Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Epidemiologia, etiologia y abordaje de la Discapacidad visual en niños

Epidemiologia, etiologia y abordaje de la Discapacidad visual en niños

Uploaded by

Florencia DominguezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Epidemiologia, etiologia y abordaje de la Discapacidad visual en niños

Epidemiologia, etiologia y abordaje de la Discapacidad visual en niños

Uploaded by

Florencia DominguezCopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 on 22 October 2013. Downloaded from http://adc.bmj.com/ on March 12, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Epidemiology, aetiology and management of visual

impairment in children

Editor’s choice

Ameenat Lola Solebo,1,2,3 Jugnoo Rahi1,2,4,5,6

Scan to access more

free content

1

MRC Centre of Epidemiology ABSTRACT circuitry develop. Newborns have an average acuity

for Child Health, UCL Institute An estimated 19 million of the world’s children are of approximately 1.5 logMAR, which rapidly

of Child Health, London, UK

2

Ulverscroft Vision Research

visually impaired, while 1.4 million are blind. Using the improves to an average acuity 0.35 logMAR by

Group, UCL Institute of Child UK as a model for high income countries, from a 24 months of age, and 0.0 (‘normal’ adult acuity)

Health, London, UK population-based incidence study, the annual cumulative by 5 years of age.1 2 Methods for assessing vision

3

Maidstone and Tunbridge incidence of severe visual impairment/blindness (SVL/BL) need to be appropriate to the age and developmen-

Wells NHS Trust, Kent is estimated to be 6/10 000 by age 15 years, with the tal stage of the child. By the age of 5 years, the

4

Great Ormond Street Hospital

NHS Foundation Trust, NIHR incidence being highest in the first year of life. The majority of (otherwise developmentally normal)

Great Ormond Street population of visually impaired children within high, children are able to comply with simple quantita-

Biomedical Research Centre, middle and lower income countries differ considerably tive shape/letter-based acuity chart testing. In

London, UK between and within countries. The numerous and mainly young, preverbal children and those with develop-

5

Institute of Ophthalmology,

University College London,

uncommon disorders which can cause impaired vision mental, cognitive or communication disorders, gaze

London, UK result in heterogeneous population which includes a behaviour responses (‘preferential-looking’) to

6

Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS substantial proportion (for SVI/BL, the majority) of graded visual stimuli can be used to give some esti-

Foundation Trust, NIHR children with additional systemic disorders or mate of acuity level.

Moorfields Biomedical impairments whose needs differ substantially from those

Research Centre, London, UK

with isolated vision impairment. Paediatricians and other Sensitive periods and amblyopia

Correspondence to paediatric professionals have a key role in early detection Animal experimental research has shown that the

Professor J Rahi, MRC Centre and multidisciplinary management to minimise the development of mammalian sensory modalities

of Epidemiology of Child impact of visual impairment (VI) in childhood.

Health, University College involves a crucial sensitive period, a time window

London Institute of Child during early development when experience has a

Health, 30 Guilford Street, profound effect on the consequent structure and

London WC1N 1EH, UK; INTRODUCTION function of the brain.3 4 Within the sensitive period

j.rahi@ucl.ac.uk Visual impairment (VI) has a significant impact on is a critical period, during which visual experience

Received 30 March 2013 the affected child’s psychological, educational and is absolutely necessary for the creation of neural

Revised 19 September 2013 socioeconomic experiences, during childhood and networks and subsequent normal function.

Accepted 24 September 2013 beyond. As the disorders which cause VI in child- Evidence from clinical (human) research supports

Published Online First hood are uncommon, the population of children the existence of this ‘critical period’ in early

22 October 2013

with VI is complex and heterogenous, but essen- infancy.5 The visual system is progressively less

tially comprises two main groups: those with iso- responsive (sensitive) until the age of about 8 years,

lated VI and those with VI in addition to, or although in some individuals sensitivity persists

associated with, another disorder or impairment. into late childhood and even occasionally into

These two populations differ significantly with adult life.4 Any disorder which prevents normal

respect to their clinical management and their visual experience will result in failure of normal

health, educational and social care needs. Here we visual development, that is, amblyopia (a form of

set out current data on frequency and causes and developmental cerebral VI). Amblyopia is treatable

the general principles of management of all-cause within the window of sensitivity, but beyond this

VI in childhood. period amblyopia is associated with permanent

impairment. In managing any ophthalmic disorder,

Normal visual development in childhood its direct visual impact and its indirect potential

Vision comprises several interconnected functions impact through amblyopia have to be considered.

such as colour vision, depth perception and higher

level cognitive functions such as visuo-spatial pro- Defining visual impairment

cessing, but the key function is acuity. Acuity is Most systems for classifying VI are based on acuity

quantified using gratings or optotype symbols such in the better eye and to a lesser degree the visual

as shapes and letters. It is now most commonly field. A child with impaired vision (of any severity)

measured on a logarithmic scale (logMAR) in in only one eye due to unilateral or asymmetric

which 0.0 is ‘normal’ acuity, and 1.0 logMAR indi- disease is thus not formally considered ‘visually

cates a 10-fold decrease in acuity (table 1). impaired’. The WHO categorisation system for VI

