Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reverb Basics

Reverb Basics

Uploaded by

simonballemusicCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- MPM TroubleshootingDocument34 pagesMPM TroubleshootingMustafaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Least Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Document14 pagesLeast Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Renge Taña91% (33)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Diatonic Harmony 1Document1 pageDiatonic Harmony 1simonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Unit 4 Composition Written Account TemplateDocument5 pagesUnit 4 Composition Written Account TemplatesimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Development of Technology-Based Music 1 - Synths & MIDIDocument6 pagesThe Development of Technology-Based Music 1 - Synths & MIDIsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The History of CompressionDocument4 pagesThe History of Compressionsimonballemusic100% (2)

- As Music Tech. Logbook 2011 TemplateDocument11 pagesAs Music Tech. Logbook 2011 TemplatesimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- As Trial Recording Task GenericDocument2 pagesAs Trial Recording Task GenericsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- As Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Document20 pagesAs Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Hannah Louise Groarke-YoungNo ratings yet

- A2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Document12 pagesA2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Hannah Louise Groarke-YoungNo ratings yet

- Drum and Bass RevisionDocument3 pagesDrum and Bass Revisionsimonballemusic100% (1)

- As Trial Recording Task GenericDocument2 pagesAs Trial Recording Task GenericsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- July IV 2012 Concert FinalDocument1 pageJuly IV 2012 Concert FinalsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Music Department Work PlanDocument6 pagesMusic Department Work PlansimonballemusicNo ratings yet

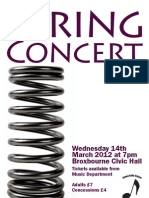

- Spring 2012 ConcertDocument2 pagesSpring 2012 ConcertsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Tips From A Mastering EngineerDocument2 pagesTips From A Mastering EngineersimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The 1980s: New WaveDocument7 pagesThe 1980s: New WavequartalistNo ratings yet

- Diatonic Melody FragmentsDocument1 pageDiatonic Melody FragmentssimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Late 1960s: You Can Do What You Want ToDocument4 pagesThe Late 1960s: You Can Do What You Want TosimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Intro MidiDocument16 pagesIntro Midiwizard_of_keysNo ratings yet

- A Revolution in Pop Music - 1960sDocument3 pagesA Revolution in Pop Music - 1960ssimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Concert Details For ParentsDocument7 pagesConcert Details For ParentssimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Distribution FormatsDocument2 pagesDistribution Formatsmws_97No ratings yet

- History of RecordingDocument6 pagesHistory of RecordingMatt Gooch0% (1)

- Rock and RollDocument3 pagesRock and RollsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Development of Technology-Based Music 3 - InstrumentsDocument5 pagesThe Development of Technology-Based Music 3 - Instrumentssimonballemusic100% (1)

- Indercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDocument294 pagesIndercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDr Sneha's Skin and Allergy Clinic IndiaNo ratings yet

- Case Study of A Condemned Boiler & Methods To Re-Establish ItDocument43 pagesCase Study of A Condemned Boiler & Methods To Re-Establish Its sivaNo ratings yet

- Government of Karnataka: Only For Birth Verification PurposeDocument1 pageGovernment of Karnataka: Only For Birth Verification PurposeAmit VantagodiNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument7 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- ANALE - Stiinte Economice - Vol 2 - 2014 - FinalDocument250 pagesANALE - Stiinte Economice - Vol 2 - 2014 - FinalmhldcnNo ratings yet

- Design and Synthesis of Zinc (Ii) Complexes With Schiff Base Derived From 6-Aminopenicillanic Acid and Heterocyclic AldehydesDocument6 pagesDesign and Synthesis of Zinc (Ii) Complexes With Schiff Base Derived From 6-Aminopenicillanic Acid and Heterocyclic AldehydesIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Answer KeyDocument21 pagesAnswer KeyJunem S. Beli-otNo ratings yet

- Lf-74 Wire Feeder: Operator's ManualDocument50 pagesLf-74 Wire Feeder: Operator's ManualLuis Eduardo Cesena De La VegaNo ratings yet

- Term Paper (Dev - Econ-2)Document14 pagesTerm Paper (Dev - Econ-2)acharya.arpan08No ratings yet

- Metals and Non Metals NotesDocument3 pagesMetals and Non Metals NotesVUDATHU SHASHIK MEHERNo ratings yet

