Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mummy Research Without 'Informed Consent'? Ethics and Ancient

Mummy Research Without 'Informed Consent'? Ethics and Ancient

Uploaded by

Lilla HarmatiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mummy Research Without 'Informed Consent'? Ethics and Ancient

Mummy Research Without 'Informed Consent'? Ethics and Ancient

Uploaded by

Lilla HarmatiCopyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 14, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Without 'informed consent'? Ethics and ancient mummy research

I M Kaufmann and F J Rhli J Med Ethics published online July 29, 2010

doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.036608

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://jme.bmj.com/content/early/2010/07/29/jme.2010.036608.full.html

These include:

References P<P Email alerting service

This article cites 21 articles, 2 of which can be accessed free at:

http://jme.bmj.com/content/early/2010/07/29/jme.2010.036608.full.html#ref-list-1

Published online July 29, 2010 in advance of the print journal. Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

Advance online articles have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet appeared in the paper journal (edited, typeset versions may be posted when available prior to final publication). Advance online articles are citable and establish publication priority; they are indexed by PubMed from initial publication. Citations to Advance online articles must include the digital object identifier (DOIs) and date of initial publication.

To order reprints of this article go to:

http://jme.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to Journal of Medical Ethics go to:

http://jme.bmj.com/subscriptions

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 14, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

JME Online First, published on July 29, 2010 as 10.1136/jme.2010.036608 Research ethics

Without informed consent? Ethics and ancient mummy research

I M Kaufmann,1 F J Ruhli2,3

1 University Research Priority Program, University of Zurich, Switzerland 2 Institute for the History of Medicine, University of Zurich, Switzerland 3 Institute of Anatomy, University of Zurich, Switzerland

Correspondence to Dr F J Ruhli, Institute of Anatomy, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstr. 190, 8057 Zurich, Switzerland; frank.ruhli@anatom.uzh.ch Received 13 March 2010 Accepted 17 May 2010

ABSTRACT Ethical issues are of foremost importance in modern bio-medical science. Ethical guidelines and socio-cultural public awareness exist for modern samples, whereas for ancient mummy studies both are de facto lacking. This is particularly striking considering the fact that examinations are done without informed consent or that the investigations are invasive due to technological aspects and that it affects personality traits. The aim of this study is to show the pro and contra arguments of ancient mummy research from an ethical point of view with a particular focus on the various stakeholders involved in this research. Relevant stakeholders in addition to the examined individual are, for example, a particular researcher, and the science community in general, likely descendents of the mummy or any future generation. Our broad discussion of the moral dilemma of mummy research should help to extract relevant decision-making criteria for any such study in future. We specically do not make any recommendations about how to rate these decision-factors, since this is highly dependent on temporal and cultural afliations of the involved researcher. The sustainability of modern mummy research is dependent on ethical orientation, which can only be given and eventually settled in an interdisciplinary approach such as the one we attempt to present here.

INTRODUCTION

Ethical issues are of foremost importance in modern bio-medical science. For clinical studies, as well as the complex issues of how to deal with modern corpsesdsuch as body donation programmes or public anatomy exhibitionsdethical guidelines or at least lively socio-cultural public debates exist. There is also an increasing number of palaeopathological studies, research dealing with the bio-medical assessment of historic human remains1 and its impact on modern bio-medical science, is well respected.2e4 Such ancient human (and animal) remains do not only consist of skeletal ndings, but also of mummies with preserved soft-tissue. These can be found on every single continent.5 The most famous are ancient Egyptian mummies, but also the European Neolithic Iceman (tzi) has become a prominent object of scientic investigation. Despite the great interest in these mummies, very few discussions about how to generally treat these ancient bodies can be found in public debates. One such public debate arose in 1980 when the Egyptian president Anwar el-Sadat ordered the closure of the Royal Mummy exhibition room in

Kaufmann IM, RuhliArticle author (or their employer) 2010. Copyright FJ. J Med Ethics (2010). doi:10.1136/jme.2010.036608

the Egyptian Museum in Cairo due to religiousethical reasons. Besides limited public debates, very few scientic reports hitherto address ethically disputable issues of ancient mummy or bone research.6e9 Holm10 uses the issue of ancient DNA sampling to address a few thoughts on a possible lack of privacy and how to address this issue based on current ethical criteria, such as consent of the dead persons descendants or culturally-linked communities. He concludes that common modern ethical assessments fail for such ancient cases. Thus, both the public and the scientic debate fall short in addressing possible concerns or in initiating a sound ethical reection. This apparent lack of rigorous ethical discussion and scientic argumentation about ancient mummy research is particularly striking due to various factors. First, any modern examination on historic corpses is done a priori without informed consent of the deceased. Second, the research undertaken on such a body is often invasive either in terms of technological aspects or in terms of personality traits. The recent enormous methodological evolutiondboth in the social sciences and particularly in the natural sciencesdallows researchers to gain more intimate information about historic personalities, often by means of invasive (tissue-destroying) methods. Third, public and scientic reports about such ndings do not follow the common criteria of medical privacy, by explicitly and specically naming major diseases or causes of death of a famous ancient individual, such as a former king or pharaoh. Thus, we attempt hereby to advance the ethical debate in ancient mummy research. The aim of our study is to conduct a stakeholder analysis showing the pro and contra arguments of ancient mummy research for the various involved interest groups (eg, the mummy itself, descendents and researchers) and with respect to various cultural concepts. The study will be theoretically based on the literature about stakeholder theory and linked to the normative theory of ethics. The stakeholder approach is a valuable instrument, not only to identify interest groups, but also to balance and judge those interests according to moral relevance, legitimacy or economic purpose.11 It has widespread acceptance, especially in management sciences11 12 and in ethical reasoning used in moral dilemma situations.13 14 We started by clustering relevant stakeholders into four categories and specifying their variable interests and arguments pro and contra relative to ancient mummy research. We continued the evaluation of these arguments with respect to moral content and identied what we call the moral