▸ http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ Previously, the geometric Snellen scale was more (table 1) has been very widely but not universally

archdischild-2012-301970 widely used, where 6/6 is normal vision, and 6/60 adopted. The UK criteria for the certification of

means the subject sees at a distance of 6 m the children as being sight impaired ( previously termed

symbol that would be seen at 60 m by a person ‘partially sighted’) or severely sight impaired (previ-

To cite: Solebo AL, Rahi J. with ‘normal’ vision (table 1). ously termed ‘blind’) are also set out in table 1.

Arch Dis Child Vision rapidly matures during the first few years Although children with vision better than 0.5

2014;99:375–379. of life as ocular anatomy and visual pathways logMAR but worse than 0.4 in the better seeing

Solebo AL, et al. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:375–379. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 375

Review

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 on 22 October 2013. Downloaded from http://adc.bmj.com/ on March 12, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.

eye are not formally classified as sight impaired, this level of year of life.9 The evidence on temporal trends is unclear. A

vision is below the threshold for driving and is increasingly decline in incidence of VI and SVI/BL between 1984 and 1998

termed as socially significant VI.6 In this article, we have was reported from an analysis of the Oxford Region Register of

adopted wherever possible the WHO terminology referring to Early Childhood Impairments.10 By contrast, a doubling of the

VI and severe visual impairment/blindness (SVI/BL). number of children ‘registered’ as blind in England and Wales

between 1982 and 2011, with the incidence increasing from

0.17/10 000 to 0.41/10 000 during that period, has recently

BURDEN OF VISUAL IMPAIRMENT been reported.11 While changes in certification practices may

An estimated 19 million of the world’s children are visually partly account for the latter, on balance it is likely that the

impaired, while 1.4 million are blind, according to WHO cri- overall trend in the UK is indeed of increasing frequency

teria.6 There are limited population-based data on the epidemi- through a combination of an increase in the population at risk,

ology of childhood VI and BL owing to the methodological and an increasing incidence of disorders which cause VI and

challenges to obtaining accurate information on uncommon and improved survival of children with VI.

heterogeneous disorders. In particular, robust data on the fre-

quency of mild/moderate VI are lacking for many countries CAUSES OF CHILDHOOD VISUAL IMPAIRMENT

where data are available for those with severe sight or visual The pattern of underlying disorders (‘causes’) of VI and BL vary

impairment/blindness (SVI/BL). considerably between and within (rural/urban settings) coun-

In some higher income countries, it is possible to estimate the tries, reflecting the regional balance of the determinants of spe-

prevalence of VI or SVI/BL using live registers of VI (eg, in the cific diseases, and the available resources to execute preventive

UK all children certified as sight impaired/severely sight strategies. Globally, the most frequent causes of childhood

impaired are then registered as such by the Social Services VI/SVI/BL are retinal disorders, glaucoma, corneal scarring ( pri-

system), although these may be incomplete or biased if registra- marily due to Vitamin A deficiency), cataract and cerebral

tion is voluntary (non-statutory). Data from middle and lower causes.7

income countries have tended to be derived from studies of

schools for blind children, but more recently there have been

Causes of visual impairment in higher income countries

large-scale population-based studies.7 These studies estimate the

Due to the challenges discussed earlier, the epidemiology of the

prevalence of childhood BL in middle and lower income coun-

individual causative disorders underlying childhood VI is uncer-

tries at between 0.2 and 7.8 per 10 000.7 The variation in

tain. The most common cause of childhood SVI/BL in industria-

prevalence of SVI/BL closely correlates with the under 5 years

lised countries such as the UK and USA is neurological or

childhood mortality rate in the region,8 with BL itself and the

cerebral disorder affecting the visual system, due to ischaemic,

causes of BL being linked to the increased risk of mortality.

developmental or unknown insults.12 13 While the USA data are

Using the UK as a model for industrialised countries, from a

based on studies of children registered in schools for the blind,

population-based incidence study, the annual cumulative inci-

the UK estimates are drawn from the British Childhood Visual

dence (in 2000) of SVI/BL is estimated to be 6/10 000 by age

Impairment Study (BCVIS), the only national population-based

15 years, with the incidence being highest (4/10 000) in the first

incidence study of childhood SVI/BL. Of the 493 children

newly diagnosed with SVI/BL in 2000, almost 50% of children

had cortical VI (figure 1).12 Optic nerve pathology accounted

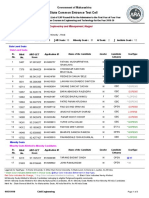

Table 1 Categorising vision: logMAR and Snellen measurement for 28% of childhood SVI/BL, and retinal disorders (including

scales, the WHO and UK categories of visual impairment (VI)

