Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trans Fatty Acids in Dietary Fats and Oils From 14 European: Countries: The TRANSFAIR Study

Trans Fatty Acids in Dietary Fats and Oils From 14 European: Countries: The TRANSFAIR Study

Uploaded by

pfradinho4993Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trans Fatty Acids in Dietary Fats and Oils From 14 European: Countries: The TRANSFAIR Study

Trans Fatty Acids in Dietary Fats and Oils From 14 European: Countries: The TRANSFAIR Study

Uploaded by

pfradinho4993Copyright:

Available Formats

JOURNAL OF FOOD COMPOSITION AND ANALYSIS ARTICLE NO.

11, 137149 (1998)

FC980569

Trans Fatty Acids in Dietary Fats and Oils from 14 European Countries: The TRANSFAIR Study1

A. Aro,*,2 J. Van Amelsvoort, W. Becker, M.-A. van Erp-Baart, A. Kafatos, T. Leth, and G. van Poppel,3

*National Public Health Institute, Helsinki, Finland; Unilever Research Laboratory, Vlaardingen, The Netherlands; National Food Administration, Uppsala, Sweden; TNO Nutrition and Food Research, Post Ofce Box 360, 3700 AJ, Zeist, The Netherlands; Medicine and Nutrition Clinic, University of Crete, Heraklion, Greece; and National Food Agency, Sborg, Denmark Received July 3, 1997, and in revised form January 21, 1998 The fatty acid composition of dietary fats and oils from 14 European countries was analyzed with particular emphasis on isomeric trans fatty acids. The proportion of trans fatty acids in typical soft margarines and low-fat spreads ranged between 0.1 and 17% of total fatty acids and that of cis-unsaturated fatty acids between 55 and 81%. Hard household margarines and industrial fats for cooking and baking (shortenings) had slightly higher proportions of trans fatty acids and highest amounts, up to 50%, were found in fats for deep frying. Vegetable oils contained only small amounts of trans fatty acids, usually less than 1%. Isomers of C18:1 comprised up to 94% of the trans fatty acids in hardened vegetable oils and 52 68% in butter, whereas hardened sh oils showed a more even distribution of trans monoenoic fatty acids between C16:1 and C22:1, and C18:1 isomers contributed by 28 42% to total trans fatty acids. Fat spreads with very low content ( 1%) of trans fatty acids were found in all but one of the countries, and a general tendency to products lower in trans fatty acids was observed in most countries for soft margarines and low-fat spreads but not for industrial fats and fat products for cooking and frying. The fatty acid composition of the spreads indicated that both C1216 saturated fatty acids and cis-unsaturated fatty acids had been used to replace trans fatty acids in the low-trans fatty acid products in the different countries but the use of increased amounts of stearic acid was very limited. 1998 Academic Press

INTRODUCTION Fat spreads and fats used for cooking, baking, and frying are the main sources of isomeric trans fatty acids in the diet. Highest amounts of trans fatty acids are generally found in fats that contain partially hydrogenated vegetable or sh oils, whereas the amounts are smaller in butter and other fats from ruminants and quite low in unprocessed vegetable oils (Precht and Molkentin, 1995). Margarines and other spreads have been extensively analyzed (Akesson et al., 1981; Beare-Rogers et al., 1979; Carpenter et al., 1973; Croon, 1987; Demmelmair et al., 1996; Druckrey et al., 1985; Enig et al., 1983, 1984; Heckers et al., 1978; Kafatos et al., 1994; Katan et al., 1984; Kochhar and Matsui, 1984; Lake et al., 1996; Lercker et al., 1987; deMan et al., 1991; Marchand et al., 1982; Molkentin and Precht, 1995; Ottenstein et al., 1977; Ovesen et al., 1996; Parodi, 1976; Perkins et al., 1977; Pfalzgraf et al., 1993; Renner and Yoon, 1982a,b; Slover et al., 1985; Smith et al., 1978; Weihrauch et al., 1977; Wolff and Sebedio, 1991) but few reports are

1 2

This paper was prepared by the Authors on behalf of the TRANSFAIR study group (see Appendix 2). Working at TNO as a Visiting Scientist for the Academy of Finland. 3 To whom correspondence and reprint requests should be addressed. 137 0889-1575/98 $25.00

Copyright 1998 by Academic Press All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

138

ARO ET AL.