- Performance Evaluation of Selected Ceramic Companies of BangladeshDocument14 pagesPerformance Evaluation of Selected Ceramic Companies of BangladeshmotaazizNo ratings yet

- Deed of DonationDocument2 pagesDeed of DonationMary RockwellNo ratings yet

- AUDCISE Unit 3 Worksheets Agner, Jam Althea ODocument3 pagesAUDCISE Unit 3 Worksheets Agner, Jam Althea OdfsdNo ratings yet

- Question Bank FormatDocument5 pagesQuestion Bank Formatmahidpr18No ratings yet

- The Entrepreneurial and Entrepreneurial Mind: Week #2Document20 pagesThe Entrepreneurial and Entrepreneurial Mind: Week #2Mr.BaiGNo ratings yet

- The Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeDocument6 pagesThe Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeVikram Singh ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Appeals Composition and TranslationDocument54 pagesRhetorical Appeals Composition and Translationteacher briculNo ratings yet

- UNIT 3 Part 1-Propositional LogicDocument11 pagesUNIT 3 Part 1-Propositional LogicVanshika ChauhanNo ratings yet

- If ملخص قواعدDocument2 pagesIf ملخص قواعدAhmed GaninyNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 04 - Lecture Mod PDFDocument72 pagesChapter - 04 - Lecture Mod PDFtahirNo ratings yet

- User Manual of CUBOIDDocument50 pagesUser Manual of CUBOIDshahinur rahmanNo ratings yet

- The Law of ParkinsonDocument5 pagesThe Law of Parkinsonathanassiadis2890No ratings yet

- Ethnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesDocument13 pagesEthnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesJeff Bryan Arellano HimorNo ratings yet

- SB KarbonDocument3 pagesSB KarbonAbdul KarimNo ratings yet

- Study Session8Document1 pageStudy Session8MOSESNo ratings yet

- Project Summary, WOFDocument2 pagesProject Summary, WOFEsha GargNo ratings yet

- Usb MSC Boot 1.0Document19 pagesUsb MSC Boot 1.0T.h. JeongNo ratings yet

- Veterinary MicrobiologyDocument206 pagesVeterinary MicrobiologyHomosapienNo ratings yet

Reverb Basics

Reverb Basics

Uploaded by

simonballemusicOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reverb Basics

Reverb Basics

Uploaded by

simonballemusicCopyright:

Available Formats

Music Technology Reverb Reverb

Sounds bounce off the surfaces of any space, or off objects within a space, repeatedly, gradually dying out until they are inaudible. The bouncing soundwaves result in a reflection pattern, more commonly known as a reverberation (or reverb). The early part of a reverb consists of a number of discrete reflections that you can clearly discern before the diffuse reverb tail builds up. These early reflections are essential to how you perceive the space of a room. All information about the size and shape of a room that the human ear can discern is contained in these early reflections. As a rule, a wider early-reflection spacing is interpreted by the brain as a larger space. The first form of reverb used in music production was actually a special room with hard surfaces (called an echo chamber). It was used to add echoes to the signal. Mechanical devices, including plates and springs, were used to add reverberation to the output of musical instruments and microphones. Digital recording introduced digital reverb effects, which consist of thousands of delays of varying lengths and intensities.

Music Technology Reverb

Reverb in Practice

Artificial reverb is an integral part of music production, as it puts back the sense of space and place that's removed by close-miking voices and instruments in an acoustically dead studio. The reverb type and its settings need to be chosen carefully if the human hearing system is to accept it as natural or at least believable. On the most fundamental level, both delay and reverb are about adding the characteristics of an acoustic environment, either by creating simple echoes or by simulating more complex patterns of sonic reflections. The reason these effects are usually so important at mixdown is because the individual parts in most modern multitrack projects communicate very little in the way of a common sense of space, and as such sound a bit 'dislocated', rather than seeming to belong on the same record. Obviously, synthesizers and sampled sounds often have no sense of acoustic realism to

Music Technology Reverb

them at all, but even miked instruments are often recorded very close up to reduce room reflections as much as possible. This means decisions about the nature of the production's overall acoustic space can be deferred until the final mixdown. For this reason, the primary objective of reverbs and delays is to reconnect tracks that have no inherent connection by giving them some shared acoustic characteristics.

Music Technology Reverb

Setting Reverb Time and Level

Too long a reverb time means you can't fade it up far enough without washing out the whole mix. If reverb time is too short its difficult to get a full sound without sending your tracks too far back in the mix.