Acuity measurement Vision categories (using best achievable acuity

scales with both eyes open)

UK criteria for visual

impairment certification

LogMAR Snellen WHO definition

(linear (geometric of visual Full field of Very reduced

scale) scale) impairment vision field of vision

–0.1 6/4.8

0.0 6/6

0.1 6/7.5 No sight

No sight impairment

0.2 6/9

impairment

0.3 6/12

No sight

0.4 6/15

impairment*

0.5 6/18

0.6 6/24 Sight impairment

0.7 6/30 (previously termed

Moderate visual partially sighted)

0.8 6/36

impairment

0.9 6/48

1.0 6/60

1.1 5/60 Sight

Severe visual impairment

1.2 4/60 Severe sight

impairment

1.3 3/60 impairment

1.4 2/60 Blindness Severe sight Figure 1 The different causes of childhood severe visual impairment/

impairment blindness (SVI/BL) in the UK British Childhood Visual Impairment Study

(BCVIS) by anatomical site affected ( JR).

376 Solebo AL, et al. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:375–379. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002

Review

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 on 22 October 2013. Downloaded from http://adc.bmj.com/ on March 12, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.

retinopathy of prematurity) 29%. These three causes (insult to As hereditary causes account for a third of childhood SVI/BL

the cortex, optic nerve and retina) are also the most common in the BCVIS cohort, genetic counselling is potentially a tool in

causes of childhood SVI/BL in other higher income countries.13 the prevention of childhood VI due to known Mendelian eye

The majority of children in BCVIS (77%) had an additional conditions.

associated non-ophthalmic disorder, as has commonly been Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a globally important

described in similar populations.13 An increased risk of SVI/BL cause of childhood SVI/BL. Screening for ROP aims to detect

in children from ethnic minority groups, socio-economically infants with early stage disease to enable timely treatment to

deprived families, and those of low birth weight (<2500 g) was prevent the development of advanced disease leading to retinal

clearly identified, as was a 10% mortality risk in the first year detachment and BL. In higher income countries, routine screen-

after diagnosis; these findings being echoed by subsequent ing is undertaken of infants born earlier than 32 weeks’ gesta-

studies in industrialised countries.14 15 Preterm birth, inevitably tional age or with birth weight of less than 1500 g, according to

associated with low birth weight, has increased significantly over national guidance (http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/core/core_picker/

the last two decades in the UK16 and the neurological sequelae download.asp?id=180). In low and middle income countries,

of low birth weight are well recognised, with these children screening criteria and national programmes differ as infants of

being more likely to have white matter damage affecting the greater gestational age and/or birth weight are also considered

visual system or developmental anomalies of the optic nerve.17 to be at risk of developing ROP.24

There is also an increasing recognition of the impact of late

preterm birth (between 34 and 36 weeks’ gestation) on adverse Secondary prevention: early detection of visual impairment

neurodevelopmental outcomes.18 19 The continued increase in Prompt identification of childhood VI is essential as it allows

the number of preterm births can be expected to have an impact early intervention of ophthalmic and developmental interven-

on the frequency of VI globally, as can the increased survival of tions which are necessary to maximise visual outcomes. Early

children with neurological or neurodevelopmental disorders. ophthalmic intervention will be directed at the disorder itself

and the associated amblyopia. Early detection will also be

important to the success of emerging novel therapies, such as

MANAGEMENT OF CHILDHOOD VISUAL IMPAIRMENT

genetic therapies for inherited retinal dystrophies.25

It is beyond the scope of this review to discuss the ophthalmic

Paediatricians and other paediatric health professionals have a

management of individual disorders that cause VI. It is accepted

key role in the early detection of children with impaired vision

that children affected by these disorders require multidisciplin-

and/or visually impairing ophthalmic disorders. While parents

ary specialist teams with appropriate training and facilities and

and caregivers are often the first to suspect some degree of

ancillary structures, in keeping with the Royal College of

impaired vision in their child, in the UK almost half of all chil-

Ophthalmologist Quality Standards and Quality Indicators for

dren with SVI/BL first present to hospital-based paediatricians.9

Ophthalmic Care and Services for Children and Young People

This is particularly the case for the large population of children

(http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/page.asp?section=444§ionTitle=

who have additional associated systemic disorders.

Quality+Standards for Paediatric Ophthalmology) and its stand-

In approximately a fifth of children with SVI, reduced vision

ing report ‘Ophthalmic Services for Children’ (http://www.

is discovered in the context of the routine NHS Newborn and

rcophth.ac.uk/page.asp?section=293sectionTitle=Ophthalmic+

Infant Physical Examination Programme (NIPE).9 Childhood

Services+Guidance). Here we discuss the management of ‘all

screening programmes to detect disorders which cause VI exist

cause’ VI in terms of primary, secondary and tertiary

in varying forms in most industrialised countries. In the UK, the

prevention.

