Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Avvai

Avvai

Uploaded by

shakri78Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

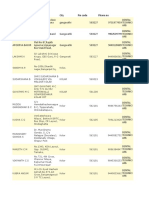

- Premchands Hindi Short Story Shatranj Ke KhiladiDocument13 pagesPremchands Hindi Short Story Shatranj Ke Khiladilastindiantango100% (1)

- TamilDocument85 pagesTamilSri VaishaliniNo ratings yet

- Games Ancient IndiaDocument15 pagesGames Ancient Indiashakri78No ratings yet

- RK InterviewDocument6 pagesRK Interviewshakri78100% (4)

- Indian Fables in Islamic ArtDocument12 pagesIndian Fables in Islamic Artshakri78No ratings yet

- Ravana TamilDocument9 pagesRavana Tamilshakri78No ratings yet

- (Pralaya) Translated by Richard A. Williams: The AnnihilationDocument5 pages(Pralaya) Translated by Richard A. Williams: The Annihilationshakri78No ratings yet

- Omar KhayyamDocument2 pagesOmar Khayyamshakri78No ratings yet

- Draupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic PerspectiveDocument9 pagesDraupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic Perspectiveshakri78No ratings yet

- AlvarsDocument5 pagesAlvarsshakri78No ratings yet

- Translation of Sanskrit Works in Akbar's CourtDocument8 pagesTranslation of Sanskrit Works in Akbar's Courtshakri78No ratings yet

- DuryodhanaDocument11 pagesDuryodhanashakri78No ratings yet

- YakshaganaDocument8 pagesYakshaganashakri78No ratings yet

- HanumanDocument6 pagesHanumanshakri78No ratings yet

- Myth and Reality of Mahabharata and RamayanaDocument5 pagesMyth and Reality of Mahabharata and Ramayanashakri78100% (2)

- The Raksasa Form of MarriageDocument11 pagesThe Raksasa Form of Marriageshakri78No ratings yet

- Oldest Record of Ramayana in A Chinese Buddhist WritingDocument5 pagesOldest Record of Ramayana in A Chinese Buddhist Writingshakri78No ratings yet

- Rome in The MahabharataDocument4 pagesRome in The Mahabharatashakri78No ratings yet

- Duryodhana & Queen of ShebaDocument2 pagesDuryodhana & Queen of Shebashakri78100% (1)

- List of Most Backward ClassesDocument6 pagesList of Most Backward ClassesthulasidharinfocrunchNo ratings yet

- TN-Tamil Nadu: Chennai South East - MandaveliDocument3 pagesTN-Tamil Nadu: Chennai South East - MandaveliKirubha VenkateshNo ratings yet

- Irrigation & CAD DepartmentDocument2 pagesIrrigation & CAD DepartmentA. D. PrasadNo ratings yet

- Ifsc 1Document552 pagesIfsc 1salboniNo ratings yet

- The Deccan Kingdoms Medieval History of India Notes For UPSCDocument7 pagesThe Deccan Kingdoms Medieval History of India Notes For UPSCravi kumarNo ratings yet

- City Travel Briefing ChennaiDocument30 pagesCity Travel Briefing Chennaipiyush saxenaNo ratings yet

- SudharshanDocument5 pagesSudharshanSihina VijithayaNo ratings yet

- Aso GRLDocument1,166 pagesAso GRLvenkat annabhimojuNo ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu Government Gazette: Part II-Section 1Document2 pagesTamil Nadu Government Gazette: Part II-Section 1rajendranrajendranNo ratings yet

- The Voyage of Vellinezhi: Economic and Political Weekly March 2019Document3 pagesThe Voyage of Vellinezhi: Economic and Political Weekly March 2019Geosha AnshilNo ratings yet

- Power Map of Southern Region: Hyderabad DetailsDocument1 pagePower Map of Southern Region: Hyderabad Detailsgaurang1111No ratings yet

- Districtwise List of Villages Above 2000-27.05.10Document154 pagesDistrictwise List of Villages Above 2000-27.05.10samynathanNo ratings yet

