Professional Documents

Culture Documents

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

648 viewsAl Farabi Translation

Al Farabi Translation

Uploaded by

scholar786Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- (M. A. Draz) Introduction To The Qur'an (Book4You)Document172 pages(M. A. Draz) Introduction To The Qur'an (Book4You)faisalnamah100% (1)

- Al Farabi Book of LettersDocument27 pagesAl Farabi Book of LettersAdrian Mucileanu100% (1)

- Fusus Al-Hikam - Pearls of Wisdom - by Ibn-Al-ArabiDocument144 pagesFusus Al-Hikam - Pearls of Wisdom - by Ibn-Al-Arabiscparco100% (1)

- Al-Farabi and The Reconciliation of Plato and AristotleDocument11 pagesAl-Farabi and The Reconciliation of Plato and AristotlejanmalolepszyNo ratings yet

- Aristotelian Curriculum PDFDocument21 pagesAristotelian Curriculum PDFhobojoe9127No ratings yet

- Dietrich - Von Freiberg - Markus Lorenz Führer Treatise On The Intellect and The Intelligible - TractDocument272 pagesDietrich - Von Freiberg - Markus Lorenz Führer Treatise On The Intellect and The Intelligible - TractdsajdjsajidsajiNo ratings yet

- The Three Bodies, Soul SplitsDocument6 pagesThe Three Bodies, Soul Splitsphilalethes2456100% (1)

- Philosophy and Theology in The Islamic Culture: Al-Fārābī's de ScientiisDocument11 pagesPhilosophy and Theology in The Islamic Culture: Al-Fārābī's de ScientiiscdmemfgambNo ratings yet

- Pseudo Theology of Aristotle Structure and CompositionDocument36 pagesPseudo Theology of Aristotle Structure and CompositionFrancis Gladstone-Quintuplet100% (1)

- Edited by Jon McGinnis, Interpreting Avicenna, Science and Philosophy in Medieval PhilosophyDocument280 pagesEdited by Jon McGinnis, Interpreting Avicenna, Science and Philosophy in Medieval PhilosophyAllan NevesNo ratings yet

- Saleh Historiography of TafsirDocument36 pagesSaleh Historiography of TafsirMazen El Makkouk100% (1)

- Abd Al-Latif Al-Baghdadi MetaphysicsDocument390 pagesAbd Al-Latif Al-Baghdadi MetaphysicsKhalilou BouNo ratings yet

- Avicenna On The OntologyDocument774 pagesAvicenna On The OntologymauricioamarNo ratings yet

- Samar Attar - The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment - Ibn Tufayl's Influence On Modern Western Thought (2007)Document195 pagesSamar Attar - The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment - Ibn Tufayl's Influence On Modern Western Thought (2007)robsclaroNo ratings yet

- Gabriel's Wing - Muhammad IqbalDocument3 pagesGabriel's Wing - Muhammad IqbalZeghaider100% (1)

- The Possibility of The Universe in Farabi Ibn Sina and MaimonidesDocument33 pagesThe Possibility of The Universe in Farabi Ibn Sina and MaimonidescolinpaulNo ratings yet

- Razi - Book of Philosophic Life (Butterworth)Document31 pagesRazi - Book of Philosophic Life (Butterworth)Docteur Larivière100% (1)

- The Nature and Scope of Arabic Philosophical Commentary PDFDocument44 pagesThe Nature and Scope of Arabic Philosophical Commentary PDFimreadingNo ratings yet

- Endress - Formation of Terminology in Arabic PhilosophyDocument24 pagesEndress - Formation of Terminology in Arabic PhilosophyYunis IshanzadehNo ratings yet

- The Rational Tradition in Islam - Muhsin MahdiDocument25 pagesThe Rational Tradition in Islam - Muhsin MahdiSamir Abu Samra100% (3)

- Some Arabic Translations of Aristotle's MetaphysicsDocument35 pagesSome Arabic Translations of Aristotle's MetaphysicsLulamonNo ratings yet

- Ibn Qutaybas Understanding of Quranic BrevityDocument140 pagesIbn Qutaybas Understanding of Quranic Brevityshiraaaz100% (1)

- Ibn Rushd's MetaphysicsDocument113 pagesIbn Rushd's MetaphysicsCapsLock610No ratings yet

- Bekir Karliga - Al-Farabi - A Civilization Philosopher-КазНУ (2016)Document96 pagesBekir Karliga - Al-Farabi - A Civilization Philosopher-КазНУ (2016)Haris ImamovićNo ratings yet

- Islamic Philosophy, Science, Culture, and Religion: Studies in Honor of Dimitri GutasDocument36 pagesIslamic Philosophy, Science, Culture, and Religion: Studies in Honor of Dimitri GutasNikola TatalovićNo ratings yet

- Gutas 2012. Avicenna The Metaphysics of The Rational Soul PDFDocument9 pagesGutas 2012. Avicenna The Metaphysics of The Rational Soul PDFUmberto MartiniNo ratings yet

- Mohammed Arkoun - Rethinking Islam - ReviewDocument4 pagesMohammed Arkoun - Rethinking Islam - ReviewAfthab EllathNo ratings yet

- Ilm Al Wad A Philosophical AccountDocument19 pagesIlm Al Wad A Philosophical AccountRezart Beka100% (1)

- Al-Farabi - The Conditions of CertitudeDocument8 pagesAl-Farabi - The Conditions of CertitudejbnhmNo ratings yet

- The Beginnings of Mystical Philosophy in Al-Andalus Ibn Masarra and His Epistle On ContemplationDocument53 pagesThe Beginnings of Mystical Philosophy in Al-Andalus Ibn Masarra and His Epistle On ContemplationceudekarnakNo ratings yet

- CreedsDocument56 pagesCreedsHailé SzelassziéNo ratings yet

- Edward William Lane's Lexicon - Volume 1 - Page 001 À 100Document100 pagesEdward William Lane's Lexicon - Volume 1 - Page 001 À 100Serge BièvreNo ratings yet

- Intellect and Intuition - Their Relationship From The Islamic Perspective (Seyyed Hossein Nasr) PDFDocument9 pagesIntellect and Intuition - Their Relationship From The Islamic Perspective (Seyyed Hossein Nasr) PDFIsraelNo ratings yet

- Cornford 1903 - Plato and OrpheusDocument14 pagesCornford 1903 - Plato and OrpheusVincenzodamianiNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Knowledge, Active Intellect and Intellectual Memory in Avicenna's Kitab Al-Nafs and Its Aristotelian BackgroundDocument54 pagesIntellectual Knowledge, Active Intellect and Intellectual Memory in Avicenna's Kitab Al-Nafs and Its Aristotelian BackgroundOmid DjalaliNo ratings yet

- PhA 119 - Theophrastus On First Principles (Known As His Metaphysics) PDFDocument532 pagesPhA 119 - Theophrastus On First Principles (Known As His Metaphysics) PDFPhilosophvs Antiqvvs100% (1)

- Jdmiii Thesis Auc-FinalDocument108 pagesJdmiii Thesis Auc-FinalGamirothNo ratings yet

- Book - Ibn Taymiyya's Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism, Jon HooverDocument282 pagesBook - Ibn Taymiyya's Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism, Jon HooverAbu Shu'aibNo ratings yet

- The Teleological Ethics of Fakhr Al-Dīn Al-RāzīDocument3 pagesThe Teleological Ethics of Fakhr Al-Dīn Al-RāzīhozienNo ratings yet

- Al FarabiDocument9 pagesAl Farabinshahg1No ratings yet

- Murabit Ahmad Faal Eulogy2Document8 pagesMurabit Ahmad Faal Eulogy2HelmiHassanNo ratings yet

- The Hanbali School and Sufism - Dr. George MakdisiDocument12 pagesThe Hanbali School and Sufism - Dr. George Makdisisyed quadriNo ratings yet

- Dictionary of Islamic Philosophical TermsDocument126 pagesDictionary of Islamic Philosophical Termswww.alhassanain.org.englishNo ratings yet

- The Arabic, Hebrew and Latin Reception of Avicenna's MetaphysicsDocument34 pagesThe Arabic, Hebrew and Latin Reception of Avicenna's MetaphysicsPilar Herraiz Oliva100% (1)

- Qutb Al Din Al ShiraziDocument20 pagesQutb Al Din Al ShiraziSoak Kaos100% (1)

- Averroes - ''Prooemium'' To Aristotle's PhysicsDocument14 pagesAverroes - ''Prooemium'' To Aristotle's PhysicsGiordano BrunoNo ratings yet

- Strauss, Leo - How To Study Medieval PhilosophyDocument10 pagesStrauss, Leo - How To Study Medieval PhilosophyAlejandra PatiñoNo ratings yet

- Maimonides Treatise On LogicDocument95 pagesMaimonides Treatise On Logicshamati100% (1)

- Beyond Atoms and Accidents: Fakhr Al-Dīn Al-Rāzī and The New Ontology of Postclassical KalāmDocument56 pagesBeyond Atoms and Accidents: Fakhr Al-Dīn Al-Rāzī and The New Ontology of Postclassical KalāmemoizedNo ratings yet

