Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Neotropical Cervidology - 11

Neotropical Cervidology - 11

Uploaded by

sgallinatessaroOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Neotropical Cervidology - 11

Neotropical Cervidology - 11

Uploaded by

sgallinatessaroCopyright:

Available Formats

101

CHAPTER

11

WHITE-TAILED DEER Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann, 1780)

Authors: SONIA GALLINA, SALVADOR MANDUJANO, JOAQUN BELLO, HUGO FERNANDO LPEZ ARVALO, MANUEL WEBER Associate Editor: MARIANO GIMENEZ

GENERIC SYNONYMY (Smith 1991) Genus Odocoileus Rafinesque, 1832, Cervus Exlreben 1777: 294 not Cervus Linneus 1798 Dama Zimmermann, 1780. Type species Dama virginiana Zimmermann not Dama Frisch Mazama Hamilton-Smith, 1827b:314. Odocoileus Rafinesque, 1832 :109. Type species Odocoileus speleus Rafinesque by monotypy Dorcephalus Gogler, 1841:140. Cariacus Lesson, 1842. Proposed as a group (subgenus) of Cervus Oplacerus Haldeman, 1842:188. Replacement name of Mazama Hamilton-Smith, 1827 Reduncina Wagner, 1844:377. Macrotis Wagner, 1855:368. Proposed as a subgenus of Cervus Eucervus Gray, 1866:338. Type species Cervus macrotis Say Coassus Gray, 1874:332 Otelaphus Fitzinger, 1873:356. Replacement anme for Macrotis Wagner, 1855 Gymnotis Fitzinger, 1879a:343. Type species Gymnotis wiegmanni Fitzinger by monotypy. Odocoelus Allen, 1901:449. Unjustified emendation of Odocoileus Rafinesque Odontocoelus Sclater, 1902:209. Unjustified emendation of Odocoileus Rafinesque Palaeoodocoileus Spillmann 1931:30. Type species Palaeoodocoileus abeli Spillmann by original designation. Protomazama Spillmann 1931:41. Type species Protomazama aequatorialis Spillmann by monotypy. Aplacerus Hall and Kelson 1959:1003. Incorrect subsequent spelling of Oplacerus Haldeman, 1842 SPECIES SYNONYMY (Whitehead 1993:483) Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann), 1780. Type locality Bewohnt in Carolina,USA. Cervus dama americanus Erxleben,1777 Cervus virginianus Boddaert, 1785. Type locality Virginia, USA. Cervus clavatus H. Smith, 1827 Cervus (Mazama) virginianus H. Smith, 1827 Cervus (Mazama) clavatus H. Smith, 1827

DIXON

Odocoileus spelaeus Rafinesque, 1832 Mazama virginiana Jardine, 1835 Dorcelaphus virginianus Gloger,1841 Cariacus virginianus Lesson,1842. Type locality Camp Crittenden, Sta. Cruz, Co., Arizona. Reduncina virginiana Fitzinger, 1873 Cervus (Cariacus) virginianus Herrick,1892 Cariacus americanus Bangs, 1896 Dorcelaphus americanus Rhoads,1897 Mazama americana Lydekker, 1898 Odocoileus americanus Miller, 1899 Mazama (Dorcelaphus) americana Lydekker,1901 Odocoileus virginianus Stone and Cram,1903 Odontocoelus americanus Elliot, 1904 Mazama (Odocoileus) virginianus Lydekker,1914 COMMON NAMES Spanish: North America: Mxico: acuillame, venado, venado cola blanca, venado saltn, venado real. Central America: venado cola blanca, amap, ciervo de cola blanca, ciervo virginiano, ciervo cola blanca; Costa Rica: venado cola blanca. South America: Colombia: venado coliblanco, venado cola blanca, venado de cornamenta, venado de pramo, venado llanero, venado de racimo, venado blanco, taruca, ciervo, cierva, cuerva, ciervita, venado sabanero, venado carameludo o caramerudo, venado de ramazn, venado reinoso, venado cachiliso, venado cachiforrado, venado cachienvainado, venado grande, cucampo. cariacou, cariac, cariacus; Per: Lluich; Venezuela: venao English: white-tailed deer Portuguese: veado-galheiro French: Guyana: Biche de Cayenne; biche de Louisiana, bina hert Native names (Indigenous): Apeese-mongoose, watai-ush (Cree), squinator, tah-chah-seentay-skah (Sioux); in Mexico: mazatl (Aztec),ceh,uac nac, keej, yalem keej (fawn), tankelem keej (yearling), nojoch keej (adult, Mayan names); Axuni (Tarasco), Guej (Lacandon), Macha (Huichol), muxati (Coras), phatehe (Otomi; Davila 1928 cit. Valenzuela 1991). In Colombia (Rodrguez-Mahecha et al. 1995): Skarama, Sawya, Mejaca ama / Saway, Ejaca jama, Chomquet, Ovbi, Edma (for juveniles),

102 WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

Odocoileus virginianus osceola (Bangs, 1896). Type locality Citronelle, Citrus county, Florida, USA. Odocoileus virginianus peruvianus (Gray, 1874). Type locality Ceuchupate, Per. Odocoileus virginianus rothschildi (Thomas, 1902). Type locality Island of Coiba, Veraguas, Panam. Odocoileus virginianus seminolus Goldman and Kellog, 1940. Type localityten miles northeast of Everglades, Collier county, Florida, USA. Odocoileus virginianus sinaloae. Allen, 1903. Type locality Escuinapa,southern Sinaloa, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus taurinsulae Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality Bulls Island, Charleston County, South Carolina, USA. Odocoileus virginianus texanus (Mearns, 1898). Type locality Fort Clark, Kinney County, Texas, USA. Odocoileus virginianus thomasi Merriam, 1898. Type locality Huehuetan, Chiapas, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus toltecus (Saussure, 1860). Type locality Orizaba, Veracruz, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus tropicalis (Cabrera, 1918). Type locality La Mara, en el Valle del Dagua, Colombia. Odocoileus virginianus nemoralis (Hamilton-Smith, 1827). Type locality restricted to Central America, round the Gulf of Mexico to Surinam; further restricted to From Honduras to Panam (Lydekker, 1915). Odocoileus virginianus ustus (Trouessart, 1910). Type locality El Pelado, north of Quito (4,100 m), on the border with Colombia. Odocoileus virginianus venatorius Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type localityHunting Island, Beufort County, south Carolina, USA. Odocoileus virginianus veraecrucis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality Chijol, northern Veracruz, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus virginiana (Zimmermann, 1780). Type locality Wisconsin, USA. Odocoileus virginianus yucatanensis (Hays, 1872). Type locality throughout Yucatn and the southern part of Mxico. Note to the reader: This chapter is an attempt to summarize the most relevant information on the neotropical subspecies and populations of white-tailed deer. While recognizing that, in the northern hemisphere, it is one of the most thoroughly studied species of large mammals, this chapter provides little information on the species in the United States or Canada. MORPHOLOGICAL DESCRIPTION The white-tailed deer is a polytypic species that has become well adapted to different environments. This diversity is reflected in body weight, external dimensions, coat coloration, antler growth and assorted physiological, biochemical and behavioral distinctions. In general, the color is darker in the humid, forested areas and paler in the drier, more open brushland, reddish in subtropical and tropical environments (Baker 1984). In the northern hemisphere they undergo two complete molts per year: the summer coat consists of short, thin, wiry hairs and

SECTION 2

Quennali (for individuals with small antlers),Awebi, Agbi, Agebi, Nerri: Curripaco; Rrama, Nam, Huey, Chichica, Guahaki, Chuntahe, Sunday, Uase, Kusaru, Vima, Viisa, Irrama, Amusha. SUBESPECIES: Smith (1991) Odocoileus virginianus acapulcensis (Caton, 1877). Type locality Acapulco, Guerrero, Mxico Odocoileus virginianus borealis (Miller, 1990).Type locality Booksport, Maine, USA. Odocoileus virginianus cariacou (Boddaert, 1784). Type locality Guyane, coastal French Guiana Odocoileus virginianus carminis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality Botellas Can, Sierra del Carmen, northern Coahuila, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus chiriquensis (Allen, 1910). Type locality Boquern, Chiriqui, Panam Odocoileus virginianus clavium Barboyr and Allen, 1922. Type locality Big Pine Key, Florida, USA Odocoileus virginianus couesi (Coues and Yarrow, 1875). Type locality Rancho Santuario, northwestern Durango, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus curassavicus (Hummelinck, 1940). Type locality Island of Curacao. Odocoileus virginianus dacotensis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality White Earth River, Mountrail Country, North Dakota, USA. Odocoileus virginianus goudotti (Gay and Gervais,1846). Type locality vits dans les regions elevees de la Nouvelle-Grenade. Odocoileus virginianus gymnotis (Wiegmann, 1833). Type locality British Guiana. Odocoileus virginianus hiltonensis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality Hilton Head Island, Beaufort County, South Carolina, USA. Odocoileus virginianus leucurus (Douglas, 1829). Type locality the districts adjoining the river Columbia, USA Odocoileus virginianus macrourus (Rafinesque, 1817). Type locality Mer Rouge, Morehouse county, Louisiana, USA. Odocoileus virginianus mcilhennyi Miller, 1928. Type locality near Avery Island, Iberia Parish, Louisiana, USA Odocoileus virginianus margaritae (Osgood, 1910). Type locality vicinity of Puerto Viejo, Margarita Island, Venezuela. Odocoileus virginianus mexicanus (Gmelin, 1788). Type locality Valley of Mxico, Mxico Odocoileus virginianus miquihuanensis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality Sierra Madre Oriental, near Miquihuana, southwestern Tamaulipas, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus nelsoni Merriam, 1898. Type locality San Cristobal, highlands of Chiapas, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus nigribarbis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality Blackbeard Island, McIntoch County, Georgia, USA. Odocoileus virginianus oaxacensis Goldman and Kellogg, 1940. Type locality mountains 15 miles west of Oaxaca, Mxico. Odocoileus virginianus ochrourus Bailey, 1932. Type locality Coolin, south end of Priest Lake, Idaho, USA.

