Professional Documents

Culture Documents

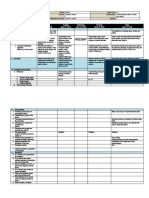

Records of Sole or Single Proprietorship

Records of Sole or Single Proprietorship

Uploaded by

Krizia CabangOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Records of Sole or Single Proprietorship

Records of Sole or Single Proprietorship

Uploaded by

Krizia CabangCopyright:

Available Formats

Records of sole or single proprietorship

Equity is the difference between assets and liabilities as shown on a balance sheet. In other words, equity represents the portion of assets that are fully owned by the owners (stockholders, partners, or proprietor) of a business. When I prepare financial statements, I always review the general ledger (GL) account numbers that the client has coded on the check register. Whenever I see a balance sheet GL account number, I automatically double-check it. The reason I do this is that the balance sheet is the least understood part of the financial statements for most clients. This is especially true regarding the equity section. In a way, this is rather strange, since the equity section represents the owners share of the business. I would want to keep a very close eye on my investment and, to do that effectively, I would need to know the nature of each equity account and how to interpret the changes in those accounts as they occur. If I am a sole proprietor, its not as crucial because everything in the equity section is mine. Thats not to diminish the importance of knowing what the accounts mean, as there are other good reasons to track the increases and decreases that occur within them. However, if I am a partner in a partnership or a stockholder in a corporation, it is my responsibility to protect my investment interest from mistakes and/or deliberate misstatements. This can be a challenge and accounting knowledge is required. It is in this light that I thought a review of the equity accounts for a sole proprietor, partnership, and corporation could prove useful. In order to do this, you need to understand how debits and credits work. If you need a reminder, you can click on this link: http://www.reallifeaccounting.com/accounting_model.aspand print out a copy of the Accounting Model for a guide. SOLE PROPRIETOR The equity section title in a sole proprietorship is most commonly called Owners Equity. The accounts within this section are usually laid out in this fashion: Owners Equity Current Year Capital Contributions Owners Draw Net Profit or Loss Look at the accounting model chart and find the equity section. An increase to the equity section requires a credit entry, while a decrease requires a debit entry. Following this accounting logic, it makes sense that a contribution of personal money to the business requires a debit entry to Cash and a credit entry to Current Year Capital Contributions. On the other hand, if cash is removed from the business for personal reasons, a debit entry to Owners Draw and a credit entry to Cash would be required. Furthermore, if the business showed a profit, that would indicate an increase in equity (credit), or if it showed a loss, that would indicate a decrease (debit) in equity.

Since the Owners Equity account (a credit balance account) is an accumulation account, all the other accounts are closed out at the end of the year into the Owners Equity account. This makes perfect sense when you follow the journal entries required to close out the accounts. For Instance: Net Profit or Loss is automatically closed into Owners Equity at the end of the year by your computer. If a journal entry were written, it would look like this: DESCRIPTION Net Profit Owners Equity DEBIT 50,000 50,000 CREDIT

Or DESCRIPTION Owners Equity Net Loss DESCRIPTION Owners Equity Owners Draw DESCRIPTION Captial Contribution Owners Equity DEBIT 2,000 2,000 DEBIT 20,000 20,000 CREDIT CREDIT DEBIT 5,000 5,000 CREDIT

As you can see the function of the sole proprietor equity accounts is not complicated or difficult to understand. PARTNERSHIP Depending on how many partners there are, partnership equity accounts usually are organized as follows under the title, Partners Equity: Partner A, Capital Account Partner B, Capital Account Partner C. Capital Account Net Profit or Loss

All the increases or decreases occur within the partners capital accounts. In other words, the partner capital accounts are the equity accounts. If a partner makes a capital contribution, then his/her capital account is increased (credit). If the partner takes a distribution, then the capital account is decreased (debit). If the business has a profit or a loss at the end of the year, then that profit or loss is distributed among the partners at whatever ownership interest or other arrangement is appropriate. General partners who work in the business are paid a management fee called a guaranteed payment. This fee is a legitimate business expense and therefore acts to lower the net profit of the business. This fee is similar to a salary paid to a working stockholder in a corporation, except, according to U.S. tax law, a fee paid to a working partner cannot be run through payroll. It is treated as a draw, subject to self-employment taxes. Both the general partners guaranteed payment and share of the profits are taxable and subject to self-employment taxes. Sometimes a business may not have enough cash to make a distribution to the partners even though the business realized a profit. Partners may have a rude awakening to discover that they still have to pay taxes on those profits regardless of whether they received any money. Another scenario to be aware of if you are a non-working general partner or a limited partner is this one: You and your partner contributed an equal amount of cash for working capital. The reason for investing your money is because you expect to share in the profits. Your partner is a working partner and is entitled to receive a management fee for services rendered. You need to keep an eye on the books because there may never be a profit to share in if your partner simply continues to increase his/her management fee. It can be a sticky situation because the working partner may feel he/she is never making enough money to justify all the work he/she has to do. It is best to define what the management fee is going to be in the partnership agreement beforehand. CORPORATION (Primarily closely held corporations) Closely held (private) corporation equity accounts are a little more complicated than a sole proprietorship or partnership. These are the typical accounts found in the corporation equity section under the title, Stockholders Equity: Retained Earnings Paid-in-Capital Dividends Paid Common and/or Preferred Stock Net Profit or Loss Retained Earnings is similar to the Owners Equity account in that the Net Profit or Loss is closed into that account at the end of each accounting year. Paid-in-Capital is the account used to record capital contributions made by stockholders. Keep in mind, as in the examples above, that increases to an equity account are credits. For example: DESCRIPTION DEBIT CREDIT

Cash Paid-in-Capital

5,000 5,000

If dividends were paid the journal entry would look like this: DESCRIPTION Dividends Paid Cash DEBIT 10,000 10,000 CREDIT

