Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know An Evidence Based Approach to Curriculum Development

What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know An Evidence Based Approach to Curriculum Development

Uploaded by

fptintiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know An Evidence Based Approach to Curriculum Development

What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know An Evidence Based Approach to Curriculum Development

Uploaded by

fptintiCopyright:

Available Formats

Health and Social Care Education

ISSN: (Print) 2051-0888 (Online) Journal homepage: www.tandfonline.com/journals/rhep15

What Psychology do Medical Students Need to

Know? An Evidence Based Approach to Curriculum

Development

L. Cordingley, S. Peters, J. Hart, J. Rock, L. Hodges, J. McKendree & C. Bundy

To cite this article: L. Cordingley, S. Peters, J. Hart, J. Rock, L. Hodges, J. McKendree & C. Bundy

(2013) What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know? An Evidence Based Approach

to Curriculum Development, Health and Social Care Education, 2:2, 38-47, DOI: 10.11120/

hsce.2013.00029

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

Published online: 15 Dec 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 8352

View related articles

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rhep15

38

PRACTICE PAPER

What Psychology do Medical Students

Need to Know? An Evidence Based

Approach to Curriculum Development

L. Cordingley1, S. Peters2, J. Hart3, J. Rock4, L. Hodges5, J. McKendree6 & C. Bundy1

1

Dermatological Sciences, Institute for Inflammation and Repair, University of Manchester and Manchester Academic

Health Sciences Centre, Manchester, UK

2

Manchester Centre for Health Psychology, School of Psychological Sciences, University of Manchester and Manchester

Academic Health Sciences Centre, Manchester, UK

3

Manchester Medical School, Manchester Centre for Health Psychology, Manchester, UK

4

Keele Medical School, University of Keele, Keele, UK

5

University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

6

Hull York Medical School, Hull and York, UK

Abstract

While the contribution of behavioural and social

sciences for understanding health, illness and medical

practice is made explicit in documents such as

Tomorrow’s Doctors, research shows that the proportion

of curriculum space given to psychology in

undergraduate curricula varies widely between medical

schools. In the US, recommendations for behavioural

sciences education for medical undergraduates have

been developed. However, the United Kingdom has

yet to produce agreed curriculum outcomes for

behavioural sciences in medical education.

We aimed to develop an evidence-based consensus

behavioural sciences curriculum for undergraduate

medical education. This paper reports a novel

technique for curriculum development that utilises

knowledge and expertise of key stakeholders from

medicine, medical education and behavioural

sciences. It was successfully used to develop a

psychology core curriculum for undergraduate

medicine in the UK.

Keywords: behavioural and social sciences, medical

education, curriculum development

Corresponding author:

Dr Christine Bundy, 6.10 Williamson Building University Background

of Manchester, Oxford Rd, Manchester, M13 7PT, UK

Email: christine.bundy@manchester.ac.uk, Phone: + 44 (0) Social and behavioural factors are important in the

1612 755231 treatment and prevention of almost all the major

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

L. Cordingley et al. 39

diseases and nearly half of preventable deaths can that undergraduate education in the UK was not fit

be linked to behaviours (McGinnis & Foege 1993). for purpose over a decade ago. The result, a set of

Psychological factors such as beliefs and recommendations published as GMC Tomorrow’s

expectations also influence progress in long-term Doctors (1993) signalled a shift in emphasis away

conditions (LTCs) and impact on health outcomes from the learner simply acquiring factually based

and a substantial body of literature has now information to the new graduate being able to

accrued outlining the actual and potential pathways apply the knowledge and skills acquired to medical

between psychological factors and disease end practice. The primary recommendations were to

points (Kawachi et al. 1996, Barefoot et al. 2000, reduce the factual content of programmes,

Andersen 2002, Smith & Ruiz 2002). contextualise the learning and make better use of

modern teaching and learning methods. It was

In addition, the practice of medicine is intellectually,

recommended that the B&SS be included in the

emotionally and behaviourally demanding. Doctors

curriculum on a ‘need to know’ rather than ‘nice to

experience higher levels of divorce, alcoholism and

know’ basis and strongly recommended that more

burnout compared with other professional groups

emphasis be placed on learning to communicate

(Vaillant et al. 1972) and medical practitioners as a

better.

group demonstrate higher levels of stress compared

with other professional groups Firth-Cozens 2003, Further, Tomorrow’s Doctors revisions (GMC 2001,

Taylor et al. 2005) and they tend to be overly self- GMC 2006) reinforce the value of the B&SS in

critical as students, which predicts later distress teaching programmes. Furthermore, psychological

(Firth-Cozens 1992). These are not just problems for principles underpin a range of related topics such

the practitioners themselves and their families, but as patient safety, communication and patient

constitute a quality of care issue, as stressed doctors centredness. In fact, communication skills training

are more prone to making errors (Jones et al. 1988). has been the vehicle for delivery of much of the

B&SS curriculum in undergraduate education.