1 of Produced by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd under licence. 6

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 14, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research ethics

dilemma. We will further introduce an ethical concept that facilitates us in reecting about ethical pitfalls produced by the dilemma situation in light of the ethical theory. However, it is specically not the goal of this paper to present ultimate recommendations about how to ethically make decisions, but we want to start a discussion about how ethics can be integrated into the research agenda of ancient mummy investigations. To facilitate the outline, only issues about the scientic examination of mummies will be addressed. We do not discuss whether and how to publicly exhibit them, whether and how to restore/conserve them or how to appropriately communicate research results. In fact, we focus on moral issues that can arise in connection with conicts of interests, technological advancements or new possibilities of action. We further exclude non-moral questions such as purely economical, political or legal issues. possible pro and contra arguments. We identied the following four categories that are lled with arguments in favour of or against mummy research (see also gure 1 and table 1): 1. Religion and culture, 2. Law and guidelines, 3. Information and progress of knowledge, 4. Individualism and the right of integrity.

Religion and culture

Religious arguments are possibly positive and negative. With regard to ancient Egyptian cultural beliefs, it was of foremost importance to be remembered after death, not to die for a second time.18 Research could function as one possibility to retain the individual in memory and to inform the public about the socio-cultural roots. On the other hand, the peace of the deceased is a great and protectable good not only in ancient cultures, but also today.

MATERIAL, METHODS AND DEFINITIONS

In this study, mummy is dened as human remains with various degrees of soft-tissue preservation. We will not consider specic short-term legalistic denitions of when a body has to be dealt with forensically as a mummy and when the legal rights of individuality expire. By identifying stakes and stakeholders of ancient mummy research, we implicitly refer to the concept of the stakeholder theory without taking the theoretical heterogeneity into account. A good overview of the stakeholder theory is provided by various authors.11 12 15 16 Stakeholders are dened subsequently in the broadest sense, by means of any interest group affected by ancient mummy research. In this view, all relevant stakeholders are groups or individuals that might be affected by individual rights such as liberty, integrity or dignity, but also include economic or political interests. A stake in the broadest meaning is therefore an interest that is politically, economically or morally driven. To contribute to the discussion of morally relevant stakeholders, we refer to the normative understanding of morality. Normative is understood as a judgemental comment on norms and principles of conduct or intentions of conduct instead of a descriptive narrative of values or norms that are factually lived by a society, interest group or an individual. The normative moral point of view attempts to ask what norms or values should factually guide an individual, group or society. The way we use the term ethics or ethical reection, therefore, relates to a judgemental comment on norms and values from a normative point of view.17 By taking into account different normative positions, ethical reection can contribute to the catalysation of decision processes and give orientation within ancient mummy research. For instance, what is good or what is bad about ancient mummy research? Who shall decide, based upon what type of criteria, how to conduct invasive procedures? Also, ethics takes into account different perspectives and provides practical advice. It does not allow anyone to escape from responsibility nor does it make any claims for ultimate justication.

Law and guidelines

The international code of conduct of the International Council of Museums19 actually strongly encourages research on museum specimens. Thus, from a legal point of view, research on mummies, which is of benet for the advancement of science, should be performed. Since there are no clear guidelines about how to specically perform research on ancient mummied samples, there is no legal basis on how to best perform such studies, similar to the good clinical practicedguidelines (as issued by the US Food and Drug Administration or the European Commission). In the future, mummy research guidelines shall address issues such as personal rights of the dead (medical data), who shall possess such data and how one may present it within and outside of the research community. Also, the diagnostic validity and invasiveness of the major methods used shall be addressed.

Information and progress of knowledge

Such arguments are mostly positive towards ancient mummy research. Access to ancient mummies for the purpose of research is one of the most important interests of the single mummy researcher, in terms of research progress, professional reputation, nancial benets and funding. For the research community, mummy remains are of great scientic importance as there are no substitutes for such samples. Bio-medical research using mummied tissue and bone have made signicant contributions to the progress in science20 21 and the value of such studies has been highlighted on multiple occasions.2e4 The research results also provide information to the broader public to understand ancient life and the culture of the mummys homeland. This in turn strengthens an interdisciplinary exchange, which is important for the advancement of knowledge in general.

Individualism and the right of integrity

Individualism is a basic ethical premise and a fundamental proposition about value. It denes human beings as an end in themselves, and not just as a means to broader social ends. The right of integrity is understood as the elemental right of each human being to be protected from any kind of harm.22 Research on mummies has to consider the aspects of individualism and the right of integrity. This is due to the fact that investigation methods are sometimes invasive and destroy tissue or the investigations are conducted without the informed consent of the deceased. On the other hand, individualism may be supported when research results put aside false accusations (eg, speculations about cause of death or disease).

