Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Muhammad Yasir

Muhammad Yasir

Uploaded by

Qamar ZiaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- BIGO LIVE Broadcaster AgreementDocument5 pagesBIGO LIVE Broadcaster Agreements zamanNo ratings yet

- Socio Economic Indicators and Democratic Consolidation in Pakistan An AnalysisDocument15 pagesSocio Economic Indicators and Democratic Consolidation in Pakistan An AnalysisOsama AsgharNo ratings yet

- Demography Changes Implications For India and World Combined Papers 1Document174 pagesDemography Changes Implications For India and World Combined Papers 1Parveen KumarNo ratings yet

- AnUncertainGlory IndiaanditsContradictionsDocument6 pagesAnUncertainGlory IndiaanditsContradictionsSandeep SoniNo ratings yet

- Determining The Strength of Argument: Submitted By: Arbaz Iftikhar Roll No: 1201-BH-PS-17 Section: A-2Document12 pagesDetermining The Strength of Argument: Submitted By: Arbaz Iftikhar Roll No: 1201-BH-PS-17 Section: A-2Arbaz iftikharNo ratings yet

- Vikas Ranjan Essay Test 1Document22 pagesVikas Ranjan Essay Test 1ShubhadityaChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- The Dynamic Relationship Between Democracy and Education in PakistanDocument15 pagesThe Dynamic Relationship Between Democracy and Education in PakistanBasheer AhmedNo ratings yet

- Education Impacts All Facets of National DevelopmentDocument2 pagesEducation Impacts All Facets of National DevelopmentGirijesh PandeyNo ratings yet

- Inequalityis The Difference in Social Status, Wealth, or Opportunity Between People or Groups. Inequality Can BeDocument9 pagesInequalityis The Difference in Social Status, Wealth, or Opportunity Between People or Groups. Inequality Can BeSweta RajputNo ratings yet

- Free Exchange Democracy GrowthDocument3 pagesFree Exchange Democracy GrowthKendallLamaestraNo ratings yet

- Unit 11 Demographic DividendDocument11 pagesUnit 11 Demographic DividendRiddhi MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Democracy Well Researched Articles.Document52 pagesDemocracy Well Researched Articles.Junaid SaqibNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Indian Economy Since Independence: Persisting Colonial DisruptionDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: Indian Economy Since Independence: Persisting Colonial DisruptiontonyvinayakNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Welfare in Indonesia's Reform Era: Iing Nurdin, Mohd Rizal Mohd YakoopDocument14 pagesDemocracy and Welfare in Indonesia's Reform Era: Iing Nurdin, Mohd Rizal Mohd YakoopindraNo ratings yet

- Democracy ArticlesDocument53 pagesDemocracy Articleskg243173No ratings yet

- Population Growth: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument4 pagesPopulation Growth: Challenges and OpportunitiesattiqNo ratings yet

- Bureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in IndiaDocument25 pagesBureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in Indiachandan8181No ratings yet

- Paper - Terrorism and Demo Divident - PakDocument24 pagesPaper - Terrorism and Demo Divident - PakAnirban DeNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Gender Inequality in PakistanDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Gender Inequality in Pakistanaflbsjnbb100% (1)

- Written By: Bima Fatwa Muharram 5015201148Document6 pagesWritten By: Bima Fatwa Muharram 5015201148Sir AlexNo ratings yet

- Surinder S. Jodhka and Jules Naudet - Mapping The Elite - Power, Privilege, and Inequality-OUP (1) - 1-44Document44 pagesSurinder S. Jodhka and Jules Naudet - Mapping The Elite - Power, Privilege, and Inequality-OUP (1) - 1-44preenasoam94No ratings yet

- Defining India's Middle ClassDocument2 pagesDefining India's Middle ClassSam T MathewNo ratings yet

- CorruptionDocument13 pagesCorruptionMoiz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Nigeria's Security Challenges and The Crisis of DevelopmentDocument10 pagesNigeria's Security Challenges and The Crisis of DevelopmentAliyu Mukhtar Katsina, PhD100% (3)