available on the composition of shortenings, cooking and frying fats (Enig et al., 1983; Heckers et al., 1978; Molkentin and Precht, 1995; Ovesen et al., 1996; Pfalzgraf et al., 1993), particularly of those used by the food industry for bakery products, deep-fried foods, etc. Ever since the unfavorable effects of dietary trans fatty acids on serum lipoproteins were conrmed (Katan et al., 1995) and their possible associations with risk of coronary heart disease were suggested (Willett and Ascherio, 1994) there has been a tendency to reduce the amounts of trans fatty acids in margarines, particularly in the European countries (Mickels and Sacks, 1995; Taylor, 1995). In Denmark it was recommended to reduce the proportion of trans fatty acids to less than 5% of fatty acids in retail margarines (Stender et al., 1995). Substitution of stearic acid for trans fatty acids has been recommended (Grundy, 1990; Katan, 1995), but except for Denmark (Ovesen et al., 1996), there are no follow-up data which would indicate how the reduction of trans fatty acids has affected the fatty acid composition of margarines and other dietary fats. In the European multicenter TRANSFAIR Study comprising 14 countries, samples of foods contributing to 95% of total fat intake were collected within a period of 1 year in 19951996 and analyzed centrally (van Poppel et al., 1997). In this paper the fatty acid compositions of various dietary fats are reported, indicating the proportions of trans fatty acids and saturated (SFA) and cis-unsaturated fatty acids of total fatty acids. MATERIALS AND METHODS Sampling of Foods4 The participating countries were Belgium (BEL), Denmark (DEN), Finland (FIN), France (FRA), Germany (GER), Greece (GRE), Iceland (ICE), Italy (ITA), The Netherlands (NET), Norway (NOR), Portugal (POR), Spain (SPA), Sweden (SWE), and the United Kingdom (UKI). Lists of foods contributing to 95% of total fat intake were prepared in each country based on data from recent nutrition surveys. For practical reasons the number of foods was reduced to 100 or less in each country by selection among foods with similar fat composition and by the production of aggregates of different brands of similar foods, based on existing information on market shares, if available. The foods were sampled during 1 year in 19951996, homogenized, frozen at 20C, and transported to The Netherlands for centralized analysis (van Poppel et al., 1997). Analytical Methods The analytical methods are described in detail elsewhere (van Poppel et al., 1997). Briey, the fats were extracted, the total fat content was determined, and the fatty acid methyl esters were separated by capillary gas chromatography. The fatty acids were identied by comparison with standards. A total of 44 fatty acids or groups of fatty acids with 8 to 26 carbon atoms were identied including 7 trans isomers. The C18:1 trans fatty acids, the C18:2 trans isomers, and the C18:3 trans C20:1 trans fatty acids were calculated as groups because of incomplete separation between individual fatty acid isomers.

4

Analyses of all (1299) TRANSFAIR samples are available on oppy disk (200 ECUs).

TRANS FATTY ACIDS IN DIETARY FATS AND OILS FROM EUROPE TABLE 1 The Fatty Acid Composition (Percentage of Methyl Esters) of Soft Table Margarines in the Different Countries

139

RESULTS The fatty acid compositions of margarines, low-fat spreads, and fats for frying and for cooking and baking from the participating countries are given in Tables 1 4. A typical or average product is given for each country. This is either the market leader for the country or an aggregate based on market shares. For margarines and low-fat spreads the product with the lowest and the highest proportion of total trans fatty acids in each country is included as well.

140

ARO ET AL. TABLE 2

The Fatty Acid Composition (Percentage of Methyl Esters) of Low-Fat Spreads in the Different Countries

Variable amounts of trans fatty acids were found in the margarines and low-fat spreads of different countries (Table 1). The typical soft table margarines of France, The Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden contained very low amounts of trans fatty acids, and in Denmark and Finland aggregates of products based on market shares showed relatively low proportions of trans fatty acids, too. Iceland and Norway showed a totally different pattern with the most popular brands being high in trans fatty acids, and the aggregate of soft margarines from the UK included sh-derived trans isomers. Margarines that were virtually free of trans fatty acids were found in all countries except for Norway. In Sweden

TRANS FATTY ACIDS IN DIETARY FATS AND OILS FROM EUROPE TABLE 3 The Fatty Acid Composition (Percentage of Methyl Esters) of Hard Household Margarines in the Different Countries

141

all soft margarines contained only very small amounts of trans fatty acids. The low-fat spreads showed corresponding differences between the countries (Table 2). The margarines with low trans fatty acid content showed several differences in their fatty acid composition. The Swedish margarines were highest in SFA, particularly in C12-16:0 fatty acids. On the other hand the Dutch and Belgian margarines were particularly low in SFA and high in cis-unsaturates. Also in Greece, Portugal, Spain, and the UK low-trans fatty acid margarines with an increased share of cis-unsaturates were found. In France low-trans fatty acid products had been produced both by increasing C12-16 saturated fatty acids and by increasing cis-unsaturates. In Germany the most popular

142

ARO ET AL. TABLE 4 The Fatty Acid Composition (Percentage of Methyl Esters) of Butter and Fats for Frying, Cooking, and Baking in the Different Countries

margarine was characterized by a high contribution of stearic acid and cis-unsaturated fatty acids but in the low-trans fatty acid product these were partially replaced with C12-16 SFA. The Danish and the Finnish margarines were rather similar and trans fatty acids had been largely replaced by both C12-16 SFA and unsaturated fatty acids. In about one-half of the countries the margarine that was lowest in trans fatty acids contained more

TRANS FATTY ACIDS IN DIETARY FATS AND OILS FROM EUROPE TABLE 5 The Fatty Acid Composition (Percentage of Methyl Esters) of Selected Fats for Frying and Cooking in the Different Countries