Almost every reverb processor has some kind of control to change the length of the reverb (often labelled Decay Time or Reverb Time), so one of the most important things you can do is to experiment with different reverb length settings, juggling the return channel's fader in tandem, to find the best balance between these two parameters. You will need to come back to this late in the mix, as it can be difficult to judge properly until the comparative reverb levels for all the instruments are set up.

Setting Pre Delay

The time between the original signal and the arrival of the early reflections can be adjusted by a parameter commonly known as pre delay.

In a real room, this would equate to how long the sound takes to reach the first surface and then bounce back to the listener. The longer the pre-delay, the larger the space feels. Modern digital reverbs do the same by offering adjustable pre-delay times. For

Music Technology Reverb

a decay time of 1.2 seconds or so and a pre-delay of 60-80ms.

example, a typical vocal reverb treatment might comprise a plate reverb emulation with

In practice, too short a Predelay tends to make it difficult to pinpoint the position of the signal. It can also colour the sound of the original signal. On the other hand, too long a Predelay can be perceived as an unnatural echo. It can also divorce the original signal from its early reflections, which leaves an audible gap. The optimum Predelay setting depends on the type (or envelope) of signal. Percussive signals generally require shorter predelays than signals where the attack fades in gradually. A good practice is to use the longest Predelay possible before you start to hear undesirable side effects, such as an audible echo.

If youre going for a natural-sounding, harmonic reverb, the transition between the early reflections and the reverb tail should be as smooth and seamless as possible. Set the Initial Delay so that it is as long as possible, without a noticeable gap between the early reflections and the reverb tail.

Music Technology Reverb

Music Technology Reverb

Reverb Tips

Because rock and pop music tends to be recorded in fairly dead acoustic spaces, it is nearly always necessary to add artificial reverb, but today's styles use a lot less obvious reverb than those of a couple of decades ago.

Using too much reverb or too long a setting smothers the timbral and rhythmic subtleties of individual parts, and can cause vibrant mixes to become flat and distant.

This is a subjective decision, though, so if you don't have the confidence to decide what works best, go back to commercial mixes in the same genre, and try to hear what kind of reverb they've used.

As a rule, don't add reverb to bass sounds or kick drums, with the possible exception of very short ambience treatments you'll soon find your mixes disappearing into the mud if you overdo it, and many mix engineers avoid reverb on low instruments altogether.

Don't let the reverb fill in all the spaces in your mix, because the spaces are every bit as important as the notes that surround them.

Music Technology Reverb

Reverb needs to suit the music it is applied to slowly unfolding New Age music might be fine with lots of long rich reverb, but that same effects use is unlikely to suit most fast-paced rhythmic music.

Remember that reverb can help to create front-back perspective in your mix, so don't apply it with a trowel unless you want your mix to lose its sense of contrast and depth.

Stereo pad sounds probably don't need much reverb they often have lots already and, in any case, are already designed to fill gaps in an arrangement, so adding extra reverb usually verges on overkill.

Large amounts of long reverb are also less than suitable for most basses and low drums One factor always to keep in mind when mixing is that a heavy application of reverb tends to make a sound appear to be more distant, and that's often at odds with the concept of a lead vocal that you want to keep upfront. Shorter, brighter reverbs feel closer, while warmer, longer reverbs push sounds to the back. If you need more obvious reverb on a lead vocal, then keeping it bright and adding some pre-delay is one way to prevent the sound being pushed too far back.

Music Technology Reverb

Today's drum sounds are drier and tighter than the roomy sounds of the '70s and '80s, so a focus on early reflections tends to be very effective in producing the desired sound and sense of space without the result getting messy. For a more traditional rock drum sound, though, a synthesized reverb plate still sounds fantastic.

It is not uncommon to filter out some low end from a reverb to prevent it clouding that vulnerable low-mid range.

Another basic principle when looking for reverbs that will bind a mix together is to tread carefully with any that seem to have very prominent frequency extremes. Neither very high frequencies nor very low frequencies are much use when using reverb to bind a track together, the former tending to make the reverb too audible in its own right, and the latter reducing punch at the low end of the mix where definition is normally really important.

A useful rule of thumb is to set the reverb level where you think it needs to be, then just back it off another 3 or 4 dB or so.