- Good Governance CompleteDocument19 pagesGood Governance CompleteKaleem MarwatNo ratings yet

- Practical Politics Being Notorious in PakDocument8 pagesPractical Politics Being Notorious in Pakstfu.dNo ratings yet

- Education Is Not A Tool To Change The World - It Is A Weapon Employed To Ensure It Stays The Same.Document3 pagesEducation Is Not A Tool To Change The World - It Is A Weapon Employed To Ensure It Stays The Same.Justt MeeNo ratings yet

- Fifty Years of Bangladesh: Achievement in Population SectorDocument6 pagesFifty Years of Bangladesh: Achievement in Population SectorInternational Journal of Business Marketing and ManagementNo ratings yet

- 8.1 Youth Bulge and Their Role in DemocracyDocument5 pages8.1 Youth Bulge and Their Role in DemocracyArbaz KhanNo ratings yet

- FACTORS ON DEMOCRACY IN MALAYSIA - LyaneDocument2 pagesFACTORS ON DEMOCRACY IN MALAYSIA - LyaneLYANE SANGGAE LESLEYNo ratings yet

- Population Policy PakistanDocument26 pagesPopulation Policy PakistanMuhammad AlamNo ratings yet

- Culture and Pol-WPS OfficeDocument8 pagesCulture and Pol-WPS OfficeSamood JanNo ratings yet

- Demographic Dividend For Ep WDocument23 pagesDemographic Dividend For Ep WBhavishya Kumar KaimNo ratings yet

- Summary of Chapters 8 and 9Document4 pagesSummary of Chapters 8 and 9kawazaki narotoNo ratings yet

- Agmented MediaDocument3 pagesAgmented MediaKashif KhuhroNo ratings yet

- Pak Study .,LMDocument13 pagesPak Study .,LMabdul mannanNo ratings yet

- Extremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieDocument9 pagesExtremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieM ZainNo ratings yet

- Women's Impact On Indian DevelopmentDocument31 pagesWomen's Impact On Indian DevelopmentrheaNo ratings yet

- Humanism Moreblessing - 2Document5 pagesHumanism Moreblessing - 2munaxemimosa8No ratings yet

- Electronic Media in Pakistan - by Azam Khan: E-Books General Politics Comment!Document19 pagesElectronic Media in Pakistan - by Azam Khan: E-Books General Politics Comment!Usman MumtazNo ratings yet

- India: The Next Superpower?: Globalisation, Society and InequalitiesDocument7 pagesIndia: The Next Superpower?: Globalisation, Society and InequalitiesMuhammad ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Globalisation, Society and Inequalities: Harish WankhedeDocument6 pagesGlobalisation, Society and Inequalities: Harish WankhedesofiagvNo ratings yet

- Review Related Literature Population GrowthDocument8 pagesReview Related Literature Population Growthaflspwxdf100% (1)

- Good Governance in Pakistan Problems and Proposed SolutionDocument20 pagesGood Governance in Pakistan Problems and Proposed SolutionAzeem ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Human Development in IndiaDocument9 pagesResearch Paper On Human Development in Indiarcjbhsznd100% (1)

- The State of Democratic Governance in IndiaDocument27 pagesThe State of Democratic Governance in IndiaJakish DixitNo ratings yet

- Ayesha Khurshid: Summary of The Article "Document2 pagesAyesha Khurshid: Summary of The Article "Ishfaq AhmedNo ratings yet

- Socio Economic Problems of PakistanDocument12 pagesSocio Economic Problems of PakistanSyed Mustafa NajeebNo ratings yet

- Assignment 4 (Ali Hassan)Document4 pagesAssignment 4 (Ali Hassan)ali hassanNo ratings yet

- Caste in The NewsroomDocument13 pagesCaste in The NewsroomishicaaNo ratings yet