143

SFA than the average product, and this was not due to differences in stearic acid (Tables 1 and 2). Among household hard margarines the Icelandic and Norwegian brands again differed from the others in containing high proportions of trans fatty acids and lower proportions of cis-unsaturates (Table 3). Hard margarines with low and high amounts of trans fatty acids were found in most countries, however. Most of the typical frying fats contained high amounts of trans fatty acids (Table 4). The fat products with highest proportions of trans fatty acids were found within this group of foods. The typical French product was an exception. It was an extremely highly saturated coconut-based product that contained negligible amounts of both cis- and trans-unsaturated fatty acids. The partially hydrogenated vegetable fats contained mainly C18:1 trans fatty acids, little or no other monoenoic trans isomers, and some C18:2 trans fatty acids. Products containing hydrogenated sh oil were characterized by a more even distribution between C16:1, C18:1, C20:1, and C22:1 trans isomers, whereas butter contained mainly C18:1 trans fatty acids with smaller proportions of both C16:1 and C18:2 isomers (Table 5). The partially hydrogenated sh oils contained also numerous long-chain cis- and trans-isomers that could not be identied and were therefore included in the group of unidentied fatty acids. Only minor amounts of trans fatty acids were found in the vegetable oils but the composition of trans isomers differed between the oils (Table 6). Olive oil, both virgin and rened types, contained practically no trans fatty acids. Rened sunower and soybean oils contained generally more C18:2 trans isomers than C18:1 trans fatty acids. Corn oil samples from Iceland and Portugal contained more than 1% of C18:2 trans

144

ARO ET AL. TABLE 6

The Fatty Acid Composition (Percentage of Methyl Esters) of Vegetable Oils in the Different Countries

isomers but not the corn oil from France and Germany. C18:3 trans isomers were found in those oil samples that contained soybean oil or rapeseed oil. Spanish oils that had been reutilized for deep frying of beef or sh contained slightly more trans isomers than unused rened oils (Table 7). Mainly C18:2 trans fatty acids were increased, and the highest proportion (0.89%) was found in sunower oil that had been repeatedly used at restaurants until discarded.

TRANS FATTY ACIDS IN DIETARY FATS AND OILS FROM EUROPE TABLE 7 The Fatty Acid Composition (Percentage of Methyl Esters) of Mixed and Reutilized Oils in the Different Countries

145

DISCUSSION The sampling in each country was based on foods contributing to 95% of total fat intake but the nal selection was done according to the local method of calculating intakes, since the main objective of the sampling procedure was to allow the calculation of trans fatty acid intake in the participating countries, to be reported separately. Soft margarines and low-fat spreads were sampled in all countries. In most of them several individual brands were sampled, whereas in others aggregates of products were prepared based on market shares. Industrial fats and shortenings for cooking and baking and fats for deep frying were analyzed separately in many countries but in others like Denmark, Italy, Spain, and Sweden the contributions of these fat products were estimated from the analysis of processed foods. Therefore the products that are included into the tables are not exactly comparable in all aspects but they still give an indication of the typical fat products that are used and the ranges of fatty acid compositions in the different countries. The results indicate that the proportion of trans fatty acids in soft margarines has been reduced by several means. Trans fatty acids were replaced by C12-16 SFA from palm oil or coconut oil but it was also possible to increase the proportion of cis-unsaturated fatty acids in the products. Examples of both these ways to produce low-trans fatty acid fat

146

ARO ET AL.

spreads were found among the products of the different countries. The low-trans fatty acid margarines of France and Sweden (Table 1) contained particularly high proportions of lauric acid (C12:0), suggesting the use of coconut oil. In several countries like Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the UK, margarines with low amounts of trans fatty acids had been produced by increasing the proportion of cis-unsaturated fatty acids. The German margarines were highest in stearic acid but otherwise there was no clear evidence of specic attempts to increase the proportion of stearic acid in the products. Information from the food industry and from certain studies indicated that the proportion of trans fatty acids in margarines and low-fat spreads had been reduced in many countries during the year preceding the sampling in 19951996. This holds for Denmark (Ovesen et al., 1996), Finland, France (Bayard et al., 1995), and Sweden. In the Netherlands and Norway similar development was evident during or soon after the sampling. The changes were mainly voluntary but in Denmark the authorities had advised reduction in the trans fatty acid content of retail margarines and shortenings for industrial use (Stender et al., 1996). The changes in the fatty acid composition of margarines was monitored in Denmark and the results indicated that trans fatty acids were only partially replaced by SFA, partially by cis-unsaturates (Ovesen et al., 1996). The development in Sweden probably had been different since all soft table margarines contained very small amounts of trans fatty acids but particularly high amounts of SFA. In Finland domestic margarines that were sampled according to market shares were moderately low in trans fatty acids but recently marketed imported margarines that were not included in the market shares and were therefore sampled separately contained considerably higher amounts of trans fatty acids. It seems apparent that in some countries the old margarines have been exported at the same time as new low-trans fatty acid margarines have been developed. Comparison with earlier reports on the trans fatty acid content of margarines also indicated a clear reduction for Denmark, France, Germany, The Netherlands, and Sweden (Croon, 1987; Bayard et al., 1995; Druckrey et al., 1985; Heckers et al., 1978; Katan et al., 1984; Pfalzgraf et al., 1993; Wolff et al., 1991). In accordance with previous ndings (Carpenter et al., 1976; Kochhar and Matsui, 1984; Pfalzgraf et al., 1993), the vegetable oils contained very small amounts of trans fatty acids, less than 1% of fatty acids, with the exception of two corn oil samples from Iceland and Portugal. Since corn oil from France and Germany contained much lower amounts of trans isomers the difference probably depended on the processing of the oils. Olive oil, both unrened and rened, was particularly low in trans fatty acids. The rened sunower oil and soybean oil products contained more C18:2 trans than C18:1 trans. Reutilization of oils may increase the trans fatty acid content of oils due to exchange of fatty acids between the fried food and the oil and by the frying process itself (Leth, 1987; Sebedio et al., 1990). Reutilized oils studied in Spain contained somewhat more trans isomers than the native oils. The effect may be partly due to exchange of fatty acids between the fried foods and the oils, seen as an increase in C18:1 trans in the oil used for beef, but the increase in the proportion of C18:2 trans isomers probably reected the effect of reutilization. This was most marked in the discarded sunower oil that had been reutilized several times. Soybean oil and rapeseed oil and rapeseed oil-containing mixtures from Finland and Sweden contained C18:3 trans fatty acids which presumably were formed from alpha-linolenic acid during processing. Overall the differences between the different oils were rather small and mainly of theoretical interest. The spectrum of trans isomers in the fats indicated with some certainty the origin of the

