Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Surgical Ward Journal

Surgical Ward Journal

Uploaded by

Ma Genille Samporna SabalOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Surgical Ward Journal

Surgical Ward Journal

Uploaded by

Ma Genille Samporna SabalCopyright:

Available Formats

Abstract Objective: To assess what proportion of surgical malpractice claims might be prevented by the use of a surgical safety checklist.

Background: Surgical disciplines are overrepresented in the distribution of adverse events. The recently described multidisciplinary SURgical PAtient Safety System (SURPASS) checklist covers the entire surgical pathway from admission to discharge and is being validated in various ways. Malpractice claims constitute an important source of information on adverse events. In this study, surgical malpractice claims were evaluated in detail to assess the proportion and nature of claims that might have been prevented if the SURPASS checklist had been used. Methods: A retrospective claim record review was performed using the database of the largest Dutch insurance company for medical liability. All accepted or settled closed surgical malpractice claims filed as a consequence of an incident that occurred between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2005 were included. Data on the type and outcome of the incident and contributing factors were extracted. All contributing factors were compared to the SURPASS checklist to assess which incidents the checklist might have prevented. Results: We included 294 claims. Failure in diagnosis and peroperative damage were the most common types of incident; cognitive contributing factors were present in two-thirds of claims. Of a total of 412 contributing factors, 29% might have been intercepted by the SURPASS checklist. The checklist might have prevented 40% of deaths and 29% of incidents leading to permanent damage. Conclusion: Nearly one-third of all contributing factors in accepted surgical malpractice claims of patients that had undergone surgery might have been intercepted by using a comprehensive surgical safety checklist. A considerable amount of damage, both physical and financial, is likely to be prevented by using the SURPASS checklist.

Patrick Jason R. Cortes BSN3-G

Prevention of Surgical Malpractice Claims by Use of a Surgical Safety Checklist

Eefje N. de Vries, MD, PhD; Manon P. Eikens-Jansen, MSc; Alice M. Hamersma, MSc; Susanne M. Smorenburg, MD, PhD; Dirk J. Gouma, MD, PhD; Marja A. Boermeester, MD, PhD

Introduction Nearly 1 in every 10 patients admitted to a hospital will undergo an adverse event. The consequences of these events range from temporary disability to death. Ever since this fact has been recognized, many studies have attempted to shed light on the incidence, nature, causes and consequences of adverse event and medical errors. Most of these studies have shown that surgical disciplines are overrepresented in the distribution of adverse events; almost two-thirds of inhospital events are associated with a surgical provider. To improve surgical patient safety, numerous interventions have been proposed, among them the use of checklists. Recently, the use of a checklist in the operating room was shown to be associated with a significant decrease in postoperative complication and mortality rates. However, several studies have shown that the majority of surgical errors occur outside of the operating room. This perception formed the basis for the SURgical PAtient Safety System (SURPASS) checklist, the development of which was initiated as early as 2004. SURPASS was developed based on literature and real-time observation data, and subsequently validated in surgical practice. SURPASS is a surgical safety checklist that covers the entire surgical pathway from admission to discharge. It aims to improve surgical patient safety by providing a frame for the surgical pathway and promoting interdisciplinary communication. The checklist is split up into the different stages of the pathway (preoperative ward, operating room, recovery or intensive care unit, postoperative ward, and discharge) and is multidisciplinary: ward doctor, nurse, surgeon, anaesthesiologist, and operating assistant are all responsible for completion of parts of the checklist . The external validation of SURPASS is being performed in various ways: by observation techniques, by real-time registration of intercepted incidents, and by studying the effect of the checklist on patient outcomes in a multicenter setting. Malpractice claims constitute an interesting supplement to the above-mentioned methods. Although not every malpractice claim is the consequence of an adverse event, they provide a broad catchment point for information on medical errors and adverse events, represent large groups of patients and focus on adverse events that led to serious outcomes. In the present study, surgical malpractice claims were evaluated in detail to assess the proportion and nature of claims that might have been prevented if the SURPASS checklist had been used.