Kaufmann IM, Ruhli FJ. J Med Ethics (2010). doi:10.1136/jme.2010.036608

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Categories of interest: pro or contra mummy research

Summarising the claims of several stakeholdersi affected by mummy research, shows that there is a relatively wide range of

i The categories are drawn from a list of stakeholders, see table 1. The identication of all stakeholders as well as their interest is based on our own knowledge. Without discussing the groups and interests in detail, we directly cluster them in four main categories.

2 of 6

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 14, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research ethics

Research is always confronted with a plurality of interests. The motivation behind those interests is as manifold as the interests itself, ranging from economic benets, legitimacy claims or moral concerns. Our objective is to contribute to the ethical discussion about ancient mummy research. We will now continue with the analysis of these arguments with moral content. biological wholeness, (2) experiential wholeness, (3) intact wholeness and (4) inviolable wholeness.24 Biological wholeness refers to the unity of the body in terms of anatomical aspects and to the proper operation of the body or parts of the body in terms of functional aspects. The question of ethical interest is therefore to what extent modications of the body are offences against biological wholeness. Experiential wholeness relates to the matter of a subjective experience of bodily wholeness. Subjective-experiential wholeness is not necessarily similar to a functionally perfect body. Even when the body functions less than satisfactory, a human may still feel a kind of bodily wholeness. With regard to a corpse this is of less importance. However, it becomes meaningful for ancient mummies, if we take subjective feelings of bodily wholeness into account before the mummies death. Intact wholeness strongly mirrors a religious aspect of bodily wholeness. This means that the body is intrinsically important for personal identity. Sometimes intact wholeness is characterised in terms of sacredness and sanctity, stressing the meaning of intactness and completeness.24 Specically, an intact physical body was a conditio sine qua non in Ancient Egyptian beliefs to gain immortality. Thus, this was the religious reason for the enormous tradition of articial mummication attempts in this particular culture. Inviolable wholeness involves the possible misdoing of violating the integrity of the human body. As discussed earlier, this view includes body-oriented and person-oriented integrity. At this point, it is meaningful to refer back to Kants philosophy.23 According to Kant,23 we have not only duties concerning ourselves and other persons, but also regarding other beings such as animals and dead bodies. To realise this duty towards others is to realise the moral duty we have to ourselves, in order to respect the humanity of personhood. With regard to ancient mummy research, Kants comment on deceased persons23 is of special interest, as it is in favour of a right of integrity for mummies.

Personal integrity versus personal advance: the moral dilemma and its ethical conceptualisation

In light of moral reasoning, the debate about ancient mummy research might run into two conicting positions. This is on the one hand, the right of integrity including the right of peace for the deceased. On the contrary, there is the importance of the progress of knowledge and the personal advancement of the researcher in contributing to such progress. Generally said the human body alive or dead has a moral value. This is rooted in religious thoughts as well as in philosophical thinking. Violation of such a moral value is a violation of a persons integrity. Bodily integrity is therefore an important issue in maintaining the integrity of a person and as such is important for the practice of research. The notion of bodily integrity incorporates different aspects. One distinction made, is between body-oriented integrity and person-oriented integrity. Following Kants philosophy23 a body-oriented integrity view is focused on the duties towards our own body rather than to those of others. For ancient mummy research the personoriented view of integrity is more important. Person-oriented integrity includes the right to be safeguarded against violations of others and the right to self-control over the body. This is especially important within medical ethics as treatments without explicit consent can already be considered as a violation. According to the principles of biomedical ethics developed by Beauchamp and Childress,13 bodily integrity as person-oriented integrity can be further interpreted with regards to: (1)

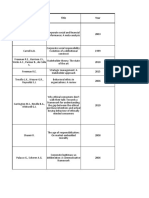

Table 1

Exemplary list of pro and cons of mummy research interests by main stakeholders

Possible pro eReligious (eg, to dismiss false acquisitions of a certain medical diagnosis) eReligious support for (eg, not to be forgotten) eElimination of wrong accusations (eg, media speculation of possible causes of death) eProvide information about a set of religious and moral paradigms eSupport the benet for all mankind through scientic mummy research eIn some cases informed consent of individual is available (eg, modern mummies of famous politicians or clerics) eResearch may physically protect a mummy from grave robbers (mummy no longer stored in a tomb) ePersonal interests (nancial benets, professional reputation, pure curiosity, progress of ones own research) eNo sample substitutes are available (uniqueness of the mummy as a research object) eProgress of research in general (eg, development of new research methods) eMummies as a means to establish a new eld of research eProvides information on mummies and ancient cultures to the public eIncreased media interest thanks to research eIncreased interest in the mummys country of origin, eg, foreign research teams eGains in scientic and cultural information, eg, for the progress of science eImpact of mummy research on other elds of research (side-effects) eTo satisfy ones own curiosity eKnowledge about ones own predecessor eIdentication of economical and/or political interests eMorale interests link with ones own cultural roots Possible contra eGeneral religious and cultural objections (eg, the right of peace for the deceased) eLack of patient privacy (complete medical data publicly available, may affect ones own authority) eResearch done without informed consent eIn some cases an invasive procedure is used (x-ray, histology) eIn some cases the mummy is removed from the tomb (lack of peace for the dead) eInstrumentalisation/lack of autonomy (of ones own body)