Music Technology Reverb

10

Music Technology Reverb

Extract from Sound on Sound article by Mike Senior Published in July 2008

11

On the face of it, if you're trying to get your tracks to sound as though they're all roughly in the same space, sending to a single global reverb from all of them is a common-sense approach. However, in my experience this puts a lot more pressure on the engineer to select and tweak that single reverb to get respectable results, so I usually suggest to those starting out that it's actually easier if they use two. Let me explain how this works. The idea is that the two reverbs each serve different purposes, and they can be mixed and matched to cope with a range of recording types within most typical projects. The first reverb is short (usually well under a second in length) and with perhaps only 5-10ms of pre-delay. What this does is simply make disconnected sounds stick together more convincingly within the mix, as well as setting the distance between these sounds and the listener, but without making itself obviously audible as an added effect, given its minimal reverb 'tail'. (As a result, some engineers call this effect ambience rather than reverb.) The second reverb can then be set to give much more of a sense of an acoustic space, using a longer and perhaps slightly brighter reverb as required, but combining that with a fairly long pre-delay (maybe 30-70ms), to avoid the effect distancing sounds that it's applied to very much further.

Having these two reverbs on hand, you can then deal with a variety of different situations. For example, a bone-dry synthesizer track that belongs in the track's background might need lots of

Music Technology Reverb

12

short reverb to push it away from the listener, whereas a lead vocal might only have just enough to make it sound as if it belongs in the mix indeed, it might have none at all if you want to achieve the most upfront sound, albeit at the risk of it sounding disconnected from the record as a whole. Both of the tracks may need a bit of the longer reverb, though, if you're trying to make them sound natural together. To take another example, drum overhead mics that already have a lot of room sound on them could easily warrant no added reverb at all (although you might try to match the sound of the longer reverb to them somewhat, to get other, drier sounds to work alongside), but some of the accompanying close mics may benefit from some of the shorter variety, to avoid them advancing too far forward in the mix perspective. A retriggered drum sample, however, would probably need both reverbs, carefully applied, to blend it convincingly with the rest of the kit: the shorter reverb would primarily set its distance, while the longer could help to retrospectively teleport it into the original recording room. Clearly, both of your reverbs will need to be tweaked to suit the track, but as long as you stay focused on their respective purposes you shouldn't go too far wrong. If the shorter reverb can't blend tracks together before it becomes too audible, try further reducing its reverb time or dial in some EQ cuts on the reverb return channel. If the longer reverb is making things sound distant, you can take off some high end to push it further into the background; if it's making things sound woolly, adjust that level/length ratio or crank up the return channel's high-pass filter.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- MPM TroubleshootingDocument34 pagesMPM TroubleshootingMustafaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Least Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Document14 pagesLeast Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Renge Taña91% (33)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Diatonic Harmony 1Document1 pageDiatonic Harmony 1simonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Unit 4 Composition Written Account TemplateDocument5 pagesUnit 4 Composition Written Account TemplatesimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Development of Technology-Based Music 1 - Synths & MIDIDocument6 pagesThe Development of Technology-Based Music 1 - Synths & MIDIsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The History of CompressionDocument4 pagesThe History of Compressionsimonballemusic100% (2)

- As Music Tech. Logbook 2011 TemplateDocument11 pagesAs Music Tech. Logbook 2011 TemplatesimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- As Trial Recording Task GenericDocument2 pagesAs Trial Recording Task GenericsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- As Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Document20 pagesAs Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Hannah Louise Groarke-YoungNo ratings yet

- A2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Document12 pagesA2 Music Tech Brief 2012 2013Hannah Louise Groarke-YoungNo ratings yet

- Drum and Bass RevisionDocument3 pagesDrum and Bass Revisionsimonballemusic100% (1)

- As Trial Recording Task GenericDocument2 pagesAs Trial Recording Task GenericsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- July IV 2012 Concert FinalDocument1 pageJuly IV 2012 Concert FinalsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Music Department Work PlanDocument6 pagesMusic Department Work PlansimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Spring 2012 ConcertDocument2 pagesSpring 2012 ConcertsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Tips From A Mastering EngineerDocument2 pagesTips From A Mastering EngineersimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The 1980s: New WaveDocument7 pagesThe 1980s: New WavequartalistNo ratings yet

- Diatonic Melody FragmentsDocument1 pageDiatonic Melody FragmentssimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Late 1960s: You Can Do What You Want ToDocument4 pagesThe Late 1960s: You Can Do What You Want TosimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Intro MidiDocument16 pagesIntro Midiwizard_of_keysNo ratings yet

