Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sino-Israeli Relations and Associated Impact On Arab-Israeli Relations, 1949-1993

Sino-Israeli Relations and Associated Impact On Arab-Israeli Relations, 1949-1993

Uploaded by

Malcolm ScottOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sino-Israeli Relations and Associated Impact On Arab-Israeli Relations, 1949-1993

Sino-Israeli Relations and Associated Impact On Arab-Israeli Relations, 1949-1993

Uploaded by

Malcolm ScottCopyright:

Available Formats

Author: Malcolm Scott Date: April 23, 2012 Sino-Israeli Relations and Associated Impact on Arab-Israeli Relations, 1949-1993

Vacillations between pragmatic and ideologically driven foreign policy have driven the relationship between the Israeli and Chinese governments over the time period 1949-1993. The Peoples Republic of China alternated between relatively pragmatic foreign policy to extend its own international influence and relatively ideological foreign policy to attempt fulfillment of specific aspirations. Earlier in the stated time period, interactions with the Soviet Union and Arab states in the Middle East limited Sino-Israeli relations, and this would be the situation even when the Chinese government attempted to pursue pragmatic foreign policy. Only at the end of the Cold War and the establishment of the Camp David Peace Accords did the Chinese government manage to be constructive in Sino-Israeli relations and the Arab-Israeli conflict in its pursuit of pragmatic foreign policy. For clarity, the Peoples Republic of China is noted as the government of China compared to the Republic of China noted as Taiwan.

1949-1955 A combination of ideological and geopolitical restrictions hindered relations between Israeli and Chinese government relations during the 1950s. The problem potentially existed even at the inception of the Chinese nation. When the Chinese Communist Party achieved sufficient victories and established the Peoples Republic of China in 1949, Mao Zedong stated the geopolitical and ideological problems associated with Sino-Israeli relations (Behbehani 1981, 46). Mao Zedong had noted awareness of antagonism against Israel from the Arab world;

furthermore, he regarded relations with Israel problematic because of beliefs held about Israel as a conduit for imperial influence (Behbehani 1981, 46). At least publicly, Mao Zedong espoused beliefs that the United States, United Kingdom, France and West Germany were imperial powers exploiting Israel (Behbehani 1981, 46). However, from 1949 to 1952, it was not certain that this assessment would necessarily continued unchanged without the war of the United States in Korea. Initially promising relations between the State of Israel and the Peoples Republic of China deteriorated. Cold War geopolitics had essentially corroded early goodwill. Prior to 1955, the Peoples Republic of China had considered formal diplomatic ties with the State of Israel. On January 9, 1950, the State of Israel was the first government of the Middle East to recognize the Peoples Republic of China through a cable to Premier Enlai from Israeli foreign minister (Shichor 1979, 21). In its early pursuits of diplomatic ties with the Israeli state, Mao Zedong and the Chinese government had displayed a noticeable degree of pragmatism; the Chinese government was intent on further recognition within the international community, and it did not object to mere diplomatic ties with nations under American influence (Shichor 1979, 21). Once more, there was a divergence since 1949 in the appraisal of Israel between the Soviet Union and the Peoples Republic of China. While the Soviet government had already altered its assessment of Israel, the Chinese government maintained flexibility in relations with ideologically dissimilar governments such as Israel (Shichor 1979, 21-22). Indeed, Chinese diplomats for affairs in Moscow attempted to contact the Israeli legation present there in June 1950, but the Israeli government had earlier declined to establish a diplomatic site in Beijing and merely to maintain communications through its legation in Moscow (Shichor 1979, 23). Despite these events, the Israeli and Chinese governments remained on good terms, and, on September 19, 1950, Israeli