- FullReport Project2045Document201 pagesFullReport Project2045Fresy NugrohoNo ratings yet

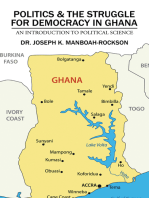

- Politics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceFrom EverandPolitics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceNo ratings yet

- Rsis Commentaries: Indonesia's Rising Middle Class: Tweeting To Be HeardDocument2 pagesRsis Commentaries: Indonesia's Rising Middle Class: Tweeting To Be HeardudelkingkongNo ratings yet

- Article of Global Society & IndonesiaDocument12 pagesArticle of Global Society & IndonesiaHendra Manurung, S.IP, M.ANo ratings yet

- Christie IlliberalDemocracyModernisation 1998Document18 pagesChristie IlliberalDemocracyModernisation 1998alicorpanaoNo ratings yet

- The Requirements of Social JusticeDocument3 pagesThe Requirements of Social JusticeAung Kyaw MoeNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper 2, HeñorgaDocument2 pagesReflection Paper 2, HeñorgaVince HeñorgaNo ratings yet

- MENINGITIS Lesson PlanDocument12 pagesMENINGITIS Lesson PlannidhiNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship 2019: Reculta Solutions, GurgaonDocument6 pagesSummer Internship 2019: Reculta Solutions, GurgaonAbhishek KujurNo ratings yet

- BangladeshDocument6 pagesBangladeshKhalid AhmedNo ratings yet

- Direct XCD PDFDocument12 pagesDirect XCD PDFjhuggghNo ratings yet

- 2023 01 Ansys General Hardware RecommendationsDocument22 pages2023 01 Ansys General Hardware RecommendationsShravani ZadeNo ratings yet

- CH. 1 SignalsDocument29 pagesCH. 1 SignalsSohini ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Foundation Lecture (Abdulhafiz)Document4 pagesFoundation Lecture (Abdulhafiz)desigandNo ratings yet

- EC287 - Presentation To Community Board 4-RRA 03032022Document12 pagesEC287 - Presentation To Community Board 4-RRA 03032022Christina WilkinsonNo ratings yet

- Patnership NotesDocument3 pagesPatnership NotesMario Jr ShetyNo ratings yet

- Disjuntor SF1 - Dados ElétricosDocument1 pageDisjuntor SF1 - Dados ElétricosotavioalcaldeNo ratings yet

- Sniffer Nano ManualDocument5 pagesSniffer Nano ManualMuhammad SalmanNo ratings yet

- Dealscope Google Fitbit PDFDocument1 pageDealscope Google Fitbit PDFPrasnth KumarNo ratings yet

- Notes MT Module I - KTUDocument47 pagesNotes MT Module I - KTURagesh Dudu100% (1)

- TC15M 65M Manual PDFDocument15 pagesTC15M 65M Manual PDFReciclando ChatarraNo ratings yet

- OTC107207 OptiX NG WDM Optical Layer Data Configuration ISSUE 1Document28 pagesOTC107207 OptiX NG WDM Optical Layer Data Configuration ISSUE 1ARMAND NGUETSA SONKENGNo ratings yet

- Alexander Gelman: Born: 1967 Education: Moscow Art Institute Currently Resides: New York City Selected Honors: AwardsDocument5 pagesAlexander Gelman: Born: 1967 Education: Moscow Art Institute Currently Resides: New York City Selected Honors: AwardsLaHipiNo ratings yet

- Dishwasher 2011Document20 pagesDishwasher 2011chamaljsNo ratings yet

- 2012jal PDFDocument239 pages2012jal PDFAfifah WijayaNo ratings yet

- Task 4Document6 pagesTask 4paul.rieger.1No ratings yet

- Pemberton Asian Opportunities Fund Emerges As Substantial Shareholder of SGX-Listed JukenDocument2 pagesPemberton Asian Opportunities Fund Emerges As Substantial Shareholder of SGX-Listed JukenWeR1 Consultants Pte LtdNo ratings yet