When common stock is sold or issued to raise money or acquire property: DESCRIPTION Cash Common Stock DEBIT 100,000 100,000 CREDIT

When Net Profit is closed out for the year: DESCRIPTION Net Profit Retained Earnings DEBIT 20,000 20,000 CREDIT

These accounts are also found on public corporations, however they may have additional equity accounts that are necessary to explain more complex activities. You can see that the equity accounts in all three business entities function in a similar manner. From year to year, there should be continuity. This means there should be a logical explanation for any increases or decreases in theequity accounts. As an investor or owner, you have a right to know the reasons for any changes. If there has been a mistake, willful or otherwise, it is most likely going to show up in the equity section. Stay vigilant and protect your investment. WORKING WITH THE EQUITY SECTION OF YOUR BALANCE SHEET As I say in my newly posted article, Equity Accounts Its Your Money, the equity section of the balance sheet is the least understood. I give examples of the general ledger accounts that are found in the equity section for a sole proprietor, partnership, and corporation along with an explanation of how the accounts function.

The key to understanding these accounts is having a working knowledge of how debits and credits are recorded depending on whether a transaction calls for an increase or a decrease. Use the Accounting Model link in the article if you need bruising up. For example, if you are a sole proprietor and you take money out of your business for personal purposes then you would record an entry on the debit side of the general ledger account Owners Draw. Increases to Equity require a credit entry, while decreases to Equity require a debit entry. In the example, if you wrote yourself a check you would be decreasing Cash, which is an asset. Since you wrote the check to yourself, it makes sense that you decreased your Equity. Here is the tricky part and why you need to think out what you are doing using the Accounting Model: You decreased your Equity by making a debit entry to Owners Draw and you decreased cash in your bank account when you withdrew money for personal reasons and made a credit entry to CASH. Seems straightforward doesnt it? But you increased the Owners Draw account while at the same time decreasing your equity. Sometimes this concept is hard for people to grasp. You just have to remember that Owners Draw is a general ledger account found within the Equity Section. It is useful to remember the fundamental accounting equation: ASSETS = LIABILITIES + EQUITY When Cash, an asset, was decreased then either Liabilities or Equity would also have to be decreased in order to stay in balance. In this case, the decrease was in Equity. The rule is that in any transaction recorded the DEBIT SIDE MUST EQUAL THE CREDIT SIDE of the ledger. Any questions?

T-ACCOUNTS: A GREAT TOOL FOR SOLVING ACCOUNTING TRANSACTIONS

T-ACCOUNT DEFINED A T-Account is a template or format shaped like a T that represents a particular general ledger account. Debit entries are recorded on the left side

of the T and credit entries are recorded on the right side of the T. It is a tool for organizing journal entries and analyzing accounting transactions. WORKING WITH T-ACCOUNTS There are a few business owners or managers who have a fantastic ability to remember details, but I would venture to say that most of us find our memory diminishing over time.

T-Accounts come in handy when a series of journal entries are required and it becomes too difficult to keep all of them in your head. When solving accounting problems, you have to think of accounting transactions in terms of the accounting model. Click this link if you need to refresh your memory regarding the accounting model: http://www.reallifeaccounting.com/accounting_model.asp The accounting model is a template you can use to remember how debits and credits work. The two most common scenarios for using T-Accounts are: 1) determining why certain transactions were previously posted to the general ledger; or, 2) working out the most appropriate place to post certain accounting transactions. T-Accounts work because they are visually effective. This means they are simple to understand and usually it is possible to portray all the T-Accounts on one page. Lets look at a basic accounting transaction and then translate it into T-Account form. Assume you sold an accessory to one of your rental inventory assets for $35 cash and deposited the money into the bank. You originally bought the accessory for $20 and put it into inventory until it was sold. The journal entries for the transaction would look like this: DESCRIPTION Cash Sales DESCRIPTION Cost of Goods Sold Inventory The T-Accounts would look like this: Cash 35.00 Sales 35.00 Cost of Goods Sold 20.00 DEBIT 20.00 20.00 DEBIT 35.00 35.00 CREDIT CREDIT

Inventory 20.00 You can easily see that the debits equal the credits. Lets look at a more complex accounting transaction. You bought a company van to delivery your rental inventory for $25,000 and you did this by putting $5,000 down and setting up a liability (Notes Payable) for $20,000. You made your first payment of $380, of which $80 was interest, and your first months depreciation was $833. To the unfamiliar, these transactions might appear confusing until T-Accounts are used. Fixed Assets Van 25,000 Cash 5,000 Notes Payable 20,000 Notes Payable 300 Interest Expense 80 Cash 380 Depreciation Expense 833 Accumulated Depreciation 833

A critical step is to make sure that the debits equal the credits. If not, you have made a mistake that must be solved. Next, simply put these T-Accounts in journal entry form: DESCRIPTION Fixed Assets Van DEBIT 25,000 CREDIT

Cash Notes Payable DESCRIPTION Notes Payable Interest Expense Cash DEBIT 300 80

5,000 20,000 CREDIT

380

INTERNAL CONTROL: A PREVENTIVE MAINENTANCE PROGRAM

You read about this in every newspaper in every town in the entire country: Some bookkeeper, trusted by the owner of a small business, embezzles thousands of dollars. If the theft doesnt put owner out of business, it certainly causes a major headache. The reason we hear of these cases so often is that, in a small business, theremay only be the owner and a bookkeeper. The owner doesnt like doing the books, doesnt understand them, and relies on this one person to take care of things. The bookkeeper, who is usually having personal financial difficulties, takes a small amount of money intending to pay it back. No one seems to notice, so more is taken. Over a period of time, it starts to mount up to a lot of money. This is where the concept of internal control comes in. Essentially, every business should have, at some level, an internal control system in place to protect against losses, both intentional and unintentional. This is because internal control systems will: 1) protect cash and other assets; 2) promote efficiency in processing transactions; and, 3) ensure reliability of financial records. An internal control system consists primarily of policies and procedures designed to provide reasonable assurance that these three objectives will be achieved. The size and complexity of the business will determine the extent of the internal control system. Regardless of size, one of the most important aspects of an internal control system is the concept of separation of duties. Separating duties makes it more difficult for theft and errors to go undetected. It is highly unusual for two employees to collude in an effort to steal from the company. I worked as an internal auditor for a newspaper chain for three years. My job was to walk in to the newspaper offices unannounced and go directly to the cash boxes, count them, and verify receipts. One of my most important audit steps was to make sure the internal control procedures were in place and working properly. Here are a few suggestions for internal control procedures regarding handling of cash:

Allow only specific designated individuals to handle cash. Give responsibility for bookkeeping to an individual who does not handle cash. Use numbered receipts to document all payments. Make all bank deposits promptly. The person who prepares the bank reconciliation should be different than the one handling cash. If possible, the person who makes the bank deposit should be different than the one who handles the cash and the one who prepares the bank reconciliation. Make deposits intact with no amounts withdrawn to pay expenses. Keep cash and checkbook in a locked drawer or cash register. Since tills will never be 100% correct all the time, establish a tolerance level for overages and shortages to determine the point at which corrective measures will be triggered. Make all disbursements by check, except minimal amounts paid from petty cash. Make certain every payment is related to a paper document, such as a voucher, to ensure that a paper trail exists for all disbursements. Conduct random surprise counts of petty cash and cash drawers. Count inventory and other assets frequently and compare with company books.

An internal control system set up early as a preventative measure is more efficient than establishing a corrective system in reaction to a loss. If it so happens, that there is just you and the bookkeeper in your small business, you need to learn how to do some of the bookkeeping tasks so you can spot check the bookkeepers work. That, in itself, is an excellent preventative measure.

VALUING GOODWILL: AVOID BUYING A PIG-IN-A-POKE

All my life I had heard the warning never to buy a pig-in-a-poke. I understood the gist of it but didnt really know what a poke was. So I looked it up one day and found out a poke was a bag. The saying refers to a scam in the late Middle Ages, at a time when good meat was scarce. If you bought a suckling pig in a bag without first looking at it, you might be surprised to find a scrawny cat jump out when you later opened it. In fact, thats where the saying, Let the cat out of the bag, came from in other words, finding out what was really in the bag. Having worked in the field of accounting for twenty-five years, I have had ample opportunity to observe, first hand, many a client who has bought a business-in-a-poke. In the old days, there were no accepted valuation formulas available to determine a reasonable price for a business. As a result, rule-of-thumb methods were used, but often had no correlation to the real worth of a business. Choosing the correct valuation formula and applying it properly can be a daunting task and should be left to the auspices of an experienced professional. However, you can become familiar with the general guidelines of a widely used business valuation formula that will, at a minimum, give you an idea of whats involved. Armed with this information, hopefully you can avoid being scammed into buying a business-in-a-poke.

Have you ever tried to sell or buy a business? Its not exactly a straightforward, easy thing to do. Most likely, if you are the seller, you will want to get top dollar for your business. After all, you worked hard to make your business work and would like to be amply compensated. Often, small business owners have a feeling for what they think the business is worth. When asked to justify the selling price, you may hear all kinds of stories. For example, one of the most common reasons sellers give for their asking price is the potential of the business. This is sometimes better known as blue sky or pie in the sky. There is no way to accurately estimate this feeling for potential, yet sellers will tell you that if you buy their business you will be in a great position when this new technology arrives, or this big store moves in next door, or if you are willing to work extra hours, and on and on. Another story you will hear is how much money the owner takes out of the business including salary and perks. Somehow the seller is equating compensation from work performed in the business to earnings. This may impress you if you are looking to buy a job. But even then, you need to pay only what the business is worth. So what do you have to do to determine the true value of a business? Rest assured that the process of valuing a business can be exceedingly complex. Much depends on the size and nature of the business you are buying or selling. The variables can seem unending. An essential element of valuing a business is determining whether Goodwill exists, and if so, what price to put on it. WHAT EXACTLY IS GOODWILL? Goodwill is the difference between the value of a business enterprise as a whole and the sum of the current fair values of its identifiable tangible and intangible net assets. Net assets are the assets that are left after subtracting the companys liabilities. Goodwill is only recorded when its amount is substantiated by an arms-length transaction. Goodwill cannot be sold or acquired separately but has to be included in a purchase with the net assets of a business enterprise. HOW IS GOODWILL VALUED? Lets say someone is selling a small business and is asking $100,000. The first question to ask is, What exactly is he/she selling? What assets are you going to receive in the deal and what, precisely, is their fair market value? After appraising the assets, are they worth $100,000? If not, the difference is what the seller construes to be Goodwill. For our hypothetical example, lets assume the net assets have a fair market value of $60,000. This means the seller wants $40,000 for Goodwill. Is this reasonable? Here are some general steps you can follow to find out: First, determine what a reasonable rate of return on an investment of $60,000 should be. (Determining this rate of return can be complex and probably requires the help of a professional.) For our purposes, lets use 8%. $60,000 x .08 = $4,800