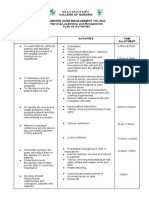

Methods Record Selection A retrospective record review was performed using the database of MediRisk, the largest Dutch insurance company for medical liability. MediRisk insures approximately 70% of all Dutch general hospitals. The insured institutes are broadly representative of the teaching and nonteaching hospitals, with the exception of all 8 academic hospitals, none of which are insured by MediRisk. All malpractice claims filed as a consequence of an incident that occurred between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2005 were reviewed. The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) claim was filed against a discipline involved in care for surgical patients (including anesthesiology, surgical residents working in the emergency department and nursing staff on a surgical ward), (2) claim was closed, (3) claim had been accepted or settled, and (4) patient had undergone surgery. Claims that did not involve a discipline involved in care for surgical patients, had not yet been closed or had been rejected, or concerned patients who had not undergone surgery, were excluded. Data Collection Of the included claims, all relevant documents were reviewed, including medical and nursing records, legal documents, and experts' assessments. The following data were extracted from the file: age, gender, the discipline, or department against which the claim was filed, and details of the incident: the type of incident, contributing factors, and the timing and outcome of the incident. Incident Classification Each incident was classified in 1 of 10 types, based on types of incidents described in the literature to date. Subsequently, the most prominent contributing factors were identified, to a maximum of 2 factors per incident. The categories in which these contributing factors were arranged, were based on published classifications of causes of surgical error. Next, a comparison was made of contributing factors and items on the SURPASS checklist. When a contributing factor corresponded to a checklist item, this factor might have been prevented had the checklist been used. The timing of each contributing factor was assessed as follows: preoperative in the outpatient clinic or emergency department, preoperative during hospital admission, peroperative, postoperative during hospital admission or postoperative during outpatient monitoring. Finally, the outcome of each incident was classified according to the classification of the Dutch National Surgical Adverse Event Registration (LHCR).[19,21] This classification includes 4 grades: first is "temporary disability, no reoperation required," second is "temporary disability, resolved after reoperation," third is "permanent disability," and fourth is "death". These categories correspond to grades in the recently described Accordion Severity Grading System, although an extra category of "permanent disability" is present in the LHCR. Results Patient Characteristics and Type of Incident Of 2128 claims filed as a consequence of incidents that occurred between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2005, 294 claims fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the present study. The median age of claimants was 52 years and over half were female. The majority of claims were filed against general surgery (33%) and orthopaedic surgery

(15%). A failure in diagnosis (26%) or treatment (13%), peroperative damage (20%), wrong side (2%), wrong site (7%), wrong procedure (6%) or wrong patient (1%) constituted the majority of incidents Contributing Factors and Correspondence to SURPASS Cognitive factors were present in two-thirds of all claims. "Error in judgment," "failure of vigilance/memory" and "failure in communication between care providers" were the most frequent contributing factors (29%, 16%, and 16%, respectively). Of a total of 412 contributing factors, 29% corresponded to an item on the SURPASS checklist and might have been intercepted by using the checklist. In the categories, "no adherence to marking or other protocol," failure in communication between care providers," "no informed consent," "insufficient preoperative information," and "material/equipment/instruments not present" a large proportion was covered by SURPASS items. Timing and Outcome The majority of incidents occurred as a consequence of preoperative or peroperative factors. When looking only at the contributing factors during hospital admission, 36% corresponded to an item on the SURPASS checklist. In the preoperative stage, this percentage was as high as 69%. When looking at the outcome of the incidents, 31% led to temporary disability without reoperation. More than a third of incidents (37%) required a reoperation to be resolved and 29% led to permanent disability, whereas 3% was fatal. In 40% of deaths and 29% of incidents leading to permanent damage, at least 1 contributing factor corresponded to an item on the checklist and might have been prevented by using SURPASS. Discussion This retrospective review of 294 surgical malpractice claims showed that the most common type of incident leading to a claim was failure in diagnosis or peroperative damage. Of the 94 incidents that led to permanent disability or death, 30% might have been prevented if the SURPASS checklist had been used. The most common contributing factor was error in judgment. In contrast, roughly a third of incidents were due to memory failures, failures in communication, failure to adhere to a protocol or the absence of equipment or material; categories that could be corrected by adopting relatively easy measures like adequate documentation, preoperative marking of the operative site and checking of availability of all implants. Many of these measures are captured in the SURPASS checklist. The checklist might have intercepted approximately 30% of contributing factors, mostly in the cognitive and communication categories. Most or all incidents that were the consequence of a failure to adhere to protocols, failure to register informed consent, failure in communication between care providers, or the preoperative absence of information or material might have been prevented by using SURPASS. Of the 70% of contributing factors that were not covered by SURPASS, some can be considered for amendments to the next version of the checklist; for example, the inclusion of sponge count protocols and preoperative registration of dental status. However, the majority of contributing factors that did not correspond to SURPASS were unfit for inclusion in a patient-specific checklist. For

