Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Carina Granberg

Carina Granberg

Uploaded by

legarces23Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Levesque On Historical Literacy Winter 2010Document5 pagesLevesque On Historical Literacy Winter 2010legarces23No ratings yet

- Barton. Elementary Students' Ideas About Historical EvidenceDocument25 pagesBarton. Elementary Students' Ideas About Historical Evidencelegarces23No ratings yet

- School HistoryDocument7 pagesSchool Historylegarces23No ratings yet

- Micro Analysis and The Construction of The SocialDocument12 pagesMicro Analysis and The Construction of The Sociallegarces23No ratings yet

- 1.MIL 1. Introduction To MIL (Part 1) - Communication, Media, Information, Technology Literacy, and MILDocument35 pages1.MIL 1. Introduction To MIL (Part 1) - Communication, Media, Information, Technology Literacy, and MILMargerie Fruelda50% (2)

- DLP DIASS Q2 Week A - Settings, Processes and Tools in CommunicationDocument14 pagesDLP DIASS Q2 Week A - Settings, Processes and Tools in CommunicationKatrina BalimbinNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Educomp Smart ClassDocument4 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Educomp Smart ClassSantosh KmNo ratings yet

- Work SampleDocument32 pagesWork Sampleapi-356623029No ratings yet

- Sced 3311 Teaching Philosophy Final DraftDocument7 pagesSced 3311 Teaching Philosophy Final Draftapi-333042795No ratings yet

- Innovating Pedagogy 2022Document61 pagesInnovating Pedagogy 2022pacoperez2008No ratings yet

- Tle Carpentry DLLDocument36 pagesTle Carpentry DLLJessica Rebodos100% (1)

- Ubd Social StudiesDocument8 pagesUbd Social Studiesapi-253205044No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 3 Grade 5Document6 pagesLesson Plan 3 Grade 5api-496650728No ratings yet

- Ped 9 Content Module 9Document16 pagesPed 9 Content Module 9Arline Hinampas BSED-2204FNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Arithmetic SequencesDocument35 pagesMathematics Arithmetic SequencesElmer B. Gamba100% (1)

- Week5 Quarter-2-DLl DLPDocument5 pagesWeek5 Quarter-2-DLl DLPRHODORA GAJOLEN100% (2)

- Art Science Integration Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesArt Science Integration Lesson Planapi-237170589No ratings yet

- Review Writing Lesson Plan PDFDocument3 pagesReview Writing Lesson Plan PDFapi-662176377No ratings yet

- PLC ProjectDocument9 pagesPLC Projectapi-531717294No ratings yet

- LP Cot1 2021 2022 PeDocument4 pagesLP Cot1 2021 2022 PeHannah Katreena Joyce JuezanNo ratings yet

- M1 - L2 - 1 - The CentepedeDocument1 pageM1 - L2 - 1 - The CentepedeRamz Latsiv YohgatNo ratings yet

- Definition and Purposes of Measurement and EvaluationDocument7 pagesDefinition and Purposes of Measurement and EvaluationJac Flores40% (5)

- Annotated BibliographyDocument92 pagesAnnotated Bibliographybersam05No ratings yet

- DLL SampleDocument31 pagesDLL SampleIlene Grace Sabio ViajeNo ratings yet

- Prudent Lifestyles KSSM BIDocument14 pagesPrudent Lifestyles KSSM BISabsetNo ratings yet

- 11 El Chemistry Lesson PlanDocument3 pages11 El Chemistry Lesson PlankrisnuNo ratings yet

- Final Annotated BibliographyDocument10 pagesFinal Annotated Bibliographyapi-301639691No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Subtracting 2-3 Digits NumbersDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Subtracting 2-3 Digits Numbersshamma almazroeuiNo ratings yet

- Hope 3 - Week 4Document5 pagesHope 3 - Week 4Jane BonglayNo ratings yet

- Senior High School: Daily Lesson LogDocument4 pagesSenior High School: Daily Lesson LogJhimson CabralNo ratings yet

- Competency-Based Education (CBE)Document5 pagesCompetency-Based Education (CBE)Krishna MadhuNo ratings yet

- DLP TRENDS Week 7 - GlobalizationDocument4 pagesDLP TRENDS Week 7 - GlobalizationLawrence Rolluqui100% (1)

- Eds 332 Lesson 2Document10 pagesEds 332 Lesson 2api-297788513No ratings yet

- DLP Eng.-8 - Q2 - NOV. 7, 2022Document4 pagesDLP Eng.-8 - Q2 - NOV. 7, 2022Kerwin Santiago ZamoraNo ratings yet

Carina Granberg

Carina Granberg

Uploaded by

legarces23Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Carina Granberg

Carina Granberg

Uploaded by

legarces23Copyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] On: 21 September 2011, At: 08:19 Publisher:

Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

European Journal of Teacher Education

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cete20

Eportfolios in teacher education 20022009: the social construction of discourse, design and dissemination

Carina Granberg

a a

Department of Interactive Media and Learning, Ume University, Ume, Sweden Available online: 20 Jul 2010

To cite this article: Carina Granberg (2010): Eportfolios in teacher education 20022009: the social construction of discourse, design and dissemination, European Journal of Teacher Education, 33:3, 309-322 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02619761003767882

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-andconditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

European Journal of Teacher Education Vol. 33, No. 3, August 2010, 309322

E-portfolios in teacher education 20022009: the social construction of discourse, design and dissemination