- Toll ManagementDocument44 pagesToll ManagementJay PatelNo ratings yet

- Flame Detector SiemensDocument4 pagesFlame Detector SiemensErvin BošnjakNo ratings yet

- Akira TVDocument22 pagesAkira TVErmand WindNo ratings yet

- ORLANDI Catalogue Blue en-DEDocument44 pagesORLANDI Catalogue Blue en-DEtinashemambarizaNo ratings yet

- Variable Pitch Fan System - If EquippedDocument3 pagesVariable Pitch Fan System - If EquippedEVER DAVID SAAVEDRA HUAYHUANo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Basic Concepts and Computer EvolutionDocument23 pagesChapter 1 - Basic Concepts and Computer EvolutionM KalaounNo ratings yet

- Digital Communications: Design For The Real WorldDocument19 pagesDigital Communications: Design For The Real WorldShunyi LiuNo ratings yet

- V.1 Comment Opposiiton To Defendant's Motion For Extension of Time To File AnswerDocument2 pagesV.1 Comment Opposiiton To Defendant's Motion For Extension of Time To File AnswerRhows Buergo100% (1)

- Precedents For The Reply of The Coca COla CompanyDocument3 pagesPrecedents For The Reply of The Coca COla CompanyLex OraculiNo ratings yet

Muhammad Yasir

Muhammad Yasir

Uploaded by

Qamar ZiaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Muhammad Yasir

Muhammad Yasir

Uploaded by

Qamar ZiaCopyright:

Available Formats

Muhammad Yasir

5:51pm Sep 6

Education Development It is no exaggeration to say that education and human development are interlinked and complementary and it is a fundamental point that evaluates the nations real worth. The quality of the people is the quality of nation, the development of one is to develop the nation. Development is the expansion of choices, so how can choices be made more meaningful and effective? Awareness of the consequences made the choices effective, and all this can be achieved through education. That is the only way through which people can gain the opportunity and direct their development. Social actors at all levels must understand the fact that true development is impossible with out challenging and improving the quality of mindsets. An analysis on the progress of human development has been done, which indicates that human development is interlinked with education. Another study has been done on 83 developing countries, which indicates that 12 developing countries with fastest growth rate also had a well above average level of literacy. An increase in the literacy rate from 20 to 30 per cent is associated with a national income increase of 8 to 16 per cent. Education plays a vital role in socioeconomic factor, which ultimately form basis for democracy. Economic development improves health and societal well being. Thus education can significantly influence democracy and the development of civil society. Education participates in political processes and promotes democratic practices of multicultural and pluralism. According to World Bank, between 60 to 90 percent growth achieved by Japan and other East Asian industrialized countries is through by human capital rather by financial means or natural resources. This study also depicts that farmers and laboures with better education adjust more rapidly to technological and societal changes, which ultimately and more likely to increase their productivity at individual level, communal and nation levels. Education is an important source of empowering individuals with self awareness and confidence needed for meaningful critical discussions. It is estimated that one additional year of education can increase productivity in wage employment by 10 per cent. Seven countries ranking highest in human development associate their achievement with their commitment to health and education. Pakistan is on 125 out of 169 nations of united nation report on human development published in 2010. At the beginning 21st century only one in two children aged five to nine attends schools in Pakistan; and perhaps as many as half of primary school graduates are functionally illiterate. This gigantic task of education cannot be undertaken in isolation, it demands partnership between public and private actors. A paradigm shift in policies and priorities is required in education that accelerates the growth rate of human development. No doubt a tremendous amount of commitment is required to equalize opportunities through the creation of laws, polices and procedures that create an environment for meaningful participation at all levels. But with out education, achieving sustainable human development will remain an illusion.

