Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eco Theology

Eco Theology

Uploaded by

mertoosCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- BIRD ROSE The Ecological Humanities in Action: An Invitation - AHRDocument7 pagesBIRD ROSE The Ecological Humanities in Action: An Invitation - AHRptqkNo ratings yet

- Incarnational Ministry Planting Churches in Band, Tribal, Peasant, and Urban Societies by Paul G. HiebertEloise Hiebert MenesesDocument454 pagesIncarnational Ministry Planting Churches in Band, Tribal, Peasant, and Urban Societies by Paul G. HiebertEloise Hiebert MenesesBebel Krauss100% (2)

- Burhenn, Herbert. "Ecological Approaches To The Study of Religion." Method & Theory in The Study of ReligionDocument17 pagesBurhenn, Herbert. "Ecological Approaches To The Study of Religion." Method & Theory in The Study of ReligionM SNo ratings yet

- Critical Environmental PhilosophyDocument16 pagesCritical Environmental PhilosophyVasudeva Parayana DasNo ratings yet

- Christocentric Ecotheology and Climate Change: Ezichi A. ItumaDocument5 pagesChristocentric Ecotheology and Climate Change: Ezichi A. ItumaQisthy Corp100% (1)

- Environment EssayDocument26 pagesEnvironment EssayDigby WilkinsonNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Religion and NatureDocument21 pagesEncyclopedia of Religion and NatureDidier G PeñuelaNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Religion and NatureDocument21 pagesEncyclopedia of Religion and NatureMd Abid Hasan Sohag (183012049)No ratings yet

- H. Paul Pantmire, "Ecotheology" inDocument6 pagesH. Paul Pantmire, "Ecotheology" inAnkam ManideepNo ratings yet

- The Eco-Genesis of Ethics and ReligionDocument22 pagesThe Eco-Genesis of Ethics and ReligionJack Dale100% (1)

- Binzon P Thomas - Eco JusticeDocument9 pagesBinzon P Thomas - Eco JusticePhiloBen KoshyNo ratings yet

- Cbo9780511815140a009 PDFDocument15 pagesCbo9780511815140a009 PDFJaden RubinsteinNo ratings yet

- Anthropocentrism and Deep EcologyDocument14 pagesAnthropocentrism and Deep EcologyJiayin SongNo ratings yet

- Dwivedi - Hinduism & EcologyDocument8 pagesDwivedi - Hinduism & EcologyVineet MehtaNo ratings yet

- Science and ReligionDocument5 pagesScience and ReligionVidya auliaNo ratings yet

- DWIVEDI VedicHeritageEnvironmental 1997Document13 pagesDWIVEDI VedicHeritageEnvironmental 1997Sanjeev BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Science and ReligionDocument5 pagesScience and ReligionCharmaine WongNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Environmental EthicsDocument6 pagesDissertation Environmental EthicsPaperWritingCompanyEugene100% (1)

- Ecology Its Relative Importance and Absolute Irrelevance For A Christian A Kierkegaardian Transversal Space For The Controversy On Eco TheologyDocument9 pagesEcology Its Relative Importance and Absolute Irrelevance For A Christian A Kierkegaardian Transversal Space For The Controversy On Eco TheologyTroy CabrillasNo ratings yet

- Why Is Environmental Science Called An Interdisciplinary Field of Study?Document4 pagesWhy Is Environmental Science Called An Interdisciplinary Field of Study?Daniel AnayaNo ratings yet

- Buddhism and The Ecocrisis: HE Role OF Uddhism IN Enhancingenvironmental Philosophy AND Psychology IN THE West TodayDocument10 pagesBuddhism and The Ecocrisis: HE Role OF Uddhism IN Enhancingenvironmental Philosophy AND Psychology IN THE West TodayopNo ratings yet

- ECO - Justice and An Emergent Missiological AspectDocument10 pagesECO - Justice and An Emergent Missiological AspectIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Ecology and Tasawwuf: Shahidan Radiman School of Applied Physics Faculty of Science and Technology UKM E-MailDocument81 pagesEcology and Tasawwuf: Shahidan Radiman School of Applied Physics Faculty of Science and Technology UKM E-MailMuh AbdillahNo ratings yet

- What Is Environnmental Ethics?Document34 pagesWhat Is Environnmental Ethics?Maaz Mulla100% (1)

- ExploringDocument6 pagesExploringAlexa AguilosNo ratings yet

- Religious TraditionsandBiodiversityDocument9 pagesReligious TraditionsandBiodiversityKriti ShivagundeNo ratings yet

- Week Eleven Lecture TwoDocument9 pagesWeek Eleven Lecture TwoAlaa ShaathNo ratings yet

- ECO LIT-Green PoliticsDocument37 pagesECO LIT-Green PoliticsManoj KanthNo ratings yet

- How 'Deep' Is Deep EcologyDocument6 pagesHow 'Deep' Is Deep EcologyRobert Maurice TobíasNo ratings yet

- Ronie Zoe HawkinsDocument41 pagesRonie Zoe HawkinsKamaljot ਕੌਰNo ratings yet

- Environmental EthicsDocument3 pagesEnvironmental EthicsRandom TvNo ratings yet

- 11 Chapter 4Document36 pages11 Chapter 4Maninderjit Singh KhattraNo ratings yet

- Meditations On Systems Thinking, Spiritual Systems, and Deep EcologyDocument13 pagesMeditations On Systems Thinking, Spiritual Systems, and Deep EcologyjohnkalespiNo ratings yet

