Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Peer Pressure To Smoke

Peer Pressure To Smoke

Uploaded by

Jessica BaldemorCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- School Dropout QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesSchool Dropout QuestionnaireMuhammad Yaseen92% (26)

- Agents of SocializationDocument15 pagesAgents of SocializationJöhn Paul DapulangNo ratings yet

- Research On Practical Research 1Document54 pagesResearch On Practical Research 1ZOSIMO PIZONNo ratings yet

- Pellegrini 2002 Bullying, Victimization, and Sexual Harassment During The Transition To Middle SchoolDocument14 pagesPellegrini 2002 Bullying, Victimization, and Sexual Harassment During The Transition To Middle SchoolhoorieNo ratings yet

- Peer Pressure POWER POINT PRESENTATIONDocument18 pagesPeer Pressure POWER POINT PRESENTATIONJulie Rodelas100% (2)

- Systems Plus College Foundation Balibago, Angeles City, Pampanga College of NursingDocument8 pagesSystems Plus College Foundation Balibago, Angeles City, Pampanga College of NursingAly PinpinNo ratings yet

- Adolescent and Adulthood Smoking Initiation: What Is Occurring and What Now?Document5 pagesAdolescent and Adulthood Smoking Initiation: What Is Occurring and What Now?mcheung04No ratings yet

- Attitude of West Negros University Level 3 Student Nurses Towards SmokingDocument25 pagesAttitude of West Negros University Level 3 Student Nurses Towards SmokingMa Angelica AlzagaNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument25 pagesThesisivon_lozanoNo ratings yet

- Adolescence: A Physiological, Cultural and Psychological No Man'S LandDocument4 pagesAdolescence: A Physiological, Cultural and Psychological No Man'S LandNicolas GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Youth Smoking Research PaperDocument8 pagesYouth Smoking Research Paperafedtkjdz100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography FinalDocument10 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Finalmcheung04100% (1)

- Reasearch Methododlgy CIA: Vipul Pereira 1114340 Iii PsecoDocument7 pagesReasearch Methododlgy CIA: Vipul Pereira 1114340 Iii PsecosnehaoctNo ratings yet

- 6 Major Factors That Influence Teenagers To SmokeDocument2 pages6 Major Factors That Influence Teenagers To SmokeAriel VillarealNo ratings yet

- Smoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearDocument12 pagesSmoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearBernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Vandolph Thesis2.3Document254 pagesVandolph Thesis2.3Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Vandolph Thesis2.1Document246 pagesVandolph Thesis2.1Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Vandolph Thesis2.4Document287 pagesVandolph Thesis2.4Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Smoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearDocument289 pagesSmoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearBernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- A Research Study On SmokingDocument8 pagesA Research Study On SmokingMr.anonymous unknownNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument9 pagesReview of Related LiteratureJean Calubag CatalanNo ratings yet

- Youth ResearchDocument106 pagesYouth ResearchBen Dantes - AlanoNo ratings yet

- PMCH: Awareness of The Serious Consequences of Smoking Cigarettes Among Teenagers Studying in UphsdDocument27 pagesPMCH: Awareness of The Serious Consequences of Smoking Cigarettes Among Teenagers Studying in UphsdNakul SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Biblo Annat DraftDocument6 pagesBiblo Annat Draftmcheung04No ratings yet

- Thesis EnglishIDocument16 pagesThesis EnglishIjpalmoiteNo ratings yet

- Try and Try Again: Qualitative Insights Into Adolescent Smoking Experimentation and Notions of AddictionDocument8 pagesTry and Try Again: Qualitative Insights Into Adolescent Smoking Experimentation and Notions of AddictionChanelle Honey VicedoNo ratings yet

- Senior ThesisDocument10 pagesSenior ThesisSamuel BatesNo ratings yet

- WRT 1020 Cause and Effect Paper - SmokingDocument10 pagesWRT 1020 Cause and Effect Paper - Smokingapi-248441390No ratings yet

- Method of Research (Final Na Ito)Document86 pagesMethod of Research (Final Na Ito)Jean Madariaga BalanceNo ratings yet

- Alcoholism Research Paper WritingDocument7 pagesAlcoholism Research Paper Writingafeaupyen100% (1)

- 3B - Group 6 - Reading TextDocument5 pages3B - Group 6 - Reading TextThắm ThắmNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Cigarette SmokingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Cigarette Smokingfrvkuhrif100% (1)