TRANS FATTY ACIDS IN DIETARY FATS AND OILS FROM EUROPE

147

fat. Hardened sh oils could be distinguished from hardened vegetable oils and ruminant fats by looking at the distribution of trans monoenoic fatty acids with 16 to 22 carbon atoms. A fatty acid pattern typical for hardened sh oil (Ojanpera, 1978) could be identied in several cooking and frying fats from Iceland and Norway, in the aggregate of soft margarines from the UK and, occasionally, in other countries, and it was characteristic of numerous bakery products from several countries (van Erp-Baart et al., 1997). Hardened vegetable oils were more difcult to distinguish from dairy fat but the amount of C16:1 trans fatty acids was useful in many occasions. Roughly equal proportions of C16:1 and C18:2 trans fatty acids in addition to C18:1 trans were typical for ruminant fats, whereas most hardened vegetable oils contained mainly C18:1 trans, little or no C16:1 trans, and variable amounts of C18:2 trans fatty acids. Selected examples of fats from different origin (Table 5) showed the typical features of their declared ingredients. Frying fats and shortenings contained the highest amounts of trans isomers in the present study. We could not nd clear indications of a similar decline in the proportion of trans fatty acids that was evident for soft margarines and spreads. This is in agreement with the ndings of Bayard et al., (1995) from France. The highest amount of trans isomers, 50% of all fatty acids, was measured in a Dutch frying fat composed of partially hydrogenated vegetable oil. Bayard et al., (1995) found a brand of shortening with 62.5% trans fatty acids in their study in France but this product was not included in the samples of our study or its composition had been changed. In summary, a wide range of trans fatty acids was found in the European fat products. Soft tub margarines containing low amounts of trans fatty acids were available in practically all the countries. A tendency to products lower in isomeric trans fatty acids has been evident in most countries for soft margarines and low-fat spreads but not for industrial fats and fats for frying and cooking. In the different low-trans fatty acid products C12-16 saturated fatty acids and cis-unsaturated fatty acids or both had been used to replace trans fatty acids, but apparently stearic acid had not been used to any appreciable extent for that purpose. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The TRANSFAIR study is a concerted action supported by the Commission of the European Communities (AIR 2421). Centralized chemical analyses were supported by the industrial participants listed in Appendix 2 of Van Poppel et al. (this issue). The studies in each country were supported by national funds. We thank the participants listed in Appendix 2 of Van Poppel et al. (this issue) and numerous other coworkers that are not mentioned for their valuable contributions to this project.

REFERENCES

Akesson, B., Johansson, B.-M., Eng, M., Svensson, M., Eng, M., and Ockerman, P. A. (1981). Content of trans-octadecenoic acid in vegetarian and normal diets in Sweden, analyzed by the duplicateportion technique. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 34, 25172520. Bayard, C. C., and Wolff, R. L. (1995). Trans-18:1 acids in French tub margarines and shortenings: Recent trends. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 72, 14851489. Beare-Rogers, J. L., Gray, L. M., and Hollywood, R. (1979). The linoleic acid and trans fatty acids of margarines. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 32, 18051809. Carpenter, D. L., Lehmann, J., Mason, B. S., and Slover, H. T. (1976). Lipid composition of selected vegetable oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 53, 713718. Carpenter, D. L., and Slover, H. T. (1973). Lipid composition of selected margarines. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 50, 372376.

148

ARO ET AL.