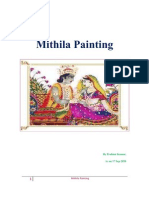

GALLIANA ET AL. 103 varies from red-brown to bright tan; the winter coat varies from blue-gray to gray-brown and has longer, thicker and more brittle hairs (Smith 1991). In the southern hemisphere, the high Andean populations may retain a grayish pelage year-round, while tropical whitetails may keep the tawny, reddish phase (Baker 1984). Fawns have a reddish-brown with white dorsal spots that disappear at 3-4 months of age (Hesselton and Hesselton 1982). climates; in tropical white-tailed deer, this gland disappears irrespective of aridity. South American forms have smaller antlers, shorter tails, and more vestigial canines and are thus more primitive than northern deer (Brokx 1985; cited by Geist 1998). North and South American white-tailed deer are deemed to be a single species, Odocoileus virginianus. Molina and Molinari (1999) used principal components and cluster analyses to compare crania and mandibles of Venezuelan and North American forms. They found that (1) Venezuelan and North American Odocoileus differ greatly from each other; (2) differentiation of groups within Venezuelan exceeds that within North American; (3) the most divergent Venezuelan Odocoileus are those from Margarita Island and the Mrida Andean highlands; (4) the Margaritan Odocoileus does not differ in mandibular shape from its lowland congeners, but differs appreciably from other Venezuelan Odocoileus in having smaller mandibles and in cranial-mandibular characters; (5) the Mrida Andean Odocoileus contrasts markedly with other Venezuelan congeners in mandibular shape and cranial characters; (6) the remaining Venezuelan Odocoileus constitute a single group; (7) within this group, individuals from the Caribbean coast have larger mandibles and differ in some cranial characters. Thus, Molina and Molinari (1999) propose that (a) Venezuelan and other Neotropical Odocoileus are not conspecific with O. virginianus; (b) Margaritan and Andean forms are distinct species: Odocoileus margaritae and Odocoileus lasiotis, respectively; (c) the remaining Venezuelan forms must be included within one species, Odocoileus cariacou; (d) Caribbean coast Odocoileus may represent an undescribed subspecies of O. cariacou. Brokx (1984) proposed for Colombia: O.v. goudotii: Gay and Gervais, 1846, in the Colombian Andes; O.v. ustus Trouessart, 1910, Ecuatorian Andes and maybe South of Colombia; O.v. tropicalis: Cabrera, 1918, at Western of the Cordillera Occidental, Pacific coast of Colombia, it seems to be extinct (Hernndez-Camacho et al. 1992); O.v. apurensis: Brokx 1972, at Eastern of Colombian Andes, Eastern Llanos and Amazona. Smith (1991) did not consider the subspecies O.v apurensis , and its distribution is attributed to O.v. goudotii. The population at caribbean lowlands, from Guajira to Cordoba department is attributed to O.v.curassavicus: Hummelink 1940 (Lpez-Arvalo and GonzlezHernndez 2006). GENETICS Barragn (2002) working with captive animals found all individuals analyzed presented a complement composed by 2n=70 chromosomes. The fundamental number (FN) found for this species was 74 (66 x 1 + 2 x 2 + sexual chromosomes x 2). The IC and RB for pair one, permitted classified as submetacentric (IC=36.8 4.9 and RB=1.77 0.36). In the case of the other autosomes (pair 2-34) the IC was cero (0) and the RB (~), and were classified as autosomes telocentric (Fig. 2). Based on mtDNA data, Moscarella et al. (2003) concluded that Venezuelan white-tailed deer do not warrant

SECTION 2

Figure 1 - Male with growing antlers, with velvet, (O. v. veraecrucis) in captivity (Photo: Alberto GonzlezRomero).

External body measurements of adult males varies for each subspecies. The range of measurements is as follows: total length 104-240 cm; length of tail, 1036.5 cm; length of hind foot, 27.9-53.8 cm; height at shoulder, 53.3-106.7 cm; condylobasal length of the skull, 19.8-32.2 cm (Taylor 1956). Adult males weigh from 90 to 135 kg, females weigh 20-40 % less in USA, but these values diminish in the tropic. Adult deer in the Florida Keys or Coiba Island may weigh 22.5 kg (Halls 1978). Antlers are found only on males from April through February, but these dates change with latitude. The metatarsal gland reaches a maximum length of about 4.1 cm, but it seems to diminish with decreasing latitude. In Venezuela, Brokx (1984) found O.v. gymnotis lacking the glands completely. Dental formula: I=0/3, C=0/1, P=3/3, M=3/3, total=32. Among the 38 subspecies there is a wide variation in size. The largest forms are found in the northern hemisphere (with some exceptions as O.v. clavium) and the smaller in the southern hemisphere. The largest of South American subspecies is O.v. cariacou of Brazil which has a shoulder height of about 80 cm. The smallest is the white-tailed deer of Margarita Island, Venezuela (O.v. margaritae), which stands only about 60 cm. The majority of white-tailed deer living at subtropical and tropical climates is very small, with bucks weighing less than 50 kg and does less than 35 kg. Subspecies from the savannas of Venezuela and Texas appear to have shifted toward classic open-landscape adaptations: they are more sexually dimorphic in weight than are forms from forest, dense shrubs, and coastal swamps, and they have larger, more complex antlers and bigger tails. The metatarsal gland increases in size with increasing aridity and seasonality of

104 WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

During the Spanish Conquest and colonial periods, many spaniards were amazed by the high deer density in Central America. Francisco Solano Astaburuaga, in 1857, wrote: hay muchos ciervos e gamos e corzos ni ms ni menos que los de Castilla, e los indios seores e principales son grandes monteros.... (there are as many cervids and fallow deer and roe deer as at Castilla, and Indians are good rangers...). Costa Rica exported between 1900 and 1933, 86 400 deer skins to the United States, England, France and Germany (Sols-Rivera and Brenes 1987). The archeozoological studies made in the Eastern Cordillera of the Colombian Andes have recorded the species as present in the area 12.000 years ago, as well as related evidence of small groups of hunters- gatherers in the Paleoindian Stage, Preceramic or Litic Stage, 3.000 years ago (Correal and Van Der Hammen 1977; Rincon 2003). More recently the Spanish chronicles of Indians in the Nuevo Reino de Granada indicated the deer presence in the paramos of the cordillera oriental as in the Colombian Llanos; in the paramo of the savanna of Bogota and probably in the Paramos around the area since 1526 to 1763 (Tovar 1988, 1995). Current White-tailed deer is widely distributed, from Canada to South America. It is the premier large mammal in most parts of North and Central America. In southern latitudes deer range from tropical lowlands, approximately at sea level, to mixed forest-brush areas in the Andes of Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, at elevations from 4000 to 4500 meters. In tropical environments at lower elevations, deer is found best in arid and shrub country. In Panama whitetails frequent the drier Pacific side (Baker 1984). Currently in Colombia, deer distribution is fragmented. The causes of this fragmentation are natural factors such as the patchy distribution of the paramos, and antropic causes such as overexploitation and urbanization. White-tailed deer are found in the low land savannas and open forest in Orinoquia and Amazonia; the plains at Caribe from Crdoba to Guajira; the high region of Magdalena, Tolima, Cundinamarca and Huila, and Valle del Dagua. In the Cordilleras Central, and Oriental and the Andes de Nario at 4.000 meters a.s.l. It is no longer found in the Parque Nacional Natural los Nevados, Cordillera Central, where they were recorded for the last time in the 1960s. Their extinction may have been related to diseases caused by cattle (HernndezCamacho et al. 1985). It is still found in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (Alberico et al. 2000; Cuervo et al. 1986; Lpez-Arvalo et al. 2004). KNOWN POPULATIONS In situ populations White-tailed deer population estimated in the United States must be over 11,000,000 of which a third will be in the State of Texas. In Canada the estimation is a half of million deer (Whitehead 1993).

recognition as separate species, but some populations deserve recognition as distinctive evolutionary units worthy of conservation attention. Smith et al. (1986) found that white-tailed deer from Suriname was polymorphic (P) for 10.5% of the 19 loci and had an overall locus heterozygosity (H) of 0.036; in contrast, white-tailed deer from southeastern United States was P = 36.8% and H = 0.078. The genetics distance (D) was 0.173. White-tailed deer from Suriname was closer to red brocket deer Mazama americana (D = 0.063). Also the morphological distance based on sizeunadjusted cranial characteristics, has a comparatively narrow maxillary breadth and was closer to red brocket deer Vaughan et al. (1995) analyzed 18 loci assayed from deer across the three locations (Costa Rica, United States, and Suriname) for multilocus heterozygosity (H), alleles per locus (A), and polymorphism (P). Genetic distances between the three white-tailed deer populations were: Costa Rica vs. United States, D = 0,085; United States vs. Surinam, D = 0.164; and Costa Rica vs. Surinam, D = 0,112.

