Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1 viewsPre-service and Novice Teachers’ Perceptions on Second Language Teacher Education Initial English Language Teacher Education

Pre-service and Novice Teachers’ Perceptions on Second Language Teacher Education Initial English Language Teacher Education

Uploaded by

a1dhillonPre service perceptions

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- A Teacher Guide To Classroom Research PDFDocument237 pagesA Teacher Guide To Classroom Research PDFNoor Dedhy83% (24)

- Task 1 - Teacher Development ReflectionDocument3 pagesTask 1 - Teacher Development ReflectionHarold Bonilla PerezNo ratings yet

- Teaching Vocabulary by Paul NationDocument9 pagesTeaching Vocabulary by Paul Nationanna_elpux20098387100% (1)

- Lola Seaton, The Ends of Criticism, NLR 119, September October 2019 PDFDocument28 pagesLola Seaton, The Ends of Criticism, NLR 119, September October 2019 PDFEnio VieiraNo ratings yet

- Preparing Pre Service Teachers For The SDocument18 pagesPreparing Pre Service Teachers For The SJulian DuqueNo ratings yet

- Empowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyDocument12 pagesEmpowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyAngely Chacón BNo ratings yet

- TESOL Quarterly - 2019 - Hennebry Leung - Transitioning From Master S Studies To The Classroom From Theory To PracticeDocument27 pagesTESOL Quarterly - 2019 - Hennebry Leung - Transitioning From Master S Studies To The Classroom From Theory To PracticeNourhanNo ratings yet

- SLA Final Assignment - Research Proposal (Hương - Đô - Liên - Lĩnh)Document38 pagesSLA Final Assignment - Research Proposal (Hương - Đô - Liên - Lĩnh)miniNo ratings yet

- Researching English Language and Literacy Development in SchoolsDocument22 pagesResearching English Language and Literacy Development in Schoolsapi-27788847No ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document22 pagesFULLTEXT01Mig Mony BrownNo ratings yet

- Austtaralian and VietnameseDocument22 pagesAusttaralian and VietnameseeltcanNo ratings yet

- VIERA Task in ClassroomDocument24 pagesVIERA Task in ClassroomjanNo ratings yet

- Tian2020 Promoting Translanguaging in TESOL teacher educationDocument23 pagesTian2020 Promoting Translanguaging in TESOL teacher educationarriccioppoNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Academic Training For Literacy InstructionDocument21 pagesTeachers' Academic Training For Literacy InstructionMULIYANI OLVAHNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 SLA Journal ArticleDocument19 pagesActivity 1 SLA Journal ArticleJecel MontielNo ratings yet

- Is There A Better Time To Focus On FormDocument26 pagesIs There A Better Time To Focus On FormEduardoNo ratings yet

- Multiple Dimensions of Teacher Development On An International PracticumDocument16 pagesMultiple Dimensions of Teacher Development On An International PracticumBruno CoriolanoNo ratings yet

- Sample CHAPTER 1Document10 pagesSample CHAPTER 1Diana Rose CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Teacher Collaboration For English For Specific Purposes in The PhilippinesDocument34 pagesInterdisciplinary Teacher Collaboration For English For Specific Purposes in The PhilippinesKathleen MoradaNo ratings yet

- Llauderes - (For Peer Critiquing) Group 6 III-1 Introduction DraftDocument17 pagesLlauderes - (For Peer Critiquing) Group 6 III-1 Introduction DraftChristina LlauderesNo ratings yet

- GenreDocument21 pagesGenreErika AlNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Proposal FinalDocument11 pagesDissertation Proposal Finalempressryzaligas2No ratings yet

- Group 7Document5 pagesGroup 7Charies VirayNo ratings yet

- Content Based InstructionDocument20 pagesContent Based InstructionAndrey Shauder GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Vorobel (2017) - ECOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE AND FOREIGNDocument8 pagesVorobel (2017) - ECOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE AND FOREIGNEvelyn Margarita Vera FlándezNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal by Irm Students Real Sample 1Document14 pagesResearch Proposal by Irm Students Real Sample 12257011111No ratings yet

- Example Introduction of ParagraphDocument1 pageExample Introduction of ParagraphCharmingers DubMoNo ratings yet