Croon, L.-B. (1987). Fettsyrasammansattningen i matfett (The fatty acid composition of edible fats). Vr Foda, 39, 214. Demmelmair, H., Festl, B., Wolfram, G., and Koletzko, B. (1996). Trans fatty acid contents in spreads and cold cuts usually consumed by children. Z. Ernahrungswiss. 35, 235240. Druckrey, F., Hy, C.-E., and Hlmer, G. (1985). Fatty acid composition of Danish margarines. Fette Seifen Anstrichmittel 87, 350 355. Enig, M. G., Budowski, P., and Blondheim, S. H. (1984). Trans-unsaturated fatty acids in margarines and human subcutaneous fat in Israel. Hum. Nutr. Clin. Nutr. 38C, 223230. Enig, M. G., Pallansch, L. A., Sampugna, J., and Keeney, M. (1983). Fatty acid composition of the fat in selected food items with emphasis in trans components. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 60, 1788 1795. Grundy, S. M. (1990). Trans-monounsaturated fatty acids and serum cholesterol levels. N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 480 481. Heckers, H., and Melcher, F. W. (1978). Trans-isomeric fatty acids present in West German margarines, shortenings, frying and cooking fats. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 31, 10411049. Kafatos, A., Chrysadis, D., and Peraki, E. (1994). Fatty acid composition of Greek margarines. Margarine consumption by the population of Crete and its relationship to adipose tissue analysis. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 45, 107114. Katan, M. B. (1995). Exit trans fatty acids. Lancet 346, 12451246. Katan, M. B., Van de Bovenkamp, P., and Brussaard, J. H. (1984). Vetzuursamenstel ling, trans-vetzuur en cholesterolgehalte van margarines en andere eetbare vetten. Voeding 45, 127133. Kochhar, S. P., and Matsui, T. (1984). Essential fatty acids and trans contents of some oils, margarine and other food fats. Food Chem. 13, 85101. Lake, R., Thomson, B., Devane, G., and Scholes, P. (1996). Trans fatty acid content of selected New Zealand Foods. J. Food Comp. Anal. 9, 365374. Lercker, G., Zullo, C., and Tortorelli, A. (1987). Contenuto di trans isomeri negli acidi grassi delle margarine del commercio. Riv. Sost. Grasse 64, 469 473. Leth, T. (1987). Changes in fatty acid content of used frying fat compared with fresh fat. Fat Sci. Technol. 89, 258 260. deMan, L., Shen, C. F., and deMan, J. M. (1991). Composition, physical and textural characteristics of soft (tub) margarines. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 68, 70 73. Marchand, C. M. (1982). Positional isomers of trans-octadecenoic acids in margarines. Can. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. 15, 196 199. Michels, K., and Sacks, F. (1995). Trans fatty acids in European margarines (letter). N. Engl. J. Med. 332, 541542. Molkentin, J., and Precht, D. (1995). Determination of trans-octadecenoic acids in German margarines, shortenings, cooking and dietary fats by Ag-TLC/GC. Z. Ernahrungswiss. 34, 314 317. Ojanpera, S. H. (1978). Analysis of isomeric monoethylenic fatty acids in a partially hydrogenated herring oil by glass capillary gas liquid chromatography. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 55, 290 292. Ottenstein, D. M., Wittings, Walker, G., Mahadevan, V., and Pelick, N. (1977). Trans fatty acid content of commercial margarine samples determined by gas liquid chromatography on OV-275. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 54, 207209. Ovesen, L., Leth, T., and Hansen, K. (1996). Fatty acid composition of Danish margarines and shortenings, with special emphasis on trans fatty acids. Lipids 31, 971975. Parodi, P. W. (1976). Composition and structure of some consumer-available edible fats. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 53, 530 534. Perkins, E. G., McCarthy, T. P., OBrien, M. A., and Kummerow, F. A. (1977). The application of packed column gas chromatographic analysis to the determination of trans unsaturation. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 54, 279 281. Pfalzgraf, A., Timm, M., and Steinhart, H. Gehalte von trans-Fettsauren in Lebensmitteln. Z. Ernahrungswiss. 33, 24 43. Precht, D., and Molkentin, J. (1995). Trans fatty acids: implications for health, analytical methods, incidence in edible fats and intake. Die Nahrung 39, 343374.

TRANS FATTY ACIDS IN DIETARY FATS AND OILS FROM EUROPE

149

Puri, P. S. (1978). Correlations for trans-isomer formation during partial hydrogenation of oils and fats. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 55, 865 869. Renner, E., and Yoon, Y. C. (1982). Untersuchungen uber isomere Formen ungesattigter Fettsauren in Nahrungsfetten. 1. Isomere der Octadecdiensaure. Milchwissenschaft 37, 264 266 (a). Renner, E., and Yoon, Y. C. (1982). Untersuchungen uber isomere Formen ungesattigter Fettsauren in Nahrungsfetten. 2. Isomere der Octadecadiensaure. Milchwissenschaft 37, 408 411 (b). Sahasrabudhe, M. R., and Kurian, C. J. (1979). Fatty acid composition of margarines in Canada. J. Inst. Can. Sci. Technol. Aliment. 12, 140 144. Sebedio, J. L., Bonpunt, A., Grangirard, A., and Prevost, J. (1990). Deep fat frying of frozen prefried French fries: Inuence of the amount of linolenic acid in the frying medium. J. Agric. Food Chem. 38, 19621867. Slover, H. T., Thompson, R. H., Davis, C. S., and Merola, G. V. (1985). Lipids in margarines and margarine-like foods. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 62, 775786. Smith, L. M., Dunkley, W. L., Franke, A., and Dairiki, T. (1978). Measurement of trans and other isomeric unsaturated fatty acids in butter and margarine. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 55, 257261. Stender, S., Dyerberg, J., Hlmer, G., Ovesen, L., and Sandstrom, B. (1995). The inuence of trans fatty acids on health: A report from the Danish Nutrition Council. Clin. Sci. 88, 375392. Taylor, S. (1995). Trans fatty acids in margarine (letter). N. Engl. J. Med. 333, 130 131. Van Erp-Baart, M.-A., Couet, C., Cuadrado, C., Kafatos, A., Stanley, J., Van Poppel, G. (1997). Trans fatty acids in bakery products from 14 European countries: the TRANSFAIR Study. J. Food Compos. Anal. Van Poppel, G., Van Erp-Baart, M.-A., Leth, T., Gevers, E., Van Amelsvoort, J., Lanzmann-Petithory, D., Kafatos, A., and Aro, A. (1997). Trans fatty acids in foods in Europe: The TRANSFAIR study. Submitted. Weihrauch, J. L., Brignoli, C. A., Reeves, J. B. III, and Iverson, J. L. (1977). Fatty acid composition of margarines, processed fats, and oils: A new compilation of data for tables of food composition. Food Technol. 31, 80 91. Willett, W. C., and Ascherio, A. (1994). Trans fatty acids: Are the effects only marginal? Am. J. Public Health 84, 722724. Wolff, R. L., and Sebedio, J.-L. (1991). Geometrical isomers of linoleic acid in low-calorie spreads marketed in France. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 68, 719 725.