SECTION 2

Figure 2 - Metaphase and karyotype of a female of whitetailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) with conventional Giemsa stained. In the square section the X Y sexual chromosomes of the male karyotype (Courrtesy Barragn).

DISTRIBUTION The white-tailed deer range from southern Canada, almost all the United States (it is absent in Utah, rare in Nevada and California), Mexico (with exception of Baja California Peninsula), southward to northern South America (Colombia, Venezuela, Guianas, northern Brazil, Northern and Western Peru, and Bolivia, Smith 1991). The area of distribution of white tailed deer in South America covers approximately 5.5 million square kilometers (Brokx 1984), and currently it seems to be expanding. Historical Historically, O. virginianus probably was not as abundant as it is today, but occupied nearly as wide a range. Numbers increased after land clearing and forest exploitation, but then were reduced as a result of overhunting. In Canada, was only in the southern parts of a few provinces (60 North Latitude), to subequatorial South America (15 South Latitude; Baker 1984).

GALLIANA ET AL. 105

SECTION 2

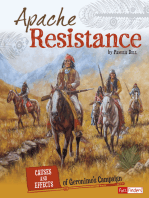

Figure 3 - Distribution map of Odocoileus virginianus. The source of information presented in the map was: Hall (1981) and Smith (1991).

In Mxico, the white-tailed deer is the most widely studied deer (Weber and Galindo-Leal 1995). That is, 75% of 502 deer-related publications between 1850 and 2001 were on white-tails (Mandujano 2004). In particular from the 14 subspecies, the best known are: O. v. texanus, O.v. couesi, and O.v. sinaloae. There are also studies on O. v. mexicanus and O. v. yucatanensis. But seven subspecies: O. v. veraecrucis, O. v. toltecus, O. v. truei, O. v. nelsoni, O. v. oaxacensis, O. v. acapulcensis and O. v. thomasi, are less known. This is critical because all of them inhabit tropical areas (Mandujano and Bello 1998) where rural people commonly practice subsistence hunting. In Mexico, white-tail deer densities varies from 1-20 deer/km2 in the different geographic locations studied (Table 1). In tropical areas, as Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz, Mexico, the results using abundance index show a low value for white-tailed deer (0.025) compared with temazate deer, Mazama temama (0.36) (Bello 1993). In Tabasco, Mexico, the Parque Estatal la Sierra de Tabasco and La Sierra de Tenosique, the index was one and 0.5 respectively (Jess and Bello 2004). Little information has been generating about the current white tailed deer populations in Central America. Mendez (1984) reported a general distribution at Central America countries and its occurrence in some protected areas. Current for Panama in Cerro Hoya National Park, Pacific coast, province of Veraguas and Los Santos, the specie is common (Anam 2007). In Costa Rica, the mean distribution area is in the tropical dry forest, of the Guanacaste and Punta Arenas provinces, where several

reintroductions were made at the end of 80s (Calvopia, 1995, Hernandez 1995, Senz 1995); white tailed deer is abundant at Santa Rosa and Palo Verde national parks (Reid 1997). For Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and Belize, the information about wild populations is not available. In Venezuela, in 1973, there was estimated a population of 10,000 deer in 68,000 ha in El Frio, State of Apure (Lander 1991). The main deer population in the Colombian Andes is found in the Eastern Cordillera, mainly in the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. It is currently reported in six protected areas: the Natural National Parks Cocuy, Chingaza, Sumapaz and Pisba; and the Flora and Fauna Sanctuaries Iguaque and Isla la Corota. Today, the existence of deer in the interandine valleys is in doubt. Preliminary evaluations indicate numerous populations in the Departments of Casanare and Vichada, also in Meta and Arauca. Wild populations are protected in the Natural National Park El Tuparro (Lpez-Arvalo et al. 2004). Some information on the free ranging population in Peru is available. Confined wild populations could exist in several protected areas, such as the national parks Cerros de Amotape, in Tumbes and Piura, Cutervo in Cajamarca, Huascarn in Ancash, Manu in Cusco and Madre de Dios, Tingo Mara in Hunuco, Yanachaga Chermilln in Pasco; the National Reserves of Calipuy in la Libertad, Lachay in Lima, Salinas and Aguada Blanca in Arequipa; and the Historic Sanctuary of Machupiccu in Cusco (Acabape, 2007).

106 WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

Table 1 - White-tailed deer densities estimations (deer/km2) in several locations at the Neotropical region.

SECTION 2

Ex-situ populations In Mexico, it is a common practice to have deer in captivity. There are many UMAS (Unidades para la Conservacin, Manejo y Aprovechamiento Sustentable de la Vida Silvestre or Units for conser vation, management and sustainable use of wildlife) that harbour white-tailed deer. For example, in the State of Yucatan, there are 12 UMAS for deer (Gonzlez-Marn 2002); in Tabasco had more than five UMAS (Mendoza-Castillo and Gamboa-Gonzlez 1993), but currently there are 15 UMAS with Odocoileus (Bello et al. 2009), three of them are zoos (Len-Castro 2000). All the Zoos in Mexico have deer stocks in captivity. Most of Colombian Zoos had deer stocks. During 2004, 250 individuals were found in six zoos and two private farms (Guzmn 2005). The existences of two more farms with 40 individuals were identified although it is

considered illegal. Elsewhere in Latin America, it is little known about captive white-tail deer populations. HABITAT White-tailed deer live in a wide range of habitats from north temperate to subtropical and semi-arid environments in North America, and include rainforests and other equatorial associations, such as deciduous forests and savannahs of Central America and Northern South America (Brokx 1984; Danields 1991; Smith 1991). It is abundant in mixed pine-oak forests of Mexico (Ffolliott and Gallina 1981), and prefers flat sites, such as the mesas or elevated areas, where plant diversity and the available biomass have greater values (Gallina 1994b). They are also found in second-growth forests and thickets and forest-savanna ecotones of Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, El Salvador, Costa Rica and Panama (Mendez 1984).

GALLIANA ET AL. 107 The amount and temporal distribution of precipitation is the ecological limitation in more southern latitudes and lower elevations (Ffolliott and Gallina 1981; Mendez 1984; Villarreal 1999). O. virginianus favour more mesic climates and vegetation within arid regions. In the Andes countries, distribution of the white-tailed deer is not limited by elevation but rather by steep arid habitat and by rainforest on the mountain slopes (Brokx 1984). White-tailed deer is an extremely adaptable species. The species thrives in close association with man and his agricultural and industrial pursuits. Its requirements are met in practically every ecosystem, but it reaches its largest densities in hardwood forests and bushlands (Teer 1991). Delfin (2002) made a habitat evaluation for O. v. mexicanus using the model of Optimal Habitat Unit in a tropical dry forest at the Mixteca Poblana, Puebla, Mexico, and Delfin et al. (2009) with O. v. veraecrucis in the State of Veracruz, Mexico, applying GIS, and considering abiotic and biotic variables: distance to free water, temperature, slope, orientation, vegetation type, protection cover and food, as a preliminary stage to take conservation and sustainable use strategies for deer. Coronel-Arellano et al. (2009) propose to use the standardized vegetation index as a predictive variable of the density of white-tailed deer in temperate habitat sites, and emphasize the importance of this procedure as a potential tool for other areas focusing on the conservation and reintroduction of large carnivores, for which the deer are prey. The white-tailed deer inhabits tropical dry forest in Chamela, located on the Mexican Pacific central coast, which is characterized by both temporal and spatial availability of food, nutrients, and water for white-tailed deer (Mandujano and Gallina 1995b; Mandujando et al. 2004, Silva-Villalobos et al. 1999). In the Biosphere Reserve of Manantln, Jalisco, Mexico, white-tailed deer prefer the cloud forest (Gonzlez-Prez 2003). In tropical evergreen forest, white-tailed deer have benefited from transformed habitats (acahuales) and crops (Jess and Bello 2004). The secondary forests with trees of 6 m high and gentle slopes (11), with a dense shrub cover of 90% (Bello et al. 2004a). The tropical rain-forest has been long considered as a sub-optimal habitat for the white-tailed deer (Leopold 1977). But it was just recently, that more detailed studies of habitat use had been carried out in tropical rain-forests in Mexico (Naranjo 2002; Reyna-Hurtado 2002; Weber 2005). In the arid region of Northeastern Mexico, dominated by the xerophyllous brushland deer habitat preferences were influenced by habitat type, sex and year. Females used the vegetation associations with dense cover (AcaciaCastela brushland). Males however, selected most of the habitat types according to availability, showing preferences for open habitats dominated by Flourensia (Bello et al. 2001a; Gallina and Bello 2000). In arid zones, when weather conditions are good with normal precipitation (more or less than 400 mm annual), the quality and quantity of available forage is a key factor in determining habitat use by deer. However, if drought or predation increases, thermal and hiding cover become relatively more important than forage availability (Bello et al. 2001b, Gallina and Bello 2000). Correa-Viana (1995) found that in Venezuela (paramo Mucubaji) deer preferred open habitats in the valley than pine forest of Pinus radiata (exotic species), slopes of Espeletia and Coloradito Forest (Polylepis rericea). In Colombia, there is little information about deer habitat use. Although in high areas deer used more the Paramo, and the subparamo, and in low proportion the forest (Ramos 1995). In tropical dry forest, deer in semicaptivity used grassland and crops, for the availability of food (Mateus-Gutierrez 2005). In the Andes region, the species is present in seven types of ecosystems proposed by Etter (1998), and four agroecosystems. In the Orinoqua region deer used natural (dry savannas, wet or flooding, and forest) and transformed ecosystems (Romero et al. 2004). In Peru, Barrio (2006) found differences in habitat use between O. v. peruvianus and Hippocamelus antisensis. They seem to separate themselves by altitude and habitat type. SPATIAL USE AND HOME RANGE White-tailed deer occupy a well defined home range, but they are not territorial. Home ranges are influenced by age, sex, density, social interactions, and latitude, season and habitat characteristics. Size of home ranges varies inversely with density and vegetative cover. Annual home range averages 59- 520 ha (Marchinton and Hirth 1984). In Northeastern Mexico, O.v. texanus home range averages 193 ha for females and 234 ha for males (19951998) in a xerophyllous brushland (Bello et al.2004a). The differences noted were between the fawning and reproductive seasons in some years, and were caused by differences in the quantity and distribution of precipitation (Bello et al. 2004b). In the same area, Soto-Werschitz (2000) compared female home range with and without fawns, and the results obtained showed that the females without fawns reduced their home range size during fawning period, meanwhile the females with fawns maintained their home range size, probably because the energetic requirements for lactating period. Individuals belonging to O.v. sinaloae were radiotracked in a tropical dry forest in the Pacific Coast of Mexico (Chamela, Jalisco). The mean distance travelled by a female was 1.5 y 2.6 km/day during the dry and wet season respectively. The home range size was 11 ha and 24-44 ha, respectively. In the dry season a male traveled 2.5 km/day and the home range size in dry season was 26 ha (Snchez-Rojas et al. 1997). Also with the same subspecies, in a cloud forest of the Biosphere Reserve of Manantln, Jalisco, Mexico, a study of six females reported a mean home range size of 14.5 ha during wet season and 16.9 ha in the dry season (Gonzlez-Prez 2003). In Chamela, Jalisco, Mexico, deer prefered the tropical dry forest all the year, mainly during the wet season as foraging area, because the availability of palatable plant species (density and biomass of foliage, and the presence of Spondias purpurea important fruits in the dry season),

