Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Archer13

Archer13

Uploaded by

jiejialing08Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Normas NES M1019Document12 pagesNormas NES M1019Margarita Torres FloresNo ratings yet

- The Objectives of Islamic AccountingDocument3 pagesThe Objectives of Islamic AccountingNur Rasyidah Ab HalimNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Islamic Accounting Theory and Practice PDFDocument256 pagesAn Introduction To Islamic Accounting Theory and Practice PDFArif Witjaksoeno100% (6)

- Islamic Accounting-Article 3Document7 pagesIslamic Accounting-Article 3Mohd Firdaus Abd LatifNo ratings yet

- List of Documents NBA PfilesDocument48 pagesList of Documents NBA PfilesDr. A. Pathanjali Sastri100% (1)

- Napier Haniffa Introduction To Islamic Accounting 2011Document14 pagesNapier Haniffa Introduction To Islamic Accounting 2011OwlNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Islamic AccountingDocument19 pagesMeaning of Islamic Accountingturk66650% (2)

- The Influence of Riba and Zakat OnDocument19 pagesThe Influence of Riba and Zakat Onekaitzbengoetxea857No ratings yet

- Bill MaurerDocument10 pagesBill MaurerZeeshanSameenNo ratings yet

- CHP - 06 Islamic Accounting Literature ReviewDocument66 pagesCHP - 06 Islamic Accounting Literature ReviewDr. Shahul Hameed bin Mohamed Ibrahim100% (4)

- The Two Ws of Islamic Accounting Research: EditorialDocument5 pagesThe Two Ws of Islamic Accounting Research: EditorialFaten FatihahNo ratings yet

- Eltegani - Accounting PostulatesDocument18 pagesEltegani - Accounting PostulatesYazlin YusofNo ratings yet

- Accounting Treatment For Corporate ZakatDocument14 pagesAccounting Treatment For Corporate ZakatCheng CheongNo ratings yet

- Acc ShariahDocument4 pagesAcc Shariahbobby perdanaNo ratings yet

- Baydoun Willett (2000) Islamic Corporate Reports PDFDocument20 pagesBaydoun Willett (2000) Islamic Corporate Reports PDFAqilahAzmiNo ratings yet

- Dwiki Cahyo y 7211417163Document8 pagesDwiki Cahyo y 7211417163Dwiki ChyoNo ratings yet

- Product DescriptionDocument9 pagesProduct DescriptionNOREDINE KINANNo ratings yet

- Islamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al ShariahDocument54 pagesIslamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al ShariahNader MehdawiNo ratings yet

- Islamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al-ShariahDocument54 pagesIslamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al-Shariahmughees100% (1)

- Haniffa, R. & Hudaib, M. (2011) A Conceptual Framework For Islamic Accounting, in Napier, C. & Haniffa, R. (Eds.), Islamic Accounting, Edward ElgarDocument44 pagesHaniffa, R. & Hudaib, M. (2011) A Conceptual Framework For Islamic Accounting, in Napier, C. & Haniffa, R. (Eds.), Islamic Accounting, Edward ElgarPT DNo ratings yet

- Baydoun Willett 2000 Islamic Corporate ReportsDocument20 pagesBaydoun Willett 2000 Islamic Corporate ReportsBen James100% (2)

- Accounting Treatment For Corporate Zakat: A Critical Review: Imefm 2,1Document15 pagesAccounting Treatment For Corporate Zakat: A Critical Review: Imefm 2,1delimasalbutNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7Document44 pagesLecture 7Amran Bin Ismail RunsNo ratings yet

- Overview of Islamic AccountingDocument25 pagesOverview of Islamic AccountingNovi WulandariNo ratings yet

- Sharia AccountingDocument9 pagesSharia AccountingIvana YustitiaNo ratings yet

- Accounting SystemsDocument1 pageAccounting SystemsHafij UllahNo ratings yet

- CH11 - Summary, Conclusions, and SuggestDocument10 pagesCH11 - Summary, Conclusions, and SuggestJANUAR CHRISTIANTONo ratings yet

- Islamic Accounting Case StudyDocument9 pagesIslamic Accounting Case StudyRabeeka SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Acctg in Islamic BanksDocument43 pagesAcctg in Islamic BanksJanggo KuatNo ratings yet

- 10 1108 - PRR 05 2021 0024Document16 pages10 1108 - PRR 05 2021 0024Abu BakarNo ratings yet

- Islamic Accounting: Introduction To IA: Foundation & DevelopmentDocument52 pagesIslamic Accounting: Introduction To IA: Foundation & DevelopmentNuranis QhaleedaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 - Part 1Document10 pagesCHAPTER 2 - Part 1hassah fahadNo ratings yet

- Conventional Accounting Versus Sharia Accounting: Reconciliation of Perception To Achieve Spiritual MeaningDocument6 pagesConventional Accounting Versus Sharia Accounting: Reconciliation of Perception To Achieve Spiritual Meaninggrizzly hereNo ratings yet

- Project BANK330201610308Document29 pagesProject BANK330201610308Mohamed Aziz BltaifNo ratings yet

- An Overview On The Basics of Islamic AuditDocument10 pagesAn Overview On The Basics of Islamic AuditAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document22 pagesChapter 1Abdiwahab AbdikadirNo ratings yet

- Development in Legal Issues of Corporate Governance in Islamic Finance PDFDocument25 pagesDevelopment in Legal Issues of Corporate Governance in Islamic Finance PDFDwiki ChyoNo ratings yet

- Risk Analysis For Islamic Banks: Hennie Van Greuning and Zamir IqbalDocument8 pagesRisk Analysis For Islamic Banks: Hennie Van Greuning and Zamir IqbalsmilbuyNo ratings yet

- CHP 1 Abdur Rahman Abdur Raheem Introduction To Islamic Accounting Practice and Theory 9 32Document24 pagesCHP 1 Abdur Rahman Abdur Raheem Introduction To Islamic Accounting Practice and Theory 9 32Asfa AsfiaNo ratings yet

- Islamic Accounting StandardsDocument64 pagesIslamic Accounting StandardsDawood Mohmand50% (2)

- Islamic Banking and Shariah Compliance-Habib Ahmed-Drham University-UK-for ULDocument9 pagesIslamic Banking and Shariah Compliance-Habib Ahmed-Drham University-UK-for ULMaha AtifNo ratings yet