- Socsci 1Document27 pagesSocsci 1Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Wala KwnetaDocument11 pagesWala KwnetaJohn Vincent Consul CameroNo ratings yet

- Attitude of West Negros UniversityDocument27 pagesAttitude of West Negros UniversityjhilyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Teenage Alcohol AbuseDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Teenage Alcohol Abuseh01xzacm100% (1)

- Why Do Adolescents DrinkDocument6 pagesWhy Do Adolescents DrinkchukisaliNo ratings yet

- Alcohol ResearcDocument85 pagesAlcohol ResearcEmmanuel de LeonNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument13 pagesResearch ProposalUsman AliNo ratings yet

- The Use of Alcohol and CigretteDocument5 pagesThe Use of Alcohol and CigretteHIMANSHU VERMANo ratings yet

- Extraversion As Personal Trait Effect To Drug AbuseDocument11 pagesExtraversion As Personal Trait Effect To Drug Abusepaul havardNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Abuse Research PaperDocument7 pagesAlcohol Abuse Research Paperfzpabew4100% (1)

- Alcoholism Research Paper ExampleDocument7 pagesAlcoholism Research Paper Exampleaflbrpwan100% (1)

- Smoking and Vaping As A Social Anxiety RelieverDocument36 pagesSmoking and Vaping As A Social Anxiety RelieverLarribelle LagonillaNo ratings yet

- Drugs: Statistics and ProbabilityDocument27 pagesDrugs: Statistics and ProbabilityNeha ArifNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Teenage DrinkingDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Teenage Drinkingfyrc79tv100% (1)

- Research AnalysisDocument8 pagesResearch Analysisapi-666664257No ratings yet

- The World of Substance Abuse and Adolescents 1Document11 pagesThe World of Substance Abuse and Adolescents 1api-746607519No ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document23 pagesChapter 3Sandeep K RNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Alcoholism OutlineDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Alcoholism Outlinem0d1p1fuwub2100% (1)

- Research Paper On Teenage Drug UseDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Teenage Drug Useiangetplg100% (1)

- Chapter I and Chapter II ResearchDocument20 pagesChapter I and Chapter II ResearchMon HaleNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Risk Behaviour, Violence, Health, Well-Being, Peer Relation, Parent RelationDocument10 pagesKeywords: Risk Behaviour, Violence, Health, Well-Being, Peer Relation, Parent RelationmandaNo ratings yet

- 071-005 Factor AssociatedDocument5 pages071-005 Factor AssociatedAzlisonGuilaboBawangNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Absenteeism in The Academic Performance of Smaw 12 StudentsDocument24 pagesThe Effects of Absenteeism in The Academic Performance of Smaw 12 Studentsmadonnamanzan081No ratings yet

- Shsconf Erpa2018 01006Document10 pagesShsconf Erpa2018 01006Jodie Junio BaladadNo ratings yet

- Research Analysis FinalDocument8 pagesResearch Analysis Finalapi-666664257No ratings yet

- Exercise Addiction Research PaperDocument6 pagesExercise Addiction Research Paperzejasyvkg100% (1)

- Module 9 Personal RelationshipDocument13 pagesModule 9 Personal Relationshipprincess3canlasNo ratings yet

- Essay On Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers PDFDocument4 pagesEssay On Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers PDFDamien Ashwood100% (1)

- Stress-Proof Your Teen: Helping Your Teen Manage Stress and Build Healthy HabitsFrom EverandStress-Proof Your Teen: Helping Your Teen Manage Stress and Build Healthy HabitsNo ratings yet

- The Everything Parent's Guide to Teenage Addiction: A Comprehensive and Supportive Reference to Help Your Child Recover from AddictionFrom EverandThe Everything Parent's Guide to Teenage Addiction: A Comprehensive and Supportive Reference to Help Your Child Recover from AddictionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- January 2018 February 2018: Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri SatDocument6 pagesJanuary 2018 February 2018: Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri SatJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

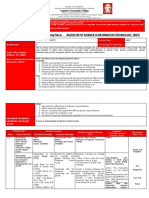

- Name of Parent/Guardian Name of Student Current Grade Level Contact NumberDocument3 pagesName of Parent/Guardian Name of Student Current Grade Level Contact NumberJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

- Price ListDocument1 pagePrice ListJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

- Drive 9.8 KM, 25 Min Valenzuela To Walter Mart Mall North EdsaDocument2 pagesDrive 9.8 KM, 25 Min Valenzuela To Walter Mart Mall North EdsaJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