Carina Granberg*

Department of Interactive Media and Learning, Ume University, Ume, Sweden

carina.granberg@educ.umu.se CarinaGranberg 0 300000August 2010 33 2010 & Journal Original Article 0261-9768 Francis European Francis of Teacher 10.1080/02619761003767882(online) CETE_A_477310.sgm Taylor and (print)/1469-5928 Education

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

This paper reports on a study of the experiences of teacher educators in the introduction and development of e-portfolios over an eight-year period from 2002 to 2009 at a Swedish university. The study was conducted with 67 teacher educators in order to investigate how e-portfolios have been discussed, designed, used and disseminated during this period. Research methods involved 25 narrative interviews and a questionnaire that was completed by 42 participants. The theoretical framework of Basil Bernstein, particularly his concepts of classification, framing, educational codes and pedagogical devices, was used to analyse the data. The paper presents a discussion of the contextual circumstances in relation to classification, framing and codes that affect the social construction of e-portfolios. The results point to parallel processes resulting in a variety of discourses and designs of e-portfolios and highlighting the importance of the social construction of e-portfolios across the teacher education faculty, rather than merely their implementation. Keywords: e-portfolio; teacher education; social construction; discourse; design

Introduction The use of e-portfolios in teacher education programmes has increased in recent years in many European and other countries around the world. In addition to pedagogical aims, the driving forces behind this development are often described in terms of the need to meet national standards, address issues of accreditation, or improve quality (Butler 2006; Dysthe and Engelsen 2008; Strudler and Wetzel 2005; Woodward and Nanlohy 2004). Despite the Bologna process, the international trend of introducing e-portfolios into teacher education programmes, and the EU recommendation on using ICT for lifelong learning (European Parliament 2006), the Swedish national agency for higher education has not taken any steps to encourage teacher education institutions to develop the use of these tools. By tradition, Swedish teacher educators are free to choose methods for teaching and assessment; as such the use of e-portfolios depends on initiatives by local advocates and enthusiasts. As a result of one of these local initiatives dating back to 2002, this particular Swedish university has introduced the use of e-portfolios to all student teachers (about 3000 student teachers in total) throughout their general education courses. During the same period of time, different initiatives have been taken by individual teacher educators and teacher teams to use eportfolios in a variety of courses, particularly in distance education courses. In addition to the use of e-portfolios in general education courses, this paper focuses on a selection of pre-service and in-service courses in mathematics, creative studies,

*Email: carina.granberg@educ.umu.se

ISSN 0261-9768 print/ISSN 1469-5928 online 2010 Association for Teacher Education in Europe DOI: 10.1080/02619761003767882 http://www.informaworld.com

310

C. Granberg

literacy and didactics. The study looks into how e-portfolios have been discussed, understood and designed during this period of time. Aim and research questions The aim of the study was to investigate how e-portfolios have been communicated, designed, and disseminated within teacher education courses at this particular university from 2002 to 2009. The questions arising from this study are as follows:

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

How can the design of e-portfolios be described and understood in relation to teacher educators understanding and communication of e-portfolios? How can the dissemination of e-portfolios in the context of teacher education be described and understood?

Background The following section first discusses the relationship between the general purposes and genres of e-portfolios. It then focuses on the context of teacher education, examining e-portfolios as a means of supporting learning and assessment. The section concludes by examining the implementation of e-portfolios.

E-portfolio purposes and genres Portfolios can be categorised into different genres depending on their purpose: as process, reflective or learning portfolios for encouraging student teachers to reflect on their learning process supported by teacher educators formative assessment; as credential or accountability portfolios for assessing student teachers summatively; and finally, as marketing portfolios or showcases for showing student teachers accomplishments to future employers (Barrett and Carney 2005; Butler 2006; Zeichner and Wray 2001). Furthermore, there is no general agreement on these genres. Portfolios can be seen as chameleons that shift their colours depending on their purpose and pedagogical design (Dysthe 2003). For example, Dysthe and Engelson (2008) stated that the Norwegian e-portfolio initiative in teacher education does not correspond to any of these e-portfolio genres, and have described this as a learning and assessment portfolio.

E-portfolio, designed for learning and assessment in teacher education E-portfolios are often related to a constructivist approach to knowledge and learning (Butler 2006). The use of such e-portfolios focuses on the student teachers learning process and knowledge production (rather than reproduction). Student teachers progress can be documented, described and reflected on through an e-portfolio process. Furthermore, a socio-cultural perspective is often adopted in relation to e-portfolio initiatives. Knowledge as well as learning is viewed as situated, social, distributed and mediated, and as a result dependent on participation in communities of practice (Dysthe 2003). The socio-cultural perspective implies communication and feedback from