- Product Development in Islamic Banks PDFDocument5 pagesProduct Development in Islamic Banks PDFNatarajan JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Product Development in Islamic BanksDocument5 pagesProduct Development in Islamic BanksNatarajan JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Ravi ReportDocument9 pagesRavi ReportAli RawaniNo ratings yet

- Kel 3 - Shariah Compliance Parameter - Saiful AzharDocument15 pagesKel 3 - Shariah Compliance Parameter - Saiful Azharayu nailil kiromahNo ratings yet

- A Critique On Accounting For Murabaha Contract A Comparative Analysis of IFRS and AAOIFI Accounting Standards PDFDocument13 pagesA Critique On Accounting For Murabaha Contract A Comparative Analysis of IFRS and AAOIFI Accounting Standards PDFAhmad BaehaqiNo ratings yet

- Admin,+13 CIMAE Rifqi EndDocument13 pagesAdmin,+13 CIMAE Rifqi EndHafiz RezaNo ratings yet

- The Implementation of Sukuk Ijarah in MalaysiaDocument67 pagesThe Implementation of Sukuk Ijarah in Malaysiaetty100% (6)

- A Guide To Accounting ZAKAHDocument97 pagesA Guide To Accounting ZAKAHZahid RehmanNo ratings yet

- Creative Accounting Ethical Issues of Micro and Macro Manipulation PDFDocument11 pagesCreative Accounting Ethical Issues of Micro and Macro Manipulation PDFAđńaŋ NèeþuNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting and Analysis MaterialDocument132 pagesFinancial Accounting and Analysis MaterialkarthikreddyNo ratings yet

- Islamic Banking Ideal N RealityDocument19 pagesIslamic Banking Ideal N RealityIbnu TaimiyyahNo ratings yet

- Concept of Revenue, Expenses and Liabilities in Accounting For Zakat, Waqf and Baitulmal in Malaysia: An Analysis From Shariah PerspectiveDocument16 pagesConcept of Revenue, Expenses and Liabilities in Accounting For Zakat, Waqf and Baitulmal in Malaysia: An Analysis From Shariah PerspectivesuhaileresmairNo ratings yet

- Social Reporting by Islamic BanksDocument24 pagesSocial Reporting by Islamic BanksAyman Ahmed CheemaNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting For Islamic Banking Products: Learning ObjectivesDocument21 pagesFinancial Accounting For Islamic Banking Products: Learning ObjectivesAbdelnasir HaiderNo ratings yet

- Islamic Banking and Shari'Ah ComplianceDocument15 pagesIslamic Banking and Shari'Ah Compliancesiddiq elzar100% (1)

- Demand For and Supply of Mark-Up and Pls Funds in Islamic Banking: Some Alternative ExplanationsDocument46 pagesDemand For and Supply of Mark-Up and Pls Funds in Islamic Banking: Some Alternative ExplanationsfarahNo ratings yet

- Islamic Finance in a Nutshell: A Guide for Non-SpecialistsFrom EverandIslamic Finance in a Nutshell: A Guide for Non-SpecialistsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Capital Structure and Corporate Financing Decisions: Theory, Evidence, and PracticeFrom EverandCapital Structure and Corporate Financing Decisions: Theory, Evidence, and PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Syllabus for ENG-1B-45999 OL (06_17-07_25) Critical Thinking_WritingDocument5 pagesSyllabus for ENG-1B-45999 OL (06_17-07_25) Critical Thinking_Writingjiejialing08No ratings yet

- MARK3088 - Lecture Wk 5 - New Product Idea GenerationDocument46 pagesMARK3088 - Lecture Wk 5 - New Product Idea Generationjiejialing08No ratings yet

- e56c58ed40004cbce696d41ee0347a78apm_coursework(2)Document4 pagese56c58ed40004cbce696d41ee0347a78apm_coursework(2)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- SM ASSIGNMENT 1Document2 pagesSM ASSIGNMENT 1jiejialing08No ratings yet

- SM MIDTERM EXAMDocument2 pagesSM MIDTERM EXAMjiejialing08No ratings yet

- HIST 11 NotesDocument52 pagesHIST 11 Notesjiejialing08No ratings yet

- ACCT5919 Individual Assignment and Reflection Term 2 2024(5)Document3 pagesACCT5919 Individual Assignment and Reflection Term 2 2024(5)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- [9789004233041 - Crossing Boundaries] Crossing BoundariesDocument273 pages[9789004233041 - Crossing Boundaries] Crossing Boundariesjiejialing08No ratings yet

- MCD2080 Business Statistics Group Assignment-FinalDocument5 pagesMCD2080 Business Statistics Group Assignment-Finaljiejialing08No ratings yet

- 4a_Convolutional_Neural_NetworksDocument56 pages4a_Convolutional_Neural_Networksjiejialing08No ratings yet

- _I Need U_Document21 pages_I Need U_jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240415 125.364 Week 06 Interest rate swapDocument21 pages20240415 125.364 Week 06 Interest rate swapjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Option 1_Advertisment Design CanvasDocument2 pagesAssignment 2 Option 1_Advertisment Design Canvasjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Option 3_Store Design CanvasDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 Option 3_Store Design Canvasjiejialing08No ratings yet

- 大纲 MARK3088 Assessment Guide 2024 T2Document14 pages大纲 MARK3088 Assessment Guide 2024 T2jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240319 125.364 Week 04-05 Part 01Document25 pages20240319 125.364 Week 04-05 Part 01jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240325 125.364 Week 05Document41 pages20240325 125.364 Week 05jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240226_125.364 Week 01Document61 pages20240226_125.364 Week 01jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240312_125.364 Topic03Document45 pages20240312_125.364 Topic03jiejialing08No ratings yet

- Segment reporting exam question 2015 (1)Document2 pagesSegment reporting exam question 2015 (1)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- Week 8 Lecture - Sustainability and climate change reporting (2)Document32 pagesWeek 8 Lecture - Sustainability and climate change reporting (2)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- Massey Uni Sustainability reporting-Final2Document23 pagesMassey Uni Sustainability reporting-Final2jiejialing08No ratings yet