- Unravelling Upper-Secondary School Teachers Beliefs About Language Awareness FroDocument24 pagesUnravelling Upper-Secondary School Teachers Beliefs About Language Awareness FroAmaniNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy (Ies) For Elt in Indonesia: Kasey R. LarsonDocument17 pagesCritical Pedagogy (Ies) For Elt in Indonesia: Kasey R. LarsonThan Rey SihombingNo ratings yet

- Culture Teaching Methods in Foreign Language Education: Pre-Service Teachers' Reported Beliefs and PracticesDocument18 pagesCulture Teaching Methods in Foreign Language Education: Pre-Service Teachers' Reported Beliefs and PracticesDuita DuitaNo ratings yet

- Mother TongueDocument18 pagesMother TonguePanis RyanNo ratings yet

- MultiLiteracies in The Classroom For First Year TeachersDocument22 pagesMultiLiteracies in The Classroom For First Year TeachersRaven FrostNo ratings yet

- Interactions Between Medium of Instruction and Language Learning MotivationDocument15 pagesInteractions Between Medium of Instruction and Language Learning MotivationEce YaşNo ratings yet

- i01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationDocument9 pagesi01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationMuhammad Iwan MunandarNo ratings yet

- A Community of Practice in Teacher Education: Insights and PerceptionsDocument14 pagesA Community of Practice in Teacher Education: Insights and PerceptionscharmaineNo ratings yet

- A Resume of The Practice of Genre-Based Pedagogy in Indonesian SchoolsDocument5 pagesA Resume of The Practice of Genre-Based Pedagogy in Indonesian SchoolsSiti Himatul AliahNo ratings yet

- Language Planning, Ideology and IdentityDocument20 pagesLanguage Planning, Ideology and IdentityJero BovinoNo ratings yet

- Valdez - Critical ELT in Philippines PDFDocument7 pagesValdez - Critical ELT in Philippines PDFJessica AbejaronNo ratings yet

- Opening Minds - KirschDocument35 pagesOpening Minds - KirschNassima BnsNo ratings yet

- English As A Lingua Franca in Teacher EducationDocument17 pagesEnglish As A Lingua Franca in Teacher EducationBruno de AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Content Based Instruction Met 1999Document26 pagesContent Based Instruction Met 1999Susana GuallanoneNo ratings yet

- Bruno Mota - Literature Review Final DraftDocument7 pagesBruno Mota - Literature Review Final DraftBruno AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Freeman 1989 Teacher EducationDocument19 pagesFreeman 1989 Teacher EducationNorbella MirandaNo ratings yet

- Editorial Teaching EALD Learners Across The CurricDocument10 pagesEditorial Teaching EALD Learners Across The CurricRyunjin ShinNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument18 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-547018120No ratings yet

- 3 +ehsan+18-29Document12 pages3 +ehsan+18-29liujinglei3No ratings yet

- The Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationDocument17 pagesThe Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationSoraya GilNo ratings yet

- ELTMD Presentation Group 1Document22 pagesELTMD Presentation Group 1Music LifeNo ratings yet

- 52 Bài Scaffolding 10.1515_iral-2023-0125Document19 pages52 Bài Scaffolding 10.1515_iral-2023-0125Ngọc OanhNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Luis Carabantes LealDocument3 pagesBook Review: Luis Carabantes Lealgodoydelarosa2244No ratings yet

- Competence-Based Teacher Education: A Change From Didaktik To Curriculum Culture?Document28 pagesCompetence-Based Teacher Education: A Change From Didaktik To Curriculum Culture?MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Grammar Teaching and LearningDocument28 pagesGrammar Teaching and LearningPablo García MárquezNo ratings yet

- ESP vs. CLILDocument26 pagesESP vs. CLILKlára BicanováNo ratings yet

- Potential Cultural Resistance To Pedagogical ImportsDocument13 pagesPotential Cultural Resistance To Pedagogical ImportsYan Hao NamNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Content KnowledgeDocument7 pagesPedagogical Content KnowledgeThh TeoNo ratings yet

- The Warwick EltDocument11 pagesThe Warwick EltHamida SariNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness TBI CBI in Teaching VocabDocument19 pagesEffectiveness TBI CBI in Teaching VocabSu HandokoNo ratings yet

- J.S Academic LanguageDocument22 pagesJ.S Academic LanguageMarta FrhbicNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Teacher Ed in Changing Times - TESOLDocument7 pages2010 - Teacher Ed in Changing Times - TESOLmnbvfgtr5432plkjihyuuytyrerNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Esl ScalesDocument3 pagesEvaluation of Esl Scalesapi-287391552No ratings yet