You might also like

- Grade 5 Performance Tasks - Science and Social StudiesDocument36 pagesGrade 5 Performance Tasks - Science and Social StudiesCourtney mcintosh100% (8)

- Spring Reset Mel RobbinsDocument26 pagesSpring Reset Mel RobbinsCyberPuro Nica100% (1)

- Voluntary Guidelines for Sustainable Soil ManagementFrom EverandVoluntary Guidelines for Sustainable Soil ManagementNo ratings yet

- Eu602 en 5Document14 pagesEu602 en 5Luz CamachoNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry of Fatty AcidsDocument5 pagesBiochemistry of Fatty AcidsMahathir Mohmed100% (4)

- 1118-Article Text-8617-1-10-20171212Document8 pages1118-Article Text-8617-1-10-20171212umrbekfoodomeNo ratings yet

- Eu602 en 6Document7 pagesEu602 en 6Laurence MillanNo ratings yet

- Joprv14n1 1Document8 pagesJoprv14n1 1krishnaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Fatty Acid Esters of Hydroxyl Fatty Acid in Nut Oils and Other Plant OilsDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Fatty Acid Esters of Hydroxyl Fatty Acid in Nut Oils and Other Plant OilsClaudia Marcela Cortes PrietoNo ratings yet

- Food Chemistry: Aftab Kandhro, S.T.H. Sherazi, S.A. Mahesar, M.I. Bhanger, M. Younis Talpur, Abdul RaufDocument5 pagesFood Chemistry: Aftab Kandhro, S.T.H. Sherazi, S.A. Mahesar, M.I. Bhanger, M. Younis Talpur, Abdul RaufMiguelcuevamartinezNo ratings yet

- 9-Trans Fatty Acids in Commercial Cookies and Biscuits An Update of Portuguese MarketDocument6 pages9-Trans Fatty Acids in Commercial Cookies and Biscuits An Update of Portuguese MarketumrbekfoodomeNo ratings yet

- Food Chemistry: Aftab Kandhro, S.T.H. Sherazi, S.A. Mahesar, M.I. Bhanger, M. Younis Talpur, Abdul RaufDocument5 pagesFood Chemistry: Aftab Kandhro, S.T.H. Sherazi, S.A. Mahesar, M.I. Bhanger, M. Younis Talpur, Abdul RaufsolmelaNo ratings yet

- The Essential Guide To Fatty Acid Analysis - Eurofins USADocument2 pagesThe Essential Guide To Fatty Acid Analysis - Eurofins USASmit patelNo ratings yet

- Chaves 2018Document34 pagesChaves 2018NovriamanNo ratings yet

- Anita Proj Chapter 1Document5 pagesAnita Proj Chapter 1Damilola AdegbemileNo ratings yet

- 13 IFRJ 20 (02) 2013 AftabDocument5 pages13 IFRJ 20 (02) 2013 AftabNimra NaveedNo ratings yet

- Trans Fatty Acids and Coronary Heart DiseaseDocument21 pagesTrans Fatty Acids and Coronary Heart DiseaseMiroljub BaraćNo ratings yet

- Occurrence of Trans-C18:1 Fatty Acid Isomers in Goat Milk: Effect of Two Dietary Regimens Is 0022030202740678Document8 pagesOccurrence of Trans-C18:1 Fatty Acid Isomers in Goat Milk: Effect of Two Dietary Regimens Is 0022030202740678Andreas MeyerNo ratings yet

- Akinola Et Al 2010 Physico-Chemical Properties of Palm Oil From Different Palm Oil Local Factories in NigeriaDocument6 pagesAkinola Et Al 2010 Physico-Chemical Properties of Palm Oil From Different Palm Oil Local Factories in NigeriaDhianRhanyPratiwiNo ratings yet

- Effects of Dietary Supplementation With Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae Atopic DermatitisDocument9 pagesEffects of Dietary Supplementation With Sea Buckthorn (Hippophae Atopic DermatitiswxcvbnnbvcxwNo ratings yet