National Screening Committee (NSC) agrees standards for and

appraises the programmes for childhood vision screening, which

Primary prevention: preventing the insult currently comprises the examination of the eyes of all children

to the visual system in the first days following birth, and a second examination

In the BCVIS, the majority of children with SVI were blind due between the ages of 6 and 8 weeks as part of NIPE. Within the

to disorders or pathologies attributable to one or more prenatal Healthy Child Programme ( previously the Child Health

insults to the developing visual system. For many of these chil- Promotion Programme), screening by testing of acuity is under-

dren, the pathophysiology of the insult was associated with the taken at school entry age, of 4–5 years, to detect children with

developmental consequences of preterm birth. Preterm birth impaired vision—predominantly aimed at those with unilateral

(and low birth weight) is, globally, the most significant cause of amblyopia (eg, secondary to refractive error and/or strabismus)

newborn mortality and is rising in prevalence across many coun- as children with significantly reduced vision in both eyes are

tries.20 Prematurity is associated with multiple interrelated risk generally symptomatic and thus present earlier.

factors including maternal age, health and socio-economic Clinical surveillance of groups at increased risk of VI is also

status.21 22 Thus, it is a considerable challenge to direct prevent- an important strategy. In the UK, it is advocated that high risk

ive strategies towards this population. An active area of research groups such as children with neurological or neurodevelopmen-

that may impact on cerebral VI in addition to other adverse tal disorders, or with systemic disorders with known ophthalmic

neurological outcomes is therapeutic hypothermia, with a recent associations, or with a family history of ocular disorders, or

Cochrane systematic review supporting its efficacy in hypoxic those with sensori-neural hearing loss should undergo targeted

ischaemic encephalopathy in late preterm and term infants.23 ophthalmic assessments.26

A comparison of the relative importance of causes of child-

hood VI in higher, middle and lower income countries provides Tertiary prevention: managing the child with established

some indirect evidence of the beneficial impact of general public visual loss

heath preventive strategies such immunisation against measles All children with established visual loss require specialist train-

and rubella, and childhood nutritional programmes targeted ing and support for development, education and independent

against vitamin A deficiency in reducing the burden of BL due mobility in order to minimise the adverse impact of impaired

to corneal opacity, cataract and other ocular anomalies.7 8 13 sight. Thus, tertiary prevention of further burden from VI

Solebo AL, et al. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:375–379. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 377

Review

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 on 22 October 2013. Downloaded from http://adc.bmj.com/ on March 12, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.

involves continued ophthalmic input to limit the risk of further multidisciplinary management to minimise the impact of VI in

visual loss and provision of general care, support and training to childhood.

minimise the potential impact of impaired vision. A key prin-

ciple is that children with VI should be assessed and managed Contributors Both authors contributed to conception, design, data analysis and

by a multidisciplinary team, which can be virtual rather than interpretation, and article drafting, revision and final approval.

co-located, to ensure comprehensive and integrated interven- Funding The Centre for Paediatric Epidemiology and Biostatistics at ICH benefits

from funding support from the Medical Research Council in its capacity as the MRC

tion. The benefits to parents/families of a ‘key worker’ type

Centre of Epidemiology for Child Health. This work was undertaken at UCL Institute

service in which a dedicated professional provides information, of Child Health/Great Ormond Street Hospital for children which received a

support and liaison from the time around diagnosis are also well proportion of funding from the Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research

established.27 Centres funding scheme. JR is supported in part by the National Institute for Health

Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS

Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. JR and ALS are members of

Early developmental support the Ulverscroft Vision Research Group. The views expressed are those of the

The importance of early, vision-specific developmental support author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of

for all children with VI is well established. In the UK, Health. The funding organisations had no role in the design or conduct of this

approaches include the use of the Department of Education research.

Early Support Developmental Journal for babies and children Competing interests None.

with VI, which enables parents and carers to track their child’s Provenance and peer review Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

visual development in order to create an individualised frame-

work identifying current and potential future needs.28

REFERENCES

1 Salomao SR, Ventura DF. Large sample population age norms for visual acuities

Certification and registration of childhood visual impairment

obtained with Vistech-Teller Acuity Cards. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci

Certification of a child’s VI (by the ophthalmologist) enables 1995;36:657–70.

registration of the child as sight impaired by Social Services or 2 Mayer DL, Beiser AS, Warner AF, et al. Monocular acuity norms for the Teller Acuity

an equivalent governmental body, allowing the family improved Cards between ages one month and four years. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci

access to educational and welfare support. Certification remains 1995;36:671–85.

