Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Use_of_the_Theoretical_Domains_Framework_to_evalua

Use_of_the_Theoretical_Domains_Framework_to_evalua

Uploaded by

Lukas ArenasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Use_of_the_Theoretical_Domains_Framework_to_evalua

Use_of_the_Theoretical_Domains_Framework_to_evalua

Uploaded by

Lukas ArenasCopyright:

Available Formats

Skoien et al.

Implementation Science (2016) 11:136

DOI 10.1186/s13012-016-0500-9

RESEARCH Open Access

Use of the Theoretical Domains Framework

to evaluate factors driving successful

implementation of the Accelerated Chest

pain Risk Evaluation (ACRE) project

Wade Skoien1, Katie Page2, William Parsonage1, Sarah Ashover1, Tanya Milburn1 and Louise Cullen1*

Abstract

Background: The translation of healthcare research into practice is typically challenging and limited in

effectiveness. The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) identifies 12 domains of behaviour determinants which

can be used to understand the principles of behavioural change, a key factor influencing implementation. The

Accelerated Chest pain Risk Evaluation (ACRE) project has successfully translated research into practice, by

implementing an intervention to improve the assessment of low to intermediate risk patients presenting to

emergency departments (EDs) with chest pain. The aims of this paper are to describe use of the TDF to determine

which factors successfully influenced implementation and to describe use of the TDF as a tool to evaluate

implementation efforts and which domains are most relevant to successful implementation.

Methods: A 30-item questionnaire targeting clinicians was developed using the TDF as a guide. Questions

encompassed ten of the domains of the TDF: Knowledge; Skills; Social/professional role and identity; Beliefs about

capabilities; Optimism; Beliefs about consequences; Intentions; Memory, attention and decision processes; Environmental

context and resources; and Social influences.

Results: Sixty-three of 176 stakeholders (36 %) responded to the questionnaire. Responses for all scales showed

that respondents were highly favourable to all aspects of the implementation. Scales with the highest mean

responses were Intentions, Knowledge, and Optimism, suggesting that initial education and awareness strategies

around the ACRE project were effective. Scales with the lowest mean responses were Environmental context and

resources, and Social influences, perhaps highlighting that implementation planning could have benefitted from

further consideration of the factors underlying these scales.

Conclusions: The ACRE project was successful, and therefore, a perfect case study for understanding factors which

drive implementation success. The overwhelmingly positive response suggests that it was a successful programme

and likely that each of these domains was important for the implementation. However, a lack of variance in the

responses hampered us from concluding which factors were most influential in driving the success of the

implementation. The TDF offers a useful framework to conceptualise and evaluate factors impacting on

implementation success. However, its broad scope makes it necessary to tailor the framework to allow evaluation of

specific projects.

Keywords: Implementation science, Research translation, Theoretical domains framework, Behaviour change, Low

and intermediate risk chest pain

* Correspondence: louise.cullen@health.qld.gov.au

1

Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Butterfield St & Bowen Bridge Rd,

Herston, QLD 4006, Australia

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

© 2016 The Author(s). Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0

International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to

the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver

(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 2 of 11

Background patients presenting with chest pain to emergency depart-

The translation of healthcare research into practice is ments (EDs). The project translates high-quality evidence

typically slow, challenging, and often fails. Only 14 % of from research conducted by our group and published in

published research is translated into bedside practice to 2012 [13], into effective clinical practice. The 2-Hour

the benefit of patients and takes an average time of Accelerated Diagnostic Protocol to Assess Patients with

17 years to occur [1, 2]. There is increasing pressure to Chest Pain Symptoms Using Contemporary Troponins as

translate findings from research into positive health out- the Only Biomarker (ADAPT) trial, was a large retrospect-

comes in a shorter timeframe [3–5], driven partly by the ive observational study which tested whether an ADP for

decrease in research funding availability [6]. The quality patients presenting with possible cardiac chest pain, could

of the evidence behind a new intervention is only one safely identify low-risk patients that were suitable for early

factor that influences successful translation into practice. discharge. The ADAPT-ADP uses the Thrombolysis in

Factors across multiple levels of healthcare from the indi- Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) score, electrocardiography

vidual patient and clinician to the organisational and pol- and 0 and 2-h values of laboratory troponin I to identify

icy levels also require consideration [7]. The research- these low-risk patients. The ADAPT-ADP safely identified

practice gap has led to increased focus on implementation 20 % of patients as low risk and suitable for early dis-

science, which aims to improve the uptake of research charge from the ED. Given that chest pain accounts for a

findings and evidence-based practice (EBP) into routine significant proportion of all ED presentations and has a

practice, to improve the quality and effectiveness of health high hospital admission rate, accelerating the care for

care and services [8]. 20 % of this cohort may reduce burden on the healthcare

Implementation science is a fast growing discipline. system [13]. A successful, single site pilot study took place

The methods are still young and the theories heteroge- in 2013 [14], in which similar results to the ADAPT trial

neous and the practical application relatively sparse. were achieved in practice. In an approximately 2.5-year

Embedding evidence into practice is not a linear or period following this, from 2013 to 2016, 21 suitable target

technical process that can be achieved by individual hospitals (determined by the availability of an on-site

clinical champions alone. Evidence shows implementa- pathology laboratory for laboratory-based troponin test-

tion requires whole system change involving both the ing) were engaged on a site-by-site basis. Key stakeholders

individual and organisation [9]. Theoretical frameworks at each site were initially invited to attend introductory

can help explain why implementation efforts succeed meetings and discussions about the ACRE project and

or fail [5], but the biggest challenge influencing the im- possible implementation of the ADAPT-ADP in their hos-

plementation of new interventions is behaviour change, pital. The ADAPT-ADP is utilised primarily in the ED,

with many frameworks therefore focussing on human and therefore, engagement of senior ED clinicians to work

behaviour theories [10–12]. Traditionally, implementa- with the project team in implementing the ADAPT-

tion efforts have been based on interventions that are ADP at each site was essential. However, support from

intuitive or educational in nature, such as printed edu- other clinicians that manage patients presenting with

cation materials, audit and feedback and reminders. chest pain, such as from cardiology, general medicine

However, these only have a modest effect on changing and clinical measurements departments were essential

clinical practice and could be improved on by consider- to implementation, as each site had different processes,

ing theories of human behaviour [12]. The Theoretical capabilities and resources for managing and following

Domains Framework (TDF) developed by Michie et al. up patients with possible cardiac chest pain, which

[12] used expert consensus to identify 12 domains of influenced how changes to practice would be made.

behaviour determinants that could be used in imple- The development and modification of clinical decision

mentation research. Cane et al. [10], who validated and pathways to incorporate the ADAPT-ADP into local prac-

refined the TDF, also agree that understanding the tice was a key step in implementation that required input

principles of behavioural change and changing the be- and agreement across these multiple disciplines. Funding

haviours of healthcare professionals is the key factor in was obtained to allow for the employment of several part-

implementation efforts, but are rarely considered when time clinical leads and project officers to drive this imple-

designing and evaluating implementation interventions. mentation of the ADAPT-ADP state-wide.

