Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BookReview Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons Conflict Redux (1)

BookReview Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons Conflict Redux (1)

Uploaded by

Devi SinghCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BookReview Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons Conflict Redux (1)

BookReview Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons Conflict Redux (1)

Uploaded by

Devi SinghCopyright:

Available Formats

scholar warrior

Book Reviews

Pakistan’s Tactical Nuclear Weapons Conflict Redux

Edited by Gurmeet Kanwal & Monika Chansoria

KW Publishers Pvt Ltd, 2013, 232 pages, Rs. 740

Pakistan’s nuclear programme is India-centric with a view to marginalise India’s

conventional edge. With a first use nuclear weapon policy, Pakistan would

seek to lower the threshold for usage of these munitions to coerce India not

to respond militarily when subjected to an asymmetric jihadi strike. Pakistan

has undertaken dastardly terrorist attacks with Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI)

trained militants against civilian targets in India and has not been confronted

with a military response from India. This has led to a strategic brinkmanship.

Pakistan keeps playing the nuclear card with dexterity, compelling India to

constantly find an answer to the nuclear dilemma. The development of the

60-km Tactical Nuclear Weapon (TNW) Nasr has added a new dimension. This

book, edited by Gurmeet Kanwal and Monika Chansoria has many renowned

contributors, who address many issues regarding this weapon. Apart from the

editors, there are contributions by Bharat Karnad, Vijay Shankar Shankar, Kapil

Kak, Arun Sahgal, Sasikumar, Nagappa, Shalini Chawla, Rajesh Rajagopalan and

Manpreet Sethi.

The introductory chapter clearly states that the nuclear weapons of Pakistan

are for deterrence, and providing parity with India in the politico-strategic realm.

The actual possibility of use of tactical and strategic nuclear weapons is zero.

The book quotes senior Pakistani officers who have categorically stated that the

Indian response to Pakistan’s first use would be a total holocaust. The chapter

188 ä autumn 2014 ä scholar warrior

scholar warrior

points out that in late 2010, with 90 TNWs, it was difficult for Pakistan to stop an

Indian Armoured Division moving dispersed on a 30 km frontage. There would

be a minimum inescapable requirement of 436 TNWs to stop an armoured

division. The reported accelerated production of plutonium from three military

dedicated reactors in Khushab and a fourth under construction, would result

in an inventory of 200 warheads by 2020. To further compound the existing

problem, the issue of miniaturising the warhead to fit into the Nasr missile with

a 30 cm diameter is a complex engineering problem. The chapter also speaks of

grabbing a city close to the border which would present nuclear targets to the

Pakistan Strategic Plans Division to employ nuclear weapons.

The book lucidly brings out the help provided by China in developing nuclear

weapons and delivery systems for Pakistan. This was done despite China signing

the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1982. China supplied inputs

regarding enriched uranium and a 25 kiloton bomb in 1983, and the production

facility for the M-11 missiles. Further, China sold 5,000 ring magnets to Pakistan

to be used in high speed centrifuges. With regard to TNW, the book correctly

establishes that circumstantial evidence points to covert assistance given by

China to Pakistan.

The paper on Pakistani doctrinal thinking with regard to nuclear weapons,

interestingly states that if the need arises, Pakistan could be irrational in using

nuclear weapons, even involving the destruction of its own people if pushed

beyond a limit. Further, the paper describes the implications of thresholds

pertaining to preemptive response, early response, delayed response and

accumulated response. Pakistan is likely to resort to the use of TNWs as

perceived low cost strategic weapons under conditions where it perceives a

major operational defeat such as unacceptable loss of territory threatening high

value targets, serious degradation of military potential and attacks on critical

infrastructure important for its war-waging effort. The control of TNWs remains

unstated but given their limited range, they would have to be placed under the

theatre commanders for effective employment. The response by India as given in

the paper is a graduated retaliation likely to cause extensive damage to Pakistan.