Stakeholder Articial mummy/ Ancient culture

Single researcher/ research community

eAbsence of any benecial research results or personal interests despite research efforts eBad reputation, eg, by using incorrect methodologies, accusations of unethical behaviour towards a researcher

Tourism/museums

eDestruction of mummies as a result of research methodologies eLimited access to touristic areas due to scientic activity

Civil society

eResearch may contradict ones own moral paradigm for example inappropriate risk-benet ratio eReligious reasons eNegative research results may act as prejudgements or prejudice against present-day descendents (eg, racism)

Descendents (present, not ancient ones)

Kaufmann IM, Ruhli FJ. J Med Ethics (2010). doi:10.1136/jme.2010.036608

3 of 6

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 14, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research ethics

Figure 1 Story of argumentation.

Objective/ Goal Ask for ethical concerns within ancient mummy research A value free identification and presentation of such possible concerns

Step 1

Stakeholder analysis: Identification of possible stakeholders affected by ancient mummy research

Result 1: List of relevant stakeholders and their interests (economic, legal, moral)

Step 2

Discussion of the morally relevant interests; identification of the moral dilemma

Result 2: Integrity vs. progress of knowledge as the moral dilemma

Step 3

Discussion of the moral dilemma exemplified by four pitfalls and based on ethical principles

Result 3: Recommendations

Conclusion

Balancing the arguments

Outlook: Developing an ethical framework

In the light of these remarks, disregarding a persons right of integrity incorporates harming this person or violating their right of autonomy. With regard to ancient mummies, the problem of violation is different compared to those of a living person. Is it possible to harm the dead? Is the bodily integrity of the mummy to some extent at stake through modern research efforts? As there are no explicit discussions about mummies, we analysed earlier similar discussions. For example, the right of bodily integrity has been discussed for tissue derivation and organ transplantation from corpses. Within these discussions, offending the right of integrity is as much about the possibility of harming the dead, as about the autonomy and interests of the dead.25 Partridge26 holds the view that posthumous harm is impossible because no one can retain interests after death. Levenbook27 is more in favour of the possibility of posthumous harm. Also Levenbook27 stresses the metaphysical and metaethical difculties in defending a fully developed concept of posthumous harm. She argues that it is worthwhile starting a discussion on this topic. In assuming an intrinsic moral value for humans dead or alive, our argumentation is in line with a moderate perspective on integrity issues for mummy research. We assume that it is also desirable to discuss the problem of posthumous harm to mummies. This is especially true with regards to articially prepared corpses, where we know that the person had a specic desire for the time after his death, which was rooted in his cultural and religious traditions. We therefore continued with the examination of possible challenges that are at stake and might bring into question the integrity issue for mummy research. We identied four such possible pitfalls and discussed them in light of bodily integrity and wholeness.

inviolable wholeness. This could be especially true with regards to ancient Egyptian mummies, as the discussion of very personal information could offend their wish of being remembered as strong and healthy. The risk of commercialisation and thus alteration of initial scientic purposes of such individual data opens up another, hereby not treated, area of ethical conicts. However, imaging data or macroscopic pictures may reveal information at a different level than written sources only and thus should be treated differently when considering the personal rights of the deceased. Some issues dealt with in a clinical settingdsuch as publishing only anonymised resultsdis hard to achieve if one deals specically with the examination of wellknown historical individuals (eg, royal Egyptian mummies). Yet, it is achievable in cases where the data of less known mummiesdwith known individual namesdare published. However, this contradicts the imminent scientic desire (and often specically requested by journals and grant bodies) to provide as much reproducible individual data as possible.

The use of non-invasive and invasive examination methods

Current research on mummies is dependent on the use of modern technologies. Such technologies diverge in their degree of invasiveness. Often completely non-invasive examinations suggestively reveal a lesser degree of scientic proof and thus are less respected within the scientic community. Often, such invasive procedures are only regarded as conrmation of an earlier non-invasive nding. A recent exemplary example was the conrmation by invasive histological examinations28 what had already been shown by non-invasive computed tomography as the cause of death of the Iceman.29 The more invasive a technology is the more it harms the concept of wholeness. The exemplary newly arising methods such as DNA analysis will likely revolutionise the whole eld of mummy research. The impact of such new methods in terms of ethical issues is huge. DNA analysis may allow the detection of individual markers of disease, as well as allow tracing of family relationships, such as inbreeding in royal families or reveal unexpected ethnic relationships. The denition of a mummys descendants as adequate proxy decision makers is full of pitfalls, too. As Holm10 highlights, a culturally well informed scientist may have more

Kaufmann IM, Ruhli FJ. J Med Ethics (2010). doi:10.1136/jme.2010.036608

How to publish individual biomedical data

The public access to individual biomedical data is a well-established topic in ethical discussions. If such data was made available, one could claim open access at least for all scientists, if not for the general public. The use and production of biomedical data can therefore contradict the concepts of intact and