The Accelerated Chest pain Risk Evaluation (ACRE) Nineteen of the 21 suitable target hospitals have im-

project has implemented a new intervention and trans- plemented the ADAPT-ADP and adopted new practice

lated research into practice in a much shorter timeframe in the management of low-intermediate-risk chest pain

than traditionally reported. The ACRE project is a state- patients. Time taken to implement from introductory

wide clinical redesign project in Queensland, Australia, meetings to the use of the pathway in practice varied

implementing an accelerated diagnostic protocol (ADP) from approximately 3 months to greater than 12 months.

to improve the assessment of low to intermediate risk Greater than 20 % of ED patients presenting with chest

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 3 of 11

pain have been identified as low risk and managed accord- be more applicable in developing a TDF-based question-

ing to the accelerated arm of the ADAPT-ADP state-wide. naire (Huijg ref ). We then drew on the interview ques-

This closely matches the proportion demonstrated in the tions and domains used by Curran et al. [18], to add to

original research and pilot site. Comparison of data pre- and refine the questions, as there were similarities in the

and post-implementation has demonstrated that use of intervention they described to the ACRE implementa-

the ADAPT-ADP in widespread practice has significantly tion project. These include the assessment of implemen-

decreased total hospital length of stay (by 33.4 %, from tation outcomes using the TDF post-implementation; the

1210 to 806 mins), decreased ED length of stay (from 230 intervention was implementing a ‘clinical decision rule’;

to 213 mins), and decreased admission rates to inpatient and the change efforts were also in emergency depart-

units (by 13.1 %, from 70.4 to 57.3 %) for all patients with ments. One domain was subsequently excluded from

possible cardiac chest pain [15], which represents approxi- our questionnaire—Emotion, as we did not think the

mately 6 % of all ED presentations [16]. example questions from Huijg et al. [17] relevant in our

The ACRE project has successfully demonstrated im- questionnaire. Curran et al. [18] used this domain; how-

plementation outcomes and translation of research into ever, they determined that this was not one of the domains

practice. However, whilst a coordinated plan was devel- likely to explain physician response to implementation of

oped to implement the intervention, the design could their clinical decision rule. Finally, questions were adapted

be described as one based on ‘intuition’ rather than the- to address factors that we believed were relevant to the

ory, which can limit the understanding of behaviour implementation of our project, based on the ACRE team

change processes that underlie effective interventions beliefs or from informal stakeholder feedback. Three ques-

[10]. Therefore, this paper uses a validated theoretical tions under each of the domains were chosen to be

framework to determine which factors influencing be- included in the final survey, except the domains Environ-

haviours successfully influenced implementation to mental context and resources and Intentions which had

help inform future translational projects, an area that is four and two questions, respectively, as this reflected the

typically challenging and with a high failure rate. The questions deemed most relevant to the implementation of

second aim of this paper is to further describe the use the ACRE project. The scale reliabilities for the ten TDF

of the TDF as a tool to evaluate implementation efforts scales were explored using Cronbach’s alpha, which pro-

and add to the limited available evidence and testing on vides the lower-bound estimate of the reliability of a test/

which domains and scales are most relevant to success- measure. Relationships between the scales were explored

ful implementation. using Pearson correlation coefficients.

The questionnaire also asked the participants to indi-

Methods cate their employment site, and their professional group

This study was an effectiveness-implementation hybrid (i.e. medical, nursing or other, e.g. allied health). For ease

study, performed during a large-scale redesign project of of completion, and to encourage more respondents to

assessment processes for emergency patients with pos- complete the questionnaire, all questions were assessed

sible acute coronary syndromes. The state-wide redesign using a Likert-scale response of 1 (strongly disagree) to

project was conducted across 19 hospitals from October 5 (strongly agree), with space for additional comments

2013 to June 2016, with the implementation research (see Additional file 1).

conducted from October 2015 to December 2015. To test for differences in the scales on key variables (e.g.

time since implementation, hospital size, staff groups), we

Questionnaire development used both repeated measures t tests with Bonferroni

A 30-item questionnaire targeting clinicians was devel- corrections and one-way ANOVAs.

oped using the TDF as a guide (Table 1). The questions

encompass ten of the domains of the TDF. As a starting Participants

point, generic questions were taken from Huijg et al. Questionnaires were distributed to clinician stakeholders

[17] who used the consensus opinion of 19 academic who attended an ACRE project forum held in Brisbane in

judges to allocate questions to TDF domains and tested October 2015. Due to the staggered implementation

the discriminant content validity of each item to ensure across Queensland, timeframes from respondents imple-

it measured the intended domain. The final, generic menting the ADAPT-ADP at their sites and completing

questionnaire they developed included questions under the questionnaire vary markedly. Additionally, in Novem-

11 of the 14 domains described by Cane at al. [10], and ber 2015, questionnaires were also mailed with a return

three domains were excluded as their study did not envelope to other clinician stakeholders that had varying

demonstrate discriminant content validity of the items levels of involvement in the ACRE project. This included

measuring those domains (Huijg ref ). They also state stakeholders that were identified by either their presence

that the 12-domain, original version of the TDF might at initial introductory meetings and discussions about the

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 4 of 11

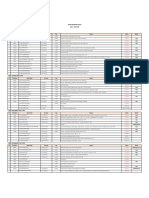

Table 1 Implementation evaluation questions, TDF domains Table 1 Implementation evaluation questions, TDF domains

and descriptive statistics for the questionnaire items and descriptive statistics for the questionnaire items (Continued)

Domain Question Means (SDs) the time and effort required

Knowledge 1 I know the objectives 4.62 (0.52) to adopt it

of the ACRE project Intentions 19 I intend to use the ACRE 4.65 (0.53)

2 The evidence that 4.56 (0.62) pathway when appropriate

supports the ACRE to assess patients presenting

pathway is strong with chest pain

3 I am aware of how the 4.69 (0.59) 20 I intend to promote the 4.71 (0.49)

ACRE pathway is used in education of future staff to

my hospital utilise the ACRE pathway

Skills 4 The skills required to use 4.63 (0.58) Memory, attention 21 Information in my workplace 4.30 (0.76)

the ACRE pathway are and decision is useful to remind me to use

within the scope of an processes the ACRE pathway

ED clinician 22 Assessing a patient with 4.40 (0.79)

5 The ACRE pathway is 4.45 (0.65) chest pain triggers me to

simple to use use the ACRE pathway

6 A junior ED doctor would 4.16 (0.86) 23 If ACRE pathway letters 4.27 (0.66)

have the capabilities to and referrals are easily

apply the ACRE pathway accessible I remember to

to a patient presenting use them

with chest pain Environmental 24 The ACRE pathway is able 4.42 (0.65)

Social/professional 7 Use of the ACRE pathway 4.35 (0.79) context and to be adapted to local

role and identity as a clinical decision rule is resources processes

sound professional practice 25 There has been sufficient 3.91 (0.96)

in the ED local clinician time allocated

8 Having both ED and 4.45 (0.78) to implement the ACRE

Cardiology specialists pathway and processes

leading the ACRE project 26 There are good networks 4.13 (0.85)

has helped improve between parties involved in

acceptance of the project the adoption of the ACRE

by local clinicians project

9 Clinicians from departments 4.21 (0.69) 27 Support from the ACRE project 4.40 (0.68)

that manage patients with team has been integral to the

chest pain support the successful implementation of

introduction of the ACRE the ACRE project

project

Social influences 28 Most people whose opinion I 4.37 (0.71)

Beliefs about 10 It is easy to utilise the ACRE 4.28 (0.67) value would support the ACRE

capabilities pathway when the ED is busy project

11 The criteria of the ACRE 4.56 (0.56) 29 My colleagues are supportive 4.34 (0.73)

pathway are clear to me of the ACRE project

12 I am confident I could apply 4.58 (0.53) 30 Existing staff provide sufficient 4.12 (0.76)

the ACRE pathway to risk support to new staff to use the

stratify a patient presenting ACRE pathway

to ED with chest pain

Optimism 13 I expect positive outcomes 4.48 (0.67)

from the ACRE project

project; were introduced to the project during the imple-

mentation phase due to their clinical role; had a role in

14 I expect ACRE practices to 4.46 (0.57)

be sustained beyond the implementing or educating on its introduction and use

completion of the ACRE locally; or were senior and executive level clinicians who

project were regularly included in correspondence about the pro-

15 Overall, the ACRE project 4.66 (0.54) gress of the ACRE project at their site. This meant that we

represents a positive change sent out a large number of questionnaires in the hope of

for Queensland Health

getting a greater number and wider variety of responses,

Beliefs about 16 The ACRE project improves 4.57 (0.59)

consequences patient flow

but potentially that the response rate would be lower as it

was sent to people without a high level of direct engage-

17 The ACRE project has improved 4.43 (0.65)

management of patients ment with the project. Two weeks after sending out the

presenting with chest pain mailed questionnaires, stakeholders received a reminder

18 The benefits from outcomes of 4.56 (0.59) email to complete the survey, which included a link and

the ACRE project will outweigh the option to complete an online version of the survey. A

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 5 of 11

final reminder email was sent one more week after this. All scales were shown to possess very good reliability

The chance to win one of three $50 gift cards was (above 0.80 for seven scales and above 0.70 for three

offered as incentive for those that returned the scales), and therefore, all items were combined into the

mailed or online questionnaire. Questionnaires were appropriate ten scales for further analysis. Table 3 shows

completed anonymously. the means, standard deviations and reliability statistics

for the ten scales.