- Political Socialization Is A Lifelong Process by Which People Form Their Ideas About Politics and Acquire Political ValuesDocument2 pagesPolitical Socialization Is A Lifelong Process by Which People Form Their Ideas About Politics and Acquire Political ValuesAwais KhanNo ratings yet

- IELTS Passport Task 1 - Slide Bu I 9Document12 pagesIELTS Passport Task 1 - Slide Bu I 9Hoàng Minh ChiếnNo ratings yet

- The Political SelfDocument2 pagesThe Political SelfMercy Abareta100% (1)

- The Effects of Participation in Extracurricular Activities On AcaDocument171 pagesThe Effects of Participation in Extracurricular Activities On AcaCharisa SimbajonNo ratings yet

- Youth ThemeDocument7 pagesYouth ThemeCecelia ChoirNo ratings yet

- Final Reflective Essay JenayamcgeeDocument3 pagesFinal Reflective Essay Jenayamcgeeapi-282139870No ratings yet

- Isi Artikel 871892853119Document21 pagesIsi Artikel 871892853119xoxoNo ratings yet

- PERDEV - Q1 - Mod3 - Why Am I Like ThisDocument35 pagesPERDEV - Q1 - Mod3 - Why Am I Like ThisAzariel BendyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-4Document11 pagesChapter 1-4Dannielle CabangNo ratings yet

- Gad 2Document35 pagesGad 2cyrelmark cuarioNo ratings yet

- Peer PressureDocument3 pagesPeer Pressuresalbina arabiNo ratings yet

- Title-Defense (3psyc) (Banaag)Document13 pagesTitle-Defense (3psyc) (Banaag)Rose Anne ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- MAKALAH BULLYING Adi - Id.enDocument21 pagesMAKALAH BULLYING Adi - Id.enSupriadi ArfahNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Influences and Educational Aspirations in 12 Countries - The Importance of Institutional ContextDocument25 pagesInterpersonal Influences and Educational Aspirations in 12 Countries - The Importance of Institutional Context方科惠No ratings yet

- Litrev 5Document16 pagesLitrev 5Selly MauriceNo ratings yet

- 0495/11 Sociology: Cambridge International ExaminationsDocument4 pages0495/11 Sociology: Cambridge International ExaminationsLaela NovitriNo ratings yet

- Effects of Peer Pressure On Grade 12 Students in Phinma-Araullo UniversityDocument60 pagesEffects of Peer Pressure On Grade 12 Students in Phinma-Araullo UniversityJayren MindanaoNo ratings yet

- Course-Guide-Gender and SocietyDocument11 pagesCourse-Guide-Gender and SocietyFlor Laput100% (1)

- Examples of Positive Youth Development Program Activities Aligned With PYD Features, Mapped To A Socio-Ecological ModelDocument8 pagesExamples of Positive Youth Development Program Activities Aligned With PYD Features, Mapped To A Socio-Ecological ModelLeah LaroyaNo ratings yet

- How Are Attitudes FormedDocument3 pagesHow Are Attitudes FormedMehul MehtaNo ratings yet

- Values, Attitudes and Job SatisfactionDocument18 pagesValues, Attitudes and Job Satisfactionjerico garciaNo ratings yet

- FilipinoDocument3 pagesFilipinoPedrito FajardoNo ratings yet

- LiteratureDocument6 pagesLiteratureReshel Mae PontoyNo ratings yet

- DefilementDocument6 pagesDefilementcrutagonya391No ratings yet

- Enhancing Peer Support - Liane Angel KalacasDocument18 pagesEnhancing Peer Support - Liane Angel KalacasEdgardo T. GaliciaNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument11 pagesResearch MethodologyBoguus BoguusNo ratings yet

Peer Pressure To Smoke

Peer Pressure To Smoke

Uploaded by

Jessica BaldemorOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Peer Pressure To Smoke

Peer Pressure To Smoke

Uploaded by

Jessica BaldemorCopyright:

Available Formats

y

Peer pressure to smoke: the meaning depends on the method

1. L. Michell and 2. P. West + Author Affiliations 1. MRC Medical Sociology Unit, 6 Lilybank Gardens Glasgow G12 8RZ, UK

y y

Received May 30, 1995. Accepted September 10, 1995.