SECTION 2

108 WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

In the arid zones of Mexico and USA, deer select as much as 83% shrub species (Villarreal 1999). More information on the nutrition and related aspects, of whitetailed deer in Northeastern Mexico, are described by Ramrez-Lozano (2004). As an example, plant species consumed by deer have high crude protein (some more than 20%). Considering the use of water sources in arid areas of Northeastern Mexico where water management is intense, the deer are found distances greater than 200 m from the sources (Bello et al. 2001b; Bello et al. 2003b). According with Arceo et al. (2005), in the tropical dry forest of Chamela, Jalisco, Mexico, the main families Euphorbiaceae, Leguminosae, Convolvulaceae, and Sapindaceae accounted for 80%, 64%, and 37% of the diet during the rainy, transition and dry season respectively. The mean percentage of protein estimated for plants consumed was 14.2%. The percentage of free nitrogen extract was estimated in 49.0% and the mean annual fiber percentage was 24.2%. An important food resource in this habitat was the fruits of Spondias purpurea (Anacardiaceae) (Mandujano et al. 1994). These fruits constituted the 13% of the diet during dry season (Arceo et al. 2005) and could contribute between 2 to 30 liter/ ha of water depending on annual fruit production (Mandujano and Gallina 1995a). In the tropical semi-deciduous rain-forest of southeastern Mexico (Calakmul Region) the white-tailed deer was found to feed on the fruits, leaves and stems of 26 species of trees, palms and bushes. The zapote tree (Manilkara sapota) can be considered a keystone plant resource for deer and other wildlife in this region of Mexico (Weber 2005). This species also ate large amounts of fruits during the wet season (June to November). Considerable dietary overlap exists between the whitetailed deer and Mazama pandora during this period (Weber 2005). Di Mare-Hering (1991) at San Lucas Island, Puntarenas, Costa Rica, found that major forage plants were browse (dry season) and forbs (wet season). Diet diversity and equitability were high, ranging from 35 to 72%, with the highest values during the dry season and the lowest in the wet season. Foods eaten were in general of lower quality than temperate zone forages. Some of the forage plants are known to contain secondary compounds. In Colombia, deer diet was studied by two methods: direct observations (captivity) in the dry forest (MateusGutierrez 2005) and in wild conditions in the Pramo (Blanco and Zabala 2005; Mora and Mosquera 2000; Ramos 1995) and also by surveys obtained with local people and researchers in natural savannas and paramos (Blanco and Zabala 2005; Gonzlez 2001). Deer is an opportunistic forager eating crops in the paramo, mainly beans, potatoes and maize (Blanco and Zabala 2005). REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY The mean gestation period is about 202 days (Halls 1978) but differs among subspecies, ranging from 187 to 222 days. Litter size ranges from one to three (twins are common), and is related to genetic factors and nutrition (Verme and Ullrey 1984). Neonates have spotted

and of high nutritional quality; also the low predation risk compared with the tropical semi-evergreen forest that develop along the streams and rivers in the area (Mandujano et al. 2004), where there are found less consumed plants, with higher fiber contents, lignin and alcaloids (Silva-Villalobos et al. 1999), and more used by predators (Lpez-Gonzlez et al. 1998; Nez and Miller 1997). In Costa Rica, Senz-Mndez and Vaughan-Dickhaut (1998) reported the mean daily distance traveled as 3.1 km (2.8-3.6 km). The average daily home range was 18.3 ha. Deer used 8 to 11 habitat types of the 14 available. Habitat utilization was significantly different between the dry season and the wet season. The most utilized habitats were grazing land, forest plantations (Pithecelobium saman), cultivated land (sorghum and fruits), riparian vegetation, chaparral, jaraguales and guacimales (Guazuma ulmifolia). Rodrguez-Senz et al. (1985) found that the size of the home range (two females) varied between 7.7 and 14.8 ha. The mean distance travelled daily was 1.6 to 1.7 km. In other study Calvopia-Oate (1990) analized ecological aspects of deer reintroduction in some localities of Costa Rica. The mean distance of dispersion was 6 km (3-11 km) from the liberation site. The mean home range size was 323 ha (25-530 ha). In Colombia, information about deer movements was obtained with animals in captivity (Camargo-Sanabria 2005; Mateus-Gutirrez 2005) and reintroduced individuals in cattle ranches (Gmez-Giraldo 2005). The results obtained in captive conditions along a year of radiotracking of two animals were 26 and 96 ha (male), and 17 and 45 ha (female). In the case of the three individuals reintroduced in cattle ranches, the values registered were larger 114 and 378 ha, the largest size was for males (GmezGiraldo 2005). In Venezuela, the home range estimated for two deer reintroduced in a ranch was 80 ha, using more the gallery and caducifolious forests (Correa-Viana 2000). FEEDING ECOLOGY White-tailed deer are ruminants with a typical compound stomach (rumen, reticulum, omasum and abomasum), being a selective feeder that chooses plants and plant parts with considerable discrimination. It is considered a browser that prefers shrubs and trees, although consumes a variety of foods including sedges, fruits, nuts, forbs, mushrooms, and some grasses. Diet changes with regions and seasons (Danields 1991; Gallina 1993; Gallina et al. 1981; Mandujano et al. 2004). It is considered an opportunistic concentrate feeder (Table 2). Deer at La Michila biosphere Reserve in Durango, Mexico preferred shrub (51%) and tree species (32%). Clemente (1984) in the State of Aguascalientes, Mexico, found a consumption of 49% of forbs and 45% of shrubs in summer; 15% forbs, 35% fruits and 39% shrubs in autumn; and 20% forbs, 61% shrubs and 18% trees during winter. The crude protein decrease in the chemical analysis of deer diet: 8.94, 7.87 and 6.32% in summer, autumn and winter respectively. The dry matter consumption was estimated for a doe (weight of 45 kg), as 2.29 kg in summer, 1.85 kg in autumn and 1.20 kg in winter.

SECTION 2

GALLIANA ET AL. 109

Table 2 - Comparison of white-tailed deer diet in different habitats and countries.

SECTION 2

Rainy season includes spring, summer and fall in temperate region, and dry season includes winter.

References: White tail deer diet in different habitat at the Neotropical region according to: 1Branan, Werkhoven, and Marchinton 1985; 2Granado 1989; 2Danields 1987; 3Di Mare 1994; 4Weber 2005; 5Arceo, Mandujano, Gallina and Prez-Jimnez 2005; 6 Clemente-Snchez 1985; 7Gallina, Maury and Serrano 1981; 7Gallina 1993; 8Ramrez-Lozano 2004; 8Villarreal 1999.

pelage that is lost three months after birth. Females usually breed at the age of 1.5 years, while males attain sexual maturity by the age of 1.5 years. The ultimate determinant of the breeding season is availability of adequate nutrition, which is cued by photoperiod (Verme and Ullrey 1984).