This is the amount of normal earnings the company should be making each year. Second, determine from an average of five years of financial statements, backed up by tax returns, what the net profit is. Be sure to normalize the earnings, which is to say, remove expense items, such as depreciation and owners perks, or add in a managers salary if the owner worked in the business and didnt record a salary. Add or subtract any other appropriate items to arrive at a realistic net profit. Lets say the normalized earnings turned out to be $10,000. Third, subtract the normal earnings of $4,800 from the normalized earnings of $10,000 to determine excess earnings. $10,000 $4,800 = $5,200 Fourth, determine a capitalization rate (cap rate). This also can be complex to develop. However, the idea behind a cap rate is this: The lower the risk, the lower the return on investment. The higher the risk, the higher the return on investment. For example, if you invest your money in your local bank, the risk of losing your investment is relatively low. Therefore, you only earn about 2%. Invest in the stock market and you can expect to earn up to 10% or higher in some cases, because it is a more risky investment. A small business can be a very risky investment, and a rule of thumb says you should at least expect to earn 20%. But, if the small business has factors that indicate less stability, then an even higher rate of return should be expected, perhaps 30% or 40%. Determining an appropriate and accurate cap rate is probably the hardest part of valuing a business. However, lets say our cap rate is 20%. Fifth, divide the cap rate into the excess earnings to determine Goodwill. $5,200 / 20% = $26,000 Sixth, add the net assets value and the Goodwill to determine the full value of the business. $60,000 + $26,000 = $86,000 Our seller wanted $100,000 for the business. Now you can go to him and say, Gee, I just dont see it that way, take a look at my analysis. Usually, the seller will back down when presented with a formula approach. If the seller hires his own accountant to provide a formula approach and his value of the business is higher than yours, (you can bet on it) then a common approach is to settle on a price that is the difference between the two. How could the sellers accountant come up with a different figure than yours? Its in those rates and all the variables that go into developing them. It doesnt take much to skew the percentage points one way or another. Here is a what if: What if the sellers accountant came up with a rate of return for net assets of 6% instead of 8%?

$60,000 x .06 = $3,600 Normal earnings $10,000 $3,600 = $6,400 Excess earnings And, what if the sellers accountant came up with a cap rate of 18% instead of 20%? $6,400 / .18 = $35,556 $60,000 + $35,556 = $95,556 This is very close to the sellers original asking price of $100,000. The name of this formula of valuing a business is called the Net Assets plus Excess Earnings method. It does not work on all businesses and there are other methods that can be used. The main point is to inform you that formulae do exist and not simply to accept the rationalizations of the seller. DOES GOODWILL EVEN EXIST? This is a quick and dirty method to see if you want to waste your time negotiating a business offering. When the seller provides financial statements for your perusal, look at the bottom line. Take the time to normalize the earnings as mentioned above. Is there a profit? If not, you know there is not going to be any goodwill. What are the assets worth that you will be buying? Are they less than the asking price? If so, you can pretty much bank on the fact that the asking price is too high. Look at alternatives. Could you buy new assets for the amount the seller is asking and start your own business from scratch? Why pay for something that doesnt exist? WHAT HAPPENS IF THE SELLER HAS TWO SETS OF BOOKS? Business owners who keep two sets of books are not altogether uncommon. They keep one set of books for the government and another set for internal purposes. There is nothing wrong with this practice unless it is for the purpose of hiding income in order to pay lower taxes. The problem for these people arises when it comes time to sell their business. They want you (the buyer) to accept their internal books because they reflect more profit. However, you have no way of verifying that these books are accurate. That is why it is important to make sure that the tax returns of the business support the financial statements. Business owners who follow this practice of deception want it both ways. What they dont realize is that any wise and astute buyer is not going to go along with it. If a business owner is going to lie and cheat the government, surely that person is capable of lying to a potential buyer. My recommendation is to walk away or only pay a price based on information from the tax return. GOOD FINANCIAL RECORDS If you are buying or selling your business, good records are a must. Buyers are going to want an historical average of profits so they can develop trends. Trends speak volumes. Good financial records are indicators of how the business was managed. A strong

prospective buyer will expect nothing less than Balance Sheets and Profit and Loss Statements that tie directly to the business tax returns. Ive witnessed solid buyers walking away from deals because of sloppy books. Sloppy books are a pig-in-a-poke to a prudent buyer.

RECORDING GOODWILL ON THE BOOKS

Have you ever seen Goodwill as an asset category on a set of financial statements? Do you wonder how the dollar amount was arrived at? Did you know that the only way Goodwill can be entered on the balance sheet is through a purchase? For a definition and general understanding of Goodwill, be sure to read my blog article titled, Valuing Goodwill: Avoid buying a Pig-in-a-Poke. Lets assume youve done that and you now know that Goodwill is the difference between the value of a business enterprise as a whole and the sum of the current fair values of its identifiable tangible and intangible net assets. Lets also assume that you have just purchased a sole proprietorship small business for $150,000. You paid for it by making a down payment of $50,000 from personal funds and acquired a bank loan for the remaining $100,000. The purchase consists of $70,000 in Fixed Assets, and $80,000 in Goodwill. The journal entry would be: ACCOUNT DEBIT CREDIT Fixed Assets $70,000 Goodwill $80,000 Notes Payable $100,000 Capital Contributions $ 50,000 You know you can depreciate the Fixed Assets, but can you write off Goodwill? According to the Internal Revenue Service, under the MACRS system, Goodwill can be amortized over a fifteen year period. If you bought the business on July 1, the first years amortization would be $2,666.67. Each full year would be $5,333.33. Simply divide $80,000 by 15 to get $5,333.33. Divide that amount by 2 to arrive at $2,666.67. Depending on what month of the year you purchased the business determines the amount amortization expense. The journal entry to record amortization for Goodwill would look like this: ACCOUNT DEBIT CREDIT Amortization Expense $2,666.67 Accumulated Amortization $2,666.67

Pretty straightforward, wouldnt you say?

