Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Compiler

Compiler

Uploaded by

Ashblue GalveOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Compiler

Compiler

Uploaded by

Ashblue GalveCopyright:

Available Formats

Joan Grace T.

Galve BSCS 42e1

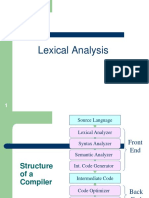

Lexical Analysis

Lexical analysis or scanning is the process where the stream of characters making up the source program is read from left-to-right and grouped into tokens. Tokens are sequences of characters with a collective meaning. There are usually only a small number of tokens for a programming language: constants (integer, double, char, string, etc.), operators (arithmetic, relational, logical), punctuation, and reserved words. Lexical Grammar The specification of a programming language will often include a set of rules which defines the lexer. These rules usually consist of regular expressions and they define the set of possible character sequences that are used to form individual tokens or lexemes. In programming languages delimiting blocks with tokens (e.g., "{" and "}") as opposed to offside rule languages delimiting blocks with indentation, white space is also defined by a regular expression and influences the recognition of other tokens but does not itself contribute tokens. White space is said to be non-significant in such languages. Token A token is a string of characters, categorized according to the rules as a symbol (e.g., IDENTIFIER, NUMBER, COMMA). The process of forming tokens from an input stream of characters is called tokenization and the lexer categorizes them according to a symbol type. A token can look like anything that is useful for processing an input text stream or text file. A lexical analyzer generally does nothing with combinations of tokens, a task left for a parser. For example, a typical lexical analyzer recognizes parentheses as tokens, but does nothing to ensure that each '(' is matched with a ')'. Consider this expression in the C Programming Language: sum=3+2; Tokenized in the following table: Lexeme Token type

sum

Identifier

Assignment operator

Number

Addition operator

Number

End of statement

Tokens are frequently defined by regular expressions, which are understood by a lexical analyzer generator such as lex. The lexical analyzer (either generated automatically by a tool like lex, or hand-crafted) reads in a stream of characters, identifies the lexemes in the stream, and categorizes them into tokens. This is called "tokenizing." If the lexer finds an invalid token, it will report an error. Following tokenizing is parsing. From there, the interpreted data may be loaded into data structures for general use, interpretation, or compiling. Scanner The first stage, the scanner, is usually based on a finite-state machine (FSM). It has encoded within it information on the possible sequences of characters that can be contained within any of the tokens it handles (individual instances of these character sequences are known as lexemes). For instance, an integer token may contain any sequence of numerical digit characters. In many cases, the first non-whitespace character can be used to deduce the kind of token that follows and subsequent input characters are then processed one at a time until reaching a character that is not in the set of characters acceptable for that token (this is known as the maximal munch rule, or longest match rule). In some languages the lexeme creation rules are more complicated and may involve backtracking over previously read characters.

Tokenizer Tokenization is the process of demarcating and possibly classifying sections of a string of input characters. The resulting tokens are then passed on to some other form of processing. The process can be considered a sub-task of parsing input. Take, for example, The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog The string isn't implicitly segmented on spaces, as an English speaker would do. The raw input, the 43 characters, must be explicitly split into the 9 tokens with a given space delimiter (i.e. matching the string " " or regular expression /\s{1}/). The tokens could be represented in XML, <sentence> <word>The</word> <word>quick</word> <word>brown</word> <word>fox</word> <word>jumps</word> <word>over</word> <word>the</word> <word>lazy</word> <word>dog</word> </sentence> Or an s-expression, (sentence ((word The) (word quick) (word brown) (word fox) (word jumps) (word over) (word the) (word lazy) (word dog))) A lexeme, however, is only a string of characters known to be of a certain kind (e.g., a string literal, a sequence of letters). In order to construct a token, the lexical analyzer needs a second stage, the evaluator, which goes over the characters of the lexeme to produce a value. The lexeme's type combined with its value is what properly constitutes a token, which can be given to a parser. (Some tokens such as parentheses do not really have values, and so the evaluator function for these can return nothing. The evaluators for integers, identifiers, and strings can be considerably more complex. Sometimes evaluators can suppress a lexeme entirely, concealing it from the parser, which is useful for whitespace and comments.) For example, in the source code of a computer program the string net_worth_future = (assets - liabilities); might be converted (with whitespace suppressed) into the lexical token stream: NAME "net_worth_future"