The means for all scales show that, on average, the

Results respondents are highly favourable to all aspects of the

Sixty-three of 176 clinician stakeholders (36 %) responded implementation. The Social influences scale shows the

to the questionnaire (25 from 31 forum attendees; 33 most variability and the lowest mean but still highly rela-

mailed and 5 online returns from 145) (see Additional file tive to the scale limits. The Intentions scale has the

2). Whilst the overall response rate was low, the number highest mean and lowest amount of variation in re-

of responses is enough for our purposes. Nineteen hospital sponses, indicating that intentions to use and promote

sites were represented by respondents, nine that had the ACRE pathway was very high in the sample. The

implemented the ACRE pathway for more than 12 months scale of Social/professional role and identity shows the

and ten that had implemented the ACRE pathway for less lowest reliability with both the Optimism and Beliefs

than 12 months and includes two sites that have not im- about capabilities scales possessing the highest reliabil-

plemented at time of survey but have been introduced to ities. All told, these data demonstrate that the instru-

project and planning stages. Respondent characteristics ment is reliable and that the items for each scale are

are listed in Table 2. measuring similar and related constructs. This provides

Table 1 also displays the means and standard devia- support to the items and scales proposed by Huijg et

tions for all 30 items averaged across all participants. al. [17]. Correlations between the ten scales were mod-

Responses to all questions were highly positive with erate to high, with most above 0.6. The Skills scale was

small variance. Participants felt that they had the requis- least related to the others with lower bivariate

ite knowledge and skills to implement the pathway in correlations in the range of 0.26 to 0.5. The Intentions

addition to it being within their professional identify and scale was the one most highly correlated to all of the

believing that the consequences would be positive. There others (range 0.66 to 0.75).

are high levels of optimism for the ACRE project and thus These ten scales were then used to look at differences

intentions around implementation were very high. The in three key areas: (1) hospital staff, (2) time since imple-

three items with the lowest means (Q25, Q26, and Q30) mentation and (3) hospital size/type. Specifically, we

highlight that perhaps one area for improvement could be tested if there were differences in responses to the 10

the allocation of more resources and time locally to ensure TDF scales between hospital sites that had implemented

the successful implementation. the ACRE pathway for more than 12 months versus

those that had implemented the pathway for less than

12 months. There were no significant differences in 9 of

Table 2 Survey respondent characteristics

Time post-implementation More than 12 months = 43 (68 %)

Less than 12 months =20 (32 %) Table 3 Descriptive statistics for the ten scales of the TDF

Professional group Medical = 29 (46 %) Scale (# Qs) Mean (range) SD Scale reliability (α)

Nursing = 29 (46 %) Knowledge (3) 4.61 (3–5) 0.49 0.76

Other/allied health = 5 (8 %) Skills (3) 4.42 (2.67–5) 0.60 0.83

Hospital size/type Major metropolitan = 30 (48 %) Social/professional role and 4.34 (2.67–5) 0.60 0.71

Major regional = 23 (36 %) identity (3)

Large metropolitan = 7 (11 %) Beliefs about capabilities (3) 4.47 (3–5) 0.53 0.87

Medium sized = 3 (5 %) Optimism (3) 4.53 (3–5) 0.53 0.87

Major metropolitan metropolitan hospitals with greater than 20,000 acute Beliefs about consequences (3) 4.51 (3–5) 0.54 0.83

casemix-adjusted separations and greater than 20,000 emergency department Intentions (2) 4.69 (3–5) 0.47 0.83

presentations annually, Major Regional regional hospitals with greater than

16,000 acute casemix-adjusted separations and greater than 20,000 emergency Memory, attention and decision 4.30 (2.67–5) 0.65 0.80

department presentations annually, Large metropolitan metropolitan acute processes (3)

hospitals treating greater than 10,000 acute casemix-adjusted separations and

greater than 20,000 emergency department presentations annually, Medium Environmental context and 4.23 (2.5–5) 0.62 0.81

sized medium acute hospitals in metropolitan and regional areas treating resources (4)

between 5000 and 10,000 acute casemix-adjusted separations and greater Social influences (3) 4.23 (2–5) 0.68 0.75

than 20,000 emergency department resentations annually [19]

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 6 of 11

the 10 scales for these two groupings of hospitals. How- Skills

ever, there was a significant difference in the Social in- Responses in the Skills scale indicated that clinicians

fluences scale between hospitals and implementation find the ACRE pathway simple to use, and they also

time, t(59) = −2.56, p = 0.014, suggesting that staff re- believe their colleagues will find it simple to use. We

ported receiving greater social support for the ACRE believe that a key factor influencing successful imple-

project in hospitals where the implementation had been mentation of the ACRE pathway is that it is simple to

in place for longer than 12 months. use in practice and is an adaptation, rather than re-

We also tested for differences in professional group and placement, of current pathways and guidelines com-

found no significant differences between nursing and monly in use throughout Queensland. A comment

medical staff for any of the ten scales. Allied health highlighting the ease of use in response to Q6 was ‘All

workers were tested as a separate group in one set of ana- they need to do is use the available resources—they are

lyses but because of the small sample size they were then readily available and clear to understand. If they read

grouped with nursing staff and analysis re-run. This made the step-by-step process, they can’t go wrong’.

no difference to the conclusions. Hospitals were grouped

according to size and location as per the Australian Insti-

tute of Health and Welfare hospital peer group codes Social/professional role and identity

(major metropolitan, major regional, large metropolitan, Although the Social/professional role and identity

large regional, and medium) [19]. However, we found scale had a high mean response, some respondents’

there were no significant differences in responses as a comments provided insight into one of the potential

function of hospital type to any of the ten scales. barriers influencing successful implementation—the

different levels of engagement and enthusiasm be-

tween different medical specialties to implement the

Discussion project locally. Some examples include ‘Essential to

The translation of the ADAPT-ADP into clinical practice have support of both teams’, ‘Minimal engagement

by the ACRE project was successful and is therefore a per- from cardiology…’, ‘Need to improve links with cardi-

fect case study for understanding factors which are import- ology team very much an ED project only…’, and ‘Little

ant in driving implementation success. In some ways, the input locally from my in-patient colleagues…’. Whilst

lack of variance in the responses hampered us from con- the ACRE project is very much an ‘ED pathway’, input

cluding which factors were really driving the success for the and support from other relevant departments such as

implementation. However, the overwhelmingly positive re- Cardiology, General Medicine, and Clinical Measure-

sponse also indicates that it was a successful programme ments was essential to ensure patient flow and ad-

and likely a combination of the factors that drove its suc- equate follow-up processes beyond the ED episode of

cess. Given the very high means, we can conclude that each care. Anecdotally, sites that had good engagement and

of these domains was important for the implementation. relationships across departments reported easier im-

plementation and earlier success than sites that did

not. Early ACRE project meetings at sites aimed to in-

Knowledge clude as many relevant departments and people as

The Knowledge scale had the second highest mean re- possible, to help create a shared vision and collabor-

sponse and second least amount of variation in the re- ation. However, it is possible that other departments

sponses. This indicates that knowledge and awareness of did just not feel the same level of commitment to im-

the ACRE project objectives, supporting evidence behind plementation of an ‘ED pathway’ or to prioritise it.