delegates supported a resolution that would have replaced Republic of China/Taiwan delegates with those of the Peoples Republic of China (Shichor 1979, 23). Without the intervention of external circumstances, it was unlikely that Chinese-Israeli relations would have failed so early and indefinitely. Indeed, the Chinese special representative in the Security Council specifically praised Israel as one of sixteen nations supporting the September resolution (Shichor 1979, 24). Until January 1951, there would have been little indication that the two governments would not develop full diplomatic ties with each other within coming ten years. However, the geopolitics associated with the Cold War proved to be a major divide for the Israeli and Chinese governments. The debates within the United Nations over the Korean War eventually led to failed relations between the Israeli and Chinese governments. At this point, there were significant divergences in preferred responses to the Korean War. The Chinese governments desired a conference of seven nations that would resolve the problem (Shichor 1979, 24). The Israeli government desired a different solution in which there would be a truce between warring sides; this was not acceptable to the Chinese government, because the Chinese government interpreted this Israeli proposal as a stratagem by which the United States could reorganize its military forces as the United Nations became mired in discussions (Shichor 1979, 24). This divergence on the issue of the Korean War was not enough for the Chinese government to part ways with the State of Israel. More specifically, while critical of this approach, the Chinese government did not directly criticize the Israeli government and had the North China News Agency note the disapproval of another delegate to the Israeli proposal (Shichor 1979, 24). As part of a long trend in Middle Eastern relations, the Chinese government attempted to balance ideology and pragmatism in its geopolitics. The Peoples Republic of China had its preferences and concerns

about the United States in Korean Peninsula, but it did not wish so quickly to ostracize and to repudiate a state willing to recognize its existence. As such, the Chinese government tried to balance these tensions with care. This did not succeed because tensions associated with Cold War politics would become greater, for which the State of Israel could also be torn between the United States and the Soviet Union. The dispute over preferred actions for the Korean War were not sufficient for ChineseIsraeli relations to disintegrate, but it created additional strains that rendered the relations brittle. The dispute strained Chinese-Israeli relations further on February 1, 1951: Israeli delegates and those from forty-three other nations considered China to be an aggressor in Korean Peninsula and condemned the Chinese government as such (Shichor 1979, 24). Based on Chinese editorial, the Chinese government was even willing to overlook this voting decision as pressure from the United States, and neither the Chinese government nor Israeli government were willing to cease dialogue with each other (Shichor 1979, 24). The Israeli foreign minister was still willing to communicate with Premier Enlai on good terms, and the Israeli government twice opposed resolutions impeding Chinese representation in the United Nations (Shichor 1979, 24). For this time, both governments may have found themselves entangled in Cold War politics, but both governments apparently to be realistic and to maintain mutual, open ties. If the Korean Peninsula had not been especially important to either government in their overall geopolitical plans, it would have been sensible not to sever ties even over this war. However, by this time, the relationship was under duress, and the impact of the superpowers and other Middle Eastern states would enter more strongly into the political calculations of the Israeli and Chinese governments. Wavering strength of Soviet-Israeli relations impacted the strength of Chinese-Israeli relations. During late 1952 and early 1953, Chinese sentiments toward the Israeli government

became noticeably hostile (Shichor 1979, 24). This paralleled the severed ties of the Israeli and Soviet governments, and this time was also when the Chinese government more openly condemned Israel and Zionism in general (Shichor 1979, 25). However, Chinese relations with Israel improved at the same time as the Soviet relations with Israel later in 1953 (Shichor 1979, 25). During 1954, Israeli and Chinese relations quickly became cordial again (Shichor 1979, 25). However, because of Chinese activities at the Bandung Conference, the Chinese government was more discrete and cautious in its relations with the Israeli government during 1955 (Shichor 1979, 25). Within the space of three years, from 1952 to 1955, the Chinese relations with the Israeli government fluctuated considerably. The attitude of the Chinese government could vary between cordiality, hostility or neutrality depending on Soviet attitudes and Chinese relations with other Middle Eastern states. Sometimes, the Chinese government was ideological in its geopolitical affairs and was pragmatic in other circumstances. These vacillations demonstrated a conflict between ideology and pragmatism within Chinese government and its choices of foreign policy. Mao Zedong and the Chinese government in general tried to employ careful logic and choices of distinctions to balance ideology and pragmatism. It is important to note that Mao Zedong maintained a belief about the role of different regions and countries as buffers between the United States and the Soviet Union. Zedong had a belief known as the Intermediate Zone Theory (Shichor 1979, 12). During World War II, Mao Zedong had observed that the key regions existed between major fighting powers, and he had extrapolated this observation to the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union (Shichor 1979, 11). His expectation was that the United States would try to acquire control of key regions to gain an advantage over the Soviet Union (Shichor 1979, 12). Lu Ting-Yi, Director of the Department of Information at the Chinese

Communist Party, expounded that a collection of neutral territories existed between the United States and the Soviet Union (Shichor 1979, 12). A result of this perspective was that Chinese government had a key priority to inhibit what it perceived as imperial expansions in the Middle East, and this ideological perspective had a dimension of national security; activity by seemingly hostile powers was a deemed concern for national security (Shichor 1979, 12). However, Israel would not necessarily have fallen into the category during the 1950s at all. Any concerns about Israel as a security threat as interpreted in the Intermediate Zone theory probably occurred after the early 1950s mostly. This assessment probably was concurrent with the rise in ideology in Chinese foreign policy, but this is contextual to the ideological, Cold War geopolitics in general. Within this perspective, Israel was not necessarily significant itself as much as its believed use for ends threatening Chinese security. An integration of ideological and national security was a main barrier for relations between Chinese and Israeli governments, but it was arguably secondary to the greater role the Chinese government desired in the international system.

