Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gombrich

Gombrich

Uploaded by

Gaylord FAOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gombrich

Gombrich

Uploaded by

Gaylord FACopyright:

Available Formats

The Wit of Saul Steinberg Author(s): E. H. Gombrich Reviewed work(s): Source: Art Journal, Vol. 43, No.

4, The Issue of Caricature (Winter, 1983), pp. 377-380 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/776737 . Accessed: 05/01/2012 06:27

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

College Art Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Art Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

The

Wit

of

Saul

Steinberg

to'-

By E.H. Gombrich

f

--

c( ,~/

,...:--:

i -.

THE NEWWORLD/

Fig. 1 Steinberg, TheNew World, dedication.

Steinberg wrote and for Tme his volumedrewNewme when he sent Fig. 2 Steinberg,TheNew World. The

World (Fig. 1) may not seem to fit into a series of articles devoted to the themeof caricature. it is Yet not only personal vanity which prompts me to take it as a starting pointfor this brief discussion of the artist's wit. Look at the drawing more carefully and you will see that it does not "work out." Whatappears at first sight as a sequence of stacked oblongs, superimposedor stuck into one another, turns out to be so cunningly devised that it would be impossible to constructsuch a configurationin real space. It so happensthatI owe this generousgift to the words which I devoted to the artistin my book on Art and Illusion: "There is perhaps no artist alive who knows more about the philosophy of representation." The tribute, incorporated an article by in Harold Rosenberg, was quoted to my delight on the dust cover of Steinberg'snext book; hence his present, which illustrates and confirmsmy words with thateconomy of means which is one of the hallmarks of Steinberg's art. It has often been said that the real or dominant subject matter of twentiethcentury art is art itself. If that is the case, to Steinberg'scontribution the subjectmust never be underrated.Without going over the ground again which I covered in my book I may point out that the drawing which I chose here as my startingpoint offers a more illuminatingcommenton the essence of Cubism than many lengthy books about the Cubist conception of "space" and its alleged relation to Einstein's theoryof relativity. Rosenberg quoted Steinberg's remark: "What I draw is drawing, [and] drawing derives from drawing. My line wants to remind constantlythat it is madeof ink."'I The reminderis made explicit on another page of The New World (Fig. 2), which shows the artist'spleasurein catchingus in the traps of his visual contradictions.It would be otiose to pointthemout in detail. Winter1983 377

he dedication which Saul

Fig. 3 Steinberg,ThePassport, 1954. Indeed, one of the problems in writing about Steinberg's wit is precisely the fact thathis drawingsmaketheirpointso much betterthanwordsever could. Whatmaybe said, however, aboutthe artist'sremarkis thateven thoughhe remindsus constantly, he never fully convinces us. Try as we may, what we see is notjust ink. The little man who cancels himself (Fig. 3) remains pathetic and intriguing. The drawing proves, if proof were needed, that our reactionto pictorialrepresentation quite is independentof the degreesof realism.It is a functionof ourunderstanding it takes and an enormous effort to inhibit our understandingand only see ink. Thereis indeeda parallelproblemin our reaction to language. If we could easily hear the words "all Cretansare liars" as just a string of noises (as we would if we heard them in a foreign language), the whichariseswhen paradoxof self-reference a Cretanspeaksthemwouldnot troubleus. What must be one of the earliest of Steinberg's humorousdrawingsto be included in one of his volumes neatly illustrates the play between "ink" and meaning in a joke that still relies on a caption (Fig. 4). Whatstartsas a graphturnsinto a real force smashing through the floor. There is as yet no real paradoxhere, no more than in the metaphorsof language which we do not take literally,as when we say that prices "rocket" or "slump." In self-reference we cannotinterpret without running up against a contradiction,and contradictionsareone of the manyhumorous devices Steinberguses to producethe shock of laughter,as when we look at the mysterioustable which is also the rim of a bathtub visualjoke worth (Fig. 5)---another disquisitionsaboutthe readmany lengthy ing of images. This process of reading is examinedin many of the drawings in which the artist explores the very limits of graphicsigns. He shows us how the simplestgeometrical configurations will suddenly resemble a

Fig. 4 Steinberg,All in Line.

Fig. 5 Steinberg,TheInspector. humanhead and exhibit a definiteindividuality and expression, as is the case with the odious pairwho appearto arriveas the guests of a party(Fig. 6). Needless to say, these explorationsof what I have called "the philosophyof representation" have also taken him much furtherafield. In some of his wittiestdrawings we see him commenting on a timehonored problem of criticism, that of the properrelationbetween form andcontent. The general heading under which this question used to be discussed since classical antiquity is that of the decorum, the fitting of the rightwordor style to the right subject matter,memorablysummedup (as far as poetry is concerned) in Alexander Pope's "Essay on Criticism": 'Tis not enough no harshnessgives offence, The sound must seem an echo to the sense: Soft is the strainwhen Zephyrgently blows, And the smooth streamin smoother numbersflows: But when loud surgeslashthe sounding shore,

378

ArtJournal

Fig. 6 Steinberg, TheNew World. The hoarse, rough verse should like the torrentroar. When Ajax strives some rock's vast weight to throw The line, too, labours,andthe words move slow.