the pathway, and how the pathway is used in practice was Some respondent comments also demonstrated some

strong. A key early step of introducing the ACRE project ambiguity around the interpretation of Q8, ‘Having both

to each site was an education session describing the ED and Cardiology specialists leading the ACRE project

evidence base, as well as practical considerations of imple- has helped improve acceptance of the project by local

menting the ACRE pathway at their hospital. Implementa- clinicians’. The question related to the clinical leads of the

tion efforts require consideration of factors beyond ACRE project, whereas some respondents clearly an-

education strategies though, as Curran et al. [18] describe swered this question in relation to their local ED and

high levels of knowledge of the evidence and benefits be- Cardiology specialists that were engaged as stakeholders

hind the clinical decision rule they implemented, yet at their sites. This might have affected the results or the

actual use in practice was low. However, ensuring high scale reliability, but it is unclear how many responded in

levels of knowledge still remains a vital step in implement- this way. This shows how comments can be useful to

ing a new intervention and survey responses indicate that identify ambiguous questions which could be revised if

the ACRE project successfully did this. the questionnaire was used again.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 7 of 11

Beliefs about capabilities implementation efforts need to create this vision and

The Beliefs about capabilities scale showed that clini- belief that the work is worth doing, or implementation

cians were positive about their ability to use the ACRE may fail, even when there is value in doing it [20].

pathway in practice. Interestingly, Q10 (‘It is easy to util-

ise the ACRE pathway when the ED is busy’) had a Intentions

slightly lower mean response than the other questions in The Intentions scale had the highest mean response and

this scale. A point was highlighted in Curran et al. [18] demonstrated the high intentions of respondents to both

about conflicting views on whether use of their clinical use the ACRE pathway and promote use and education

decision rule actually improved or slowed patient flow to future staff. For example, ‘I will continue to promote

through the ED when the department was busy. This pathway to our medical team’. This is positive feedback,

might have also been relevant for the ACRE project, as as a person’s intentions are a strong predictor of behav-

one respondent stated, ‘Really depends on how ‘busy’ iour [21]. However, predicting behaviours from inten-

and what time of day…’. Despite the ACRE pathway tions are also influenced by other factors such as social

being identified as simple to use and time saving, the pressure [22] and therefore likely that ‘Intentions’ would

extra thought processes to do something differently be influenced by other domains in attempting to explain

when it is busy and with multiple competing priorities successful implementation and use of the pathway in

may mean it is easier to revert back to previous standard practice.

practice. An important part of ensuring projects like this

are implemented is making sure that the process is easy Memory, attention and decision processes

to follow and not complicated, or clinicians may revert The Memory, attention and decision processes scale

back to standard practice that is already familiar. Fur- showed high responses; however, the mean response in

thermore, there was a slightly higher mean response to this domain was lower than that in the Intentions do-

this question in sites that had implemented the ACRE main. This suggests that despite high intentions to use a

pathway for >12 months versus <12 months, perhaps in- new pathway or decision-making tool in practice, it

dicating that once the pathway is established and has needs to be easy to use and easily accessible to promote

become normal practice, it is easier to use when busy. use. Steps taken to achieve this included local project

officers or engaged stakeholders at sites providing edu-

Optimism cation, placing posters up, and ensuring that the path-

The Optimism scale had the third highest mean re- ways and associated documents were available and easily

sponse and demonstrated that optimism around the accessible. To promote use of the pathway at one site, it

ACRE project outcomes and sustainability in practice was placed with chest pain patients as soon as they ar-

was high and therefore likely contributed as a positive rived in ED by the triage nurse. This idea was shared

factor influencing successful implementation. High levels with other sites, some of which also adopted this

of optimism around the project could relate back to a approach and reported improved use of the pathway. It

strong evidence base, positive outcomes achieved in the remains a challenge though, as several comments high-

pilot study, and positive outcomes achieved in practice light, ‘One of the acknowledged challenges in a depart-

at their own sites, as well as optimism about sustaining ment full of forms and paperwork is having the

it in practice. Clinicians may have also reported high paperwork stand out’ and ‘Need to maintain availability

levels of optimism as the ACRE pathway targets clinical as new staff members join team’. This may improve once

redesign in a high-volume patient group and is therefore the new intervention has been in place for a period of time

more likely to improve efficiency and produce ‘quick and is embedded into usual practice though, as mean

wins’ in high profile problem areas facing EDs such as responses for questions in this domain were slightly higher

patient flow and access and release capacity back into in sites that had implemented for >12 months. As

the system [20]. one respondent commented, ‘Is already well ingrained

in practice’.

Beliefs about consequences

Responses to questions in the scale Beliefs about conse- Environmental context and resources

quences indicate that clinicians not only believe that the The Environmental context and resources scale had the

ACRE pathway improves patient flow and management equal lowest mean response. It included questions about

of patients with possible cardiac chest pain, but also that external factors we thought were likely to influence im-

the benefits from outcomes of the ACRE project will plementation. Q24 examined one of the features that we

outweigh the time and effort required to adopt it (Q18). felt was a key factor influencing successful implementa-

This is important, as there will be efforts and inevitable tion, especially across many different sites, flexibility of

challenges involved when implementing change. All the pathway and adapting it to fit with local processes

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 8 of 11

and preferences, rather than a standard approach to im- lag time before the ‘early majority’ and then the ‘late

plementation across all sites. This may also help explain majority’ supports or adopt a new innovation [25]. This

why there was no significant difference in responses scale also links to a factor that we believe contributed to

between stakeholders by hospital size and type. The hos- success—the order in which sites were approached to

pitals that have implemented the pathway vary widely, implement the project. There were several sites we felt

from major metropolitan hospitals with cardiology de- would be more receptive to implementation and more

partments to medium-sized and regional hospitals with- likely to be engaged with the project team than others,

out any internal cardiology services for following up for example, sites that approached us to express interest

patients. Adaptability of an intervention to suit the local in the project or, simply based on our own perceptions

environment has been shown to be an important factor of sites that may more readily implement change in this

influencing implementation [23, 24]. Tailoring the ACRE field, from knowledge working within the organisation.

pathway to fit local practice, for example, flexibility with These sites were targeted first to try and achieve early

outpatient and follow up processes, helped enable success. This helped garner momentum for the project

successful implementation across multiple different sites. and drive implementation at subsequent sites, who may

Questions 25 and 26 explored if respondents felt that have also felt pressure to implement once other peer or

there had been sufficient local clinician time allocated to competing hospitals had already implemented [26].

implement the ACRE pathway and processes and if there The item with the second lowest mean score overall

are good networks between parties involved in the adop- was Q30, ‘Existing staff provide sufficient support to new

tion of the ACRE project. Expectedly, these questions staff to use the ACRE pathway’. Two comments further

had lower mean responses than the majority of ques- highlighted this challenge, ‘Orientation of new ED staff is

tions, and Q25 was the item with the lowest mean score very challenging given: large number of processes across

overall. Whilst most organisations would agree that multiple areas need to be included, this is just one; no

evidence-based innovative changes to practice that pro- single orientation time for all new staff given shift work;

duce positive outcomes are beneficial, it may be more orientation once appears insufficient; staff need to be

difficult to achieve in practice without the available re- supported on floor when initially using the pathway in

sources, especially around staffing availability. The order to avoid basic errors…’ and ‘Our department has