1955-1964 There was an early ideological antagonism of the Chinese government towards the Israeli government in the mid 1950s period as being conceived as an extension of Western imperialism (Behbehani 1981, 20). However, ideology would not necessarily have been such a great hurdle in mutually beneficial relations between the Israeli and Chinese governments. Common expectations in the Chinese government were that the role of the United States in Israeli affairs would decline, and the Israeli Communist Party expectedly held the role to facilitate the decline (Behbehani 1981, 20). The Chinese government placed a higher premium on international

recognition and also recognition by Arab states in particular (Behbehani 1981, 20). This was the greatest impetus for nominal support of Palestinian refugees (Behbehani 1981, 20). Examination of these circumstances indicates that the Chinese government did not necessarily have ideological inclinations to oppose Israeli nationalism and policies indefinitely; likewise, the government would not set its support for the Palestinian cause in stone. Indeed, the Peoples Republic of China pragmatically managed to integrate its ideological inclinations into an equally pragmatic foreign policy. However, specific circumstances impacted the degree of support for either Arabs and Palestinians or Israelis. The Bandung Conference was a significant event impacting Sino-Israeli relations and not merely Sino-Arab relations. On April 18-24, 1955, the Conference of Afro-Asian States convened in Bandung, Indonesia, in which Arab states formed significant blocs (Behbehani 1981, 21). Attending states often focused on issues about colonialism and national independence from colonial legacies (Behbehani 1981, 21). Part of this conference included efforts by Arab states to further the cause of Palestine and interests of Arab nationalism beyond the limits of the Cold War (Behbehani 1981, 21). Gamal Abdel Nasser was especially vocal for these issues (Behbehani 1981, 21). The Chinese Premier Chou Enlai discovered the strength of Arab states to discuss Palestinian issues; perceiving the pivotal role of Palestine amongst those states, Premier Enlai then offer Nasser and PLO Chairman Ahmad al-Shukairy his support for the Palestinian issue, which took many Arab representatives by surprise (Behbehani 1981, 21-22). That this demonstration of support by Enlai was unexpected is a probable indicator of decisional randomness. Indeed, there was no ideological preference at stake in Chinese support of Palestinians. The greatest priority for Premier Enlai was greater Chinese recognition in the international system; if that involved address of the Palestinian issue in order to curry favor with

Arab regimes, that would not have been a problem. If the Chinese government also managed to balance Arab and specifically Egyptian relations with Israeli relations, there would not have been any dilemmas of principle. The Chinese government had optimal flexibility within which to manage international relations. The Bandung Conference marked a circumstance in which pragmatic foreign policy had the greatest emphasis and flexibility was generous. This perspective is noticeable from analyses of a speech at the Bandung Conference by Enlai (Behbehani 1981, 22). During his speech on April 19, 1955, Enlai stressed nonviolent coexistence between ideologically and culturally differing states and assured no intentions of Communist propagation; indeed, an imam was among those of the Chinese delegation (Behbehani 1981, 22-23). These circumstances demonstrate that the Peoples Republic of China had to exercise pragmatism to maintain relationships with states ideologically and culturally dissimilar to each other and the Chinese state. The Chinese government during the 1950s had to exercise pragmatism out of necessity regardless of ideological preferences, and short-term exercises of pragmatism in the context of Cold War politics had prompted greater favor of Arab states and the Palestinian cause compared to the new Israeli nation. However, pragmatism not simply demanded better relations with more states but also greater influence in the international sphere based on immediate geopolitical circumstances. The decisions of the Chinese government at the Bandung Conference were pivotal to its international relations within the Middle East. There had been almost no formal relations between the Peoples Republic of China and the states of the Middle East prior to the Bandung Conference (Shichor 1979, 20). Middle Eastern states typically did not have a positive regard for the Chinese government (Shichor 1979, 20). Prior to the conference, the Chinese government