instance, incidents like failure to diagnose an anastomotic leakage, a decision not to perform imaging in the ER, or administration of the wrong drug, cannot be prevented by using a patient-specific checklist like SURPASS. Other ways of standardization of processes, for example, diagnostic guidelines, barcode-guided drug administration, and ward-based pharmacy teams, may aid in preventing these incidents. Surgical malpractice claims have been studied before. In a study published in 2006, 444 surgical malpractice claims were reviewed to identify causes of surgical error and opportunities for prevention. The authors found that in 60% of cases, errors occurred in pre- or postoperative care. Error in judgment, failure of vigilance/memory and lack of technical competence were the most common contributing factors. These findings are quite similar to our results. However, in the previously mentioned study, the consequences of the surgical errors were more severe, leading to permanent damage or death in 65% of cases. This might reflect the different litigation systems in place in the United States and the Netherlands; malpractice claims in the Netherlands are handled through an arbitration system, there are no jury trials and the patient can file a claim without a lawyer. The contingency system in place in the United States may cause litigation to be pursued only when damages are severe enough to render likely the chance of high payments, leading to a selection of more severe injuries in the claims databases. A previous study has shown that the Dutch system is associated with relatively high rejection rates and low payments. In a study published by Griffen et al in 2007, 460 claims against general surgeons were reviewed to determine problematic aspects of surgical care. As in our study, failure in diagnosis or treatment and technical failures were the most common types of event. In addition, surgeons identified deficiencies in care more often before and after operations than in the intraoperative period. Most surgical safety checklists described so far have been focused on the operating room. The present study concurs with published findings that surgical errors are not only prevalent inside the operating room; only 38% of contributing factors occurred in the peroperative setting. Interventions to standardize surgical processes should target the entire pathway, from admission to discharge, to intercept errors both outside and inside the operating room. Items such as the presence of implants or the cessation of anticoagulants should not be left unchecked until the time out procedure just before surgery, when it may be too late. The preoperative part of SURPASS can intercept these and other incidents at an earlier time point that is, when there is still time to correct them. In addition, the checklist intercepts postoperative incidents, for example, related to instructions for postoperative care and medication at discharge. The SURPASS checklist covered over two-thirds of all contributing factors in the preoperative stage and almost 40% of factors in the postoperative stage. Because SURPASS is so comprehensive, its implementation requires more resources than the implementation of a more concise checklist. However, implementation is certainly feasible; the checklist has been successfully implemented both in academic hospitals and in regional teaching hospitals, and is being recommended as a best practice by the Dutch Inspectorate for Health Care. Once SURPASS has been implemented, the day-to-day use of the instrument does not demand much from its users. While the checklist as a whole may seem a little intimidating, the separate parts for each stage of the surgical pathway take little time to complete. There are a number of limitations to this study. Firstly, this was a retrospective study and the quality of the collected data was dependent on the quality of documentation in the medicolegal files. However, in most cases, extensive experts' assessments representing both patient and insurer were present in the file, ensuring sufficient information

available to categorize the incident and the contributing factors. Secondly, the denominator is unknown: we do not know how many operative procedures led to the 294 claims studied here. Thus, it was not possible to draw conclusions about the adverse event rate or use these numbers to compare different surgical disciplines. However, this study was not conducted to provide an incidence number for adverse events, but rather to perform an in-depth exploration of a broad selection of more severe surgical errors. Thirdly, although the hospitals insured by MediRisk represent a large proportion of all institutional health care in the Netherlands, university hospitals were not included in this study. It is possible that surgical incidents and their contributing factors are different in university hospitals. Finally, it is uncertain and only theoretical that all incidents of which contributing factors corresponded to SURPASS would indeed have been prevented had the checklist been used. Studies have shown that a checklist per se does not suffice to prevent harm from happening and that surgical safety procedures, even when performed correctly, do not prevent all preventable errors. The implementation of any surgical safety checklist should be accompanied by the development of a safety culture. The potential effect of the use of checklists and protocols is optimal in an environment where all care providers are aware of their own fallibility and acknowledge the value of checklists and protocols as a way of standardizing procedures. Strengths of this study include the large number of included centers (approximately 70% of all Dutch general hospitals) and the broad view that is provided of errors across all surgical disciplines and in all stages of the surgical pathway. It is the first study to provide an overview of all surgical malpractice claims in 1 country, and the first study to assess the proportion of surgical errors that might be prevented by the use of a surgical safety checklist. In conclusion, nearly one-third of all contributing factors in accepted surgical malpractice claims of patients that had undergone surgery, might have been intercepted by the SURPASS checklist. A considerable amount of damage, both physical and financial, is likely to be prevented by using SURPASS.