Despite longstanding arguments for the inclusion of

Behavioural and Social Sciences (B&SS) in medical The current situation in the UK reflects local centres

education (Flexner 1910), the establishment of the of excellence; a small number of departments that

first department of B&SS in a North American have well established expertise. But most medical

medical school in 1959 (Dacey & Weintrob 1973) schools show wide variability in the B&SS curricular

and the incorporation of B&SS in assessment in the content; the teaching delivery methods and the

US in 1976 (Wexler 1976), in the UK systematic learning outcomes are different, assessment

incorporation of B&SS is a relatively recent strategies differ and the B&SS in medical education

occurrence, and attempts to integrate with remain largely invisible other than those

medicine have been met with varying degrees of components embedded in communication training

success (Benbassat et al. 2003). There is as yet no (Russell et al. 2004). In addition, the degree of

dedicated B&SS department in a UK medical school horizontal integration between specialities differs

and no consensus on what should be taught, or between medical schools. Vertical integration

how it should be delivered, when, and by whom. (whether subject teaching spans the whole

programme or is confined to the pre-clinical years)

Developments within UK Medicine is also dependent on the institution. Finally, some

This is not to say that the potential contribution of staff delivering this component are not subject

B&SS equipping medical students with knowledge specialists; some may possess a first degree in a

that will both improve their own effectiveness with related discipline, while others posses a related

patients, and offer protection from ‘burnout’ by allied health qualification only (Russell et al. 2004).

identifying and managing sources of stress, has not Of those who are B&SS discipline experts, many

been acknowledged in the UK. The Royal quickly become dissatisfied and leave because they

Commission on Medical Education (the Todd Report are poorly supported and there is an absence of

1968) and General Medical Council’s (GMC) career development pathways for those in post

Education Committee Working Party on The (Litva & Peters 2008).

Teaching of the Behavioural Sciences, Community Development of learning and teaching

Medicine and General Practice in Basic Medical opportunities are also affected by a variety of

Education report (GMC Education Committee 1987), attitudes and beliefs about B&SS. The conceptual

demonstrate respectively awareness of the need to and theoretical perspectives advanced in B&SS may

improve B&SS teaching for medical undergraduates clash with those dominant in medicine (Jaco 1960),

and progress to the point where virtually every the focus on exploratory and discursive techniques

medical undergraduate curriculum has a well- may be perceived as less useful than those that

developed syllabus in B&SS (most of them emphasise acquisition of facts and practice of skills.

concentrating upon psychology). Further Senior role models may not value or endorse B&SS

developments followed the UK GMC recognition

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

40 What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know?

perspectives and approaches. There may be hostility the depth or level of study specified in a core

to perceived threats to medical autonomy and curriculum for medicine. A final list of 49 separate

perceptions that B&SS lack scientific legitimacy topics were identified in seven areas (Box 1).

(Dacey & Weintrob 1973, Litva & Peters 2008).

They may see it as valuable only as a contribution

to systematic thinking, if it has application as a Box 1 The basic areas of psychology used for the

contributor to, for example psychiatry, or as an Phase 1 topic mapping task

adjunct to development of interpersonal skills

Cognitive (How people remember, think,

relevant to medical consultations (Sheldrake 1973).

Psychology learn, perceive, attend to and

The status of B&SS academics may be perceived to manage information.)

limit their contribution to medical education and

Social (How individuals think and interact

they have been criticised for a lack of attention

Psychology at individual, group and societal

to application of their expert knowledge to levels.)

medicine (Dacey & Weintrob 1973, Bolman 1995,

Developmental (Acquisition and changes in

Benbassat et al. 2003). They may be perceived as Psychology psychological processes from

too critical of medicine and unhelpful to students conception to old age.)

(Tait 1973, Peters & Litva 2006). As a result students

Individual (Factors accounting for differences

become critical and dismissive of B&SS seeing the Differences between individuals, in particular

disciplines as subjective, not amenable to scientific intelligence and personality.)

study, and not having any evidence base other than

Research (Quantitative and qualitative design,

“common sense” (Rees et al. 2002). B&SS may be Methods analysis, ethics, governance and

perceived as nice to know but not need to know measurement.)

populated with concepts that are not familiar and Health and (Psychological processes that

require work if they are to derive the relevance to Clinical contribute to physical and

medical practice (Tait 1973). Psychology mental health and illness.)

Occupational (Psychological processes involved

Need to develop a core curriculum Psychology in performance at work, in

training, how organisations

for the B&SS in Medicine function.)

The GMC recommends that graduates should “…

apply psychological principles, method and

knowledge to medical practice” (GMC Tomorrow’s

Doctors 2009, p15). In this study we focus on Participants were recruited at workshops conducted

defining the relevant aspects of psychology that at two international medical education conferences

medical graduates need to know based on a (one in the US and one in the Netherlands) and

rigorous and inclusive methodology, utilising the worked in six mixed professional groups. At each

model for integrating B&SS developed by US workshop a 15-minute presentation was delivered

medical schools (Cuff & Vanselow 2004). In to orientate participants to the sorting task. It

developing a core curriculum recommendation that covered the GMC’s Good Medical Practice (GMP)

was evidence-based, relevant to clinical practice and framework and the concepts in the BPS Core

acceptable to stakeholders, a novel consultative Curriculum.

methodology was employed.

Individuals formed small mixed professional groups

Method (six to eight participants) and were each given a

set of cards that contained definitions and examples

Three phases of work comprised data collection: of the 49 psychology concepts and an A0 size map

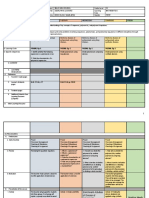

1) topic mapping; 2) topic prioritisation; and 3) data of the GMP categories (Figure 1). To make the

interpretation, integration and validation. sorting task more engaging, the cards were divided

into four ‘suits’ using the familiar playing card

Phase 1: Mapping psychology to medical

symbols: 15 cognitive and developmental

education and practice

psychology topics (clubs); 11 social psychology

Procedure and individual differences topics (spades); 9 Health

and Clinical psychology topics (hearts) and 14

We sampled psychology topics taken from the

Organizational Psychology topics (diamonds).