3 Wiesel T, Hubel DH. Single-cell responses in striate cortex of kittens deprived of

non-statutory in the UK, and although there is evidence that vision in one eye. J Neurophysiol 1963;26:1003–17.

most eligible children are offered certification in a timely 4 Hooks BM, Chen C. Critical periods in the visual system: changing views for a

manner, variations in practice exist.29 In some specialised ter- model of experience-dependent plasticity. Neuron 2007;56:312–26.

tiary ophthalmic units, certification of VI is facilitated by a ‘key 5 Birch EE, Stager DR. The critical period for surgical treatment of dense congenital

unilateral cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1996;37:1532–8.

worker’ for example, an Eye Clinic Liaison Officer, who is also

6 World Health Organisation. Visual impairment and blindness. 2012. http://www.

the point of contact for families, providing information and who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs282/en/. (accessed August 2013).

assistance. 7 Courtright P, Hutchinson AK, Lewallen S. Visual impairment in children in middle-

and lower-income countries. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:1129–34.

Educational support 8 Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020—the right

to sight. Bull World Health Organ 2001;79:227–32.

Certification is not a prerequisite for referral to childhood VI 9 Rahi JS, Cumberland PM, Peckham CS. Improving detection of blindness in

services or vision-related educational needs assessment in the childhood: the British Childhood Vision Impairment study. Pediatrics 2010;126:

UK. Early referral/notification of children with VI/SVI/BL and e895–903.

early involvement of a Peripatetic Visual Impairment Service/ 10 Bodeau-Livinec F, Surman G, Kaminski M, et al. Recent trends in visual impairment

and blindness in the UK. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:1099–104.

Peripatetic Teachers of Children with VI is recognised to be of

11 Mitry D, Bunce C, Wormald R, et al. Childhood visual impairment in England: a

value. A formal low vision aids assessment can be provided by rising trend. Arch Dis Child 2012;98:378–80.

ophthalmic services or by educationalists and covers aids such as 12 Rahi JS, Cable N. Severe visual impairment and blindness in children in the UK.

hand-held or self-supporting magnifiers. More advanced adap- Lancet 2003;362:1359–65.

tive technologies include video magnifiers, closed circuit televi- 13 Kong L, Fry M, Al-Samarraie M, et al. An update on progress and the changing

epidemiology of causes of childhood blindness worldwide. J AAPOS 2012;16:

sion relays of printed material or electronic relay or material on 501–7.

laptop-based/tablet-based large font displays and voice activated/ 14 Pai AS, Wang JJ, Samarawickrama C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for visual

voice recognition and text to speech software. Simple strategies impairment in preschool children the sydney paediatric eye disease study.

such as sitting a child nearer the whiteboard in the classroom Ophthalmology 2011;118:1495–500.

15 Cumberland PM, Pathai S, Rahi JS. Prevalence of eye disease in early childhood and

can also be valuable. In the UK, currently half of school-aged

associated factors: findings from the millennium cohort study. Ophthalmology

visually impaired children receive education in mainstream 2010;117:2184–90.

schools with or without specialist visual resources, while, due to 16 Costeloe KL, Hennessy EM, Haider S, et al. Short term outcomes after extreme

the significant population of children with multisystem disease, preterm birth in England: comparison of two birth cohorts in 1995 and 2006 (the

a third of children with SVI/BL attend schools for children with EPICure studies). BMJ 2012;345:e7976..

17 Hellgren K, Hellstrom A, Martin L. Visual fields and optic disc morphology in very

physical disabilities or learning difficulties.30 low birthweight adolescents examined with magnetic resonance imaging of the

brain. Acta Ophthalmol 2009;87:843–8.

SUMMARY 18 Kerstjens JM, de Winter AF, Bocca-Tjeertes IF, et al. Developmental delay in

The population of visually impaired children in high, middle moderately preterm-born children at school entry. J Pediatr 2011;159:92–8.

19 Engle WA, Tomashek KM, Wallman C. “Late-preterm” infants: a population at risk.

and lower income countries differ considerably between and

Pediatrics 2007;120:1390–401.

within countries. The numerous and mainly uncommon disor- 20 March of Dimes, PMNCH, Save the Children, WHO. Born Too Soon: The Global

ders which can cause impaired vision results in heterogeneous Action Report on Preterm Birth. Eds CP Howson, MV Kinney, JE Lawn. World

population which includes a substantial proportion (for SVI/BL, Health Organization. Geneva, 2012. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2012/

the majority) of children with additional systemic disorders or 201204_borntoosoon-report.pdf. (Accessed August 2013).

21 Dekker GA, Lee SY, North RA, et al. Risk factors for preterm birth in an

impairments whose needs differ substantially from those with international prospective cohort of nulliparous women. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e39154.

isolated vision impairment. Paediatricians and other paediatric 22 Meis PJ, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, et al. The preterm prediction study: risk factors

professionals have a key role in early detection and for indicated preterm births. Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the National

378 Solebo AL, et al. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:375–379. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002

Review

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 on 22 October 2013. Downloaded from http://adc.bmj.com/ on March 12, 2024 by guest. Protected by copyright.

Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Am J Obstet Gynecol 27 Rahi JS, Manaras I, Tuomainen H, et al. Meeting the needs of parents around the

1998;178:562–7. time of diagnosis of disability among their children: evaluation of a novel program

23 Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, et al. Cooling for newborns with hypoxic ischaemic for information, support, and liaison by key workers. Pediatrics 2004;114:

encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(1):CD003311. e477–82.