Further, in the Pakistani attempts to convey threshold ambiguity, the nuclear trip

wires are not seen as uniform. These appear to be much shorter and tighter in

the Punjabi heartland, relatively more stretched in Sindh and loose in Pakistan

Occupied Kashmir (POK). Thus, the Pakistani response would be different,

depending on the sector addressed. TNWs are part of the Pakistani nuclear

doctrine and India has to, therefore, calibrate its response to this aspect.

scholar warrior ä autumn 2014 ä 189

scholar warrior

The paper on command and control in the context of TNWs highlights the

set-up needed to handle this threat from Pakistan. The draft Indian Nuclear

Doctrine prepared by the National Security Advisory Board (NSAB) of the National

Security Council has stated that the authority to release nuclear weapons for

use rests with the Prime Minister of India. On January 04, 2003, the Cabinet

Committee on Security (CCS) adopted and made public key elements of India’s

nuclear doctrine as also the command and control structure. The Prime Minister

and the CCS now comprise India’s Nuclear Command Authority (NCA). In the

NCA, the Political Council headed by the Prime Minister is the sole authority for

ordering a nuclear strike. The Political Council is advised by an Executive Council

headed by the National Security Adviser (NSA). The Executive Council executes

decisions through the Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC) and the

Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) Strategic Forces Command. As regards Pakistan,

the Pakistan Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) exercises control over the nuclear

weapons. They have a Strategic Plans Division (SPD) and each of the Services has

a Strategic Forces Command (SFC). Though the nuclear weapons are stored by

the SPD, in the case of TNWs, these would have to be with the SFC of the Army,

thereby, leading to fully mated nuclear weapons being stored with the theatre

commanders, causing decentralised deployment of this critical asset. This could

lead to unauthorised or accidental launches for which India must be prepared.

The details of the imageries obtained indicate that Nasr is a 300 mm missile

mounted on a Chinese A 100 Transport Erector Launcher (TEL).The Pakistani

TNWs have been developed to pour cold water on India’s cold start doctrine and

as, per the book, India should respond with its second strike capability. The book

could have brought out counter-measures like the Iron Dome to the Nasr which

degrades its capability, if successfully intercepted.

The book is extremely well researched and compiled. It is a must read for

officials in the Ministries of Defence and External Affairs, strategic analysts and

all serving and retired officers of the armed forces.

Review by Maj Gen PK Chakravorty. The reviewer was an adviser to BrahMos Aerospace.

190 ä autumn 2014 ä scholar warrior

scholar warrior

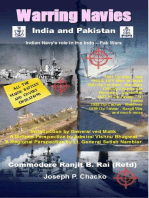

Warring Navies-India and Pakistan

Commodore Ranjit B Rai (Retd) and Joseph P Chacko

India Publications Company, 2014, 264 pages, Rs 399

God and a Soldier people adore

In time of War, not before;

And when war is over and all things are righted

God is neglected and an old Soldier slighted.

Crippling of the NRP Afonso de Albuquerque on December 18, 1961, by the INS

Betwa and Beas, the raid on Dwarka (site of the Somnath temple) on September

07, 1965, by the Pakistani task force, the reasons for the Navy’s ‘Sweet Fanny

Adams’ in 1962 and 1965, the mystery around the sinking of the PNS Ghazi in

December 1971, the immense unrecognised contribution of the Mukti Bahini at

sea, the missile boat attacks on Karachi, the exploits of the INS Vikrant in the Bay

of Bengal, the loss of the INS Khukri on December 09, 1971, the story of forgotten

and unsung heroes Roy Chou and Aku Roy, and many such other indelible

watermarks left by brave sailors on the operational history of the Indian Navy

have found their way in the book titled Warring Navies – India and Pakistan. The

book not only attempts to speak for the naval fraternity of India and Pakistan

but goes beyond to include fascinating and comprehensive details of Operation

Lal Dora in Mauritius (1983), Operation Flowers are Blooming in Seychelles

(1987), Operation Pawan in Sri Lanka, Operation Cactus in Maldives (1988)and

Operation Talwar during Kargil.