ACRE project offered a limited amount of funding to multiple part-time senior clinicians and a very transient

sites to support a local clinician (e.g. for the provision of SHO/RMO group—challenges in keeping the message

offline time, or extra shifts) to work across local aspects consistent and current’. This should be considered, espe-

of implementation. However, this was rarely accepted as cially in regard to planning for sustainability, as imple-

sites found it difficult to spare someone the time, and mentation is less likely to be successful in organisations

local work was often done by a clinician around their with high staff turnover [27].

normal work role. Sites that were able to make use of

this funding for dedicated time towards local implemen- Scale reliability

tation of the project benefitted greatly. Q26 explored These data demonstrate that the TDF is a useful tool for

local networks and highlights that better collaboration designing specific questions to evaluate implementation

and involvement across departments help implementa- behaviours. Our instrument was shown to be reliable in so

tion efforts. Similar points have been discussed under far as the items for each scale are measuring similar and

Social/professional role and identity. To highlight these related constructs. This provides support to the items and

points further, Q26 comments include, ‘Would not have scales proposed by Huijg et al. [17], which formed the

started without team liaising with and convincing local basis for our questionnaire. All scales demonstrated good

cardiologist to use it’ and ‘ACRE mostly adapted unilat- reliability, and are promising for use in future research,

erally by ED with some cardiology agreement’. such as further investigating the concurrent and predictive

validity and reliability of the questionnaire in practice [17].

Social influences We tailored the instrument to suit our purposes and

The Social influences scale shows the lowest mean (with purposefully excluded one domain (Emotion) from the

Environmental context and resources) and the most overall questionnaire based on relevance. The rationale

variability, but responses overall were still very positive. for leaving out scales is specific to the nature of the

Interestingly, this was the only scale to show a signifi- programme and therefore needs to be judged on a case-

cant difference between hospitals by implementation by-case basis. The TDF is a useful framework for evalu-

time, suggesting that wider support for the ACRE pro- ation but is very broad and encompassing and therefore

ject improved over time as the pathway became embed- it is likely to require tailoring or shaping to the local im-

ded into routine practice. This aligns with Rogers plementation context. We have demonstrated how this

‘diffusion of innovations’ model in which there is some can be successfully achieved.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 9 of 11

Limitations Finally, whilst we report the ACRE project as being

This study had a few limitations. The questionnaire was widely and successfully implemented across 19 sites,

not pre-tested to establish feasibility before using it for there were different levels of ‘success’ and engagement

the principal data collection phase. This was primarily between sites, for example, the time and effort taken to

for logistical reasons including time constraints and a implement into practice, and use and uptake of the

lack of a relevant sample group to enable such testing to ACRE pathway in practice varied. Further examination

take place. With a larger implementation project, a small between sites that varied in ‘success’ by these measures

scale pre-test is advisable. We acknowledge that the did not reveal any major variation in responses. How-

questionnaire results may have been affected by several ever, rather than a fault of the TDF or questionnaire to

factors, influencing respondent bias. First, it is likely that differentiate this, we were limited by low (or nil)

the overwhelmingly positive responses to the survey responses from several sites that we felt were not as

questions were at least partly due to the stakeholders ‘successful’ in implementation. Similarly, low numbers of

most engaged with and positive about the ACRE project responses in several categories for statistical compari-

being the ones who completed the survey. Furthermore, sons, such as hospital type and size, limit generalizability

social desirability bias may have influenced results. Each of the findings.

clinician that completed the survey has had prior com-

munication and interaction with the ACRE project team

and therefore may have been more likely to give us posi- Conclusions

tive feedback. However, it is our experience that medical The TDF was used to guide questionnaire development

specialists and clinicians are not averse to reporting their to evaluate the factors driving the highly successful

true feelings on the nature of an intervention that dir- implementation of the ACRE project in multiple sites

ectly affects them. Moreover, the surveys were anonym- across Queensland with varying characteristics. Stake-

ous and any reputation effects or concern for negative holder survey results were overwhelmingly positive, with

impact would be largely mitigated by this. Additionally, high mean responses across all scales, demonstrating

accuracy of some responses may have been influenced that the implementation strategy was effective. However,

by recall bias, as some respondents were completing the whilst the domains did not appear very discriminatory

survey more than 12 months after the initial implemen- and a lack of variance in the responses hampered us

tation period, despite regular and ongoing (e.g. at least from concluding which factors were really driving

once monthly) email correspondence from the project success, they did match positive outcomes with posi-

team. The option of a ‘Don’t know/NA’ response for tive responses and so could therefore be used as a

each survey question was designed to limit this bias. starting point for assessing future projects of a similar

High mean responses across all domains made it dif- nature.

ficult to gauge their relative importance to implemen- The TDF offers a useful framework to conceptualise

tation outcomes and limited the ability to explore if and evaluate factors impacting on implementation

there are any important interactions between the success. However, its broad scope makes it necessary

domains. Interviews, follow-up questions or a different to tailor and adapt it to the specific purpose of ques-

survey design may have helped answer these questions; tion at hand. This had advantages and disadvantages.

however, questionnaires that were simple to complete It places a large burden on researchers, often lacking

were used as they enabled us to sample a larger in psychometric expertise, to develop their own ques-

number of stakeholders. Additionally, despite broadly tions. Future research could focus on the rigorous

encompassing factors using the TDF, the questions systematic development of scales or instruments to

used were limited by our selection of determinants and assess implementation success both pre- and post-

therefore may not have captured all relevant factors implementation. This may help to determine which

influencing implementation. Other factors, beyond the factors actually influence success and would benefit

scope of the TDF questions, would also have impacted from action, as well as help specify any relationships

on the success of the project. For example, macro between the domains. It would also enable the com-

organisational factors such as readiness to adopt (or- parison of findings across studies, which is difficult to

ganisational culture) and political pressures on hospi- achieve without standardised scales.

tals to reduce waiting times in EDs are systemic factors

linked to implementation success. However, it is diffi- Additional files

cult to assess their real impact at the local level, and

we therefore focused our efforts on examining local Additional file 1: ACRE project implementation evaluation

questionnaire. (DOC 105 kb)

stakeholders’ responses in regard to their own local

Additional file 2: Collated survey responses. (XLSX 22 kb)

implementation.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 10 of 11

Abbreviations References

ACRE: Accelerated Chest pain Risk Evaluation; ADAPT: 2-Hour Accelerated 1. Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care

Diagnostic Protocol to Assess Patients With Chest Pain Symptoms Using improvement. Yearbook of Medical Informatics. 2000. p. 65–70.

Contemporary Troponins as the Only Biomarker; ADP: Accelerated diagnostic 2. Grant J, Green L, Mason B. Basic research and health: a reassessment of the

protocol; EBP: Evidence-based practice; ED: Emergency departments; scientific basis for the support of biomedical science. Res Eval. 2003;12(3):

TDF: Theoretical Domains Framework 217–24. doi:10.3152/147154403781776618.

3. Mitton C, Adair CE, McKenzie E, Patten SB, Perry BW. Knowledge transfer

Acknowledgements and exchange: review and synthesis of the literature. Milbank Q. 2007;85(4):

We would like to thank participants for their survey responses, as well as all 729–68. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00506.x.

the clinicians, administrative staff, and executives across the multiple sites 4. Bornmann L. Measuring the societal impact of research: research is less and

involved in implementing the ACRE project and ADAPT-ADP into practice. less assessed on scientific impact alone—we should aim to quantify the

All of the authors except KP were employed part-time on the ACRE project increasingly important contributions of science to society. EMBO Rep. 2012;

from funding from the Queensland Department of Health, Clinical Redesign 13(8):673–6. doi:10.1038/embor.2012.99.

and Innovation Board (CRIB), Health Innovation Fund (HIF). Project guidance 5. Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks.

and support was provided by the Healthcare Improvement Unit (HIU), Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0.

formerly known as the Clinical Access and Redesign Unit (CARU). KP did not 6. Martin BR. The research excellence framework and the 'impact agenda': are

receive any funding for her work on the manuscript and study design and we creating a Frankenstein monster? Res Eval. 2011;20(3):247–54. doi:10.

was introduced to the ACRE project team from the Australian Centre for 3152/095820211X13118583635693.