In northern subspecies it occurs in autumn and winter (it changes with the latitude), but reproductive cycles of South American white-tailed deer are inadequately known (Brokx 1984). In the tropics, breeding can be year-round with peaks in certain seasons (Geist 1998).The fawning

110 WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

and Vaughan-Dickhaut (1985) reported the fawning season in April and May in Guanacaste, Costa Rica, at the beginning of the rainy season. Blounch (1987) reported that, in the Colombian Llanos, the fawning season was from September to March, with a peak in December. Males with antlers were present all the year. The same pattern was observed in the high lands, but with a high frequency of births in December, January and February (Blanco and Zabala 2005). According with Guzmn (2005) the reproductive cycle in captive males is approximately one year long (12-13 months). The antlers are normally shed from November to January, but not in all places. The gestation time in captivity was estimated to be 5-6 months, with the probability of one or two births in the year. The probability of having twins increases with the females age. The first oestrus (n=12) varied from 176 days (0.5 years) to 1205 days (3.3 years) with a mean of 532 days (1.5 years). Brokx (1972b) found that white-tailed deer does are continuously polyestrous in the llanos region, yet the main rut of adult bucks occurs in the dry season (January to May). A secondary peak of births was evident in February and March, and attributed to sexual activity of young maturing bucks in the rainy season. Does readily ovulate after parturition, and probably reproduce at intervals shor ter than one year. The apparent lack of synchronization in breeding biology is therefore attributed to accelerated reproduction and locally selective forces. BEHAVIOUR Deer behaviour, in a sample of 26 females and 13 males in captivity, was studied by Rosas-Alvarado (1990, 1994), in Chapultepec Zoo (Mexico City). The author identified 106 behavioural patterns and described the ethogram for the species. Serio-Silva (1999) describes the changes of behaviour in white-tailed deer as a consequence of exposure to humans (presence/absence) in two different kinds of enclosed plots located in Banderilla and Xalapa, in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. His results suggested changes in the feeding behaviour. The species is crepuscular, but activity varies according to several environmental variables, mainly the distribution and amount of precipitation (Gallina et al. 1998; Gallina et al. 2003; Marchinton and Hirth 1984). White-tailed deer form two basic social groups: family groups centered around a matriarch (the mother and female fawns of previous generations) and fraternal groups made of adult and occasionally yearling males (Marchinton and Hirth 1984). Mixed groups occur only during the mating period. It is possible to find mixed feeding groups, but these assemblages are temporary and they do not form social groups. Dominance hierarchies minimize conflicts and avoid aggression within groups, reducing energy expenditure and risk of injury (Marchinton and Hirth 1984). Social organization and behaviour vary in relation to habitat characteristics, so group size is inversely related to density cover (Hirth 1977; Mandujano and Gallina 1996). Sexual segregation and the relation with diet quality were studied by Buenrostro (2005) in a tropical dry forest at the Sierra de Huautla, Morelos, Mexico. She found that females

period for O.v. gymnotis occurs mainly from July to November (rainy season), but a second peak occurs during February and March (dry season). The fawning peak of O.v. apurensis occurs mainly from November to February, perhaps in adaptations to heavy rains and widespread flooding on the low llanos. In Peru, fawning varies regionally but generally occurs from January to March (Brokx 1984). In North America the rutting season takes place from October to early December, reaching its height in November. In South America the season of the rut varies according to locality. In Peru most rut activity seems to take place in February and March. During the rut the bucks run with an individual doe for a day or two before moving off in search of another doe in oestrus. In Mexico, a study in captivity showed that the breeding season in O.v. couesi, began in December and end in March (Rosas-Becerril 1992). In a tropical dry forest of Chamela, deer (O.v. sinaloae) breed between November and January, and fawns born between June and August (Mandujano et al. 2004). Martinez-Romero (2004) using estradiol and progesterone levels in captive females and testosterone in males of O.v. mexicanus, in Puebla, Mexico, found that the reproductive season started in November but copulation did not take place until January. In captivity, in Chapultepec Zoo at Mexico City, deer breeding season was from October to December (Rosas-Alvarado 1990). Compared with other aspects on the ecology of this species, the reproductive biology of white-tailed deer has been little studied in Mexico. Many aspects of the reproduction of the Coues white-tailed deer (O.v. couesi) were studied in Durango, Mexico, both in captivity and in the wild (Galindo-Leal and Weber 1998; Weber 1992). The average fawning date was February 12 th. The reproductive season is approximately 95 days long, starting in January and finishing at the beginning of April. The interval between oestrus is 26 days ( 3.5 days). Behavioural oestrous last 18 hours ( 1.5 hours). Fawns are born in August and September after a gestation period of 198 to 200 days (Rosas-Becerril 1992; Weber and Galindo-Leal 1992). Males start the rut in November with some behavioural and physiological changes and this period finishes in May with the shedding of the antlers. The antler velvet is shed during the first two weeks of October. The largest testicular diameters were recorded in February, the same time that most females are found in oestrus (Weber and Galindo-Leal 1995) Growth and weight gain patterns of fawns have been also studied in central and northern Mexico with average weight gains of 225 gm/day for naturally reared fawns (Weber and Hidalgo 1999). In tropical regions of Mexico, the white-tailed deer tend to be much less seasonal in its reproduction than in temperate environments (Galindo-Leal and Weber 1998). However, very little is known about seasonality and other aspects of reproduction of this species in the tropics. In the Calakmul Region of Campeche, Mexico, very young fawns and/or fetuses and males with velvet antlers have been observed almost year-round, suggesting a lack or reproductive seasonality at this latitude. McCoy-Colton

SECTION 2

GALLIANA ET AL. 111 consumed a higher quality diet (with high fecal nitrogen values) compared to males. In a Cloud Forest at the biosphere Reserve of Manantln, Jalisco, Mexico, six females were radiotracked, finding a bi-modal daily activity cycle (Gonzlez-Prez 2003): 09:00-12:00 h and 19:00-00:00 h. Deer in arid zones were more active during crepuscular hours: 17:0021:00 h and early in the morning 05:00-09:00 h. During the breeding season, deer were active at all hours of the day. A negative correlation was found between activity and temperature (Gallina et al. 2003). Distances traveled per day by deer (O.v. texanus) were significantly different between years (x = 7,016 354m). Significant differences in season-year interaction were detected, this could be explained by significant differences in seasonal precipitation (Bello et al. 2003a; Bello et al. 2004b). Significant relationships were found between precipitation and distance traveled per day, as the former increased, so did the latter (Bello et al. 2004b). Deer activity patterns were obtained by radiotracking 14 animals equipped with collars with activity sensor, in Northeastern Mexico (Corona 1999; Gallina et al. 1998, 2003; Mandujano et al. 1996; Prez et al. 1996). Deer spent less time feeding (11% in 1995, 16% in 1996) and more time bedding (57% in 1995, 64% in 1996). Although males and females had different energetic requirements along the year, there were no significant differences in their activity patterns (Gallina et al. 1998; Prez et al. 1996). Deer were more active during the breeding season when searching for a mate, and less active during postreproductive or gestation season, which coincides with the dry season. Delfin et al. (1998) found than deer travelled less distances during this season, when temperatures were high, maybe to reduce energetic consumption. During the fawning season, deer activity increases. This season coincides with the rainy season, when there is a considerable increase in the quantity of forage availability. The characteristics of the diurnal bedsites used by deer in semiarid zones with xerophyllous brushland that are hot (> 40C) and dry (< 400 mm/year rainfall) must be taken into consideration both for deer conservation and the appropriate management of their habitat. Several habitat variables were measured at the bedsites: shrub species, height, volume, thermal and protection cover, forb and grass cover, temperature and humidity. Randomly selected sites were also described to compare the habitat variables and detect any preferences. Shrub cover, height and volume were higher in the bedsites. There were seasonal differences in site selection: males selected bedsites under shrubs with more thermal cover, volume and height. During the fawning season females looked for more protective cover (Contreras 2000). Rodrguez-Ramrez (1987) studied the composition of size, social group and the reproductive behaviour of deer in the Isla San Lucas, Costa Rica. The family groups were composed of the mother and fawns of that year, adult males were solitary. Adult males and females formed mixed groups during fawning and breeding season, but only in the later season were there bonds between the sexes. Correa-Viana (1995) reported that deer in the paramo Mucubaji, Venezuela, had two activity peaks: at 0900 h and in the sunset. In Venezuela, Correa-Viana (2000) reintroduced two deer in a ranch of Jaimero, Portuguesa, Venezuela, and studied their movements, activity and habitat use. There is some information about deer behaviour in Colombia, obtained by radiotracking two deer. In semicaptivity the reintroduced deer presented three activity periods (Camargo-Sanabria 2005), and later changed to a binomial pattern as in wild animals (Mateus-Gutierrez 2005). In captivity the dominance relationships were: adult males dominated adult females, and these females dominated the juveniles (Camargo-Sanabria 2005). In the Paramo region of Colombia, deer spent 55% of their time for feeding in the morning hours, 22.8% ruminating, and 21.6% resting. Deer used only 0.1% of the time for drinking (Mora and Mosquera 2000). White-tailed deer live in family groups, and herds up to twenty are often observed in high-density areas on treeless plains of the llanos. In savannas, deer are sedentary, living on rather small, permanent and overlapping home ranges. Permanent water holes are important in seasonally dry habitats. The white-tailed deer grazes in the morning and evening where protected, but becomes strictly nocturnal if harassed (Brokx 1972a). CONSERVATION STATUS In the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Gallina and Lpez Arevalo 2009) O. v. clavium is considered endangered (EN D, a population estimated to number less than 250 mature individuals) and O.v. leucurus as Lower Risk near threatened (LR/nt, a taxa which does not qualify for Conservation Dependent, but which are close to qualifying for Vulnerable, IUCN, 1994). The O.v. mayensis (?) is the only subspecies from Guatemala included on CITES Appendix III. In the tropical dry forest, continued dry years and the hunting of females could have a quickly decreased population size. In the Chamela region of Mexico, jaguar (Panthera onca), puma (Puma concolor) and ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) predates on deer (Lpez-Gonzlez et al. 1998; Nez and Miller 1997). Predation has an important role on deer populations, during fawning, and at the end of the dry season, when individuals might be more vulnerable. Other important factor is poaching or illegal hunting, a common practice used all the year, killing both sexes and all ages (Contreras-Moreno 2008). Although a highly resilient and adaptable species, local extinctions of white-tailed deer due to over-hunting had been documented in sub-optimal habitats with high hunting pressure such as the tropical rain forest of the Calakmul Region (Weber 2002, 2005; Weber and Gonzalez, 2003). Together with the peccaries, deer from the Mazama genus and some caviomorph rodents (i.e. pacas and agouties), the white-tailed deer are the main game species for both subsistence and sport hunters in Meso-america south of the Tropic of Cancer. This species has been subjected historically to a continuously high hunting pressure and yet still remains in most habitats throughout this tropical region. Using a novel technique