had to manage its relations through left-wing movements in countries of the Middle East (Shichor 1979, 20). All else being considered, it made sense for the Peoples Republic of China to support Palestinians nominally and to access numerous Middle Eastern states into the future. By comparison, Israel was one nation within the Middle East of which simply its very existence provoked the wrath of the Arab world. Due to the strategic nature of the pro-Palestinian support, the Arab-Israeli conflict did not actually merit violent conflict or military intervention from the perspective of the Chinese government. The Peoples Republic of China desired to acquire better security and Middle Eastern relations, but the government did not invest itself in the elimination of the Israeli state. Opposition to the United States was significantly fuelling the Chinese perspective on the Arab-Israeli conflict. Initially, from the Bandung Conference and 1963, the Chinese government focused on what it regarded as American exploitation of the Israeli state against the Arab states, and Palestinians themselves were not particularly important in this regard (Behbehani 1981, 23). As was common during the Cold War, the Arab-Israeli conflict was a proxy war with the United States, and contents of one author Tsui Chi from The Peoples Daily during these years reflecting the different aspects of this perspective (Behbehani 1981, 23). Chi had written that the United State was fomenting ill will between the Israeli and Egyptian states, and this was supposedly to use Israel against Egyptian sovereignty (Behbehani 1981, 23). That support for Arab states in a proxy war was even then still pragmatic, as indicated by another release of The Peoples Daily, in a section known as the Observer; the advocated perspective was that peaceful negotiations were essential to resolve the Palestinian problem (Behbehani 1981, 23). In this article, the writer deemed it necessary that there would be consultations with countries in the region according to United Nations procedures and that there be no military force (Behbehani 1981, 23). This is a

notable contrast to anti-Israeli belligerence of Arab states during the 1956 and 1967 wars. The contrast also indicates the motivations of the Chinese government at the time. The Chinese government then was not an advocate of Israeli elimination as much as resolution of the Palestinian problem. Their stance towards Israel during the 1956 War and Suez Crisis is notable in the use of ideology. During October and November of 1956, the Chinese expressed its opposition to intervention by the United Kingdom and France, but there was not an attempt to identify Israel as an aggressor (Behbehani 1981, 24). The Soviet Union identified Israel specifically as an instigator, but the U.S.S.R. identified that role as a part of a war between Israel and Egypt planned by Britain and France (Behbehani 1981, 24). China and the Soviet Union generally agreed about the role of the Israel in the Suez Canal crisis, and they had allocated blame to the declining imperial powers. This was actually in accordance with pragmatic policy procedures. However, it is important to deconstruct pragmatic nature of Chinese public relations at this time and its harmonization with ideological preferences. Pragmatism in foreign policy is necessary to understand Chinese blame towards Western powers and Israel in the 1956 Suez Crisis. The Chinese government had made distinctions between primary and secondary enemies in its Middle Eastern foreign policy (Shichor 1979, 14). Primary enemies were always meant to be the target of the Communist struggle, but secondary enemies were less dangerous and would be acceptable partners in temporary alliances (Shichor 1979, 14). Previous press statements from official Chinese news, the statements of the Premier Chou Enlai and the Chinese response during the Suez Crisis indicate that the Chinese government had regarded Israel as a secondary enemy. The Chinese government expressed ideological antagonism towards what it claimed was Western imperialism, but the government also made these distinctions between primary and secondary enemies. This was not an optimal

10

relationship between the Chinese and Israeli governments, but this classification nevertheless probably kept the possibility open for better Chinese-Israeli relations in the future. The greatest driver for Chinese partiality in the Arab-Israeli conflict was the pursuit of recognition by Arab states. The Peoples Republic of China received recognition from forty nine states by 1965, and only eight of those states were predominantly Arab (Behbehani 1981, 31). During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, only the Peoples Democratic Republic of Yemen recognized the Chinese government (Behbehani 1981, 31). Nominally siding with the Palestinians in the Arab-Israeli conflict, vis--vis Arab governments, was a means to build relationships with Arab states (Behbehani 1981, 31). Greater collaboration with Arab states via support for Palestinians was a means towards greater influence in the Middle East and recognition by Arab states. There was not significant ideological opposition to Israel, but it was less expedient for greater influence in world affairs and less feasible in the context of Cold War politics. If there had been fewer Cold War tensions and better relations with many Arab states already in place during this time, antagonism of the Chinese government towards the Israeli state would have been weaker if not non-existent. These conditions are present more so during the 1990s, but those different circumstances required changing geopolitical and internal Chinese dynamics in the decades prior to the 1990s.