- Yahya Michot, An Important Reader of Al-Ghazālī - Ibn TaymiyyaDocument30 pagesYahya Michot, An Important Reader of Al-Ghazālī - Ibn Taymiyyammehmetsahin123No ratings yet

- Fusus Al-Hikam Caner DagliDocument227 pagesFusus Al-Hikam Caner DagliS⸫Ḥ⸫R80% (5)

- Aristotelian Cosmology and Arabic Astron PDFDocument19 pagesAristotelian Cosmology and Arabic Astron PDFanie bragaNo ratings yet

- Mehdi Mohaghegh Hermann Landolt Ed Collected Papers On Islamic Philosophy and Mysticism PDFDocument336 pagesMehdi Mohaghegh Hermann Landolt Ed Collected Papers On Islamic Philosophy and Mysticism PDFalghazalianNo ratings yet

- BookofKeystotheKindgom SijistaniDocument63 pagesBookofKeystotheKindgom SijistaniMuhammad Ali KhalilNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Aspects of Repetition in The QuranDocument14 pagesRhetorical Aspects of Repetition in The QuranMohsin Khaleel0% (1)

- Patterns of Contemplation: Ibn 'Arabi, Abdullah Bosnevi and the Blessing-Prayer of EffusionFrom EverandPatterns of Contemplation: Ibn 'Arabi, Abdullah Bosnevi and the Blessing-Prayer of EffusionNo ratings yet

- The Path Vol 1 - William JudgeDocument439 pagesThe Path Vol 1 - William JudgeMark R. JaquaNo ratings yet

- Syarah Diwan Imam Asy Syafi I Untaian Mutiara Hikamah Dan Petunjuk Hidup Imam Asy Syafi I Muhammad Ibrahim Salim Full Chapter Download PDFDocument58 pagesSyarah Diwan Imam Asy Syafi I Untaian Mutiara Hikamah Dan Petunjuk Hidup Imam Asy Syafi I Muhammad Ibrahim Salim Full Chapter Download PDFlexebepat100% (1)

- Yusuf Estes and The QuranDocument57 pagesYusuf Estes and The QuranMaktabah AlFawaaidNo ratings yet

- Training in Difficult Choices: 5 Public Policy Case Studies From SlovakiaDocument101 pagesTraining in Difficult Choices: 5 Public Policy Case Studies From Slovakiascholar786No ratings yet

- Classical Islamic Educa Vrs US EduDocument14 pagesClassical Islamic Educa Vrs US Eduscholar786No ratings yet

- Education in Medieval Bristol and GloucestershireDocument20 pagesEducation in Medieval Bristol and Gloucestershirescholar786100% (1)

- MethodologyPoliticalTheory PDFDocument28 pagesMethodologyPoliticalTheory PDFscholar786No ratings yet

- Historical Development of Muslim MutazilismDocument4 pagesHistorical Development of Muslim Mutazilismscholar786No ratings yet

- Ibn Abi Shaybah MusannafDocument573 pagesIbn Abi Shaybah Musannafscholar786No ratings yet

- The First Musannaf of Ibn Abi ShaybahDocument552 pagesThe First Musannaf of Ibn Abi Shaybahscholar786No ratings yet

- Can Creativity Be LearnedDocument4 pagesCan Creativity Be Learnedscholar786No ratings yet

- Fifth ElementDocument10 pagesFifth Elementscholar786No ratings yet

- A Phenomenological Case Study of A Principal Leadership - The InflDocument292 pagesA Phenomenological Case Study of A Principal Leadership - The Inflscholar786No ratings yet

- Lughaat Al Quran G A ParwezDocument736 pagesLughaat Al Quran G A Parwezscholar786No ratings yet

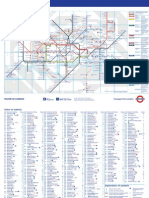

- Standard Tube MapDocument2 pagesStandard Tube Mapscholar786No ratings yet

- DeFilippo - Curiositas and The Platonism of Apuleius' Golden Ass PDFDocument23 pagesDeFilippo - Curiositas and The Platonism of Apuleius' Golden Ass PDFGaby La ChettiNo ratings yet

- Plato Overview Theory of Being or Reality (Metaphysics) : Richard L. W. Clarke LITS2306 Notes 02CDocument6 pagesPlato Overview Theory of Being or Reality (Metaphysics) : Richard L. W. Clarke LITS2306 Notes 02CMatheus de BritoNo ratings yet

- Adrian Pirtea - The Origin of Passions in Neoplatonic and Early Christian Thought - Porphyry of Tyre and Evagrius PonticusDocument4 pagesAdrian Pirtea - The Origin of Passions in Neoplatonic and Early Christian Thought - Porphyry of Tyre and Evagrius PonticusSeb AstianNo ratings yet

- LogicDocument63 pagesLogicMArieMigallenNo ratings yet

- Aertsen - What Is Most Fundamental Beginnings Transcendetal Philosophy PDFDocument16 pagesAertsen - What Is Most Fundamental Beginnings Transcendetal Philosophy PDFjeisonbukowskiNo ratings yet

- The Chaldean Oracles of Zoroaster, Hekate's Couch, and Platonic Orientalism in Psellos and Plethon PDFDocument22 pagesThe Chaldean Oracles of Zoroaster, Hekate's Couch, and Platonic Orientalism in Psellos and Plethon PDFMau Oviedo100% (3)

- The Mystical Temple of GodDocument111 pagesThe Mystical Temple of GodKaye LolitaNo ratings yet

- Voegelin's History of Political IdeasDocument212 pagesVoegelin's History of Political Ideasquintus14100% (3)

- T.S. Eliot, Dante and The Idea of EuropeDocument248 pagesT.S. Eliot, Dante and The Idea of EuropeMila BoschiNo ratings yet

- A Homily by Elder Ephraim of PhilotheouDocument9 pagesA Homily by Elder Ephraim of Philotheoujosephpang777No ratings yet

- Armstrong - Some Advantages of PolytheismDocument6 pagesArmstrong - Some Advantages of PolytheismDirk CloeteNo ratings yet

- Values Education Topic #1 FaithDocument13 pagesValues Education Topic #1 FaithRechil TorregosaNo ratings yet

- Highlight: On OffDocument6 pagesHighlight: On OffAndrey TenovNo ratings yet

- Sadr Al-Din Qunawi The Texts Al-NususDocument40 pagesSadr Al-Din Qunawi The Texts Al-NususLeah Stropos100% (1)

- Module 2Document10 pagesModule 2LA Marie100% (1)

- To Be Man Is To Know (Frithjof Schuon) PDFDocument5 pagesTo Be Man Is To Know (Frithjof Schuon) PDFIsraelNo ratings yet

- Fides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonDocument23 pagesFides Et Ratio As The Perpetual Journey of Faith and ReasonClarensia AdindaNo ratings yet

- Broadie, 2001, Soul and Body in Plato and DescartesDocument15 pagesBroadie, 2001, Soul and Body in Plato and DescartesVioleta MontielNo ratings yet

- Who Is The Demiurge According To PlutarchDocument14 pagesWho Is The Demiurge According To PlutarchallyonionNo ratings yet

- Eric VoegelinDocument438 pagesEric VoegelinBronzeAgeManNo ratings yet

- Dragas - Theology and Science, The Anthropic PrincipleDocument15 pagesDragas - Theology and Science, The Anthropic PrincipleLeeKayeNo ratings yet

- The Secret Teachings of All AgesDocument723 pagesThe Secret Teachings of All AgesTrice AugustinNo ratings yet

- Nature and Necessity in Spinozas Philosophy Garrett Full ChapterDocument67 pagesNature and Necessity in Spinozas Philosophy Garrett Full Chapterjohn.gray829100% (10)

- Locus ClassicusDocument2 pagesLocus Classicuspseudo78No ratings yet

- The Corpse Bride:Thinking With Nigredo by Reza NegarestaniDocument17 pagesThe Corpse Bride:Thinking With Nigredo by Reza NegarestaniJZ201050% (2)

- PLUTARCH AND PAGAN MONOTHEISM Frederick Brenk PDFDocument16 pagesPLUTARCH AND PAGAN MONOTHEISM Frederick Brenk PDFjusrmyrNo ratings yet

Al Farabi Translation

Al Farabi Translation

Uploaded by

scholar786100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

648 views271 pagesCopyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

648 views271 pagesAl Farabi Translation

Al Farabi Translation

Uploaded by

scholar786Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 271

Farabi`s Virtuous City and the Plotinian World Soul:

A New Reading oI Farabi`s Mabadi' Ara' Ahl Al-Madina Al-Fadila

By

Gina M. Bonelli

Institute oI Islamic Studies

McGill University, Montreal

August, 2009

'A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial IulIillment oI the

requirements oI the degree oI Doctor oI Philosophy.