SECTION 2

112 WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

easily observed. The same pattern was registered in the Orinoqua, where one can see herds composed up to 30 individuals. In captivity, deer had reproduced successfully. Finally there is a deer management and conservation strategy describing short, medium and long term activities (Lpez-Arvalo et. al. 2004). The main aspects are the need to evaluate conditions in situ of the distribution, population size and home ranges, habitat, hunting activities, educational programs and monitoring. At ex situ level, it is important to have a control of fawning, breeding activities, interchanges between zoos, and veterinarian aspects. The white-tailed deer is one of the most important game animals in Latin America, particularly in: Mxico, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panam, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Peru (Ojasti 1996). Deer in South America is much less abundant now than in the 1940s, and the general decline appears to be the result of indiscriminate hunting, changes in land use and competition with domestic animals (Brokx 1984). ACKNOWLEDGMENT We want to thanks Susana Gonzlez and J. Mauricio Barbanti Duarte for the invitation to write this chapter and give us this opportunity. We are very grateful for the information provided by Javier Barrios and J. Mauricio Barbanti Duarte to improve the distribution map of whitetailed deer in South America, and also to Giordano Ciocheti and Norma Corona Callejas for help us with this map. LITERATURE CITED

ACABAPE, Asociacin de Caza con Ballesta del Per, 2007. El venado cola blanca parte 1. http://ballestaperu.com/ content/view/144/48/ accessed June 3 2007 ALBERICO, M., A. CADENA, J. HERNNDEZCAMACHO, AND Y. MUOZ-SABA. 2000. Mamferos (Synapsida: Theria) de Colombia. Biota Colombiana 1: 4375. LVAREZ, O. A., AND O. A. SALAZAR. 2003. Hematologa y qumica sangunea del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) en cautiverio. Thesis. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogot. ANAM 2007. http://www.anam.gob.pa/parques/ cerrohoyanew.htm, accessed June 3 2007. ARCEO, G., S. MANDUJANO, S. GALLINA, AND L. A. PEREZ-JIMENEZ. 2005. Diversity of diet of white-tailed deer in a mexican tropical forest. Mammalia 69:159-168 BAKER, R.H. 1984. Origin, classification and distribution. Pp.1-18 in White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management (L.K. Halls, ed.). Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA. BARRAGN, K. 2002. Caracterizacin cromosmica de venados cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) (Zimmermann, 1780). Thesis. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogot. BARRIO, J. 2006. Biogeography of Cervidae in Peru. in Advances in Deer Biology (L. Bartos, A. Dusek, R. Kotrba, J. Bartosova-Vichova, eds.). Proceedings of the 6 th

incorporating both GIS/GPS technologies and participatory research with hunters, Weber (2005) found that maximum annual harvests of 0.6 deer/km2 are needed to achieve source-sink dynamics in a heavily hunted subsistence scenario in southeast Mexico. There are differing opinions about the role of the Wildlife Conservation, Management and Sustainable Utilization Units (UMA, Spanish acronym for Unidades de Manejo, Aprovechamiento y Conservacin de Vida Silvestre) for conservation of white-tailed deer in Mxico, so Sanchez-Rojas et al. (2009) emphasize the importance of UMA as a complementary strategy for the conservation and sustainable use of this species in forested areas in the center of the country. The work of Mandujano and Gonzalez-Zamora (2009) shows that most UMA do not have the critical size to support minimum viable populations (MVP) of white-tailed deer, while the Biosphere Reserves, Areas of Protection of Natural Resources, and Protected Areas of Flora and Fauna, are the ANP (Spanish acronym for Natural Protected Areas) which could potentially support the MVP of this species. A recent evaluation suggest a minimum critical area (MCA) of 1,667 to 50,000 ha to support a minimum viable population (MVP) of 500 deer, or 16,670 to 500,000 ha for long-term viability of 5,000 deer, depending on regional deer density. These authors suggest a system of conservation at a regional level in which ANP and UMA are incorporated, assuming source-sink and archipelago reserve models, where connectivity can have an important role in the movement of individuals between populations. Gallina and Escobedo-Morales (2009) analyze the introduction of exotic species in UMA, such as red deer, that could be an important alternative at production level but has not contributed to the conservation of native species and in many cases may have serious negative consequences as competition for resources and possible disease vectors. Therefore, strict control of these exotic species is necessary, as the encouragement of the use and conservation of native wildlife and the revision of the main conservation objectives of UMA. The mammal list of Colombia (Rodrguez 1998), classified the deer specie as vulnerable (VU). Recently, using the UICN criteria each subspecies were categorized: O.v. tropicalis, critical risk (CR), O. v. apurensis, low concern (LC) and O.v.goudotii, O.v. ustus, O.v. curassavicus are data deficient (DD) (Lpez-Arvalo and Gonzlez-Hernndez 2006). Hunting pressure and habitat transformation are the factors that eliminated deer populations from the savannas of Bogota, and around the paramos. It was probably extinct or reduced in numbers in El Nevado del Huila and El Nevado de Purac, in the Andes de Nario and in the Alto Cauca, Valle del Dagua, in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, and in different sectors of Orinoqua, Colombia. The increased interest as hunting trophy made necessary to plan monitoring strategies and activity regulation in Colombia. Other important pressure is feral dogs. In areas like National Natural Park Chingaza, where hunting pressure has diminished, deer population increased notably during the last decade, and now are

SECTION 2

GALLIANA ET AL. 113

International Deer Biology Congress, Prague, Czech Republic. Pp. 172 BELLO, J. 1993. Situacin actual del orden Artiodactyla en la Regin de Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz. Thesis. Facultad de Biologa. Universidad Veracruzana, Mxico. BELLO, J., S. GALLINA, AND M. EQUIHUA. 2001a. Characterization and habitat preferences by white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in Mexico with high drinking water availability. Journal of Range Management 54:537545 BELLO, J., S. GALLINA, AND M. EQUIHUA. 2003a. Comparacin de los movimientos del venado cola blanca en dos sitios con diferente disponibilidad de agua del Noreste de Mxico. Pp. 59-66 in Manejo de Fauna Silvestre en Amazona y Latinoamrica. Seleccin de trabajos V Congreso Internacional. (R. Polanco, ed.). CITES, Fundacin Natura. Bogot. Colombia. BELLO, J., S. GALLINA, AND M. EQUIHUA. 2003b. El venado cola blanca: uso del hbitat en zonas semiridas y con alta disponibilidad de agua del Noreste de Mxico. Pp. 67-76 in Manejo de Fauna Silvestre en Amazona y Latinoamrica. Seleccin de trabajos V Congreso Internacional. R. Polanco (ed.). CITES, Fundacin Natura. Bogot. Colombia. BELLO, J, S. GALLINA, AND M. EQUIHUA 2004. Movements of white tailed deer and their relationship with precipitation in the northeastern of Mxico. Interciencia 29:357-361 BELLO, J., S. GALLINA, M. EQUIHUA, S. MANDUJANO, AND C. DELFN. 2001. Home range, core area and distance to water sources by white tailed deer in northeastern Mexico. Vida Silvestre Neotropical 10:3037. BELLO-GUTIRREZ, J., C.C. GUZMN-AGUIRRE, AND J. SANTOS-ZUIGA. 2004. Aspectos ecolgicos del venado cola blanca en la regin Sierra del estado de Tabasco. Memorias IX Simposio de Venados en Mxico. FMVZ- UNAM. ANGADI. UAEH Pachuca, Hidalgo,Mxico. BELLO-GUTIERREZ, J., F. M. CONTRERAS-MORENO, AND C. E. PEDRERO-HERNNDEZ. 2009. Anlisis de las unidades para la conser vacin, manejo y aprovechamiento de l a fauna silvestre, en el estado de Tabasco in Memorias IV Simposio sobre Fauna Cinegtica en Mxico. Benemrita Universidad Autnoma de Puebla, Puebla, Puebla, Mxico. 194-199 BLANCO, L., AND A. I. ZABALA. 2005. Recopilacin del conocimiento local sobre el venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus), como base inicial para su conser vacin en la zona amortiguadora del Parque Nacional Natural Pisba, en los municipios de Tasco y Socha. Thesis. Escuela de Biologa. Universidad Pedaggica y Tecnolgica de Colombia. Tunja. BLOUCH, R. I. 1984. Northern Great Lakes and Ontario forests. Pp. 391-410 in White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management. (L.K. Halls, ed.). Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA. BLOUNCH, R. A. 1987. Reproductive seasonality of the white-tailed deer on the Colombia llanos. Pp. 339-343 in Biology and Management of the Cer vidae (C. Wemmer, ed.). Washington, D. C. Smithsonian Institution Press. BRANAN, W. V., M. C. M. WERKHOVEN, AND R. L. MARCHINTON 1985. Food habits of brocket and white-tailed deer in Suriname. Journal of Wildlife Management 49: 972-976. BROKX, P. A. 1972a. A study of the biology of the Venezuelan white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus gymnotis Wiegmann 1833) with a hypothesis on the origin of South American cervids. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. BROKX, P. A. 1972b. Ovarian composition and aspects of the reproductive physiology of Venezuelan white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus gymnotis). Journal of Mammalogy 53: 760-773. BROKX, P. A. 1984. White-tailed deer of South America. Pp. 525-546 in Ecology and Management of the White-Tailed Deer (L.K. Halls, ed.). Stackpole Company, Harrisburg, PA. BROKX, P. A., AND F. M. ANDRESSEN. 1970. Anlisis estomacales del venado caramerudo de los Llanos Venezolanos. Boletin de la Sociedad Venezolana de Ciencias Naturales 28: 330-353. BUENROSTRO SILVA, A. 2005. Segregacin sexual y su relacin con la calidad de la dieta del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus mexicanus) en el Ejido El Limn, Tepalcingo, Morelos. Thesis. Instituto de Ecologa, A.C., Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. CAMARGO-SANABRIA, A. A. 2005. Evaluacin preliminar del rea de accin y patrn de actividad del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus), como parte de una alternativa de manejo ex situ en un bosque seco tropical, (Cundinamarca, Colombia). Thesis. Departamento de Biologa. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogot. CLEMENTE, F. 1984. Utilizacin de la vegetacin nativa en la alimentacin del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus Hays) en el Estado de Aguascalientes. Thesis. Colegio de Postgraduados. Chapingo, Estado de Mxico. Mxico. CALVOPIA-OATE, J. E. 1990. Reintroduccin del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) a Cbano, Puntarenas, Costa Rica. Thesis, Universidad Nacional, Heredia Costa Rica. CALVOPIA-OATE, J. E. 1995. Evaluacin de la reintroduccin del venado cola blanca en Cbano, Puntarenas, Costa Rica. Pp. 369-381 in Ecologa y manejo del venado cola blanca en Mxico y Costa Rica. (C. Vaughan and M. Rodrguez, eds.). EUNA. Heredia, Costa Rica. CONTRERAS, C. 2000. Seleccin de echaderos por el venado cola blanca texano en un matorral xerfilo del Noreste de Mxico. Thesis. Instituto de Ecologa, A.C. Xalapa, Veracruz, Mxico. CONTRERAS-MORENO, F. M. 2008. Ecologa Poblacional del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus thomasi) en la r/a San Joaqun municipio de Balancn, Tabasco, Mxico. Thesis. Universidad Jurez Autnoma de Tabasco, Tabasco, Mxico. CORONA, P. 1999. Patrones de actividad del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus texanus Zimmerman, 1870).Thesis. Facultad de Biologa. Universidad Veracruzana, Mxico.

