Professional Documents

Culture Documents

VILLARMINO, Gladys T. BBG - AC417 Sarbanes-Oxley Act

VILLARMINO, Gladys T. BBG - AC417 Sarbanes-Oxley Act

Uploaded by

Helena BorjalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

VILLARMINO, Gladys T. BBG - AC417 Sarbanes-Oxley Act

VILLARMINO, Gladys T. BBG - AC417 Sarbanes-Oxley Act

Uploaded by

Helena BorjalCopyright:

Available Formats

VILLARMINO, Gladys T. BBG AC417 SarbanesOxley Act The SarbanesOxley Act of 2002 (Pub.L. 107-204, 116 Stat.

. 745, enacted July 30, 2002), also known as the 'Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act' (in the Senate) and 'Corporate and Auditing Accountability and Responsibility Act' (in the House) and commonly called SarbanesOxley, Sarbox or SOX, is a United States federal law which set new or enhanced standards for all U.S. public company boards, management and public accounting firms. It is named after sponsors U.S. Senator Paul Sarbanes (D-MD) and U.S. Representative Michael G. Oxley (R-OH). The bill was enacted as a reaction to a number of major corporate and accounting scandals including those affecting Enron, Tyco International, Adelphia, Peregrine Systems and WorldCom. These scandals, which cost investors billions of dollars when the share prices of affected companies collapsed, shook public confidence in the nation's securities markets. The act contains 11 titles, or sections, ranging from additional corporate board responsibilities to criminal penalties, and requires the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to implement rulings on requirements to comply with the law. Harvey Pitt, the 26th chairman of the SEC, led the SEC in the adoption of dozens of rules to implement the SarbanesOxley Act. It created a new, quasi-public agency, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, or PCAOB, charged with overseeing, regulating, inspecting and disciplining accounting firms in their roles as auditors of public companies. The act also covers issues such as auditor independence, corporate governance, internal control assessment, and enhanced financial disclosure. Outlines SarbanesOxley contains 11 titles that describe specific mandates and requirements for financial reporting. Each title consists of several sections, summarized below. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) Title I consists of nine sections and establishes the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, to provide independent oversight of public accounting firms providing audit services ("auditors"). It also creates a central oversight board tasked with registering auditors, defining the specific processes and procedures for compliance audits, inspecting and policing conduct and quality control, and enforcing compliance with the specific mandates of SOX. Auditor Independence Title II consists of nine sections and establishes standards for external auditor independence, to limit conflicts of interest. It also addresses new auditor approval requirements, audit partner rotation, and auditor reporting requirements. It restricts auditing companies from providing non-audit services (e.g., consulting) for the same clients. Corporate Responsibility Title III consists of eight sections and mandates that senior executives take individual responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of corporate financial reports. It defines the interaction of external auditors and corporate audit committees, and specifies the responsibility of corporate officers for the accuracy and validity of corporate financial reports. It enumerates specific limits on the behaviors of corporate officers and describes specific forfeitures of benefits and civil penalties for non-compliance. For example, Section 302 requires that the company's "principal officers" (typically the Chief Executive Officer and Chief Financial Officer) certify and approve the integrity of their company financial reports quarterly. Enhanced Financial Disclosures Title IV consists of nine sections. It describes enhanced reporting requirements for financial transactions, including off-balance-sheet transactions, pro-forma figures and stock transactions of corporate officers. It