4 of 6

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 14, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research ethics

ethical insights into the cultural beliefs of an ancient mummy than descendants who do not share a common cultural belief, but only ethnical proximity. In some cases, such as for the Neolithic Iceman, based on modern DNA analysis30 it could be proven that genetic proxies no longer exist today. Thus, fake claims of descendancy could be repudiated by genetic analyses. Destroying parts of the mummy by for example unwrapping the corpse, offends the biological wholeness because the unity of the body is destroyed. For the same reason, it is against inviolable wholeness. Experiential wholeness might be disturbed with regard to the desire of the mummy to have the subjective feeling of bodily wholeness before death. Keeping in mind that Egyptians made great efforts to be prepared for life after death, might offend aspects of intact wholeness as well. The main issues are about: (1) to what degree the process of embalming done for the physical preservation of the body, the necessary mutilations required for this process (eg, removal of internal organs) and thus the desired integrity of the body, may have been regarded as a religious rather than a mechanical concept; (2) not only the integrity of the deceased, but also the invasiveness of a method may be a problem when examining such a unique material; (3) to what extent will current investigation methods impact the use of this unique material when future generations of scientists want to examine or re-examine it. To sacrice ones own bodily integrity for the progress of society and other individuals is not only present in modern-times in organ or body donations, but may be assumed to be the case for at least some deceased ancient individuals, too, however this can no longer be proven. Nevertheless, we would like to point out that not all invasive procedures during the examination of mummies are de facto negative for the corpse; conservation attempts are one such positive by-product. Often, it is better to store a body or body parts in well-climatised scientic laboratories than in their original burial grounds; thus again an invasive procedure may be of benet to the mummy. current ethical concepts, which is highly dependent on zeitgeist (the spirit of the age or time) and on the cultural background of the ethical framework being applied. Thus, we do not intentionally recommend a specic solution or decision, but rather we want to stimulate an open-minded discussion. Without knowing or exactly understanding the ethical concept of the deceased, it is dangerous and short-sighted to assume based on current knowledge only how to best act in such unique scientic situations. However, any ethical decision pro or contra to mummy research should try to respect the interests of the various stakeholders. For genuine progress in modern medical research, invasive analyses of historic mummied tissuedafter careful ethical considerationsdmay be well supported from our personal perspective. The intellectual process of ethical decisionmaking itselfdindependent of its nal judgementdis actually already a progress in the study of ancient human remains.

CONCLUSION

The specic debate on whether at all and if so how to examine (and display) ancient mummies is one of great controversy. One has to be fully aware, that the issue of how to store and to analyse ancient mummies and how to communicate the respective research results in an ethically appropriate way is highly dependent on current local ethical frameworks and culture. Thus, a nal recommendation is beyond the scope of this study. Finally, any attempt to assess the best interests for long-term deceased individuals will always be incomplete. At least in some cases, these individuals could not fathom the concept of the modern technological investigation possibilities, but were also not aware about the whole concept of modern science in general and its needs and ethical bases.

Competing interests None. Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES Type of mummy

In ethical judgement, one should also differentiate between whether a child or adult mummy is involved. This is especially true in cases of articial mummication, where an adult individual intentionally underwent preservation and thus indirectly took into consideration the possibility of his physical availability to later generations. In the case of accidental mummication, such as for ice mummies, this may be regarded differently. For such mummiesdincluding articially embalmed minorsdone may assume that the deceased was not aware of the possibility of preservation and of the scientic availability of his body remains to future generations. In both cases, articial and natural mummication, consent for later examinations of their mummy is missing. With regard to articial mummication, as in the case of Egyptian mummies, cultural and religious knowledge can be taken into account relative to questions of consent. Nevertheless, the idea of wholeness might be harmed when one considers the reasons we discussed earlier. Finally, for some researchers the degree of intactness of the ancient body decides the extent of invasive procedures, thus if tissue destroying examinations will be performed at all.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. Ortner D, Putschar W. Identication of Pathological Conditions in Human Skeletal Remains. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985:28. Bosch X. Look to the bones for clues to human disease. Lancet 2000;355:1248. Metcalfe N. A description of the methods used to obtain information on ancient disease and medicine and of how the evidence has survived. PMJ 2007;83:655e8. Kilbourne ED. Inuenza immunity: new insights from old studies. J Infect Dis 2006;193:7e8. Aufderheide AC. Progress in soft tissue paleopathology. JAMA 2000;284:2571e3. Smith E. Tutankhamen. London: Routledge, 1923. Bahn PG. Do not disturb? Archaeology and the rights of the dead. J Appl Philos 1984;1:213e25. Nathan B. Egyptian mummies. Lancet 1997;350:450. David AR. Authors reply. Lancet 1997;350:450. Holm S. The privacy of Tutankhameneutilising the genetic information in stored tissue samples. Theoretical Medicine & Bioethics 2001;22:437e49. Mitchell R, Agle B, Wood D. Toward a theory of stakeholder identication and salience: dening the principle of who and what really counts. Acad Manag Rev 1997;22:853e86. Donaldson T, Preston L. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad Manag Rev 1995;20:65e91. Beauchamp T, Childress J. Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. Mepham BA. Framework for the ethical analysis of novel foods: the ethical matrix. J Agricult Environ Ethics 2000;12:167e76. Jones T. Instrumental stakeholder theory: a synthesis of ethics and economics. Acad Manag Rev 1995;20:404e37. Trevino L, Weaver G. The stakeholder research tradition: converging theorists - not convergent theory. Acad Manag Rev 1999;24:222e7. Huppenbauer M, De Bernadi J. Kompetenz ethik. Zurich Versus Verlag 2003. Feucht E. Das Grab des Nefersecheru (TT 296) Mainz: Ph. von Zabern 1985. ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums. In: Museums ICo, ed. Paris: ICOM; 2006. Zink AR, Sola C, Reischl U, et al. Characterization of mycobacterium tuberculosis complex DNAs from Egyptian mummies by spoligotyping. J Clin Microbiol 2003;41:359e67. Taubenberger JK, Reid AH, Lourens RM, et al. Characterization of the 1918 inuenza virus polymerase genes. Nature 2005;437:889e93.