Abstract

This paper is concerned with the meaning and the processes of peer pressure in relation to smoking behaviour amongst pre-adolescent and adolescent pupils. Previous research suggests that children who smoke cause their non-smoking peers to take up the habit through strategies such as coercion, teasing, bullying and rejection from a desired group. In this study different methods elicited different accounts of initial smoking situations from the same pupils. While role-play elicited stereotypical scenes of coercion and bullying, results from a self-complete questionnaire and focus groups conflicted with these accounts and suggested that the process was more complex and included strong elements of self-determined behaviour. This study highlights the problems of using a single research method to understand complex processes. Results suggest that individuals play a more active role in starting to smoke than has previously been acknowledged and that social processes other than peer pressure need to be taken into account. Possible implications for health education programmes are far reaching.

How Peer Pressure influences smoking

Peer pressure is one of the most widespread causes cited by young people to start smoking. An individuals peers are the group of people of similar age. Frequently they have identical interests like the individual or may attend the same school or college. Generally an individual indulges in activities likely to be appreciated by his or her peers. Occasionally, individuals try to appease their peers to be a part of the group or do so, in order to eliminate the prospect of being bullied. Individuals may be subjected to coercion from their peers

to smoke. Not only is smoking detrimental for an individuals health, its also unlawful for individuals to purchase cigarettes if he or she is below sixteen years of age. Smoking violates the regulation of schools. Individuals would do well to refrain from this habit inside the school premises even if his or her peers encourage the individual to do so. A large number of smokers try to keep their children away from the harmful habit of smoking. They do not want them to suffer from health complications like them. If an individual is pressured by his or her peer to smoke, then that person is not an ideal friend. If he or she is an ideal friend, that individual would never bully his friend to smoke. In case an individual starts smoking casually, it is imperative for the individual to quit smoking before becoming a regular smoker. If an individual is bullied it is crucial for the individual to talk to someone for example a parent, teacher, or friend for help. During adolescence, children try to declare their independence and discover their identity. However, they still yearn for the endorsement of their action by peers. They are often unnecessarily bothered about the prospect of being discarded. It has been established that adolescents act in accordance with their observation which do not at all times correspond to reality. As far as smoking cigarettes is concerned, children are undoubtedly guided by the action of their peers. Studies have revealed that the rate of smoking among children with three or more friends who smoke is 10 times greater in comparison to the rate among children who do not have friends who smoke.

5.8 The smoking behaviour of peers, and peer attitudes and norms

Show / hide chapter menu Smoking during adolescence is primarily a social activity,7 and research has consistently identified peer group influences as a significant factor in uptake of smoking.1, 10, 11, 44, 84 Peer groups may variously be defined as best friendships, romantic attachments, small social 'networks' and larger social 'crowds'.[6]91 Each of these types of peer group may influence the decision to smoke or not to smoke.91 Just how influential peer pressure is, however, remains a matter of some debate. Some commentators have argued that the importance of peer influence has been overestimated, and that the clustering of smoking behaviour within peer groups could be because adolescents seek

out friendships with individuals who share similar interests, of which smoking may be just one signifier.92, 93 In a review of peer influence and smoking behaviour, Michell94 concluded that the effect of peer pressure as an influence on adolescent health behaviour is not proven, and is in practice, very complex to decipher. It is important to understand that young people are not a homogeneous group, and that there are distinct peer clusters who smoke and do so for different reasons.94 It is probable that peer influences both interact with and are compounded by a host of other predictive factors, and that the nature of peer influences on smoking changes over time and across social and cultural groupings. Recent research also suggests that peer influences may vary in importance at differing points along the adolescent continuum, with the influence of close friends' smoking having most impact in earlier adolescence.95 The common perception that 'peer group pressure' equates with open coercion is not necessarily the case. Initiating smoking may arise as a response to more subtle influences, such as being a means of facilitating acceptance and bonding, and avoiding exclusion from peer groups.7, 91 Research from Western Australia in 2004 found that some adolescent experimenters and smokers saw trying a cigarette in the spirit of 'joining in' or 'giving it a go.' However, the same research found that young people of Indigenous or lower SES background were much more likely to describe overt peer pressure or inducement to try smoking.54 Being 'cool' is important to teenagers96 although what is deemed to be cool also changes across time, peer groups and social contexts. Smoking has traditionally been viewed as one of the badges of 'coolness' among teenagers.97 While 'coolness' is still identified by young people as one of the reasons why some of their peers smoke,98 research undertaken in Western Australia in 2004 suggests that the inverse is increasingly true, with those who smoke often regarded as 'losers' or 'trying too hard to be cool'.54 Refusing an offer of cigarettes or declaring that 'I don't smoke' is increasingly socially acceptable and normative among many youth cohorts.54 Among groups with a negative prevailing attitude to smoking, peer influence may, of course, deter uptake of smoking.7, 91 British research has found that forming romantic attachments ('dating') at an earlier age is a predictor for becoming a smoker later, independent of other possible confounding factors. The authors speculate that dating and smoking behaviours may be connected by a desire to appear to be more grown up,99 which is consistent with tobacco industry advertising to link its products with sex appeal and popularity.100 Research also suggests that young people who are lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB) have a higher risk of taking up smoking.101, 102 Reasons for this could be that LGB teenagers may be at greater risk of experiencing loneliness, isolation, harassment and depression. The LGB population has also been specifically targeted in tobacco advertising.102 Young smokers tend to congregate together, and also to overestimate the extent of smoking in their own age group, giving them a distorted sense of what is normal behaviour.10, 44, 56 The National Drug Strategy Household Survey for 20043 found that about two-thirds (64%) of recent smokers aged 1215 said that 'all or most' of their friends and acquaintances were smokers as well. A further 20% said that 'about half' of their peer group were smokers. Only 1% of smokers in this age group said that none of their friends and acquaintances smoked. The effect declined with increasing age, with 28% of smokers aged 20 years or older reporting that 'all or most' of