EQUALS OPEN_PARENTHESIS NAME "assets" MINUS NAME "liabilities" CLOSE_PARENTHESIS SEMICOLON Though it is possible and sometimes necessary, due to licensing restrictions of existing parsers or if the list of tokens is small, to write a lexer by hand, lexers are often generated by automated tools. These tools generally accept regular expressions that describe the tokens allowed in the input stream. Each regular expression is associated with a production in the lexical grammar of the programming language that evaluates the lexemes matching the regular expression. These tools may generate source code that can be compiled and executed or construct a state table for a finite-state machine (which is plugged into template code for compilation and execution). Regular expressions compactly represent patterns that the characters in lexemes might follow. For example, for an English-based language, a NAME token might be any English alphabetical character or an underscore, followed by any number of instances of any ASCII alphanumeric character or an underscore. This could be represented compactly by the string [azA-Z_][a-zA-Z_0-9]*. This means "any character a-z, A-Z or _, followed by 0 or more of a-z, AZ, _ or 0-9". Regular expressions and the finite-state machines they generate are not powerful enough to handle recursive patterns, such as "n opening parentheses, followed by a statement, followed by n closing parentheses." They are not capable of keeping count, and verifying that n is the same on both sides unless you have a finite set of permissible values for n. It takes a fullfledged parser to recognize such patterns in their full generality. A parser can push parentheses on a stack and then try to pop them off and see if the stack is empty at the end. The Lex programming tool and its compiler is designed to generate code for fast lexical analysers based on a formal description of the lexical syntax. It is not generally considered sufficient for applications with a complicated set of lexical rules and severe performance requirements; for instance, the GNU Compiler Collection (gcc) uses hand-written lexers.

You might also like

- A. S. Troelstra, H. Schwichtenberg-Basic Proof Theory-Cambridge University Press (2000) PDFDocument430 pagesA. S. Troelstra, H. Schwichtenberg-Basic Proof Theory-Cambridge University Press (2000) PDFBruno Sbrancia100% (2)

- CS3304 9 LanguageSyntax 2 PDFDocument39 pagesCS3304 9 LanguageSyntax 2 PDFrubaNo ratings yet

- Lexical AnalyzerDocument35 pagesLexical AnalyzerBrij Mohan100% (1)

- Ejercicios K. Louden Impares PDFDocument54 pagesEjercicios K. Louden Impares PDFJose Salavert MorenoNo ratings yet

- 11 17 2018 PDFDocument167 pages11 17 2018 PDFnilupul jayasekaraNo ratings yet

- Role of Lexical AnalyserDocument5 pagesRole of Lexical AnalyserIsha SankhayanNo ratings yet

- Certificate Declaration: Topic NameDocument16 pagesCertificate Declaration: Topic NameManish ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document6 pagesChapter 2Antehun asefaNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Lexical AnalyserDocument10 pagesModule 5 Lexical AnalyserJeevanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Lexical AnalyserDocument40 pagesChapter 2 - Lexical Analyserbekalu alemayehuNo ratings yet

- Compiler Design 1Document30 pagesCompiler Design 1Laptop StorageNo ratings yet

- Compiler Construction CS-4207: Lecture 4-5 Instructor Name: Atif IshaqDocument37 pagesCompiler Construction CS-4207: Lecture 4-5 Instructor Name: Atif IshaqFaisal ShehzadNo ratings yet

- Chap 11Document28 pagesChap 11stepaNo ratings yet

- Lexical Analysis: Risul Islam RaselDocument148 pagesLexical Analysis: Risul Islam RaselRisul Islam RaselNo ratings yet

- SE Compiler Chapter 2Document16 pagesSE Compiler Chapter 2mikiberhanu41No ratings yet

- Lexing and TokensDocument6 pagesLexing and TokensricardoescuderorrssNo ratings yet

- Compiler Design - Lexical AnalysisDocument2 pagesCompiler Design - Lexical Analysisswarna_793238588No ratings yet

- M.Suhaib Khalid PDFDocument10 pagesM.Suhaib Khalid PDFMohammad SuhaibNo ratings yet

- Lexical Analysis Using Jflex: TokensDocument39 pagesLexical Analysis Using Jflex: TokensCarlos MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Lexical AnalyserDocument38 pagesChapter 2 - Lexical AnalyserYitbarek MurcheNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Lexical Analysis - Part 1: Harshita SharmaDocument55 pagesUnit 2 Lexical Analysis - Part 1: Harshita SharmaVishu AasliyaNo ratings yet