British Psychological Society (BPS) minimum

syllabus for graduate basis for registration with the Participants were instructed to discuss each topic as

BPS (The British Psychological Society, BPS 2004) it arose from the deck and to place it on the

the BPS syllabus topic areas for postgraduate category of GMP on the map. Blank cards were

qualifications in Health Psychology and Occupational issued if people wanted to place one concept on

Psychology (BPS 2004 a,b). These lists did not imply more than one GMP category. If a concept could

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

L. Cordingley et al. 41

Figure 1 Task mat used in mapping phase

not be placed in any of the seven GMC categories it Phase 2: Topic prioritisation

was recorded as not relevant. Consensus was

Procedure

sought, but if the group could not agree on a

particular concept this was also recorded. A national meeting was arranged for 30 experts

from the newly formed UK Psychology in Medicine

The atmosphere created was congenial and

network, all of whom were currently involved in

encouraged discussion and interaction within the

medical education. Prior to the meeting, the topic

groups with a deliberate attempt to break down

list (Box 1) was sent to delegates. A definition, one

barriers between participants from different

or two indicative key aspects of the topic and

disciplinary/professional backgrounds. Organisers

illustrative examples were provided alongside each

aimed to ensure that participants did not focus on

topic (Figure 2). Apart from the topic that was

defining jargon or become too engrossed with

unanimously viewed as irrelevant in Phase 1, all

detail or disagreement about what the GMP

topics were included. Participants were asked to

categories meant. The aim was to keep participants’

judge whether the topic should be high, medium,

thinking at the level of ‘how could this psychology

low or no priority, or whether it was an area for

topic contribute to good medical practice?’. Each

postgraduate medicine only. The priority levels are

workshop took an hour to complete and the data

shown in Box 2.

on the categories and topics were recorded.

Documents were distributed in advance of the

Results from Phase 1

meeting to ensure they had sufficient time to

Forty-seven participants took part in a workshop. consider the materials and make their priorities.

Of these, thirty-three (57.6%) were medical During the meeting participants were allocated into

practitioners, ten were psychologists (30.3%), three groups of five to six delegates each and asked

and the remaining four stated that they were to discuss the prioritisation task and topics. Each

medical educationalists (12.1%). These formed group recorded on a flipchart the points to emerge

six groups. from the discussion and in turn reported these to

The vast majority of topics were viewed as relevant the group as a whole.

to Good Medical Practice with most cards placed in Results from Phase 2

two or more of the GMP sections. Very few cards

were placed only in one GMC category, with the Detailed findings are provided in Table 1. The topic

majority placed in two or more (range 0–6 from a priorities reported are the modal option for the

possible total of 7). Only one topic was discarded by whole sample. Where no modal option appeared,

participants as not relevant. Specifics of psychology the lower priority was given, thereby giving a

topics mapped to GMP sections are detailed in the conservative view of relevance. Group discussions

core curriculum document (BeSST 2010). during the event were recorded and that data were

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

42 What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know?

Figure 2 Topic layout used in prioritisation response task with example

Topic: D3. Cognitive & Social

Definition: The changes as a function of age and experience during later life.

Aspects of Aging

Indicative Key Points: Examples: Topic Priority

• Normal Ability to differentiate normal changes in cognitive function High Priority

from those caused by disease. Medium Priority

Low Priority

• Relationships over the lifespan Role of social support in illness prevention in old age. Not relevant

Postgrad only

Box 2 Definition of priority levels used in Phase 2

High Priority: Core knowledge – undergraduate medical students should learn basic psychological concepts

and application in medicine.

Medium Priority: Core knowledge – undergraduate medical students should learn how the psychological

concepts involved are applicable to medicine (but not the basic psychological concept).

Low Priority: Useful knowledge but not essential for all UK undergraduate medical programmes.

Postgrad only: Not appropriate for an undergraduate curriculum but should be included in specialist

postgraduate education or training.

Not relevant: Not relevant to medical education or training.

subjected to thematic analysis. The following main scientists, the depth of understanding need

points were identified. not mirror that of graduate psychology

students.

a. Relevance and context. Whilst most viewed the

majority of areas as relevant, all participants c. Gaps in the topic list. Additional core topics

stressed the need to contextualise psychology (identified by at least three participants)

topics by embedding teaching activities within included pain, mental illness, bereavement,

other disciplinary areas and with the patient body image and addiction. The large group

experience. Some concern was expressed that a discussion included substantial debate about

curriculum could simply be seen “as a checklist” the role of psychology in the professional and

and that medical schools would not “think out intellectual development of medics. Thus, as

of the box”. Curriculum integration was seen as well as core knowledge, other aspects of

having particular importance for social and psychology were judged to be crucial to

behavioural sciences. teaching, learning, assessment, and professional

practice.

Additionally, it was recognised that the way the

d. Overlap with other disciplines. Participants

topics were presented needed to reflect the

emphasised the importance of the interfacing of

priorities of medical rather than psychology

psychology with key areas, such as public

curricula. Thus new topic headings that

health, medical sociology, ethics and psychiatry.

highlighted patients’ experiences, doctors’

Topics such as poverty and service delivery

experiences and the learning process were

were viewed as relevant, but as belonging in

elicited, debated and agreed.

the domains of sociology or social policy rather

b. Depth. The group emphasised the need for than psychology, and were therefore omitted.

medical students to have sufficient knowledge

Readers recognised that research methods training

of psychological principles that would allow

was a particularly strong component of

them to apply this knowledge and recognise

undergraduate psychology curricula, but some were

their use of them in practice. However, they

wary of presenting the view that this area is the

were also clear that although as medical

sole remit of ‘psychology’. There was disagreement

practitioners they will be working as applied

as to whether ‘research methods’ was an area that

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

L. Cordingley et al. 43

Table 1 Findings from Phase 2 – Psychology core knowledge with prioritisation levels