Gina Marie Bonelli 2009

AcInowledgements

I would liIe to thanI above all my advisors ProIessor Eric Ormsby and

ProIessor Robert WisnovsIy Ior all oI their worI in helping me to Iinish this

dissertation. I cannot even begin to estimate the hours spent by ProIessor

Ormsby reading and editing my worI, but, based on the copies that he sent bacI

to me stained by his inIamous red pen, perhaps I could Iathom a guess. I would

also liIe to thanI ProIessor Donald P. Little Ior providing me with the invaluable

advice that 'sometimes it is enough to asI the questions. Since leaving the

institute, due to a Iamily illness, I have great appreciation Ior the Irequent emails

and occasional phone calls Irom ProIessor Uner Turgay and Kirsty McKinnon,

which varied Irom a progress report to a Iriendly hello, but reminded me that I

was still a part oI the Institute. OI course, a huge thanI you to Salwa Ferahian,

Wayne St. Thomas, and Steve Millier at the Institute oI Islamic Studies Library

Ior always promptly getting the inIormation and articles to me that I desperately

needed. I would also liIe to mention my undying gratitude Ior the support given

to me Irom my Iamily and Iriends. I cannot even begin to thanI Rebecca

Williams who actually volunteered to read my worI and provide insightIul

advice during the pivotal moments oI research and writing. And most oI all I

would liIe to thanI my brother Joseph Ior letting me stay at his home while I

Iinished this dissertation and oI course Ior his inIinite patience and Iindness Ior

listening to my incessant discussions oI Plotinus, Augustine, and Farabi and their

worIs.

ii

Abstract

Happiness (saadah) materializes as the ultimate goal oI man in Abu Nasr

Muhammad b. Muhammad b. TarIhan al- Farabi`s Mabadi' Ara' Ahl Al-Madina

Al-Fadila (Principles oI the Views oI the Citizens oI the Best State). But

happiness, i.e., happiness in this liIe and happiness in the aIterliIe, is only

attainable by the virtuous citizen. The prevailing academic vision oI Farabi`s

Virtuous City essentially can be placed into two categories: either it is an ideal

as Iound in Plato`s Republic or it is an actual city that has been Iounded or will

be established at some time in the Iuture. The diIIiculty with both oI these

interpretations is that they limit who can attain happiness. I will argue that we

must examine Farabi`s Virtuous City in a diIIerent light. I will show that

Farabi`s Virtuous City is comparable to the Plotinian World Soul in which it is

the genus oI all souls and it is the place to which all souls strive to return, and

there attain happiness. As a result, it can be argued that Farabi`s Virtuous City

is a city that exists in the intelligible world; it contains both citizens that reside

within the city and citizens that reside in the material world. Through a

comparison oI Farabi`s Virtuous City with the Plotinian World Soul, we shall see

that Farabi`s Virtuous City is not unliIe Aurelius Augustine`s City oI God,

which is also a city that exists in the intelligible world, and has citizens within

both this city and here on earth. By comparing the relevant texts oI Plotinus,

Augustine, and Farabi, it becomes possible to illustrate how Farabi, liIe

Augustine, utilized the Plotinian Triple Hypostases (The One, Nous, and the

World Soul) in order to answer the ultimate questions: Why does man desire

iii

happiness? How does man attain this happiness? And most importantly, where

can man attain this happiness?

Farabi tells us that only virtuous citizens will achieve happiness. This

leaves us with unanswered questions. II all souls derive Irom the Virtuous City,

then why do they not all return? What deIines a virtuous citizen? How does one

become a virtuous citizen? These are questions that must be answered in the

material world, by us, Farabi`s readers. Farabi`s Al-Madina Al-Fadila, liIe

Augustine`s De Civitate Dei, clearly outlines a speciIic system oI Inowledge and

a speciIic way oI liIe; in this way, both Farabi and Augustine provide the criteria

by which human beings can become virtuous citizens and citizens oI the City oI

God. Plotinus` concept oI the undescended soul may also provide us with

another way oI looIing at these virtuous citizens and citizens oI the City oI God,

in that these citizens become aware oI the higher part oI their soul and assimilate

themselves to the intelligible world. These citizens must live in the material

world, i.e., in the non-virtuous cities and the City oI Man, but they too can be

citizens oI those cities that exist in the intelligible world. Farabi and Augustine

leave us with a choice to maIe: oI which city will we become citizens?

iv

Resume

Le bonheur (saadah) apparat comme l`objectiI ultime de l`homme dans

(Mabadi' Ara' Ahl Al-Madina Al-Fadila) Idees des habitants de la cite vertueuse

de Muhammad b. Muhammad b. TarIhan al-Farabi. Mais le bonheur, c.-a-d., le

bonheur dans cette vie et le bonheur dans la vie apres la mort, est seulement

possible pour le citoyen vertueux. La vision courante de la cite vertueuse de

Farabi propose essentiellement seulement deux categories: ou c`est un ideal

comme trouve dans Le Republique de Platon ou c`est une cite reelle qui a ete

Iondee ou qui sera etablie a un moment donne dans l`avenir. La diIIiculte avec

tous les deux interpretations est qu`ils limitent le nombre de ceux qui peuvent

atteindre le bonheur. Pour cette raison, je soutiendrai que nous devons examiner

la cite vertueuse de Farabi dans une lumiere diIIerente. Je montrerai que la cite

vertueuse de Farabi est comparable a l`me du monde de Plotinus dans laquelle

c`est le genre de toutes les mes et c`est l`endroit auquel toutes les mes tchent

de rentrer: l`atteindre Iait le bonheur. Ainsi, on peut soutenir que la cite

vertueuse de Farabi est une cite qui existe dans le monde intelligible; elle

contient a la Iois les citoyens qui resident dans la cite et aussi les citoyens qui

resident dans le monde materiel. Par une comparaison de la cite vertueuse de

Farabi avec l`me du monde de Plotinus nous verrons que la cite vertueuse de

Farabi n`est pas diIIerente de la cite de Dieu de Aurelius Augustine; a aussi est

une cite qui existe dans le monde intelligible, et qui a des citoyens et dans cette

cite et ici sur terre. En comparant les texts justicatiIs de Plotinus, Augustine, et

Farabi, il devient possible d`illustrer comment Farabi, comme Augustine, a

v

utilise les Hypostases Triples de Plotinus (L`un, Nous, et L`me du monde) aIin

de repondre aux questions Iinales: Pourquoi l`homme desire-t-il le bonheur?

Comment l`homme atteint-il ce bonheur? Et d`une maniere plus importante, ou

peut l`homme atteindre ce bonheur?

Farabi nous indique que seulement les citoyens vertueux realiseront le

bonheur. Ceci nous laisse avec des questions sans reponse. Si toutes les mes

derivent de la cite vertueuse, alors pourquoi ne Iont-elles pas toutes le retour?

Que deIinit un citoyen vertueux? Comment Iait un devenu un citoyen vertueux?

Ce sont ces questions qui doivent tre adressees dans le monde materiel, par

nous, les lecteurs de Farabi. Al-Madina Al-Fadila de Fa ra bi , comme De Civitate

Dei de Augustine, decrit clairement un systeme speciIique de la connaissance et

une mode de vie speciIique; dans cette Iaon, Farabi et Augustine Iournissent les

criteres par lesquels les tres humains peuvent devenir les citoyens vertueux et

les citoyens de la cite de Dieu. Le concept de l`me non descendue de Plotinus

peut-tre nous Iournit une autre Iaon ere de regarder ces citoyens vertueux et

ces citoyens de la cite de Dieu, par laquelle, ces citoyens se rendent compte de la

partie plus elevee de leur me et s`assimilent au monde intelligible. Ces citoyens

doivent vivre dans le monde materiel, c.-a-d., dans les cites non-vertueuses et la

cite de l`homme, mais ils peuvent eux aussi tre les citoyens de cette cite qui

existent dans le monde intelligible. Fa rabi et Augustine nous donnent un choix a

Iaire: de quelle cite devenons-mns des citoyens?

vi

Table oI Contents.

AcInowledgements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii.

Abstract . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii-iv.

Resume . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . v-vi.

List oI Abbreviations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . x-xi.

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1-15.

Part One

Chapter One: Historiography. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16-58.

I. Historiography oI Arabic Philosophy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16-27.

I. a. Gutas` Critique oI Leo Strauss. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18-22.

I. b. Politics and Neoplatonism. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22-27.

II. The Neoplatonic Problem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27-42.

II.a. The Counter-Argument oI Dominic O`Meara . . . . . . . . . . . . . .29-37.

II.b. The Role oI Plotinus. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37-42.

III. Historiography oI Farabi`s Virtuous City. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42-48.

IV. Neoplatonic Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48-55.

V. Biographical InIormation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55-58.

Part Two

Part Two Introduction: On the Attainment oI Happiness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59-61.

Chapter Two: Farabi On the Attainment oI Happiness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62-101.

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .62-63.

I. Farabi`s Plato. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63-65.

vii

II. Farabi`s Aristotle. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65-70.

III. Farabi On Happiness. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70-91.

IV. Comparison oI Farabi`s Active Intellect and the Plotinian Nous. 91-

101.