- Rerc2 048 1Document14 pagesRerc2 048 1viginimary1990No ratings yet

- Moltmann Speaking at The Eco-Environmentalists Conference: Ecology and Theology in DialogueDocument16 pagesMoltmann Speaking at The Eco-Environmentalists Conference: Ecology and Theology in DialogueAdrian Jr.No ratings yet

- Beyond The Nature-Culture DualismDocument23 pagesBeyond The Nature-Culture DualismVasudeva Parayana DasNo ratings yet

- EcologyDocument4 pagesEcologyDuan GonmeiNo ratings yet

- Review of FieldDocument5 pagesReview of FieldRohith KumarNo ratings yet

- Dalton e Simmons. Ecotheology and The Practice of Hope PDFDocument201 pagesDalton e Simmons. Ecotheology and The Practice of Hope PDFAugusto MeirellesNo ratings yet

- Eco-Lit FinalDocument31 pagesEco-Lit FinalLoida Manongsong100% (1)

- Connecting With Ecological FuturesDocument14 pagesConnecting With Ecological FuturesGeovanni3618No ratings yet

- Ecological Space The Concept and Its Eth PDFDocument15 pagesEcological Space The Concept and Its Eth PDFVu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Environmentalism of The Poor and The Political Ecology of Prophecy A Contribution To Liberation EcotheologyDocument185 pagesEnvironmentalism of The Poor and The Political Ecology of Prophecy A Contribution To Liberation EcotheologyNoor Alifa Ardianingrum100% (1)

- Proceedings 3 2012 Fjeld A Christian Ecological Ethics With Special Reference To Human Stewardship of God S Creation PDFDocument19 pagesProceedings 3 2012 Fjeld A Christian Ecological Ethics With Special Reference To Human Stewardship of God S Creation PDFMikee RamosNo ratings yet

- Ethics and The Environment: Prepared by Group 8Document20 pagesEthics and The Environment: Prepared by Group 8Iam AbdiwaliNo ratings yet

- Thesis Deep EcologyDocument6 pagesThesis Deep Ecologydwk3zwbx100% (2)

- Taoism and EcologyDocument22 pagesTaoism and Ecologysorbciren10No ratings yet

- Environmental Ethics - SoebirkDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Ethics - SoebirkVarundeep SinghNo ratings yet

- CFP Irti Conference 2022Document3 pagesCFP Irti Conference 2022bruryesNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chepter 2Document46 pages07 - Chepter 2Shalini DhalNo ratings yet

- The Earth and Its SacrednessDocument7 pagesThe Earth and Its Sacrednesschapter2008100% (1)

- Université de GenèveDocument10 pagesUniversité de GenèveVladimer TsitlidzeNo ratings yet

- Gregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunDocument12 pagesGregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunsankofakanianNo ratings yet

- Environmental EthicsDocument6 pagesEnvironmental EthicsgamecielNo ratings yet

- Anthropocentrism: Ecocentrism in Environmental EthicsDocument5 pagesAnthropocentrism: Ecocentrism in Environmental EthicsLawrence TumaponNo ratings yet

- Wendy Ambrosius On Deep EcologyDocument8 pagesWendy Ambrosius On Deep EcologyVidushi ThapliyalNo ratings yet

- BROWN TOADVINE. Eco-Phenomenology - Back To The Earth Itself - First Pages PDFDocument16 pagesBROWN TOADVINE. Eco-Phenomenology - Back To The Earth Itself - First Pages PDFSócrates FranciscanusNo ratings yet

- Deep EcologyDocument9 pagesDeep EcologyMithra BilhanaManivannanNo ratings yet

- Exegesis of Psalm 131Document18 pagesExegesis of Psalm 131mertoosNo ratings yet

- NT Exegesis 3-6 ChaptersDocument8 pagesNT Exegesis 3-6 ChaptersmertoosNo ratings yet

- Ecological Theology(Laudato Si & Laudate Deum) Pope FrancisDocument11 pagesEcological Theology(Laudato Si & Laudate Deum) Pope FrancismertoosNo ratings yet

- How Can We Learn What Veritatis Splendor Has to TeachDocument6 pagesHow Can We Learn What Veritatis Splendor Has to TeachmertoosNo ratings yet

- Holy God We Praise Thy NameDocument1 pageHoly God We Praise Thy NamemertoosNo ratings yet

- Verbum in Ecclesia Part 2 of Verbum DominiDocument13 pagesVerbum in Ecclesia Part 2 of Verbum DominimertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord A Sat np1Document4 pagesDivine Ord A Sat np1mertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord Fri EpDocument38 pagesDivine Ord Fri EpmertoosNo ratings yet

- Justice in 4 Social Documents of ChurchDocument12 pagesJustice in 4 Social Documents of ChurchmertoosNo ratings yet

- Theology of The SacramentsDocument11 pagesTheology of The SacramentsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord e Thu NPDocument3 pagesDivine Ord e Thu NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Review of Luke Timothy Johnson S ProphetDocument8 pagesReview of Luke Timothy Johnson S ProphetmertoosNo ratings yet

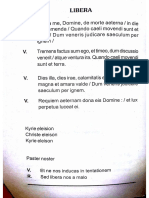

- Libera MeDocument3 pagesLibera MemertoosNo ratings yet

- Ps. 22 An Exegesis in MalayalamDocument4 pagesPs. 22 An Exegesis in MalayalammertoosNo ratings yet

- Ps 51 An Exegesis in MalayalamDocument2 pagesPs 51 An Exegesis in MalayalammertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord B Mon NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord B Mon NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- I'm My Own BookDocument1 pageI'm My Own BookmertoosNo ratings yet