1. Psychological factors in health and illness

Topic Priority

Psychological factors in health promotion and illness prevention High

Psychological interventions High

Psychological processes in disease High

Pain High

Genes and behaviour High

Mental health and mental Illness High

2. Psychological responses to illness

Emotional, cognitive and behavioural responses to illness High

Coping with illness High

3. Psychology across the life span

Cognitive development High

Cognitive aspects of ageing High

Social development across the lifespan High

Death, dying and bereavement High

Assessment of cognitive function over the age span Medium

Attachment Medium

4. Cognitive functioning in health and illness

Memory High

Learning High

Sleep and consciousness High

Attention Medium

Perception High

Language High

5. Psychology for professional practice

Clinical reasoning and decision making High

Human communication and communication skills training High

Research methods and evidence based medicine Medium

Social processes shaping professional behaviour High

Stress, well-being and burnout High

Leadership and team-working High

Teaching the next generation of doctors High

should be taught by psychology experts. It was they linked with. We aimed to embed the

decided not to proclaim this area as solely the prioritised aspects of psychology with medical

domain of psychology, but that it would be helpful topics in order demonstrate integration and

for students to be aware of specific areas of learning opportunities in the curricula.

expertise such as assessment of quality of life,

The majority of topics were grouped under the

attitudes and other complex constructs. This would

heading of Psychology – core knowledge, with the

complement other research methods and statistical

remainder as Psychology for professional practice

analyses teaching in epidemiology.

and Psychology – contribution to the educational

Phase 3: Data interpretation, integration process. The detailed output of this phase forms

and validation the curriculum document (BeSST 2010). Table 2

outlines key topic areas under each of these

Topics selected as high priority from Phase 2 were sections. Topics that were identified as more

organised according to which aspects of medicine, suitable for postgraduate level study are included

medical education and professional development in Table 3.

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

44 What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know?

Table 2 Integrated curriculum summary Table 3 Topics identified as post graduate level only

1. Psychology – core knowledge Leadership – The exercise of influence Organisational

1.1 Psychological factors in health and illness over a group or individual to achieve Psychology

certain goals.

1.2 Psychological responses to illness

Selection and Appraisal – The use of Organisational

1.3 Psychology across the life span psychological methods to inform Psychology

1.4 Cognitive functioning in health and illness selection and appraisal processes.

Organisational Change – Managing Organisational

2. Psychology for professional practice change processes. Psychology

2.1 Clinical reasoning and decision making

2.2 Human communication and communication skills

training

2.3 Research methods and evidence-based medicine Discussion

2.4 Social processes shaping professional behaviour This paper describes the application of an expert

2.5 Stress, well-being and burnout consensus technique, an iterative process of

2.6 Leadership and team-working consultation, participation and integration, to the

development of an evidence based core curriculum

2.7 Teaching the next generation of doctors

in behavioural sciences for undergraduate medicine.

3. Psychology – contribution to the educational process Each phase of the process required stakeholders to

3.1 Learning to learn

interrogate aspects of psychology and agree on

how they could be applied to undergraduate

3.2 Skills training

medical education. The result is a curriculum that

3.3 Reflective practice reflects current population health needs as viewed

3.4 Situated learning by medical educators and behavioural and social

3.5 Feedback and appraisal scientists.

3.6 Assessment design and quality assurance A manageable and coherent curriculum, the outline

of which appears in BeSST (2010), can be applied to

4. Psychology topics – Post graduate level only medical undergraduate programmes in the UK. This

4.1 Leadership curriculum has the support of prominent

psychologists, medical educationalists and

4.2 Selection and Appraisal

practitioners and has been endorsed by the BPS

4.3 Organisational Change

and GMC Education committee.

Experts agreed the depth of coverage of particular

areas should be limited to what newly graduating

Validation doctors require. Medical students should not be

Critical readers – all experts in UK medical required to know details of theory development,

programmes and each with at least ten years rather they need to achieve sufficient

involvement with undergraduate medicine delivery understanding of a topic to inform their practice

and all currently professorial appointments – were and decision making at this stage of their career.

asked to read the curriculum and comment on Consideration of a number of issues is crucial in

appropriateness, relevance and structure. They ensuring successful implementation of this core

included heads of UK medical schools, professors curriculum, these include:

of medical education and professors of psychology.

Hidden curriculum. Only by understanding the

The process and content has been endorsed by six barriers to why the B&SS have not been

senior colleagues (see foreword to the core incorporated into medical undergraduate

curriculum in BeSST (2010)), all of the written programmes can any future attempts to implement

comments were positive and stressed the urgency this integrated core curriculum stand a better

for making the recommended curriculum available chance of succeeding. Implicit values are conveyed

for use in designing/re-designing existing to students through the hidden curriculum

programmes. ASME, HEA subject centres and the (Hafferty 1998). It is likely the hidden curriculum

BPS have also endorsed the core curriculum. In undermines the perceived relevance of the B&SS

addition, the core curriculum was referenced in the component of medical undergraduate programmes

latest GMC guidelines to medical schools (GMC and changing that culture may be the biggest

Tomorrow’s Doctors 2009). challenge to B&SS experts in the next decade.