- Nandikeshwara Ashtottara Shata Namavali Tamil PDF File1707Document10 pagesNandikeshwara Ashtottara Shata Namavali Tamil PDF File1707harikukaNo ratings yet

- Pure Tamil Baby Names For Boys - Pure Tamil Baby NamesDocument5 pagesPure Tamil Baby Names For Boys - Pure Tamil Baby NamesRoyal Dhiva100% (1)

- The Chola HistoryDocument1 pageThe Chola Historydge4scribNo ratings yet

- Tamil Society EnglishDocument4 pagesTamil Society Englishkeerthigopalakrishnan18No ratings yet

- Tamilnadu by SamreenDocument9 pagesTamilnadu by SamreengulamrasoolNo ratings yet

- Government of Telangana Irrigation & Cad DepartmentDocument2 pagesGovernment of Telangana Irrigation & Cad DepartmentQC&ISD1 LMD COLONYNo ratings yet

- All Govt Exam Study Materials Special Names of Indian Cities MyKalviDocument5 pagesAll Govt Exam Study Materials Special Names of Indian Cities MyKalvimykalviNo ratings yet

- S. No. State College Name Principal Name Principal E-Mail: Bhaskar RamamurthDocument4 pagesS. No. State College Name Principal Name Principal E-Mail: Bhaskar Ramamurthmanish balajiNo ratings yet

- Gangasoftalkad 035344 MBPDocument345 pagesGangasoftalkad 035344 MBPHistoria IndicaNo ratings yet

- English To Tamil DictionaryDocument4 pagesEnglish To Tamil DictionaryVidhya Raghavan100% (2)

- Dentapdf-Free1 1-524 1-200Document200 pagesDentapdf-Free1 1-524 1-200Shivam SNo ratings yet

- Admission 2014 NewDocument124 pagesAdmission 2014 Newdev2945No ratings yet

- Manakula Vinayagar PDFDocument21 pagesManakula Vinayagar PDFArunsugumarNo ratings yet

- Vaikhunta Perumal TempleDocument9 pagesVaikhunta Perumal TempleRICHA KUMARINo ratings yet

- University of Kerala: Reporting Time: 08.00 Am To 10.00 AmDocument4 pagesUniversity of Kerala: Reporting Time: 08.00 Am To 10.00 AmBalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- State Wise List of Registered FPOs Details Under Central Sector Scheme For Formation and Promotion of 10,000 FPOs by SFAC As On 31-12-2023Document200 pagesState Wise List of Registered FPOs Details Under Central Sector Scheme For Formation and Promotion of 10,000 FPOs by SFAC As On 31-12-2023rahul ojhhaNo ratings yet

- Incredible India (South) SandeshDocument9 pagesIncredible India (South) SandeshChetan Ganesh RautNo ratings yet

Avvai

Avvai

Uploaded by

shakri78Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Avvai

Avvai

Uploaded by

shakri78Copyright:

Available Formats

The Avvai of the Sangam Anthologies

By M. S. H. THOMPSON

T HERE is perhaps no writer held in greater esteem in the Tamil country

than the poetess Avvai or Auvai, as her name is given in the old commentaries and in a poem of the Sangam age.' The editor of a selection of poems from those traditionally ascribed to Avvai says that the poetess was an incarnation of the goddess of learning, while the writer of the foreword to his book says the joy of her presence is with us in the world to-day. An editor and annotator of a philosophical work ascribed to her writes in much the same strain, remarking that the work in question is the fruit of the penance of the whole Tamil country. This is the Avvai of Tamil legend, as Anavarata Vinayakam Pillai shows in his able monograph on the poetess, and it is the Avvai to whom the early writers on Tamil literature refer. For example, Henry Bower, who wrote: " She sang as sweetly as Sappho; yet not of love, but of virtue." Also Simon Casie Chitty in his Indian Plutarch, though he says his facts were " carefully collected and scrupulously detached from fictitious and ornamental additions ". The following observations of Taylor on the Adichadi Vej.ba may show an acquaintance with Sangam religion, but there can be little doubt that the poet he had in mind was the legendary Avvai:"The work, it is said, was entitled Niti Chol by the author = a word on morals, a discourse on rectitude; but some later writer prefixed stanzas of invocation addressed to Siva or Ganesa, using the words ddi chudi at the beginning of his panegyric, whence the book has improperly acquired its popular title." The poet whom the younger Caldwell translated so skilfully was again the legendary Avvai. Scholars are now generally agreed that the only Avvai about whom anything at all reliable is known is the Avvai of the Sangam Anthologies, fifty-nine of whose poems appear in four of the earliest of the anthologies, nearly half of them dealing with love. The discovery of this Avvai has been made possible by the printing of the Sangam Anthologies, which until some fifty years ago were known only in extract, as Dr. Saminatha Iyer tells us in his University lectures delivered in Madras in 1927. The best edited of the anthologies is Purandnaru, in which there are thirty-three poems said to have been composed by Avvai. Twenty-four of them appear with an old commentary, and the editor has provided cross references and illustrative parallel passages from other