Filed in John's Comments | | Comments (2)

THE HISTORICAL COST CONCEPT ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLE

03-OCT-05 Imagine, for a moment, trying to read a financial statement that had listed assets such as: cash $5,000; 14 boxes of oranges; 25 boxes of apples; 1000 board feet of lumber; 3 acres of land; and, 8 machines. A first question that might pop into your mind is: How in the world do I add these assets to one another? It is immediately clear that for financial statements to be meaningful, amounts of dissimilar items must be stated in similar units. Money becomes the obvious choice of similar units. By converting different kinds of objects into monetary amounts, they can be dealt with arithmetically. This is called the money-measurement concept and is a fundamental principle of accounting. This is great, but the problem is not yet solved. An asset may be recorded in dollars and cents (or whatever currency is appropriate for the country in which you live), but at what value? If I were allowed to choose the value I thought was appropriate for my assets, my tendency would be to state their value at the highest amount possible. That way, my financial statement would indicate that my business was strong, healthy, and worth a lot of money. Remember the accounting equation: ASSETS LIABILITIES = EQUITY Higher assets mean higher equity. Wonderful, but what if Im wrong? My banker and my investors are trusting that my financial statements are stated accurately. Furthermore, it is not reasonable to expect that every reader of my financial statements can or should have to appraise my assets. In order to avoid the subjectivity of market value, an objective way of valuing assets had to be established. This was solved by using the historical cost concept. This concept states that the numbers reported on accounting financial statements shall be recorded at the amount that was actually paid for an asset, i.e., historical cost. Therefore, accounting does not record what an asset is actually worth, that is, its market value. This works out okay because most businesses are using their assets to conduct operations and are not trying to sell them. When a business offers an asset for sale, or perhaps the entire business, an appraisal to determine fair-market-value of the assets must be performed. So we (preparers of financial statements) are going to use money as a measurement system and we will record our assets at the amount actually paid for them. This will keep us out of trouble and make it easier to understand what others are doing. Filed in Accounting Principles | | Comments (3)

HOW TO RECORD CONTRIBUTED LABOR ON THE COMPANY BOOKS.

03-OCT-05 Clients ask me this question from time to time and usually dont like or understand the answer. The question is, If I donate or contribute my labor to a charitable institution, can I record the cost, at my normal charge rate, as an expense on my financial statement? The obvious result is that the clients Net Profit will be lower leading to lower taxes. It seems reasonable doesnt it? After all, your time is worth money and you are giving it to a worthy cause. Whats the matter with that? First, read my October article titled, The Historical Cost Concept Accounting Principle. It explains that money must exchange hands, or a promise to pay money, before an amount can be recorded on the books because there needs to be an objective way to determine the value of a transaction. Was there any money or promise of money exchanged in the example? No, there was only a contribution of labor. Second, from a debits and credits perspective, how would you record a contribution of labor? If you recorded a debit to an expense account called Contributions, what would be the credit entry? Not Cash. Not Payables. Maybe Equity? Lets look at that. If you write a credit entry to increase Equity, then the expense entry lowers Net Profit as washes out the increase in Equity. Sound pretty good? Not really, because you just violated the accounting principle of Historical Cost. No money was actually paid, so there was no objective way to value the transaction. What if you decided that your time was worth $1000 an hour? You worked eight hours so you recorded an expense of $8,000. That might be a big hit on the old Net Profit. Plus, it looks like you contributed a substantial amount to the business. More likely, someone who charged $75 an hour might be inclined to up it to $125 an hour if they felt they could. You can see why the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) would take a dim view of this. If left up to the discretion of millions of taxpayers the potential for abuse would be staggering. Therefore, this practice is not allowed. The integrity of financial statement reporting must be protected, and the IRS doesnt want to be cheated. After explaining all this to clients, often they still dont get it. Or, they dont want to get it. They feel they gave up something so they should get something back, i.e., the write off. The IRS says that if you performed a service for someone then record that service as income on your books, then you can deduct it as a legitimate Contribution expense. I say, why bother, since they both wash each other out. Its just extra accounting work. I welcome your comments or questions on this sometimes confusing concept. Filed in John's Comments | | Comments (0)

LOANS VS. LEASES: WHATS IT ALL ABOUT?

16-AUG-05

One of the most frequent questions I get asked is Shall I lease or buy? Most likely the lease vs. buy choice for a business would arise when considering the acquisition of a company automobile or delivery truck, but it could be any expensive piece of equipment. This decision is usually predicated by the desire to obtain the highest deduction or tax savings. The first step in answering the lease or buy question is to clarify the difference between these two purchasing options. BUY When you buy an item you either pay cash for it all at once, or, you sign an agreement, called a promissory note, to pay for it over time. When you buy and make installment payments, you are considered to have entered into a contract of sale. From an accounting and tax standpoint, you have purchased an asset and incurred a liability. The asset cost is deducted over a period of time through an expense category called depreciation. Usually, a down payment of a certain amount is required to consummate the purchase. Note how this transaction is set up on the books using the following journal entry: DESCRIPTION Fixed Assets Notes Payable Cash DESCRIPTION Depreciation Expense Accumulated Depr DEBIT 2,000 2,000 DEBIT 10,000 7,500 2,500 CREDIT CREDIT

When payments are made on the note there are two components to consider, i.e., principal and interest. Principal is the original amount borrowed and interest is the cost of borrowing the money. Since interest is a cost, it is a deductible expense and has its own category. For instance: DESCRIPTION Notes Payable Interest Expense Cash DEBIT 500 50 550 CREDIT

Do you see that in a contract of sale the expense deduction comes from two sources, depreciation and interest? LEASE A lease is an agreement under which the owner of property permits someone else to use it for a fee. The owner is the lessor and the user is the lessee. There are two types of leases from the standpoint of the lessee: a dirty lease and a true lease. The dirty lease is called a capital lease or a lease obligation in accounting circles, and, a true lease is called an operating lease. A CAPITAL LEASE is one in which the rights and risks of ownership of the property will be transferred to the lessee. Therefore, the lessee must evaluate the provisions of a lease in order to determine if the lease should be classified as a capital lease or an operating lease. How does the lessee do this? This is the tough part. There are four criteria to use and, if any one of them fit, the lease should be treated as a capital lease: 1. The lease transfers ownership of the property to the lessee by the end of the lease term. 2. The lease contains a bargain purchase option (like a $1.00 buyout). 3. The lease term is equal to 75% or more of the estimated economic life of the leased property. 4. The present value of the minimum lease payments, at the beginning of the lease term, is at least equal to 90% of the fair value of the leased property. I recognize that at this point I may have left many of you scratching your heads. But, dont give up just yet. Look, most of the lease contracts you are going to enter into contain the first two criteria. If the lease contracts do, dont worry about the last two criteria. If they dont and the lease doesnt appear to have the characteristics of an operating lease (see below), then you should check with your accountant to make sure you are giving the lease proper accounting treatment. In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) feel that a capital lease type of contract is so similar to a contract of sale that it should be given the same accounting and tax treatment as a normal purchase. The cost of leasing is built into the lease payment but is not stated separately (like interest on a note). However, the IRS considers it to be the same. Therefore, a Capital Lease is set up the same as a Notes Payable. DESCRIPTION Asset DEBIT 10,000 CREDIT