Fig. 7 Steinberg, "Family," ThePassport, 1954.

As I have indicatedin the last chapterof Art and Illusion, attemptshave not been wanting in the past to applythis doctrineto the visual arts, but we had to wait for a Steinbergto applyit withutmostsimplicity. In many of his drawingsit is againthe line or the graphic medium which seems "an echo to the sense." His "Family" (Fig. 7) shows us the father firmly modeled, the mother with all undulating lines, the grandmother but fading away between hesitantpen strokes, and, of course, the child drawnin the style of children's scribbles. From here it is but one step to the representation of what are called our synaesthetic reactions, the depictionof one sense modality by another.The soundsof "Giuseppe Verdi" floatingthroughthe window (Fig. 8) do not leave us in doubt thatit is early Verdi. As this example shows, there is no dis7-. tinction in Steinberg's manipulation of "ink" between representation writing. and He can incorporateall the means of visual communication in his images. To quote his words once more: "I appeal to the complicity of my reader who will transform the line into meaning by using our common backgroundof culture, history, in poetry. Contemporaneity this sense is a complicity. "2 The conventionaldevice of a "balloon" surroundingwords or thoughtsis used to delightfulpurposein the imageof the rocking chairdreamingof being a rockinghorse (Fig. 9). The questionmark,as so often in real life, takes off and pursues us, the Fig. 8 Steinberg,TheNew World.

(Ai

L i;

Winter1983

379

Fig. 10 Steinberg, TheNew World. tainer, hardlyworthyof the attentionof the superior persons who study and analyze the creationsof serious "artists." Unless I am much mistaken,Steinberg's work is not referred to in the standard books on twentieth-centuryart, nor does he seem to figure in the survey courses explaining and tabulating the various "isms" said to makeup the modem movement. Whetherhe resentsthis comparative lack of attentionaccordedhim in the curriculum of art historians I do not know. But it seems to me thatone of his drawings (Fig. 12) offers the best commenton this situation: A solemn procession of stereotyped graybeardsis marchingpast a dull official building aptly inscribed as "The National Academy of the Avant-Garde." Fig. 11 Steinberg, TheInspector. Maybe they will all be forgotten when withgratitude Steinbergis still remembered and pleasure.

Fig. 9 Steinberg, TheNew World.

At

conventional lines indicating its bounces Notes E.H. GombrichwasformerlyDirectorof (Fig. 10). But Steinberg has also used 1 HaroldRosenberg,Saul Instituteand Professor of the Steinberg,New the Warburg script and words more insistently, indeed History of the Classical Traditionat YorkandLondon,1978,p. 19. morephilosophically,in suchcompositions the UniversityofLondon.Amonghis many ibid.,p. 22. as Figure 11, where he contraststhe firm 2 Quoted publications are Art and Illusion, foundation of the words I AM with the Meditationson a HobbyHorse,The Sense ramshackleinstabilityof I HAVE and the of Order,and, most recently, The Image radianttriumphof I DO. and The Eye: FurtherStudiesin the Everybody will have his own favorites Psychology of PictorialRepresentation. among Steinberg's ingenious visualizations, such as his mappingof time where we are shown the frontier of March and April which is just being crossed by his THENATIONAL ACADE~y favoritecat, or his parodistic OF THE AVANT-6ARPDE manipulations of patriotic symbolism in his GrandTab-70 leaux of political rhetoric. Nor should we forget thathe is not merelya masterof line but can use all the means of trompel'oeil / in his spoof picturepostcardsor his meticulous engineeringdrawings. El ' E theendof Plato'sSymposium, when - E 11 1 / the rest of the company had either I--u fallen asleep or gone home, we hear that 0 0 0 0', 0 Socrates was still arguing with Agathon and Aristophanes. Socrates was driving them to the admission that the same man could have theknowledgerequired writfor ing comedy and tragedy, at which Aristophanes began to nod and then Agathon, while Socrates walked off, apparently / V 1 happy in the knowledge that he had won the argument. Ijz2,4 But has he? The idea persists that the comedian or caricaturistis a mere enter- Fig. 12 Steinberg, TheInspector. 380 Art Journal

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The BFG - An Integrated English UnitDocument7 pagesThe BFG - An Integrated English Unitapi-208000806No ratings yet