1 Cirupan&rruppadai, line 101. In stanza 214 of Tirukkovaiyar we have auvai and in stanza 396 avvai. Chudanamzi Neganidugives eight other synonyms for " mother " besides avvai. The name Avvai was titular, the real name of the poetess not being known.

400

M. S. H. THOMPSON-

classics that are very helpful. It is from this work that most citations occur in essays on Avvai and recent works on Tamil literature, like Duraisami Pillai's account of Tamil literature of the Sangam Age. Citations rarely, if ever, occur from the Agandnuiru,in which there is a commentary consisting of brief but valuable notes on but ninety of the four hundred poems included in the anthology. The remaining two anthologies, Narrinai and Kuruntogai, have been edited with modern commentaries, of which that by Narayanasami Iyer on Narrinai is the abler of the two, though not free from faults, as Venkatarajulu Reddiyar has shown in his monograph on Kapilar. In his long introduction to Kuzruntogai the editor has described the difficulties he was confronted with, and his laborious work recalls Caldwell's remark regarding Tamil pandits : " Native pandits have never been surpassed in patient labour or in an accurate knowledge of details." In the editing of Sangam works Dr. Saminatha Iyer provided as accurate a text as possible with such commentary as was available; he added little of his own by way of explanation. In his introduction to Ainkurunuru he tells us with characteristic modesty that the skill of the unknown commentator put him off giving any explanations of his own, so that whenever he provided glossaries they mostly reproduced what had already appeared in the commentary. This is surely to be deplored, because he was better able than anyone else to give the kind of help one needs in reading the Sangam works, in which " many verbal and grammatical enigmas have been most faithfully preserved and handed down by successive generations of scholars with little or no attempt at their elucidation ", as Sivaraja Pillai says. The Tamil Lexicon issued by the Madras University was meant to help with the study of the Tamil classics; but anyone who turns to it in his perplexities while grappling with the text of a Sangam work is more than likely to be disappointed. The systematic editing of the earlier Tamil classics has already been urged, and it is in Madras where such work could be best carried out, preferably by the University.

* * *

"Prosper, O land ", sings our poetess. " Where good men dwell, there the land is good, whether countryside or forest, valley or plateau." She was a great traveller, and seems to have travelled on foot all over South India. One of the glimpses we obtain from her poems is of her coming down a mountain path with her companions bearing their goods and chattels suspended from poles borne on their shoulders, as travellers on foot do at the present day. She was sure of a welcome wherever she went. " The prattle of his little son is music in the ears of his father, and so, with all its imperfections, is my song in your ears ", she tells her patron. A dancer and singer by profession, she made the most of her opportunities. In a poem addressed to a doorkeeper she refers to her class as "we who sow an illuminating word in the ear of the generous and by sheer strength of will draw forth a gift befitting our status ", adding: "An empty world would this be were the cultured and the famous to pass