Health Services Innovation (AusHSI). The views expressed in this paper are 7. Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An

those of the authors and not necessarily the organisations above. introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol.

2015;3:32. doi:10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9.

Funding 8. Eccles MP, Mittman BS. Welcome to implementation science. Implement

The ACRE project was funded by the Health Innovation Fund, Clinical Sci. 2006;1:1. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

Redesign and Innovation Board, Queensland Department of Health. The 9. Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation. Implementation Grant

Health Innovation Fund had no role in data collection or reporting, or in Funding Policy, August 2016, http://www.aushsi.org.au/wp-content/

writing of this manuscript. uploads/2016/08/AusHSI-Implementation-Grant-Funding-Policy-V3-2016.pdf.

Accessed 19 Sept 2016

Availability of data and materials 10. Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research.

article and its additional files. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):37.

11. Francis JJ, O’Connor D, Curran J. Theories of behaviour change

synthesised into a set of theoretical groupings: introducing a thematic

Authors’ contributions

series on the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):

WS led the development of this manuscript. KP undertook analysis and

1–9. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-35.

reporting of the data and results, as well as substantial input into

12. Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A, et al.

questionnaire development, and manuscript review and editing. LC, WP, SA,

Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based

and TM provided substantial input into the study and design, and

practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi:

manuscript review and editing. All authors reviewed and accepted the final

10.1136/qshc.2004.011155.

version of the manuscript.

13. Than M, Cullen L, Aldous S, Parsonage WA, Reid CM, Greenslade J, et al. 2-

hour accelerated diagnostic protocol to assess patients with chest pain

Authors’ information symptoms using contemporary troponins as the only biomarker: the ADAPT

LC and WP are the clinical leads of the ACRE project and specialists in trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(23):2091–8. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.035.

Emergency Medicine and Cardiology, respectively. WS, SA, and TM are 14. George T, Ashover S, Cullen L, Larsen P, Gibson J, Bilesky J, et al.

project officers of the ACRE project. KP is a psychologist associated with the Introduction of an accelerated diagnostic protocol in the assessment of

Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation (AusHSI). emergency department patients with possible acute coronary syndrome:

the Nambour Short Low-Intermediate Chest pain project. Emerg Med

Competing interests Australas. 2013;25(4):340–4. doi:10.1111/1742-6723.12091.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. 15. Parsonage W, Ashover S, Milburn T, Skoien W, Cullen L. Translation of the ADAPT

accelerated diagnostic protocol into clinical practice: impact on hospital length of

Consent for publication stay and admission rates for possible cardiac chest pain. Rome: Accepted for

Not applicable. presentation at: European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress; 2016.

16. Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J, Angelini K, Capewell S, Nicholl J. The

Ethics approval and consent to participate health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart. 2005;91(2):229–30.

The Gold Coast Health Service District Human Research Ethics Committee doi:10.1136/hrt.2003.027599.

deemed the ACRE project exempt from review as it was categorised as a 17. Huijg J, Gebhardt W, Crone M, Dusseldorp E, Presseau J. Discriminant

Quality Activity and not recognised as research (HREC/13/QGC/142). content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in

Questionnaires included the following statement regarding respondents implementation research. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):11.

consent: ‘If you agree to take part, please complete and return the 18. Curran J, Brehaut J, Patey A, Osmond M, Stiell I, Grimshaw J. Understanding

questionnaire. The return of the completed questionnaire will be taken as the Canadian adult CT head rule trial: use of the theoretical domains

agreement for your information to be used in this project. Reporting or framework for process evaluation. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):25.

publishing of results and information you submit will not be identifiable in 19. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Hospital-hospital peer group,

any way’. modified code N, http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/

584666. Accessed 30 Oct 2015

Author details 20. McGrath KM, Bennett DM, Ben-Tovim DI, Boyages SC, Lyons NJ, O'Connell

1

Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Butterfield St & Bowen Bridge Rd, TJ. Implementing and sustaining transformational change in health care:

Herston, QLD 4006, Australia. 2Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, lessons learnt about clinical process redesign. MJA. 2008;188(6):S32–5.

Queensland University of Technology, 60 Musk Avenue, Kelvin Grove, QLD, 21. Ajzen I. Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Milton Keynes: Open Univ.

Australia. Press; 1988.

22. Ajzen I. Theories of cognitive self-regulation: the theory of planned

Received: 15 May 2016 Accepted: 3 October 2016 behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Skoien et al. Implementation Science (2016) 11:136 Page 11 of 11

23. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC.

Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice:

a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science.

Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

24. Kirsh SR, Lawrence RH, Aron DC. Tailoring an intervention to the context

and system redesign related to the intervention: a case study of

implementing shared medical appointments for diabetes. Implement Sci.

2008;3:34. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-3-34.

25. Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. New York; London: Free Press; 2003.

26. Walston SL, Kimberly JR, Burns LR. Institutional and economic influences on

the adoption and extensiveness of managerial innovation in hospitals: the

case of reengineering. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58(2):194–228.

doi:10.1177/107755870105800203.

27. Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. Disrupted routines: team

learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Adm Sci Q.

2001;46(4):685–716.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and we will help you at every step:

• We accept pre-submission inquiries

• Our selector tool helps you to find the most relevant journal

• We provide round the clock customer support

• Convenient online submission

• Thorough peer review

• Inclusion in PubMed and all major indexing services

• Maximum visibility for your research

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions

Springer Nature journal content, brought to you courtesy of Springer Nature Customer Service Center GmbH (“Springer Nature”).

Springer Nature supports a reasonable amount of sharing of research papers by authors, subscribers and authorised users (“Users”), for small-

scale personal, non-commercial use provided that all copyright, trade and service marks and other proprietary notices are maintained. By

accessing, sharing, receiving or otherwise using the Springer Nature journal content you agree to these terms of use (“Terms”). For these

purposes, Springer Nature considers academic use (by researchers and students) to be non-commercial.

These Terms are supplementary and will apply in addition to any applicable website terms and conditions, a relevant site licence or a personal

subscription. These Terms will prevail over any conflict or ambiguity with regards to the relevant terms, a site licence or a personal subscription

(to the extent of the conflict or ambiguity only). For Creative Commons-licensed articles, the terms of the Creative Commons license used will

apply.

We collect and use personal data to provide access to the Springer Nature journal content. We may also use these personal data internally within

ResearchGate and Springer Nature and as agreed share it, in an anonymised way, for purposes of tracking, analysis and reporting. We will not

otherwise disclose your personal data outside the ResearchGate or the Springer Nature group of companies unless we have your permission as

detailed in the Privacy Policy.

While Users may use the Springer Nature journal content for small scale, personal non-commercial use, it is important to note that Users may

not:

1. use such content for the purpose of providing other users with access on a regular or large scale basis or as a means to circumvent access

control;

2. use such content where to do so would be considered a criminal or statutory offence in any jurisdiction, or gives rise to civil liability, or is

otherwise unlawful;

3. falsely or misleadingly imply or suggest endorsement, approval , sponsorship, or association unless explicitly agreed to by Springer Nature in

writing;

4. use bots or other automated methods to access the content or redirect messages

5. override any security feature or exclusionary protocol; or

6. share the content in order to create substitute for Springer Nature products or services or a systematic database of Springer Nature journal

content.