European Journal of Teacher Education

311

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

others, student teachers as well as teacher educators and e-portfolios afford open environments in which it is easy to publish texts, pictures or multimedia in order to invite teacher educators to provide formative assessments. Studies have shown that the development of e-portfolios can enhance student teachers professional learning process and their ability to reflect on their work (Beck and Bear 2009; Hauge 2006; Mansvelder-Longayroux, Beijaard, and Verloop 2007; Pelliccione and Raisen 2009). The same studies point out that in order to succeed, student teachers need training and support in their reflective work. The importance of teacher presence and supportive feedback during the learning process is highlighted. Hattie and Timperley (2007) conclude that feedback has the most critical influence on students learning. On the other hand, student teachers achievements must be assessed summatively in relation to local or national standards. In addition to focusing the learning process, e-portfolios may serve the assessment of student teachers, and different designs to carry out summative assessments of e-portfolios are presented in the literature (Dysthe and Engelsen 2008; Strudler and Wetzel 2005). E-portfolios are not ideologically independent, and have different purposes when it comes to assessment. Barrett (2007) addressed the conflicting forms of assessments that e-portfolios are meant to serve, such as summative assessing in relation to national or institutional goals on the one hand, and supporting learning through formative assessment on the other. E-portfolios have been caught between the idea of documenting and supporting student teachers learning processes and the demands in terms of assessing their reproduction of knowledge. Initiating the use of e-portfolios in teacher education Developments involving the implementation of portfolios or e-portfolios are described in the international literature, and there are several examples of initiatives at the national level that demand or encourage teacher education institutions to use portfolios to ensure quality standards and/or support student teachers in lifelong learning (Butler 2006; Dysthe and Engelsen 2008; McAllister, Hallam, and Harper 2008; Strudler and Wetzel 2005; Wray 2007). The implementation of e-portfolios in teacher education is described as a complex process that involves, for example, technical, pedagogical and ideological issues, and generates questions related to assessment, ownership and purpose. Barrett and Carney (2005) pointed out that since portfolios can have such different purposes and characteristics there is a need to define what kind of portfolio should be used before the implementation process is initiated. There is reason to regard the genre of e-portfolios as under construction, Goodson (2007) pointed out that we are, as we speak, shaping an emerging genre of e-portfolios. Furthermore, Butler (2006) describes success criteria for introducing e-portfolios as a process of planning during which answers to several what, why and how questions need to be answered. A common understanding of the purpose and design of e-portfolios needs to be established. This points to the importance of a process of construction rather than implementation. Methodology Pedagogical concepts such as e-portfolios cannot be considered objectively; rather, they are interpreted and socially constructed by teacher teams. In turn, individual understandings of these constructs influence the teacher educators experiences and

312

C. Granberg

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

actions. Taking constructivism as an epistemological starting point and aiming to understand the process of development and dissemination of e-portfolios from the teacher educators perspectives, a hermeneutical approach focusing on interpretation and understanding was chosen (Ricoeur 1976). Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used in order to investigate teacher educators understanding of e-portfolios and the circumstances that influenced their way of discussing, creating and engaging them. Narrative interviews, questionnaires, course plans and study guides constitute the data of the study. Thematic content analysis was used to structure the data, after which theory was used to analyse the defined themes through the helix of hermeneutics. A more detailed account of these theories is given in the following section. Methods Ever since the introduction of e-portfolios at this teacher education institution in 2002, they have been organised as a part of the existing Learning Management System (LMS) FirstClass, and through this system the courses and teacher educators using e-portfolios could be identified. During 2008 and 2009, 30 teacher educators, working in these courses and using e-portfolios, were invited to take part in semi-structured interviews. Twenty-five teachers from five departments in the faculty of teacher education volunteered to take part. During these interviews the teachers were asked to describe their understanding of e-portfolios, their experiences in working with them and how the concept had been discussed in the context of teacher education. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. Among the teacher educators who were not invited to the interviews, 60 randomly chosen teacher educators working at the five departments were asked to complete a digital questionnaire seeking similar information; 42 responded. Accordingly, a total of 67 teacher educators are represented in this study. As thematic content analysis was used, the first reading aimed to form themes and to find theoretical concepts suitable for analysing the data. From this reading, the following themes were formulated: the context of teacher education, the discourse of e-portfolios, defined as the teacher educators ways of discussing and understanding e-portfolios (Winther-Jrgensen and Phillips 2000) and the design of e-portfolios in this particular context. In the next step, key sentences and concepts describing the interviewees experiences and understandings of the three themes were selected and analysed. In their narratives, the teacher educators very much related their understanding and designing of e-portfolios to contextual and social aspects. Accordingly, the following theoretical concepts were chosen as the framework. To illuminate the construction of e-portfolios in relation to teacher educators understanding of the concept and teacher education as an educational context, data were analysed in light of Bernsteins theories on educational code, classification and framing (1977, 2000). Furthermore, the theory of social construction (Berger and Luckmann 1966) was used to develop understanding in the process of the construction of e-portfolios in teacher education. A more detailed account of these theories is provided in the following section. Ethical issues All necessary ethical requirements set by the university and as outlined by the Swedish Research Council (2001) were followed in this study. Accordingly, the