This Op-Ed piece makes no claim to originality; it is a rough transcript of thoughts that flitted across the writers mind while reading a recent article in The Economist published under the title The new middle classes rise up. Citing India, China, Indonesia and Brazil as examples, the article points out that these emerging markets are experiencing the early stirrings of political demands by the growing ranks of their middle classes. India gets highlighted by the urban support Anna Hazare got for his anti-corruption crusade and China by the extensive internal criticism triggered off by the rail crash involving two high-speed trains and by demonstrations in the town of Dalian following damage to a chemical factory; protesters attributed both the incidents to corruption and official neglect. The Chinese middle class is estimated at 800 million and the Indian at 300 million with calculations based on people earning between $2-$13 a day. By the same token Pakistans middle class is 120 million strong but this engaging article makes no reference to it perhaps because Pakistans economic performance over several years has been too dismal to merit description as an emerging market and also because of the perception that its middle class is too inert to be an agent of change. Many economists have differed from the World Bank criteria and argued that in countries set on a course of economic liberalisation, growth entry to the middle class should be pegged at people earning a minimum of $10 a day. According to some studies there were 30 to 35 million Pakistanis earning an average of $10,000 a year and of these, about 17 million are in the upper middle class. Pakistans middle class should, therefore, have a more solid base than that of India. Amongst other

indices is the rapid growth of phones, internet usage and access to radio and television. Its inertia needs a different explanation. The much admired Amartya Sen claims an ancient tradition of public reasoning and argumentative heterodoxy for India that was practised both by Ashoka and Akbar. The Indian middle class resorting to action, therefore, has a hallowed provenance. Interestingly, Sen illustrates his point by recalling Arrians account of Jain philosophers admonishment to Alexander the Great during his stay in what is now Pakistan. One possible difference between the two post-1947 neighbours is that while the Indian middle class already feels empowered enough to assert a change, its Pakistani counterpart is as yet unable to convert thought into action. Pakistanis are otherwise no less argumentative (Sen) than the Indians. In fact, the passions that welled up in Pakistan when General Musharraf stretched his tyranny to the higher judiciary suggested that its middle class was more combative than that of India. The momentum influenced the general election and opened a great vista of parliamentary democracy. But a lethal combination of President Zardaris preference for ruling through cabals, substitution of economic policy by plunder and day to day interference by the two Anglo-Saxon powers subverted the democratic process. Unable to influence decision-making and confronted with 26% inflation rate, the middle class saw its lower echelons slide down the bar. It crawled back into drawing rooms to chatter and seek catharsis in inane TV talk shows. As more than one political party came under mafia style management there was regression into tribalism, sectarian tensions and linguistic and ethnic conflicts. Politically speaking, Pakistans middle class is a work in progress. It will find no messiah but the option to regenerate itself through mass action with its inherent collective dynamics still exists and awaits a catalyst.

You might also like

- BIGO LIVE Broadcaster AgreementDocument5 pagesBIGO LIVE Broadcaster Agreements zamanNo ratings yet

- Socio Economic Indicators and Democratic Consolidation in Pakistan An AnalysisDocument15 pagesSocio Economic Indicators and Democratic Consolidation in Pakistan An AnalysisOsama AsgharNo ratings yet

- Demography Changes Implications For India and World Combined Papers 1Document174 pagesDemography Changes Implications For India and World Combined Papers 1Parveen KumarNo ratings yet

- AnUncertainGlory IndiaanditsContradictionsDocument6 pagesAnUncertainGlory IndiaanditsContradictionsSandeep SoniNo ratings yet

- Determining The Strength of Argument: Submitted By: Arbaz Iftikhar Roll No: 1201-BH-PS-17 Section: A-2Document12 pagesDetermining The Strength of Argument: Submitted By: Arbaz Iftikhar Roll No: 1201-BH-PS-17 Section: A-2Arbaz iftikharNo ratings yet

- Vikas Ranjan Essay Test 1Document22 pagesVikas Ranjan Essay Test 1ShubhadityaChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- The Dynamic Relationship Between Democracy and Education in PakistanDocument15 pagesThe Dynamic Relationship Between Democracy and Education in PakistanBasheer AhmedNo ratings yet