- How Newly Appointed ESL Teachers' Beliefs Are Translated Into Their Pedogogic StretegiesDocument9 pagesHow Newly Appointed ESL Teachers' Beliefs Are Translated Into Their Pedogogic StretegiesDr Irfan Ahmed RindNo ratings yet

- Scaffolding Framework 3 - Pawan 2008 - For Types of Scaffolding (Linguistic)Document13 pagesScaffolding Framework 3 - Pawan 2008 - For Types of Scaffolding (Linguistic)NashwaNo ratings yet

- Teacher Student InteractionDocument22 pagesTeacher Student InteractionAnonymous tKqpi8T2XNo ratings yet

- Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsFrom EverandMultilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- Researching Vocabulary Through A Word Knowledge Framework: Word Associations and Verbal SuffixesDocument20 pagesResearching Vocabulary Through A Word Knowledge Framework: Word Associations and Verbal Suffixesa1dhillon100% (1)

- EBL E-Books For MA ELT StudentsDocument19 pagesEBL E-Books For MA ELT Studentsa1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Reading and Referring To Sources 2013Document31 pagesReading and Referring To Sources 2013a1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Example DisstertationDocument71 pagesExample Disstertationa1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Every Learner MattersDocument2 pagesEvery Learner Mattersa1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Annual Implementation Plan in Math 15-16Document9 pagesAnnual Implementation Plan in Math 15-16Noemie BautistaNo ratings yet

- ESL Listening Comprehension - Practical Guidelines For TeachersDocument3 pagesESL Listening Comprehension - Practical Guidelines For TeacherscristinadrNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 Variant 2 Mark SchemeDocument14 pagesPaper 2 Variant 2 Mark SchemeHusban HaiderNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving StrategiesDocument11 pagesProblem Solving StrategiesLailanie VernizNo ratings yet

- DLP - Straight Lines and Curved Lines and Three - Dimensional Flat Surfaces PDFDocument6 pagesDLP - Straight Lines and Curved Lines and Three - Dimensional Flat Surfaces PDFCrizzel MercadoNo ratings yet

- Ourpages Auto 2012 10-17-57339142 Comp Lab RubricDocument1 pageOurpages Auto 2012 10-17-57339142 Comp Lab RubricgobeyondskyNo ratings yet

- مراجع الفصل 2Document6 pagesمراجع الفصل 2amlarynmhmd5No ratings yet

- Reading Progress ReportDocument2 pagesReading Progress ReportAleona Padoga MalinaoNo ratings yet

- Summary of Kenneth D. Mackenzie and Robert HouseDocument4 pagesSummary of Kenneth D. Mackenzie and Robert HouseDr-Akshay BhatNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Cambridge Bocu Mihali Camelia AlinaDocument3 pagesKindergarten Cambridge Bocu Mihali Camelia AlinaCarmen Delia BocuNo ratings yet

- Trins School BrochureDocument13 pagesTrins School BrochureShameer ShajiNo ratings yet

- English Literature Teacher S Guide UG013031Document78 pagesEnglish Literature Teacher S Guide UG013031Rebecca TsangNo ratings yet

- Carl Lindahl Linda Degh (1918 2014)Document4 pagesCarl Lindahl Linda Degh (1918 2014)vgl1900No ratings yet

- Post RegionalsDocument1 pagePost RegionalsbrownultimateNo ratings yet

- Emergent Curriculum ProjectDocument9 pagesEmergent Curriculum Projectapi-457734928No ratings yet

- Kindergarten Parent Questionnaire 11-12Document4 pagesKindergarten Parent Questionnaire 11-12Diana Moore DíazNo ratings yet

- Land NavigationDocument15 pagesLand NavigationCesar Del CastilloNo ratings yet

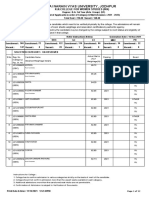

- Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur: K.N.College For Women StudiesDocument12 pagesJai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur: K.N.College For Women StudiesJeevan MaliNo ratings yet

- People CapabilityDocument22 pagesPeople CapabilityShinde SagarNo ratings yet

- Astm101 Cca Cna Soms Ludwikoski s15Document12 pagesAstm101 Cca Cna Soms Ludwikoski s15api-309762706No ratings yet

