Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Final Solut-WPS Office

The Final Solut-WPS Office

Uploaded by

arpitab369Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Final Solut-WPS Office

The Final Solut-WPS Office

Uploaded by

arpitab369Copyright:

Available Formats

‘The Final Solution’ as a Partition Literature.

The female refugee subject in the subversive arena of Partition and attempts to understand the vulnerabilities of the

female subject in the politico-patriarchal world of Partition, through a close reading of Manik Bandopadhyay’s short

story, “The Final Solution”. Located within a suspended juridico-legal order, the considerations of the ethical are often

nuanced for the refugee. The present chapter explores how the refugee feminine and her agency is threatened by the

violating milieu of a pervert patriarchy and how in turn the feminine responds with an equally reciprocated rhetoric of

counter-violence. The chapter further contemplates if the counter-violence can lay its claim to emancipation or if it

remains a mere reaction formation to the violently oppressive and hegemonic patriarchal milieu of Partition.

The Partition has been one of the most traumatic events in the history of the Indian sub-continent, leaving deep

psychological scars that continue to haunt us within and without. As Ashis Nandy and many others have commented,

silence became the main psychological defence of the survivors, which is why researchers have had to wait long and

dig deep for partition narratives. Along with the oblivion of silence, women, especially mothers – as double-victims of

both patriarchal power structures and the violence and violations of the Partition – have had to face erasure from the

Partition discourse as well.

“The Final Solution” is a story by Manik Bandopadhyay, who is an Indian Bengali, writing about the destruction of

values and the politics of power and sexuality in the spiralling refugee problem in Calcutta, which was a direct

aftermath of the 1947 Partition. Many of the Hindu families who left their homes in East Pakistan and came to West

Bengal in India, could not find refuge in the overcrowded camps. They were forced to settle in any place they could

find, including public places like the Sealdah Railway Station.

The protagonist of the story, Mallika, resides on this railway platform: “Mallika’s family had a place, the length of a

spread out mattress. Everything, everyone is squeezed in there – Mallika, her husband Bhushan, their two-and-half-

year-old son Khokon and her widowed sister-in-law Asha; tin suitcases, beddings, bundles, pots and pans”. The very

precariousness and transit-oriness of such a location foregrounds the family’s rootless and destabilised existence,

and the irony of having a “mattress kingdom” is sharper in the context of the irreversible displacement suffered by

them.

When the tout, Pramatha, comes to Mallika with the offer of “some jobs still available for women”, she understands

the risk, yet one look at her child, “now reduced to a skeleton”, makes her agree because, as she says, “There’s no

other way out for us”. It is the compulsions of maternal love that prompt her to compromise her body and self-

respect. As she says to her sister-in-law, Asha, “I would be ready to die if that could keep my child alive”.

The act of murdering Pramatha empowers her, and she says, “What did he take me for? Am I weak just because I’m a

woman?” She decides henceforth to carry a knife when engaging with men, because violence has become the

currency of human negotiation during Partition. From a victim, she becomes an agent of her own and her family’s

destiny. Any moral guilt that she might have felt is erased by the fierce mother-love that propels her. The text is open-

ended; the writer does not judge her morally or punish her legally, and even the reader is compelled to withhold

judgement in the context of the sheer desperation of the plight of the refugee mother.

You might also like

- Sample Affidavit of Solo ParentDocument1 pageSample Affidavit of Solo Parentxylee apilado72% (18)

- The Final Solution SummaryDocument7 pagesThe Final Solution SummarySukannaya Daptari100% (3)

- An American ExodusDocument24 pagesAn American ExodusDaria PiccottiNo ratings yet

- Dse - Partition Literature B.A. (Hons.) English VI SemesterDocument11 pagesDse - Partition Literature B.A. (Hons.) English VI SemesterSajal DasNo ratings yet

- Attia Hosain S Sunlight On A Broken ColumnDocument9 pagesAttia Hosain S Sunlight On A Broken ColumnDeandra D'Cunha100% (1)

- Final SolutionDocument9 pagesFinal Solutionchumpilaskar07No ratings yet

- Partition Literature IDocument14 pagesPartition Literature ISania MustafaNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH PAPER Manto FinalDocument8 pagesRESEARCH PAPER Manto FinalUroosa KhanNo ratings yet

- 11478Document2 pages11478arpitab369No ratings yet

- The Final Solution PharagraphDocument1 pageThe Final Solution PharagraphRashmi Mehra100% (1)

- Cracking IndiaDocument17 pagesCracking IndiasaminaNo ratings yet

- A Leaf in The StormDocument13 pagesA Leaf in The Stormsubhadip pal100% (1)

- Female Body As Hieroglyphics of Partition Violence: Reading Lalithambika Antharjanam'S "A Leaf in The Storm"Document13 pagesFemale Body As Hieroglyphics of Partition Violence: Reading Lalithambika Antharjanam'S "A Leaf in The Storm"Sajal DasNo ratings yet