- July 21 ReadingsDocument3 pagesJuly 21 ReadingsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord F Fri NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord F Fri NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord A Sun np2Document4 pagesDivine Ord A Sun np2mertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord C Tue NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord C Tue NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Antigen Test Request FormDocument2 pagesAntigen Test Request FormmertoosNo ratings yet

- Recollection For MeditationDocument5 pagesRecollection For MeditationmertoosNo ratings yet

- My First Book of Spanish Words by Kudela, Katy RDocument33 pagesMy First Book of Spanish Words by Kudela, Katy Rmertoos50% (2)

- Android Search Telegram ChannelsDocument4 pagesAndroid Search Telegram ChannelsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Eucharist ReadingsDocument9 pagesEucharist ReadingsmertoosNo ratings yet

- The Kerala Panchayat Raj (Burial and Burning Grounds) Rules, 1998Document7 pagesThe Kerala Panchayat Raj (Burial and Burning Grounds) Rules, 1998mertoosNo ratings yet

- MCQ BRFWDocument37 pagesMCQ BRFWmertoosNo ratings yet

- Veg@Lent 2023Document2 pagesVeg@Lent 2023mertoosNo ratings yet

- Principles of Growth and DevelopmentDocument2 pagesPrinciples of Growth and DevelopmentMerlin AlfaneNo ratings yet

- Store Name: United Food Company Kaust: It Code DescriptionDocument20 pagesStore Name: United Food Company Kaust: It Code DescriptionFazlul RifazNo ratings yet

- Goetic Spells by SkipDocument3 pagesGoetic Spells by SkipPhil DanielsNo ratings yet

- Lê Thị Thu Thuỷ - Luận vănDocument97 pagesLê Thị Thu Thuỷ - Luận vănĐào Nguyễn Duy TùngNo ratings yet

- 2022421593543深圳大学成人高等教育本科生学士学位英语水平考试样卷Document9 pages2022421593543深圳大学成人高等教育本科生学士学位英语水平考试样卷nova yiNo ratings yet

- Automated Guided VehicleDocument14 pagesAutomated Guided VehicleSRI RAMNo ratings yet

- Marketing Rule BookDocument20 pagesMarketing Rule BookAnn Holman75% (4)

- Colonialism and Imperialism by Usman KhanDocument2 pagesColonialism and Imperialism by Usman KhanUSMANNo ratings yet

- Adhd Add Individualized Education Program GuideDocument40 pagesAdhd Add Individualized Education Program Guidelogan0% (1)

- Kitex Annual Report - WEB View - 2017-18Document160 pagesKitex Annual Report - WEB View - 2017-18ashokvardhnNo ratings yet

- Lucies Farm Data Protection ComplaintDocument186 pagesLucies Farm Data Protection ComplaintcraigwalshNo ratings yet

- VentreCanard Trail of A Single Tear Gazellian Series 3Document367 pagesVentreCanard Trail of A Single Tear Gazellian Series 3Lost And Wander100% (1)

- TL-WN722N (UN) (US) V2 Datasheet PDFDocument4 pagesTL-WN722N (UN) (US) V2 Datasheet PDFBender :DNo ratings yet

- Combichem: Centrifugal PumpsDocument8 pagesCombichem: Centrifugal PumpsrizkyNo ratings yet

- Group2 Non Executive ResultsDocument3 pagesGroup2 Non Executive ResultsGottimukkala MuralikrishnaNo ratings yet

- Green AlgaeDocument3 pagesGreen AlgaeGladys CardonaNo ratings yet

- MATH CHALLENGE GRADE 2 - Google FormsDocument5 pagesMATH CHALLENGE GRADE 2 - Google FormsAivy YlananNo ratings yet

- TJC History 2021 BrochureDocument27 pagesTJC History 2021 BrochureMelissa TeoNo ratings yet

- What A Body Can DoDocument26 pagesWhat A Body Can DoMariana Romero Bello100% (1)

- Nec 2018Document33 pagesNec 2018Abraham AnaelyNo ratings yet

- Wastestation Compact: Transport SavingDocument2 pagesWastestation Compact: Transport Savingaamogh.salesNo ratings yet

- In The District of Columbia Court of Appeals: Applicant, VDocument26 pagesIn The District of Columbia Court of Appeals: Applicant, VMartin AustermuhleNo ratings yet

- Kapandji TrunkDocument245 pagesKapandji TrunkVTZIOTZIAS90% (10)

- 1 Cyber Law PDFDocument2 pages1 Cyber Law PDFKRISHNA VIDHUSHANo ratings yet

- Market Analysis On Tata IndicaDocument47 pagesMarket Analysis On Tata Indicasnehasis nandyNo ratings yet

- Hemanth PHP Resume-1Document3 pagesHemanth PHP Resume-1hemanthjinnala777No ratings yet

- Before Reading: An Encyclopedia EntryDocument6 pagesBefore Reading: An Encyclopedia EntryĐào Nguyễn Duy TùngNo ratings yet

- LSM MockDocument5 pagesLSM MockKazi Rafsan NoorNo ratings yet

- Hispanic Tradition in Philippine ArtsDocument14 pagesHispanic Tradition in Philippine ArtsRoger Pascual Cuaresma100% (1)

- Ruq Abdominal PainDocument55 pagesRuq Abdominal PainriphqaNo ratings yet

Eco Theology

Eco Theology

Uploaded by

mertoosCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eco Theology

Eco Theology

Uploaded by

mertoosCopyright:

Available Formats

WHAT IS ECO-THEOLOGY?

Author(s): Lawrence Troster

Source: CrossCurrents , DECEMBER 2013, Vol. 63, No. 4, TOWARD AN ECO-THEOLOGY

(DECEMBER 2013), pp. 380-385

Published by: Wiley

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24462307

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wiley is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to CrossCurrents

This content downloaded from

178.238.172.188 on Thu, 30 Sep 2021 14:11:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WHAT IS ECO-THEOLOGY?