SECTION 2

114

WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

DI BERNARDINO, D., AND H. HAYES. 1989. International system for cytogenetic nomenclature of domestic animals. ISCNDA. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics 53: 65 79. DI MARE-HERING, M. I. 1991. Hbitos alimentarios de una poblacin insular de venado cola blanca neotropical. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 29: 507. DI MARE, M. I. 1994. Hbitos alimentarios del venado cola blanca en la Isla San Lucas, Puntarenas, Costa Rica. Pp. 6390 in Ecologa y manejo del venado cola blanca en Mxico y Costa Rica. (C. Vaughan and M. Rodrguez, eds.). EUNA. Heredia, Costa Rica. ETTER, A. 1998. Mapa general de ecosistemas de Colombia. Escala 1:1:500.000. Instituto Alexander von Humboltd. Bogot. EZCURRA, E., AND S. GALLINA. 1981. Biology and population dynamics of white-tailed deer in Northwestern Mexico. Pp. 77-108 in Deer biology, habitat requirements and Management in Western North America. (P. F. Ffolliott, and S. Gallina, eds). Instituto de Ecologa, A. C. Mxico, D.F FFOLLIOTT, P. F., AND S. GALLINA (eds). 1981. Deer biology, habitat requirements and Management in Western North America. Instituto de Ecologa, A. C. Mxico, D.F. GALINDO-LEAL, C., and M. WEBER. 1998. El venado de la Sierra Madre Occidental: ecologa, manejo y conservacin. EDICUSA-CONABIO, Mxico. GALLINA, S. 1993a. White-tailed deer and cattle diets at La Michilia, Durango, Mexico. Journal of Range Management 46:487-492. GALLINA, S. 1994a. Dinmica poblacional y manejo de la poblacin del venado cola blanca en la Reserva de de la biosfera La Michila, Durango, Mexico. Pp. 205-245 in Ecologa y manejo del venado cola blanca en Mxico y Costa Rica. (C. Vaughan and M. Rodrguez, eds.). EUNA. Heredia, Costa Rica. GALLINA, S. 1994b. Uso del habitat por el venado cola blanca en la Reserva de de la biosfera La Michila, Mexico. Pp: 299-314 in Ecologa y manejo del venado cola blanca en Mxico y Costa Rica. (C. Vaughan and M. Rodrguez, eds.). EUNA. Heredia, Costa Rica. GALLINA, S., AND J. BELLO. 2000. Comportamiento del venado cola blanca y su hbitat en el Noreste de Mxico. Memorias VII Simposio sobre Venados de Mxico. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. UNAM. 69- 81. GALLINA, S., P. CORONA-ZRATE, AND J. BELLO. 2003. El venado cola blanca: comportamiento en zonas semiridas del Noreste de Mxico. Pp.165-173 in Manejo de Fauna Silvestre en Amazona y Latinoamrica. Seleccin de trabajos V Congreso Internacional. (R. Polanco, ed.). CITES, Fundacin Natura. Bogot. Colombia. GALLINA, S., AND L. A. ESCOBEDO-MORALES. 2009. Anlisis sobre las Unidades de Manejo (UMAs) de ciervo rojo (Cervus elaphus Linnaeus, 1758) y wapiti (Cervus canadensis (Erxleben, 1777) en Mxico: problemtica para la conservacin de los ungulados nativos. Tropical Conser vation Science 2:251-265. Available online: tropicalconservationscience.org.

SECTION 2

CORONA, P. 2003. Bases biolgicas para el aprovechamiento del venado cola blanca en el Ejido El Limn de Cuachichinola, Municipio de Tepalcingo, Morelos. Thesis INECOL, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mxico. CORONEL ARELLANO, H., C. A. LPEZ GONZLEZ, AND C. N. MORENO ARZATE. 2009. Pueden las variables del paisaje predecir la abundancia de venado cola blanca? El caso del noroeste de Mxico. Tropical Conservation Science 2: 229-236. Available online: tropicalconservationscience.org. CORREA-VIANA, M. 1987. Comparacin de cuatro mtodos para la estimacin de la densidad poblacional del venado caramerudo (Odocoileus virginianus gymnotis). Thesis, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela. CORREA-VIANA, M. 1991. Tasa de defecacin del venado caramerudo en Venezuela. Biollania 8: 17-21. CORREA-VIANA, M. 1995. Distribucin y estado actual del venado de pramo en el parque Nacional Sierra nevada, Mrida, Venezuela. 1995. Informe final. Universidad Nacional Experimental de los llanos occidentales Ezequile Zamora. 52 pp. CORREA-VIANA, M. 2000. Movimientos, actividad y uso de hbitat del venados liberados en la finca el Jaimero, Portuguesa, Venezuela. Ph.D. dissertation. Programa integrado de estudios de postgrado en Zoologa agrcola (PIEPZA), Universidad Central de Venezuela, Maracay, Venezuela. CORREAL, U. G., AND T. VAN DER HAMMEN. 1977. Investigaciones Arqueolgicas en los abrigos rocosos del Tequendama: 11.000 aos de prehistoria en la Sabana de Bogot. Biblioteca Banco Popular. Bogot. CUERVO, A., J. HERNANDEZ, AND A. CADENA. 1986. Lista actualizada de los mamferos de Colombia. Anotaciones sobre su distribucin. Caldasia. 15(7175):471-501. DANIELDS, H. 1987. Ecologa nutricional del venado caramerudo (Odocoileus virginianus gymnotis) en los llanos centrales. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Central, Caracas, Venezuela. DANIELDS, H. 1991. Biologa y habitat del venado caramerudo. Pp. 59-66 in El venado en Venezuela: conservacin, manejo, aspectos biolgicos y legales. FUDECI,/PROFAUNA/FEDECAVE, Caracas, Venezuela. DELFIN, C. 2002. Clasificacin y evaluacin del hbitat como primera fase para el establecimiento y operacin de una UMA con fines de aprovechamiento del venado cola blanca mexicano en la Mixteca Poblana. Thesis. Instituto de Ecologa, A.C. Xalapa, Veracruz, Mxico. DELFIN, C., S. MANDUJANO, S. GALLINA, J. BELLO, AND N. LPEZ. 1998. Patrones de desplazamiento del venado cola blanca en un rancho con manejo de agua en el Noreste de Mxico. Memorias VI Simposio sobre Venados de Mxico. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. UNAM. 178-186. DELFIN, C., S. GALLINA, AND C. LOPEZ GONZALEZ. 2009. Evaluacin del habitat del venado cola blanca utilizando modelos espaciales y sus implicaciones para el manejo en el centro de Veracruz, Mxico. Tropical Conservation Science 2: 215-228. Available online: tropicalconservationscience.org.