You might also like

- Healing Colon Liver and Pancreas Cancer - The Gerson WayDocument18 pagesHealing Colon Liver and Pancreas Cancer - The Gerson Waytzibellaris67% (3)

- The Battle Against Covid-19 Filipino American Healthcare Workers on the Frontlines of the Pandemic ResponseFrom EverandThe Battle Against Covid-19 Filipino American Healthcare Workers on the Frontlines of the Pandemic ResponseNo ratings yet

- PoliomyelitisDocument4 pagesPoliomyelitisGerard Adad Misa100% (1)

- Journal CHNDocument3 pagesJournal CHNNikki MasbangNo ratings yet

- CHN 2 JournalDocument2 pagesCHN 2 Journalinah krizia lagueNo ratings yet

- Ateneo de Davao University School of NursingDocument2 pagesAteneo de Davao University School of NursingXerxes DejitoNo ratings yet

- Assess Ability To Learn or Perform Desired Health-Related CareDocument6 pagesAssess Ability To Learn or Perform Desired Health-Related CareMarielle J GarciaNo ratings yet

- Health History and AssessmentDocument2 pagesHealth History and AssessmentRalph Justin Tongos100% (1)

- Chapter 1-3Document27 pagesChapter 1-3JellyAnnGomezNo ratings yet

- Impaired Physical MobilityDocument2 pagesImpaired Physical MobilityAl-Qadry NurNo ratings yet

- The Newborn Care: Fcnlxa - St. Luke's College of NursingDocument11 pagesThe Newborn Care: Fcnlxa - St. Luke's College of NursingFrancine LaxaNo ratings yet

- Sample PSADocument4 pagesSample PSAjudssalangsangNo ratings yet

- CC Er Reflection PaperDocument2 pagesCC Er Reflection Paperapi-545031607No ratings yet

- POA Sample-Head NursingDocument2 pagesPOA Sample-Head NursingGabriel FamatiganNo ratings yet

- NPI NCMH StephDocument12 pagesNPI NCMH StephAnonymous 2fUBWme6wNo ratings yet

- Jenny Anne Pimentel - ReflectionDocument1 pageJenny Anne Pimentel - ReflectionRona Bersamina AsuncionNo ratings yet

- BSN 215 Reflection Essay - LagoDocument2 pagesBSN 215 Reflection Essay - LagoAlliahkherzteen LagoNo ratings yet

- Head NurseDocument11 pagesHead Nursejannet20No ratings yet

- Tahbso ArticleDocument4 pagesTahbso ArticleAlianna Kristine OhNo ratings yet

- Dr. H. Achmad Fuadi, SPB-KBD, MkesDocument47 pagesDr. H. Achmad Fuadi, SPB-KBD, MkesytreiiaaNo ratings yet

- Sex Ed Personal Reflection 1Document2 pagesSex Ed Personal Reflection 1api-449509102No ratings yet

- Acute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture An International Perspective Part 2 PDFDocument15 pagesAcute Nursing Care of The Older Adult With Fragility Hip Fracture An International Perspective Part 2 PDFOktaNo ratings yet

- Jose Rizal Memorial State University: CommentsDocument4 pagesJose Rizal Memorial State University: CommentsJustine CagatanNo ratings yet

- Filipino Culture, Values, and Practices in Relation To Difficult Childbearing and ChildrearingDocument8 pagesFilipino Culture, Values, and Practices in Relation To Difficult Childbearing and ChildrearingRheeanne AmilasanNo ratings yet

- Standards of Nursing Practice Policies in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesStandards of Nursing Practice Policies in The PhilippinesJefferson UyNo ratings yet

- Ward Class TLGDocument1 pageWard Class TLGKashmire SapphireNo ratings yet

- Fdar (3 Days)Document2 pagesFdar (3 Days)giaNo ratings yet

- E. Nursing DiagnosisDocument2 pagesE. Nursing DiagnosisAle SandraNo ratings yet