The Warring Navies is indeed a welcome addition to the limited body of

literature which exists on operations of the Indian Navy. This book is the second

one on the subject by Commodore Ranjit Rai and is co-authored with Joseph P

Chacko. The Warring Navies provides a ringside view of operations conducted by

the Indian Navy post-independence. The authors provide a lucid commentary of

all major military operations, juxtaposed with contemporary geo-politics, which

makes a very interesting and absorbing read. The authors have also made an

endeavour to present the Pakistani view of many important incidents that have

shaped the history of naval operations in the subcontinent. The book includes

an introduction by General Ved Malik, a maritime perspective by Admiral Vishnu

Bhagwat and a regional perspective by Lieutenant General Satish Nambiar.

scholar warrior ä autumn 2014 ä 191

scholar warrior

Commodore Ranjit Bhawani Rai has commanded four naval warships, and

the Naval Academy, served twice as the Director of Operations and later as

Director Intelligence, and has enriched the book with his vast personal experience

and comprehensive research to provide an all-inclusive account of the naval

operations. Commodore Ranjit has also travelled extensively and interacted with

veterans to include Petty Officer Chaman Singh, MVC, in Rewari, Lt Cdr J K Roy

Choudhury, VrC, settled in Lebong, Darjeeling, Commander V P Kapil, VrC in

Delhi, Major Chandrakant, VrC, 1 Guards (4 Rajput) in Delhi and Sajid Zahir from

Dacca, as well as Lieutenant General JFR Jacob. He has also travelled to Pakistan

in 2010 to meet Pakistani naval officers and historians and even met the wives

of some officers who took part in the 1965 and 1971 Wars and has referred to the

books by the Pakistan Book Club. Joseph is a defence journalist, entrepreneur

and the publisher of Frontier India, a portal publishing news and current affairs.

Apart from the details of naval operations and their geo-political context, one

continuous thread that runs along most of the chapters is regarding the dire need

of having a Chief of Defence Staff. It emerges unambiguously that operations in

the past, right from Operation Vijay in 1961, have had a tri-Service participation,

and, hence, involved contentious issues during the planning to include resource

allocation, prioritisation of operational tasks and, ultimately, their execution.

The Prime Minister and the Raksha Mantri, therefore, need to have a single point

of advice and this is possible only if there is a Chief of Defence Staff. The authors

cite many an occasion from the past, purely from the operational perspective, to

emphasise the necessity of the institution.

The book makes an interesting read, particularly in the light of the fact that it

comes from the pen of a man who has seen most of it himself. It is recommended

to be part of all libraries in premier military establishments of the country and

needs to be read by the coming generations, lest they forget the glorious acts, the

valour and the sacrifices of the brave men in whites.

Review by Col Sanjay Sethi. The reviewer is a Senior Fellow, CLAWS.

192 ä autumn 2014 ä scholar warrior

scholar warrior

Fighting to The End:

Pakistan Army’s Way of War

C Christine Fair

Oxford University Press, 2014, 347 pages, Rs 750

Fighting to the End – The Pakistan Army’s Way of War, Dr. C Christine Fair’s

book divided over eleven chapters, is an informative and exhaustive account,

based on painstaking research pursued by her since the early 1990s. The work

draws its data and inferences from the Pakistani military professional writings

spanning almost six (plus) decades. The author admits that the military writing

she has used as base material does not constitute military doctrine. The Pakistani

military (unlike modern Western militaries or, for that matter, India’s) does not

publish its official doctrine. What these writings do show up, believes Fair, is

the Pakistan military’s “strategic culture”. The book primarily delves deep into

“ideological” and “philosophical” dimensions of the Pakistan Army. The reason

for the basis of her Army-centric research, is primarily owing to its all important

role in nationhood. As argued by author; unlike a conventional scenario wherein,

a country has an Army, in Pakistan the Army has a country.

As per the author, the Pakistan Army’s basic discourse has been India-centric,

wherein India is seen as an aggressor, out to destroy Pakistan. Fair argues that

Pakistan is persistently “revisionist” vis-a-vis India, with which it has been

locked in enduring rivalry since 1947-48, ostensibly over Kashmir. As argued by

the author, Pakistan initiated and lost four wars with India, to include loss of

half of its territory in 1971. The philosophy of “asymmetrical war” as practised

by Pakistan has its roots in 1947, rather than in the late 1980s (as is generally

believed) and the same has backfired since 2002. Pakistan’s power differential

with India has been continuously widening and in spite of setbacks, the author

finds a stubborn Pakistan ever more committed to revisionism, with increased

vigour to resist the rise of India.