- Akeli PortfolioDocument97 pagesAkeli PortfolioAlyssa DavidNo ratings yet

- English 6: Let's Identify Them!Document16 pagesEnglish 6: Let's Identify Them!Francis Ann VargasNo ratings yet

- School Guidebook 2013-14-1 PDFDocument230 pagesSchool Guidebook 2013-14-1 PDFarchitectfemil6663No ratings yet

- Philo Chapter 1Document3 pagesPhilo Chapter 1Josh SchultzNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Learnings Part2Document3 pagesAssessment of Learnings Part2MJ Botor50% (2)

- CV Takangeyong KimberlyDocument3 pagesCV Takangeyong KimberlyJunior YuhNo ratings yet

- Roots School SystemDocument9 pagesRoots School SystemNadeem NadeemNo ratings yet

- Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage (Part 1)Document6 pagesTangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage (Part 1)Tsuna DragneelNo ratings yet

Pre-service and Novice Teachers’ Perceptions on Second Language Teacher Education Initial English Language Teacher Education

Pre-service and Novice Teachers’ Perceptions on Second Language Teacher Education Initial English Language Teacher Education

Uploaded by

a1dhillon0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1 views3 pagesPre service perceptions

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentPre service perceptions

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

1 views3 pagesPre-service and Novice Teachers’ Perceptions on Second Language Teacher Education Initial English Language Teacher Education

Pre-service and Novice Teachers’ Perceptions on Second Language Teacher Education Initial English Language Teacher Education

Uploaded by

a1dhillonPre service perceptions

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

14 Initial English Language Teacher Education

In Argentina, as the National Education Act passed in 2006 dictates the

extension of compulsory education to encompass secondary school (Ruiz and

Schoo 2014), educators meet new challenges to cater for diversity and achieve

inclusion. The case of IELTE requires a transition from English Language

Teaching (ELT) for a small elite to the provision of ELT for everyone. In

addition, national language policy (see Banegas 2014; Ibáñez and Lothringer

2013; Porto 2015; Porto, Montemayor-Borsinger and López-Barrios 2016)

advocates a plurilingual and intercultural perspective and a reflective and

research-engaged teaching pedagogy, thus widening the scope of change to be

introduced.

The process of IELTE curriculum reform in Santa Fe, our province, is still

ongoing at the time of writing this chapter. Whereas on the whole this has been

a participatory process involving policy makers, ad hoc specialist committees,

IELTE heads of department and teacher educators in current programmes, in

contrast the voices of students in TEP and those of recent graduates have been

acknowledged perfunctorily or not at all. Yet it falls on them to carry out the

implementation of the curricular change in primary and secondary education,

which has already been put into effect.

The aim of this study is twofold: to explore the beliefs of advanced teacher-

learners and novice English language teachers in Rosario (Santa Fe, Argentina)

regarding the knowledge base of SLTE and to analyse to what extent such beliefs

are congruent with current research on the topic. We believe that the conclusions

can prove a welcome, contextually bound contribution to the curriculum under

construction, as they allow us to glean the strengths and weaknesses of the current

TEP and the demands of classroom teaching. Furthermore, they can contribute

to the body of research on context-specific SLTE curriculum practices, which

Nguyen (2013: 37) characterizes as scarce, though the apparent dearth in this

respect could perhaps be attributed to limited accessibility to publications from

non-central contexts.

A multidimensional conceptualization

of the knowledge base of SLTE

The comprehensive conceptualization of the teaching knowledge base by Shulman

as ‘a codified and codifiable aggregation of knowledge, skill, understanding, and

technology, of ethics and disposition, of collective responsibility’ (1987: 4) sets the

Pre-service and Novice Teachers’ Perceptions on Language Teaching 15

grounds for most of the subsequent research on teacher education. He submits

that the sources for such knowledge are to be found not only in discipline-specific

scholarship, in the materials and settings of the institutionalized educational

processes and in the practice itself, but also in ‘research on schooling, social

organizations, human learning, teaching and development, and the other

social and cultural phenomena that affect what teachers do’ (1987: 8). The

seven seminal categories he proposes (content knowledge, general pedagogical

knowledge, curriculum knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, knowledge

of learners, of contexts and of educational ends, purposes, and values) have been

widely examined with reference to IELTE programmes (e.g. in Latin America in

Álvarez Valencia 2009; Banegas 2009; Fandiño 2013).