European Journal of Teacher Education

313

aspects of beneficence, non-malfeasance, informed consent and anonymity have been taken into account in planning and carrying out the study, and approval for the research design was achieved at the appropriate level of the organisation. The author is employed as an information and communication technology (ICT) teacher educator at the university, but has not taken any active part in the courses concerned. Theoretical framework For the purposes of this study a selection of concepts from the comprehensive theoretical framework of Basil Bernstein has been applied to the analysis. In particular, Bernsteins (1977) concepts of classification, framing and codes are used to analyse the first theme the context of teacher education. Classification concerns the relationship between categories of, for example, agencies, school subjects, teachers, discourse and practices. Depending on the degree of insulation between categories, classification is considered to be strong or weak. Strong classification between school subjects implies that they should be kept apart (e.g., mathematics, chemistry, and history). Weak classification may, for example, initiate the integration of subjects and teachers. Attempts to change the degree of insulation reveal the power relationship on which the classification is based (Bernstein 2000). The concept of framing is about who controls what. For example, weak framing in school contexts gives teachers more freedom to choose content, methods, pace, etc. If the framing is strong, national and/or local regulations leave limited autonomy for teachers to be innovative in their classrooms. Bernstein (1977) also introduced the idea of educational codes. He considered the European way of organising education as strongly classified regarding subjects, teachers and classes, and strongly framed concerning the power of national control of content and methods. Consequently, the educational code could be described as a collection code, where everything should be kept apart. Bernstein identified the opposite an educational code with weak classification and framing, as an integrated code. Additionally, Bernstein (2000) introduced the concept of pedagogical device in order to bring some understanding to the process by which knowledge and competencies from outside the school context become school subjects (e.g., how carpentry becomes woodworking). Bernstein described this process as a re-contextualisation during which a pedagogical discourse of woodworking is created to constitute the basis of the practice of woodworking; in other words, when, what and how the pupils learn. E-portfolio in teacher education is to be considered as a tool or a method, rather than a subject. However, the history of e-portfolios started outside of the context of teacher education (especially in the professional field of schools); and teacher educators and policymakers have brought the concept into teacher education. This process can, according to Bernstein, be understood as a re-contextualisation, during which a pedagogical discourse and design of e-portfolios is socially constructed, affected by the ideology of the new context. The study also draws on the work of Berger and Luckmann (1966), who introduced the idea of social construction, arguing that institutions such as those within the educational system are socially constructed rather than being anything natural and predetermined. In order to describe the process of social construction, Berger and Luckmann (1966) used concepts such as externalisation, objectification,

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

314

C. Granberg

internalisation, legitimation and socialisation. The institutions or educational system manifested in, for example, Bernsteins educational code, are constructed by a social process through which our thinking, understanding and behaviour externalises and objectifies into an object which we take for granted. As humans, we internalise the institution by adapting to appropriate roles, and the educational system becomes legitimised (i.e., explained and justified). The educational system will thus become socially constructed and re-constructed as more people are socialised into the educational context.

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

Results The results are presented thematically: the context of teacher education, the discourse defined as the teacher educators common understanding of e-portfolios, and the design of e-portfolios. The names are fictitious and the quotes are gleaned from interviews as well as questionnaires, and are chosen to be representative of all or an identified group of informants. The context During the main part of this study the teacher education programme at this particular university was organised as a faculty of five departments responsible for their specific fields. The teacher education programmes consist of subject courses, didactic courses suited for different programmes, general education courses that concern all student teachers, and teaching practice. These general education courses are organised as joint courses in which at least two of the five departments collaborate. All informants, that is, interviewees as well as questionnaire respondents, described a situation of strong classification between departments, teacher teams and courses; as Tony expressed: We never meet, and we need to meet. Lisa added: It is only when you share courses with other departments you get an insight into their ideas, besides that you know nothing. Even within departments, a majority of the informants describe the context as somewhat classified. Gwen pointed out that Different teacher educator categories at our department are rather isolated islands. I am not sure about how they teach or assess. With a few exceptions, the informants expressed a lack of formal pedagogic discussions. Ben explained: It is mainly when we plan our courses that we can be involved in pedagogical discussions. There are no national or faculty instructions about how to teach or assess. The formal framing is weak and the teacher educators are free to construct their own ways of teaching. However, a majority of the interviewees pointed out there is an informal framing manifested in the present educational code. Diana said: There is a strong tradition of summative assessment, to focus on final products. Linda added: The ideology of higher education does not pay any attention to processes of creation and learning. Besides focusing on and assessing final products the code could be described as solving assignments in the right way. This educational code, a collection code, is socially constructed and re-constructed by teacher educators as well as student teachers. Peter explained: Student teachers are generally very much focused on concluding the products and then leave them behind. But why shouldnt they, that has been their situation in school for many years. Some student teachers react when the collection code is challenged, as Susan expressed: Some student teachers get

European Journal of Teacher Education

315

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

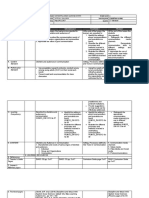

frustrated when I give them challenging feedback. They just want to know if they have passed or failed. The history of e-portfolios in the context of teacher education at this university can be traced back to at least 2002, before which point there had been no tradition of using portfolios, paper or digital. At this time, teacher educators from three departments were assigned to organise an ICT-supported supplementary distance teacher education programme. Each of the teacher educators in this small group had experience working with portfolios, and e-portfolios were chosen as their method for learning and assessment. These teacher educators have continued to develop their use of e-portfolios and their experiences have been useful for developing e-portfolios in shared courses at other departments. At about the same time in 2002, and as an initiative from ICT teacher educators and management, all student teachers on campus were introduced to digital portfolios in their first general educational course. The idea was that these e-portfolios would be used to document the learning process throughout their education. By 2009, in addition to the ordinary campus teacher training programme, one could find the use of eportfolios in pre-service, in-service, distance and campus courses in, for example, creative work, didactics, English, literacy, mathematics, ICT, and masters studies. The discourse In analysing the data one can conclude that there is no common understanding of the concept of e-portfolio. Descriptions vary from a digital archive to a complex method for learning and assessment. However, all informants, that is, interviewees as well as questionnaire respondents, used concepts such as areas, spaces, folders, and rooms that are available, reachable, accessible, and readable to describe eportfolios. Therefore, the lowest common dominator of an e-portfolio discourse describes e-portfolio as a tool, a digital area available to student teachers and their teachers. Among the informants, there was a small group of six teacher educators who did not consider e-portfolios to be anything more than a virtual area. As Mike described: E-portfolio is a digital space, not a pedagogical issue (Figure 1, A). With few exceptions, all interviewees were aware of e-portfolios as a method used in the school context, and two-thirds of the interviewees had former experiences working with portfolios outside teacher education. These experiences merely concern portfolios as showcases in schools, by which pupils showed their parents their achievements, or in professional contexts supporting creative work. Bernstein (2000) pointed out that re-contextualisation is never ideologically free. In this case, when these teacher educators transformed their understanding and experiences of portfolios into higher education the issue of assessment became important since grading students is a significant part of the higher education system. Except for a group of teachers that described e-portfolios solely as a digital space, all interviewees referred to concepts such as summative assessment, control, checking, grading, pass or fail in their understanding of e-portfolios. This widened discourse sees e-portfolios as tools and methods for assessment (Figure 1, B). This way of understanding e-portfolios is in line with the collected educational code, as it is focused on final products that are summatively assessed. Almost half of the interviewees distinguished strongly between e-portfolio as a tool merely for assessment and e-portfolio as a pedagogical method for learning and