- WEEK 2 LECTURE SLIDESDocument29 pagesWEEK 2 LECTURE SLIDESjiejialing08No ratings yet

- General Concepts of IncomeDocument16 pagesGeneral Concepts of Incomejiejialing08No ratings yet

- Week 3 LECTURE SLIDESDocument53 pagesWeek 3 LECTURE SLIDESjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Income from PropertyDocument12 pagesIncome from Propertyjiejialing08No ratings yet

- WEEK 6 LECTURE SLIDESDocument46 pagesWEEK 6 LECTURE SLIDESjiejialing08No ratings yet

- IRAC MethodDocument13 pagesIRAC Methodjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Week (1) lectureDocument25 pagesWeek (1) lecturejiejialing08No ratings yet

- Babst Vs CA PDFDocument17 pagesBabst Vs CA PDFJustin YañezNo ratings yet

- SB KarbonDocument3 pagesSB KarbonAbdul KarimNo ratings yet

- Task Force On Sexual Assault and Interpersonal Violence Final Report 2014-15Document16 pagesTask Force On Sexual Assault and Interpersonal Violence Final Report 2014-15Fourth EstateNo ratings yet

- Ethnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesDocument13 pagesEthnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesJeff Bryan Arellano HimorNo ratings yet

- Major Landforms of The Earth NotesDocument3 pagesMajor Landforms of The Earth NotesSIMMA SAI PRASANNANo ratings yet

- Palaycheck System Based Rice Cultivation in The PhilippinesDocument125 pagesPalaycheck System Based Rice Cultivation in The PhilippinesRizalito BenitoNo ratings yet

- Greece Education Foundation Courses and Gces 10 2010Document6 pagesGreece Education Foundation Courses and Gces 10 2010Stamatios KarapournosNo ratings yet

- Report On Tapal by AliDocument72 pagesReport On Tapal by AliAli Xydi87% (15)

- GIDC Rajju Shroff ROFEL Institute of Management Studies: Subject:-CRVDocument7 pagesGIDC Rajju Shroff ROFEL Institute of Management Studies: Subject:-CRVIranshah MakerNo ratings yet

- Phd:304 Lab Report Advanced Mathematical Physics: Sachin Singh Rawat 16PH-06 (Department of Physics)Document12 pagesPhd:304 Lab Report Advanced Mathematical Physics: Sachin Singh Rawat 16PH-06 (Department of Physics)sachin rawatNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Research 1Document7 pagesAssignment in Research 1cpmac123No ratings yet

- Grade 2 - 1ST Periodical TestDocument5 pagesGrade 2 - 1ST Periodical TestGAY IBANEZ100% (1)

- Free Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGADocument31 pagesFree Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGAAmit AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Referee Report TemplateDocument2 pagesReferee Report TemplateAna Jufriani100% (1)

- Sports Competence ResearchDocument11 pagesSports Competence ResearchHanna Relator DolorNo ratings yet

- The Role of Green InfrastractureDocument18 pagesThe Role of Green InfrastractureYonaminos Taye WassieNo ratings yet

- Logging Best Practices Guide PDFDocument12 pagesLogging Best Practices Guide PDFbnanduriNo ratings yet

- Test Method For DDF ProjectDocument13 pagesTest Method For DDF ProjectrantosbNo ratings yet

- Whyte Human Rights and The Collateral Damage oDocument16 pagesWhyte Human Rights and The Collateral Damage ojswhy1No ratings yet

- Linkages and NetworkDocument28 pagesLinkages and NetworkJoltzen GuarticoNo ratings yet

- List Peserta Swab Antigen - 5 Juni 2021Document11 pagesList Peserta Swab Antigen - 5 Juni 2021minhyun hwangNo ratings yet

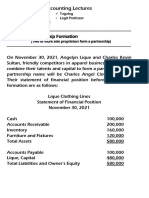

- 8 Lec 03 - Partnership Formation With BusinessDocument2 pages8 Lec 03 - Partnership Formation With BusinessNathalie GetinoNo ratings yet

- English Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesDocument18 pagesEnglish Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesLanping FuNo ratings yet

- Consultancy - Software DeveloperDocument2 pagesConsultancy - Software DeveloperImadeddinNo ratings yet

- Indercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDocument294 pagesIndercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDr Sneha's Skin and Allergy Clinic IndiaNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument9 pagesReportshobhaNo ratings yet

- PYF Biennial Conference Vawi 19-NaDocument1 pagePYF Biennial Conference Vawi 19-NaMizoram Presbyterian Church SynodNo ratings yet

- Gentrification in Color and TimeDocument38 pagesGentrification in Color and TimeBNo ratings yet

Archer13

Archer13

Uploaded by

jiejialing08Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Archer13

Archer13

Uploaded by

jiejialing08Copyright:

Available Formats

744 Book Reviews

KPMG LLP, S. M. Glover, and D. F. Prawitt. 2012. Enhancing board oversight: Avoiding judgment

traps and biases. Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission. Available

at: http://www.kpmg.com/cn/en/issuesandinsights/articlespublications/pages/enhancing-board-

oversight-201209.aspx

Kravitz, D. A., and B. Martin. 1986. Ringelmann rediscovered: The original article. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology 50 (5): 936–941.

Schrand, C. M., and S. Zechman. 2012. Executive overconfidence and the slippery slope to financial

misreporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53: 311–329.

Swieringa, R., and K. Weick. 1982. An assessment of laboratory experiments in accounting. Journal of

Accounting Research 20 (Supplement): 56–101.

ROBERT J. SWIERINGA3

Professor of Accounting

Cornell University

CHRISTOPHER NAPIER and ROSZAINI HANIFFA (editors), Islamic Accounting

(Cheltenham, Glos, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2011, ISBN 978-1-

84844-220-7, pp. xx, 740).