Lawrence Troster

Ill hen I first began to be active in the religious environmental mo

III ment over twenty-five years ago, I was often invited to be part

UU interfaith panel discussions to discuss how religious traditio

viewed the environment. On these panels there was usually found a P

estant, a Catholic (Christians always seemed to get two seats), myself

resenting Judaism, a Muslim and sometimes a Buddhist and a Hindu

Each of us would, of course, say that our religions were "green" an

quote a few teachings from our sacred texts. After all, who would w

to say in a public forum that our traditions were not "green"? My o

involvement with religious environmentalism had developed out of m

theological interest in the science and religion dialogue and from my

sonal concern about climate change. After having participating in a n

ber of these dialogues, I realized that what we were all saying was

essentially nonsense.

How could ancient faith communities, based on pre-modern sacred

texts, be "green," when the modern environmental crisis was unprece

dented in kind and in scale from any previous human encounter with

the natural world? While Judaism, for example, has traditional sources

that are concerned with consumption, local pollution and water conserva

tion,1 it would be beyond my ancestors' comprehension to understand cli

mate change, species extinction and toxic pollution. Thus traditional

religions cannot be "green," for two important reasons. First of all, there

is a qualitative difference between modern and pre-modern technology

and how it affects the environment in both spatial and temporal terms.

Secondly, and more importantly, over the last several hundred years,

380 -CROSSCURRENTS © 2013 Association for Religion and Intellectual Life

This content downloaded from

178.238.172.188 on Thu, 30 Sep 2021 14:11:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LAWRENCE TROSTER

scientific knowledge of the natural world has deve

thus creating a worldview that is radically differe

ancestors. For example, the development of evoluti

discovery of the genetic code have collapsed the "sacr

Abrahamic faiths which saw an ontological divide

the rest of fife. This new scientific understanding

into question one of the most fundamental doctrin

that humans are created "in the image of God," an

heart of these communities' ethical systems.2 Ther

nities could truly be "green," and traditional sources

evant to developing a modern religious perspective

crisis.

I was seeing in these interfaith panels what Cath

Haught called the "apologetic" religious response to

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when environm

becoming a widespread popular movement, there w

tional religions that claimed that they were one of

humanity's destructive exploitation of the natural

Christian and Jewish theologians countered both t

this attack, but also tried to show how their tradition

that could be in conformity with the modern env

Haught characterizes it, this approach argues, "if o

timeless religious virtues we could alleviate the cri

fives to be shaped by genuinely Christian virtues,

would have the appropriate balance, and we could a

looms before us."5

In this "apologetic" reading of Judaism and Chr

tions as they already existed could be completely ad

to the environmental crisis. In Judaism, for examp

halakhic (legal) texts were held up to show that the

already as "green" as it needed to be and that Jud

mental ethic that long ago anticipated the modern

ment. The apologetic response usually ends up esp

ethic in which humanity and its needs are still the ce

religious communities still adhere to this kind of

own reflections of how faith traditions have respond

the most important crisis facing humanity since

DECEMBER 2013 · 381

This content downloaded from

178.238.172.188 on Thu, 30 Sep 2021 14:11:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WHAT IS ECO-THEOLOGY?

nuclear weapons, it is completely inadequate and

effect on how those communities have actually

dig deeper.

Haught saw in 1993 the beginning of what he

approach" to the environmental crisis. The sac

porates the modern scientific knowledge of the

mos itself as the primary text of revelation. It

communities must recast their theologies abou

Creation in response to this new worldview. Th

become known as eco-theology.

My own first encounter with eco-theology w

iy's Dream of the Earth.6 Berry's theology changed

on how religions should respond to the environ

influenced my own theological work to this day

eco-theologian and I have written numerous art

traditional Jewish theological concepts of divine

tion and Redemption, into an eco-theology perspec

Even though there are numerous exponents of

no clear definition of what it is. H. Paul Santmire, one of the first Chris

tian eco-theologians, defines eco-theology as describing the "theological

discourse that highlights the whole 'household' of God's creation, espe

cially the world of nature, as an interrelated system (eco is from the Greek

word for household, oikos)."7 Jay McDaniel, on the other hand, sees eco

theology not as a theological approach but a "web-of-life movement inso

far as it takes the well-being of life as a whole—rather than ever-increas

ing economic growth—as the central organizing principle of its social

vision."8 He sees the process thought of Alfred North Whitehead as the

philosophical foundation of the eco-theology movement which he under

stands as an orientation toward fife as opposed to consumerism and

fundamentalism.

I have come to understand eco-theology as the integration of the new

scientific perspective on the natural world with traditional theological

concepts, producing a new theological paradigm. My own theological

work was in part inspired by the realization that Moses Maimonides

(1135-1204) did this very thing in his own theology: incorporating the

best "science" of his day within traditional Jewish theological categories.

Eco-theology has, I believe, the potential to go beyond an apologetic

382 · CROSSCURRENTS

This content downloaded from

178.238.172.188 on Thu, 30 Sep 2021 14:11:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LAWRENCE TROSTER

religious environmentalism and generate a more effective ethical

response to the environmental crisis.

In attempting to better define eco-theology, here are some of its pos

sible characteristics:

1. Eco-theology proceeds first and foremost from the new scientific per

spectives of the natural world that have developed over the last several

centuries. This new knowledge, especially from the sciences of cosmology,

biology, genetics, ecology and evolution, has radically altered our under

standing of the human relationship to the natural world. This science has

also produced a technology whose reach in power and ability to trans

form the natural world is unprecedented in human histoiy. This science

has also made us realize the extent and danger of environmental crisis.