THE AVVAI OF THE SANGAM ANTHOLOGIES

401

out of it." The sons of the wood-workers find all they need in the forest. " So we too ", she concludes, " find rice wherever we go." Most of her poems in PuranJnitru are in praise of the chieftain Nedumananji, whose lands are thought to have been in Mysore round about Kolar. How trusted a friend she was is shown by the fact that she undertook an embassy on his behalf to Thondaiman. As recorded in one of her poems, she subtly praised her patron by seeming to belittle his achievements. Here is the outline of a poem in fiercer vein :" Seeing your elephant charge with short, blunted tusks, as the doors of the fort flew to pieces, seeing your charger gallop with hoofs bespattered with blood from trampling on the fallen foe, they returned their blood-stained arrows to their sheaths, as they saw your warriors advancing sword in hand." In much the same strain is the following poem, though it ends on a tender note :" In his hand the spear, on his legs anklets, the sweat standing on his brow, the wound on his neck unhealed, his garland the garland of palmyra interwoven with vetchi and vengai, his black hair coiled in a shiny mass, strong as an elephant that has fought and slain the striped tiger, none of his enemies have survived of those who provoked him to anger. The eyes that once glared in fury have not turned red as they have looked on the little son." The love lyrics strike a different note. Here we meet the love-lorn maiden and the anxious suitor, and the scene shifts from the plains to the hills. Now the sun is sinking behind a range of hills aglow with the rays of the setting sun, and the shadows lengthen in the grove where, with bowed head, a maiden hears the sound of bells grow fainter as her lord speeds away in his chariot. Now maidens bedecked with flowers crowd round the lord of the land, and all is noise and confusion, while a few paces away the otter sleeps in the pond. We hear the beat of drums and the blare of conches. Then away we go to the hills. Here night has descended, and with it the rain. The speckled hood of the snake quivers in the storm. Then day dawns, and trees resplendent with flowers shine like the neck of the peacock, while mountain torrents tear at the roots of the trees growing on their banks. Like a beam of light a maiden steals through the overhanging branches, as the mists rise up from the valley below. Up the steep path mounts the chariot of her lord and master, who is afraid that the herdsman's horn, loud as the roll of thunder, has struck terror into her heart. Lastly, the lament over the dead chieftain, whom Avvai delighted in praising. " Let the flames leap high into the heavens ", she sings; "never will fade the fame of him as bright as the sun, with white umbrella as bright as the moon." Henceforth it will seem to her as though there were neither morning nor evening.

402

THE AVVAI OF THE SANGAM ANTHOLOGIES BIBLIOGRAPHY

Auvai Arumtamil. By A. Subramanya Bharathi. Madras, 1921. Auvaikkural. By E. Sundaramanicka Yogishvarar. Madras, 1926. Avvaiyar. By S. Anavarata Vinayakam Pillai. Madras, 1919. Calcutta Review, xxv, 1855, pp. 158-196. Art. vii: The Tamil Language and Literature. (By Henry Bower, as Murdoch states; also R. S. Swinton in An Indian Tale or Two, Blackheath, 1898.) 5. The Tamil Plutarch. A Summary Account of the Lives of Southern India and Ceylon from the Earliest to the Present Times, with Select Specimens of Their Compositions. By Simon Casie Chitty. Jaffna, 1859. 6. A Catalogue Raisonnee of Oriental iMauscripts in the Library of the (Late) College, Fort Saint George.[Now in charge of the Board of Examiners. By the Rev. William Taylor. Vol. I, 1857. Vol. II, 1860. Vol. III, 1862. 7. Sangam Tamil and Latter-day Tamil. Lectures delivered by Dr. Saminatha Iyer under the auspices of the Madras University between 7th November and 21st December, 1927. Madras, 1929. 8. The Text and Commentary of Purananuru, One of the Eight Anthologies. Edited by V. Saminatha Iyer. 3rd ed. Madras, 1935. 9. Tamil Literature: the Sangam Age. By G. C. Duraisami Pillai. Association Press, Calcutta, 1923. 10. Agandanru, One of the Eight Anthologies. The Text and the Old Commentary. Edited by Raghava Iyengar. Madras, 1918. 11. Narrinai, One of the Eight Anthologies. Edited with Commentary by A. Narayanasami Iyer. Madras, 1914. 12. Kuruntogai, One of the Eight Anthologies. Edited with New Commentary by T. T. Chowri Perumala Rangan. 1915. 13. Kapilar. (Madras University Tamil Series, No. 5.) By Vidvan V. Venkatarajulu Reddiyar. 1936. 14. A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages. By R. Caldwell. 3rd ed. Revised by Wyatt and Ramakrishna Pillai. London, 1913. 15. Aingkurunuru. Edited with the Old Commentary by V. Saminatha Iyer. Madras, 1903. 16. The Chronologyof the Early Tamils. By K. N. Sivaraja Pillai. University of Madras, Madras, 1932. 17. Tamil Lexicon, completed in 1936. 18. Indian Antiquary, i, pp. 197-201. (R. C. Caldwell's articles on Tamil popular poetry.) 19. Indian Antiquary, lix, p. 189. (C. S. Srinivasachari's review of the Tamil Lexicon.) 20. Indian Antiquary, Ix, p. 140. (F. J. Richards' review of Studies in Tamil Literature and History, by Ramachandra Dikshitar.) 21. Ancient Famous Tamil Poets, pp. 136-174. By A. Karmega Kone. Madura, 1925. 22. The History of Auvaiyar. (Wealth of Learning Series, No. 11. General Editor: V. G. Suryanarayana Sastri.) By C. Subramanyachariar. Madras, 1902. 23. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, xvii (New Series), 1885. Art. viii, by G. U. Pope, pp. 179-81.