Capital Lease Cash

8,900 1,100

Note here that the cash down payment is less than the contract of sale above. This is one advantage of buying through a lease. Normally, the down payment includes only the first and last payment of the lease ($550 + $550 = $1,100). Depreciation occurs just as in a contract of sale. DESCRIPTION Depreciation Accumulated Deprec DEBIT 2,000 2,000 CREDIT

Often you will find that the leasing company does not give you the actual cost of the asset you are buying. What they will do is give you the total cost of the lease. For instance, if your lease payments are $550 per month for twenty months then the total lease contract will be stated as $11,000. You must remember to find out the actual value of the asset ($10,000) in order to record it accurately on your balance sheet and depreciation schedule. The rule is that the cost of the asset can never exceed its fair market value. There may be other costs called executory costs included in the lease payments. These are items such as insurance, maintenance, and property tax. These items can be expensed in each payment as they are incurred. DESCRIPTION Capital Lease Interest Expense Executory Costs Cash DEBIT 500 45 5 550 CREDIT

The $550 lease payment is split up in the same manner as the principal and interest payment of the notes payable except that you may have to include the executory costs. The only difference between a Capital Lease and a Contract of Sale purchase is that the down payment on the lease may be less. The deductible expense is the same.

An OPERATING LEASE (or true lease) is one in which the lessor retains the rights and risks of ownership. The lessee is simply obtaining the right to use the property for the term of the lease and no more. If the four criteria above are not met then the lessee should treat the lease as an operating lease. If, at the end of the term of an operating lease, you decide to keep the property, then, technically you should be required to pay the fair market value of the item at that time. However, many lessors offer the leased property at 10% of its original fair market value. This practice of using a 10% buyout at the end of the lease term does not constitute a bargain purchase option. In addition, the bookkeeping is simpler, because the full cost of the lease payments is treated as a rent expense each month. There is no asset recorded on the books, no Capital Lease Payable or Interest Expense. Here is how the journal entry looks each month: DESCRIPTION Equip Lease Expense Cash DEBIT 550 550 CREDIT

Unless you can write off the equipment all in one year using the IRS 179 Election, you can probably expense this property faster than a contract of sale which uses depreciation and interest. In twelve months, using my example, you could deduct $6,600 ($550 x 12 mo = $6,600) assuming you bought the property on January 1. What about automobile leasing vs. buying? This is a whole different ball game. The politicians have tinkered with the auto deduction over the years and made it very complicated. However, the bottom line in the U.S. is: There are statutory limitations as to how much you can depreciate an automobile in one year, depending on the cost of the auto and when you bought it. If you lease an auto, there may be an advantage; however, it depends on the lease terms. You can write off the payments (modified by the business use percentage) each month, which could very well exceed the allowable depreciation amounts. In an effort to find parity between the lease payments and the allowable depreciation amounts, the IRS constructed Lease Inclusion Tables. The idea is to modify the amount of the deductible lease payments by the amount found in the Lease Inclusion Tables. However, the amount you have to include from these tables is astoundingly small. Understandably, no one is complaining about the higher write off. CALCULATION Now that you have a sense for the accounting theory of leases and loans, your next step will be to calculate the numbers associated with the equipment in mind. The Internet has many Lease or Buy calculators. For instance, http://www.lease-vs-buy.com will take you through the process step-by-step and provide explanations and definitions for unfamiliar terms. If you dont like this one, just put lease or buy calculator in Google and pick one you do

like. Once you are finished, its probably a good idea to check your results with an accounting professional.

LEASE OR BUY: HOW THE ACCOUNTING WORKS

A description of how the accounting works for a contract of sale purchase, a capital lease, and an operating lease can be found in my article Loans vs. Leases: Whats it all about? But to give you an idea of what I am referring to, let me ask a question. Have you ever leased a piece of equipment where at the end of the lease term you had the option to purchase the item for $1.00 or some other ridiculously small amount? If so, you should have treated that lease the same way you would have treated a normal purchase of equipment in your accounting records. In other words, the lease should have been capitaized. The equipment item should have been recorded in the Fixed Assets section of the Balance Sheet as a debit, and the down payment a credit to Cash, and the remaining balance owed set up as a Capital Lease or Lease Obligation in the liability section of the Balance Sheet. Interest and depreciation should be expensed as with any other purchase of an asset that has an installment loan associated with it. It is important to understand what constitutes a true lease from a dirty lease (a capital lease). The accounting requirements are very different. Read the article and let me know if you have any questions.