2. Eco-theology usually includes some form of personal story. It often is

expressed through a deep sense of place (eco-location) and the personal

history of one's own relationship to the natural world (eco-autobiography).9

3. Eco-theology has been profoundly influenced by eco-feminism. Eco

feminism asserts that the development of the environmental crisis was

an inevitable part of the historical exploitation of women.10 Many of the

most important eco-theologians are also eco-feminists11 who have recast

their conceptions of God and who have rejected the many dualisms

(mind/body; spirit/matter; human/animal, etc.) that lie at the heart of

much of traditional theology and philosophy. Eco-feminism also chal

lenges the idea that all scientific endeavors are value-free and forces us to

see how this false assumption has had an impact on the development of

technology and public policy decisions.12

4. Eco-theology uses several methods to transform traditional religion. As

formulated by Maiy Evelyn Tucker13 these are:

a. Retrieval: finding previously neglected or ignored material within

traditional sources that may speak to a modern eco-theological per

spective. For example, the Book of Job in the Hebrew Bible contains a

view of the human relationship to Creation that approaches a bio-cen

trist position that is very much in opposition to more anthropocentric

sources such as Genesis 1. In rabbinic literature, Job was reinterpreted

to almost completely exclude this very radical view.14

b. Reinterpretation: Eco-theology reinterprets traditional sacred texts,

liturgy and rituals within an ecological context. For example, in

DECEMBER 2013 · 383

This content downloaded from

178.238.172.188 on Thu, 30 Sep 2021 14:11:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WHAT IS ECO-THEOLOGY?

Judaism, the minor observance of the New Year

vat) has become the Jewish Earth Day in many

the environmental rernterpretation and recasti

tury mystical seder.15

c. Reconstruction: Eco-theology can radically re

theology to reflect a more "planetary expressio

mentioned above, Creation is the primaiy text of

lation of the new "story" of Creation from the

have an impact on the way we spiritually respond

and change what we mean by "revelation." From

revelation (which is more universalistic than most

our idea of God must change from a supernatural

of Becoming who knows the universe temporal

seen not a supernatural event from outside of the

ral process in which God is self-revealing through

a Jewish perspective, this changes the role of God

a teacher, exercising power not by coercion, but o

In 2007, the Reverend Fletcher Harper and I cr

Fellowship Program. It is a programmatic response t

lack of formal religious environmental leadershi

ship Program is an educational and training prog

and ordained religious leaders into religious envi

program is designed to educate leaders from dive

able to respond to environmental issues within in

munities.

A central aspect of the Fellowship Program is to have the participants

create their own eco-theologies. They are asked to do this after a

three-day retreat devoted to the spiritual and theological dimension of

environmentalism. These personal eco-theologies are meant to be the

basis of a personal voice from which the graduates of the Program can

speak to their own communities. These statements usually include an

eco-autobiography and an analysis of traditional sacred sources.

What follows in this issue of Crosscurrents are five eco-theologies, the

original versions of which were written for the GreenFaith Fellowship

Program. Each is unique to the life and perspective of the writer, but all

share many of the same characteristics of what constitutes eco-theology.

CROSSCURRENTS

This content downloaded from

178.238.172.188 on Thu, 30 Sep 2021 14:11:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

LAWRENCE TROSTER

There are now over 100 GreenFaith Fellows from t

Muslim and Hindu communities and they have be

cant impact on the religious environmental move

into practice the transformation of their tradition

challenge of eco-theology.

Notes

1. A good summary of these ideas can be found in David Ehrenfeld and Phillip J. Bentley,

"Judaism and the Practice of Stewardship," in: Martin D. Yaffe, Judaism and Environmental Eth

ics: A Reader (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books: 2001), p. 125-135.

2. See: Lawrence Troster, "The Order of Creation and the Emerging God: Evolution and

Divine Action in the Natural World," in: Geoffrey Cantor & Marc Swetlitz editors, Jewish Tra

dition and the Challenge of Darwinism, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), p. 225-246.

3. John F. Haught, The Promise of Nature: Ecology, and Cosmic Purpose (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock

Publishers, 1993), p. 90f.

4. See Yaffe, Judaism and Environmental Ethics, p. 6-8.

5. Haught, The Promise of Nature, p. 91-2.

6. Thomas Berry, The Dream of the Earth (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1988).

7. From "Ecotheology" in: Encyclopedia of Science and Religion, editors Wentzel Van Huyssteen,

Niels Henrik Gregersen, Nancy R. Howell, Wesley J. Wildman, 2003.

8. Jay McDaniel, "Ecotheology and World Religions," in: Laurel Kearns & Catherine Keller,

editors, Ecospirit: Religions and Philosophies for the Earth (New York: Fordham University Press,

2007), pp. 22, 26.

9. Eco-location and eco-autobiography are central features of all environmental education.

See: Mitchell Thomashow, Ecological Identity: Becoming a Reflective Environmentalist (Cambridge:

MIT Press, 1996).

10. See for example: Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific

Revolution (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1980).

11. See for example the work of Sallie McFague, Rosemary Radford Ruether, and Catherine

Keller.

12. See for example the work of Vandana Shiva.

13. Mary Evelyn Tucker, Worldly Wonder: Religions Enter Their Ecological Phase (Chicago: Open

Court, 2003), p. 36f.