The knowledge base of SLTE has been the subject of extensive research in its

own right, with Graves (2009) as a case in point. She sets apart the knowledge

base of SLTE, that is, what the education of language teachers involves, from

the knowledge base of language teaching (LT), which refers to the education

of language learners, though she suggests that both are inextricably linked. She

draws attention to the fact that different conceptualizations of language as well

as the teacher-learners’ identities as L1 or L2 speakers will determine differences

in the curriculum of SLTE and that the rationale for the inclusion of content

should be its relevance to language teaching. Yet she argues, from a sociocultural

perspective, that ‘the issue is not what is relevant in the curriculum but who

makes it relevant, how and why’ (2009: 120).

Also from a sociocultural standpoint, Freeman and Johnson (1998) highlight

the commonalities between the knowledge base for general teacher education

and for SLTE. They focus on the activity of teaching and put forward the

existence of three interrelated domains: the teacher as learner of teaching, the

social context and the pedagogical process. At the crossroads with cognitivism,

they posit that student-teachers’ prior experiences of learning (both in early

schooling and during SLTE) as well as their wants, needs and expectations have

a key role in shaping the knowledge base.

In more recent studies, the contextual dimension has gained prominence.

Johnson (2009: 114) advocates the need to ‘take into account the social, political,

economic and cultural histories that are “located” in the contexts where

L2 teachers learn and teach’ to prevent the imposition of external methods

and recipes, while at the same time challenging local constraints through

engagement with wider professional discourses and practices in processes of

reflective inquiry. In this line, the discussion of the knowledge base of SLTE is

16 Initial English Language Teacher Education

further enriched with the contributions of critical and postmethod pedagogy.

Franson and Holliday (2009: 40), for example, argue for a decentred approach to

‘recognize and explore the cultural complexity and diversity’ within the personal

experiences of teachers and learners, as opposed to an essentialist view of culture

abounding in stereotypes.

Richards (2010) further discusses the notion of context, which he

understands to encompass both structural influences (e.g. school culture,

management style and physical resources available) and personal influences

(including learners, other teachers, even parents). He also delves into two

dimensions of professionalism: one that is institutionally prescribed and refers

to qualifications as well as a commitment to attaining high standards, and

another that is independent and concerns the teachers’ reflection on their own

values, beliefs and practices. After IELTE, he posits, SLTE continues as a process

of socialization in a particular context as the teacher becomes a member of a

community of practice.

The role of socialization experiences, in fact, is another aspect that currently

features prominently in the literature. Farrell (2009) draws attention to the part

they play in the first years of teaching to consolidate teachers’ beliefs about

language teaching and learning. Conway, Murphy and Rath (2009) espouse

the view that learning to teach should occur within a continuum of teacher

education spanning initial, induction and in-service education and development,

and they document a number of countries that have set up quality induction

programmes. The purpose of such programmes is to assist novice teachers to

address the challenges of their early years without being drawn into dominant

practices of the professional context and to strengthen their commitment to

lifelong learning. In order to bridge the gap between SLTE and the realities of

the school classroom where novice teachers take their first steps, a number of

options have been described in Farrell (2015a), all of which revolve around the

need to integrate theory and practice through the development of principled

reflection by teacher-learners and novice teachers.

Yet other directions found in recent analyses refer to the consideration of

changing local circumstances instead of the pursuit of an all-encompassing

static model for the knowledge base of LT to be replicated worldwide. Álvarez

Valencia (2009), for example, postulates the existence of multiple, context-

bound knowledge bases in dialogic interaction, which he illustrates through the

metaphor of an orchestra with the teacher as conductor who, through reflection,

decides what to play and how to play appropriately for a given audience and

You might also like

- A Teacher Guide To Classroom Research PDFDocument237 pagesA Teacher Guide To Classroom Research PDFNoor Dedhy83% (24)

- Task 1 - Teacher Development ReflectionDocument3 pagesTask 1 - Teacher Development ReflectionHarold Bonilla PerezNo ratings yet

- Teaching Vocabulary by Paul NationDocument9 pagesTeaching Vocabulary by Paul Nationanna_elpux20098387100% (1)

- Lola Seaton, The Ends of Criticism, NLR 119, September October 2019 PDFDocument28 pagesLola Seaton, The Ends of Criticism, NLR 119, September October 2019 PDFEnio VieiraNo ratings yet