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

L. Cordingley et al. 45

Establishing relevance is crucial, especially in the UK and experience in medical education have

where medical students are younger and may enter provided schools with detailed content and

with less developed understanding of the suggestions for integration and implementation.

psychological aspects of health, illness and medical

2. Better standardisation of the students’

practice. Thus, integrated curricula may have

experiences of teaching and learning about the

greater value to non-graduate entry programmes

psychology contribution to medicine across UK

and overcome some of the attitudinal barriers

medical schools. This encourages medical

towards B&SS in medical curricula. Recent work in

graduates to view psychology as making an

the US has attempted to understand more about

important contribution to their practice, sending

integration (Satterfield et al. 2010). The corollary of

a signal to students that it is core rather than

this, however, is that B&SS experts have to be

optional knowledge for practising medicine.

suitably equipped with a sound understanding of

the practice of medicine and medical education. 3. Providing opportunities for quality control by

internal assurance and external validation

procedures. It would help to build a bank of

Conclusion expertise that could be used to evaluate

This managed process of engaging both medical programmes across the UK.

and psychology experts in a common, focused task 4. Providing opportunities for further development

resulted in consensus of what psychology is of competencies in the B&SS by generating

relevant to undergraduate medicine, and may have interest in developing a forum for sharing best

contributed to the creation of more open and practice and for facilitating research in order to

positive views of psychology in a medical facilitate good medical practice.

curriculum. This process could facilitate the

adoption of a more systematic and evidence-based 5. A core curriculum will support the professional

curriculum for psychology in medical education and identity and develop career pathways of subject

could be used by the other disciplines in medicine experts who may be relatively isolated in

including; medical sociology and healthcare ethics medical schools. This would prevent the loss of

and law. It may have relevance for development of such expertise from medicine to other areas of

B&SS teaching in other healthcare professions. health care.

6. It could facilitate sharing assessment material

Recommendations across universities (for example via the UK

medical schools national assessment

We recommend the adoption of a core curriculum partnership).

for psychology in medicine. A core curriculum in

the UK has the following advantages: 7. Finally, the most important outcome is the

expectation that better knowledge and skill in

1. Supporting medical schools to deliver key the B&SS domains will have an impact on

components of Tomorrow’s Doctors. Medical patient health outcomes.

practitioners and psychologists with expertise

References BeSST (2010) A core curriculum for psychology in

undergraduate medical education. A report from the

Andersen, B.L. (2002) Biobehavioural outcomes Behavioral & Social Sciences Teaching in Medicine

following psychological interventions for cancer (BeSST) Psychology Steering Group. Higher Education

patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Academy. ISBN: 978-1-907207-15-0.

Psychology 70 (3), 590–610.

Boelen, C. (2002) A new paradigm for medical

Barefoot, J., Brummett, B. and Helms, M. (2000) schools a century after Flexner's report. Bulletin of

Depressive symptoms and survival of patients with the World Health Organisation 80 (7), 592–593.

coronary artery disease. Psychosomatic Medicine

62 (6), 790–795. Bolman, W.M. (1995) The place of behavioural

science in medical education and practice. Academic

Benbassat, J., Baumal, R., Borkan, J.M. and Ber, R. Medicine 70 (10), 873–878.

(2003) Overcoming barriers to teaching the

behavioural and social sciences to medical students. Cuff, P. and Vanselow, N. (2004) Improving medical

Academic Medicine 78, 372–380. education: enhancing the behavioral and social

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

46 What Psychology do Medical Students Need to Know?

science content of medical school curricula. Knight, L.V. (2006) A silly expression: consultants’

Washington, DC: National Academies Press. implicit and explicit understanding of Medical

Humanities. A qualitative analysis. Med Humanities

Dacey, A. and Weintrob, J. (1973) Human behaviour:

32 (2), 119–124.

the teaching of social and behavioural sciences in

medical schools. Social Science and Medicine 7 (12), Litva, A. and Peters, S. (2008) Exploring barriers to

943–957. teaching behavioural and social sciences in medical

education. Medical Education 42 (3), 309–314.

Firth-Cozens, J. (1992) The role of early family

experiences in the perception of organizational McGinnis, J. and Foege, W. (1993) Actual causes of

stress: fusing clinical and organizational death in the US. JAMA 270 (18), 2207–2212.

perspectives. Journal of Occupational and

Peters, S. and Litva, A. (2006) Relevant behavioural

Organizational Psychology 65, 61–75.

and social science for medical undergraduates: a

Firth-Cozens, J. (2003) Doctors, their wellbeing, and comparison of specialist and non-specialist

their stress. British Medical Journal 326 (7391), 670–671. educators. Medical Education 40 (10), 1020–1026.

Flexner, A. (1910) Medical education in the United States Rees, C.E., Sheard, C.E. and McPherson, A.C. (2002) A

and Canada. A report to the Carnegie Foundation for the qualitative study to explore undergraduate medical

Advancement of Teaching. Boston, MA: Updyke. students’ attitudes towards communication skills

learning. Med Teach 24 (3), 289–93.

GMC (2001) Good Medical Practice. The Duties of a

Doctor Registered with the GMC. London: General Russell, A., Van Teijlingen, E., Lambert, H. and Stacy, R.

Medical Council. (2004) Social and behavioural science education in

UK medical schools: current practice and future

GMC (2006) Good Medical Practice. The Duties of a

directions. Medical Education 38 (4), 409–417.

Doctor Registered with the GMC. London: General

Medical Council. Satterfield, J.M., Adler, S.R., Chen, H.C., Hauer, K.E.,

Saba, G.W. and Salazar, R. (2010) Creating an ideal

GMC Education Committee (1987) The teaching of

social and behavioural sciences curriculum for medical

behavioural sciences, community medicine and

students. Medical Education 44 (12), 1194–1202.

general practice in basic medical education. London:

General Medical Council. Sheldrake, P. (1973) Behavioural science in the

medical curriculum. Social Science and Medicine

GMC Tomorrow’s Doctors (1993) Recommendations

7 (12), 967–973.

on undergraduate medical education. London:

General Medical Council. Smith, T. and Ruiz, J. (2002), Psychosocial influences

on the development and course of coronary heart

GMC Tomorrow’s Doctors (2003) Recommendations

disease: current status and implications for research

on undergraduate medical education. London:

and practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

General Medical Council.

Psychology 70 (3), 548–568.