Interests of the living versus those of the death

Based on the above analyses, most of the criteria on whether (and if so how) to analyse ancient mummies can be concluded based on the diverse interests of the living (researcher, general public) and the dead (mummied corpse). Balancing these interests is crucially dependent on various factors such as,

Kaufmann IM, Ruhli FJ. J Med Ethics (2010). doi:10.1136/jme.2010.036608

5 of 6

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 14, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research ethics

22. 23. 24. 25. Peers S, Ward A. The EU Charter of fundamental rights: politics, law and policy 2004. Kant I. The metaphysics of morals. In: Gregor MJ, Wood A, eds. Practical Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996:353e603. Dekkers W, Hoffer C, Wils J- P. Bodily Integrity and male and female circumcision. Medicine, Health and Philosophy 2005;8:179e91. Ashcroft RE, Dawson A, Drapper H, et al. Principles of Health Care Ethics. Wiley, 2007. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. Partridge E. Posthumous interests and posthumous respect. Ethics 1981;91:243e64. Levenbook BB. Harming someone after his death. Ethics 1984;94:407e19. Nerlich A, Peschel O, Egarter-Vigl E. New evidence for Otzis nal trauma. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1138e9. Pernter P, Egarter Vigl E, Gostner P, et al. Radiologic proof for the Icemans cause of death. J Archaeol Sci 2007;34:1784e6. Ermini L, Olivieri C, Rizzi E, et al. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the Tyrolean Iceman. Curr Biol 2008;18:1687e93.

6 of 6

Kaufmann IM, Ruhli FJ. J Med Ethics (2010). doi:10.1136/jme.2010.036608

You might also like

- Sociological Theory in The Classical EraDocument16 pagesSociological Theory in The Classical Eraglenn jospeh0% (1)

- STUDENT NOTES - Foundation and Principles of Bioethics in NursingDocument5 pagesSTUDENT NOTES - Foundation and Principles of Bioethics in NursingBlaiseNo ratings yet

- Krieger Nancy Epidemiology and The PeopleDocument394 pagesKrieger Nancy Epidemiology and The PeopleAnamaria Zaccolo100% (1)

- A Framework To Measure Corporate Sustainability Performance A Strong Sustainability-Based View of Firm PDFDocument18 pagesA Framework To Measure Corporate Sustainability Performance A Strong Sustainability-Based View of Firm PDFSonia Ramirez100% (1)

- Freeman PDFDocument27 pagesFreeman PDFJaqueline Fonseca100% (1)

- Anthropology 200 Review 1.29.14Document4 pagesAnthropology 200 Review 1.29.14Kirthana SrinivasanNo ratings yet

- Rose - 2012 - Democracy in The Contemporary Life Sciences-1Document14 pagesRose - 2012 - Democracy in The Contemporary Life Sciences-1Jaime Sebastián Cancino BarretoNo ratings yet

- Worst Human Experiments 1 To 5Document13 pagesWorst Human Experiments 1 To 5djumaliosmaniNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Science Ethics and Society118Document10 pagesRelationship Between Science Ethics and Society118Popoola FelixNo ratings yet

- Week 14Document9 pagesWeek 14Evander Sasarita MonteroNo ratings yet

- Name: Prado, Catherine A. Year and Section: BSN III-B Module 2 Activity Ethico-Legal Considerations in Nursing ResearchDocument2 pagesName: Prado, Catherine A. Year and Section: BSN III-B Module 2 Activity Ethico-Legal Considerations in Nursing ResearchCatherine PradoNo ratings yet

- Anthropology BiologicalDocument6 pagesAnthropology BiologicalBona MeladNo ratings yet

- Embryo Politics: Ethics and Policy in Atlantic DemocraciesFrom EverandEmbryo Politics: Ethics and Policy in Atlantic DemocraciesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Could Human Rights Supres BioethicsDocument22 pagesCould Human Rights Supres BioethicsDiego AndradeNo ratings yet

- 6.-Translational Stem Cell Research. Issues Beyond The DebateDocument462 pages6.-Translational Stem Cell Research. Issues Beyond The DebateCristian Joshua Hernandez GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Sidestepping The Embryo The Cultural Me PDFDocument22 pagesSidestepping The Embryo The Cultural Me PDFGabija PaškevičiūtėNo ratings yet