What is to be understood by the term ‘‘Islamic accounting’’? The question has arisen in the context of the

development of the Islamic financial services industry (IFSI) in recent decades. The raison d’être of IFSI is

Islamic religious law, the Shari’a, and its interpretations in Islamic commercial jurisprudence, the Fiqh al

Muamalat, according to which certain forms of transactions and financial instruments that are widely employed

in conventional finance, as well as the conducting or financing of activities connected with alcohol, pork,

gambling, and armaments, are prohibited. These include (the Arabic terms are in brackets): any form of interest

receipts or payments [riba], short selling and speculation in general [maysir], and vagueness or ambiguity of

contractual outcomes [gharrar]. Islamic finance, therefore, uses forms of contract based on Fiqh al Muamalat

(known as the ‘‘nominate contracts’’) and financial instruments which avoid these prohibited elements. The

resulting transactions call for specific accounting treatments that may not be indicated within ‘‘generally

accepted accounting principles’’ such as U.S. GAAP or the International Accounting Standards Board’s

(IASB) IASs and IFRSs. For this reason, a specialized accounting standards body, the Accounting and

Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI), was set up in 1991, and has since issued

around 25 financial accounting standards.

In a narrow sense, ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ might, therefore, be understood as accounting as required by

AAOIFI’s standards, although such a usage is debatable for reasons I will give below. However, for the editors

of this weighty collection of 33 papers (most of which have been previously published in journals, and are

reproduced from the originals) plus an introductory chapter, the term has a much wider sense or set of senses.

In the introductory chapter, written by the editors and entitled ‘‘An Islamic Perspective of Accounting,’’ the

narrow sense is presented first. The second sense that they mention is associated with notions of social

responsibility within a framework of religious ethics: accounting is seen through the lens of a corporate

governance (CG) framework that, in contrast to the neo-liberal and secular perspective that characterizes the

U.S. and U.K. approach to CG, with its emphasis on the rights of investors and creditors, stresses

accountability to God for socially responsible behavior (including transparency and fair dealing, as well as

environmental sustainability). While the first, narrow sense of ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ is concerned with

technical issues such as recognition, classification, and measurement, as well as disclosure, this second sense is

particularly concerned with the latter, as well as with corporate governance more generally. A third sense of the

term is suggested by the need for accounting treatments to provide an appropriate basis for determining liability

to zakat, a type of wealth tax or obligatory (for Muslims) religious levy intended to finance social causes such

as the alleviation of poverty. The book also contains papers concerned with the auditing of Islamic financial

3

Robert Swieringa has been serving on the board of directors of General Electric Company since 2002.

The Accounting Review

March 2013

Book Reviews 745

institutions and with the history of accounting in the Islamic world, as well as a paper on management

accounting systems in Islamic and conventional banks.

As its title suggests, the general thrust of the book’s contents is Islamic particularism in accounting;

namely, the thesis that accounting (in the broad sense together with corporate governance), as envisioned and

practiced from an Islamic perspective, is qualitatively and not just technically different from conventional

accounting. The second sense of the term ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ is, thus, clearly central to this thesis. However,

the book contains only a minority (less than 25 percent) of empirical papers, and it is to these that reference

must primarily be made in assessing to what extent the thesis is effectively supported.

After the introductory chapter by the editors, the book is divided into six parts: Conceptual Framework for

Islamic Accounting (three papers); Accounting Ethics and Social Responsibility (seven papers); Corporate

Reporting (nine papers); Accounting Practice and Zakat (seven papers); Auditing (three papers); and Islamic

History of Accounting (four papers).

In Part I, a particularly significant paper (Chapter 2) is that by Rifaat Ahmed Abdel Karim, who was at the

time secretary-general of AAOIFI. The author explains the rationale for the setting up of AAOIFI (under its

initial name, the Financial and Accounting Organization for Islamic Banks and Financial Institutions

[FAOIBFI]). The context of the financial reporting issues and problems faced by Islamic banks are also well

explained in the previous paper (Chapter 1), by Moustafa F. Adbel-Magid.

Dr. Karim states that two options were considered by FAOIBFI in developing objectives of financial

accounting (for Islamic financial institutions):

1. Establish objectives based on the principles of Islam and its teachings and then consider these

established objectives in relation to contemporary accounting thought; or

2. Start with objectives established in contemporary accounting thought, test them against Islamic

Shari’a, accept those that are consistent with Shari’a, and reject those that are not. (p. 31)

The author tells us that after a lengthy process of discussions involving accounting academics and

practitioners, Shari’a scholars, Islamic bankers, and officials in central banks, it was agreed that the second

approach should be adopted. Both approaches were considered to be in compliance with Shari’a precepts, so

that there was no reason to reject the second approach. Moreover, a similar approach was adopted in

developing the concepts of financial accounting, which comprised the following:

(a) The identification of accounting concepts which have been previously developed by other institutions,

which are consistent with the Islamic ideals of accuracy and fairness.

(b) The identification of concepts which are used in traditional financial accounting but which are

inconsistent with Islamic Shari’a, which were either rejected or sufficiently modified to comply with

the Shari’a.

(c) The development of those concepts defining certain aspects of financial accounting for Islamic banks

that are unique to the Islamic way of transacting business. (p. 32)

An example of the issue mentioned under (c), above, is the recognition of profit under a type of Islamic

credit sale transaction known by the name of the ‘‘nominate contract’’ employed as Murabaha, which is a sale

at cost (which must be disclosed) plus a mark-up or gross profit margin. Payment of the Murabaha price is

typically made by installments, which raises the question of how the profit element should be recognized.

According to IAS 18, the financial element of the profit (or interest) should be recognized pro rata temporis,

using the ‘‘effective interest rate’’ method, while the nonfinancial element should be recognized when the sale

takes place. However, the Murabaha mark-up is not interest, and Islamic banks could interpret IAS 18 in

various ways, either to recognize all of the mark-up as profit at the time of the sale, or to recognize it as profit at

the conclusion of the contract (when the final payment is made), or, indeed, by various methods of recognition

pro rata temporis. One might suggest that the mark-up could be decomposed into the ‘‘pure interest’’ element

and the ‘‘pure gross profit’’ element by reference to prevailing market interest rates, but that would in fact be an

example (to quote from (b), above) of a concept ‘‘used in traditional financial accounting but . . . inconsistent

with Islamic Shari’a.’’ AAOIFI, in its financial accounting standard on Murabaha, settled on a method of

recognition of the entire mark-up as profit pro rata temporis.