1964 and 1967 Arab-Israeli War/Six Day War to 1970 At the summit of the Cultural Revolution, Chinese foreign policy became especially radical. The Chinese government under Mao Zedong had become particularly supportive of movements and military attempts deemed derivative of popular sovereignty (Behbehani 1981, 56). This was more the case after the 1967 war, but in the buildup to the 1967 Arab-Israeli war,

11

the Chinese government became vehemently supportive of Arab regimes and the Palestinian cause (Behbehani 1981, 56). This is a noticeable difference of the previous decade, and it is also a revealing indicator of the implications of the Cultural Revolution. From the time 1964 to the year 1973, the radicalized Chinese government apparently renounced much of its pragmatic policies of the previous decade. Whereas support for either sides in the Arab-Israeli conflict was tempered during the previous decade, the Chinese government more overtly supported the use of force by Arab states immediately before the war (Behbehani 1981, 56). Support for revolutionary movements represented a startling change in Chinese foreign policy. This immense change was noticeable at numerous levels. On June 5, 1967, a publication of The Peoples Daily disclosed statements of Chairman Mao to the effect that enemies of the Arab states would essentially be wiped out if the enemies were to fight, and Israel was among the considered enemies (Behbehani 1981, 57). While the Chinese government was trying to balance good relations with both Israeli and Arab states during the 1950s, the Chinese government is explicitly, violently pro-Arab and pro-Palestinian. The Chinese government during the 1950s preferred to use mediation to resolve the regional disputes of the Arab-Israeli conflict, whereas the government during the 1960s was openly supportive of grassroots revolutions to propagate ideology. The increasing radicalization of politics within the Chinese government was the Cultural Revolution is the most noticeable cause of these dramatic changes in policies. In light of this radicalization and the desire to support peoples movements, the Palestinian movement offered one of the few avenues to accomplish this during the 1960s (Ismael 1986, 210).

1970-1994

12

The ideological element strongly expressed in Chinese foreign policy goes into decline after 1970. During 1971 and 1972, the Chinese government began to reestablish ties with nations in the Middle East it had previously criticized as being imperialist, including Lebanon, Kuwait, Iran and Turkey (Ismael 1986, 213). During the decade, many nations voted in effort of Chinese expulsion from the United Nations, and few Middle Eastern states had voted otherwise although with many abstentions (Ismael 1986, 213). However, the Chinese government had diplomatic ties with more Middle Eastern states by 1979 (Ismael 1986, 213). In addition, as Soviet influence in the Middle East decline, Chinese involvement in the region and its more aggressive support for the PLO also subsided (Ismael 1986, 214-215). At this time, the more pragmatic foreign policy more visible during the 1950s became increasingly visible again. The Chinese government had underwent internal power struggles, and the government was probably also reacting to increasing international isolation. In response to these internal and external circumstances, the Chinese government probably then decided to curtail its more radical variations of foreign policy. This would also permit a more but not entirely neutral stance towards the Arab-Israeli conflict, and these circumstances would improve the likelihood of better Chinese-Israeli relations. This would more be the case after the death of Mao Zedong. The death of Mao Zedong and the rise of Deng Xiaoping in the Peoples Republic of China in 1976 would eventually facilitate renewed ties between the State of Israel and the Peoples Republic of China. The regime of Deng Xiaoping had an emphasis on economic development, as internal conflicts petered and international recognition improved (Kumaraswamy 1999, 26). This was a turning point in Chinese-Israeli relations, as the Chinese and Israeli states were willing to engage in a defense partnership despite a lack of formal diplomatic ties (Kumaraswamy 1999, 26). The connection between political pragmatism and the