- The Ethical Dimension of Human Nature: A New Realist TheoryDocument12 pagesThe Ethical Dimension of Human Nature: A New Realist TheoryRechelle Anne Cabaron LaputNo ratings yet

- Ethical IsuesDocument12 pagesEthical IsuesAr Shahanaz JaleelNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Lessons 2Document13 pagesModule 1 Lessons 2Florelyn MabansagNo ratings yet

- TextOfBioethics PDFDocument228 pagesTextOfBioethics PDFNgoc HoangNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Culture, Sociology and Political Science Module 1Document26 pagesUnderstanding The Culture, Sociology and Political Science Module 1jmae9347No ratings yet

- Defining BioethicsDocument4 pagesDefining BioethicsMahdi BakkarNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics in The Perspective of Human Autonomy and DignityDocument13 pagesMedical Ethics in The Perspective of Human Autonomy and DignityTendayi Dumi KanengoniNo ratings yet

- BED 4107 Gerontology Lecture Notes MARCH 2020Document40 pagesBED 4107 Gerontology Lecture Notes MARCH 2020SHARON KIHORONo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Human Flourishing (PELEN) MARCH ACTIVITIESDocument3 pagesLesson 1 Human Flourishing (PELEN) MARCH ACTIVITIESMhelboy Gabejan AbalosNo ratings yet

- "Publish or Perish"-Who Publishes and Who Perishes?: Ethics in OrthodonticsDocument1 page"Publish or Perish"-Who Publishes and Who Perishes?: Ethics in OrthodonticsMaja Maja BułkaNo ratings yet

- PDF Social Science Research Ethics in Africa Nico Nortje Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Social Science Research Ethics in Africa Nico Nortje Ebook Full Chapterjulia.james301100% (1)

- Controversial Science: Controversial Experiments That Changed the World: The Ethical DilemmaFrom EverandControversial Science: Controversial Experiments That Changed the World: The Ethical DilemmaNo ratings yet

- Unruly Ethics On The Difficulties of A B PDFDocument23 pagesUnruly Ethics On The Difficulties of A B PDFAnelise Pigatto RigonNo ratings yet

- Science, Technology, and Society (STS) Hand-Out#6: Human FlourishingDocument5 pagesScience, Technology, and Society (STS) Hand-Out#6: Human FlourishingKclyn Remolona100% (1)

- Human FlourishingDocument6 pagesHuman FlourishingAira GaluraNo ratings yet

- Eurostem: An Ethical Framework For Stem Cell ResearchDocument9 pagesEurostem: An Ethical Framework For Stem Cell ResearchmynameistyanNo ratings yet

- MRR1 - Ged104Document2 pagesMRR1 - Ged104Mark Jason CarandangNo ratings yet

- Hot Topics For Argumentative EssaysDocument6 pagesHot Topics For Argumentative Essaysezmv3axt100% (2)

- Ethics and Research PhiDocument10 pagesEthics and Research PhiTuskegee RevisitedNo ratings yet

- Notes in STS PrelimDocument27 pagesNotes in STS Prelimbyunbakexo100% (1)

- Right To Know New Technologies and New CDocument16 pagesRight To Know New Technologies and New CLabtic UnipeNo ratings yet

- Environmental Ethics - SoebirkDocument5 pagesEnvironmental Ethics - SoebirkVarundeep SinghNo ratings yet

- The Tyranny of Utility: Behavioral Social Science and the Rise of PaternalismFrom EverandThe Tyranny of Utility: Behavioral Social Science and the Rise of PaternalismNo ratings yet

- Science (Fiction) and Posthuman EthicsDocument17 pagesScience (Fiction) and Posthuman EthicsBrandon García AlonsoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document23 pagesChapter 1Farhan AhmedNo ratings yet

- Environment Law 22Document26 pagesEnvironment Law 22shakti tripatNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual for Cultural Anthropology, 15th Edition, Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember download pdf full chapterDocument32 pagesSolution Manual for Cultural Anthropology, 15th Edition, Carol R. Ember, Melvin Ember download pdf full chaptertsawmfridau100% (11)

- Unit 2-Ethical ConsiderationsDocument54 pagesUnit 2-Ethical ConsiderationsThe Pupil PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument12 pagesChapter IAngelo F. Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Bioethics, Health, and InequalityDocument8 pagesBioethics, Health, and InequalityPier Paolo Dal MonteNo ratings yet

- STS Module 1.Document16 pagesSTS Module 1.Astra JoyNo ratings yet

- Bioeconomia Body & Society 2009 Hoeyer 1 24Document25 pagesBioeconomia Body & Society 2009 Hoeyer 1 24El PeTiNo ratings yet

- Tremain On The Government of DisabilityDocument21 pagesTremain On The Government of DisabilityFarshad JNo ratings yet

- Value Freedom Theory and MethodsDocument9 pagesValue Freedom Theory and MethodsHashimNo ratings yet

- Krieger Nancy Epidemiology and The People-1-297Document297 pagesKrieger Nancy Epidemiology and The People-1-297Luiza MenezesNo ratings yet

- 2 Ethical Aspects of Nursing ResearchDocument35 pages2 Ethical Aspects of Nursing ResearchGrape JuiceNo ratings yet

- The A Priori Method in The Social Sciences A Multidisciplinary Approach Jean Sylvestre Berge Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesThe A Priori Method in The Social Sciences A Multidisciplinary Approach Jean Sylvestre Berge Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFgene.pastor330100% (8)