14. For example see my blog post, "Four Biblical Voices on our Relationship to Creation"

(http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rabbi-lawrence-troster/biblical-voices-on-creation_b_859549.

html) and also: William P. Brown, The Seven Pillars of Creation: The Bible, Science, and the Ecology

of Wonder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

15. The modern Tu B'Shevat seder was created by Ellen Bernstein, the founder of the first

Jewish environmental organization Shomrei Adamah. She utilized a kabbalistic seder and

rewrote it within an environmental context. Versions of this seder have become the most

utilized forms of this ritual.

16. Lawrence Troster, "The Book of Black Fire: An Eco-Theology of Revelation," Conservative

Judaism 62:1, 2010, p. 132-151.

DECEMBER 2013 · 385

This content downloaded from

178.238.172.188 on Thu, 30 Sep 2021 14:11:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- BIRD ROSE The Ecological Humanities in Action: An Invitation - AHRDocument7 pagesBIRD ROSE The Ecological Humanities in Action: An Invitation - AHRptqkNo ratings yet

- Incarnational Ministry Planting Churches in Band, Tribal, Peasant, and Urban Societies by Paul G. HiebertEloise Hiebert MenesesDocument454 pagesIncarnational Ministry Planting Churches in Band, Tribal, Peasant, and Urban Societies by Paul G. HiebertEloise Hiebert MenesesBebel Krauss100% (2)

- Burhenn, Herbert. "Ecological Approaches To The Study of Religion." Method & Theory in The Study of ReligionDocument17 pagesBurhenn, Herbert. "Ecological Approaches To The Study of Religion." Method & Theory in The Study of ReligionM SNo ratings yet

- Critical Environmental PhilosophyDocument16 pagesCritical Environmental PhilosophyVasudeva Parayana DasNo ratings yet

- Christocentric Ecotheology and Climate Change: Ezichi A. ItumaDocument5 pagesChristocentric Ecotheology and Climate Change: Ezichi A. ItumaQisthy Corp100% (1)

- Environment EssayDocument26 pagesEnvironment EssayDigby WilkinsonNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Religion and NatureDocument21 pagesEncyclopedia of Religion and NatureDidier G PeñuelaNo ratings yet

- Encyclopedia of Religion and NatureDocument21 pagesEncyclopedia of Religion and NatureMd Abid Hasan Sohag (183012049)No ratings yet

- H. Paul Pantmire, "Ecotheology" inDocument6 pagesH. Paul Pantmire, "Ecotheology" inAnkam ManideepNo ratings yet

- The Eco-Genesis of Ethics and ReligionDocument22 pagesThe Eco-Genesis of Ethics and ReligionJack Dale100% (1)

- Binzon P Thomas - Eco JusticeDocument9 pagesBinzon P Thomas - Eco JusticePhiloBen KoshyNo ratings yet

- Cbo9780511815140a009 PDFDocument15 pagesCbo9780511815140a009 PDFJaden RubinsteinNo ratings yet

- Anthropocentrism and Deep EcologyDocument14 pagesAnthropocentrism and Deep EcologyJiayin SongNo ratings yet

- Dwivedi - Hinduism & EcologyDocument8 pagesDwivedi - Hinduism & EcologyVineet MehtaNo ratings yet

- Science and ReligionDocument5 pagesScience and ReligionVidya auliaNo ratings yet

- DWIVEDI VedicHeritageEnvironmental 1997Document13 pagesDWIVEDI VedicHeritageEnvironmental 1997Sanjeev BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Science and ReligionDocument5 pagesScience and ReligionCharmaine WongNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Environmental EthicsDocument6 pagesDissertation Environmental EthicsPaperWritingCompanyEugene100% (1)

- Ecology Its Relative Importance and Absolute Irrelevance For A Christian A Kierkegaardian Transversal Space For The Controversy On Eco TheologyDocument9 pagesEcology Its Relative Importance and Absolute Irrelevance For A Christian A Kierkegaardian Transversal Space For The Controversy On Eco TheologyTroy CabrillasNo ratings yet

- Why Is Environmental Science Called An Interdisciplinary Field of Study?Document4 pagesWhy Is Environmental Science Called An Interdisciplinary Field of Study?Daniel AnayaNo ratings yet

- Buddhism and The Ecocrisis: HE Role OF Uddhism IN Enhancingenvironmental Philosophy AND Psychology IN THE West TodayDocument10 pagesBuddhism and The Ecocrisis: HE Role OF Uddhism IN Enhancingenvironmental Philosophy AND Psychology IN THE West TodayopNo ratings yet

- ECO - Justice and An Emergent Missiological AspectDocument10 pagesECO - Justice and An Emergent Missiological AspectIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Ecology and Tasawwuf: Shahidan Radiman School of Applied Physics Faculty of Science and Technology UKM E-MailDocument81 pagesEcology and Tasawwuf: Shahidan Radiman School of Applied Physics Faculty of Science and Technology UKM E-MailMuh AbdillahNo ratings yet

- What Is Environnmental Ethics?Document34 pagesWhat Is Environnmental Ethics?Maaz Mulla100% (1)

- ExploringDocument6 pagesExploringAlexa AguilosNo ratings yet

- Religious TraditionsandBiodiversityDocument9 pagesReligious TraditionsandBiodiversityKriti ShivagundeNo ratings yet

- Week Eleven Lecture TwoDocument9 pagesWeek Eleven Lecture TwoAlaa ShaathNo ratings yet

- ECO LIT-Green PoliticsDocument37 pagesECO LIT-Green PoliticsManoj KanthNo ratings yet

- How 'Deep' Is Deep EcologyDocument6 pagesHow 'Deep' Is Deep EcologyRobert Maurice TobíasNo ratings yet