316

C. Granberg

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

assessment. When this group of teacher educators explained their idea of e-portfolios they referred to concepts such as lifelong learning, process-based learning, process of knowledge construction gained by integrating assignments, reflecting upon the whole, combining course content, linking or weaving everything together. These teacher educators serve as representative examples. Betsy explained: Portfolios are about weaving together your pre-understanding with new ideas, tasks, reflections, group work etc. to something new, your new understanding. Mary continued: I do not want them to reflect over just a single task, they need to hover like a helicopter and reflect over the whole field, all assignments. Meg added: Nothing in the portfolio should ever lie fallow, all artefacts should be used and re-used. It is like the idea of recycling. These teacher educators contributions to an e-portfolio discourse widen the discourse to correspond to a more integrated educational code that keeps artefacts, processes and knowledge together (Figure 1, C). These three discourses are embedded in one another. Teacher educators who described their understanding of portfolios as a method for learning (Figure 1, C) include portfolios as a way of assessing the student teachers (Figure 1, B) and all teacher educators discussed e-portfolio as an accessible area for artefacts (Figure1, A). The discourse of e-portfolios for learning (Figure 1, C) is socially created within small groups of teacher educators. Their understanding and use of e-portfolios challenges the collection educational code represented by the discourse of understanding e-portfolio as a tool for assessment. This clash reveals the power relationship between these discourses. At some departments the use of e-portfolios for learning and assessment had low status compared to other methods such as final written exams and seminars. As Mary described: When I started to use portfolios in 2002 some colleagues criticised me for being fooled, pointing at portfolios as merely fad and fashion. The construction of e-portfolios began in parallel with the creation of ICT-supported distance courses. The distance education discourse, which employed ICT as a tool for bridging physical distance, overcame some of the resistance towards e-portfolios. Some interviewees described the use of e-portfolios as having spread to the campus courses over time. As Lucy explained: When we introduced the distance courses, e-portfolio became necessary. Susan added: After a while we decided to use e-portfolios in the same way in campus courses, these student teachers have the same need for support.

Figure 1. Three identified borders between e-portfolio discourses: as an archive (A), for summative assessment (B) and as a portfolio for learning (C).

Figure 1. Three identified borders between e-portfolio discourses: as an archive (A), for summative assessment (B) and as a portfolio for learning (C).

European Journal of Teacher Education

317

The design This section presents different designs of e-portfolios in courses and/or programmes in teacher education. In-service, pre-service and distance as well as campus courses are represented as examples that are chosen to give a picture of how the different discourses on e-portfolios have been manifested in the different designs. In order to increase the internal validity, the interviewees narratives describing their e-portfolio designs have been triangulated using course plans, course guides and observations of e-portfolio design in the virtual environments.

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

(a) E-portfolios as an archive: an add-on tool The campus teacher education programmes could serve as one example of a situation in which e-portfolios are considered as an add-on tool, rather than strongly classified within the framing of the course itself (although sometimes being an integrated part). Student teachers who start their training with the first general education course are introduced to working with e-portfolios by ICT teacher educators. The assignments (a1, a2 in Figure 2) have in recent years become all that participating teacher educators have tasked to assess. However, the course itself is not designed to suit e-portfolio as a method for learning. The general educational course includes all students, and the teacher team working with the course consists of many teacher educators from several departments. According to the interviewees, e-portfolios are not discussed as a pedagogical method and the least common understanding of e-portfolios corresponds to a rather narrow discourse that defines e-portfolios as archives. Depending on the student teachers own choices, the courses could be given by different departments. Since the classification between departments, teacher teams and courses is strong, there is neither a common agreement on the use of e-portfolios nor a discourse regulating how to use them. James, who taught a group of second-year-student teachers, said: I did not know that my student teachers had e-portfolios. They [the students] told me when the course started, however I had not prepared any assignments that could suit the use of e-portfolio. Since the framing is weak when it comes to methods it depends very much on the teacher educator if the e-portfolios are used at all in the course and if they are used merely as archives, for assessment or learning.

Figure 2. Successive courses in the campus teacher education program. E-portfolios are introduced in the first general education course and thereafter used when teachers/teacher teams choose to do so ( an = artefact, assignment).