- A Revolution in Pop Music - 1960sDocument3 pagesA Revolution in Pop Music - 1960ssimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Concert Details For ParentsDocument7 pagesConcert Details For ParentssimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- Distribution FormatsDocument2 pagesDistribution Formatsmws_97No ratings yet

- History of RecordingDocument6 pagesHistory of RecordingMatt Gooch0% (1)

- Rock and RollDocument3 pagesRock and RollsimonballemusicNo ratings yet

- The Development of Technology-Based Music 3 - InstrumentsDocument5 pagesThe Development of Technology-Based Music 3 - Instrumentssimonballemusic100% (1)

- Indercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDocument294 pagesIndercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDr Sneha's Skin and Allergy Clinic IndiaNo ratings yet

- Case Study of A Condemned Boiler & Methods To Re-Establish ItDocument43 pagesCase Study of A Condemned Boiler & Methods To Re-Establish Its sivaNo ratings yet

- Government of Karnataka: Only For Birth Verification PurposeDocument1 pageGovernment of Karnataka: Only For Birth Verification PurposeAmit VantagodiNo ratings yet

- UnpublishedDocument7 pagesUnpublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- ANALE - Stiinte Economice - Vol 2 - 2014 - FinalDocument250 pagesANALE - Stiinte Economice - Vol 2 - 2014 - FinalmhldcnNo ratings yet

- Design and Synthesis of Zinc (Ii) Complexes With Schiff Base Derived From 6-Aminopenicillanic Acid and Heterocyclic AldehydesDocument6 pagesDesign and Synthesis of Zinc (Ii) Complexes With Schiff Base Derived From 6-Aminopenicillanic Acid and Heterocyclic AldehydesIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Answer KeyDocument21 pagesAnswer KeyJunem S. Beli-otNo ratings yet

- Lf-74 Wire Feeder: Operator's ManualDocument50 pagesLf-74 Wire Feeder: Operator's ManualLuis Eduardo Cesena De La VegaNo ratings yet

- Term Paper (Dev - Econ-2)Document14 pagesTerm Paper (Dev - Econ-2)acharya.arpan08No ratings yet

- Metals and Non Metals NotesDocument3 pagesMetals and Non Metals NotesVUDATHU SHASHIK MEHERNo ratings yet

- Performance Evaluation of Selected Ceramic Companies of BangladeshDocument14 pagesPerformance Evaluation of Selected Ceramic Companies of BangladeshmotaazizNo ratings yet

- Deed of DonationDocument2 pagesDeed of DonationMary RockwellNo ratings yet

- AUDCISE Unit 3 Worksheets Agner, Jam Althea ODocument3 pagesAUDCISE Unit 3 Worksheets Agner, Jam Althea OdfsdNo ratings yet

- Question Bank FormatDocument5 pagesQuestion Bank Formatmahidpr18No ratings yet

- The Entrepreneurial and Entrepreneurial Mind: Week #2Document20 pagesThe Entrepreneurial and Entrepreneurial Mind: Week #2Mr.BaiGNo ratings yet

- The Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeDocument6 pagesThe Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeVikram Singh ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Appeals Composition and TranslationDocument54 pagesRhetorical Appeals Composition and Translationteacher briculNo ratings yet

- UNIT 3 Part 1-Propositional LogicDocument11 pagesUNIT 3 Part 1-Propositional LogicVanshika ChauhanNo ratings yet

- If ملخص قواعدDocument2 pagesIf ملخص قواعدAhmed GaninyNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 04 - Lecture Mod PDFDocument72 pagesChapter - 04 - Lecture Mod PDFtahirNo ratings yet

- User Manual of CUBOIDDocument50 pagesUser Manual of CUBOIDshahinur rahmanNo ratings yet

- The Law of ParkinsonDocument5 pagesThe Law of Parkinsonathanassiadis2890No ratings yet

- Ethnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesDocument13 pagesEthnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesJeff Bryan Arellano HimorNo ratings yet

- SB KarbonDocument3 pagesSB KarbonAbdul KarimNo ratings yet

- Study Session8Document1 pageStudy Session8MOSESNo ratings yet

- Project Summary, WOFDocument2 pagesProject Summary, WOFEsha GargNo ratings yet

- Usb MSC Boot 1.0Document19 pagesUsb MSC Boot 1.0T.h. JeongNo ratings yet

- Veterinary MicrobiologyDocument206 pagesVeterinary MicrobiologyHomosapienNo ratings yet