The author’s explanations of the raison d’être of AAOIFI and its standards are amplified in another paper

by him, which appears as Chapter 12 in Part III of the collection. A paper in Part IV of the collection, which

appears as Chapter 24, by Ros Aniza Mohd. Shariff and Abdul Rahim Abdul Rahman, provides further support

The Accounting Review

March 2013

746 Book Reviews

to the proposition that accounting practices for Islamic transactions (in this case, Islamic leases) are divergent

in the absence of generally accepted and applicable financial reporting standards.

The papers by Dr. Karim present a particularly well-informed view of what may be meant by ‘‘Islamic

accounting’’ in the first, narrow sense mentioned above in a financial accounting standard-setting context,

namely, accounting based on the second of the two options considered by FAOIBFI/AAOIFI. In contrast, most

other papers in the collection seem to favor the first of the two options. For example, in the following paper

(Chapter 3), Roszaini Haniffa (one of the editors) and Mohammad Abdullah Hudaib take the view that

‘‘[b]ased on the limitations of conventional Western accounting, the Shari’a Islami’iah is proposed as the

foundation in building a theoretical framework for IPA [the Islamic perspective of accounting]’’ (p. 43). Other

papers in the collection also seek to link the notion of ‘‘the Islamic perspective of accounting’’ with a more

general critical perspective on accounting; for example, in Chapter 17 by Rania Kamla, Sonja Gallhofer and

Jim Haslam, which links Islamic principles and accounting for the environment within a critical perspective.

We have, therefore, in this collection a contrast between:

(a) a minimalist version of the first sense of ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ mentioned above; namely, a practical

view of the need to improve the quality of financial accounting and reporting of Islamic financial

institutions; i.e., not ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ as such, but rather accounting that fairly presents the results

of certain transactions that comply with the Islamic Shari’a when the application of conventional U.S.

or IASB GAAP would not do so (see the Murabaha example above); and

(b) the second, broader, and more radical sense of ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ mentioned above; namely, a

view of Islamic accounting (or financial accounting, reporting, and corporate governance) as

reflecting Islamic religious ethics in such a way as to make these different in principle from

conventional financial accounting, reporting, and corporate governance, which are seen as reflecting a

secular, materialist, and arguably amoral world view.

Whether this more radical sense of ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ is significantly reflected in practice is an issue on

which the empirically based papers in this collection should be able to shed light. It is, therefore, to these that I

will now turn. While none of the papers in Part II, Accounting Ethics and Social Responsibility, are empirically

based, three of the papers in Part III, Corporate Reporting, are. The same is true of one paper in Part IV,

Accounting Practice and Zakat. These papers cast light on the extent to which the more radical sense of

‘‘Islamic accounting’’ is significantly reflected in practice. Three other empirically based papers are included in

the collection, Chapters 25 and 26 in Part VI and Chapter 29 in Part V, but as they do not bear on the issue

identified above, they will not be examined here.

Chapter 16, a paper by Maliah Sulaiman, reports the results of a ‘‘laboratory experiment’’ using students

as surrogates for investors in testing whether certain financial reporting methods developed by Baydoun and

Willett (1994, 2000), namely, a current value balance sheet (CVBS) and a value added statement (VAS), which

the authors argue are more consistent with Islamic principles than a historical cost balance sheet (HCBS) and a

statement of profit and loss (PL), would in practice be found to be preferable to, or more important than, the

latter. The results indicated that Muslim subjects did not accord significantly greater importance to the CVBS

and VAS compared to the HCBS and PL. Nor were the Muslim subjects’ responses significantly different from

those of non-Muslims. The author concluded that ‘‘the suggestion that Muslims ought to be provided with

financial information of a different character from what is normally disclosed in Western-based accounting

systems, seems to have little support’’ (p. 380; emphasis in the original).

Chapter 18, a paper by Bassam Maali, Peter Casson, and Christopher Napier (the latter being one of the

editors), examines the extent to which social reporting by Islamic banks conforms to a ‘‘benchmark set of social

disclosures . . . derived by applying Islamic principles in an a priori manner’’ (p. 417). The authors conclude:

‘‘Contrary to our expectations, the empirical findings suggest that social issues are not of major concern for

most Islamic banks’’ (p. 425).

In Chapter 19, a paper by Roszaini Haniffa and Mohammad Hudaib, the authors ‘‘attempt to assess the

degree of variation of communicated ethical identity . . . against a benchmark of ideal ethical identity’’ for

Islamic banks (p. 431). This variation is measured by what the authors call the Ethical Identity Index (EII). The

EII is composed of 78 constructs grouped under eight dimensions. The dimensions are: vision and mission

statement; board of directors and top management; products; Zakah, charity, and benevolent loans; employees;

debtors; community; and Shari’a supervisory board (internal supervision of Shari’a compliance). Using

content analysis, the corporate annual reports of seven Islamic banks for the period 2002–2004 were scored on

The Accounting Review

March 2013

Book Reviews 747

the basis of the EII. The highest score was 65 percent, while the lowest was only 16 percent, and the three-year

means for the other five banks ranged from 28 percent to 48 percent, which, as the authors note (with surprise),

‘‘suggest[ed] a large disparity between the communicated and the ideal ethical identities’’ (p. 444, italics in the

original).

The findings of these empirically based papers strongly suggest that the more radical sense of ‘‘Islamic

accounting’’ is an ideal that is present in the minds of a number of academicians (and maybe others), but is not

reflected in practice. In other words, the notion of ‘‘compliance with the Shari’a,’’ which is reflected in the

practice of Islamic banks, does not encompass, to any significant degree, ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ in this sense

(including financial reporting and corporate governance). Nevertheless, compliance with the Shari’a is the

raison d’être of Islamic banks. Hence, such compliance must apparently be understood as not implying the

need to practice ‘‘Islamic accounting’’ in the more radical sense.

How, then, is such compliance to be understood? What seems to be important is the avoidance of

prohibited types of transactions such as charging or paying interest or speculation by short selling, and of

strictly prohibited business activities, such as those associated with arms manufacture, alcohol, pork, and

gambling, and, in particular, the use of the Shari’a-compliant nominate contracts provided by the Fiqh al

Muamalat (Islamic commercial jurisprudence) as a basis for financial transactions and instruments. Apart from

avoidance of the prohibited business activities, the use of such contracts as a basis for an Islamic bank’s

operations constitutes compliance in a narrow, formal ( juristic or legalistic) sense, rather than in the broader

and more substantive sense of compliance in practice with Islamic ethical precepts, such as those of socially

and environmentally responsible business conduct.