You might also like

- Introduction To Accounting - Lecture NotesDocument25 pagesIntroduction To Accounting - Lecture NotesMUNAWAR ALI96% (110)

- Case Study LeasingDocument3 pagesCase Study LeasingNicolaus Chandra100% (2)

- What is Financial Accounting and BookkeepingFrom EverandWhat is Financial Accounting and BookkeepingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- CSEC POB June 2015 P1Document9 pagesCSEC POB June 2015 P1Tia GreenNo ratings yet

- What Is A Balance SheetDocument11 pagesWhat Is A Balance SheetkimringineNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document50 pagesChapter 2najmulNo ratings yet

- Chasing Egregors - Paco Xander NathanDocument9 pagesChasing Egregors - Paco Xander Nathankimonth100% (1)

- Real AccountingDocument22 pagesReal Accountingakbar2jNo ratings yet

- Basic Accounting Concepts and PrinciplesDocument4 pagesBasic Accounting Concepts and Principlesalmyr_rimando100% (1)

- Title /course Code Principles of AccountingDocument6 pagesTitle /course Code Principles of AccountingM Noaman AkbarNo ratings yet

- Accounting - Basic Accounting: General LedgerDocument10 pagesAccounting - Basic Accounting: General LedgerEstelarisNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement Analysis For Cash Flow StatementDocument5 pagesFinancial Statement Analysis For Cash Flow StatementOld School Value100% (3)

- Accounting BasicsDocument13 pagesAccounting BasicsJerusa May CabinganNo ratings yet

- How To Read A Profit and Loss AccountDocument2 pagesHow To Read A Profit and Loss AccountAjay Kumar GuptaNo ratings yet

- Management Accounting Jargons/ Key TerminologiesDocument11 pagesManagement Accounting Jargons/ Key Terminologiesnimbus2050No ratings yet

- What Is 'Cash Flow'Document7 pagesWhat Is 'Cash Flow'Selvi VinoseKumarNo ratings yet

- Partnership Reading MaterialDocument4 pagesPartnership Reading MaterialLawish KumarNo ratings yet

- Lecture - Notes On PayrollDocument20 pagesLecture - Notes On Payrollkemmys100% (1)

- Equity Assets - LiabilitiesDocument6 pagesEquity Assets - LiabilitiesAcca IsdcNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Sole ProprietorshipDocument9 pagesAccounting For Sole ProprietorshipGerlie100% (1)

- DepreciationDocument3 pagesDepreciationahmedmushtaq041No ratings yet

- Account DefinationsDocument7 pagesAccount DefinationsManasa GuduruNo ratings yet

- ACNT1303lecture NotesDocument16 pagesACNT1303lecture NotesgrunebodNo ratings yet

- JKWCPA Accounting 101 For Small Businesses EGuideDocument13 pagesJKWCPA Accounting 101 For Small Businesses EGuideAlthaf CassimNo ratings yet

- Finance For Non-Financial ManagerDocument23 pagesFinance For Non-Financial ManagerMahrous100% (7)

- Tally NotesDocument203 pagesTally NotesSachin SharmaNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting: Sir Syed Adeel Ali BukhariDocument25 pagesFinancial Accounting: Sir Syed Adeel Ali Bukhariadeelali849714No ratings yet

- What Is A Partnership?: Two or More IndividualsDocument7 pagesWhat Is A Partnership?: Two or More IndividualsGudo MichaelNo ratings yet

- Accounting Equation PDFDocument9 pagesAccounting Equation PDFUba abednego100% (1)

- Accounting TerminologyDocument26 pagesAccounting TerminologyCynard Gonzales EspiloyNo ratings yet

- Groups: Non Revenue Primary Groups Capital AccountDocument7 pagesGroups: Non Revenue Primary Groups Capital AccountPallavi Shivanna GowderNo ratings yet

- Basics Accounting ConceptsDocument25 pagesBasics Accounting ConceptsMamun Enamul HasanNo ratings yet

- Accounting Basics - Assets, Liabilities, Equity, Revenue, and ExpensesDocument4 pagesAccounting Basics - Assets, Liabilities, Equity, Revenue, and ExpensesShah JehanNo ratings yet

- Understanding AccountingDocument20 pagesUnderstanding Accountingrainman54321No ratings yet

- Chapter 4 AccountingDocument22 pagesChapter 4 AccountingChan Man SeongNo ratings yet

- Tally 9Document18 pagesTally 9Romendro ThokchomNo ratings yet

- Managerial Finance, Financial Accounting and Analysis For Engineering Managers PDFDocument5 pagesManagerial Finance, Financial Accounting and Analysis For Engineering Managers PDFAshuriko KazuNo ratings yet

- 1st year-BSA-Willmer Muñoz (Week1-15)Document10 pages1st year-BSA-Willmer Muñoz (Week1-15)Myxxie ArtsNo ratings yet

- ThinkaboutthisDocument9 pagesThinkaboutthisBenicel Lane M. D. V.No ratings yet

- Basic Bookkeeping Principles For Your Small BusinessDocument5 pagesBasic Bookkeeping Principles For Your Small BusinessMariam Akuetiemhe ArunNo ratings yet

- Short Essay 3: UnrestrictedDocument3 pagesShort Essay 3: UnrestrictedSatesh KalimuthuNo ratings yet

- What Is A Chart of AccountsDocument2 pagesWhat Is A Chart of AccountsJonhmark AniñonNo ratings yet

- Basic Accounting TermsDocument3 pagesBasic Accounting TermsAllyza VillapandoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document28 pagesChapter 3Kibrom EmbzaNo ratings yet

- Accounting PrinciplesDocument13 pagesAccounting PrinciplesDGTM online platformNo ratings yet

- Analyze Cash Flow The Easy WayDocument2 pagesAnalyze Cash Flow The Easy Wayanilnair88No ratings yet

- Acount BitDocument1 pageAcount BitOrbin SunnyNo ratings yet

- Accenture - 1 B Com ProfileDocument7 pagesAccenture - 1 B Com ProfileTHIMMAIAH B CNo ratings yet

- Bookkeeping Module 1Document11 pagesBookkeeping Module 1Cindy TorresNo ratings yet

- Preparation TB and BSDocument21 pagesPreparation TB and BSMarites Domingo - Paquibulan100% (1)

- The Key Elements of The Financial PlanDocument27 pagesThe Key Elements of The Financial PlanEnp Gus AgostoNo ratings yet

- Local Media3038223883012324361Document77 pagesLocal Media3038223883012324361Bria Charmaine CutinNo ratings yet