In line with the restriction against commercial use, Springer Nature does not permit the creation of a product or service that creates revenue,

royalties, rent or income from our content or its inclusion as part of a paid for service or for other commercial gain. Springer Nature journal

content cannot be used for inter-library loans and librarians may not upload Springer Nature journal content on a large scale into their, or any

other, institutional repository.

These terms of use are reviewed regularly and may be amended at any time. Springer Nature is not obligated to publish any information or

content on this website and may remove it or features or functionality at our sole discretion, at any time with or without notice. Springer Nature

may revoke this licence to you at any time and remove access to any copies of the Springer Nature journal content which have been saved.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, Springer Nature makes no warranties, representations or guarantees to Users, either express or implied

with respect to the Springer nature journal content and all parties disclaim and waive any implied warranties or warranties imposed by law,

including merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

Please note that these rights do not automatically extend to content, data or other material published by Springer Nature that may be licensed

from third parties.

If you would like to use or distribute our Springer Nature journal content to a wider audience or on a regular basis or in any other manner not

expressly permitted by these Terms, please contact Springer Nature at

onlineservice@springernature.com

You might also like

- Test Bank For Microbiology For The Healthcare Professional 2nd Edition Karin C Vanmeter Robert J HubertDocument21 pagesTest Bank For Microbiology For The Healthcare Professional 2nd Edition Karin C Vanmeter Robert J HubertTammyEricksonfitq98% (46)

- EQ-i - Emotional Quotient Inventory - The EQ-i 2.0 PortalDocument2 pagesEQ-i - Emotional Quotient Inventory - The EQ-i 2.0 Portalrosabel0420% (5)

- 2023mar15 Hippocratic Medicine Pi HRGDocument155 pages2023mar15 Hippocratic Medicine Pi HRGCNBC.comNo ratings yet

- Hartland Memorial Hospital Case StudyDocument26 pagesHartland Memorial Hospital Case StudyZubeen ShahNo ratings yet

- TDF On Primary CareDocument16 pagesTDF On Primary CareLammeessaa Assefa AyyaanaNo ratings yet

- The Dynamic Sustainability Framework: Addressing The Paradox of Sustainment Amid Ongoing ChangeDocument11 pagesThe Dynamic Sustainability Framework: Addressing The Paradox of Sustainment Amid Ongoing ChangeATHINA DARLYNE PEREZ FIGUEROANo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 115Document9 pages2020 Article 115Alessandra BendoNo ratings yet

- Effective Strategies For Scaling Up Evidence-Based PDFDocument13 pagesEffective Strategies For Scaling Up Evidence-Based PDFAbraham LebezaNo ratings yet

- Implementation Fidelity of A Nurse-Led Falls Prevention Program in Acute Hospitals During The 6-PACK TrialDocument10 pagesImplementation Fidelity of A Nurse-Led Falls Prevention Program in Acute Hospitals During The 6-PACK TrialDedes SahpitraNo ratings yet

- Recognising and Responding To In-Hospital Clinical DeteriorationDocument39 pagesRecognising and Responding To In-Hospital Clinical DeteriorationPAULA SORAIA CHENNo ratings yet

- Struggling For A Feasible Tool - The Process of Implementing A Clinical Pathway in Intensive Care: A Grounded Theory StudyDocument15 pagesStruggling For A Feasible Tool - The Process of Implementing A Clinical Pathway in Intensive Care: A Grounded Theory StudyHarumiNo ratings yet

- s12630-017-0846-8Document5 pagess12630-017-0846-8Lukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Barriers To The Implementation of Preconception Care Guidelines As Perceived by General Practitioners: A Qualitative StudyDocument8 pagesBarriers To The Implementation of Preconception Care Guidelines As Perceived by General Practitioners: A Qualitative StudyWondwosen AsegidewNo ratings yet

- Short-And Long-Term Effects of A Quality Improvement Collaborative On Diabetes ManagementDocument10 pagesShort-And Long-Term Effects of A Quality Improvement Collaborative On Diabetes ManagementBhisma SyaputraNo ratings yet

- Powell PDFDocument14 pagesPowell PDFAngellaNo ratings yet

- TDF+ BCWDocument17 pagesTDF+ BCWAlaa AlanaziNo ratings yet

- Changing Practice: Frameworks From Implementation ScienceDocument4 pagesChanging Practice: Frameworks From Implementation ScienceLink079No ratings yet

- Barreras Facilitadores Implementacion LabioDocument9 pagesBarreras Facilitadores Implementacion LabioOpeNo ratings yet

- Implications in Practice and Conclusions - EditedDocument11 pagesImplications in Practice and Conclusions - EditedAtanas WamukoyaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Translation of Research Findings: Debate Open AccessDocument17 pagesKnowledge Translation of Research Findings: Debate Open AccessHANo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 894Document12 pages2019 Article 894Elfina NataliaNo ratings yet

- A Review of Telehealth Service Implementation FrameworksDocument20 pagesA Review of Telehealth Service Implementation FrameworksKartik DograNo ratings yet

- 02 International PDFDocument15 pages02 International PDFjumaidi ratnaNo ratings yet

- Michael Et Al-2013-Journal For Healthcare QualityDocument11 pagesMichael Et Al-2013-Journal For Healthcare QualityjessicaNo ratings yet

- s12961-018-0304-2Document15 pagess12961-018-0304-2LUISA FERNANDA OCHOA VILLEGASNo ratings yet

- MacFarlane 2010 NormalizationDocument11 pagesMacFarlane 2010 NormalizationKarina CancellaNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Assessing The Quality of Clinical Practice Guidelines in Paediatrics and Neonatology: A Mixed-Method StudyDocument12 pagesCriteria For Assessing The Quality of Clinical Practice Guidelines in Paediatrics and Neonatology: A Mixed-Method StudyGreg RsNo ratings yet

- Basic PDFDocument2 pagesBasic PDFAshilla ShafaNo ratings yet

- Reporting Guidelines For Implementation and Operational ResearchDocument7 pagesReporting Guidelines For Implementation and Operational ResearchDanNo ratings yet

- 11 9 15 130 Brownson WedgwoodDocument47 pages11 9 15 130 Brownson WedgwoodLEO MWINNo ratings yet

- Periop Outcomes in PedsDocument9 pagesPeriop Outcomes in Pedsrtaneja92No ratings yet

- 232 FullDocument14 pages232 FullCarlos OliveiraNo ratings yet

- 556-Appropriateness of Clinical Decision Support - Final White Paper-Wei WuDocument15 pages556-Appropriateness of Clinical Decision Support - Final White Paper-Wei Wuapi-398506399No ratings yet

- Jurnal Triad of Concern 2 PDFDocument10 pagesJurnal Triad of Concern 2 PDFKharina AreeistyNo ratings yet

- 08 Research UtilizationDocument9 pages08 Research UtilizationGurkirat TiwanaNo ratings yet

- Implementation of A Multidisciplinary Guideline For Low Back Pain Process Evaluation Among Health Care ProfessionalsDocument12 pagesImplementation of A Multidisciplinary Guideline For Low Back Pain Process Evaluation Among Health Care Professionalscallisto69No ratings yet

- Lean Management in The Emergency Department: June 2018Document14 pagesLean Management in The Emergency Department: June 2018fajr muzzammilNo ratings yet

- Editorial: Evidence-Based Decision Making in Occupational HealthDocument2 pagesEditorial: Evidence-Based Decision Making in Occupational HealthNutanNo ratings yet

- Normalisation Process Theory A Framework For Developing, Evaluating and Implementing Complex InterventionsDocument12 pagesNormalisation Process Theory A Framework For Developing, Evaluating and Implementing Complex InterventionsTran Ngoc TienNo ratings yet