V. Philosophy and Religion as Paths to Happiness. . . . . . . . . . . . . 101-

105.

Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105-107.

Chapter Three: Augustine On the Attainment oI Happiness. . . . . . . . . . 108-128.

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .108-109.

I. Augustine`s Quest Ior Happiness. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .110-114.

II. Adam as the Plotinian World Soul. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .114-119.

III. Augustine and Plotinus` Use oI Logos. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .120-123.

IV. Augustine and Plotinus on Contemplation and Action. . . . . . 123-124.

V. Augustine on the Return oI the Soul. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124-126.

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 127-128.

Part Two Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129-130.

Part Three

Part Three Introduction: The Virtuous City and its Citizens. . . . . . . . . . 131-136.

Chapter Four: Cities in the Intelligible World. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .137-173.

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137-138.

I. The Cosmos oI Plotinus. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .138-140.

II. The Cosmos oI Augustine. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 140-147.

III. The Cosmos oI Farabi. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .147-152.

IV. The Ruler oI Farabi`s Virtuous City. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .152-154.

viii

V. Farabi`s Virtuous City as the Plotinian World Soul. . . . . . . . . 154-172.

Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .172-173.

Chapter Five: Citizenship. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174-208.

Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .174-175.

I. Two Levels oI Existence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .175-181.

II. Augustine`s DeIinition oI a Citizen. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .181-191.

III. Farabi`s DeIinition oI a Citizen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192-206.

III. a. Academic Discussion oI the Required Knowledge oI Virtuous

Citizens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 198-201.

III. b. Required Actions oI Virtuous Citizens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 202-206.

Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .206-208.

Chapter Six: Virtuous Citizens Residing in the City oI Man. . . . . . . . . .209-228.

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209-211.

I. Augustine`s City oI God: an Early City?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .212-215.

II. Citizens oI the City oI God Residing in the City oI Man. . . . .215-216.

III. Farabi`s Virtuous Citizens Residing in Non-Virtuous Cities. . 217-

227.

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .227-228.

Part Three Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .229-232.

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .233-238.

Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 239-260.

ix

List oI Abbreviations

ConI.: Augustine, Aurelius. ConIessions. Translated by Henry ChadwicI. New

YorI: OxIord University Press, 1991.

City: Augustine, The City oI God Against the Pagans. Cambridge Texts in

the History oI Political Thought. Edited and Translated by R.W. Dyson.

New YorI: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

AIlatun: Fa rabi, Kitab FalsaIat AIlatun wa-Ajza `uha wa-Maratib Ajza`iha Min

Awwaliha Ila AIhiriha (The Philosophy oI Plato) in De Platonis

Philosophia. Edited by Franz Rosenthal and Richard Walzer. London:

Catholic Press, 1943. Translated with an introduction by Muhsin Mahdi.

In Philosophy oI Plato and Aristotle. New YorI: Cornell University

Press, 1969.

Aristutalis: Farabi, FalsaIat Aristu t alis (The Philosophy oI Aristotle) Ed.

Muhsin Mahdi. Beirut: Dar Majallat Shi`r, 1961. Translated with an

introduction by Muhsin Mahdi. In Philosophy oI Plato and Aristotle.

New YorI: Cornell University Press, 1969.

Fusul: Farabi, Fusul Muntazaah (Selected Aphorisms). Ed. Fauzi Najjar.

Beirut, 1971. Edited and Translated with an introduction by Charles E.

Butterworth. In AlIarabi: The Political Writings, "Selected Aphorisms"

and Other Texts. Ithaca: New YorI, 2001. Edited and Translated

by D. M. Dunlop. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1961.

Madinah: Farabi, Maba di' Ara' Ahl Al-Madina Al-Fadilah (Principles oI the

Views oI the Citizens oI the Best State). Edited and Translated by

Richard Walzer. OxIord: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Millah: Fa ra bi , Kitab al-Millah wa Nusus UIhra (BooI oI Religion). Edited

with an introduction and notes by Muhsin Mahdi. Beirut: Dar al-

Mashriq, 1968. Edited and Translated with an introduction by Charles E.

Butterworth. ). In AlIarabi: The Political Writings, "Selected

Aphorisms" and Other Texts. Ithaca: New YorI, 2001. Translated by

Lawrence V. Berman. Available through the Translation Clearing House.

OIlahoma: OIlahoma State University Catalog reIerence number: A-30-

55b.

Siyasah: Fa rabi, Kitab al-Siyasah al-Madaniyyah al-Mulaqqab bi-Maba di` al-

Mawjudat (Principles oI Beings or the Six Principles, or the Political

Regime). Edited by Fauzi Najjar. Beirut: Catholic Press, 1964. Partial

translation by Fauzi M. Najjar in Medieval Political Philosophy: A

SourcebooI. Edited by Ralph Lerner and Muhsin Mahdi. New YorI:

The Free Press, 1963. Translated by Therese-Anne Druart

x

xi

available through the Translation Clearing House.

OIlahoma: OIlahoma State University. Catalog reIerence number: A-

30-50d.

Tahsil: Farabi, Tah s i l al-Saa dah (The Attainment oI Happiness). Hyderabad,

1345 A.H. Translated with an introduction by Muhsin Mahdi. In

Philosophy oI Plato and Aristotle. New YorI: Cornell University Press,

1969.

Enn.: Plotinus. The Enneads. Translated by A.H. Armstrong, 7 vols.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1966-1988.

AlIarabi: Political Philosophy: Mahdi, Muhsin. AlIarabi and the Foundation oI

Islamic Political Philosophy. With a Ioreword by Charles E. Butterworth.

Chicago: The University oI Chicago Press, 2001.

'Al-Farabi: Islamic Philosophy: Mahdi, Muhsin. 'Al-Farabi and the

Foundation oI Islamic Philosophy. In Islamic Philosophy and

Mysticism. Ed. Parviz Morewedge. Delmar: Caravan, 1981.

Introduction

In this dissertation I will argue that the varying interpretations oI Abu

Nasr Muhammad b. Muhammad b. TarIhan al-Farabi`s |870-950 CE| Mabadi'

Ara' Ahl Al-Madina Al-Fadila (Principles oI the Views oI the Citizens oI the

Best State)

1

have tended to ignore the most Iundamental aspect oI his thought.

This is the central importance he accords to the notion oI happiness (saadah).

2

By examining his Madinah with this notion Iirmly in mind, however, it becomes

possible to provide a coherent account oI his thought. The interpretations

oIIered to date by modern scholars diIIer widely and are oIten mutually

exclusive; and yet, it is just these conIlicting interpretations which continue to

determine the very questions we asI oI Farabi`s text. Such Iorced questions

have at times created a seeming gulI oI divergent views. Here it will be argued

that a new approach is needed. To accomplish that, however, we must begin by

examining the established arguments.

A case in point is Joshua Parens, who begins his latest worI with the

claim that 'now more than at any time Ior centuries, AlIarabi, a tenth-century

1

Al-Fa ra bi , Maba di' A ra ' Ahl Al-Madi na Al-Fa d ila Principles oI the Views oI the Citizens oI the

Best State, translated by Richard Walzer (OxIord: Clarendon Press, 1985). The text as a whole

will be reIerred to as Madi nah while the discussion oI the city itselI will be reIerred to as the

Virtuous City throughout this paper.

2

According to Lane, the word saadah denotes 'prosperity, good Iortune, happiness, or Ielicity oI

a man; with respect to religion and with respect to worldly things: it is oI two Iinds relating to

the world to come and relating to the present world.Edward William Lane, An Arabic-English

Lexicon 8 vols. (Beirut: Librairie du Liban, 1968), 1362. It should be noted, saadah is the

Arabic word used in the Arabic translation oI Aristotle`s Nicomachean Ethics

Ior the GreeI

term eudaimonia. See Al-AIhlaq (Ethica Nicomachea. Arabic) translated by Ish a q ibn H unayn,

edited by Abd al-Rahman Badawi, (WaIalat al-Matbuat: Kuwayt, 1979), 57. The Arabic

Version oI the 'Nicomachean Ethics edited by Anna A. AIasoy and Alexander Fidora with an

introduction and annotated translation by Douglas M. Dunlop (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 1095a 18I./

1129b 18/ 1152b 6/1153b 11/1169b 29/ 1176a 31I.

1

Muslim political philosopher, is especially timely.

3

Parens primarily Iocuses on

Farabi`s Tahsil al-Saadah (Attainment oI Happiness) wherein Farabi 'envisions

the IulIillment oI Islam`s ambition to spread Islam, as the virtuous religion, to

the inhabited world.

4

Parens claims:

In his Attainment oI Happiness, AlIarabi extrapolates Irom

insights that Plato developed in the Republic. In the Republic, Socrates

envisions a perIectly just city (polis) as one in which all citizens are

devoted solely to the common good. The harm done to the private good

oI most citizens in that city is Iamiliar to most undergraduates. AlIarabi

uses that insight and applies it to his own setting. He wonders what it

would taIe Ior Islam to achieve its ambition to rule the world justly. He

argues that it would require that not only every nation but also every city

within every nation should be virtuous. Furthermore, to be truly just, the

rulers oI each nation would need to be philosopher-Iings, and each city

would need to have its own peculiar adaptations or imitations oI

philosophy suited to its particular climate and locale. In other words, a

virtuous world regime would require a multiplicity oI virtuous religions

to match the multiplicity oI virtuous nations.