(b) E-portfolios as a tool for assessment Among the in-service and pre-service, campus and distance programme courses, there are examples of e-portfolios used merely for summative assessment. This design is

Figure 2. Successive courses in the campus teacher education programme. E-portfolios are introduced in the first general education course and thereafter used when teachers/teacher teams choose to do so (an = artefact, assignment).

318

C. Granberg

Figure 3. Successive courses within a teacher training programme or single in-service/preservice courses. E-portfolios are used for assessment and work as a main thread throughout the course/program (an = artefact, assignment).

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

built on a discourse that addresses e-portfolio as a tool for assessment. The assignments are adjusted to suit a digital environment involving text, digital pictures and multimedia. The design focuses on final products and the e-portfolios are used as channels for communication between student teachers and assessing teacher educators (Figure 3). The use of assessment portfolios can be seen in single courses as well as in successive courses in programmes. A common characteristic for the teacher teams using e-portfolios throughout a programme is that the teams themselves are relatively small, consisting of, for example, two to six teacher educators who have planned the course/ courses together and discussed how to use the e-portfolios. In the situation where there are successive courses within a programme, at least a small number of these teacher educators worked in all of them, bridging the strong classification between courses and teacher teams. As Pat explained: We decided to work like this, when new teacher educators have come to these courses they have had to adjust to this way of working. The classification between the assignments varies, however it may be considered as rather strong in relation to the situation that the assignments do not relate to one another to any greater extent. However, there are examples of courses in which the student teachers, for example, are assigned to evaluate their learning or integrate earlier assignments into a given task.

Figure 3. Successive courses within a teacher training program or single in-service/pre-service courses. E-portfolios are used for assessment and work as a main thread throughout the course/program ( an = artefact, assignment).

(c) E-portfolio as a method for learning and assessment Among the interviewees there are teacher educators and teacher teams who have used and discussed e-portfolios for a comparatively long time. A discourse on e-portfolios for learning and assessment has been socially created within these teams. These teacher educators have agreed on working towards a more open and integrated educational code. They have chosen to use e-portfolios as a method for learning and assessment, and have created and designed their courses in ways that fitted their portfolio discourse. As Nina explained: If you want the student teachers to focus on their learning process, you need to create assignments that suits the idea: [To look back, reflect and weave everything together]. The following two examples of e-portfolio design show how the method of e-portfolio becomes embedded in the assignments as well as in the tool itself. Example 1. This design can be found among the teacher training programme for creative studies and didactic courses. The design varies, although the common concepts are the greater part. Student teachers start the course by creating individual goals or study plans. During the course the student teachers are asked to keep private diaries/notes/logbooks to document their work. These documents form the basis for the

European Journal of Teacher Education

319

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

Figure 4. One example of successive courses within a teacher training programme or single inservice/pre-service courses. The e-portfolio is designed for learning and assessment throughout the course/programme.

course assignments, which are designed to support the student teachers in describing and reflecting on their work and the learning process, along with their creative work. At the end of the course, all student teachers create a final reflection that covers all of their assignments, including the private diaries, group work, and so on, in relation to their own goals/study plan (Figure 4). The classification between the assignments is very weak, and could easily be described as kept together. As Kate explained: All assignments, literature reflections are integrated. The concept of portfolio is interwoven into the tasks. During the course, teacher educators support their reflective learning process by giving formative feedback. At the end, the teacher educators sum up the student teachers achievements holistically and grade the student teachers work.

Figure 4. One example of successive courses within a teacher training program or single in-service/pre-service courses. The e-portfolio is designed for learning and assessment throughout the course/program.

Example 2. This design was found in some literacy and didactic courses. These teacher educators have chosen to abandon the LMS and use a digital tool for PDP (Personal Development Planning), in which a portfolio is integrated instead. This PDP tool is normally used at the school level. In these courses, the student teachers publish their assignments in their e-portfolios and their reflective and evaluating work in their PDP. Teacher educators formative as well as summative feedback is also put in the PDP. The structure of the PDP supports the student teachers engagement in the portfolio method. The student teachers begin by describing their prior knowledge and creating goals for their learning. This affects how they work with their assignments, which are published in the portfolio. During the course they reflect on and relate the assignments to one another. In the end they finish up by creating self-evaluations in relation to their previous knowledge, goals and achievements. This method can be considered as integrated into the assignments as well as into the tool itself. As Meg explained: It becomes very natural when their work grows to be embedded in the tool. All teacher educators from these teams had a time perspective on the social construction of an e-portfolio discourse. Influences and personal experiences from the 2002 teacher team, described earlier, can be traced in the interviewees narratives. As Judy explained: It has taken us several years because you have to change your way of understanding the learning process, the way you create assignments, the way you work together. This way of blending formative and summative assessments is not seen as problematic by the interviewees advocating e-portfolios for learning and assessment. They do not find this situation unique for e-portfolios. As Amy explained: As a teacher you always have this two-faced role, to support your pupils [formative

Figure 5. One example of an in-service/pre-service course. The e-portfolio and PDP are integrated in the course and design for learning and assessment.