Conventional wisdom projecting Pakistan as a “security seeking state”

located in a rough neighbourhood, is refuted by the author. She challenges the

notion of reducing the Indo-Pak puzzle to “Kashmir”, and argues that resolution

of the same shall not make Pakistan discard Islamist proxies and its obsession

with the British inherited notion of “strategic depth”. She refutes Pakistan claims

over Kashmir, which is more than being merely a security seeking demand. There

scholar warrior ä autumn 2014 ä 193

scholar warrior

are deep ideological and philosophical differences that Pakistan nurtures against

India, which are unlikely to fade away by simply resolving border disputes,

territorial in nature.

The author has justified the US’ assistance and aid to Pakistan over the

years which were based on the belief that the same would build up Pakistan

conventionally, making it jettison its insecurity and aggressiveness towards

India. She opines that Pakistan is purely an ideological and “greedy state”,

fundamentally dissatisfied with status quo – following revisionism of all kinds, to

enhance its prestige and as a competitive tool to achieve non-security goals. Any

appeasement of the Pakistan Army would only reinforce its revisionist pursuits.

The author has stressed that Pakistan’s sense of insecurity and ideological

differences vis-à-vis India have loomed from partition, based on the two-nation

theory. As perceived by Pakistan, partition has been an unfair and unfinished

agenda thrust upon its people delivering an insecure Pakistan, wherein India

acquired the heartland with all the goodies and positives of the Raj while Pakistan

was made to do with troubled frontiers and an ethnically diverse portion, widely

separated. Fair notes that from the 1950s, Pakistan under Ayub Khan has used

the religious plank to rally the nation and indoctrinate its people against India.

A conscious attempt was made to disseminate the Army’s ideological revisionist

narrative through Pakistani textbooks and to coopt religious-political forces.

As a result, in her words, “both military regimes and civilian governments alike

pursue the army’s revisionist agenda”

The key findings that emerge from the book could be summarised as, firstly,

the Army is the custodian of Pakistan’s ideology and geography. Secondly, India

is civilisationally ‘Hindu’ opposed to Pakistan’s ideological foundations based on

the two-nation theory. Thirdly, the Pakistan Army must resist India’s rise and for

that, the primary tool would be “jihad under the expanding nuclear umbrella”.

The author highlights that Pakistan’s stubbornness to pursue the hard line, in

spite of setbacks, is mainly due to its unique concept of ‘victory’ and ‘defeat’. As

per the prevalent thought in Pakistan, in confrontations of various hues with

India, as long as the Pakistanis survive and preserve the ability to strike back,

they are not considered defeated. And that is how, even the 1971 War is taken as

a victory in Pakistan.

In her attempt to draw out a prognosis for the future, the author remarks that

in its revisionist quest, the Pakistan Army will continue to take significant risks,

rather than do nothing. She has flagged a few aspects that could stand out as

game changers, namely, the transition to democracy, the role of civil society to

194 ä autumn 2014 ä scholar warrior

scholar warrior

give impetus to change, and the economic drivers. All the stated factors presently

are rife with grave challenges. Professor Fair correctly notes that the extrinsic

factors are also unlikely to induce a fundamental change in the strategic culture

of the Pakistan Army.

Many Armies have run their countries, but most of them eventually had to

yield to democratic change and civilian control. The Pakistan Army has been an

exception in this regard and has exercised extraordinary powers, even during

a civilian government. An appreciation of what makes the Pakistan Army tick

should be a high priority for India’s policy-makers and interested agencies and

towards this, Dr. Fair’s solid work has done complete justice.

Review by Col S Ranjan. The reviewer is a Senior Fellow at CLAWS.

scholar warrior ä autumn 2014 ä 195

You might also like

- Nuclear Program of Pakistan International Concerns, Its Safety and SecurityDocument5 pagesNuclear Program of Pakistan International Concerns, Its Safety and Securityinayyat100% (4)

- Pakistan's Battle Eld Nuclear Policy: A Risky Solution To An Exaggerated ThreatDocument34 pagesPakistan's Battle Eld Nuclear Policy: A Risky Solution To An Exaggerated ThreatDorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Nuclear WeaponsDocument3 pagesPakistan Nuclear WeaponsArjun AnandNo ratings yet