their friends and acquaintances were smokers, 32% saying 'around half were', and 39% saying only a few of their peer group smoked. Adolescents who think that smoking is normative and that most of their peers smoke, are more likely to start smoking.4, 7, 10

5.8.1 Influence of gender

A large number of studies have examined whether boys and girls are similarly affected by the various factors that influence smoking behaviour. In a major review of the literature, the US Surgeon General's report for 2001 (Women and smoking)10 concluded that 'Most risk factors for smoking initiation appear to be similar among girls and boys.' (p.477) However, the review did find that girls may be more likely to be influenced by positive images of smoking, perceptions about smoking and weight control, and the belief that smoking helps to improve mood. There was also some evidence that girls are more likely to smoke than boys out of rebelliousness, rejection of conventional values, lack of religious conviction, poor self-esteem and emotional distress. Other research has proposed that males are more likely to smoke as a result of 'psychosocial' factors (such as risk-taking, rebelliousness, self-esteem and coping ability), whereas girls tended more to be influenced by 'environmental' factors such as parental smoking habits, peer group attitudes and behaviours. The strength of the relative influence of these factors is likely to change during teenage years.103 Koval et al have found that psychosocial factors are more closely associated with smoking in young teenage girls than in older girls, who are more influenced by attitude variables (including beliefs about smoking); while younger boys are less susceptible to the influences of both psychosocial factors and environmental variables than older males. Australian studies have reported that uptake of smoking in adolescent girls is strongly related to a desire to adopt and reinforce their reputation among a specific peer group,104 and that strength of self-concept in girls (defined as how an individual perceives her physical presentation and appearance to others) is more closely connected with increased likelihood of smoking than in boys.105 The authors of this study speculate that environmental pressures on adolescent girls to be self-confident, socially aggressive and sexually precocious may lead to cigarette smoking, in an effort to boost physical self-concept.105

5.8.1.1 Do concerns about body weight influence the uptake of smoking?

The perception that smoking depresses appetite, hence assisting with weight control, has long been considered a possible enticement for smoking, especially among females.[7] Over many decades the tobacco industry has overtly targeted the female market with brands and imagery connecting cigarettes with a slim and shapely female form.10, 106, 107 A large number of studies have investigated the relationship between adolescent smoking and body weight. A review by Potter et al108 analyses 55 studies published between 19802003. Taking into account the wide variation in study methodologies, this review concluded that there was some evidence that:

y

young smokers were more likely to perceive that they were overweight

y y

some adolescents smoked because they thought it would help with weight control, and that adolescent smokers were more likely to have engaged in dieting, the evidence being strongest for girls.