- Preparing Pre Service Teachers For The SDocument18 pagesPreparing Pre Service Teachers For The SJulian DuqueNo ratings yet

- Empowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyDocument12 pagesEmpowering Non-Native English Speaking Teachers Through Critical PedagogyAngely Chacón BNo ratings yet

- TESOL Quarterly - 2019 - Hennebry Leung - Transitioning From Master S Studies To The Classroom From Theory To PracticeDocument27 pagesTESOL Quarterly - 2019 - Hennebry Leung - Transitioning From Master S Studies To The Classroom From Theory To PracticeNourhanNo ratings yet

- SLA Final Assignment - Research Proposal (Hương - Đô - Liên - Lĩnh)Document38 pagesSLA Final Assignment - Research Proposal (Hương - Đô - Liên - Lĩnh)miniNo ratings yet

- Researching English Language and Literacy Development in SchoolsDocument22 pagesResearching English Language and Literacy Development in Schoolsapi-27788847No ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document22 pagesFULLTEXT01Mig Mony BrownNo ratings yet

- Austtaralian and VietnameseDocument22 pagesAusttaralian and VietnameseeltcanNo ratings yet

- VIERA Task in ClassroomDocument24 pagesVIERA Task in ClassroomjanNo ratings yet

- Tian2020 Promoting Translanguaging in TESOL teacher educationDocument23 pagesTian2020 Promoting Translanguaging in TESOL teacher educationarriccioppoNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Academic Training For Literacy InstructionDocument21 pagesTeachers' Academic Training For Literacy InstructionMULIYANI OLVAHNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 SLA Journal ArticleDocument19 pagesActivity 1 SLA Journal ArticleJecel MontielNo ratings yet

- Is There A Better Time To Focus On FormDocument26 pagesIs There A Better Time To Focus On FormEduardoNo ratings yet

- Multiple Dimensions of Teacher Development On An International PracticumDocument16 pagesMultiple Dimensions of Teacher Development On An International PracticumBruno CoriolanoNo ratings yet

- Sample CHAPTER 1Document10 pagesSample CHAPTER 1Diana Rose CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Teacher Collaboration For English For Specific Purposes in The PhilippinesDocument34 pagesInterdisciplinary Teacher Collaboration For English For Specific Purposes in The PhilippinesKathleen MoradaNo ratings yet

- Llauderes - (For Peer Critiquing) Group 6 III-1 Introduction DraftDocument17 pagesLlauderes - (For Peer Critiquing) Group 6 III-1 Introduction DraftChristina LlauderesNo ratings yet

- GenreDocument21 pagesGenreErika AlNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Proposal FinalDocument11 pagesDissertation Proposal Finalempressryzaligas2No ratings yet

- Group 7Document5 pagesGroup 7Charies VirayNo ratings yet

- Content Based InstructionDocument20 pagesContent Based InstructionAndrey Shauder GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Vorobel (2017) - ECOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE AND FOREIGNDocument8 pagesVorobel (2017) - ECOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE AND FOREIGNEvelyn Margarita Vera FlándezNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal by Irm Students Real Sample 1Document14 pagesResearch Proposal by Irm Students Real Sample 12257011111No ratings yet

- Example Introduction of ParagraphDocument1 pageExample Introduction of ParagraphCharmingers DubMoNo ratings yet

- Unravelling Upper-Secondary School Teachers Beliefs About Language Awareness FroDocument24 pagesUnravelling Upper-Secondary School Teachers Beliefs About Language Awareness FroAmaniNo ratings yet

- Critical Pedagogy (Ies) For Elt in Indonesia: Kasey R. LarsonDocument17 pagesCritical Pedagogy (Ies) For Elt in Indonesia: Kasey R. LarsonThan Rey SihombingNo ratings yet

- Culture Teaching Methods in Foreign Language Education: Pre-Service Teachers' Reported Beliefs and PracticesDocument18 pagesCulture Teaching Methods in Foreign Language Education: Pre-Service Teachers' Reported Beliefs and PracticesDuita DuitaNo ratings yet

- Mother TongueDocument18 pagesMother TonguePanis RyanNo ratings yet

- MultiLiteracies in The Classroom For First Year TeachersDocument22 pagesMultiLiteracies in The Classroom For First Year TeachersRaven FrostNo ratings yet

- Interactions Between Medium of Instruction and Language Learning MotivationDocument15 pagesInteractions Between Medium of Instruction and Language Learning MotivationEce YaşNo ratings yet