- Manpreet Sethi 4Document35 pagesManpreet Sethi 4Dorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and Geo-Political Studies HSS-403: Bahria University (Karachi Campus) Final Assessment Assignment Spring 2020Document10 pagesPakistan and Geo-Political Studies HSS-403: Bahria University (Karachi Campus) Final Assessment Assignment Spring 2020Ali AhmadNo ratings yet

- Indian Tactical Short Range Missiles Fragile Nuclear Doctrine and Doctrinal Crisis Triggers Crisis and Strategic Instability in South AsiaDocument13 pagesIndian Tactical Short Range Missiles Fragile Nuclear Doctrine and Doctrinal Crisis Triggers Crisis and Strategic Instability in South AsiaM I KNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Evolving Doctrine and Emerging Force Posture: Conceptual Nuances and Implied RamificationsDocument15 pagesPakistan's Evolving Doctrine and Emerging Force Posture: Conceptual Nuances and Implied RamificationsDorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- A Mismatch of Nuclear DoctrinesDocument64 pagesA Mismatch of Nuclear DoctrinesSteven RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Polipers 13 1 0153Document12 pagesPolipers 13 1 0153Ali HamzaNo ratings yet

- 11 Low Yield Nuclear Weapons and Scope of Limited War Between India and PakistanDocument13 pages11 Low Yield Nuclear Weapons and Scope of Limited War Between India and PakistanTooba ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Tactical Nuclear Weapons Pakistans Full Spectrum Punitive Offensive Conventional Military Strategy and Punitive Nuclear RetaliationDocument14 pagesTactical Nuclear Weapons Pakistans Full Spectrum Punitive Offensive Conventional Military Strategy and Punitive Nuclear RetaliationDorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- Evolutions of The Nuclear Postures of India and Pakistan and Their Implications For South Asian Crisis DynamicsDocument14 pagesEvolutions of The Nuclear Postures of India and Pakistan and Their Implications For South Asian Crisis DynamicsDorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- Pakistans Nuclear Posture-Security and SurvivabilityDocument19 pagesPakistans Nuclear Posture-Security and SurvivabilityDorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- 1394791164debalina Chatterjee CJ Sumer 2012Document11 pages1394791164debalina Chatterjee CJ Sumer 2012Mein HunNo ratings yet

- Qasim 35 No.2Document24 pagesQasim 35 No.2chichponkli24No ratings yet

- Document Ali AhmadDocument15 pagesDocument Ali AhmadAli AhmadNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Program of PakistanDocument29 pagesNuclear Program of PakistanMemoona AK MughalNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Nuclear Strategy and Deterrence StabilityDocument26 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Strategy and Deterrence StabilityAbdul SattarNo ratings yet

- CRS Report For Congress: Indian and Pakistani Nuclear WeaponsDocument6 pagesCRS Report For Congress: Indian and Pakistani Nuclear Weaponschandu306No ratings yet

- Nuclear Css ForumDocument12 pagesNuclear Css ForumZEESHANNo ratings yet

- Foxtrot to Arihant – The Story of Indian Navy’s Submarine ArmFrom EverandFoxtrot to Arihant – The Story of Indian Navy’s Submarine ArmNo ratings yet

- Jds 5 4 AahmedDocument9 pagesJds 5 4 Aahmedpheonix00No ratings yet

- Geopolitic Hasan Khan Baloch-1Document12 pagesGeopolitic Hasan Khan Baloch-1Ali AhmadNo ratings yet

- Pak India Wars 1965&1971Document210 pagesPak India Wars 1965&1971Surendra TanwarNo ratings yet

- Strategic Relations: The Nuclear Dilemma, (Ibidem-PressDocument6 pagesStrategic Relations: The Nuclear Dilemma, (Ibidem-PressDaim HassanNo ratings yet

- HATF-IX / NASR Pakistan's Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Implications For Indo-Pak DeterrenceDocument50 pagesHATF-IX / NASR Pakistan's Tactical Nuclear Weapons: Implications For Indo-Pak DeterrenceAditi Malhotra100% (2)

- India's Development of Sea-Based NuclearDocument5 pagesIndia's Development of Sea-Based NuclearAgha SufyanNo ratings yet

- 6 Nuclear Learning - SalikDocument16 pages6 Nuclear Learning - SalikKainat FarooqNo ratings yet