320

C. Granberg

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

Figure 5. One example of an in-service/pre-service course. The e-portfolio and PDP are integrated in the course and design for learning and assessment.

feedback] and assess them [summative feedback]. However in the classroom it is just the normal situation and you do not think about that as a problem. As the results of this study show, the design of e-portfolios at this particular teacher education institution varies widely. One can also find course designs that are under construction to move from one of these categories to another. Furthermore, there are other perspectives on e-portfolios that are discussed. For example, along with the use of e-portfolios for assessment (B) and for learning (C), group portfolios are often used. A majority of the teacher educators who integrate e-portfolios in their courses pointed out the importance of supporting a socially constructed learning process. Ben expressed his wish: I would like them to create their artefacts in front of each other, that is the way we learn together. Discussion This study has illuminated a weakly framed context regarding pedagogical methods that is strongly classified concerning teacher educators, teacher teams, courses, subjects and departments which does not facilitate the social construction of a common understanding of e-portfolios. On the contrary, a variety of local e-portfolio discourses are created and negotiated within small contexts such as teacher teams. Within these teams, teacher educators understanding and former experiences of portfolios contribute to the process of construction. During this re-contextualisation process, transforming portfolios from outside the context of higher education into teacher education, one creates different discourses pointing at e-portfolios as archives and as a method for assessment and/or learning. These discourses, representing different educational codes and pointing at different purposes, are manifested in their specific e-portfolio design. Within this context one can distinguish between e-portfolio genres such as filing portfolio, assessment portfolio and as Dysthe and Engelson (2008) defined, learning and assessment portfolios. The discourse and design of learning and assessment portfolios represent an integrated educational code. This way of focusing on the learning process by weaving assignments and courses together interferes with the traditional way of organising higher education. Teacher educators and student teachers are generally socialised into a collection educational code that requires student teachers to produce, and teacher educators to assess, final products. This traditional collection educational code may be combined with e-portfolios merely for summative assessment, but not with e-portfolios for learning. Teacher educators advocating the use of portfolios for learning find

European Journal of Teacher Education

321

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

themselves in a situation where they need to explain and justify their understanding and use of e-portfolios. It is evident that e-portfolios are not legitimised within the context of teacher education, although a practical need for e-portfolios to bridge physical distances has been shown to facilitate the construction process of e-portfolios. However, the dissemination is dependent on the engagement of individual teacher educators and teacher teams and their struggles with the traditional educational codes. As a result, the wider use of e-portfolios for supporting the learning process has been limited in this teacher education institution. In conclusion it can be seen that e-portfolios are shifting colours like chameleons (Dysthe 2003), depending not only on purpose and design but also teacher educators understanding of e-portfolios, the e-portfolio discourse that teacher teams can agree on, the context itself, the outcome of the struggle between educational codes, and the very course of time. The social construction of e-portfolio discourses and its design is an ongoing process. During this time, one can observe how e-portfolio discourses develop and e-portfolio designs move between e-portfolio genres. This is due in large part to teacher educators having gained experience and increased competencies with ICT. The process of shaping an emerging e-portfolio genre described by Goodson (2007) is truly present. However, the process will likely produce a variety of genres rather than one single e-portfolio genre. This is not a complete concept to be merely implemented but rather can be seen as a concept under construction and struggling for legitimacy.

Notes on contributor

Carina Granberg is a teacher educator and, since 2006, a PhD student at the Department of Interactive Media and Learning at Ume University in Sweden. Her research interests relate to ICT-supported methods for process-based assessments.

References

Barrett, H. 2007. Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: The reflective initiative. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 50, no. 6: 43649. Barrett, H., and J. Carney. 2005. Conflicting paradigms and competing purposes in electronic portfolio development. Educational Assessment. http://electronicportfolios.com/ portfolios.html Beck, R.J., and S.L. Bear. 2009. Teachers self-assessment of reflection skills as an outcome of e-portfolio. In Evaluating electronic portfolios in teacher education, ed. P. Adamy, and N.B. Milman, 122. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. Berger, P.L., and T. Luckmann. 1966. The social construction of reality. New York: Anchor Books. Bernstein, B. 1977. Class, code and control. Towards a theory of educational transmission, Volume 3. London: Routledge. Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. Butler, P. 2006. A review of the literature on portfolios and electronic portfolios. Palmerston North: Massey University College of Education. Dysthe, O. 2003. Dialog, samspel och lrande [Dialogue, teamwork and learning]. Lund: Studentlitteratur. Dysthe, O., and K.S. Engelsen. 2008. Portfolio and assessment in teacher education in Norway: A theory-based discussion of different models in two sites. In Learning and practice. Agency and identities, ed. P. Murphy, and K. Hall, 10219. London: Sage Publications.

322

C. Granberg

Downloaded by [Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile] at 08:19 21 September 2011