- Education Impacts All Facets of National DevelopmentDocument2 pagesEducation Impacts All Facets of National DevelopmentGirijesh PandeyNo ratings yet

- Inequalityis The Difference in Social Status, Wealth, or Opportunity Between People or Groups. Inequality Can BeDocument9 pagesInequalityis The Difference in Social Status, Wealth, or Opportunity Between People or Groups. Inequality Can BeSweta RajputNo ratings yet

- Free Exchange Democracy GrowthDocument3 pagesFree Exchange Democracy GrowthKendallLamaestraNo ratings yet

- Unit 11 Demographic DividendDocument11 pagesUnit 11 Demographic DividendRiddhi MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- Democracy Well Researched Articles.Document52 pagesDemocracy Well Researched Articles.Junaid SaqibNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Indian Economy Since Independence: Persisting Colonial DisruptionDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: Indian Economy Since Independence: Persisting Colonial DisruptiontonyvinayakNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Welfare in Indonesia's Reform Era: Iing Nurdin, Mohd Rizal Mohd YakoopDocument14 pagesDemocracy and Welfare in Indonesia's Reform Era: Iing Nurdin, Mohd Rizal Mohd YakoopindraNo ratings yet

- Democracy ArticlesDocument53 pagesDemocracy Articleskg243173No ratings yet

- Population Growth: Challenges and OpportunitiesDocument4 pagesPopulation Growth: Challenges and OpportunitiesattiqNo ratings yet

- Bureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in IndiaDocument25 pagesBureaucracy-A Hindrance To Growth in Indiachandan8181No ratings yet

- Paper - Terrorism and Demo Divident - PakDocument24 pagesPaper - Terrorism and Demo Divident - PakAnirban DeNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Gender Inequality in PakistanDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Gender Inequality in Pakistanaflbsjnbb100% (1)

- Written By: Bima Fatwa Muharram 5015201148Document6 pagesWritten By: Bima Fatwa Muharram 5015201148Sir AlexNo ratings yet

- Surinder S. Jodhka and Jules Naudet - Mapping The Elite - Power, Privilege, and Inequality-OUP (1) - 1-44Document44 pagesSurinder S. Jodhka and Jules Naudet - Mapping The Elite - Power, Privilege, and Inequality-OUP (1) - 1-44preenasoam94No ratings yet

- Defining India's Middle ClassDocument2 pagesDefining India's Middle ClassSam T MathewNo ratings yet

- CorruptionDocument13 pagesCorruptionMoiz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Nigeria's Security Challenges and The Crisis of DevelopmentDocument10 pagesNigeria's Security Challenges and The Crisis of DevelopmentAliyu Mukhtar Katsina, PhD100% (3)

- Good Governance CompleteDocument19 pagesGood Governance CompleteKaleem MarwatNo ratings yet

- Practical Politics Being Notorious in PakDocument8 pagesPractical Politics Being Notorious in Pakstfu.dNo ratings yet

- Education Is Not A Tool To Change The World - It Is A Weapon Employed To Ensure It Stays The Same.Document3 pagesEducation Is Not A Tool To Change The World - It Is A Weapon Employed To Ensure It Stays The Same.Justt MeeNo ratings yet

- Fifty Years of Bangladesh: Achievement in Population SectorDocument6 pagesFifty Years of Bangladesh: Achievement in Population SectorInternational Journal of Business Marketing and ManagementNo ratings yet

- 8.1 Youth Bulge and Their Role in DemocracyDocument5 pages8.1 Youth Bulge and Their Role in DemocracyArbaz KhanNo ratings yet

- FACTORS ON DEMOCRACY IN MALAYSIA - LyaneDocument2 pagesFACTORS ON DEMOCRACY IN MALAYSIA - LyaneLYANE SANGGAE LESLEYNo ratings yet

- Population Policy PakistanDocument26 pagesPopulation Policy PakistanMuhammad AlamNo ratings yet