- Ronie Zoe HawkinsDocument41 pagesRonie Zoe HawkinsKamaljot ਕੌਰNo ratings yet

- Environmental EthicsDocument3 pagesEnvironmental EthicsRandom TvNo ratings yet

- 11 Chapter 4Document36 pages11 Chapter 4Maninderjit Singh KhattraNo ratings yet

- Meditations On Systems Thinking, Spiritual Systems, and Deep EcologyDocument13 pagesMeditations On Systems Thinking, Spiritual Systems, and Deep EcologyjohnkalespiNo ratings yet

- Rerc2 048 1Document14 pagesRerc2 048 1viginimary1990No ratings yet

- Moltmann Speaking at The Eco-Environmentalists Conference: Ecology and Theology in DialogueDocument16 pagesMoltmann Speaking at The Eco-Environmentalists Conference: Ecology and Theology in DialogueAdrian Jr.No ratings yet

- Beyond The Nature-Culture DualismDocument23 pagesBeyond The Nature-Culture DualismVasudeva Parayana DasNo ratings yet

- EcologyDocument4 pagesEcologyDuan GonmeiNo ratings yet

- Review of FieldDocument5 pagesReview of FieldRohith KumarNo ratings yet

- Dalton e Simmons. Ecotheology and The Practice of Hope PDFDocument201 pagesDalton e Simmons. Ecotheology and The Practice of Hope PDFAugusto MeirellesNo ratings yet

- Eco-Lit FinalDocument31 pagesEco-Lit FinalLoida Manongsong100% (1)

- Connecting With Ecological FuturesDocument14 pagesConnecting With Ecological FuturesGeovanni3618No ratings yet

- Ecological Space The Concept and Its Eth PDFDocument15 pagesEcological Space The Concept and Its Eth PDFVu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Environmentalism of The Poor and The Political Ecology of Prophecy A Contribution To Liberation EcotheologyDocument185 pagesEnvironmentalism of The Poor and The Political Ecology of Prophecy A Contribution To Liberation EcotheologyNoor Alifa Ardianingrum100% (1)

- Proceedings 3 2012 Fjeld A Christian Ecological Ethics With Special Reference To Human Stewardship of God S Creation PDFDocument19 pagesProceedings 3 2012 Fjeld A Christian Ecological Ethics With Special Reference To Human Stewardship of God S Creation PDFMikee RamosNo ratings yet

- Ethics and The Environment: Prepared by Group 8Document20 pagesEthics and The Environment: Prepared by Group 8Iam AbdiwaliNo ratings yet

- Thesis Deep EcologyDocument6 pagesThesis Deep Ecologydwk3zwbx100% (2)

- Taoism and EcologyDocument22 pagesTaoism and Ecologysorbciren10No ratings yet

- Environmental Ethics - SoebirkDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Ethics - SoebirkVarundeep SinghNo ratings yet

- CFP Irti Conference 2022Document3 pagesCFP Irti Conference 2022bruryesNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chepter 2Document46 pages07 - Chepter 2Shalini DhalNo ratings yet

- The Earth and Its SacrednessDocument7 pagesThe Earth and Its Sacrednesschapter2008100% (1)

- Université de GenèveDocument10 pagesUniversité de GenèveVladimer TsitlidzeNo ratings yet

- Gregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunDocument12 pagesGregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunsankofakanianNo ratings yet

- Environmental EthicsDocument6 pagesEnvironmental EthicsgamecielNo ratings yet

- Anthropocentrism: Ecocentrism in Environmental EthicsDocument5 pagesAnthropocentrism: Ecocentrism in Environmental EthicsLawrence TumaponNo ratings yet

- Wendy Ambrosius On Deep EcologyDocument8 pagesWendy Ambrosius On Deep EcologyVidushi ThapliyalNo ratings yet

- BROWN TOADVINE. Eco-Phenomenology - Back To The Earth Itself - First Pages PDFDocument16 pagesBROWN TOADVINE. Eco-Phenomenology - Back To The Earth Itself - First Pages PDFSócrates FranciscanusNo ratings yet

- Deep EcologyDocument9 pagesDeep EcologyMithra BilhanaManivannanNo ratings yet

- Exegesis of Psalm 131Document18 pagesExegesis of Psalm 131mertoosNo ratings yet

- NT Exegesis 3-6 ChaptersDocument8 pagesNT Exegesis 3-6 ChaptersmertoosNo ratings yet

- Ecological Theology(Laudato Si & Laudate Deum) Pope FrancisDocument11 pagesEcological Theology(Laudato Si & Laudate Deum) Pope FrancismertoosNo ratings yet

- How Can We Learn What Veritatis Splendor Has to TeachDocument6 pagesHow Can We Learn What Veritatis Splendor Has to TeachmertoosNo ratings yet

- Holy God We Praise Thy NameDocument1 pageHoly God We Praise Thy NamemertoosNo ratings yet

- Verbum in Ecclesia Part 2 of Verbum DominiDocument13 pagesVerbum in Ecclesia Part 2 of Verbum DominimertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord A Sat np1Document4 pagesDivine Ord A Sat np1mertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord Fri EpDocument38 pagesDivine Ord Fri EpmertoosNo ratings yet

- Justice in 4 Social Documents of ChurchDocument12 pagesJustice in 4 Social Documents of ChurchmertoosNo ratings yet

- Theology of The SacramentsDocument11 pagesTheology of The SacramentsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord e Thu NPDocument3 pagesDivine Ord e Thu NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Review of Luke Timothy Johnson S ProphetDocument8 pagesReview of Luke Timothy Johnson S ProphetmertoosNo ratings yet

- Libera MeDocument3 pagesLibera MemertoosNo ratings yet

- Ps. 22 An Exegesis in MalayalamDocument4 pagesPs. 22 An Exegesis in MalayalammertoosNo ratings yet