5

Parens is actually arguing that the Tah s i l is essentially a cautionary tale. Indeed

he claims that 'AlIarabi does not intend this world regime to be a realistic or

even an ideal plan. Rather, he seeIs to persuade his reader that the eIIort to

establish a just world regime is an impossibly high, even iI a noble, goal.

6

Unquestionably, Parens is correct in his assertion that Farabi is extremely

signiIicant in light oI the political atmosphere oI the present day. The

IulIillment oI Islam`s ambition to spread Islam, as 'the virtuous religion, to the

inhabited world is indeed an important point to examine. These statements lead

us to thinI oI another worI oI Farabi`s which seems to be as essential, iI not

3

Joshua Parens, An Islamic Philosophy oI Virtuous Religions: Introducing AlIarabi (New YorI:

State University oI New YorI Press, 2006), 1.

4

Ibid.

5

Ibid., 2.

6

Ibid., 2.

2

more so; this is Farabi`s Madinah. Following Parens, we, too, asI: is Farabi`s

Virtuous City necessarily an Islamic city? And does Fa ra bi envision the

Virtuous City as a city that is supposed to be spread across the inhabited world?

The answer to these questions must be no. Nonetheless, by even asIing these

questions we are limiting the way that we perceive Farabi`s Virtuous City. Is

our vision oI the Virtuous City predetermined? I intend to show that Farabi`s

Virtuous City has been predominantly recognized by scholars to be either an

ideal city, a city that is only discussed in theory, as Iound in Plato`s Republic or

an actual city that has been Iounded or will be established at some time in the

Iuture. Nevertheless, both oI these interpretations conIlict with what Farabi

conveys about the attainment oI happiness. It will be argued here that we must

change the way we examine Farabi`s Virtuous City.

While there are numerous interpretations oI Madinah, none is wholly

satisIactory because each ignores Farabi`s concept oI happiness (saadah), that

is, happiness on earth and ultimate happiness, in which happiness is attained in

the aIterliIe. Paul WalIer notes that a single Iocal point in Farabi`s thought has

not been Iound; thus, all suppositions about Farabi and his worI are provisional.

7

However, happiness appears to be the paramount consideration in his Madinah

and in a number oI other worIs. But which happiness is the most important?

Muhsin Mahdi notes that in Tahsil, worldly happiness is only mentioned once,

thereby implying that it may not be as crucial as ultimate happiness. However,

7

Paul E. WalIer, 'Philosophy oI Religion in Al-Fara bi, Ibn Si na and Ibn T uIayl in Reason and

Inspiration in Islam: Theology, Philosophy and Mysticism Essays in Honour oI Hermann

Landolt edited by Todd Lawson (New YorI: I.B. Tauris Publishers, 2005), 89.

3

Mahdi argues too that Farabi could not have simply overlooIed what most

Muslims believed to be a prerequisite oI ultimate happiness, i.e., happiness on

earth.

8

Patricia Crone claims that 'true happiness, according to al-Farabi, was

intellectual and moral perIection in this world and immortality oI the rational

soul in the next.

9

This claim suggests that happiness on earth is the attainment

oI the necessary perIections, while ultimate happiness is attained in the next liIe.

II Crone`s claim is correct, then earthly happiness appears to be vital in the

achievement oI ultimate happiness, but ultimate happiness is oI the utmost

importance. Farabi seems to be more concerned about the soul and its Iinal

destination in the intelligible world than the soul`s place in the ever changing

sublunary or material world. The intelligible world is the world that can be

perceived by man`s intellect alone and not by sense perception.

10

The

intelligible world is the metaphysical, ethereal, incorporeal, or immaterial

8

Muhsin Mahdi, AlIarabi and the Foundation oI Islamic Political Philosophy, with a Ioreword by

Charles E. Butterworth (Chicago: The University oI Chicago Press, 2001), 173-174.

9

Patricia Crone, God`s Rule: Government and Islam (New YorI: Columbia University Press,

2004), 177.

10

In Fa rabi `s cosmos, the First and the ten subsequent intelligibles (the last intelligible is the

Active Intellect aql Iaa ) are 'utterly incorporeal and are not in matter. While the celestial

bodies 'belong to the same genus as the material existents (oI the sublunary world), because they

have substrata, which resembles the matters which serve as the underlying carriers oI Iorms, and

things which are their Iorms as it were, by which they become substantiIied.Hence the Iorm oI

each oI these celestial bodies is actual` intellect, and the body thinIs by means oI this Iorm the

essence oI the separate` (immaterial) intellect Irom which it derives its existence, and it thinIs

the First. But because it also thinIs its substratum which is not intellect, that part oI its essence

which it thinIs is not entirely intellect, since it does not thinI with its substratum but only with

its Iorm. There is then in the celestial body an intelligible which is not intellectwhereas that

part oI its Iorm which it intelligizes is intellectit thus thinIs with an intellect which is not

identical with its entire substance. In this respect the celestial body diIIers Irom the First and

Irom the ten separate` intellects which are Iree Irom matter and any substratum, and has

something in common with man. Thus, Ior Fa rabi , the intelligible world would only include

those incorporeal or immaterial beings and thereIore would not include the celestial bodies,

which can be apprehended by the senses. Fa rabi discusses our mental apprehension oI the First

and so suggests that this world is perceived by our intellect alone. Fa rabi , Madi nah, 3.1-10, 7.3-

4; 1.11; tr. by Walzer 3.1-10, 7.3-4, 1.11. For the schematic oI Fa rabi `s cosmos, see Iootnote

264.

4

realm.

11

Charles Butterworth and Thomas Pangle maIe a thought-provoIing

assertion when they claim, 'To be sure, one learns to read AlIarabi with the

awareness that one is playing a game oI philosophic poIer with a benevolent

master teacher, who Ieeps hinting that you could win possession oI your own

soul Ior the Iirst time.

12

So, with this awareness in mind, it will be argued here

that happiness, i.e., ultimate happiness, is indeed the Iundamental theme in

Farabi`s philosophy in general and, in particular, in his Madinah.

Happiness, both in this liIe and in the aIterliIe, is intimately connected to

Farabi`s Virtuous City as only virtuous citizens can attain this happiness.

13

This

requires that we examine Farabi`s Virtuous City and in particular, its most

Iundamental and yet elusive detail: does it exist or has it ever existed? OI

course, there are arguments set Iorth by Richard Walzer and Majid FaIhry that

suggest that it has been established since Muhammad was indeed the Iounder oI

the Virtuous City.

14

Scholars such as Leo Strauss and his Iollowers insist that

the Virtuous City is an ideal, a city in speech, while others, such as Muhsin

11

Walzer wittily notes the diIIiculty with the parts oI Fa rabi `s cosmos that can be perceived only

with the intellect and that which can be perceived with our senses. He writes, 'Even in an

intellectual climate liIe that oI late pagan GreeI philosophywhich is saturated to such a large

extent with diIIicult abstract reasoningit needs some eIIort oI mind to convince oneselI oI the

existence oI an immaterial First Cause and oI ten invisible, spiritual, intellects on which the nine

celestial bodies with their special intellects and the changeable sublunary beings ultimately

depend. Hence we may turn with some relieI to the account oI the nine celestial spheres which

Iollows. The celestial bodies are not only visible and can thus be apprehended by our senses,

they diIIer Irom the First Cause and the ten subordinate immaterial intellects also in that they

move in space. Their circular movements are regular and can be described. Walzer, Virtuous

City, 375.

12

AlIarabi`s Philosophy oI Plato and Aristotle, translated by Muhsin Mahdi (Ithaca: Cornell

University Press, 2001), xiii.

13

In chapter sixteen oI Fa rabi `s Madi nah it is clearly demonstrated that only virtuous citizens

achieve happiness in the aIterliIe.

14

Walzer, Virtuous City, 16, 414, 441-442. See also Majid FaIhry, Al-Farabi, Founder oI Islamic

Neoplatonism: His LiIe, WorIs, and InIluence (OxIord: Oneworld, 2002), 103.

5

Mahdi suggest that it is a blueprint Ior Iounding such a city.

15

Some scholars

claim that Madinah reIlects the great schism Iound within Islam and that Farabi

is in Iact supporting Shi ism.