- Incarcerating Women in Tribal Areas: A Third World Feminist CritiqueDocument10 pagesIncarcerating Women in Tribal Areas: A Third World Feminist CritiqueProf. Liaqat Ali MohsinNo ratings yet

- Ice Candy Man PresentationDocument22 pagesIce Candy Man PresentationNMK@KC82% (34)

- Feminism in The Fiction of Bapsi SidhwaDocument11 pagesFeminism in The Fiction of Bapsi SidhwaYasir AslamNo ratings yet

- IsmatDocument4 pagesIsmathh rickyNo ratings yet

- The Breast Giver As A FemaleDocument8 pagesThe Breast Giver As A FemaleNAZIR ASHRAFNo ratings yet

- ALITsDocument4 pagesALITsZenith RoyNo ratings yet

- Apf and CultureDocument5 pagesApf and CultureShahzadNo ratings yet

- Humanities-Gender, Self Representation and Sexualized Spaces-Tanvi KhannaDocument6 pagesHumanities-Gender, Self Representation and Sexualized Spaces-Tanvi KhannaImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- A Margin'S March To The Mainstream - The Story of My Sanskrit'Document8 pagesA Margin'S March To The Mainstream - The Story of My Sanskrit'TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Anjali CctmidsemDocument7 pagesAnjali CctmidsemAnjalee DurgeshNo ratings yet

- Literatures of India Assignment - WidowDocument4 pagesLiteratures of India Assignment - WidowAlisa RahmanNo ratings yet

- LLDocument14 pagesLLFanstaNo ratings yet

- DalitDocument9 pagesDalitbaglovely72No ratings yet

- SANGEETADocument7 pagesSANGEETAsjn2tz5kryNo ratings yet

- Kanad Prajna Das - 120351103Document6 pagesKanad Prajna Das - 120351103Kanad Prajna DasNo ratings yet

- 22.sona Gaur ArticleDocument5 pages22.sona Gaur ArticleFaith In Jesus Christ.No ratings yet

- Analysis of Patriarchal Pressures and The Struggle of A Pakistan Woman in My Feudal LordDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Patriarchal Pressures and The Struggle of A Pakistan Woman in My Feudal LordAnanya ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- 1Document4 pages1meghanamarrapu6No ratings yet

- Vol 4. Issue 2 Apr Jun 2022 Rehman Maqbool Akhtar The Representation of Womens IdentityDocument10 pagesVol 4. Issue 2 Apr Jun 2022 Rehman Maqbool Akhtar The Representation of Womens Identityzia ur rehmanNo ratings yet

- Nadia Ramzan.Document8 pagesNadia Ramzan.Anns NasirNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument42 pagesTerm PaperEsha TiwariNo ratings yet

- 11.-Amal-SarkarDocument7 pages11.-Amal-Sarkarddbddb149No ratings yet

- Ice Candyman PresentationDocument36 pagesIce Candyman PresentationIris Delacroix0% (1)

- Partition Short Story Analysis English Hons. IIIrd Year DUDocument6 pagesPartition Short Story Analysis English Hons. IIIrd Year DUROUSHAN SINGH100% (2)

- Stoicism: Portrayal of Women in Khamosh Pani, Pinjar and Eho Hamara JeevnaDocument4 pagesStoicism: Portrayal of Women in Khamosh Pani, Pinjar and Eho Hamara JeevnaIJELS Research Journal100% (1)

- 1 Af 3Document43 pages1 Af 3DaffodilNo ratings yet

- Fullpaper CharithaLiyanageDocument17 pagesFullpaper CharithaLiyanageJunjiNo ratings yet

- Attia Hosain's Sunlight On A Broken ColumnDocument9 pagesAttia Hosain's Sunlight On A Broken ColumnDr.Rumpa Das80% (5)

- Bapsi Sidhwa's Ice-Candy-Man: A Feminist Perspective: Showkat Hussain DarDocument6 pagesBapsi Sidhwa's Ice-Candy-Man: A Feminist Perspective: Showkat Hussain DarNawaz bhatti345No ratings yet

- DR Saptarshi's AssignmentDocument6 pagesDR Saptarshi's AssignmentDivyansh BhattNo ratings yet

- Dr. Mallika Tripathi Paper FinalDocument12 pagesDr. Mallika Tripathi Paper FinalTRIDIP PANDITNo ratings yet

- Transnational Feminism in Sidhwa S CracDocument14 pagesTransnational Feminism in Sidhwa S CracNadeem NkNo ratings yet

- Cold MeatDocument6 pagesCold Meatddbddb149No ratings yet

- FACING FUNDAMENTALISM B. S. VarmaDocument11 pagesFACING FUNDAMENTALISM B. S. Varmabhagya ShreeNo ratings yet

- No Shame For The Sun Lives of ProfessionDocument3 pagesNo Shame For The Sun Lives of Professionarikakk88No ratings yet

- Women's Exploitation in The Feudal Society - A Case Study of My Feudal LordDocument8 pagesWomen's Exploitation in The Feudal Society - A Case Study of My Feudal Lordfahad.uddinNo ratings yet