- Implementation Strategies and Outcomes For Occupational Therapy in Adult Stroke Rehabilitation: A Scoping ReviewDocument26 pagesImplementation Strategies and Outcomes For Occupational Therapy in Adult Stroke Rehabilitation: A Scoping ReviewNataliaNo ratings yet

- Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology ProjectDocument41 pagesWriting The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Projectrcaba100% (1)

- 2016 Slade CERTDocument30 pages2016 Slade CERTdamicarbo_297070015No ratings yet

- Evaluation of A Multidisciplinary Lipid Clinic ToDocument11 pagesEvaluation of A Multidisciplinary Lipid Clinic ToBRYAN YESKEL MBAUBEDARINo ratings yet

- Integrating New Practices: A Qualitative Study of How Hospital Innovations Become RoutineDocument12 pagesIntegrating New Practices: A Qualitative Study of How Hospital Innovations Become RoutineMas MujionoNo ratings yet

- 2021 Article 861Document15 pages2021 Article 861NataliaNo ratings yet

- s13063 019 3444 yDocument12 pagess13063 019 3444 yAlessandra BendoNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practice Project ProposalDocument7 pagesEvidence-Based Practice Project Proposalwamburamuturi001No ratings yet

- QI Student Proposal Handoffs PDFDocument6 pagesQI Student Proposal Handoffs PDFDxtr MedinaNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Interventions To Improve Laboratory Requesting Patterns Among Primary Care Physicians: A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesThe Effectiveness of Interventions To Improve Laboratory Requesting Patterns Among Primary Care Physicians: A Systematic ReviewGNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal On Improving QualityDocument4 pagesProject Proposal On Improving Qualityzakuan79100% (2)

- Implementation of A Spontantaneous Breathing Trial Protocol Friendly)Document16 pagesImplementation of A Spontantaneous Breathing Trial Protocol Friendly)Reema KhalafNo ratings yet

- Application of Lean OrbitDocument26 pagesApplication of Lean OrbitHamada H. ShaatNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PX Safety PDFDocument7 pagesJurnal PX Safety PDFChairunnisa Permata SariNo ratings yet

- Enhancedrecoveryafter Surgery: Implementation Strategies, Barriers and FacilitatorsDocument10 pagesEnhancedrecoveryafter Surgery: Implementation Strategies, Barriers and Facilitatorsasm obginNo ratings yet

- Developing A Theory-Based Instrument To Assess The Impact of Continuing Professional Development Activities On Clinical Practice: A Study ProtocolDocument6 pagesDeveloping A Theory-Based Instrument To Assess The Impact of Continuing Professional Development Activities On Clinical Practice: A Study ProtocolSjktraub PahangNo ratings yet

- Fasilita RefDocument10 pagesFasilita RefsukrangNo ratings yet

- UsingImplementation 032513compDocument11 pagesUsingImplementation 032513compJames LindonNo ratings yet

- Curran, 2012 - Effectiveness-Implementation Hybrid DesignsDocument10 pagesCurran, 2012 - Effectiveness-Implementation Hybrid DesignsThuane SalesNo ratings yet

- An To Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (Proms) in PhysiotherapyDocument7 pagesAn To Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (Proms) in PhysiotherapyAline VidalNo ratings yet

- Narrative Review of Models and Success Factors For Scaling Up Public Health InterventionsDocument11 pagesNarrative Review of Models and Success Factors For Scaling Up Public Health InterventionsRamani SwarnaNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article 1603Document12 pages2016 Article 1603Nino AlicNo ratings yet

- Intensive & Critical Care Nursing: Ziad Alostaz, Louise Rose, Sangeeta Mehta, Linda Johnston, Craig DaleDocument11 pagesIntensive & Critical Care Nursing: Ziad Alostaz, Louise Rose, Sangeeta Mehta, Linda Johnston, Craig DalecindyNo ratings yet

- Advanced Practice and Leadership in Radiology NursingFrom EverandAdvanced Practice and Leadership in Radiology NursingKathleen A. GrossNo ratings yet

- Modern Guide To Lead Qualification - ClearbitDocument112 pagesModern Guide To Lead Qualification - ClearbitLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Priyanka Rai Master ThesisDocument65 pagesPriyanka Rai Master ThesisLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- A Breakdown of 5 Lead Qualification Frameworks - CopperDocument10 pagesA Breakdown of 5 Lead Qualification Frameworks - CopperLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Lead Qualification Maturity Benchmarks WorksheetsDocument8 pagesLead Qualification Maturity Benchmarks WorksheetsLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- How To Choose A Lead Qualification Framework? 7 Examples To Pick FromDocument16 pagesHow To Choose A Lead Qualification Framework? 7 Examples To Pick FromLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Marketing Intelligence & Planning: Article InformationDocument19 pagesMarketing Intelligence & Planning: Article InformationLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 18 02781 v2Document11 pagesIjerph 18 02781 v2Lukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Area Per Player in Small Sided Games To Replicate The Relative External Load Estimated Physiological Match Demands in Elite Soccer PlayersDocument1 pageArea Per Player in Small Sided Games To Replicate The Relative External Load Estimated Physiological Match Demands in Elite Soccer PlayersLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Small-Sided & Conditioned Games (SSCG) in Football: Implications For Training DesignDocument1 pageA Practical Guide To Small-Sided & Conditioned Games (SSCG) in Football: Implications For Training DesignLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Activity and Injury: Lessons Learned From The Acute:Chronic Workload RatioDocument12 pagesAnalyzing Activity and Injury: Lessons Learned From The Acute:Chronic Workload RatioLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Sports: Training Management of The Elite Adolescent Soccer Player Throughout MaturationDocument21 pagesSports: Training Management of The Elite Adolescent Soccer Player Throughout MaturationLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- The Coaches' Efficacy Expectations of Youth Soccer Players With Different Maturity Status and Physical PerformanceDocument10 pagesThe Coaches' Efficacy Expectations of Youth Soccer Players With Different Maturity Status and Physical PerformanceLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Integrated Performance Support: Facilitating Effective and Collaborative Performance TeamsDocument3 pagesIntegrated Performance Support: Facilitating Effective and Collaborative Performance TeamsLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Rating of Perceived Effort: Methodological Concerns and Future DirectionsDocument9 pagesRating of Perceived Effort: Methodological Concerns and Future DirectionsLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Intuitive Eating Journal: The Hunger-Fullness Scale in BriefDocument3 pagesIntuitive Eating Journal: The Hunger-Fullness Scale in BriefCássia PohlNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 Importance of Quantitative Research Across Different FieldsDocument20 pagesLesson 2 Importance of Quantitative Research Across Different Fieldsjestoni manipolNo ratings yet

- Module-6: Managing Health and SafetyDocument35 pagesModule-6: Managing Health and Safetyshubham shahNo ratings yet

- Rethink Your Drink PDFDocument3 pagesRethink Your Drink PDFSandy HernandezNo ratings yet

- Farmington High School Covid19 ClosureDocument1 pageFarmington High School Covid19 ClosureAlyssa RobertsNo ratings yet

- Summary of Burn Rate: Launching A Startup and Losing My MindDocument38 pagesSummary of Burn Rate: Launching A Startup and Losing My MindKevin AdekolaNo ratings yet

- MCQ Dental.Document5 pagesMCQ Dental.anuj sharmaNo ratings yet

- SDS - Hydraulic 32Document9 pagesSDS - Hydraulic 32Zaw Htet WinNo ratings yet

- đề tnDocument14 pagesđề tnLưu Lê Minh HạNo ratings yet

- BS Psych 1 Yb3Document2 pagesBS Psych 1 Yb3sumi raiNo ratings yet

- Ikigai Worksheet: Passion MissionDocument1 pageIkigai Worksheet: Passion Missiontelpastor100% (1)