16

As we shall see, these assorted hypotheses

ignore what Farabi is conveying about happiness. Whatever the theories are

concerning Farabi`s Virtuous City, it has been noted that happiness, in this liIe

and in the next, is Ior the virtuous citizen alone. II the Virtuous City is only an

ideal, a theoretical city, then how does one become a citizen? This claim has

prompted some to suggest that only philosophers can achieve happiness since the

world is in essence comprised oI non-virtuous cities. And yet, iI Farabi`s

Virtuous City is to be realized, what does one do to become a citizen? II such a

city exists and iI it can be destroyed, how does one maintain his or her

citizenship in the Virtuous City? Finally, iI Farabi`s Madinah is merely

representative oI the problems oI his day, then what is the point oI his claim that

the virtuous citizen can and will attain happiness? These theories and others

leave the attainment oI happiness in a most tenuous position; thereIore, we need

to Iind a theory that allows the existence oI Farabi`s Virtuous City and

guarantees the attainment oI happiness Ior all oI its citizens.

II the highest state oI being that man can ultimately obtain lies in a realm

oI pure conceptual abstraction, as divorced Irom matter as it is possible to be, iI

15

Mahdi, AlIarabi: Political Philosophy, 6-7.

16

See Ola Abdelaziz Abouzeid, A Comparative Study between the Political Theories oI Al-

Fa ra bi and the Brethren oI Purity (Ph.D. Dissertation at University oI Toronto, 1987); W.

Montgomery Watt, Islamic Philosophy and Theology (Great Britain: Edinburgh University

Press, 1962), 54-56; M.G.S. Hodgson, The Venture oI Islam: Conscience and History in a World

Civilization, vol. I, The Classical Age oI Islam (Chicago: University oI Chicago Press, 1974),

433-436; F.M. Najja r, 'Fara bi `s Political Philosophy and Shi ism Studia Islamica XIV (1961):

57-72.

6

human perIection involves ascending towards the highest and purest level oI

thought, then can this imply that a Virtuous City, in which the sole aim oI its

citizens is Ielicity, will also lie on that rareIied conceptual plane? Farabi writes,

'Since we are mixed up with matter and since matter is the cause oI our

substances being remote Irom the First Substance, the nearer our substances

draw to it, the more exact and the truer will necessarily be our apprehension oI

it. Because the nearer we draw to separating ourselves Irom matter, the more

complete will be our apprehension oI the First Substance. We come nearer to it

only by becoming actual |or actually`| intellect. When we are completely

separated Irom matter, our mental apprehension oI the First will be at its most

perIect.

17

With this in mind, we shall argue that Farabi`s Virtuous City is not a

city oI words nor merely a utopian

18

Iantasy; it is not that heavenly city that

only philosophers discuss and can attain nor is it that perIect earthly city. It is

not a city that is to be established at all, Ior it already exists. Farabi`s Virtuous

City can be interpreted as a city that exists in the intelligible world or in the

incorporeal realm; indeed, it is an actual city; but not one that exists in the

material or corporeal world. We will demonstrate that Farabi`s Virtuous City is

comparable with Plotinus` |205-270 CE| third hypostasis,

19

i.e., the World Soul.

17

Farabi, Madi nah, 1.11; tr. Walzer, 1.11.

18

Utopia Irom the GreeI ou not and topos place. So utopia is literally no place, but it is

typically deIined as a real or imaginary society that is considered to be ideal. Traditionally

utopia is understood as a 'mode oI thought which deals solely with the temporal condition and

the nature oI utopia is that it promises through the establishment oI an ideal` state, the good

liIe` in this world. Dorothy F. Donnelly, 'Reconsidering the Ideal: The City oI God and

Utopian Speculation in The City oI God: a Collection oI Critical Essays edited with

introduction by Dorothy F. Donnelly (New YorI: Peter Lang Publishing, 1995), 206.

19

Hypostasis '(Irom Latin substance`) is 'the process oI regarding a concept or abstraction as

an independent or real entity. It is typically deIined as substance, essence, or underlying reality.

In Plotinus, the third hypostasis is part oI his chain oI being, via emanationism. Emanationism is

7

Focusing on the Plotinian inIluence in the thought oI Farabi does not entail

rejecting or negating the obvious and well-established Platonic and Aristotelian

inIluences. Nor am I reIuting any other inIluences that have been established by

Farabian scholarship. I simply want to examine a Plotinian line oI thought that

can be traced in Farabi`s worI.

20

The Virtuous City, liIe the Plotinian World

Soul, is where all perIected souls will go when they have no need oI a body, but

it is also where all souls reside beIore descending into the material world.

21

The

Virtuous City contains citizens that reside within the city and citizens that

reside in the material world. Through a comparison oI Farabi`s Virtuous City

with the Plotinian World Soul, we shall see that Farabi`s Virtuous City is not

unliIe Aurelius Augustine`s |354-430 CE| City oI God.

22

Augustine`s City oI

'a doctrine about the origin and ontological structure oI the world. |wherein| everything else

that exists is an emanation Irom a primordial unity, called by Plotinus the One.` The Iirst

product oI emanation Irom the One is Intelligence (no!s), a realm resembling Plato`s world oI

Forms. From Intelligence emanates Soul (psuche ), conceived as an active principle that imposes,

insoIar as that is possible, the rational structure oI Intelligence on the matter that emanates Irom

Soul. The process oI emanation is typically conceived to be necessary and timeless: although

Soul, Ior instance, proceeds Irom Intelligence, the notion oI procession is one oI logical

dependence rather than temporal sequence. The One remains unaIIected and undiminished by

emanation. In the thought oI Plotinus, the World Soul is the place where individual souls reside

beIore their descent into the material world and it is the place where souls strive to return. The

World Soul is the proper place Ior all souls and it is here that souls are happy because they have

union with the One; thus, ultimate happiness, Ior Plotinus, would be the return oI the individual

souls to the World Soul. Plotinus, Enn., IV.8.4-7; IV.3.12; V.1.4-6 Robert Audi, ed. The

Cambridge Dictionary oI Philosophy 2

nd

Ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999),

s.v. 'Hypostasis by C.F. Delaney; The Cambridge Dictionary oI Philosophy s.v. Emanationism

by William E. Mann.

20

For a brieI, but unique insight on the Plotinian inIluence in Islam, see Franz Rosenthal,

'Plotinus in Islam: The Power oI Anonymity in GreeI Philosophy in the Arab World: a

Collection oI Essays (Great Britain: Variorum Gower Pub., 1990), 437-446.

21

Plotinus, Enn., IV.8.4-7.

22

There is an ongoing debate about Augustine's use oI Plotinus. Many scholars argue that the

inIluence oI Plotinus is clear, while other scholars, who typically use Augustine`s Retractions as

a basis, deny all Plotinian inIluence. This paper will not examine these labyrinthine discussions;

it will simply examine a Iew concepts that can and have been perceived as Plotinian and compare

these concepts with another philosopher`s, i.e., Fa rabi `s, possible and similar use oI Plotinus. For

the heated debate concerning Augustine, see Gerard O'Daly, Platonism Pagan and Christian:

Studies in Plotinus and Augustine (Burlington: Ashgate Variorum, 2001). See also Augustine,

The Retractions trans. Sister Mary Inez Bogan (Washington: Catholic University Press, 1968).

8

God is a city that exists in the intelligible world; it has citizens both within the

city and here on earth.

23

We will also compare Farabi`s use oI Plotinus with that

oI Augustine, who provides an example oI another Iigure, within the conIines oI

a universal, monotheistic, and eschatological religion, who, liIe Farabi, utilized

GreeI philosophy to address the questions and problems oI his day.

24

In this

dissertation Augustine will be utilized solely as a case study. I will be relying

unreservedly on the scholarship that has thoroughly established the Plotinian

inIluence in Augustine`s thought.

25

By comparing the worIs oI Farabi with the worIs oI his predecessor

Plotinus, it may be possible to demonstrate by means oI textual analysis that

Farabi is discussing a city that exists in the intelligible world and that this city is

analogous to the Plotinian World Soul. A comparison oI the writings oI Farabi

and Plotinus, at least those Iound in the Theology oI Aristotle (or the Arabic

Plotinus), will demonstrate that though Farabi`s terminology diIIers Irom

Plotinus, the meaning is the same.

26

Scholars have long argued that Augustine

relied heavily on Plotinus in his quest to answer the questions oI how man has

Inowledge oI God and how he is to return to God. Thus, by comparing the texts

oI all three, it may be possible to illustrate how Farabi, liIe Augustine, utilized

23

The academic discussion oI whether Augustine`s City oI God is an earthly city or a city that

exists in the intelligible world will be addressed in chapter six, section I. Though this is an

ongoing debate, there is ample evidence to conclude that Augustine`s City oI God should not be

considered an earthly city. Obviously I am considering Augustine`s City oI God to be a city that

exists in the intelligible world.

24

This, oI course, is not the Iirst time that the thought oI Fa ra bi and Augustine have been

compared. See Ibrahim MadIour, 'La Place d`al Farabi dans l`Ecole Philosophique Musulmane

(Paris, 1934).

25

I do not claim to be an Augustinian scholar; thereIore, all arguments, concerning Augustine,

put Iorth in this dissertation are Iounded in secondary scholarship.

26

The Theology oI Aristotle and Fa rabi `s use oI this source will be discussed in some detail in

the next chapter.