Thus, what appears to be the thesis of the editors of this collection of papers, namely, that accounting, in a

broad sense encompassing financial reporting and corporate governance, as envisioned and practiced from an

Islamic perspective is qualitatively (and not just technically) different from conventional accounting, is not, in

fact, borne out when the empirically based papers in the collection are considered. Even the technical

differences, due to the need for specific rules for the financial reporting of the results of certain

Shari’a-compliant transactions, barely constitute ‘‘Islamic accounting.’’

Notwithstanding this lack of coherence, the papers in the collection are well written and well presented

(although some are quite old), and a number of them are very informative for readers such as academicians and

graduate students interested in Islamic finance. These papers include the editors’ introduction, the two papers

by Rifaat Ahmed Abdel Karim, and the various empirically based papers cited above. I would not recommend

the book to practitioners or to undergraduate students.

REFERENCES

Baydoun, N., and R. Willett. 1994. Islamic accounting theory. Paper presented at the AAANZ Annual

Conference, Sydney, Australia.

Baydoun, N., and R. Willett. 2000. Islamic corporate reports. Abacus 36 (1): 71–90.

SIMON ARCHER

Visiting Professor in Islamic Finance

University of Reading

The Accounting Review

March 2013

You might also like

- Normas NES M1019Document12 pagesNormas NES M1019Margarita Torres FloresNo ratings yet

- The Objectives of Islamic AccountingDocument3 pagesThe Objectives of Islamic AccountingNur Rasyidah Ab HalimNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Islamic Accounting Theory and Practice PDFDocument256 pagesAn Introduction To Islamic Accounting Theory and Practice PDFArif Witjaksoeno100% (6)

- Islamic Accounting-Article 3Document7 pagesIslamic Accounting-Article 3Mohd Firdaus Abd LatifNo ratings yet

- List of Documents NBA PfilesDocument48 pagesList of Documents NBA PfilesDr. A. Pathanjali Sastri100% (1)

- Napier Haniffa Introduction To Islamic Accounting 2011Document14 pagesNapier Haniffa Introduction To Islamic Accounting 2011OwlNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Islamic AccountingDocument19 pagesMeaning of Islamic Accountingturk66650% (2)

- The Influence of Riba and Zakat OnDocument19 pagesThe Influence of Riba and Zakat Onekaitzbengoetxea857No ratings yet

- Bill MaurerDocument10 pagesBill MaurerZeeshanSameenNo ratings yet

- CHP - 06 Islamic Accounting Literature ReviewDocument66 pagesCHP - 06 Islamic Accounting Literature ReviewDr. Shahul Hameed bin Mohamed Ibrahim100% (4)

- The Two Ws of Islamic Accounting Research: EditorialDocument5 pagesThe Two Ws of Islamic Accounting Research: EditorialFaten FatihahNo ratings yet

- Eltegani - Accounting PostulatesDocument18 pagesEltegani - Accounting PostulatesYazlin YusofNo ratings yet

- Accounting Treatment For Corporate ZakatDocument14 pagesAccounting Treatment For Corporate ZakatCheng CheongNo ratings yet

- Acc ShariahDocument4 pagesAcc Shariahbobby perdanaNo ratings yet

- Baydoun Willett (2000) Islamic Corporate Reports PDFDocument20 pagesBaydoun Willett (2000) Islamic Corporate Reports PDFAqilahAzmiNo ratings yet

- Dwiki Cahyo y 7211417163Document8 pagesDwiki Cahyo y 7211417163Dwiki ChyoNo ratings yet

- Product DescriptionDocument9 pagesProduct DescriptionNOREDINE KINANNo ratings yet

- Islamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al ShariahDocument54 pagesIslamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al ShariahNader MehdawiNo ratings yet

- Islamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al-ShariahDocument54 pagesIslamic Finance and Their Financial Growth Verses Their Maqasid Al-Shariahmughees100% (1)

- Haniffa, R. & Hudaib, M. (2011) A Conceptual Framework For Islamic Accounting, in Napier, C. & Haniffa, R. (Eds.), Islamic Accounting, Edward ElgarDocument44 pagesHaniffa, R. & Hudaib, M. (2011) A Conceptual Framework For Islamic Accounting, in Napier, C. & Haniffa, R. (Eds.), Islamic Accounting, Edward ElgarPT DNo ratings yet

- Baydoun Willett 2000 Islamic Corporate ReportsDocument20 pagesBaydoun Willett 2000 Islamic Corporate ReportsBen James100% (2)

- Accounting Treatment For Corporate Zakat: A Critical Review: Imefm 2,1Document15 pagesAccounting Treatment For Corporate Zakat: A Critical Review: Imefm 2,1delimasalbutNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7Document44 pagesLecture 7Amran Bin Ismail RunsNo ratings yet

- Overview of Islamic AccountingDocument25 pagesOverview of Islamic AccountingNovi WulandariNo ratings yet

- Sharia AccountingDocument9 pagesSharia AccountingIvana YustitiaNo ratings yet

- Accounting SystemsDocument1 pageAccounting SystemsHafij UllahNo ratings yet

- CH11 - Summary, Conclusions, and SuggestDocument10 pagesCH11 - Summary, Conclusions, and SuggestJANUAR CHRISTIANTONo ratings yet

- Islamic Accounting Case StudyDocument9 pagesIslamic Accounting Case StudyRabeeka SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Acctg in Islamic BanksDocument43 pagesAcctg in Islamic BanksJanggo KuatNo ratings yet

- 10 1108 - PRR 05 2021 0024Document16 pages10 1108 - PRR 05 2021 0024Abu BakarNo ratings yet

- Islamic Accounting: Introduction To IA: Foundation & DevelopmentDocument52 pagesIslamic Accounting: Introduction To IA: Foundation & DevelopmentNuranis QhaleedaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 - Part 1Document10 pagesCHAPTER 2 - Part 1hassah fahadNo ratings yet

- Conventional Accounting Versus Sharia Accounting: Reconciliation of Perception To Achieve Spiritual MeaningDocument6 pagesConventional Accounting Versus Sharia Accounting: Reconciliation of Perception To Achieve Spiritual Meaninggrizzly hereNo ratings yet