24 Gilbert C, Fielder A, Gordillo L, et al. Characteristics of infants with severe 28 Dale N, Salt A. Early support developmental journal for children with visual

retinopathy of prematurity in countries with low, moderate, and high levels of impairment: the case for a new developmental framework for early intervention.

development: implications for screening programs. Pediatrics 2005;115: Child Care Health Dev 2007;33:684–90.

e518–25. 29 Cumberland PM, Peckham CS, Rahi JS. Blindness certification of children 1 year

25 Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function after diagnosis: findings from the British Childhood Vision Impairment Study. Br J

in Leber’s congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2231–9. Ophthalmol 2010;94:1694–5.

26 Hall DMB, Elliman D. Screening for vision defects. In: Hall DMB, Elliman D, eds. 30 Keil S. Survey of educational provision for blind and partially sighted children in

Health for all children. Oxford University Press 2006:226–37. England, Scotland and Wales in 2002. Br J Vis Impairment 2003;46:93–7.

Solebo AL, et al. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:375–379. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-303002 379

You might also like

- Cockney MonologuesDocument2 pagesCockney MonologuesLaReceHawkins86% (7)

- Greenbook Research Industry Trends Report 2020Document126 pagesGreenbook Research Industry Trends Report 2020Paul KendallNo ratings yet

- THINK L4 Unit 6 Grammar BasicDocument2 pagesTHINK L4 Unit 6 Grammar Basicniyazi polatNo ratings yet

- Sir Imran SynopsisDocument13 pagesSir Imran Synopsismethoo143No ratings yet

- POOR-EYESIGHT BDocument17 pagesPOOR-EYESIGHT Bkenneth mayaoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Criminology (Review Materials For 2013 Criminology Board Examination)Document43 pagesIntroduction To Criminology (Review Materials For 2013 Criminology Board Examination)Clarito Lopez88% (33)

- Childhood BlindnessDocument6 pagesChildhood BlindnessMonika Diaz KristyanindaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Tuna NetraDocument12 pages2021 Tuna NetraAnnessa N PradetaNo ratings yet

- Childhood Amblyopia: Current Management and New Trends: Invited ReviewDocument12 pagesChildhood Amblyopia: Current Management and New Trends: Invited ReviewVrishab KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Current Management of Childhood Amblyopia: Shin Hae ParkDocument12 pagesCurrent Management of Childhood Amblyopia: Shin Hae ParkSyarifah Thalita NabillaNo ratings yet

- 21-29 Clinical+Characteristics+of+Children+With+Refractive+Amblyopia+at+Cipto+Mangunkusumo+National+Referral+Hospital Rev1Document9 pages21-29 Clinical+Characteristics+of+Children+With+Refractive+Amblyopia+at+Cipto+Mangunkusumo+National+Referral+Hospital Rev1firmianisaNo ratings yet

- 2 - Residual Vision & Integration - BJVIDocument3 pages2 - Residual Vision & Integration - BJVISanjiv DesaiNo ratings yet

- Vision Screening For Infants and Children - 2022Document6 pagesVision Screening For Infants and Children - 2022Fabricia LatterellNo ratings yet

- Artigo 4 Chadha2010Document5 pagesArtigo 4 Chadha2010Tiago BaraNo ratings yet

- Approach To StrabismusDocument11 pagesApproach To StrabismusMuvenn KannanNo ratings yet

- 03 Quality of Life in BlindDocument12 pages03 Quality of Life in BlindIvana tomićNo ratings yet

- Cause of Amblyopia in Adult Patients A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument5 pagesCause of Amblyopia in Adult Patients A Cross-Sectional StudyRagni Mishra100% (2)

- Ocular Disorders in The NewbornDocument11 pagesOcular Disorders in The NewbornXimena ParedesNo ratings yet

- A Study to Assess the Prevalence of Impaired Visual Acuity Among Primary School Children of Selected Rural Areas of Vijayapur District With a View to Provide an Informational Booklet on Management Regarding Impaired VisDocument5 pagesA Study to Assess the Prevalence of Impaired Visual Acuity Among Primary School Children of Selected Rural Areas of Vijayapur District With a View to Provide an Informational Booklet on Management Regarding Impaired VisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Paediatric Cataracts Clinical and Experimental Advances in Congenital andDocument17 pagesPaediatric Cataracts Clinical and Experimental Advances in Congenital andCahyo GuntoroNo ratings yet

- World Sight Day - 13 October 2022Document2 pagesWorld Sight Day - 13 October 2022Times MediaNo ratings yet

- Eye - Lond - 2024 Apr 10.Document6 pagesEye - Lond - 2024 Apr 10.HemerobibliotecaHospitalNo ratings yet

- Psychological Implication of Visual ImpairmentDocument6 pagesPsychological Implication of Visual ImpairmentSakthikumarNo ratings yet