9

the thought oI Plotinus in order to answer the ultimate questions: Why do men

desire happiness? How do they go about attaining it? And most importantly,

where can they attain this ultimate happiness? This dissertation sets out to

prove that happiness is the ultimate goal oI Farabi`s Madinah and Iurthermore,

that Farabi is in Iact telling his readers the paths to happiness and where this

happiness is to be attained. Farabi`s Virtuous City is where happiness in this

liIe, as well as ultimate happiness, is to be Iound; since only a citizen oI the

Virtuous City can be happy in this liIe and attain that ultimate happiness which

occurs when he returns to his proper place in the intelligible world, i.e., the

Virtuous City. How then shall we proceed to prove that Farabi`s Virtuous City

is indeed comparable to the Plotinian World Soul as the place where ultimate

happiness is attained? First, we shall looI at the concept oI happiness. Farabi,

liIe Plotinus and Augustine, was primarily concerned with the human desire Ior

happiness and he questioned how humans might have Inowledge oI this

happiness and how they were to attain it. Farabi, liIe Augustine, utilized the

Plotinian triple hypostasis |the One, Nous, and the World Soul| to reveal the

soul`s journey to the attainment oI happiness. Obviously, Farabi`s and

Augustine`s use oI Plotinus diIIers just as their circumstances diIIered, but their

goals, i.e., the means oI attaining happiness, are shared, and it is on this point

that their ideas may sustain a parallel. The notion oI happiness, as we shall see,

is not something that man learns or discovers; it is something that is already in

man Irom the outset. For Farabi, the Inowledge oI happiness is bestowed upon

10

man by an intelligible being, i.e., the Active Intellect

27

(aql Iaal), and the

attainment oI true or supreme happiness is ultimately achieved in the intelligible

world wherein the perIected soul will exist just beneath or within the Active

Intellect.

28

Augustine, in his search to understand how humans have Inowledge oI

happiness, considers Adam, the Iirst human. Augustine will essentially equate

Adam to the Plotinian World Soul because all men hence all souls come Irom

Adam, and Ior that reason, all men share in Adam`s Inowledge oI happiness.

UnliIe Plotinus and Farabi, Ior Augustine, the perIected souls will not return to

their source oI origin, instead they will ascend to a higher realm, i.e., the City oI

God. According to John Rist, Adam is most liIely the lower part oI the

Christianized Plotinian World Soul and the City oI God represents either the

upper level oI this World Soul or the Plotinian Nous.

29

ThereIore, we will argue

that both Farabi and Augustine conceive the soul`s journey as a descent Irom the

intelligible world into the material world and that they both posit the possibility

oI a return to the intelligible world. Farabi, liIe Plotinus and Augustine,

postulates a means to attain ultimate happiness. For Farabi both philosophy and

27

It is generally Inown that the concept oI the Active Intellect comes to us Irom Aristotle`s De

Anima III.5, but the term does not occur in the original GreeI, however it is mentioned three

times in the Arabic translation Arist utalis Ii `l-NaIs |etc.| . h aqqaqa-hu wa-qaddama la-hu

Abd al-Rah ma n Badawi (Dira sa t Isla miyya, 16), al-Qa hira, 1954, 75; See Walzer, Virtuous

City, 403.

28

Farabi, Madi nah, 13.5-6; tr. Walzer, 13.5-6. In Siyasah, there is a noted variant, wherein

perIected man achieves the ranI oI the Active Intellect, not the ranI beneath the Active Intellect.

Farabi, Kita b Al-Siya sa Al-Madaniyyah al-Mulaqqab bi-Maba di` al-Mawju da t (Principles oI

Beings or the Six Principles, or the Political Regime) edited with an introduction and notes by

Fauzi Najja r (Beirut: Catholic Press, 1964), 32.10; Fa rabi , Political Regime translated by

Therese-Anne Druart available through the Translation Clearing House (OIlahoma: OIlahoma

State University) Catalog reIerence number: A-30-50d., 32.10.

29

John Rist, Augustine: Ancient Thought Baptized (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

1994), 126, 128-129.

11

religion oIIer a means to happiness. Augustine, by contrast, claims Christian

Iaith alone as a means.

30

Both Farabi and Augustine contend that the perIected

soul, or the soul that has achieved ultimate happiness, will exist in the

intelligible world in a sort oI quasi-relationship with an intelligible being that in

many respects resembles the Plotinian Nous, thus connecting the individual soul

to the One or God.

Now, since ultimate happiness is an eternal happiness, it cannot be

realized in the sublunary world, which is in a constant state oI Ilux. That this

ultimate happiness is Iused with a city suggests that the Virtuous City and the

City oI God exist in the intelligible world. Surely, iI the highest Ielicity is to be

Iound in the realm oI pure abstract intellection, Ireed oI matter, then it maIes

sense that the city devoted to such Ielicity will also be located there. First, we

will examine the cosmos oI each oI the three writers. We will show how both

Farabi`s and Augustine`s cosmoi are similar and yet have marIed diIIerences

Irom Plotinus` emanation schematic; nevertheless, when we examine the City oI

God oI Augustine and the Virtuous City oI Farabi, we Iind that they are

analogous to the Plotinian World Soul. When we analyze Plotinus` World Soul,

we have, essentially, a description oI a perIect city. This city is based on a

rational hierarchy oI souls. II these individual souls remain in the World Soul,

they 'can share in its government, liIe those who live with a universal monarch

and share in the government oI his empire.

31

This city is the place oI every soul

30

But, as we shall see below Augustine considers anyone who is searching Ior truth to be a

citizen oI the City oI God. Thus he is allowing a path other than religion.

31

Plotinus, Enn., IV.8.4.

12

and it is only here that the individual soul can Iind eternal rest.

32

Augustine`s

City oI God, or the 'heaven oI the heaven, is described as that place where 'the

pure heart enjoys absolute concord and unity in the unshaIeable peace oI holy

spirits, the citizens oI your city in the heavens above the visible heavens.

33

Augustine`s City oI God clearly exists in the intelligible world; it exhibits a

complete harmony and permanence not Iound in the material world. The

individuals who reside in Augustine`s City oI God resemble the individual souls

within the Plotinian World Soul. There is a rational hierarchy Iound within the

City oI God and, as we shall see, it is in this city that Augustine`s criteria Ior

true happiness are met. Farabi`s Virtuous City is constructed in a way

comparable to the human soul and the healthy human body, but the salient point

is that it looIs and it Iunctions liIe the intelligible world. We Iind too that there

is the same rational hierarchy Iound within the Virtuous City as Iound in the

intelligible world and, oI course, as Iound within the Plotinian World Soul. In

Farabi`s Kita b al-Millah wa Nusus UIhra (BooI oI Religion), he compares the

Virtuous City and the natural or material world and there the Virtuous City

appears to be distinct Irom the material world. Farabi presents both the material

world and the Virtuous City as eternal entities. Furthermore, in his Madinah,

Farabi reveals that all men, whether they be virtuous, wicIed, or ignorant, were

at one point a part oI the Virtuous City. So it is reasonable to assert that Farabi

is claiming that all souls originate in the Virtuous City just as the World Soul is

32

Ibid., V.1.4.

33

Augustine, ConIessions, translated by Henry ChadwicI (New YorI: OxIord University Press,

1991), BI. XII. xi. 12

13

the point oI origin Ior all souls in the thought oI Plotinus. This implies that the

Virtuous City is an eternal city that exists in the intelligible world and that it is

comparable to Plotinus` World Soul. Farabi tells us that only virtuous citizens

will achieve eternal happiness, thus suggesting that not all souls will return to

the Virtuous City. This leaves us with unanswered questions: II all souls derive

Irom the Virtuous City, why do they not all return? What deIines a virtuous

citizen? How does one become a virtuous citizen? These are obviously questions

that must be answered in the material world, by us, Farabi`s readers. Clearly,

Farabi and Augustine are discussing two levels oI existence: the metaphysical

and the physical. We will maintain that the Virtuous City and the City oI God

are cities that exist in the intelligible world and that they are analogous to the

Plotinian World Soul, but in addition, we will show that the non-virtuous cities

and the City oI Man are essentially the cities that exist in the material world.

Farabi and Augustine classiIy a city, and implicitly its citizens, by their aims or

their loves. Augustine only examines two cities, the City oI God, whose love is

God, and the City oI Man, whose love is selI. Farabi examines various cities, but

in essence, considers only two cities: the Virtuous City, whose citizens aim Ior

happiness and thus live as the One intends, and the non-virtuous city, whose

citizens live Ior things other than true happiness and so, do not live as the One

intends. How then do we, who live in non-virtuous cities or in the City oI Man,

become citizens oI those cities oI the intelligible world and come to happiness?

For Plotinus, the World Soul is the 'homeland or 'Iatherland Ior all souls, but

when these individual souls exist in the material world, many no longer live in

14

accordance with the Nous and the One; hence, these souls become weaI and

isolated and Iorget their true home.

34

Even so, Plotinus maintains that by

contemplating what is above, i.e., the intelligible world, these individual souls

can Iind their way bacI; and ultimately achieve happiness.