- Ps 51 An Exegesis in MalayalamDocument2 pagesPs 51 An Exegesis in MalayalammertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord B Mon NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord B Mon NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- I'm My Own BookDocument1 pageI'm My Own BookmertoosNo ratings yet

- July 21 ReadingsDocument3 pagesJuly 21 ReadingsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord F Fri NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord F Fri NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord A Sun np2Document4 pagesDivine Ord A Sun np2mertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord C Tue NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord C Tue NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Antigen Test Request FormDocument2 pagesAntigen Test Request FormmertoosNo ratings yet

- Recollection For MeditationDocument5 pagesRecollection For MeditationmertoosNo ratings yet

- My First Book of Spanish Words by Kudela, Katy RDocument33 pagesMy First Book of Spanish Words by Kudela, Katy Rmertoos50% (2)

- Android Search Telegram ChannelsDocument4 pagesAndroid Search Telegram ChannelsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Eucharist ReadingsDocument9 pagesEucharist ReadingsmertoosNo ratings yet

- The Kerala Panchayat Raj (Burial and Burning Grounds) Rules, 1998Document7 pagesThe Kerala Panchayat Raj (Burial and Burning Grounds) Rules, 1998mertoosNo ratings yet

- MCQ BRFWDocument37 pagesMCQ BRFWmertoosNo ratings yet

- Veg@Lent 2023Document2 pagesVeg@Lent 2023mertoosNo ratings yet

- Principles of Growth and DevelopmentDocument2 pagesPrinciples of Growth and DevelopmentMerlin AlfaneNo ratings yet

- Store Name: United Food Company Kaust: It Code DescriptionDocument20 pagesStore Name: United Food Company Kaust: It Code DescriptionFazlul RifazNo ratings yet

- Goetic Spells by SkipDocument3 pagesGoetic Spells by SkipPhil DanielsNo ratings yet

- Lê Thị Thu Thuỷ - Luận vănDocument97 pagesLê Thị Thu Thuỷ - Luận vănĐào Nguyễn Duy TùngNo ratings yet

- 2022421593543深圳大学成人高等教育本科生学士学位英语水平考试样卷Document9 pages2022421593543深圳大学成人高等教育本科生学士学位英语水平考试样卷nova yiNo ratings yet

- Automated Guided VehicleDocument14 pagesAutomated Guided VehicleSRI RAMNo ratings yet

- Marketing Rule BookDocument20 pagesMarketing Rule BookAnn Holman75% (4)

- Colonialism and Imperialism by Usman KhanDocument2 pagesColonialism and Imperialism by Usman KhanUSMANNo ratings yet

- Adhd Add Individualized Education Program GuideDocument40 pagesAdhd Add Individualized Education Program Guidelogan0% (1)

- Kitex Annual Report - WEB View - 2017-18Document160 pagesKitex Annual Report - WEB View - 2017-18ashokvardhnNo ratings yet

- Lucies Farm Data Protection ComplaintDocument186 pagesLucies Farm Data Protection ComplaintcraigwalshNo ratings yet

- VentreCanard Trail of A Single Tear Gazellian Series 3Document367 pagesVentreCanard Trail of A Single Tear Gazellian Series 3Lost And Wander100% (1)

- TL-WN722N (UN) (US) V2 Datasheet PDFDocument4 pagesTL-WN722N (UN) (US) V2 Datasheet PDFBender :DNo ratings yet

- Combichem: Centrifugal PumpsDocument8 pagesCombichem: Centrifugal PumpsrizkyNo ratings yet

- Group2 Non Executive ResultsDocument3 pagesGroup2 Non Executive ResultsGottimukkala MuralikrishnaNo ratings yet

- Green AlgaeDocument3 pagesGreen AlgaeGladys CardonaNo ratings yet

- MATH CHALLENGE GRADE 2 - Google FormsDocument5 pagesMATH CHALLENGE GRADE 2 - Google FormsAivy YlananNo ratings yet

- TJC History 2021 BrochureDocument27 pagesTJC History 2021 BrochureMelissa TeoNo ratings yet

- What A Body Can DoDocument26 pagesWhat A Body Can DoMariana Romero Bello100% (1)

- Nec 2018Document33 pagesNec 2018Abraham AnaelyNo ratings yet

- Wastestation Compact: Transport SavingDocument2 pagesWastestation Compact: Transport Savingaamogh.salesNo ratings yet

- In The District of Columbia Court of Appeals: Applicant, VDocument26 pagesIn The District of Columbia Court of Appeals: Applicant, VMartin AustermuhleNo ratings yet

- Kapandji TrunkDocument245 pagesKapandji TrunkVTZIOTZIAS90% (10)

- 1 Cyber Law PDFDocument2 pages1 Cyber Law PDFKRISHNA VIDHUSHANo ratings yet

- Market Analysis On Tata IndicaDocument47 pagesMarket Analysis On Tata Indicasnehasis nandyNo ratings yet

- Hemanth PHP Resume-1Document3 pagesHemanth PHP Resume-1hemanthjinnala777No ratings yet

- Before Reading: An Encyclopedia EntryDocument6 pagesBefore Reading: An Encyclopedia EntryĐào Nguyễn Duy TùngNo ratings yet

- LSM MockDocument5 pagesLSM MockKazi Rafsan NoorNo ratings yet

- Hispanic Tradition in Philippine ArtsDocument14 pagesHispanic Tradition in Philippine ArtsRoger Pascual Cuaresma100% (1)

- Ruq Abdominal PainDocument55 pagesRuq Abdominal PainriphqaNo ratings yet