- POA Head NursingDocument2 pagesPOA Head NursingNec EleazarNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument9 pagesCase Studyapi-267715207No ratings yet

- NCM 107-A # 2Document171 pagesNCM 107-A # 2Contessa GabrielNo ratings yet

- Journal ReadingDocument2 pagesJournal ReadingMark Ianne AngNo ratings yet

- ER Journal Summary - Effects of An Ethical Empowerment Program On Critical Care Nurses' Ethical Decision-MakingDocument1 pageER Journal Summary - Effects of An Ethical Empowerment Program On Critical Care Nurses' Ethical Decision-MakingWyen CabatbatNo ratings yet

- Angelica M.docx LFD 18Document2 pagesAngelica M.docx LFD 18Angelica Malacay RevilNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - HPVDocument6 pagesLesson Plan - HPVMonique MavronicolasNo ratings yet

- Western Mindanao State University College of Nursing Zamboanga CityDocument4 pagesWestern Mindanao State University College of Nursing Zamboanga CityEzra LambarteNo ratings yet

- Keeping The Peace: Conflict Management Strategies For Nurse ManagersDocument5 pagesKeeping The Peace: Conflict Management Strategies For Nurse ManagersCressabelle CaburnayNo ratings yet

- AnxietyDocument3 pagesAnxietyJenny Pearl Pasal50% (2)

- Journal Surg Ward BorjaDocument4 pagesJournal Surg Ward BorjaYana PotNo ratings yet

- COURSE OBJECTIVES or NursingDocument5 pagesCOURSE OBJECTIVES or NursingFil AquinoNo ratings yet

- Reflective Journal 1Document4 pagesReflective Journal 1api-365605511No ratings yet

- CC Chua, Prince Robert C. Reflection Paper 4ADocument1 pageCC Chua, Prince Robert C. Reflection Paper 4APrince Robert ChuaNo ratings yet

- Case Scenarios: Scenario 1Document2 pagesCase Scenarios: Scenario 1Kym RonquilloNo ratings yet

- RRLDocument2 pagesRRLbunso padillaNo ratings yet

- Job Application Letter For NurseDocument2 pagesJob Application Letter For Nursenur aisyahNo ratings yet

- A. Cultural Factors/ethnicity Such As Regard To Elders, Perception of HealthDocument3 pagesA. Cultural Factors/ethnicity Such As Regard To Elders, Perception of Healthlouie john abilaNo ratings yet

- SchedDocument1 pageSchedEdrick ValentinoNo ratings yet

- Service Quality of Hospital Outpatient Departments: Patients' PerspectiveDocument2 pagesService Quality of Hospital Outpatient Departments: Patients' Perspectivelouie john abilaNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking FHP WorksheetDocument17 pagesCritical Thinking FHP WorksheetfairwoodsNo ratings yet

- Obgyn ObjectivesDocument4 pagesObgyn ObjectiveshabbouraNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report For WardDocument4 pagesNarrative Report For WardAntonette PereyraNo ratings yet

- ICNP 2017-Catalogue Disaster NursingDocument27 pagesICNP 2017-Catalogue Disaster NursingHaniv Prasetya Adhi100% (1)

- Journal For MEdical WardDocument8 pagesJournal For MEdical WardValcrist BalderNo ratings yet

- PLAN OF ACTIVITIES 3 Days DRDocument5 pagesPLAN OF ACTIVITIES 3 Days DRKarl KiwisNo ratings yet

- Nursing Drug StudyDocument12 pagesNursing Drug StudyJoshkorro Geronimo100% (2)

- X. Nursing Care Plan: ObjectiveDocument6 pagesX. Nursing Care Plan: ObjectiveRenea Joy ArruejoNo ratings yet

- A Part 1 of Case Study by Angelene Tagle 09 08 2020Document6 pagesA Part 1 of Case Study by Angelene Tagle 09 08 2020pay tinapay100% (1)

- The Ride of Your Life: What I Learned about God, Love, and Adventure by Teaching My Son to Ride a BikeFrom EverandThe Ride of Your Life: What I Learned about God, Love, and Adventure by Teaching My Son to Ride a BikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Incidents During Out-of-Hospital Patient TransportationDocument9 pagesIncidents During Out-of-Hospital Patient TransportationKristy HolmesNo ratings yet