- PaperDocument15 pagesPaperBarnali SahaNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Githa HariharanDocument4 pagesThesis On Githa Hariharanbethsalazaraurora100% (2)

- Ice PDFDocument6 pagesIce PDFKhushnood AliNo ratings yet

- Negation of Humanity An Analysis of MulkDocument3 pagesNegation of Humanity An Analysis of MulkkarthicshajiuppuveettilNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument32 pagesChapterShanza MunirNo ratings yet

- Dse A3Document6 pagesDse A3swapneragnivat4loveNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENTDocument9 pagesASSIGNMENTRobin SinghNo ratings yet

- Female Suppression and MArginalizationDocument7 pagesFemale Suppression and MArginalizationKiran AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Samskara 2Document6 pagesSamskara 2Janu DaimariNo ratings yet

- The Feminine and the Familial: A Foray into the Fictional World of Shashi DeshpandeFrom EverandThe Feminine and the Familial: A Foray into the Fictional World of Shashi DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- Untouchable Fictions: Literary Realism and the Crisis of CasteFrom EverandUntouchable Fictions: Literary Realism and the Crisis of CasteNo ratings yet

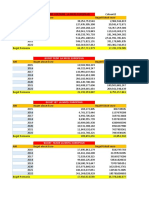

- Buget Fedr La Nivel EuropeanDocument4 pagesBuget Fedr La Nivel EuropeanFlorin HarabagiuNo ratings yet

- AGM Minutes 2008Document5 pagesAGM Minutes 2008api-19987050No ratings yet

- Jailhouse Lawyer by Margolin PhillipDocument9 pagesJailhouse Lawyer by Margolin PhillipGoodangs idNo ratings yet

- Kanye Changes Name To Yitler: Related NewsDocument1 pageKanye Changes Name To Yitler: Related NewsDorian BrouwerNo ratings yet

- Delegate Training GuideDocument39 pagesDelegate Training GuideShraddhaNo ratings yet

- WASH and Gender Technical Brief July 2020Document9 pagesWASH and Gender Technical Brief July 2020Paolo SordiniNo ratings yet

- XI 4.2 The Rising of The MoonDocument13 pagesXI 4.2 The Rising of The Moonyashvi100% (1)

- Chapter 3 Purpose of Studying Comparative EducationDocument6 pagesChapter 3 Purpose of Studying Comparative EducationDhes CastroNo ratings yet

- PE.2019-20.0074 - Thunga HospitalDocument4 pagesPE.2019-20.0074 - Thunga HospitalAnonymous vFrxVNNo ratings yet

- Tax Is A Compulsory Contribution To State RevenueDocument2 pagesTax Is A Compulsory Contribution To State Revenuefahad pansotaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Preliminary InjunctionDocument11 pagesMotion For Preliminary Injunctionrharris8832No ratings yet

- Jason Assignment Edit 1Document2 pagesJason Assignment Edit 1johnawhitney4801No ratings yet

- Tucker 1987Document5 pagesTucker 1987Mario RosanoNo ratings yet

- RA 10912 CPD LawDocument11 pagesRA 10912 CPD LawNonoyTaclino0% (1)

- Mini Magic 6Document67 pagesMini Magic 6Venkat krishna100% (1)

- Section 8 - Due Diligence: DD/08: Pest Control and ReportingDocument2 pagesSection 8 - Due Diligence: DD/08: Pest Control and Reportingmuhammed asharudheenNo ratings yet

- 10 PNB v. Andrada Electric and Engineering Co.Document3 pages10 PNB v. Andrada Electric and Engineering Co.Stephen Daniel JavierNo ratings yet

- Hovey Island LawsuitDocument26 pagesHovey Island Lawsuit7 NewsNo ratings yet

- J 2021 SCC OnLine Del 4146Document7 pagesJ 2021 SCC OnLine Del 4146NET NOBODYNo ratings yet

- Key To Abbreviations: Updated Licensed Qualified Water Contractors For The Year 2013Document19 pagesKey To Abbreviations: Updated Licensed Qualified Water Contractors For The Year 2013Anonymous VAyE02PNo ratings yet

- TL 3Document16 pagesTL 3Hriday ShahNo ratings yet

- PDS VargasDocument13 pagesPDS Vargasfe mosingNo ratings yet

- Cir vs. SantosDocument9 pagesCir vs. SantosLalaine FelixNo ratings yet

- AM Civil ContractFinal 14818Document7 pagesAM Civil ContractFinal 14818Kuldeep SharmaNo ratings yet

- Service Level Commitment (SLC) : JULY 02, 2021Document12 pagesService Level Commitment (SLC) : JULY 02, 2021Addis AbabaNo ratings yet

- H.L.A. Hart On Justice and Morality: John TasioulasDocument27 pagesH.L.A. Hart On Justice and Morality: John TasioulasMuhammad HafeezNo ratings yet

- Transport MCQ AnswerDocument3 pagesTransport MCQ AnswerManas RanjanNo ratings yet

- Negotiable InstrumentsDocument17 pagesNegotiable InstrumentsJeaner AckermanNo ratings yet