- Compiler Design - Lexical Analysis: University of Salford, UKDocument1 pageCompiler Design - Lexical Analysis: University of Salford, UKAmmar MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Lexical AnalysisDocument6 pagesLexical AnalysisTuhin ChandraNo ratings yet

- Unit - 2 Lexical AnalysisDocument11 pagesUnit - 2 Lexical Analysismdumar umarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Lexical AnalyserDocument39 pagesChapter 2 - Lexical AnalyserAbrham EnjireNo ratings yet

- CSC 401 Assignment 3Document2 pagesCSC 401 Assignment 3Joko AlamuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Lexical Analysis (Scanning) EditedDocument46 pagesChapter 2 Lexical Analysis (Scanning) EditedDaniel Bido RasaNo ratings yet

- Lecture3 - Lexical AnalysisDocument153 pagesLecture3 - Lexical AnalysisMilon SheikhNo ratings yet

- 2-Lexical AnalysisDocument52 pages2-Lexical AnalysisHASNAIN JANNo ratings yet

- Lexical AnalysisDocument38 pagesLexical Analysissaeed khanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Lexical AnalyserDocument29 pagesChapter 3 Lexical AnalyserkalpanamcaNo ratings yet

- Lexical Analysis: TokensDocument1 pageLexical Analysis: TokensEr Ajay SharmaNo ratings yet

- Lexical Analysis - Compiler Design: Token, Pattern and LexemeDocument5 pagesLexical Analysis - Compiler Design: Token, Pattern and LexemehellomeranaamNo ratings yet

- Compiler 6Document28 pagesCompiler 6Tayyab FiazNo ratings yet

- CSC 318 Class NotesDocument21 pagesCSC 318 Class NotesYerumoh DanielNo ratings yet

- VMKV Engineering College Department of Computer Science & Engineering Principles of Compiler Design Unit I Part-ADocument80 pagesVMKV Engineering College Department of Computer Science & Engineering Principles of Compiler Design Unit I Part-ADular ChandranNo ratings yet

- Lexer.: Chapter Two: Lexical AnalysisDocument17 pagesLexer.: Chapter Two: Lexical Analysisኃይለ ማርያም አዲሱNo ratings yet

- Syntax WikipediaDocument2 pagesSyntax WikipediakevinNo ratings yet

- Basic Parsing TechniquesDocument34 pagesBasic Parsing TechniquesojuNo ratings yet

- Tokenising and Regular Expressions - L11Document6 pagesTokenising and Regular Expressions - L11Shilpy VermaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Lexical AnalysisDocument45 pagesChapter 2 - Lexical AnalysisAschalew AyeleNo ratings yet

- Ss Lab Viva QuestionsDocument3 pagesSs Lab Viva QuestionsCharlie Choco67% (3)

- Student Name: Tittle: Course: Second Stage: 2 Lecturer Name: D.wijdan Abdul AmeerDocument8 pagesStudent Name: Tittle: Course: Second Stage: 2 Lecturer Name: D.wijdan Abdul Ameerاسيا عكاب يوسف زغير صباحيNo ratings yet

- CD - CH2 - Lexical AnalysisDocument67 pagesCD - CH2 - Lexical AnalysisfanNo ratings yet

- Unit 2-LEXICAL ANALYSISDocument46 pagesUnit 2-LEXICAL ANALYSISBuvana MurugaNo ratings yet

- Compiler 18700220055 PrathamraiDocument12 pagesCompiler 18700220055 PrathamraiPratham RaiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document4 pagesLecture 3uzmaNo ratings yet

- Study of Lex and Yacc: LexisaDocument4 pagesStudy of Lex and Yacc: Lexisasenthilvadivu_sNo ratings yet

- LN6 - C2 - Elements of Lexical AnalysisDocument3 pagesLN6 - C2 - Elements of Lexical AnalysisMehrab Rabbi RatinNo ratings yet

- Compiler Design: Lexical AnalysisDocument68 pagesCompiler Design: Lexical Analysisshihab shoronNo ratings yet

- 2 LexicalDocument7 pages2 Lexicalyas123100% (1)

- CConsDocument6 pagesCConsAaron RNo ratings yet

- rkCD-Chapter 2 - LEXICAL ANALYSISDocument9 pagesrkCD-Chapter 2 - LEXICAL ANALYSISsale msgNo ratings yet

- Study of Lex and Yacc AimDocument4 pagesStudy of Lex and Yacc Aimpinkupriya17No ratings yet

- CD KCS502 Unit 1 BDocument12 pagesCD KCS502 Unit 1 Bshivendrasingh43613No ratings yet