European Parliament. 2006. Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council on key competences for lifelong learning. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/ oj/2006/l_394/l_39420061230en00100018.pdf Goodson, F.T. 2007. The electronic portfolio: Shaping an emerging genre. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy 50, no. 6: 4324. Hattie, J., and H. Timperley. 2007. The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research 77, no. 1: 81112. Hauge, T.E. 2006. Portfolios and ICT as means of professional learning in teacher education. Studies in Educational Evaluation 32: 2336. Mansvelder-Longayroux, D., D. Beijaard, and N. Verloop. 2007. The portfolio as a tool for stimulating reflection by student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education 23: 4762. McAllister, L., G. Hallam, and W. Harper. 2008. The e-portfolio as a tool for lifelong learning: Contextualising Australian practice. Paper presented at the Proceedings of International Lifelong Learning Conference, 1619 June, in Yeppoon, Queensland. Pelliccione, L., and G. Raisen. 2009. Promoting the scholarship of teaching through reflective e-portfolios in teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching 35, no. 3: 27181. Ricoeur, P. 1976. Interpretation theory discourse and the surplus of meaning. Forth Worth, TX: Christian University Press. Strudler, N., and K. Wetzel. 2005. The diffusion of electronic portfolios in teacher education: Issues of initiation and implementation. Journal of Research on Teacher Education 3, no. 4: 41133. Swedish Research Council. 2001. Ethical principles of research in humanistic and social science. http://www.vr.se Winther-Jrgensen, M., and L. Phillips. 2000. Diskursanalys som teori och metod. Lund: Studentliteratur. Woodward, H., and P. Nanlohy. 2004. Digital portfolios in pre-service teacher education. Assessment in Education 11, no. 2: 16778. Wray, S. 2007. Electronic portfolios in a teacher education program. E-learning 4, no. 1: 4051. Zeichner, K., and S. Wray. 2001. The teaching portfolio in US teacher education programs: what we know and what we need to know. Teaching and Teacher Education 17: 61321.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Levesque On Historical Literacy Winter 2010Document5 pagesLevesque On Historical Literacy Winter 2010legarces23No ratings yet

- Barton. Elementary Students' Ideas About Historical EvidenceDocument25 pagesBarton. Elementary Students' Ideas About Historical Evidencelegarces23No ratings yet

- School HistoryDocument7 pagesSchool Historylegarces23No ratings yet

- Micro Analysis and The Construction of The SocialDocument12 pagesMicro Analysis and The Construction of The Sociallegarces23No ratings yet

- 1.MIL 1. Introduction To MIL (Part 1) - Communication, Media, Information, Technology Literacy, and MILDocument35 pages1.MIL 1. Introduction To MIL (Part 1) - Communication, Media, Information, Technology Literacy, and MILMargerie Fruelda50% (2)

- DLP DIASS Q2 Week A - Settings, Processes and Tools in CommunicationDocument14 pagesDLP DIASS Q2 Week A - Settings, Processes and Tools in CommunicationKatrina BalimbinNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Educomp Smart ClassDocument4 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Educomp Smart ClassSantosh KmNo ratings yet

- Work SampleDocument32 pagesWork Sampleapi-356623029No ratings yet

- Sced 3311 Teaching Philosophy Final DraftDocument7 pagesSced 3311 Teaching Philosophy Final Draftapi-333042795No ratings yet

- Innovating Pedagogy 2022Document61 pagesInnovating Pedagogy 2022pacoperez2008No ratings yet

- Tle Carpentry DLLDocument36 pagesTle Carpentry DLLJessica Rebodos100% (1)

- Ubd Social StudiesDocument8 pagesUbd Social Studiesapi-253205044No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 3 Grade 5Document6 pagesLesson Plan 3 Grade 5api-496650728No ratings yet

- Ped 9 Content Module 9Document16 pagesPed 9 Content Module 9Arline Hinampas BSED-2204FNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Arithmetic SequencesDocument35 pagesMathematics Arithmetic SequencesElmer B. Gamba100% (1)

- Week5 Quarter-2-DLl DLPDocument5 pagesWeek5 Quarter-2-DLl DLPRHODORA GAJOLEN100% (2)

- Art Science Integration Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesArt Science Integration Lesson Planapi-237170589No ratings yet

- Review Writing Lesson Plan PDFDocument3 pagesReview Writing Lesson Plan PDFapi-662176377No ratings yet

- PLC ProjectDocument9 pagesPLC Projectapi-531717294No ratings yet

- LP Cot1 2021 2022 PeDocument4 pagesLP Cot1 2021 2022 PeHannah Katreena Joyce JuezanNo ratings yet

- M1 - L2 - 1 - The CentepedeDocument1 pageM1 - L2 - 1 - The CentepedeRamz Latsiv YohgatNo ratings yet

- Definition and Purposes of Measurement and EvaluationDocument7 pagesDefinition and Purposes of Measurement and EvaluationJac Flores40% (5)

- Annotated BibliographyDocument92 pagesAnnotated Bibliographybersam05No ratings yet

- DLL SampleDocument31 pagesDLL SampleIlene Grace Sabio ViajeNo ratings yet

- Prudent Lifestyles KSSM BIDocument14 pagesPrudent Lifestyles KSSM BISabsetNo ratings yet

- 11 El Chemistry Lesson PlanDocument3 pages11 El Chemistry Lesson PlankrisnuNo ratings yet

- Final Annotated BibliographyDocument10 pagesFinal Annotated Bibliographyapi-301639691No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Subtracting 2-3 Digits NumbersDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Subtracting 2-3 Digits Numbersshamma almazroeuiNo ratings yet

- Hope 3 - Week 4Document5 pagesHope 3 - Week 4Jane BonglayNo ratings yet

- Senior High School: Daily Lesson LogDocument4 pagesSenior High School: Daily Lesson LogJhimson CabralNo ratings yet

- Competency-Based Education (CBE)Document5 pagesCompetency-Based Education (CBE)Krishna MadhuNo ratings yet

- DLP TRENDS Week 7 - GlobalizationDocument4 pagesDLP TRENDS Week 7 - GlobalizationLawrence Rolluqui100% (1)

- Eds 332 Lesson 2Document10 pagesEds 332 Lesson 2api-297788513No ratings yet

- DLP Eng.-8 - Q2 - NOV. 7, 2022Document4 pagesDLP Eng.-8 - Q2 - NOV. 7, 2022Kerwin Santiago ZamoraNo ratings yet