Research from Western Australia54 has shown that young people (both smokers and nonsmokers) cite 'to be thin' as a reason for smokin

5.1 Introduction

Show / hide chapter menu Most smokers become addicted in their teenage years1 and most Australian teenagers who become smokers obtain their first cigarette from a friend or an acquaintance.2, 3 Smoking prevalence escalates rapidly during adolescence, from 2% of 12-year-olds to 18% of 17-yearolds among Australian teenagers in 2005. Fewer than 10% of 17-year-old current[1] and daily smokers say that they definitely intend to quit smoking in the future. This strongly suggests that most Australian students who smoked in their final year of school in 2005 will continue smoking beyond their school years.2 Young people can become addicted to cigarettes at very low consumption levels, and after smoking only a few cigarettes.4 British research has found that smoking just a single cigarette at the age of 11 can leave a child susceptible to later uptake of regular smoking, even after a period of three or more years. This could be due to neurobiological factors, or social or personal traits.5 The first 18 sections of this chapter provide discussion about stages in the uptake of smoking, and the range of factors that influence an individual's decision whether or not to start smoking. While the various threads are discussed separately, it is important to remember that in reality many of these factors are interconnected and should not be considered in isolation. The second part of this chapter, commencing with Section 5.19, examines ways of countering these influences to help prevent the uptake of smoking.

You might also like

- School Dropout QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesSchool Dropout QuestionnaireMuhammad Yaseen92% (26)

- Agents of SocializationDocument15 pagesAgents of SocializationJöhn Paul DapulangNo ratings yet

- Research On Practical Research 1Document54 pagesResearch On Practical Research 1ZOSIMO PIZONNo ratings yet

- Pellegrini 2002 Bullying, Victimization, and Sexual Harassment During The Transition To Middle SchoolDocument14 pagesPellegrini 2002 Bullying, Victimization, and Sexual Harassment During The Transition To Middle SchoolhoorieNo ratings yet

- Peer Pressure POWER POINT PRESENTATIONDocument18 pagesPeer Pressure POWER POINT PRESENTATIONJulie Rodelas100% (2)

- Systems Plus College Foundation Balibago, Angeles City, Pampanga College of NursingDocument8 pagesSystems Plus College Foundation Balibago, Angeles City, Pampanga College of NursingAly PinpinNo ratings yet

- Adolescent and Adulthood Smoking Initiation: What Is Occurring and What Now?Document5 pagesAdolescent and Adulthood Smoking Initiation: What Is Occurring and What Now?mcheung04No ratings yet

- Attitude of West Negros University Level 3 Student Nurses Towards SmokingDocument25 pagesAttitude of West Negros University Level 3 Student Nurses Towards SmokingMa Angelica AlzagaNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument25 pagesThesisivon_lozanoNo ratings yet

- Adolescence: A Physiological, Cultural and Psychological No Man'S LandDocument4 pagesAdolescence: A Physiological, Cultural and Psychological No Man'S LandNicolas GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Youth Smoking Research PaperDocument8 pagesYouth Smoking Research Paperafedtkjdz100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliography FinalDocument10 pagesAnnotated Bibliography Finalmcheung04100% (1)

- Reasearch Methododlgy CIA: Vipul Pereira 1114340 Iii PsecoDocument7 pagesReasearch Methododlgy CIA: Vipul Pereira 1114340 Iii PsecosnehaoctNo ratings yet

- 6 Major Factors That Influence Teenagers To SmokeDocument2 pages6 Major Factors That Influence Teenagers To SmokeAriel VillarealNo ratings yet

- Smoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearDocument12 pagesSmoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearBernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Vandolph Thesis2.3Document254 pagesVandolph Thesis2.3Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Vandolph Thesis2.1Document246 pagesVandolph Thesis2.1Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Vandolph Thesis2.4Document287 pagesVandolph Thesis2.4Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Smoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearDocument289 pagesSmoking: Psychological and Social Influences: One-Of-A-Kind MenswearBernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- A Research Study On SmokingDocument8 pagesA Research Study On SmokingMr.anonymous unknownNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument9 pagesReview of Related LiteratureJean Calubag CatalanNo ratings yet

- Youth ResearchDocument106 pagesYouth ResearchBen Dantes - AlanoNo ratings yet

- PMCH: Awareness of The Serious Consequences of Smoking Cigarettes Among Teenagers Studying in UphsdDocument27 pagesPMCH: Awareness of The Serious Consequences of Smoking Cigarettes Among Teenagers Studying in UphsdNakul SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Biblo Annat DraftDocument6 pagesBiblo Annat Draftmcheung04No ratings yet

- Thesis EnglishIDocument16 pagesThesis EnglishIjpalmoiteNo ratings yet

- Try and Try Again: Qualitative Insights Into Adolescent Smoking Experimentation and Notions of AddictionDocument8 pagesTry and Try Again: Qualitative Insights Into Adolescent Smoking Experimentation and Notions of AddictionChanelle Honey VicedoNo ratings yet