- The Indo-Pakistani Nuclear Confrontation: Lessons From The Past, Contingencies For The FutureDocument42 pagesThe Indo-Pakistani Nuclear Confrontation: Lessons From The Past, Contingencies For The FutureMalik MfahadNo ratings yet

- 03 NuclearDocument51 pages03 Nuclearjournalist.tariqNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Nuclear ProgrammeDocument31 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Programmei221534 Muhammad AhmadNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs: 03.08.2015 Pakistan Becomes Member of CERNDocument6 pagesCurrent Affairs: 03.08.2015 Pakistan Becomes Member of CERNRam MahatmiyaNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Weapons Efficacy For Deterrence & Compellence: Post Pulwama AppraisalDocument24 pagesNuclear Weapons Efficacy For Deterrence & Compellence: Post Pulwama AppraisalJason HudsonNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Nuclear Use Doctrine - Carnegie Endowment For International PeaceDocument15 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Use Doctrine - Carnegie Endowment For International PeaceAhsan AbbasNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Power in PakistanDocument5 pagesNuclear Power in PakistanXeenNo ratings yet

- Uncertainities in Nuclear Doctrines of India and PakistanDocument10 pagesUncertainities in Nuclear Doctrines of India and Pakistanhammad HassanNo ratings yet

- 8 Nuclear Learning - ClaryDocument8 pages8 Nuclear Learning - ClaryYumna FatimaNo ratings yet

- Narang PosturingForPeaceDocument42 pagesNarang PosturingForPeaceCarol FairNo ratings yet

- Sgs 07 MianDocument28 pagesSgs 07 MianBee AscenzoNo ratings yet

- On Most Vital ResearchDocument20 pagesOn Most Vital ResearchWaqar Alee TheboNo ratings yet

- Pakistan S Shaheen Missile FamilyDocument11 pagesPakistan S Shaheen Missile FamilyRashid JadoonNo ratings yet

- RSNSinghDocument4 pagesRSNSinghDorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- Clary - Deterrence and Conventional Balance of Forces in South Asia 1Document44 pagesClary - Deterrence and Conventional Balance of Forces in South Asia 1Dorjee SengeNo ratings yet

- EUNPC No-19Document20 pagesEUNPC No-19Mohsin RazaNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Weapons A Source of Peace and Stability Between India and PakistanDocument7 pagesNuclear Weapons A Source of Peace and Stability Between India and Pakistanusama samoNo ratings yet

- 9 Nuclear Learning - MujaddidDocument10 pages9 Nuclear Learning - Mujaddidjohn ericsonnNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons: Paul K. KerrDocument33 pagesPakistan's Nuclear Weapons: Paul K. KerrV XangeNo ratings yet

- RL34248-Pakistan Nuclear WeaponDocument33 pagesRL34248-Pakistan Nuclear WeaponM Usama ZiaNo ratings yet

- Bulletin of The Atomic Scientists 2011 Kristensen 91 9Document10 pagesBulletin of The Atomic Scientists 2011 Kristensen 91 9Anshul ThapliyalNo ratings yet

- 7.21-22.05nalapat MD WrtsDocument4 pages7.21-22.05nalapat MD WrtsAbhijeet JhaNo ratings yet

- South Asia's Unstable Nuclear DecadeDocument12 pagesSouth Asia's Unstable Nuclear DecadePareezay PariNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Bluster or DialogueDocument5 pagesNuclear Bluster or Dialogueh86No ratings yet

- Geopolitic Hasan Khan Baloch-1Document8 pagesGeopolitic Hasan Khan Baloch-1Ali AhmadNo ratings yet

- Pak NavyDocument23 pagesPak NavyZeeshan AmeenNo ratings yet

- Cold StartDocument2 pagesCold StartMarium FatimaNo ratings yet

- 6-Nuclear Program of PakistanDocument12 pages6-Nuclear Program of PakistanDanish KhadimNo ratings yet

- Shalini ChawlaDocument26 pagesShalini Chawlakashiram30475No ratings yet

- Pakistan Is A Nuclear PowerDocument8 pagesPakistan Is A Nuclear Powerahmad tayyabNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Doctrines of India and PakistanDocument25 pagesNuclear Doctrines of India and PakistanfarooqwarraichNo ratings yet