1. 2. 3. 4.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

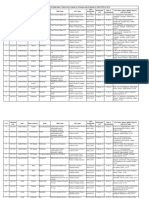

- Premchands Hindi Short Story Shatranj Ke KhiladiDocument13 pagesPremchands Hindi Short Story Shatranj Ke Khiladilastindiantango100% (1)

- TamilDocument85 pagesTamilSri VaishaliniNo ratings yet

- Games Ancient IndiaDocument15 pagesGames Ancient Indiashakri78No ratings yet

- RK InterviewDocument6 pagesRK Interviewshakri78100% (4)

- Indian Fables in Islamic ArtDocument12 pagesIndian Fables in Islamic Artshakri78No ratings yet

- Ravana TamilDocument9 pagesRavana Tamilshakri78No ratings yet

- (Pralaya) Translated by Richard A. Williams: The AnnihilationDocument5 pages(Pralaya) Translated by Richard A. Williams: The Annihilationshakri78No ratings yet

- Omar KhayyamDocument2 pagesOmar Khayyamshakri78No ratings yet

- Draupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic PerspectiveDocument9 pagesDraupadi On The Walls of Troy: Iliad 3 From An Indic Perspectiveshakri78No ratings yet

- AlvarsDocument5 pagesAlvarsshakri78No ratings yet

- Translation of Sanskrit Works in Akbar's CourtDocument8 pagesTranslation of Sanskrit Works in Akbar's Courtshakri78No ratings yet

- DuryodhanaDocument11 pagesDuryodhanashakri78No ratings yet

- YakshaganaDocument8 pagesYakshaganashakri78No ratings yet

- HanumanDocument6 pagesHanumanshakri78No ratings yet

- Myth and Reality of Mahabharata and RamayanaDocument5 pagesMyth and Reality of Mahabharata and Ramayanashakri78100% (2)

- The Raksasa Form of MarriageDocument11 pagesThe Raksasa Form of Marriageshakri78No ratings yet

- Oldest Record of Ramayana in A Chinese Buddhist WritingDocument5 pagesOldest Record of Ramayana in A Chinese Buddhist Writingshakri78No ratings yet

- Rome in The MahabharataDocument4 pagesRome in The Mahabharatashakri78No ratings yet

- Duryodhana & Queen of ShebaDocument2 pagesDuryodhana & Queen of Shebashakri78100% (1)

- List of Most Backward ClassesDocument6 pagesList of Most Backward ClassesthulasidharinfocrunchNo ratings yet

- TN-Tamil Nadu: Chennai South East - MandaveliDocument3 pagesTN-Tamil Nadu: Chennai South East - MandaveliKirubha VenkateshNo ratings yet

- Irrigation & CAD DepartmentDocument2 pagesIrrigation & CAD DepartmentA. D. PrasadNo ratings yet