requires internal controls for assuring the accuracy of financial reports and disclosures, and mandates both audits and reports on those controls. It also requires timely reporting of material changes in financial condition and specific enhanced reviews by the SEC or its agents of corporate reports. Analyst Conflicts of Interest Title V consists of only one section, which includes measures designed to help restore investor confidence in the reporting of securities analysts. It defines the codes of conduct for securities analysts and requires disclosure of knowable conflicts of interest. Commission Resources and Authority Title VI consists of four sections and defines practices to restore investor confidence in securities analysts. It also defines the SECs authority to censure or bar securities professionals from practice and defines conditions under which a person can be barred from practicing as a broker, advisor, or dealer. Studies and Reports Title VII consists of five sections and requires the Comptroller General and the SEC to perform various studies and report their findings. Studies and reports include the effects of consolidation of public accounting firms, the role of credit rating agencies in the operation of securities markets, securities violations and enforcement actions, and whether investment banks assisted Enron, Global Crossing and others to manipulate earnings and obfuscate true financial conditions. Corporate and Criminal Fraud Accountability Title VIII consists of seven sections and is also referred to as the Corporate and Criminal Fraud Accountability Act of 2002. It describes specific criminal penalties for manipulation, destruction or alteration of financial records or other interference with investigations, while providing certain protections for whistleblowers. White Collar Crime Penalty Enhancement Title IX consists of six sections. This section is also called the White Collar Crime Penalty Enhancement Act of 2002. This section increases the criminal penalties associated with white-collar crimes and conspiracies. It recommends stronger sentencing guidelines and specifically adds failure to certify corporate financial reports as a criminal offense. Corporate Tax Returns Title X consists of one section. Section 1001 states that the Chief Executive Officer should sign the company tax return. Corporate Fraud Accountability Title XI consists of seven sections. Section 1101 recommends a name for this title as Corporate Fraud Accountability Act of 2002. It identifies corporate fraud and records tampering as criminal offenses and joins those offenses to specific penalties. It also revises sentencing guidelines and strengthens their penalties. This enables the SEC to resort to temporarily freezing transactions or payments that have been deemed "large" or "unusual".

Enron Enron Corporation was an American energy, commodities, and services company based in Houston, Texas. Before its bankruptcy on December 2, 2001, Enron employed approximately 22,000 staff and was one of the world's leading electricity, natural gas, communications, and pulp and paper companies, with claimed revenues of nearly $101 billion in 2000.[1] Fortune named Enron "America's Most Innovative Company" for six consecutive years. At the end of 2001, it was revealed that its reported financial condition was sustained substantially by institutionalized, systematic, and creatively planned accounting fraud, known as the "Enron scandal". Enron has since become a popular symbol of willful corporate fraud and corruption. The scandal also brought into questions the accounting practices and activities of many corporations throughout the United States and was a factor in the creation of the SarbanesOxley Act of 2002. The scandal also affected the wider business world by causing the dissolution of the Arthur Andersen accounting firm. Enron filed for bankruptcy protection in the Southern District of New York in late 2001 and selected Weil, Gotshal & Manges as its bankruptcy counsel. It emerged from bankruptcy in November 2004, pursuant to a court-approved plan of reorganization, after one of the biggest and most complex bankruptcy cases in U.S. history. A new board of directors changed the name of Enron to Enron Creditors Recovery Corp., and focused on reorganizing and liquidating certain operations and assets of the pre-bankruptcy Enron.[3] On September 7, 2006, Enron sold Prisma Energy International Inc., its last remaining business, to Ashmore Energy International Ltd. (now AEI). Enron Complex in Downtown Houston Enron traces its roots to the Northern Natural Gas Company, which was formed in 1932, in Omaha, Nebraska. It was reorganized in 1979 as the leading subsidiary of a holding company, InterNorth which was a highly diversified energy and energy related products company. Internorth was a leader in natural gas production, transmission and marketing as well as natural gas liquids and an innovator in the plastics industry. It owned Peak Antifreeze and developed EVAL resins for food packaging. In 1985, it bought the smaller and less diversified Houston Natural Gas. The separate company initially named itself "HNG/InterNorth Inc.", even though InterNorth was the nominal survivor. It built a large and lavish headquarters complex with pink marble in Omaha (dubbed locally as the "Pink Palace"), that was later sold to Physicians Mutual. However, the departure of ex-InterNorth and first CEO of Enron Corp Samuel Segnar six months after the merger allowed former HNG CEO Kenneth Lay to become the next CEO of the newly merged company. Lay soon moved the company's headquarters to Houston after swearing to keep it in Omaha and began to thoroughly re-brand the business. Lay and his secretary, Nancy McNeil, originally selected the name "Enteron" (possibly spelled in camelcase as "EnterOn"), but, when it was pointed out that the term approximated a Greek word referring to the intestines, it was quickly shortened to "Enron". The final name was decided upon only after business cards, stationery, and other items had been printed reading Enteron. Enron's "crooked E" logo was designed in the mid-1990s by the late American graphic designer Paul Rand. Rand's original design included one of the elements of the E in yellow which disappeared when copied or faxed. This was quickly replaced by a green element. Almost immediately after the move to Houston, Enron began selling off key assets such as Northern PetroChemicals and took on silent partners in Enron CoGeneration, Northern Border Pipeline and Transwestern Pipeline and became a less diversified company. Early financial analysts said Enron was swimming in debt and the sale of key operations would not solve the problems. Misleading financial accounts In 1990, Enron Finance CEO Jeff Skilling hired Andrew Fastow, who was well acquainted with the burgeoning deregulated energy market Skilling wanted to exploit. In 1993, Fastow set to work establishing numerous limited liability special purpose entities (common business practice); however, it also allowed Enron to place liability so that it would not appear in its accounts, allowing it to maintain a robust and generally growing stock price and thus keeping its critical investment grade credit ratings.