GALLIANA ET AL. 115

GALLINA, S., AND H. LOPEZ AREVALO. 2008. Odocoileus virginianus. In: IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.1. <www.iucnredlist.org> GALLINA, S., M. E. MAURY, AND V. SERRANO. 1981. Food habits of white-tailed deer. Pp.133-148 in Deer biology, habitat requirements and Management in Western North America (P.F. Ffolliott, and S. Gallina, eds.). Instituto de Ecologa, A. C. Mxico, D.F. GALLINA, S., A. PREZ-ARTEAGA, AND S. MANDUJANO. 1998. Patrones de actividad del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus texanus) en un matorral xerfilo de Mxico. Boletn de la Sociedad Bilogica. Concepcin, Chile (69):221-228. GARCA, L. C., AND R. MONROY. 1985. Estimacin de la poblacin de venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) en la selva caducifolia del sureste del Estado de Morelos. Memorias III Simposio sobre Fauna Silvestre. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. UNAM. 68-80 GEIST, V. 1998. Deer of the World.Their evolution, behavior and ecology. Stackpole Books. USA. GMEZ, G. 1997. Uso de hbitat y tendencia poblacional del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) en una finca ganadera-caera del bosque seco de Costa Rica. Thesis. Conser vacin y Manejo de Vida Silvestre. Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. GMEZ-GIRALDO, C. 2005. Radio-telemetra aplicada a la reintroduccin del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus). Thesis. Bosques y Conservacin Ambiental. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Medelln. GONZLEZ-PREZ, G. E. 2003. Uso del hbitat y rea de actividad del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus sinaloae J. Allen) en la Estacin Cientfica Las Joyas, Reserva de la Biosfera de Manantln, Jalisco. Thesis. Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad Autnoma de Mxico. Mxico, D.F GONZLEZ, A. 2001. Anlisis de la variabilidad fenotpica de una poblacin de Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann, 1780) ante las condiciones ambientales del Parque Nacional Natural El Tuparro, departamento del Vichada, Colombia. Thesis. Departamento de Biologa. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogot. GONZLEZ-MARN, R. M. 2002. Diagnstico de situacin de las Unidades para la conser vacin, Manejo y Aprovechamiento Sustentable de Fauna Silvestre (UMAS), en el Estado de Yucatn, Mxico. Thesis. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. Universidad Autnoma de Yucatn, Mrida, Yucatn. GRANADO, A. 1989. Dieta del venado caramerudo (Odocoileus virginianus gymnotis) en el Socorro, estado Guarico. Thesis, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela. GUZMN, A. R. 2005. Anlisis de las experiencias colombianas de manejo ex situ de venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) como aporte a su conservacin. Thesis. Departamento de Biologa. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogot. HALL, E. R. 1981. The Mammals of North America. 2a. edicin. John Wiley & Sons, New York, E.U.A. 2 vol:6011181 HALLS, L. K. 1978. The White-tailed Deer, Pp. 43-65 in Big game of North America, ecology and management (J.L. Schmidt y D. L. Gilbert, eds.). Wildlife Management Institute. Stackpole Books. Harrisburg. PA. HALLS, L. K. (ed.) 1984. White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA. HERNNDEZCAMACHO, J. E., A. H. HURTADO, R. ORTIZ, AND T. WALSCHBURGER. 1992. Centros de endemismos en Colombia. Pp.175190 in La diversidad Biolgica de Iberoamrica I. G. Halffter (comp.). CYTEDD, Instituto de Ecologa, A.C., Secretara de Desarrollo Social. Mxico. HERNNDEZ-CAMACHO, J., H. SNCHEZ-PAEZ, H. CHIRIVI-GALLEGO, J. MORALES, C. E. BARBOSACASTILLO, G. SNCHEZ, AND J. GIRALDO. 1985. Plan de manejo del Parque Nacional los Nevados. INDERENA, CARDER -CORTOLIMA-CRAMSA & CRQ. Bogot. HERNNDEZ, M. I. 1994. La extensin y la educacin ambiental en el manejo del venado cola blanca en Cubano, provincia Puntarenas, Costa Rica. Pp. 359-368 in Ecologa y manejo del venado cola blanca en Mxico y Costa Rica. (C. Vaughan and M. Rodrguez, eds). EUNA. Heredia, Costa Rica. HESSELTON, W. T., AND R. M. HESSELTON. 1982. Whitetailed deer. Pp. 878-901 in Wild Mammals of North America. (J. A.Chapman and G. A. Feldhame, eds.).The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. HIRTH, D. H. 1977. Social behaviour of white-tailed deer in relation to habitat. Wildlife Monographs 53:1-53. HSU, T., AND K. BENIRSCHKE. 1967. Atlas of mammalian chromosomes. U. S. A. Vol. 3, Folio 43. IUCN. 1994. IUCN Red List Categories. Prepared by the IUCN Species Survival Commission. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. IUCN. 2009. 2009 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.< www.iucnredlist.org> JESUS DE LA CRUZ, A., AND J. BELLO 2004 Estado actual de las poblaciones de venados (Mammalia: Cervidae) en el ejido Oxolotn, Tabasco. Memoria IX simposio de venados en Mxico. FMVZ- UNAM. ANGADI. UAEH Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mxico. KOBELKOWSKY-SOSA, R., AND J. PALACIO-NEZ. 2004. Evaluacin del hbitat y estado poblacional del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus, Hays) en ranchos cinegticos de la Sierra Fria, Aguscalientes. Memorias VIII Simposio sobre Venados de Mxico. UNAM. ANGADI. Huamantla, Tlaxcala, Mxico. 7983 LANDER, E. 1991. El venado caramerudo. Memoria Simposio El Venado en Venezuela: conservacin, manejo, aspectos biolgicos y legales. FUDECI/PROFAUNA/ FEDECAVE, Caracas:133-138 LEN-CASTRO, R. 2000. Criaderos intensivos de venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) en Tabasco: situacin actual y perspectivas. Thesis. Universidad Jurez Autnoma de Tabasco, Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mxico. LEOPOLD, A. S. 1958. Wildlife of Mexico. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. 608 pp.

SECTION 2

116 WHITE-TAILED

DEER

Odocoileus virginianus

forest in Mexico. Ethology Ecology & Evolution 8:255263. MANDUJANO, S., AND S. GALLINA. 2005. Dinmica poblacional del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) en un bosque tropical caducifolio de Jalisco. Pp. 335-348 in Homenaje al Doctor Bernardo Villa. (V. Snchez-Cordero and R. Medelln, eds.). Universidad Nacional Autnoma de Mxico. Mxico, D.F. MANDUJANO, S., S. GALLINA, G. ARCEO, AND L. A. PREZ-JIMNEZ. 2004. Variacin estacional del uso y preferencia de los tipos vegetacionales por el venado cola blanca en un bosque tropical de Jalisco. Acta Zoolgica Mexicana (n.s.) 20(2):45-67. MANDUJANO, S., S. GALLINA, AND S. H. BULLOCK. 1994. Frugivory and dispersal of Spondias purpurea (Anacardiaceae) in a tropical dry forest of Mexico. Revista de Biologa Tropical 42:105-112. MANDUJANO, S., AND A. GONZLEZ-ZAMORA. 2009. Evaluation of natural conservation areas and wildlife management units to support minimum viable populations of white-tailed deer in Mexico. Tropical Conservation Science 2: 237-250. Available online: tropicalconservationscience.org. MANDUJANO, S., A. PREZ-ARTEAGA, R. E. SNCHEZMANTILLA, AND S. GALLINA. 1996. Diferenciacin de pautas de actividad del venado con ayuda de radiotransmisores con sensor de movimiento. Acta Zoolgica Mexicana (n. s.) 67:65-78. MANDUJANO, S., AND V. RICO-GRAY. 1991. Hunting, use, and knowledge of the biology of the white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus (Hays), by the maya of central Yucatan, Mexico. Journal of Ethnobiology 11:175-183. MARCHINTON, R. L., AND D. H. HIRTH. 1984. Behavior. Pp. 129-168 in White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management. (L. K. Halls, ed.). Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA. MARTNEZ-ROMERO, L. E. 2004. Determinacin de fechas de aprovechamiento del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) a travs de hormonas sexuales y comportamiento. Thesis. Instituto de Ecologa, A.C. Xalapa, Veracruz, Mxico. MATEUS-GUTIERREZ, C. 2005, Evaluacin preliminar de la dieta y monitoreo del movimiento del venado cola blanca, Odocoileus virginianus, en semicautiverio en un Bosque seco Tropical (Cundinamarca, Colombia), Thesis. Departamento de Biologa. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogot. MCCOY-COLTON, M. B., AND C.VAUGHANDICKHAUT. 1985. Resultados preliminares del estudio del venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) en Costa Rica. Investigaciones sobre fauna silvestre de Costa Rica. San Jos, Costa Rica. MENDEZ, E. 1984. White-tailed deer populations and habitats of Mexico and Central America. Pp. 513-524 in White-tailed Deer: Ecology and Management. (L.K. Halls, ed.). Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, PA. MENDOZA-CASTILLO, H., AND J. GAMBOAGONZLES. 1993. Establecimiento de un criadero de venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus yucatanensis) en cautiverio. Technical Report. Universidad Autnoma de Chapingo. 33 pp.

SECTION 2