- Senior ThesisDocument10 pagesSenior ThesisSamuel BatesNo ratings yet

- WRT 1020 Cause and Effect Paper - SmokingDocument10 pagesWRT 1020 Cause and Effect Paper - Smokingapi-248441390No ratings yet

- Method of Research (Final Na Ito)Document86 pagesMethod of Research (Final Na Ito)Jean Madariaga BalanceNo ratings yet

- Alcoholism Research Paper WritingDocument7 pagesAlcoholism Research Paper Writingafeaupyen100% (1)

- 3B - Group 6 - Reading TextDocument5 pages3B - Group 6 - Reading TextThắm ThắmNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Cigarette SmokingDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Cigarette Smokingfrvkuhrif100% (1)

- Socsci 1Document27 pagesSocsci 1Bernardo Villavicencio VanNo ratings yet

- Wala KwnetaDocument11 pagesWala KwnetaJohn Vincent Consul CameroNo ratings yet

- Attitude of West Negros UniversityDocument27 pagesAttitude of West Negros UniversityjhilyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Teenage Alcohol AbuseDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Teenage Alcohol Abuseh01xzacm100% (1)

- Why Do Adolescents DrinkDocument6 pagesWhy Do Adolescents DrinkchukisaliNo ratings yet

- Alcohol ResearcDocument85 pagesAlcohol ResearcEmmanuel de LeonNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument13 pagesResearch ProposalUsman AliNo ratings yet

- The Use of Alcohol and CigretteDocument5 pagesThe Use of Alcohol and CigretteHIMANSHU VERMANo ratings yet

- Extraversion As Personal Trait Effect To Drug AbuseDocument11 pagesExtraversion As Personal Trait Effect To Drug Abusepaul havardNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Abuse Research PaperDocument7 pagesAlcohol Abuse Research Paperfzpabew4100% (1)

- Alcoholism Research Paper ExampleDocument7 pagesAlcoholism Research Paper Exampleaflbrpwan100% (1)

- Smoking and Vaping As A Social Anxiety RelieverDocument36 pagesSmoking and Vaping As A Social Anxiety RelieverLarribelle LagonillaNo ratings yet

- Drugs: Statistics and ProbabilityDocument27 pagesDrugs: Statistics and ProbabilityNeha ArifNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Teenage DrinkingDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Teenage Drinkingfyrc79tv100% (1)

- Research AnalysisDocument8 pagesResearch Analysisapi-666664257No ratings yet

- The World of Substance Abuse and Adolescents 1Document11 pagesThe World of Substance Abuse and Adolescents 1api-746607519No ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document23 pagesChapter 3Sandeep K RNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Alcoholism OutlineDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Alcoholism Outlinem0d1p1fuwub2100% (1)

- Research Paper On Teenage Drug UseDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Teenage Drug Useiangetplg100% (1)

- Chapter I and Chapter II ResearchDocument20 pagesChapter I and Chapter II ResearchMon HaleNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Risk Behaviour, Violence, Health, Well-Being, Peer Relation, Parent RelationDocument10 pagesKeywords: Risk Behaviour, Violence, Health, Well-Being, Peer Relation, Parent RelationmandaNo ratings yet

- 071-005 Factor AssociatedDocument5 pages071-005 Factor AssociatedAzlisonGuilaboBawangNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Absenteeism in The Academic Performance of Smaw 12 StudentsDocument24 pagesThe Effects of Absenteeism in The Academic Performance of Smaw 12 Studentsmadonnamanzan081No ratings yet

- Shsconf Erpa2018 01006Document10 pagesShsconf Erpa2018 01006Jodie Junio BaladadNo ratings yet

- Research Analysis FinalDocument8 pagesResearch Analysis Finalapi-666664257No ratings yet

- Exercise Addiction Research PaperDocument6 pagesExercise Addiction Research Paperzejasyvkg100% (1)

- Module 9 Personal RelationshipDocument13 pagesModule 9 Personal Relationshipprincess3canlasNo ratings yet

- Essay On Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers PDFDocument4 pagesEssay On Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers PDFDamien Ashwood100% (1)

- Stress-Proof Your Teen: Helping Your Teen Manage Stress and Build Healthy HabitsFrom EverandStress-Proof Your Teen: Helping Your Teen Manage Stress and Build Healthy HabitsNo ratings yet