- Top Notch Fundamentals Unit 14 AssessmentDocument7 pagesTop Notch Fundamentals Unit 14 AssessmentNN67% (3)

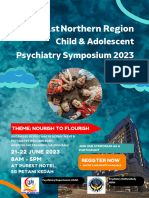

- Northen Region CAMHS SymposiumDocument7 pagesNorthen Region CAMHS Symposiumsiti zaharahgustiNo ratings yet

- Supervision Diary TemplateDocument11 pagesSupervision Diary TemplateVenusNo ratings yet

- Advocacy SpeechDocument1 pageAdvocacy SpeechCharlie PuthNo ratings yet

- Latte & 6 StepsDocument5 pagesLatte & 6 StepsHtin Lin KyawNo ratings yet

- APPEALSDocument4 pagesAPPEALSManiza KhanNo ratings yet

- Cleric - Madness Divine DomainDocument1 pageCleric - Madness Divine DomainRomuald ARTILLACNo ratings yet

- Towers of Hanoi and London: Reliability and Validity of Two Executive Function TasksDocument9 pagesTowers of Hanoi and London: Reliability and Validity of Two Executive Function TasksABRAHAM PHİLİP VANMANNEKESNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Psychology Final ExamDocument10 pagesAdolescent Psychology Final ExamMoises MartinezNo ratings yet

- Activity 3 - Deputado ManingDocument2 pagesActivity 3 - Deputado Maningt swiftNo ratings yet

- How To Negotiate With French Business Partners 5 Tips For Management and Negotiation in INTERCULTURAL DiscussionsDocument13 pagesHow To Negotiate With French Business Partners 5 Tips For Management and Negotiation in INTERCULTURAL Discussions.No ratings yet

- Case Study On Implicit Bias by Nurses.Document7 pagesCase Study On Implicit Bias by Nurses.Raphael NdambukiNo ratings yet

- False Hydra Module 5eDocument8 pagesFalse Hydra Module 5eДаниил ЕгоровNo ratings yet

- TRUGO ChiSquareDocument8 pagesTRUGO ChiSquaremoreNo ratings yet

- Chapter 09 Peers, Romantic Relationships, and Life Styles - Version1Document77 pagesChapter 09 Peers, Romantic Relationships, and Life Styles - Version1SaimaNo ratings yet

- Akshay ResumeDocument2 pagesAkshay Resumeakshayrao823No ratings yet

- How Has GSELF Helped MeDocument2 pagesHow Has GSELF Helped MeDon J AsuncionNo ratings yet

- Extended EssayDocument17 pagesExtended EssaySaurabh JainNo ratings yet

- Jerry Zara Psy FinalDocument7 pagesJerry Zara Psy FinalNIMRAH RAISNo ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan For ENGLISH 10 Week 2-7, Quarter 1 Day & Time Learning Area Learning Competency Learning Tasks Mode of DeliveryDocument5 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan For ENGLISH 10 Week 2-7, Quarter 1 Day & Time Learning Area Learning Competency Learning Tasks Mode of DeliveryRia-Flor ValdozNo ratings yet

- COT - Filipino 3 Q1 W8 Paggamit Sa Usapan NG Mga Salitang Pamalit Sa Ngalan NG TaoDocument2 pagesCOT - Filipino 3 Q1 W8 Paggamit Sa Usapan NG Mga Salitang Pamalit Sa Ngalan NG TaoNatalia TorresNo ratings yet

- PMI Pulse of The Profession 2023 ReportDocument22 pagesPMI Pulse of The Profession 2023 ReportThauan GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Class 4 Urdu Reinforcement W Sheet 2 TafheemDocument5 pagesClass 4 Urdu Reinforcement W Sheet 2 TafheemAsad KhanNo ratings yet

- Organizational Structure Policy of BataDocument6 pagesOrganizational Structure Policy of BataSadia SadneenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6-7-8Document11 pagesChapter 6-7-8The WolfNo ratings yet

- Part III LESSON 3 Taking Charge of One's HealthDocument12 pagesPart III LESSON 3 Taking Charge of One's HealthMelvin Pogi138No ratings yet

- Affective Encounters. Rethinking Embodiement in Feminist Media Studies - Koivunen y PaasonenDocument296 pagesAffective Encounters. Rethinking Embodiement in Feminist Media Studies - Koivunen y PaasonenAlejandro Varas AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- A Cognitive Process of WritingDocument3 pagesA Cognitive Process of WritingNatisolangeCorrea67% (3)

- Indicators For Factors 1 To 4 of The DepEd Evaluation Rating SheetDocument4 pagesIndicators For Factors 1 To 4 of The DepEd Evaluation Rating SheetJoselito Requirme AguaNo ratings yet