GMC Tomorrow’s Doctors (2009) Tomorrow’s

Tait, I. (1973) Behavioural science in medical

Doctors. Outcomes and Standards for Undergraduate

education and clinical practice. Social Science and

Medical Education. London: General Medical Council.

Medicine 7, 1003–1011.

Hafferty, F. (1998) Beyond curriculum reform:

Taylor, C., Graham, J., Potts, H.W.W., Richards, M.A.

confronting medicine's hidden curriculum. Academic

and Ramirez, A.J. (2005) Changes in mental health

Medicine 73 (4), 403–7.

of UK hospital consultants since the mid-1990s. The

Jaco, E.G. (1960) Problems and prospects of the Lancet 366 (9487), 742–744.

social sciences in medical education. Journal of

The British Psychological Society (BPS) (2004)

Health and Human Behavior 1, 29.

Membership and Qualifications Board. Revised Syllabus

Jones, J.W., Barge, B.N., Fay, L.M., Kunz, L.K., for the Qualifying Examination. BPS publications.

Wuebker, L.J. and Steffy, B.D. (1988) Stress and

The British Psychological Society (BPS) (2004a)

medical malpractice: organizational risk assessment

Available at http://www.bps.org.uk/networks-

and intervention. Journal of Applied Psychology

communities/member-networks/divisions/division-

73 (4), 727–735.

health-psychology/division-health-psychology.

Kawachi, I., Colditz, G.A., Ascherio, A., Rimm, E.B.,

The British Psychological Society (BPS) (2004b)

Giovannucci, E., Stampfer, M.J. and Willett, W.C.

Availaible at http://www.bps.org.uk/networks-

(1996) A prospective study of social networks in

communities/member-networks/divisions/division-

relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease

occupational-psychology/division-occupationa.

in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health

50 (3), 245–251.

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

L. Cordingley et al. 47

Vaillant, G., Sobowale, N. and McArthur, C. (1972) Wexler, M. (1976) The behavioural sciences in medical

Some psychological vulnerabilities of physicians. education. American Psychologist 31 (4), 275–283.

New England Journal of Medicine 287, 372–375.

WHO (1970) The social sciences in medical

education. WHO Chronicles 24, 478.

© 2013 S.P. Forrest, HSCE, Vol 2, Issue 2 (October 2013)

The Higher Education Academy doi:10.11120/hsce.2013.00029

You might also like

- LABOR by Poquiz PDFDocument23 pagesLABOR by Poquiz PDFAnonymous 7BpT9OWP100% (3)

- The Renaissance Period in EducationDocument8 pagesThe Renaissance Period in EducationAngelo Ace M. Mañalac0% (1)

- Robert N. Shaffer, MD at 90: An Oral History and MemoirDocument112 pagesRobert N. Shaffer, MD at 90: An Oral History and MemoirGlaucoma Research FoundationNo ratings yet

- Medical Students' Educational Strategies in An Environment of Prestige Hierarchies of Specialties and DiseasesDocument17 pagesMedical Students' Educational Strategies in An Environment of Prestige Hierarchies of Specialties and DiseasesKavirm35No ratings yet

- Evolution of Clinical Reasoning in Dental EducationDocument8 pagesEvolution of Clinical Reasoning in Dental EducationlauraNo ratings yet

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument8 pagesEmotional IntelligenceAnca OPREANo ratings yet

- BrauerDocument12 pagesBrauerNader ElbokleNo ratings yet

- Some of The Best Articles of Our First 10 Years AnDocument6 pagesSome of The Best Articles of Our First 10 Years AnJamilNo ratings yet

- How Medical Education Is ChangingDocument3 pagesHow Medical Education Is ChangingCindy ChiribogaNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Competencies, Educational Goals, and Learning Objectives For Teaching Medical Histology in An Undergraduate Medical Education SettingDocument12 pagesA Guide To Competencies, Educational Goals, and Learning Objectives For Teaching Medical Histology in An Undergraduate Medical Education SettingahmedNo ratings yet

- Defining Clinical Education Parallels in PracticeDocument9 pagesDefining Clinical Education Parallels in Practiceprakritibhatnagar1511No ratings yet

- How Can We Improve Medical EducationDocument9 pagesHow Can We Improve Medical EducationJOMARI MANALONo ratings yet

- Declaración de Consenso Sobre El Contenido de Los Currículos de Razonamiento Clínico en La Educación Médica de Pregrado 2020 INGLESDocument9 pagesDeclaración de Consenso Sobre El Contenido de Los Currículos de Razonamiento Clínico en La Educación Médica de Pregrado 2020 INGLESjaldoquiNo ratings yet

- Depression in Medical Students Current InsightsDocument11 pagesDepression in Medical Students Current InsightsKoas HAYUU 2022No ratings yet

- Community Medicine in Homoeopathy - Way Forward To Reform and InstituteDocument4 pagesCommunity Medicine in Homoeopathy - Way Forward To Reform and InstituteDr JeshNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument8 pagesRetrieveSahian Montserrat Angeles HortaNo ratings yet

- Integration of The Sciences Basic To Medicine... Mennin 2016Document17 pagesIntegration of The Sciences Basic To Medicine... Mennin 2016André OliveiraNo ratings yet

- A Conceptual Framework For Continuing Medical Education and Population HealthDocument16 pagesA Conceptual Framework For Continuing Medical Education and Population HealthDr. MomNo ratings yet

- First Year Doctors Experience of Work Related Wellbeing and Implications For Educational ProvisionDocument7 pagesFirst Year Doctors Experience of Work Related Wellbeing and Implications For Educational ProvisionBhagoo HatheyNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Predictors of Anxiety in Healthcare Professions StudentsDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Predictors of Anxiety in Healthcare Professions StudentsMihaela PanaitNo ratings yet