- Culture and Pol-WPS OfficeDocument8 pagesCulture and Pol-WPS OfficeSamood JanNo ratings yet

- Demographic Dividend For Ep WDocument23 pagesDemographic Dividend For Ep WBhavishya Kumar KaimNo ratings yet

- Summary of Chapters 8 and 9Document4 pagesSummary of Chapters 8 and 9kawazaki narotoNo ratings yet

- Agmented MediaDocument3 pagesAgmented MediaKashif KhuhroNo ratings yet

- Pak Study .,LMDocument13 pagesPak Study .,LMabdul mannanNo ratings yet

- Extremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieDocument9 pagesExtremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieM ZainNo ratings yet

- Women's Impact On Indian DevelopmentDocument31 pagesWomen's Impact On Indian DevelopmentrheaNo ratings yet

- Humanism Moreblessing - 2Document5 pagesHumanism Moreblessing - 2munaxemimosa8No ratings yet

- Electronic Media in Pakistan - by Azam Khan: E-Books General Politics Comment!Document19 pagesElectronic Media in Pakistan - by Azam Khan: E-Books General Politics Comment!Usman MumtazNo ratings yet

- India: The Next Superpower?: Globalisation, Society and InequalitiesDocument7 pagesIndia: The Next Superpower?: Globalisation, Society and InequalitiesMuhammad ibrahimNo ratings yet

- Globalisation, Society and Inequalities: Harish WankhedeDocument6 pagesGlobalisation, Society and Inequalities: Harish WankhedesofiagvNo ratings yet

- Review Related Literature Population GrowthDocument8 pagesReview Related Literature Population Growthaflspwxdf100% (1)

- Good Governance in Pakistan Problems and Proposed SolutionDocument20 pagesGood Governance in Pakistan Problems and Proposed SolutionAzeem ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Human Development in IndiaDocument9 pagesResearch Paper On Human Development in Indiarcjbhsznd100% (1)

- The State of Democratic Governance in IndiaDocument27 pagesThe State of Democratic Governance in IndiaJakish DixitNo ratings yet

- Ayesha Khurshid: Summary of The Article "Document2 pagesAyesha Khurshid: Summary of The Article "Ishfaq AhmedNo ratings yet

- Socio Economic Problems of PakistanDocument12 pagesSocio Economic Problems of PakistanSyed Mustafa NajeebNo ratings yet

- Assignment 4 (Ali Hassan)Document4 pagesAssignment 4 (Ali Hassan)ali hassanNo ratings yet

- Caste in The NewsroomDocument13 pagesCaste in The NewsroomishicaaNo ratings yet

- FullReport Project2045Document201 pagesFullReport Project2045Fresy NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Politics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceFrom EverandPolitics & the Struggle for Democracy in Ghana: An Introduction to Political ScienceNo ratings yet

- Rsis Commentaries: Indonesia's Rising Middle Class: Tweeting To Be HeardDocument2 pagesRsis Commentaries: Indonesia's Rising Middle Class: Tweeting To Be HeardudelkingkongNo ratings yet

- Article of Global Society & IndonesiaDocument12 pagesArticle of Global Society & IndonesiaHendra Manurung, S.IP, M.ANo ratings yet

- Christie IlliberalDemocracyModernisation 1998Document18 pagesChristie IlliberalDemocracyModernisation 1998alicorpanaoNo ratings yet

- The Requirements of Social JusticeDocument3 pagesThe Requirements of Social JusticeAung Kyaw MoeNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper 2, HeñorgaDocument2 pagesReflection Paper 2, HeñorgaVince HeñorgaNo ratings yet

- MENINGITIS Lesson PlanDocument12 pagesMENINGITIS Lesson PlannidhiNo ratings yet

- Summer Internship 2019: Reculta Solutions, GurgaonDocument6 pagesSummer Internship 2019: Reculta Solutions, GurgaonAbhishek KujurNo ratings yet