- Ifsc 1Document552 pagesIfsc 1salboniNo ratings yet

- The Deccan Kingdoms Medieval History of India Notes For UPSCDocument7 pagesThe Deccan Kingdoms Medieval History of India Notes For UPSCravi kumarNo ratings yet

- City Travel Briefing ChennaiDocument30 pagesCity Travel Briefing Chennaipiyush saxenaNo ratings yet

- SudharshanDocument5 pagesSudharshanSihina VijithayaNo ratings yet

- Aso GRLDocument1,166 pagesAso GRLvenkat annabhimojuNo ratings yet

- Tamil Nadu Government Gazette: Part II-Section 1Document2 pagesTamil Nadu Government Gazette: Part II-Section 1rajendranrajendranNo ratings yet

- The Voyage of Vellinezhi: Economic and Political Weekly March 2019Document3 pagesThe Voyage of Vellinezhi: Economic and Political Weekly March 2019Geosha AnshilNo ratings yet

- Power Map of Southern Region: Hyderabad DetailsDocument1 pagePower Map of Southern Region: Hyderabad Detailsgaurang1111No ratings yet

- Districtwise List of Villages Above 2000-27.05.10Document154 pagesDistrictwise List of Villages Above 2000-27.05.10samynathanNo ratings yet

- Nandikeshwara Ashtottara Shata Namavali Tamil PDF File1707Document10 pagesNandikeshwara Ashtottara Shata Namavali Tamil PDF File1707harikukaNo ratings yet

- Pure Tamil Baby Names For Boys - Pure Tamil Baby NamesDocument5 pagesPure Tamil Baby Names For Boys - Pure Tamil Baby NamesRoyal Dhiva100% (1)

- The Chola HistoryDocument1 pageThe Chola Historydge4scribNo ratings yet

- Tamil Society EnglishDocument4 pagesTamil Society Englishkeerthigopalakrishnan18No ratings yet

- Tamilnadu by SamreenDocument9 pagesTamilnadu by SamreengulamrasoolNo ratings yet

- Government of Telangana Irrigation & Cad DepartmentDocument2 pagesGovernment of Telangana Irrigation & Cad DepartmentQC&ISD1 LMD COLONYNo ratings yet

- All Govt Exam Study Materials Special Names of Indian Cities MyKalviDocument5 pagesAll Govt Exam Study Materials Special Names of Indian Cities MyKalvimykalviNo ratings yet

- S. No. State College Name Principal Name Principal E-Mail: Bhaskar RamamurthDocument4 pagesS. No. State College Name Principal Name Principal E-Mail: Bhaskar Ramamurthmanish balajiNo ratings yet

- Gangasoftalkad 035344 MBPDocument345 pagesGangasoftalkad 035344 MBPHistoria IndicaNo ratings yet

- English To Tamil DictionaryDocument4 pagesEnglish To Tamil DictionaryVidhya Raghavan100% (2)

- Dentapdf-Free1 1-524 1-200Document200 pagesDentapdf-Free1 1-524 1-200Shivam SNo ratings yet

- Admission 2014 NewDocument124 pagesAdmission 2014 Newdev2945No ratings yet

- Manakula Vinayagar PDFDocument21 pagesManakula Vinayagar PDFArunsugumarNo ratings yet

- Vaikhunta Perumal TempleDocument9 pagesVaikhunta Perumal TempleRICHA KUMARINo ratings yet

- University of Kerala: Reporting Time: 08.00 Am To 10.00 AmDocument4 pagesUniversity of Kerala: Reporting Time: 08.00 Am To 10.00 AmBalakrishnanNo ratings yet

- State Wise List of Registered FPOs Details Under Central Sector Scheme For Formation and Promotion of 10,000 FPOs by SFAC As On 31-12-2023Document200 pagesState Wise List of Registered FPOs Details Under Central Sector Scheme For Formation and Promotion of 10,000 FPOs by SFAC As On 31-12-2023rahul ojhhaNo ratings yet

- Incredible India (South) SandeshDocument9 pagesIncredible India (South) SandeshChetan Ganesh RautNo ratings yet