman and Keith Culver in the CTPI publication Johnston

R. McKay, ed., Netting Citizens: Exploring Citizenship in the Internet Age (Edinburgh: Saint

Andrew Press, 2004).

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 23 3/29/07 7:05:44 PM

24 W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25

comparative analyses from the research experience of colleagues around the

world. It is timely for us to address such questions of method and approach in

the new International Journal of Public Theology and the Global Network for

Public Theology. In doing so in 2007, we are all indebted to public theologians

like Duncan Forrester, whose thoughtful and faithful response to the collapse

of the post-war consensus on social welfare and international security in the

1980s was to found collaborative research institutions like CTPI that pio-

neered such imaginative and creative approaches to theological inquiry on

public issues. Others could tell similar local institutional stories from their

part of the world. The challenge now is to respond in similarly thoughtful

and faithful ways to the disruptive social experience of globalization and to

develop equally creative and imaginative collaborative approaches to theologi-

cal inquiry on global issues.

Public Theology: A Global Theological Flow

My involvement in helping to create a global research network for public the-

ology took an unexpected turn when I was invited to move to the United

States in 2005 as the new director of the Center of Theological Inquiry in

Princeton. The Center was founded in 1978 with a global and ecumenical

mission to promote advanced studies in theology across the borders of denom-

inations, disciplines, nations and religions; in order to generate fresh thinking

on the major problems of religion and society in the contemporary world.

This remit has led the Center of Theological Inquiry to address a range of

public issues in recent years, including collaborative studies on religion and

globalization and on theories of the common good. For almost thirty years

the Center of Theological Inquiry has been convening theologians and scholars

in related disciplines from around the world to hold rich interdisciplinary

conversations at the cutting edge of emerging fields of inquiry, like the dia-

logues between science and religion in the 1970s. It is therefore entirely appro-

priate that CTI should host the founding consultation of the new Global

Network for Public Theology, representing now over twenty research institu-

tions from every continent, each conducting its own set of local and interna-

tional conversations on theology and public issues.

In closing I want to suggest five reasons why our meeting in Princeton and

our launching of this new journal seem so timely and truly represent an oppor-

tune moment for global collaboration from my perspective at the Center of

Theological Inquiry. First, we all recognize that only the ecumenical fullness

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 24 3/29/07 7:05:45 PM

W. Storrar / International Journal of Public Theology 1 (2007) 5–25 25

and global breadth of the Christian tradition, in dialogue with the other great

religious traditions, can enable a faithful theological engagement with con-

temporary public issues. Secondly, we all recognize that those public issues

increasingly have both a local and a global dimension to them and therefore

require to be studied from both perspectives in collaborative research projects

around the world. Thirdly, we all recognize that such local-global public issues

are being debated by an emerging global civil society and public sphere. As

public theologians we are all committed to participating in that global public

sphere as well as critiquing the economic, social, political and environmental

disruptions of globalization. Fourthly, we all recognize that this requires us to

be dialogical and pastoral as well as analytical and prophetic in doing public

theology. The model of the single prophetic voice that characterized public

theology in the twentieth century is giving way to a more collaborative

approach to our theological task and public witness, involving faith commu-

nities and the marginalized as well as scholars and experts. Fifthly, we all wel-

come the commitment of our academic institutions around the world to

international research collaboration in all disciplines and look to the Global

Network and this journal to help make public theology a leading discipline in

this global academic enterprise.

Together, these five statements may not amount to a Princeton manifesto

for public theology in the twenty-first century, but they do give us sound rea-

sons to hope that we are witnessing, in Robert Schreiter’s happy phrase, the

launch of a new ‘global theological flow’.18 If so, then CTI will have done its

job of fostering such global and ecumenical theological inquiries and 2007

will indeed prove to be a kairos year for public theology.

18)

Robert Schreiter, The New Catholicity: Theology between the Local and the Global (Maryknoll:

Orbis, 1997), pp. 108-15.

IJPT 1,1-2_f3_5-25.indd 25 3/29/07 7:05:45 PM

You might also like

- Christian Worldview: A Student's GuideFrom EverandChristian Worldview: A Student's GuideRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Guide To The Phenomenology of ReligionDocument276 pagesGuide To The Phenomenology of ReligionLeandro Durazzo100% (2)

- The People Rizal Met During His TravelsDocument3 pagesThe People Rizal Met During His TravelsPat80% (35)

- Using The Universal Design For Learning Framework To Plan For All Students in The Classroom: Representation and Visual SupportDocument4 pagesUsing The Universal Design For Learning Framework To Plan For All Students in The Classroom: Representation and Visual SupportCorneal HarperNo ratings yet

- NARRATIVE REPORT ON StakeholdersDocument1 pageNARRATIVE REPORT ON StakeholdersMichelle Fuentes Villoso100% (2)

- A Companion To Public TheologyDocument517 pagesA Companion To Public TheologyTip Our Trip100% (2)

- Brian J. Shanley, O.P. - The Thomist Tradition (2002)Document255 pagesBrian J. Shanley, O.P. - The Thomist Tradition (2002)Caio Cézar Silva100% (1)

- O'Dea, Thomas - 5 Dilemmas in The Institutionalization of ReligionDocument13 pagesO'Dea, Thomas - 5 Dilemmas in The Institutionalization of Religionerwinjason76No ratings yet

- A Public Missiology: How Local Churches Witness to a Complex WorldFrom EverandA Public Missiology: How Local Churches Witness to a Complex WorldNo ratings yet

- EnfjDocument7 pagesEnfjleandrofransoia100% (1)

- Koopman - For God So Loved The World - Some Contours For Public TheologyDocument18 pagesKoopman - For God So Loved The World - Some Contours For Public TheologyKhegan DelportNo ratings yet

- The Mediation of the Spirit: Interventions in Practical TheologyFrom EverandThe Mediation of the Spirit: Interventions in Practical TheologyNo ratings yet

- Postmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusFrom EverandPostmodernity and Univocity: A Critical Account of Radical Orthodoxy and John Duns ScotusRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Engelke, M. Ambient FaithDocument16 pagesEngelke, M. Ambient FaithRodrigo ToniolNo ratings yet

- Missiology and the Social Sciences: Contributions, Cautions and ConclusionsFrom EverandMissiology and the Social Sciences: Contributions, Cautions and ConclusionsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Shkul 2009 Reading Ephesians PDFDocument294 pagesShkul 2009 Reading Ephesians PDFmirceapp75% (4)