- Myopia PDFDocument12 pagesMyopia PDFHusam SuleimanNo ratings yet

- 3739-Article Text-45139-2-10-20220815Document10 pages3739-Article Text-45139-2-10-20220815Aine ChloeNo ratings yet

- Eye Disease Nigeria ChildrenDocument8 pagesEye Disease Nigeria ChildrenYodhaBoyAdhikakusumaNo ratings yet

- Study of Vision Screening in School Children Between 5 and 15 YearsDocument16 pagesStudy of Vision Screening in School Children Between 5 and 15 YearsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Epidemiology, Genetics and Treatments For MyopiaDocument14 pagesEpidemiology, Genetics and Treatments For MyopiaAlbert YeeNo ratings yet

- Visual Impairment and Low Vision A Systematic StudyDocument11 pagesVisual Impairment and Low Vision A Systematic StudyWeb ResearchNo ratings yet

- Myopia - EyeWikiDocument1 pageMyopia - EyeWikiRima MaulinaNo ratings yet

- Macppt On Blindness by ArmaanDocument9 pagesMacppt On Blindness by ArmaanArmaandeep DhillonNo ratings yet

- A Study of Ocular Abnormalities in Children With Cerebral PalsyDocument6 pagesA Study of Ocular Abnormalities in Children With Cerebral PalsySuvratNo ratings yet

- Biology Investigatory Project On Eye DiseasesDocument18 pagesBiology Investigatory Project On Eye DiseasesBHALAJI KARUNANITHI100% (1)

- Development of Visual Acuity and Contrast Sensitivity in ChildrenDocument8 pagesDevelopment of Visual Acuity and Contrast Sensitivity in ChildrenmatsalNo ratings yet

- Visual ImpairmentDocument9 pagesVisual ImpairmentMeti Guda100% (1)

- Epidemiology, Genetics and Treatments For MyopiaDocument17 pagesEpidemiology, Genetics and Treatments For MyopiaRyasNo ratings yet

- Pediatr Clin Na 2014 Jun 61 (3) 495Document9 pagesPediatr Clin Na 2014 Jun 61 (3) 495mickymed_No ratings yet

- Student Handbook Orthoptics.Document13 pagesStudent Handbook Orthoptics.Nur AminNo ratings yet

- M. Arslan 1Document7 pagesM. Arslan 1arslangreat2002No ratings yet

- Jurnal MataDocument8 pagesJurnal MatamarinarizkiNo ratings yet

- Visual ImpairmentsDocument48 pagesVisual Impairmentsoroniallan02No ratings yet

- Statement On Cortical Visual ImpairmentDocument14 pagesStatement On Cortical Visual ImpairmentAmal AlmutiriNo ratings yet

- Understanding Low Functioning Cerebral Visual ImpairmentDocument8 pagesUnderstanding Low Functioning Cerebral Visual ImpairmentShobithaNo ratings yet

- Eye ExaminationDocument9 pagesEye ExaminationFilbert KunardiNo ratings yet

- Implications of Visual ImpairmentDocument11 pagesImplications of Visual ImpairmentRakesh JanguNo ratings yet

- Bio Khushil 12Document23 pagesBio Khushil 12khushilgajpal2007No ratings yet

- BIOLOGY INVESTIGATORY - Docx2.oDocument27 pagesBIOLOGY INVESTIGATORY - Docx2.oK GhatageNo ratings yet

- Blind ReportDocument72 pagesBlind Reportmindworkz proNo ratings yet

- Congenital Preventable Blindness: of ChildDocument4 pagesCongenital Preventable Blindness: of ChildJustin Michal DassNo ratings yet

- Visual Impairments: Reporters: Arcenal, Sandra Cauilan, Cyril B. Taguiam, Sir Joseph CDocument30 pagesVisual Impairments: Reporters: Arcenal, Sandra Cauilan, Cyril B. Taguiam, Sir Joseph CCyril CauilanNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Refractive Error and Visual ImpairmeDocument9 pagesPrevalence of Refractive Error and Visual ImpairmeGeraldin GarayNo ratings yet

- Sumi - Presentation On BlindnessDocument23 pagesSumi - Presentation On Blindnessabhigyan priyadarshanNo ratings yet

- Tatalaksana Low Vision Pada Pasien Moderate Visual Impairment Dengan Ambliopia Deprivatif - Annisa RahayuDocument11 pagesTatalaksana Low Vision Pada Pasien Moderate Visual Impairment Dengan Ambliopia Deprivatif - Annisa RahayuMarini Yusufina LubisNo ratings yet

- 89 110 OngtangcoDocument22 pages89 110 OngtangcoEdward AysonNo ratings yet

- Cortical Visual Impairment: Pediatrics in Review November 2009Document13 pagesCortical Visual Impairment: Pediatrics in Review November 2009Amal AlmutiriNo ratings yet