- i01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationDocument9 pagesi01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationMuhammad Iwan MunandarNo ratings yet

- A Community of Practice in Teacher Education: Insights and PerceptionsDocument14 pagesA Community of Practice in Teacher Education: Insights and PerceptionscharmaineNo ratings yet

- A Resume of The Practice of Genre-Based Pedagogy in Indonesian SchoolsDocument5 pagesA Resume of The Practice of Genre-Based Pedagogy in Indonesian SchoolsSiti Himatul AliahNo ratings yet

- Language Planning, Ideology and IdentityDocument20 pagesLanguage Planning, Ideology and IdentityJero BovinoNo ratings yet

- Valdez - Critical ELT in Philippines PDFDocument7 pagesValdez - Critical ELT in Philippines PDFJessica AbejaronNo ratings yet

- Opening Minds - KirschDocument35 pagesOpening Minds - KirschNassima BnsNo ratings yet

- English As A Lingua Franca in Teacher EducationDocument17 pagesEnglish As A Lingua Franca in Teacher EducationBruno de AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Content Based Instruction Met 1999Document26 pagesContent Based Instruction Met 1999Susana GuallanoneNo ratings yet

- Bruno Mota - Literature Review Final DraftDocument7 pagesBruno Mota - Literature Review Final DraftBruno AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Freeman 1989 Teacher EducationDocument19 pagesFreeman 1989 Teacher EducationNorbella MirandaNo ratings yet

- Editorial Teaching EALD Learners Across The CurricDocument10 pagesEditorial Teaching EALD Learners Across The CurricRyunjin ShinNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument18 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-547018120No ratings yet

- 3 +ehsan+18-29Document12 pages3 +ehsan+18-29liujinglei3No ratings yet

- The Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationDocument17 pagesThe Routledge Handbook of Translation and EducationSoraya GilNo ratings yet

- ELTMD Presentation Group 1Document22 pagesELTMD Presentation Group 1Music LifeNo ratings yet

- 52 Bài Scaffolding 10.1515_iral-2023-0125Document19 pages52 Bài Scaffolding 10.1515_iral-2023-0125Ngọc OanhNo ratings yet

- Book Review: Luis Carabantes LealDocument3 pagesBook Review: Luis Carabantes Lealgodoydelarosa2244No ratings yet

- Competence-Based Teacher Education: A Change From Didaktik To Curriculum Culture?Document28 pagesCompetence-Based Teacher Education: A Change From Didaktik To Curriculum Culture?MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Grammar Teaching and LearningDocument28 pagesGrammar Teaching and LearningPablo García MárquezNo ratings yet

- ESP vs. CLILDocument26 pagesESP vs. CLILKlára BicanováNo ratings yet

- Potential Cultural Resistance To Pedagogical ImportsDocument13 pagesPotential Cultural Resistance To Pedagogical ImportsYan Hao NamNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Content KnowledgeDocument7 pagesPedagogical Content KnowledgeThh TeoNo ratings yet

- The Warwick EltDocument11 pagesThe Warwick EltHamida SariNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness TBI CBI in Teaching VocabDocument19 pagesEffectiveness TBI CBI in Teaching VocabSu HandokoNo ratings yet

- J.S Academic LanguageDocument22 pagesJ.S Academic LanguageMarta FrhbicNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Teacher Ed in Changing Times - TESOLDocument7 pages2010 - Teacher Ed in Changing Times - TESOLmnbvfgtr5432plkjihyuuytyrerNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Esl ScalesDocument3 pagesEvaluation of Esl Scalesapi-287391552No ratings yet

- How Newly Appointed ESL Teachers' Beliefs Are Translated Into Their Pedogogic StretegiesDocument9 pagesHow Newly Appointed ESL Teachers' Beliefs Are Translated Into Their Pedogogic StretegiesDr Irfan Ahmed RindNo ratings yet

- Scaffolding Framework 3 - Pawan 2008 - For Types of Scaffolding (Linguistic)Document13 pagesScaffolding Framework 3 - Pawan 2008 - For Types of Scaffolding (Linguistic)NashwaNo ratings yet

- Teacher Student InteractionDocument22 pagesTeacher Student InteractionAnonymous tKqpi8T2XNo ratings yet

- Multilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsFrom EverandMultilingualism and Translanguaging in Chinese Language ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- Researching Vocabulary Through A Word Knowledge Framework: Word Associations and Verbal SuffixesDocument20 pagesResearching Vocabulary Through A Word Knowledge Framework: Word Associations and Verbal Suffixesa1dhillon100% (1)

- EBL E-Books For MA ELT StudentsDocument19 pagesEBL E-Books For MA ELT Studentsa1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Reading and Referring To Sources 2013Document31 pagesReading and Referring To Sources 2013a1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Example DisstertationDocument71 pagesExample Disstertationa1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Every Learner MattersDocument2 pagesEvery Learner Mattersa1dhillonNo ratings yet

- Annual Implementation Plan in Math 15-16Document9 pagesAnnual Implementation Plan in Math 15-16Noemie BautistaNo ratings yet

- ESL Listening Comprehension - Practical Guidelines For TeachersDocument3 pagesESL Listening Comprehension - Practical Guidelines For TeacherscristinadrNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 Variant 2 Mark SchemeDocument14 pagesPaper 2 Variant 2 Mark SchemeHusban HaiderNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving StrategiesDocument11 pagesProblem Solving StrategiesLailanie VernizNo ratings yet

- DLP - Straight Lines and Curved Lines and Three - Dimensional Flat Surfaces PDFDocument6 pagesDLP - Straight Lines and Curved Lines and Three - Dimensional Flat Surfaces PDFCrizzel MercadoNo ratings yet

- Ourpages Auto 2012 10-17-57339142 Comp Lab RubricDocument1 pageOurpages Auto 2012 10-17-57339142 Comp Lab RubricgobeyondskyNo ratings yet

- مراجع الفصل 2Document6 pagesمراجع الفصل 2amlarynmhmd5No ratings yet

- Reading Progress ReportDocument2 pagesReading Progress ReportAleona Padoga MalinaoNo ratings yet

- Summary of Kenneth D. Mackenzie and Robert HouseDocument4 pagesSummary of Kenneth D. Mackenzie and Robert HouseDr-Akshay BhatNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten Cambridge Bocu Mihali Camelia AlinaDocument3 pagesKindergarten Cambridge Bocu Mihali Camelia AlinaCarmen Delia BocuNo ratings yet

- Trins School BrochureDocument13 pagesTrins School BrochureShameer ShajiNo ratings yet

- English Literature Teacher S Guide UG013031Document78 pagesEnglish Literature Teacher S Guide UG013031Rebecca TsangNo ratings yet

- Carl Lindahl Linda Degh (1918 2014)Document4 pagesCarl Lindahl Linda Degh (1918 2014)vgl1900No ratings yet

- Post RegionalsDocument1 pagePost RegionalsbrownultimateNo ratings yet

- Emergent Curriculum ProjectDocument9 pagesEmergent Curriculum Projectapi-457734928No ratings yet

- Kindergarten Parent Questionnaire 11-12Document4 pagesKindergarten Parent Questionnaire 11-12Diana Moore DíazNo ratings yet

- Land NavigationDocument15 pagesLand NavigationCesar Del CastilloNo ratings yet

- Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur: K.N.College For Women StudiesDocument12 pagesJai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur: K.N.College For Women StudiesJeevan MaliNo ratings yet

- People CapabilityDocument22 pagesPeople CapabilityShinde SagarNo ratings yet

- Astm101 Cca Cna Soms Ludwikoski s15Document12 pagesAstm101 Cca Cna Soms Ludwikoski s15api-309762706No ratings yet

- Akeli PortfolioDocument97 pagesAkeli PortfolioAlyssa DavidNo ratings yet

- English 6: Let's Identify Them!Document16 pagesEnglish 6: Let's Identify Them!Francis Ann VargasNo ratings yet

- School Guidebook 2013-14-1 PDFDocument230 pagesSchool Guidebook 2013-14-1 PDFarchitectfemil6663No ratings yet

- Philo Chapter 1Document3 pagesPhilo Chapter 1Josh SchultzNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Learnings Part2Document3 pagesAssessment of Learnings Part2MJ Botor50% (2)

- CV Takangeyong KimberlyDocument3 pagesCV Takangeyong KimberlyJunior YuhNo ratings yet

- Roots School SystemDocument9 pagesRoots School SystemNadeem NadeemNo ratings yet

- Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage (Part 1)Document6 pagesTangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage (Part 1)Tsuna DragneelNo ratings yet