- Unit 01 - PART 2Document25 pagesUnit 01 - PART 2harishkarnan004No ratings yet

- Parsing PDFDocument5 pagesParsing PDFfiraszekiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Scanning: 3.1 Kinds of TokensDocument17 pagesChapter 3 - Scanning: 3.1 Kinds of TokenslikufaneleNo ratings yet

- CD Unit-2Document64 pagesCD Unit-2dartionjpNo ratings yet

- Compiler ConstructionDocument14 pagesCompiler ConstructionMa¡RNo ratings yet

- Automata Theory and Compiler Design: Name: Smitha.A Usn: 1Vj21Cs042 Branch: CseDocument9 pagesAutomata Theory and Compiler Design: Name: Smitha.A Usn: 1Vj21Cs042 Branch: CseSmitha.A Smitha.ANo ratings yet

- SettingsproviderDocument29 pagesSettingsproviderJoão PedroNo ratings yet

- CH 5-Part 1Document31 pagesCH 5-Part 1Ch Zaid RazaNo ratings yet

- CD QuestionBankDocument12 pagesCD QuestionBankDhrûv VâñpärîåNo ratings yet

- Syntax Directed TranslationDocument30 pagesSyntax Directed Translationতানভীর তাঈনNo ratings yet

- Assignment # 2Document5 pagesAssignment # 2Muhammad Ahmad KhanNo ratings yet

- Topic 4-Bv2Document77 pagesTopic 4-Bv2hooranghooraeNo ratings yet

- Restricting and Sorting DataDocument24 pagesRestricting and Sorting DataaaaaNo ratings yet

- Ways To Specify Semantics: - by A Language Reference ManualDocument41 pagesWays To Specify Semantics: - by A Language Reference Manualgautham_atluriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9: Turing Machine: The Standard Turing Machine Page: 336-338, 20 ProblemDocument12 pagesChapter 9: Turing Machine: The Standard Turing Machine Page: 336-338, 20 ProblemkachuloNo ratings yet

- Driver L6470 Pentru Motoare Pas Cu Pas Electrice1 PDFDocument10 pagesDriver L6470 Pentru Motoare Pas Cu Pas Electrice1 PDFAlice IoanaNo ratings yet

- Sample DepEd Mathematics Class RecordDocument22 pagesSample DepEd Mathematics Class RecordDexter Martije Descotido50% (2)

- Regex in C#Document3 pagesRegex in C#Bhavya KambojNo ratings yet

- CS110T Lab02 PDFDocument6 pagesCS110T Lab02 PDFmNo ratings yet

- 2-Re or RL To FaDocument7 pages2-Re or RL To FaMD.MAZEDUL ISLAMNo ratings yet

- Module 2 MATHEMATICAL LANGUAGE AND SYMBOLSDocument63 pagesModule 2 MATHEMATICAL LANGUAGE AND SYMBOLShgfhfghfghg63% (8)

- SS 0slab 15csl67Document63 pagesSS 0slab 15csl67TalibNo ratings yet

- Compiler Lab (2016-2017)Document63 pagesCompiler Lab (2016-2017)HARIPRIYANo ratings yet

- Programming 1 Python ArraysDocument56 pagesProgramming 1 Python Arraysj mNo ratings yet

- CS602PC - Compiler Design Lecture Notes Unit 2Document42 pagesCS602PC - Compiler Design Lecture Notes Unit 2Senthil Kumar SkumarNo ratings yet

- RakudoDocument17 pagesRakudoscrubbydooNo ratings yet

- Week1 Discrete Math PDFDocument12 pagesWeek1 Discrete Math PDFjymrprzbtstNo ratings yet

- Arrays (Java Tutorial)Document29 pagesArrays (Java Tutorial)AmihanNo ratings yet

- Characters StringsDocument33 pagesCharacters StringsKarthic SundaramNo ratings yet

- Digital Electronics Tutorial Sheet-2Document2 pagesDigital Electronics Tutorial Sheet-2Alok PandeyNo ratings yet

- Theory of Computation - Part - A - Anna University QuestionsDocument8 pagesTheory of Computation - Part - A - Anna University Questionsbhuvangates0% (1)

- MAE 434: Modern Control, Fall 2015Document2 pagesMAE 434: Modern Control, Fall 2015akiscribd1No ratings yet

- Structures in C RecapDocument8 pagesStructures in C RecapVeena S.TNo ratings yet