- Project BANK330201610308Document29 pagesProject BANK330201610308Mohamed Aziz BltaifNo ratings yet

- An Overview On The Basics of Islamic AuditDocument10 pagesAn Overview On The Basics of Islamic AuditAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document22 pagesChapter 1Abdiwahab AbdikadirNo ratings yet

- Development in Legal Issues of Corporate Governance in Islamic Finance PDFDocument25 pagesDevelopment in Legal Issues of Corporate Governance in Islamic Finance PDFDwiki ChyoNo ratings yet

- Risk Analysis For Islamic Banks: Hennie Van Greuning and Zamir IqbalDocument8 pagesRisk Analysis For Islamic Banks: Hennie Van Greuning and Zamir IqbalsmilbuyNo ratings yet

- CHP 1 Abdur Rahman Abdur Raheem Introduction To Islamic Accounting Practice and Theory 9 32Document24 pagesCHP 1 Abdur Rahman Abdur Raheem Introduction To Islamic Accounting Practice and Theory 9 32Asfa AsfiaNo ratings yet

- Islamic Accounting StandardsDocument64 pagesIslamic Accounting StandardsDawood Mohmand50% (2)

- Islamic Banking and Shariah Compliance-Habib Ahmed-Drham University-UK-for ULDocument9 pagesIslamic Banking and Shariah Compliance-Habib Ahmed-Drham University-UK-for ULMaha AtifNo ratings yet

- Product Development in Islamic Banks PDFDocument5 pagesProduct Development in Islamic Banks PDFNatarajan JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Product Development in Islamic BanksDocument5 pagesProduct Development in Islamic BanksNatarajan JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Ravi ReportDocument9 pagesRavi ReportAli RawaniNo ratings yet

- Kel 3 - Shariah Compliance Parameter - Saiful AzharDocument15 pagesKel 3 - Shariah Compliance Parameter - Saiful Azharayu nailil kiromahNo ratings yet

- A Critique On Accounting For Murabaha Contract A Comparative Analysis of IFRS and AAOIFI Accounting Standards PDFDocument13 pagesA Critique On Accounting For Murabaha Contract A Comparative Analysis of IFRS and AAOIFI Accounting Standards PDFAhmad BaehaqiNo ratings yet

- Admin,+13 CIMAE Rifqi EndDocument13 pagesAdmin,+13 CIMAE Rifqi EndHafiz RezaNo ratings yet

- The Implementation of Sukuk Ijarah in MalaysiaDocument67 pagesThe Implementation of Sukuk Ijarah in Malaysiaetty100% (6)

- A Guide To Accounting ZAKAHDocument97 pagesA Guide To Accounting ZAKAHZahid RehmanNo ratings yet

- Creative Accounting Ethical Issues of Micro and Macro Manipulation PDFDocument11 pagesCreative Accounting Ethical Issues of Micro and Macro Manipulation PDFAđńaŋ NèeþuNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting and Analysis MaterialDocument132 pagesFinancial Accounting and Analysis MaterialkarthikreddyNo ratings yet

- Islamic Banking Ideal N RealityDocument19 pagesIslamic Banking Ideal N RealityIbnu TaimiyyahNo ratings yet

- Concept of Revenue, Expenses and Liabilities in Accounting For Zakat, Waqf and Baitulmal in Malaysia: An Analysis From Shariah PerspectiveDocument16 pagesConcept of Revenue, Expenses and Liabilities in Accounting For Zakat, Waqf and Baitulmal in Malaysia: An Analysis From Shariah PerspectivesuhaileresmairNo ratings yet

- Social Reporting by Islamic BanksDocument24 pagesSocial Reporting by Islamic BanksAyman Ahmed CheemaNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting For Islamic Banking Products: Learning ObjectivesDocument21 pagesFinancial Accounting For Islamic Banking Products: Learning ObjectivesAbdelnasir HaiderNo ratings yet

- Islamic Banking and Shari'Ah ComplianceDocument15 pagesIslamic Banking and Shari'Ah Compliancesiddiq elzar100% (1)

- Demand For and Supply of Mark-Up and Pls Funds in Islamic Banking: Some Alternative ExplanationsDocument46 pagesDemand For and Supply of Mark-Up and Pls Funds in Islamic Banking: Some Alternative ExplanationsfarahNo ratings yet

- Islamic Finance in a Nutshell: A Guide for Non-SpecialistsFrom EverandIslamic Finance in a Nutshell: A Guide for Non-SpecialistsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Capital Structure and Corporate Financing Decisions: Theory, Evidence, and PracticeFrom EverandCapital Structure and Corporate Financing Decisions: Theory, Evidence, and PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Syllabus for ENG-1B-45999 OL (06_17-07_25) Critical Thinking_WritingDocument5 pagesSyllabus for ENG-1B-45999 OL (06_17-07_25) Critical Thinking_Writingjiejialing08No ratings yet

- MARK3088 - Lecture Wk 5 - New Product Idea GenerationDocument46 pagesMARK3088 - Lecture Wk 5 - New Product Idea Generationjiejialing08No ratings yet

- e56c58ed40004cbce696d41ee0347a78apm_coursework(2)Document4 pagese56c58ed40004cbce696d41ee0347a78apm_coursework(2)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- SM ASSIGNMENT 1Document2 pagesSM ASSIGNMENT 1jiejialing08No ratings yet

- SM MIDTERM EXAMDocument2 pagesSM MIDTERM EXAMjiejialing08No ratings yet

- HIST 11 NotesDocument52 pagesHIST 11 Notesjiejialing08No ratings yet

- ACCT5919 Individual Assignment and Reflection Term 2 2024(5)Document3 pagesACCT5919 Individual Assignment and Reflection Term 2 2024(5)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- [9789004233041 - Crossing Boundaries] Crossing BoundariesDocument273 pages[9789004233041 - Crossing Boundaries] Crossing Boundariesjiejialing08No ratings yet

- MCD2080 Business Statistics Group Assignment-FinalDocument5 pagesMCD2080 Business Statistics Group Assignment-Finaljiejialing08No ratings yet

- 4a_Convolutional_Neural_NetworksDocument56 pages4a_Convolutional_Neural_Networksjiejialing08No ratings yet