- Erosion of Empathy in Medical SchoolDocument1 pageErosion of Empathy in Medical SchoolChristian ObandoNo ratings yet

- An Evidence Based Patient Centered Method Makes The Biopsychosocial Model ScientificDocument6 pagesAn Evidence Based Patient Centered Method Makes The Biopsychosocial Model Scientificlumi_vulpitzaNo ratings yet

- Medical Education in The United States. The Role of AndragogyDocument5 pagesMedical Education in The United States. The Role of AndragogydarkbyronsNo ratings yet

- Contuinity of EducationDocument9 pagesContuinity of EducationAngelina CalistaNo ratings yet

- Nursing ResearchDocument15 pagesNursing Researchsubhashreepal13No ratings yet

- Depression and Anxiety Among Medical StudentsDocument6 pagesDepression and Anxiety Among Medical StudentsAlejandro MartinezNo ratings yet

- Geneticsgenomics in Nursing and Health CareDocument15 pagesGeneticsgenomics in Nursing and Health Careapi-215814528No ratings yet

- Philippe Chastonay, Nu Viet Vu, Jean-Paul Humair, Emmanuel Kabengele Mpinga and Laurent BernheimDocument14 pagesPhilippe Chastonay, Nu Viet Vu, Jean-Paul Humair, Emmanuel Kabengele Mpinga and Laurent BernheimtimtimNo ratings yet

- Journal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryDocument8 pagesJournal Homepage: - : Manuscript HistoryIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry in The Medical CurriculumDocument4 pagesBiochemistry in The Medical CurriculumMarites L. DomingoNo ratings yet

- A_New_Teaching_Forum_to_Aid_the_PromotioDocument85 pagesA_New_Teaching_Forum_to_Aid_the_PromotioSGT NEXTNo ratings yet

- Clinical Reasoning What Do Nurses Physicians and Students Reason AboutDocument10 pagesClinical Reasoning What Do Nurses Physicians and Students Reason AboutUmam AcademyNo ratings yet

- Final NaDocument42 pagesFinal NaChastin PeriasNo ratings yet

- Psych 06 00025 v2Document12 pagesPsych 06 00025 v2enrichedenlightenment05No ratings yet

- Mental Health in Medical FacultiesDocument3 pagesMental Health in Medical Facultiestegen79876No ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument11 pagesContent ServerMona AL-FaifiNo ratings yet

- Putting It All Together: Building A Four-Year Curriculum: S. Edwards Dismuke, MD, MSPH, and Alicia M. Mcclary, MS, EddDocument3 pagesPutting It All Together: Building A Four-Year Curriculum: S. Edwards Dismuke, MD, MSPH, and Alicia M. Mcclary, MS, EddtimtimNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Spirituality Into Health Sciences - Schonfeld 2014Document12 pagesIncorporating Spirituality Into Health Sciences - Schonfeld 2014Mércia FiuzaNo ratings yet

- Course Orientation - Preventive Medicine 4 - AY 2021-2022 - SignedDocument24 pagesCourse Orientation - Preventive Medicine 4 - AY 2021-2022 - SignedJolaine ValloNo ratings yet

- Psychological Well-Being in Nursing Students: A Multicentric, Cross-Sectional StudyDocument11 pagesPsychological Well-Being in Nursing Students: A Multicentric, Cross-Sectional StudyLohree Mie HanoyanNo ratings yet

- Yjbm 93 3 433Document7 pagesYjbm 93 3 433daeron42No ratings yet

- Baldassin2008 FDocument8 pagesBaldassin2008 FJr SparkNo ratings yet

- Psychiatry Research: Letter To The EditorDocument2 pagesPsychiatry Research: Letter To The EditorZachNo ratings yet

- Better Together A NaturalistiDocument10 pagesBetter Together A Naturalistinurlaila marasabessyNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion in Medical Education Lessons From A Major Undergraduate Curriculum ImplementationDocument10 pagesHealth Promotion in Medical Education Lessons From A Major Undergraduate Curriculum ImplementationKAREN VANESSA MUÑOZ CHAMORRONo ratings yet

- Module 1 Scholarly Writing Self ReflectionDocument9 pagesModule 1 Scholarly Writing Self Reflectionapi-643329064No ratings yet

- Maintaining Well-Being: A Narrative Review On Burnout Experienced by Medical Students and ResidentsDocument18 pagesMaintaining Well-Being: A Narrative Review On Burnout Experienced by Medical Students and ResidentsClau TomNo ratings yet

- Narrative Review Burnout Students and ResidentsDocument19 pagesNarrative Review Burnout Students and ResidentsStefania TacuNo ratings yet

- Hangbook MBBS Addendum Year3,4,5Document30 pagesHangbook MBBS Addendum Year3,4,5ambreenayub23No ratings yet

- Students' Perception of Medical School Stress and TheirDocument8 pagesStudents' Perception of Medical School Stress and TheirPamela Francisca Bobadilla BurgosNo ratings yet

- Psychological distress among undergraduate medical students the influence of excessive daytime sleepiness and family functioningDocument16 pagesPsychological distress among undergraduate medical students the influence of excessive daytime sleepiness and family functioningsebas paezNo ratings yet

- Medical Student Mental Health 3.0 ImprovingDocument5 pagesMedical Student Mental Health 3.0 Improvingmemmuse95No ratings yet

- Anxiety Among Medical StudentsDocument4 pagesAnxiety Among Medical Studentsvihaan chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Essential QuestionsDocument5 pagesAssignment - Essential QuestionsFionah RetuyaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Global Perspectives of Medical Students On Research During Undergraduate Medical Education A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument14 pagesContemporary Global Perspectives of Medical Students On Research During Undergraduate Medical Education A Systematic Literature Reviewhabihabi0609No ratings yet