35

Farabi`s Madinah,

liIe Augustine`s De Civitate Dei, clearly outlines a speciIic system oI Inowledge

and a speciIic way oI liIe; in this way, both Farabi and Augustine provide the

criteria to become virtuous citizens and citizens oI the City oI God. Plotinus`

concept oI the undescended soul, perhaps, provides another way oI looIing at

these virtuous citizens and citizens oI the City oI God, in that these citizens

become aware oI the higher part oI their soul and assimilate themselves to the

intelligible world. These citizens must live in the material world, but they too

can be citizens oI those cities that exist in the intelligible world. Farabi and

Augustine leave us with a choice to maIe: oI which city will we become

citizens?

34

Plotinus, Enn., IV.8.4.

35

Ibid.

15

Part One

Chapter One

Historiography

36

I. Historiography oI Arabic Philosophy.

Dimitri Gutas has recently provided a thorough account oI the problems

with the historiography oI Arabic philosophy.

37

Gutas visits some oI the

approaches and interpretations that are prevalent in the study oI Arabic

philosophy and reveals the negative consequences oI each. He begins with what

he calls the 'Orientalist approach and the antiquated Western view oI the

natives oI the Orient, which essentially describes Arabic philosophy as being

'mystical, sensual, otherworldly, non-rational and intensely interested in

religion..

38

Gutas insists that the perceptions stemming Irom the Orientalist

view maniIest itselI in various ways, e.g., that Arabic philosophy is nothing more

than 'mystical, only an intermediary between GreeI and medieval Latin

philosophy, as being concerned only about the relationship between religion and

philosophy, and as coming to an end with Averroes, when the torch was passed

on to the West.

39

Next, he discusses the 'Illuminationist approach, in which

he Iocuses primarily on Henry Corbin. Gutas asserts that Corbin`s methodology,

which he claims is an oIIshoot oI the Orientalist approach, maIes Arabic

36

This historiography will Iocus mainly on al-Fara bi since he is the subject oI this dissertation.

37

Dimitri Gutas, 'The Study oI Arabic Philosophy in the Twentieth Century: an Essay on the

Historiography oI Arabic Philosophy in British journal oI Middle Eastern Studies (2002) 29 (1),

5-25.

38

Ibid., 8. Gutas notes that the term 'Orientalist is a 'loaded term, but claims that it is

necessary to reIer to it because it provides a IrameworI oI the nineteenth century view oI the

natives oI the Orient and he claims this picture, although it is a caricature, determined the types

oI questions that were asIed by scholars. Gutas also notes Mahdi`s worI that emphasizes the

pervasiveness oI these notions. See Muhsin Mahdi, 'Orientalism and the Study oI Islamic

Philosophy, in Journal oI Islamic Studies, 1 (1990), 79-93. Gutas, 'Historiography,8.

39

Ibid.

16

philosophy nothing more than a Iusion oI mysticism and theology.

40

Finally,

Gutas examines the 'Political approach, which will be discussed in depth, since

it invariably Iocuses on Farabi.

First, it is necessary to examine Gutas` classiIications as they concern

Farabi. So we shall begin with the standard claim that Arabic philosophers were

attempting the harmonization oI philosophy and religion, a claim that is

commonly made about Farabi`s writings.

41

Gutas asserts that Oliver Leaman is

'most obviously guilty oI this misconception, but in truth this assertion is so

ensconced within the reading material that it is generally accepted as common

Inowledge.

42

Gutas claims that Leaman`s worI would have us believe that

'medieval Arabic philosophy was in Iact nothing else but a continuous squabble

through and across the centuries about the relative truth values oI religion and

philosophy.

43

Obviously Gutas disagrees with the claim that the Arabic

philosophers` salient Iocus was the harmonization oI philosophy and religion.

40

Ibid., 18.

41

As noted above, Gutas insists that this claim stems Irom the Orientalist approach.

42

Gutas, 'Historiography, 12. This is a common interpretation oI Fa ra bi `s texts. See Oliver

Leaman An Introduction to Medieval Islamic Philosophy (New YorI: Cambridge University

Press, 1985); Oliver Leaman, 'Does the Interpretation oI Islamic Philosophy Rest on a MistaIe,

in International Journal oI Middle East Studies vol. 12 no.4 (Dec. 1980), 525-538;Mahdi,

AlIarabi: Political Philosophy , 3; Mahdi, 'Al-Farabi in History oI Political Philosophy, 3

rd

edition. Edited by Leo Strauss and Joseph Cropsey (Chicago: University oI Chicago Press,

1987), 206; Medieval Political Philosophy: a SourcebooI edited by Ralph Lerner and Muhsin

Mahdi with the collaboration oI Ernest L. Fortin (Canada: The Free Press oI Glencoe Collier-

Macmillan Limited, 1963), 1.

43

Gutas, 'Historiography, 12-13. In his examination oI Leaman`s An Introduction to Medieval

Islamic Philosophy, Gutas argues that the purpose oI this booI as Leaman states in his PreIace, is

'to discuss some oI the leading themes oI Islamic philosophy by analyzing the arguments oI

some oI the most important philosophers concerned, and by relating those arguments to GreeI

philosophy on the one hand and to the principles oI religion on the other` (p. xii, emphasis

added). II this is the purpose oI the booI, then it cannot be an introduction to medieval Islamic

philosophy, unless one holds that its leading theme and major achievement were the discussion oI

the respective merits oI religion and philosophy. Gutas, review oI 'An Introduction to

Medieval Islamic Philosophy, by Oliver Leaman, in Islam 65 (1988): 340.

17

Gutas argues that the philosophers were interested in philosophy, and only

philosophy.

A.! Gutas` Critique oI Strauss.

The notion oI the harmonization oI philosophy and religion is, according

to Gutas, an important aspect oI Leo Strauss`s and his Iollowers` interpretation

oI Arabic philosophy. Gutas places their interpretation under the 'Political

approach. Gutas writes:

Strauss`s interpretation oI Arabic philosophy is based on two

assumptions: Iirst, it is assumed that philosophers writing in Arabic

worIed in a hostile environment and were obliged to represent their

views as being in conIormity with Islamic religion; and second, that they

had to present their real philosophical views in disguise. What is required

|thereIore, in order to understand their text,| is a Iey to understanding the

peculiar way in which the text has been composed, and that Iey is to be

Iound by paying attention to the conIlict between religion and

philosophy.`

44

Gutas disagrees that there was a hostile environment Ior those philosophers

writing in Arabic and he questions why the Straussians do not bother to cite

evidence iI such an environment existed.

45

He examines Charles Butterworth`s

claim that 'Islamic political philosophy has always been pursued in a setting

44

Gutas, 'Historiography, 20; Leaman, 'Does the Interpretation oI Islamic Philosophy Rest on a

MistaIe, 525.

45

Gutas cites examples oI the so-called persecutions. He claims:

Suhrawardi (d. 1192), who is usually cited as an example in this connection (most

recently by GriIIel, Apostasie, p.358) was executed because he had usurped, though an

outsider to Aleppo, the position oI the local ulama ` as conIidant and manipulator oI the

prince, al-MaliI al-Z a hir, Saladin`s son. The execution oI Abu l-Maa li al-Maya nji (d.

1131; also cited by GriIIel) tooI place not because oI his philosophical belieIs but, as

even al-Bayhaqi reports, on account oI an enmity between him and the vizier Abu` l-

Qsim al-Anasa ba dhi `, see M. MeyeroI, `Ali al-Bayaqi `s Tatimmat S iwa n al-HiIma`,

Osiris 8 (1948), p. 175.

Gutas claims that the so-called persecutions are incorrect even in the case oI Maimonides. Gutas

states that 'he |Maimonides| and his Iamily were persecuted by the Almohads and had to leave

Spain in 1149 not because Moses was a philosopherin any case, he was barely in his teens at

the timebut because they were Jews. Gutas, 'Historiography, 20.

18

where great care had to be taIen to avoid violating the revelations and traditions

accepted by the Islamic community..`

46

Gutas claims that these types oI

statements are continually given as hard Iacts and yet there is no evidence given

to support them.

47

Even Miriam Galston, a Iellow Straussian, questions the

degree oI the threatening religious climate as understood by Strauss. She insists

that 'there is no prima Iacie reason to assume a completely hostile relationship

between AlIarabi (and those similarly situated) and the religious establishment

at that time.

48

Indeed, Gutas insists that 'were one, however, truly to

investigate Arabic philosophy dispassionately and objectively, it would be

immediately clear to him that religion versus philosophy is but a minor subject

oI concern, and only at certain times and in certain places. Islamic Spain at the

time oI Averroes may have been such a place, but this is very Iar Irom

characterizing the entire Islamic world during the 10 centuries oI Arabic

philosophy that I talIed about at the outset.

49

The second assumption oI Strauss` interpretation, which is the

philosopher`s deliberate disguise oI his true philosophy, essentially rests on the

Iirst assumption, which is tenuous at best. Nevertheless, Gutas argues: 'II one

assumes a philosopher not to have meant what he said and always to have