- The Everything Parent's Guide to Teenage Addiction: A Comprehensive and Supportive Reference to Help Your Child Recover from AddictionFrom EverandThe Everything Parent's Guide to Teenage Addiction: A Comprehensive and Supportive Reference to Help Your Child Recover from AddictionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- January 2018 February 2018: Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri SatDocument6 pagesJanuary 2018 February 2018: Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri SatJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

- Name of Parent/Guardian Name of Student Current Grade Level Contact NumberDocument3 pagesName of Parent/Guardian Name of Student Current Grade Level Contact NumberJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

- Price ListDocument1 pagePrice ListJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

- Drive 9.8 KM, 25 Min Valenzuela To Walter Mart Mall North EdsaDocument2 pagesDrive 9.8 KM, 25 Min Valenzuela To Walter Mart Mall North EdsaJessica BaldemorNo ratings yet

- Political Socialization Is A Lifelong Process by Which People Form Their Ideas About Politics and Acquire Political ValuesDocument2 pagesPolitical Socialization Is A Lifelong Process by Which People Form Their Ideas About Politics and Acquire Political ValuesAwais KhanNo ratings yet

- IELTS Passport Task 1 - Slide Bu I 9Document12 pagesIELTS Passport Task 1 - Slide Bu I 9Hoàng Minh ChiếnNo ratings yet

- The Political SelfDocument2 pagesThe Political SelfMercy Abareta100% (1)

- The Effects of Participation in Extracurricular Activities On AcaDocument171 pagesThe Effects of Participation in Extracurricular Activities On AcaCharisa SimbajonNo ratings yet

- Youth ThemeDocument7 pagesYouth ThemeCecelia ChoirNo ratings yet

- Final Reflective Essay JenayamcgeeDocument3 pagesFinal Reflective Essay Jenayamcgeeapi-282139870No ratings yet

- Isi Artikel 871892853119Document21 pagesIsi Artikel 871892853119xoxoNo ratings yet

- PERDEV - Q1 - Mod3 - Why Am I Like ThisDocument35 pagesPERDEV - Q1 - Mod3 - Why Am I Like ThisAzariel BendyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-4Document11 pagesChapter 1-4Dannielle CabangNo ratings yet

- Gad 2Document35 pagesGad 2cyrelmark cuarioNo ratings yet

- Peer PressureDocument3 pagesPeer Pressuresalbina arabiNo ratings yet

- Title-Defense (3psyc) (Banaag)Document13 pagesTitle-Defense (3psyc) (Banaag)Rose Anne ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- MAKALAH BULLYING Adi - Id.enDocument21 pagesMAKALAH BULLYING Adi - Id.enSupriadi ArfahNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Influences and Educational Aspirations in 12 Countries - The Importance of Institutional ContextDocument25 pagesInterpersonal Influences and Educational Aspirations in 12 Countries - The Importance of Institutional Context方科惠No ratings yet

- Litrev 5Document16 pagesLitrev 5Selly MauriceNo ratings yet

- 0495/11 Sociology: Cambridge International ExaminationsDocument4 pages0495/11 Sociology: Cambridge International ExaminationsLaela NovitriNo ratings yet

- Effects of Peer Pressure On Grade 12 Students in Phinma-Araullo UniversityDocument60 pagesEffects of Peer Pressure On Grade 12 Students in Phinma-Araullo UniversityJayren MindanaoNo ratings yet

- Course-Guide-Gender and SocietyDocument11 pagesCourse-Guide-Gender and SocietyFlor Laput100% (1)

- Examples of Positive Youth Development Program Activities Aligned With PYD Features, Mapped To A Socio-Ecological ModelDocument8 pagesExamples of Positive Youth Development Program Activities Aligned With PYD Features, Mapped To A Socio-Ecological ModelLeah LaroyaNo ratings yet

- How Are Attitudes FormedDocument3 pagesHow Are Attitudes FormedMehul MehtaNo ratings yet

- Values, Attitudes and Job SatisfactionDocument18 pagesValues, Attitudes and Job Satisfactionjerico garciaNo ratings yet

- FilipinoDocument3 pagesFilipinoPedrito FajardoNo ratings yet

- LiteratureDocument6 pagesLiteratureReshel Mae PontoyNo ratings yet

- DefilementDocument6 pagesDefilementcrutagonya391No ratings yet

- Enhancing Peer Support - Liane Angel KalacasDocument18 pagesEnhancing Peer Support - Liane Angel KalacasEdgardo T. GaliciaNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument11 pagesResearch MethodologyBoguus BoguusNo ratings yet