- Course Code: 4663 Semester: Ste Autumn 2020Document8 pagesCourse Code: 4663 Semester: Ste Autumn 2020AKBAR HUSSAINNo ratings yet

- Why Study EthicsDocument6 pagesWhy Study Ethicsmimho1178No ratings yet

- Ge 7Document24 pagesGe 7Jenelyn SaalNo ratings yet

- Kurt Lewin Original - TraduzidoDocument38 pagesKurt Lewin Original - Traduzidomsmensonbg6161No ratings yet

- Towards A Critical Moral AnthropologyDocument4 pagesTowards A Critical Moral AnthropologyReza KhajeNo ratings yet

- Writing Assignment 9Document2 pagesWriting Assignment 9Omar MontesNo ratings yet

- Science WorksheetDocument2 pagesScience WorksheetMoc kiNo ratings yet

- Shallem Mining Company Challenge: StakeholderDocument4 pagesShallem Mining Company Challenge: Stakeholderkimberly oduroNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Business and Society 13th Edition Anne LawrenceDocument23 pagesTest Bank For Business and Society 13th Edition Anne Lawrencejezebelrosabella17pgNo ratings yet

- International CSR AssignmentDocument8 pagesInternational CSR AssignmentBenedictus Ardito AntadiputraNo ratings yet

- Project Two (Ayodele)Document48 pagesProject Two (Ayodele)Roseline OmoareNo ratings yet

- Introduction To GovernanceDocument11 pagesIntroduction To Governancefor thierNo ratings yet

- HGHGKJDocument66 pagesHGHGKJHuyenDaoNo ratings yet

- Theories in Accounting: ©2018 John Wiley & Sons Australia LTDDocument57 pagesTheories in Accounting: ©2018 John Wiley & Sons Australia LTDdickzcaNo ratings yet

- Value Maximization, Stakeholder Theory, and The Corporate Objective FunctionDocument2 pagesValue Maximization, Stakeholder Theory, and The Corporate Objective FunctionramdaneNo ratings yet

- Traxler 2020Document17 pagesTraxler 2020sita deliyana FirmialyNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Analysis: Trevor Sofield Professor of Tourism University of Tasmania Australia. Consultant: ITCDocument16 pagesStakeholder Analysis: Trevor Sofield Professor of Tourism University of Tasmania Australia. Consultant: ITCWade EtienneNo ratings yet

- Lesson 11 Business EthicsDocument17 pagesLesson 11 Business EthicsMylene SalvadorNo ratings yet

- Crane & Matten: Business EthicsDocument35 pagesCrane & Matten: Business EthicsR INDU SHEETALNo ratings yet

- Role of Stakeholders in Project Success - Theoretical Background and ApproachDocument12 pagesRole of Stakeholders in Project Success - Theoretical Background and ApproachOhiozua OhiNo ratings yet

- Aqua Danone Klaten Case and The Ethics TheoryDocument13 pagesAqua Danone Klaten Case and The Ethics TheoryAndina Diah HapsariNo ratings yet

- Original PDF Accounting and Financial Management Custom EditonDocument42 pagesOriginal PDF Accounting and Financial Management Custom Editonmarth.fuller529No ratings yet

- PLM MBA SOCRES WRITTEN REPORT v3 07122018Document8 pagesPLM MBA SOCRES WRITTEN REPORT v3 07122018Nemelyn LaguitanNo ratings yet

- Crane and Matten: Business Ethics (3rd Edition)Document34 pagesCrane and Matten: Business Ethics (3rd Edition)Peter ParkerNo ratings yet

- BUS SOC Chapter 1: The Corporation and Its StakeholdersDocument14 pagesBUS SOC Chapter 1: The Corporation and Its StakeholdersRaiyan JavedNo ratings yet

- The Corporation and Its Stakeholders: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument33 pagesThe Corporation and Its Stakeholders: Mcgraw-Hill/Irwinmajidshaikh3344No ratings yet

- Befekadu - Prposal - First DraftDocument63 pagesBefekadu - Prposal - First DraftFikreab Markos Dolebo100% (1)

- Marketing EthicsDocument25 pagesMarketing EthicsEngr Zubair Anwar Wada100% (1)

- Stakeholders TheoryDocument13 pagesStakeholders TheoryKazzandraEngallaPaduaNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument1,638 pagesResearchRajiv NaiduNo ratings yet

- Accounting Theory and Types of Theories in AccountingDocument10 pagesAccounting Theory and Types of Theories in AccountingKarinda BrilianaNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Theory - PresentationDocument12 pagesStakeholder Theory - PresentationMuhammad Khurram Shabbir100% (1)

- Juan F. Pujol, JR., Mba Bac 4Document61 pagesJuan F. Pujol, JR., Mba Bac 4Patrick AdiacNo ratings yet

- Corporate and Stakeholder Responsibility - Making Business Ethics A Two Way ConversationDocument25 pagesCorporate and Stakeholder Responsibility - Making Business Ethics A Two Way ConversationPALMIRA VILLARAN CHAVEZNo ratings yet

- Ethics MCQDocument5 pagesEthics MCQfsa100% (1)