- BangladeshDocument6 pagesBangladeshKhalid AhmedNo ratings yet

- Direct XCD PDFDocument12 pagesDirect XCD PDFjhuggghNo ratings yet

- 2023 01 Ansys General Hardware RecommendationsDocument22 pages2023 01 Ansys General Hardware RecommendationsShravani ZadeNo ratings yet

- CH. 1 SignalsDocument29 pagesCH. 1 SignalsSohini ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Foundation Lecture (Abdulhafiz)Document4 pagesFoundation Lecture (Abdulhafiz)desigandNo ratings yet

- EC287 - Presentation To Community Board 4-RRA 03032022Document12 pagesEC287 - Presentation To Community Board 4-RRA 03032022Christina WilkinsonNo ratings yet

- Patnership NotesDocument3 pagesPatnership NotesMario Jr ShetyNo ratings yet

- Disjuntor SF1 - Dados ElétricosDocument1 pageDisjuntor SF1 - Dados ElétricosotavioalcaldeNo ratings yet

- Sniffer Nano ManualDocument5 pagesSniffer Nano ManualMuhammad SalmanNo ratings yet

- Dealscope Google Fitbit PDFDocument1 pageDealscope Google Fitbit PDFPrasnth KumarNo ratings yet

- Notes MT Module I - KTUDocument47 pagesNotes MT Module I - KTURagesh Dudu100% (1)

- TC15M 65M Manual PDFDocument15 pagesTC15M 65M Manual PDFReciclando ChatarraNo ratings yet

- OTC107207 OptiX NG WDM Optical Layer Data Configuration ISSUE 1Document28 pagesOTC107207 OptiX NG WDM Optical Layer Data Configuration ISSUE 1ARMAND NGUETSA SONKENGNo ratings yet

- Alexander Gelman: Born: 1967 Education: Moscow Art Institute Currently Resides: New York City Selected Honors: AwardsDocument5 pagesAlexander Gelman: Born: 1967 Education: Moscow Art Institute Currently Resides: New York City Selected Honors: AwardsLaHipiNo ratings yet

- Dishwasher 2011Document20 pagesDishwasher 2011chamaljsNo ratings yet

- 2012jal PDFDocument239 pages2012jal PDFAfifah WijayaNo ratings yet

- Task 4Document6 pagesTask 4paul.rieger.1No ratings yet

- Pemberton Asian Opportunities Fund Emerges As Substantial Shareholder of SGX-Listed JukenDocument2 pagesPemberton Asian Opportunities Fund Emerges As Substantial Shareholder of SGX-Listed JukenWeR1 Consultants Pte LtdNo ratings yet

- Toll ManagementDocument44 pagesToll ManagementJay PatelNo ratings yet

- Flame Detector SiemensDocument4 pagesFlame Detector SiemensErvin BošnjakNo ratings yet

- Akira TVDocument22 pagesAkira TVErmand WindNo ratings yet

- ORLANDI Catalogue Blue en-DEDocument44 pagesORLANDI Catalogue Blue en-DEtinashemambarizaNo ratings yet

- Variable Pitch Fan System - If EquippedDocument3 pagesVariable Pitch Fan System - If EquippedEVER DAVID SAAVEDRA HUAYHUANo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Basic Concepts and Computer EvolutionDocument23 pagesChapter 1 - Basic Concepts and Computer EvolutionM KalaounNo ratings yet

- Digital Communications: Design For The Real WorldDocument19 pagesDigital Communications: Design For The Real WorldShunyi LiuNo ratings yet

- V.1 Comment Opposiiton To Defendant's Motion For Extension of Time To File AnswerDocument2 pagesV.1 Comment Opposiiton To Defendant's Motion For Extension of Time To File AnswerRhows Buergo100% (1)

- Precedents For The Reply of The Coca COla CompanyDocument3 pagesPrecedents For The Reply of The Coca COla CompanyLex OraculiNo ratings yet