Enron was originally involved in transmitting and distributing electricity and natural gas throughout the United States. The company developed, built, and operated power plants and pipelines while dealing with rules of law and other infrastructures worldwide. Enron owned a large network of natural gas pipelines, which stretched ocean to ocean and border to border including Northern Natural Gas, Florida Gas Transmission, Transwestern Pipeline company and a partnership in Northern Border Pipeline from Canada. The states of California, New Hampshire and Rhode Island had already passed power deregulation laws by July 1996, the time of Enron's proposal to acquire Portland General Electric. In 1998, Enron moved into the water sector, creating the Azurix Corporation, which it part-floated on the New York Stock Exchange in June 1999. Azurix failed to break into the water utility market, and one of its major concessions, in Buenos Aires, was a large-scale money-loser. After the move to Houston, many analysts[who?] criticized the Enron management as swimming in debt. The Enron management pursued aggressive retribution against its critics, setting the pattern for dealing with accountants, lawyers, and the financial media. Enron grew wealthy due largely to marketing, promoting power, and its high stock price. Enron was named "America's Most Innovative Company" by Fortune for six consecutive years, from 1996 to 2001. It was on the Fortune's "100 Best Companies to Work for in America" list in 2000, and had offices that were stunning in their opulence. Enron was hailed by many, including labor and the workforce, as an overall great company, praised for its large long-term pensions, benefits for its workers and extremely effective management until its exposure in corporate fraud. The first analyst to publicly disclose Enron's financial flaws was Daniel Scotto, who in August 2001 issued a report entitled "All Stressed-up And No Place To Go", which encouraged investors to sell Enron stocks and bonds at any and all costs. As was later discovered, many of Enron's recorded assets and profits were inflated or even wholly fraudulent and nonexistent. One example of fraudulent records was in 1999 when Enron promised to payback Merrill Lynch & Co investment with interest in order to show profit on its books. Debts and losses were put into entities formed "offshore" that were not included in the firm's financial statements, and other sophisticated and arcane financial transactions between Enron and related companies were used to take unprofitable entities off the company's books. Its most valuable asset and the largest source of honest income, the 1930s-era Northern Natural Gas, was eventually purchased back by a group of Omaha investors, who moved its headquarters back to Omaha, and is now a unit of Warren Buffett's MidAmerican Energy Holdings Corp. NNG was put up as collateral for a $2.5 billion capital infusion by Dynegy Corporation when Dynegy was planning to buy Enron. When Dynegy looked closely at Enron's books, they backed out of the deal and fired their CEO, Chuck Watson. The new chairman and head CEO, the late Daniel Dienstbier, had been president of NNG and an Enron executive at one time and was forced out of Enron by Ken Lay. Dienstbier was an acquaintance of Warren Buffett. NNG continues to be profitable today.