- Financial AnalysisDocument22 pagesFinancial Analysisnomaan khanNo ratings yet

- EBITDA Ee-Bit-Dah Is The Before, ,, And: Initialism GaapDocument3 pagesEBITDA Ee-Bit-Dah Is The Before, ,, And: Initialism GaapPankaj_Chaudha_7767No ratings yet

- Financial AccountingDocument5 pagesFinancial AccountingRiza CabellezaNo ratings yet

- Beginners' Guide To Financial StatementsDocument7 pagesBeginners' Guide To Financial StatementsIbrahim El-nagarNo ratings yet

- Accounting Fundamentals II: Lesson 7 (Printer-Friendly Version)Document6 pagesAccounting Fundamentals II: Lesson 7 (Printer-Friendly Version)gretatamaraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document2 pagesChapter 8Bellla AgustinaNo ratings yet

- How To Prepare Balance SheetDocument29 pagesHow To Prepare Balance SheetRamiro Magbanua FelicianoNo ratings yet

- What Is A Chart of Accounts?: Financial Statements Balance Sheet Accounts Income Statement AccountsDocument12 pagesWhat Is A Chart of Accounts?: Financial Statements Balance Sheet Accounts Income Statement AccountsRoanNo ratings yet

- Basic Acc QuesDocument10 pagesBasic Acc QuesAli IqbalNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals 02 Accounting Interview QuestionsDocument37 pagesFundamentals 02 Accounting Interview Questionsnatalia.velianoskiNo ratings yet

- Cameral AccountingDocument4 pagesCameral Accountingchin_lord8943No ratings yet

- New TIP Course 6 DepEd TeacherDocument100 pagesNew TIP Course 6 DepEd TeacherHelen HidlaoNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 3RDDocument29 pagesMapeh 3RDmarkNo ratings yet

- SPM P3 Speaking Test (F5 Unit 6)Document3 pagesSPM P3 Speaking Test (F5 Unit 6)deathangel88 Gt100% (2)

- Importance of French Revolution On Romantic LiteratureDocument4 pagesImportance of French Revolution On Romantic Literaturegohilharsh0451No ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Log Ucsp RevisedDocument46 pagesDaily Lesson Log Ucsp RevisedHin Yan100% (1)

- F6MYS 2014 Jun QDocument12 pagesF6MYS 2014 Jun QBeeJuNo ratings yet

- GPS 4500 v2: Satellite Time Signal ReceiverDocument4 pagesGPS 4500 v2: Satellite Time Signal ReceiverCesar Estrada Estrada MataNo ratings yet

- Artikel Syekh Ibrahim Musa Sang Inspirator Kebangkitan Oleh Kel.12Document10 pagesArtikel Syekh Ibrahim Musa Sang Inspirator Kebangkitan Oleh Kel.12baskaraNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis On Bumrungrad' Global SDocument8 pagesCase Analysis On Bumrungrad' Global SSahil AnujNo ratings yet

- (AAR Teaching Religious Studies) Linda L. Barnes - Inés M. Talamantez - Teaching Religion and Healing (2006, Oxford University Press, Incorporated) - Libgen - LiDocument468 pages(AAR Teaching Religious Studies) Linda L. Barnes - Inés M. Talamantez - Teaching Religion and Healing (2006, Oxford University Press, Incorporated) - Libgen - Lihakaldama13No ratings yet

- Accounting EquationDocument14 pagesAccounting EquationDindin Oromedlav LoricaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Enron 2Document17 pagesJurnal Enron 2Mochamad RisnandaNo ratings yet

- Kerala PSC Exams Timetable - January 2012Document9 pagesKerala PSC Exams Timetable - January 2012www.examkerala.comNo ratings yet

- Gem 2015 Special Report On Social Entrepreneurship 1464768244Document44 pagesGem 2015 Special Report On Social Entrepreneurship 1464768244Irfan AzmiNo ratings yet

- Chapter Six - Supply Chain DesignDocument3 pagesChapter Six - Supply Chain DesignPattraniteNo ratings yet

- Integrated Coastal Resources Management Project (ICRMP) : Sustaining Our Coasts: The Ridge-to-Reef ApproachDocument47 pagesIntegrated Coastal Resources Management Project (ICRMP) : Sustaining Our Coasts: The Ridge-to-Reef ApproachCHOSEN TABANASNo ratings yet

- Performance Management Session 7 and 8Document36 pagesPerformance Management Session 7 and 8rohitgoyal207No ratings yet

- THEO530 Book Critique 1 Heikkinen "Two Views On Women in MinistryDocument10 pagesTHEO530 Book Critique 1 Heikkinen "Two Views On Women in MinistryCrystal HeikkinenNo ratings yet

- Omgeo ALERT® 56 Product Release InformationDocument16 pagesOmgeo ALERT® 56 Product Release InformationFritz BirchmayerNo ratings yet

- Markopedia: 2. STP & 7PsDocument5 pagesMarkopedia: 2. STP & 7PsAnshu BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Anga and Adhiratha Royal DescentDocument11 pagesAnga and Adhiratha Royal DescentDeepak Kumar JhaNo ratings yet

- ResumeDocument4 pagesResumeJulie RaftiNo ratings yet

- Legal Education in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesLegal Education in The PhilippinesSteve B. SalongaNo ratings yet

- DIG - Vir Jen Shipping and Marine Services Vs NLRC 1983 Case DigestDocument4 pagesDIG - Vir Jen Shipping and Marine Services Vs NLRC 1983 Case DigestKris OrenseNo ratings yet

- Primanila Plans, Inc. v. Securities and Exchange CommissionDocument1 pagePrimanila Plans, Inc. v. Securities and Exchange CommissionCheCheNo ratings yet

- Witron Electromechanical TechnicianDocument2 pagesWitron Electromechanical Technicianbillel.morakechiNo ratings yet