- Delhi Public School, Bathinda Assignment - Class Vii (S.S.T) Ch-3 (History)Document2 pagesDelhi Public School, Bathinda Assignment - Class Vii (S.S.T) Ch-3 (History)Bachittar SinghNo ratings yet

- MC NAVEDTRA 15010A (Basic)Document374 pagesMC NAVEDTRA 15010A (Basic)MCClifford_DavisNo ratings yet

- Octopath Traveler - COMBINED PDFDocument172 pagesOctopath Traveler - COMBINED PDFIhmahnthropeus Bjørn RagnarNo ratings yet

- History BrochureDocument2 pagesHistory Brochuresaroso0708No ratings yet

- Firestorm Base RulesDocument16 pagesFirestorm Base RuleskarlNo ratings yet

- The Routledge Atlas of Russian History, 4th Edition (Martin Gilbert)Document327 pagesThe Routledge Atlas of Russian History, 4th Edition (Martin Gilbert)Pavle Dragicevic100% (5)

- AsdDocument42 pagesAsdtmp2ans tmp2ansNo ratings yet

- Hercules CookbookDocument108 pagesHercules CookbookTim CostaNo ratings yet

- Bix'n Andy Trigger Installation & Care InstructionsDocument8 pagesBix'n Andy Trigger Installation & Care Instructionsrob256789No ratings yet

- 303 Ammunition HeadstampsDocument44 pages303 Ammunition Headstampset pendarNo ratings yet

- Henkel at Work in The Defense IndustryDocument7 pagesHenkel at Work in The Defense IndustrydatkoloNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Raiders of Sulu SeaDocument9 pagesModule 6 Raiders of Sulu SeaadoygrNo ratings yet

- Indo-Pacific PolicyDocument18 pagesIndo-Pacific PolicyRameen AhmedNo ratings yet

- Kalashnikov-AK-47 Weapon Identification SheetDocument1 pageKalashnikov-AK-47 Weapon Identification SheetAmmoLand Shooting Sports News100% (2)

- Contoh Soal Portal - CrossDocument6 pagesContoh Soal Portal - CrossAlben's ChannelNo ratings yet

- Haptic Media Studies - 1461444817717518Document10 pagesHaptic Media Studies - 1461444817717518Ivy RobertsNo ratings yet

- Santiago Alvarez The Katipunan and The Revolution Memoirs of A GeneralpdfDocument3 pagesSantiago Alvarez The Katipunan and The Revolution Memoirs of A GeneralpdfVanessa Kate VelardeNo ratings yet

- խնդրառություն համաձայնությունDocument16 pagesխնդրառություն համաձայնությունVahe DabaghyanNo ratings yet

- Gun DrawingsDocument1 pageGun Drawings이재원No ratings yet

- Ghar Bahal SamjautaDocument3 pagesGhar Bahal Samjautaprog.loverboyNo ratings yet

- English Task Chapter 11: Cut Nyak DhienDocument7 pagesEnglish Task Chapter 11: Cut Nyak Dhien02 Felysitas Yanet TariNo ratings yet

- Dmitry Glukhovsky - Metro 2033Document300 pagesDmitry Glukhovsky - Metro 2033Gabriel Strugała0% (1)

- Workouts and Techniques That Help With Drownproofing (SAFELY) - Stew Smith FitnessDocument21 pagesWorkouts and Techniques That Help With Drownproofing (SAFELY) - Stew Smith Fitnessherbert roganNo ratings yet

- tamurkhanQA PDFDocument5 pagestamurkhanQA PDFJames Phoenician TurnerNo ratings yet

- Mil DTL 70599BDocument58 pagesMil DTL 70599BA. Gustavo F. LimaNo ratings yet

- Panama Canal - FinalDocument25 pagesPanama Canal - FinalTeeksh Nagwanshi50% (2)

- Warner MDocument384 pagesWarner MkVEGA100% (1)

- Bahur Ul Ghumma Part - 2Document989 pagesBahur Ul Ghumma Part - 2Sayyed Raoshan Rezavi maoranwiNo ratings yet

- Ancient Warfare 2021-07-08Document60 pagesAncient Warfare 2021-07-08BigBoo100% (6)

- Lotto Catalogue 2019Document24 pagesLotto Catalogue 2019ZakcretNo ratings yet