- 24 MaizeeeDocument10 pages24 MaizeeeRizka ArianiNo ratings yet

- Fatty Acid Oil CompositionDocument10 pagesFatty Acid Oil CompositionĀĥMệd HĀşşanNo ratings yet

- Ferreira 2017Document10 pagesFerreira 2017CINTHIA ANDREA ESTRADA RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S0022030216305380-MainDocument6 pages1-S2.0-S0022030216305380-MainV Alonso MTNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Vegetable OilsDocument32 pagesAnalysis of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Vegetable Oilskurleigh17No ratings yet

- Food Research International 122 (2019) 318-329Document12 pagesFood Research International 122 (2019) 318-329umrbekfoodomeNo ratings yet

- Molecules: Biological and Nutritional Properties of Palm Oil and Palmitic Acid: Effects On HealthDocument23 pagesMolecules: Biological and Nutritional Properties of Palm Oil and Palmitic Acid: Effects On HealthHyung Sholahuddin AlayNo ratings yet

- Group 6-Trans Fat Issues SlideDocument29 pagesGroup 6-Trans Fat Issues SlideAn UmillahNo ratings yet

- Impact of Diets With Different Oil Sources On GrowDocument24 pagesImpact of Diets With Different Oil Sources On GrowMuhammad DannyNo ratings yet

- Optimization of Hydrocolloids Concentration On Fat Reduction in French FriesDocument6 pagesOptimization of Hydrocolloids Concentration On Fat Reduction in French FriesAJER JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Margarine and Butter Consumed in The UK, Germany and FranceDocument12 pagesComparative Life Cycle Assessment of Margarine and Butter Consumed in The UK, Germany and FranceputriNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three The Process Technology of Oil and Fat Industries Fat and OilDocument21 pagesChapter Three The Process Technology of Oil and Fat Industries Fat and Oilabdisahurisa24No ratings yet

- Fatty Acid CompositionDocument5 pagesFatty Acid CompositionAnonymous MhTaJsNo ratings yet

- Microbial LipidsDocument10 pagesMicrobial LipidsSharif M Mizanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Quality of Cold-Pressed Edible Rapeseed Oil in GermanyDocument7 pagesQuality of Cold-Pressed Edible Rapeseed Oil in Germanyelcyionstar100% (1)

- IaurtDocument16 pagesIaurtIndira MustafaNo ratings yet

- Polyunsaturated Ffaa in The Chain Fodd in EuropeDocument3 pagesPolyunsaturated Ffaa in The Chain Fodd in EuropealbedriasNo ratings yet

- Food Oils and Fats - Technology, Utilization, and Nutrition by DARRY LAWSONDocument348 pagesFood Oils and Fats - Technology, Utilization, and Nutrition by DARRY LAWSONMonalisha PattnaikNo ratings yet

- Effect of Heating On The Characteristics and Chemical Composition of Selected Frying Oils and FatsDocument6 pagesEffect of Heating On The Characteristics and Chemical Composition of Selected Frying Oils and FatsNiere AdolfoNo ratings yet

- Oxidation On The Stability of Canola Oil Blended With Stinging Nettle Oil at Frying TemperatureDocument15 pagesOxidation On The Stability of Canola Oil Blended With Stinging Nettle Oil at Frying TemperatureRoberto RebolledoNo ratings yet

- Food Control: R. Mignogna, A. Fratianni, S. Niro, G. Pan FiliDocument8 pagesFood Control: R. Mignogna, A. Fratianni, S. Niro, G. Pan FiliChindy Widya RahmaNo ratings yet

- Fatty Acids SaffolaDocument48 pagesFatty Acids SaffolaSunil MathewsNo ratings yet

- Fatty Acid FA Composition and Contents oDocument6 pagesFatty Acid FA Composition and Contents oPlácidoNo ratings yet

- DR Emanuel F Cummings Senior Lecturer in Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine - Ugsm/UgsdDocument53 pagesDR Emanuel F Cummings Senior Lecturer in Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine - Ugsm/Ugsdandrea titusNo ratings yet

- Food Chemistry 295 (2019) 198-205Document8 pagesFood Chemistry 295 (2019) 198-205BenzeneNo ratings yet

- Cjfs - CJF 202204 0008Document8 pagesCjfs - CJF 202204 000822071 Bryan ChangdrianNo ratings yet

- Manuscript AguacateDocument27 pagesManuscript AguacateLoredana Veronica ZalischiNo ratings yet

- Characteristics and Properties of Fatty Acid Distillates From Palm OilDocument7 pagesCharacteristics and Properties of Fatty Acid Distillates From Palm OilRony DwihartaNo ratings yet

- White Mineral OilDocument39 pagesWhite Mineral OilMohamed SabryNo ratings yet

- Food and Nutritional Analysis Oils and Fats-328-334Document7 pagesFood and Nutritional Analysis Oils and Fats-328-334fernandoferozNo ratings yet

- Heat-Oxidation Stability of Palm Oil Blended With Extra Virgin Olive OilDocument8 pagesHeat-Oxidation Stability of Palm Oil Blended With Extra Virgin Olive OilMaria Celina Machado de MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Fernandes Etal2018caracteriacionaceitesDocument13 pagesFernandes Etal2018caracteriacionaceitescinthyakaremNo ratings yet