You might also like

- 11 Titles of SoxDocument2 pages11 Titles of SoxchetandpsNo ratings yet

- D75 14Document8 pagesD75 14JorgeCalvoLara100% (2)

- Oxley Act of 2002 (Pub.L. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745, Enacted July 30, 2002), Also Known As The 'Public - Oxley, Sarbox or SOX, Is A United StatesDocument21 pagesOxley Act of 2002 (Pub.L. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745, Enacted July 30, 2002), Also Known As The 'Public - Oxley, Sarbox or SOX, Is A United StatesposttoamitNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes - Oxley Act: United States Federal LawDocument8 pagesSarbanes - Oxley Act: United States Federal LawJayanta ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes Oxley ActDocument3 pagesSarbanes Oxley ActRadical-thinker WeluweluNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes Oxley Act: - Oxley Act of 2002, Also Known As The 'Public Company AccountingDocument4 pagesSarbanes Oxley Act: - Oxley Act of 2002, Also Known As The 'Public Company AccountingRavi MarwahNo ratings yet

- Brief History of SOXDocument4 pagesBrief History of SOXHemant Sudhir WavhalNo ratings yet

- Aj Ibañez - Assignment 2Document19 pagesAj Ibañez - Assignment 2AJ Louise IbanezNo ratings yet

- Aj Ibañez - Assignment 2Document19 pagesAj Ibañez - Assignment 2AJ Louise IbanezNo ratings yet

- SOXDocument15 pagesSOXRafael BazaniNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 10Document5 pagesAssignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 10Haris MunirNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes Oxley ActDocument17 pagesSarbanes Oxley Actglenndso100% (2)

- Case StudyDocument17 pagesCase StudyAmit RajoriaNo ratings yet

- The Enron Scandal - A Case Study in Business Ethics and Corporate GovernanceDocument4 pagesThe Enron Scandal - A Case Study in Business Ethics and Corporate GovernanceShiney BenjaminNo ratings yet

- Examples of Agency ProblemsDocument3 pagesExamples of Agency ProblemsdaleNo ratings yet

- Ais Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002wfaDocument19 pagesAis Sarbanes Oxley Act of 2002wfaLeslie Ann ArguellesNo ratings yet

- Basic Facts of Sox LawDocument2 pagesBasic Facts of Sox LawnamuNo ratings yet

- Securities and Exchange Commission: Sarbanes-Oxley ActDocument10 pagesSecurities and Exchange Commission: Sarbanes-Oxley ActLedayl MaralitNo ratings yet

- Sox ADocument2 pagesSox ARicha RekhiNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 2Document4 pagesAssignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 2Haris MunirNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, 2019) - Section 102 Requires Public Accounting Firms To Register WithDocument4 pagesSarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, 2019) - Section 102 Requires Public Accounting Firms To Register WithKinsey ProficeNo ratings yet

- SoxDocument16 pagesSoxArmand MauricioNo ratings yet

- Enron Case StudyDocument6 pagesEnron Case Studyali goharNo ratings yet

- Operation Audit Case AnalysisDocument3 pagesOperation Audit Case AnalysisEu RiNo ratings yet

- 11 - Chapter 6 PDFDocument24 pages11 - Chapter 6 PDFkamalm06No ratings yet

- Eneron Scandal and Sox ActDocument4 pagesEneron Scandal and Sox ActA ANo ratings yet

- Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 Jadeen Service Hampton University 2014 MBA 315 3/5/2014Document12 pagesSarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 Jadeen Service Hampton University 2014 MBA 315 3/5/2014jadeen serviceNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes-Oxley ActDocument9 pagesSarbanes-Oxley ActalinactriveniNo ratings yet

- Learning Unit 1.4 Corporate Governance - International DevelopmentsDocument3 pagesLearning Unit 1.4 Corporate Governance - International DevelopmentsbbhatlaneNo ratings yet

- Acct 201 - Chapter 4Document24 pagesAcct 201 - Chapter 4Huy TranNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes Oxley ActDocument3 pagesSarbanes Oxley ActRomnick PascuaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Governance Additional NotesDocument6 pagesLesson 1 Governance Additional NotesCarmela Tuquib RebundasNo ratings yet

- Health South Corp - The First Test of Sarbanes OxleyDocument27 pagesHealth South Corp - The First Test of Sarbanes OxleyShaun1906No ratings yet