- DOT-syllabus 220130 163901Document19 pagesDOT-syllabus 220130 163901Angkasa LamaNo ratings yet

- Articulo PDFDocument9 pagesArticulo PDFNathalie EstephaniaNo ratings yet

- GROUP 1 - Chapter 2 (Revised)Document9 pagesGROUP 1 - Chapter 2 (Revised)itsgumbololNo ratings yet

- School Based Interventions To Improve Health.17Document9 pagesSchool Based Interventions To Improve Health.17lengers poworNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion in Context: A Reflective-Analytical ModelDocument6 pagesHealth Promotion in Context: A Reflective-Analytical Modelmitha letoNo ratings yet

- Mak, 2018. Estilo de Vida Promotor de La Salud y Calidad de Vida Entre Los Estudiantes de Enfermería ChinosDocument8 pagesMak, 2018. Estilo de Vida Promotor de La Salud y Calidad de Vida Entre Los Estudiantes de Enfermería ChinosIván Lázaro IllatopaNo ratings yet

- Shared Goals For Mental Health Research What Why and When For The 2020sDocument10 pagesShared Goals For Mental Health Research What Why and When For The 2020saimeejacobs370No ratings yet

- The Question of Competence: Reconsidering Medical Education in the Twenty-First CenturyFrom EverandThe Question of Competence: Reconsidering Medical Education in the Twenty-First CenturyNo ratings yet

- Reading7th 2 - Ready D Complete and AdptedDocument3 pagesReading7th 2 - Ready D Complete and AdptedRosa Maria Sá RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Foundation Forum: College and Career Center Tops The Priority ListDocument4 pagesFoundation Forum: College and Career Center Tops The Priority ListnsidneyNo ratings yet

- Teaching AptitudeDocument9 pagesTeaching AptitudeSAFA's CreationNo ratings yet

- Fazmeer Rasheed CV (Accountant) FDocument4 pagesFazmeer Rasheed CV (Accountant) FImam HusainNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument22 pagesLesson PlanHarim Qudsi100% (2)

- CAP Knowledge and Skills - IsADocument1 pageCAP Knowledge and Skills - IsAengr_khalid1No ratings yet

- Public Speaking - Reading Material Week 1Document20 pagesPublic Speaking - Reading Material Week 1Linh KhánhNo ratings yet

- Teaching P.E and Health in Elementary Grades: MC PehDocument5 pagesTeaching P.E and Health in Elementary Grades: MC PehIra BerunioNo ratings yet

- My CVDocument2 pagesMy CVapi-546470778No ratings yet

- Daily Lesson LOG: M10AL-Ig-1 M10AL-Ig-1 M10AL-Ig-1 M10AL-Ig-1Document4 pagesDaily Lesson LOG: M10AL-Ig-1 M10AL-Ig-1 M10AL-Ig-1 M10AL-Ig-1ederlynNo ratings yet

- NOTESmtlaws LectureDocument11 pagesNOTESmtlaws LectureCharlemagne GuiribaNo ratings yet

- HAP44 Advanced Manual 10-08-08Document226 pagesHAP44 Advanced Manual 10-08-08chirijas208390% (10)

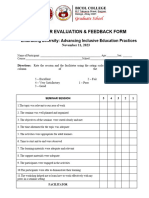

- Seminar Evaluation and Feedback FormDocument2 pagesSeminar Evaluation and Feedback FormMa. Venus A. Carillo100% (2)

- MechanicalDocument16 pagesMechanicalBluesunset1No ratings yet

- ACTIVITY SHEET PR1 WEEK 14 Q4 Finding Answers Through Data CollectionDocument4 pagesACTIVITY SHEET PR1 WEEK 14 Q4 Finding Answers Through Data CollectionAlyssa AngananganNo ratings yet

- Fool Proof MarketingDocument290 pagesFool Proof MarketingKrzysieko0100% (2)

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in Teaching Mathematics VDocument15 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in Teaching Mathematics VKimberly Ann M. AbalosNo ratings yet

- T-TESS Rubric & Documentation: Domain 1.1: Standards and AlignmentDocument17 pagesT-TESS Rubric & Documentation: Domain 1.1: Standards and AlignmentSofia Violeta100% (1)

- Internal Audit ProjectDocument38 pagesInternal Audit ProjectStoryKing100% (1)

- Course Outline in Assessment 1 and Principle 2Document14 pagesCourse Outline in Assessment 1 and Principle 2Benjie Moronia Jr.No ratings yet

- Advanced Scenario 5 - Samantha Rollins (2018)Document10 pagesAdvanced Scenario 5 - Samantha Rollins (2018)Center for Economic Progress0% (1)

- Enrolment Proceedings in GJCSDocument2 pagesEnrolment Proceedings in GJCSDeleter DoraNo ratings yet

- Losoff Haley Resume 2024Document2 pagesLosoff Haley Resume 2024api-736612890No ratings yet

- STID1013 Silibus First Sem 2011Document6 pagesSTID1013 Silibus First Sem 2011Sharifah RubyNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Special Issue The Ethnomusicology of Western Art Music PDFDocument17 pagesIntroduction To The Special Issue The Ethnomusicology of Western Art Music PDFSamuel TanNo ratings yet

- Using ChatGPT and Prompting Like Leonardo Da VinciDocument58 pagesUsing ChatGPT and Prompting Like Leonardo Da VinciKamal A. AL-HumaidiNo ratings yet

- Khalsa College For Women, Civil Lines, Ludhiana: .. Shaping Careers For A Better TomorrowDocument2 pagesKhalsa College For Women, Civil Lines, Ludhiana: .. Shaping Careers For A Better TomorrowPooja ChatleyNo ratings yet