- _I Need U_Document21 pages_I Need U_jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240415 125.364 Week 06 Interest rate swapDocument21 pages20240415 125.364 Week 06 Interest rate swapjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Option 1_Advertisment Design CanvasDocument2 pagesAssignment 2 Option 1_Advertisment Design Canvasjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Option 3_Store Design CanvasDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 Option 3_Store Design Canvasjiejialing08No ratings yet

- 大纲 MARK3088 Assessment Guide 2024 T2Document14 pages大纲 MARK3088 Assessment Guide 2024 T2jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240319 125.364 Week 04-05 Part 01Document25 pages20240319 125.364 Week 04-05 Part 01jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240325 125.364 Week 05Document41 pages20240325 125.364 Week 05jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240226_125.364 Week 01Document61 pages20240226_125.364 Week 01jiejialing08No ratings yet

- 20240312_125.364 Topic03Document45 pages20240312_125.364 Topic03jiejialing08No ratings yet

- Segment reporting exam question 2015 (1)Document2 pagesSegment reporting exam question 2015 (1)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- Week 8 Lecture - Sustainability and climate change reporting (2)Document32 pagesWeek 8 Lecture - Sustainability and climate change reporting (2)jiejialing08No ratings yet

- Massey Uni Sustainability reporting-Final2Document23 pagesMassey Uni Sustainability reporting-Final2jiejialing08No ratings yet

- WEEK 2 LECTURE SLIDESDocument29 pagesWEEK 2 LECTURE SLIDESjiejialing08No ratings yet

- General Concepts of IncomeDocument16 pagesGeneral Concepts of Incomejiejialing08No ratings yet

- Week 3 LECTURE SLIDESDocument53 pagesWeek 3 LECTURE SLIDESjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Income from PropertyDocument12 pagesIncome from Propertyjiejialing08No ratings yet

- WEEK 6 LECTURE SLIDESDocument46 pagesWEEK 6 LECTURE SLIDESjiejialing08No ratings yet

- IRAC MethodDocument13 pagesIRAC Methodjiejialing08No ratings yet

- Week (1) lectureDocument25 pagesWeek (1) lecturejiejialing08No ratings yet

- Babst Vs CA PDFDocument17 pagesBabst Vs CA PDFJustin YañezNo ratings yet

- SB KarbonDocument3 pagesSB KarbonAbdul KarimNo ratings yet

- Task Force On Sexual Assault and Interpersonal Violence Final Report 2014-15Document16 pagesTask Force On Sexual Assault and Interpersonal Violence Final Report 2014-15Fourth EstateNo ratings yet

- Ethnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesDocument13 pagesEthnomedical Knowledge of Plants and Healthcare Practices Among The Kalanguya Tribe in Tinoc, Ifugao, Luzon, PhilippinesJeff Bryan Arellano HimorNo ratings yet

- Major Landforms of The Earth NotesDocument3 pagesMajor Landforms of The Earth NotesSIMMA SAI PRASANNANo ratings yet

- Palaycheck System Based Rice Cultivation in The PhilippinesDocument125 pagesPalaycheck System Based Rice Cultivation in The PhilippinesRizalito BenitoNo ratings yet

- Greece Education Foundation Courses and Gces 10 2010Document6 pagesGreece Education Foundation Courses and Gces 10 2010Stamatios KarapournosNo ratings yet

- Report On Tapal by AliDocument72 pagesReport On Tapal by AliAli Xydi87% (15)

- GIDC Rajju Shroff ROFEL Institute of Management Studies: Subject:-CRVDocument7 pagesGIDC Rajju Shroff ROFEL Institute of Management Studies: Subject:-CRVIranshah MakerNo ratings yet

- Phd:304 Lab Report Advanced Mathematical Physics: Sachin Singh Rawat 16PH-06 (Department of Physics)Document12 pagesPhd:304 Lab Report Advanced Mathematical Physics: Sachin Singh Rawat 16PH-06 (Department of Physics)sachin rawatNo ratings yet

- Assignment in Research 1Document7 pagesAssignment in Research 1cpmac123No ratings yet

- Grade 2 - 1ST Periodical TestDocument5 pagesGrade 2 - 1ST Periodical TestGAY IBANEZ100% (1)

- Free Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGADocument31 pagesFree Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGAAmit AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Referee Report TemplateDocument2 pagesReferee Report TemplateAna Jufriani100% (1)

- Sports Competence ResearchDocument11 pagesSports Competence ResearchHanna Relator DolorNo ratings yet

- The Role of Green InfrastractureDocument18 pagesThe Role of Green InfrastractureYonaminos Taye WassieNo ratings yet

- Logging Best Practices Guide PDFDocument12 pagesLogging Best Practices Guide PDFbnanduriNo ratings yet

- Test Method For DDF ProjectDocument13 pagesTest Method For DDF ProjectrantosbNo ratings yet

- Whyte Human Rights and The Collateral Damage oDocument16 pagesWhyte Human Rights and The Collateral Damage ojswhy1No ratings yet

- Linkages and NetworkDocument28 pagesLinkages and NetworkJoltzen GuarticoNo ratings yet

- List Peserta Swab Antigen - 5 Juni 2021Document11 pagesList Peserta Swab Antigen - 5 Juni 2021minhyun hwangNo ratings yet

- 8 Lec 03 - Partnership Formation With BusinessDocument2 pages8 Lec 03 - Partnership Formation With BusinessNathalie GetinoNo ratings yet

- English Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesDocument18 pagesEnglish Curriculum Reforminthe PhilippinesLanping FuNo ratings yet

- Consultancy - Software DeveloperDocument2 pagesConsultancy - Software DeveloperImadeddinNo ratings yet

- Indercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDocument294 pagesIndercos2021 Fulltext Congress BookDr Sneha's Skin and Allergy Clinic IndiaNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument9 pagesReportshobhaNo ratings yet

- PYF Biennial Conference Vawi 19-NaDocument1 pagePYF Biennial Conference Vawi 19-NaMizoram Presbyterian Church SynodNo ratings yet

- Gentrification in Color and TimeDocument38 pagesGentrification in Color and TimeBNo ratings yet

![[9789004233041 - Crossing Boundaries] Crossing Boundaries](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/751444676/149x198/892bd0af3a/1721296852?v=1)