- Cornicabra TG AG-FoodChem 2004Document8 pagesCornicabra TG AG-FoodChem 2004baglamaNo ratings yet

- Cme 2013 010306Document8 pagesCme 2013 010306Anoop KalathillNo ratings yet

- Applied Sciences: Commercial Hemp Seed Oils: A Multimethodological CharacterizationDocument15 pagesApplied Sciences: Commercial Hemp Seed Oils: A Multimethodological CharacterizationNop PiromNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0026265X09000526 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0026265X09000526 Mainhongthuy0811No ratings yet

- Lipids Food Chemistry Chap 3Document31 pagesLipids Food Chemistry Chap 3Adisu ButaNo ratings yet

- Trait-Modified Oils in FoodsFrom EverandTrait-Modified Oils in FoodsFrank T. OrthoeferNo ratings yet

- Fats and Fatty Acids in Human NutritionFrom EverandFats and Fatty Acids in Human NutritionNo ratings yet

- Tackling Climate Change through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation OpportunitiesFrom EverandTackling Climate Change through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation OpportunitiesNo ratings yet

- Case Study #2Document3 pagesCase Study #2SABINA KYLE MANAGBANAGNo ratings yet

- Nursing Informatics Reviewer (Lab)Document190 pagesNursing Informatics Reviewer (Lab)Raquel MonsalveNo ratings yet

- BurgosDocument723 pagesBurgosMaricel DumanasNo ratings yet

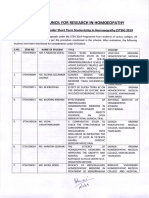

- Central Council For: in HomoeopathyDocument18 pagesCentral Council For: in Homoeopathy9891233665No ratings yet

- Eq I Yv BrochureDocument2 pagesEq I Yv BrochureLupu AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Construction Site Safety: Accident Reporting and InvestigationDocument11 pagesConstruction Site Safety: Accident Reporting and InvestigationProfessional TrustNo ratings yet

- Dela Rosa-Module 6Document8 pagesDela Rosa-Module 6DELA ROSA, RACHEL JOY A.No ratings yet

- The Anchorage Bend in The Begg TechniqueDocument7 pagesThe Anchorage Bend in The Begg TechniqueSyed Mohammad Osama AhsanNo ratings yet

- Hearing Aid DataDocument16 pagesHearing Aid DataUdayan AwasthiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0260691722002039 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0260691722002039 MainQomaruddin Asy'aryNo ratings yet

- Peace, Conflict, and ViolenceDocument16 pagesPeace, Conflict, and ViolenceJustine DiazNo ratings yet

- CSP Chintu Anna - 1Document12 pagesCSP Chintu Anna - 1sujithNo ratings yet

- Awareness of Injury Prevention 1Document11 pagesAwareness of Injury Prevention 1Avegaile PaduaNo ratings yet

- PE-10-Quarter2-Week3-4-Module2 (Health&Wellness) - Baltazar - Ramil.et AlDocument16 pagesPE-10-Quarter2-Week3-4-Module2 (Health&Wellness) - Baltazar - Ramil.et AlShekinah Joy Arellano ViloriaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 12 - Diagnosis and Treatment - 2011 - McCracken S Removable Partial Pros PDFDocument35 pagesCHAPTER 12 - Diagnosis and Treatment - 2011 - McCracken S Removable Partial Pros PDFFlorin Razvan CurcăNo ratings yet

- Apa Ethics Violations On The Zimbardo ExperimentDocument7 pagesApa Ethics Violations On The Zimbardo Experimentapi-656182395No ratings yet

- PhysicalEducation SrSec 2022-23Document4 pagesPhysicalEducation SrSec 2022-23Rashid AliNo ratings yet

- Herbs - Invigorate BloodDocument13 pagesHerbs - Invigorate BloodyayanicaNo ratings yet

- Laboratory 1. Anatomical Position and TerminologiesDocument2 pagesLaboratory 1. Anatomical Position and TerminologiesAANo ratings yet

- Self Testing ActivitiesDocument6 pagesSelf Testing ActivitiesNina ManlangitNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Surgery: Prospective Cohort StudyDocument7 pagesInternational Journal of Surgery: Prospective Cohort StudyAkbar Adrian RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Low Cost PVC CrutchesDocument2 pagesLow Cost PVC CrutchesMohd Asri TaipNo ratings yet

- Manav Mangal High School, Chandigarh Holiday Home Engagement AssignmentDocument46 pagesManav Mangal High School, Chandigarh Holiday Home Engagement AssignmentArshdeep singhNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles in Plastic Surgery (Surgical FlapsDocument17 pagesBasic Principles in Plastic Surgery (Surgical FlapsMs. Priya MahtoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 5Document132 pagesChapter 1 5Kylle AlimosaNo ratings yet

- Police Abolition 101Document40 pagesPolice Abolition 101Salome Cortes RoblesNo ratings yet

- Lec - 4 - Population Pyramids - L.U - Feb - 19Document26 pagesLec - 4 - Population Pyramids - L.U - Feb - 19MOSESNo ratings yet

- Thyroid Related Thesis TopicsDocument5 pagesThyroid Related Thesis Topicsdwnt5e3k100% (2)