- Case Study Session 1 Group 7Document4 pagesCase Study Session 1 Group 7rifqi salmanNo ratings yet

- Managerial FinanceDocument4 pagesManagerial Financeinnies duncanNo ratings yet

- Presented by Syed Kashif Shah (Group Leader) Group Members Kashif Ali, M.Hamid Waqar Khan Bba 7Document22 pagesPresented by Syed Kashif Shah (Group Leader) Group Members Kashif Ali, M.Hamid Waqar Khan Bba 7Jemila SatchiNo ratings yet

- Enron Scandal PresentationDocument11 pagesEnron Scandal PresentationYujia JinNo ratings yet

- Corporate America and SarbanesDocument2 pagesCorporate America and SarbanesMohammad Nowaiser MaruhomNo ratings yet

- CH 8Document4 pagesCH 8Eng Eman HannounNo ratings yet

- Enron Case History and Major Issues SummaryDocument6 pagesEnron Case History and Major Issues Summaryshanker23scribd100% (1)

- Week 9 ACC 290 Capstone Discussion QuestionDocument4 pagesWeek 9 ACC 290 Capstone Discussion Questiontking000No ratings yet

- Part 1Document108 pagesPart 1Thirnugnanasampandar ArulananthasivamNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of EnronDocument22 pagesThe Rise and Fall of EnronDhanwantri SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of The Internal Control in Audit Process For Small Business in General Santos CityDocument2 pagesThe Effect of The Internal Control in Audit Process For Small Business in General Santos Citybelinda dagohoyNo ratings yet

- Enron Corporation Was An American EnergyDocument7 pagesEnron Corporation Was An American EnergyMae AroganteNo ratings yet

- Internal ControlsDocument40 pagesInternal ControlsARIEL FRITZ CACERESNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Sarbanes Oxley ActDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Sarbanes Oxley Actegw0a18w100% (1)

- Discussion Computer AccountingDocument4 pagesDiscussion Computer AccountingArceeNo ratings yet

- 5457 The Lawyer As Gatekeeper Is There A Need For A Whistleblowing Securities Lawyer Recent Developments in The Us and AustraliaDocument47 pages5457 The Lawyer As Gatekeeper Is There A Need For A Whistleblowing Securities Lawyer Recent Developments in The Us and Australiainfra lawNo ratings yet

- Implications of The SarbanesDocument5 pagesImplications of The SarbanesArcha ShajiNo ratings yet

- Audit of Accounts, Processes, and Assertions: SectionDocument6 pagesAudit of Accounts, Processes, and Assertions: SectionCryptic LollNo ratings yet

- Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) ActDocument20 pagesSarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Actjanaki ramanNo ratings yet

- Pencegahan Kecurangan Dalam Pelaporan KeuanganDocument31 pagesPencegahan Kecurangan Dalam Pelaporan KeuanganBintang Yudha Dwi KurniaNo ratings yet

- SERVAN Assignment#1Document6 pagesSERVAN Assignment#1Faith Jilliane P. ServanNo ratings yet

- Corporate and Accounting Scandals Enron WorldcomDocument1 pageCorporate and Accounting Scandals Enron Worldcom張雅媞No ratings yet

- 10 - SoxDocument2 pages10 - Soxreina maica terradoNo ratings yet

- Enron Scandal: Managing Finance and Financial DecisionsDocument10 pagesEnron Scandal: Managing Finance and Financial Decisions'Sabur-akin AkinadeNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 9Document3 pagesAssignment On Sarbanes Oaxley Act 9Haris MunirNo ratings yet

- Business Organizations: Outlines and Case Summaries: Law School Survival Guides, #10From EverandBusiness Organizations: Outlines and Case Summaries: Law School Survival Guides, #10No ratings yet

- Piercing the Corporate Veil: A Comprehensive Guide for AttorneysFrom EverandPiercing the Corporate Veil: A Comprehensive Guide for AttorneysNo ratings yet

- Catalogue 2019Document450 pagesCatalogue 2019AntonNo ratings yet

- Using Powerpoint Effectively in Your PresentationDocument5 pagesUsing Powerpoint Effectively in Your PresentationEl Habib BidahNo ratings yet