- The Incidence, Root-Causes, and Outcomes of Adverse Events in Surgical Units: Implication For Potential Prevention StrategiesDocument11 pagesThe Incidence, Root-Causes, and Outcomes of Adverse Events in Surgical Units: Implication For Potential Prevention StrategiesRihardy BayacsanNo ratings yet

- 01 Product Brochure NaviLink - English - DMS - 2610689 - 1Document14 pages01 Product Brochure NaviLink - English - DMS - 2610689 - 1UlrichNo ratings yet

- Case Report: SymptomsDocument4 pagesCase Report: Symptomsapi-339983807No ratings yet

- The Kapha DoshaDocument11 pagesThe Kapha DoshaNaseem AhmedNo ratings yet

- DiureticsDocument29 pagesDiureticsSaravanan RajagopalNo ratings yet

- Uterine Sub Mucosal Leiomyoma (Fibroid) - A Case ReportDocument5 pagesUterine Sub Mucosal Leiomyoma (Fibroid) - A Case ReportInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Nclex Med For NursesDocument24 pagesNclex Med For NursesSoleil Angeline Díaz77% (13)

- Depression: Depression Is Different From Sadness or Grief/BereavementDocument3 pagesDepression: Depression Is Different From Sadness or Grief/BereavementSalinaMaydinNo ratings yet

- ACG Clinical Guideline For The Diagnosis And.154Document30 pagesACG Clinical Guideline For The Diagnosis And.154PNo ratings yet

- pb520 PDFDocument142 pagespb520 PDFwisgeorgekwokNo ratings yet

- Down's Syndrome Pada KehamilanDocument35 pagesDown's Syndrome Pada KehamilanArga AdityaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For HemodyalysiDocument132 pagesGuidelines For HemodyalysipranshamNo ratings yet

- Leg ExercisesDocument7 pagesLeg ExercisesChoirun Nisa Nur AiniNo ratings yet

- Bray Etal.2009.Human Gene Map For Performance 2006 2007 Update Med Sci Sports Everc 2009Document39 pagesBray Etal.2009.Human Gene Map For Performance 2006 2007 Update Med Sci Sports Everc 2009Adam SimonNo ratings yet

- Counselling Stages and SkillsDocument40 pagesCounselling Stages and SkillsDavid Keenan50% (2)

- Irrigation of RCTDocument30 pagesIrrigation of RCTRafiur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Q&ADocument74 pagesQ&AfsolomonNo ratings yet

- Clientele and Audiences in CounselingDocument11 pagesClientele and Audiences in CounselingJoanna Mae Ramos100% (1)

- AppendicitisDocument25 pagesAppendicitisshahadelkanzi56No ratings yet

- Concepts of ResearchDocument19 pagesConcepts of ResearchJoaquin Feliciano100% (1)

- Full Medical Surgical Nursing Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems 10Th Edition Lewis Test Bank PDFDocument42 pagesFull Medical Surgical Nursing Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems 10Th Edition Lewis Test Bank PDFpage.yazzie410100% (18)

- Oral Iron Choices For Maternity v3.0 FINAL SCREENDocument2 pagesOral Iron Choices For Maternity v3.0 FINAL SCREENYusra AshrafNo ratings yet

- Aortic Valve StenosisDocument3 pagesAortic Valve StenosisgitanoviiaNo ratings yet

- Busquet - Cadenas Musculares (Laminas)Document377 pagesBusquet - Cadenas Musculares (Laminas)Carolina CalalvaNo ratings yet

- APA - DSM5 - Level 2 Anxiety Adult PDFDocument3 pagesAPA - DSM5 - Level 2 Anxiety Adult PDFDiana TodeaNo ratings yet

- Cancer Is Not A Disease-But A SymptomDocument2 pagesCancer Is Not A Disease-But A Symptomelenaconstantin1100% (1)

- Assessment and Management of Patients With Biliary DisordersDocument16 pagesAssessment and Management of Patients With Biliary DisordersJills JohnyNo ratings yet

- Dr. Marwah'S Test Series Whatsapp Number: 9873835363, 8447982490,9717143789Document15 pagesDr. Marwah'S Test Series Whatsapp Number: 9873835363, 8447982490,97171437891S@M1No ratings yet

- Biological Activity of Seeds of Wild BananaDocument8 pagesBiological Activity of Seeds of Wild BananaCassidy EnglishNo ratings yet

- Coek - Info - Hydrotherapy Principles and PracticeDocument1 pageCoek - Info - Hydrotherapy Principles and PracticeDiegoNo ratings yet