- Background: FrequencyDocument10 pagesBackground: FrequencyJenylia HapsariNo ratings yet

- 2 Cerebral Visual Impairment-Related Vision ProblemsDocument7 pages2 Cerebral Visual Impairment-Related Vision ProblemsMonica Laura SanchezNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ambliopia 2Document25 pagesJurnal Ambliopia 2MusdalipaNo ratings yet

- VisionDocument8 pagesVisionapi-367611011No ratings yet

- Visual Impairment and Learning Disabilities: University of Thessaly Department of Special EducationDocument12 pagesVisual Impairment and Learning Disabilities: University of Thessaly Department of Special EducationNurul Husna D'uyunkNo ratings yet

- Associations of Anisometropia With Unilateral Amblyopia, Interocular Acuity Difference, and Stereoacuity in PreschoolersDocument9 pagesAssociations of Anisometropia With Unilateral Amblyopia, Interocular Acuity Difference, and Stereoacuity in PreschoolersCalvin NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cataract-Approach and Management ReviewDocument6 pagesCongenital Cataract-Approach and Management ReviewFirgietaPotterNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence of Myopia Among School-Going ChildrDocument6 pagesThe Prevalence of Myopia Among School-Going ChildrsalmanNo ratings yet

- Hemispheric Structure and FuctionDocument4 pagesHemispheric Structure and FuctionDebby RizkyNo ratings yet

- Final NHD Annotated BibliographyDocument7 pagesFinal NHD Annotated Bibliographyapi-616585007No ratings yet

- Vikram-Betal Case StudyDocument5 pagesVikram-Betal Case StudyRavi SawantNo ratings yet

- B1.1-Self-Study Đã Sài XongDocument5 pagesB1.1-Self-Study Đã Sài XongVy CẩmNo ratings yet

- Java Cheat Sheet & Quick ReferenceDocument16 pagesJava Cheat Sheet & Quick Referencedad dunnoNo ratings yet

- Colonialism and Imperialism by Usman KhanDocument2 pagesColonialism and Imperialism by Usman KhanUSMANNo ratings yet

- Reading PashtoDocument17 pagesReading PashtoUmer Khan0% (1)

- Adetunji CVDocument5 pagesAdetunji CVAdetunji AdegbiteNo ratings yet

- (G.R. No. 136448. November 3, 1999.) Lim Tong Lim, Petitioner, V. Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, Inc, Respondent. DecisionDocument23 pages(G.R. No. 136448. November 3, 1999.) Lim Tong Lim, Petitioner, V. Philippine Fishing Gear Industries, Inc, Respondent. Decisionalay orejudosNo ratings yet

- Leadership in Virtual TeamsDocument13 pagesLeadership in Virtual TeamsBrandon ManuelNo ratings yet

- I Love Algorithms - Machine Learning CardsDocument6 pagesI Love Algorithms - Machine Learning CardsCarlos Manuel Ventura MatosNo ratings yet

- Max WeberDocument11 pagesMax WeberPKBM AL MUTHINo ratings yet

- Crim Pro 2004-2010 Bar QuestionsDocument4 pagesCrim Pro 2004-2010 Bar QuestionsDennie Vieve IdeaNo ratings yet

- 7 Eleven MalaysiaDocument10 pages7 Eleven MalaysiaKimchhorng HokNo ratings yet

- Waterfront Regeneration As A Sustainable Approach To City Development in MalaysiaDocument10 pagesWaterfront Regeneration As A Sustainable Approach To City Development in MalaysiaРадоњић МајаNo ratings yet

- Indonesian - 1 - 1 - Audiobook - KopyaDocument93 pagesIndonesian - 1 - 1 - Audiobook - KopyaBurcu BurcuNo ratings yet

- Distress Tolerance Handout 5 - Pros and Cons PDFDocument1 pageDistress Tolerance Handout 5 - Pros and Cons PDFRobinNo ratings yet

- Of Mice and Men EssayDocument7 pagesOf Mice and Men Essayjon782No ratings yet

- 85th BSC AgendaDocument61 pages85th BSC AgendaSiddharth MohantyNo ratings yet

- Passive VoiceDocument2 pagesPassive VoiceJoseph HopperNo ratings yet

- Mass Transfer in Fermentation ProcessDocument5 pagesMass Transfer in Fermentation ProcessSimone Bassan Zuicker ElizeuNo ratings yet

- Capr-Iii En4115 PDFDocument49 pagesCapr-Iii En4115 PDFYT GAMERSNo ratings yet

- Better Get 'It in Your SoulDocument4 pagesBetter Get 'It in Your SoulJeremiah AnnorNo ratings yet

- IBM InstanaDocument2 pagesIBM InstanaArjun Jaideep BhatnagarNo ratings yet

- Philips+22PFL3403-10+Chassis+TPS1 4E+LA+LCD PDFDocument53 pagesPhilips+22PFL3403-10+Chassis+TPS1 4E+LA+LCD PDFparutzu0% (1)