- ISBB CompilationDocument6 pagesISBB CompilationElla SalesNo ratings yet

- Overview of Flexfields 58987177.doc Effective Mm/dd/yy Page 1 of 24 Rev 1Document24 pagesOverview of Flexfields 58987177.doc Effective Mm/dd/yy Page 1 of 24 Rev 1sudharshan79No ratings yet

- New Record TDocument2 pagesNew Record Tapi-309280225No ratings yet

- Multimedia Chapter 1 and 2Document22 pagesMultimedia Chapter 1 and 2tsegab bekeleNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 - Futher PractiseDocument34 pagesUnit 5 - Futher PractiseNgọc Hoa LêNo ratings yet

- Saint Mary's University: School of Health and Natural SciencesDocument7 pagesSaint Mary's University: School of Health and Natural SciencesEj AgsaldaNo ratings yet

- Disaster Mana BooksDocument20 pagesDisaster Mana BooksSupraja_Prabha_8353No ratings yet

- Job Opportunities Sydney 7082017Document10 pagesJob Opportunities Sydney 7082017Dianita CorreaNo ratings yet

- SpaceX Response To DISH Re Mobile Platforms (6!8!22)Document6 pagesSpaceX Response To DISH Re Mobile Platforms (6!8!22)michaelkan1No ratings yet

- D D D D D D: Description/ordering InformationDocument13 pagesD D D D D D: Description/ordering InformationWelleyNo ratings yet

- Stabilization of Dispersive Soil by Blending PolymDocument4 pagesStabilization of Dispersive Soil by Blending Polymnagy_andor_csongorNo ratings yet

- SUN - MOBILITY - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2022-23 - Financial Statement - XMLDocument109 pagesSUN - MOBILITY - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2022-23 - Financial Statement - XMLTanishq ChourishiNo ratings yet

- CRDB Bank Job Opportunities Customer ExperienceDocument4 pagesCRDB Bank Job Opportunities Customer ExperienceAnonymous FnM14a0No ratings yet

- BS 2782-10 Method 1005 1977Document13 pagesBS 2782-10 Method 1005 1977Yaser ShabasyNo ratings yet

- Excel Project AssignmentDocument5 pagesExcel Project AssignmentJayden RinquestNo ratings yet

- Recalls 10 - Np2Document6 pagesRecalls 10 - Np2Nova Clea BoquilonNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment Report Pinagtigasan KinderDocument12 pagesAccomplishment Report Pinagtigasan KinderMay Anne AlmarioNo ratings yet

- CSEC Physics P2 2015 JuneDocument18 pagesCSEC Physics P2 2015 JuneBill BobNo ratings yet

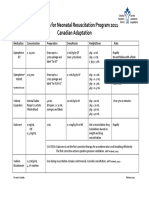

- Medications For Neonatal Resuscitation Program 2011 Canadian AdaptationDocument1 pageMedications For Neonatal Resuscitation Program 2011 Canadian AdaptationrubymayNo ratings yet

- VBA Water 6.09 Temperature Pressure Relief Valve Drain LinesDocument2 pagesVBA Water 6.09 Temperature Pressure Relief Valve Drain LinesgaryNo ratings yet

- Edma Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesEdma Lesson Planapi-662165409No ratings yet

- Nihongo Lesson FL 1Document21 pagesNihongo Lesson FL 1Lee MendozaNo ratings yet

- Feeder Protection REF615: Product GuideDocument40 pagesFeeder Protection REF615: Product Guidenzinga DHA SantralNo ratings yet

- Fire Catalog Alco-LiteDocument14 pagesFire Catalog Alco-LiteForum PompieriiNo ratings yet

- Printable Article Synthetic Materials Making Substances in The LabDocument2 pagesPrintable Article Synthetic Materials Making Substances in The LabJoshua BrewerNo ratings yet

- Nakshtra Swami and BhramanDocument12 pagesNakshtra Swami and Bhramansagar_m26100% (1)

- Action ResearchDocument6 pagesAction Researchbenita valdezNo ratings yet