13

quality of Sino-Israeli relations continues to be noticeable even twenty years after the Bandung Conference. As soon as the Chinese government shifted to pragmatic foreign policy and away from revolutionary, violent ideology, there was groundwork for better relations between the Chinese and Israeli governments. This was with all circumstances in international relations aside. However, other circumstances of international relations would not be irrelevant, but changes in those circumstances would be more accommodating to the Chinese and Israeli governments. A shift in the Middle Eastern precedent would improve Sino-Israeli relations further after the rise of Deng Xiaoping. Specifically, the Camp David Accords are a significant shift in the relations between Israeli and Arab states even when the agreements involved simply Israel and Egypt. That the leading regional, Arab power in the Middle East was willing to seek a negotiated settlement to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict sent a distinct signal to the Chinese government (Kumaraswamy 1999, 27). With this change in the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Chinese government had greater flexibility to pursue Israeli relations (Kumaraswamy 1999, 27). Greater acceptability for negotiation and moderation most likely eased the capacity of the Chinese government theoretically to balance relations with Israel and other Middle Eastern governments. These shifts were not sufficient to open Chinese-Israeli relations, but these changes foreshadowed the better relations of the 1990s. Chinese and Israeli ties until the Peoples Republic of China and the State of Israel officially recognized each other on January 24, 1992 (Kumaraswamy 1999, 29). A significant component of this change in Chinese-Israeli relations and its impact on the Arab-Israeli conflict was the end of the Soviet Union. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Chinese government had fallen in and then out with the Soviet Union; after the death of Mao Zedong, the Chinese government had supported the PLO partly to try to outmaneuver the Soviet Union (Sufott 1997, 17). However, if the Soviet Union ceased to exist, a Sino-Soviet rivalry had

14

become irrelevant in parallel. Because the Soviet Union and the former Chinese regime of the Cultural Revolution no longer existed during the early 1990s, the Chinese government could manage to be on better official terms with the State of Israel, and it was for the first time in nearly forty years. These improved relations had positive impacts for the Madrid Conference and the Oslo Peace Accords. Improved Sino-Israeli relations marked a new, constructive role of the Peoples Republic of China in Arab-Israeli negotiations. A member of Israeli diplomatic ranks, E. Zev Sufott, described the positions of the Chinese government in the 1991 Madrid Conference as positive and supportive (Sufott 1997, 17). He further described their reception towards covert dialogue for the 1993 Oslo Accords as warmly welcomed in Beijing (Sufott 1997, 17). This was not at all the only issue of contention between China and Israel, but this change in negotiations between Israel, the PLO and China is notable. The attitude of Chinese officials in the 1990s was strikingly different compared to sentiments espoused in the 1960s. Sufott recalled that the Vice Foreign Minister Yang Fuchang emphasized direct Israeli-PLO negotiations (Sufott 1997, 18). Even during the 1990s, the Chinese government was conscious of its relations with Arab states (Sufott 1997, 19). As had been done during the 1950s, Chinese officials tried to manage conflicting international relations through pragmatism. The Chinese government was attempting to build relations with Israel but also sought to manage its relations with other Arab states, including the PLO. It is important to note conversations between the diplomatic team of Sufott and the Vice Minister Yang Fuchang. The minister noted that better Arab-Israeli relations would improve the viability of Sino-Israeli relations (Sufott 1997, 19). The vice minister then recommended more extensive dialogue between the PLO and Israeli that was away from public scrutiny, and this greater privacy would

15

then avoid the ire of other interested parties (Sufott 1997, 19). It is also important to note that Chinese willingness to engage with Israel was a direct result of suggestions by Arafat, in which he had hinted at the necessity of Arab-Israeli negotiations at a 1988 Geneva conference (Sufott 1997, 81). In attempts to manage conflicting relations, the Chinese government often merely reinforced trends peace negotiations in the 1990s as well as Arab-Israeli wars in 1967, because its primary interest was often those relations and management of alliances.

The Peoples Republic of China was not the most significant state actor in the ArabIsraeli conflict. To the extent that it was influential, the nature of influence depended on the nature of Chinese foreign policy and external geopolitical circumstances. As Cold War politics became increasingly irrelevant and Arab states began (not universally) to negotiate with the state of Israel, there was greater potential for Sino-Israeli relations, and there were then more opportunities for the Chinese government to mediate and to help enhance the dialogue between Israel and the Palestinians. These opportunities more easily fit into a foreign policy for which China has desired better international relations. As the Chinese government regained foreign policy pragmatism after the 1960s, changing international circumstances left the Chinese and Israeli government with an opportunity to build ties that decayed during the 1950s.

16

Works Cited Behbehani, Hashim S.H. Chinas Foreign Policy in the Arab World, 1955-1975: Three Case Studies. Kegan Paul International Ltd.: Boston, 1981. Print

Ismael, Tareq Y. International Relations of the Contemporary Middle East: A Study in World Politics. Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, 1986. Print.

Kumaraswamy, P.R. China and the Middle East: The Quest for Influence. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, 1999. Print

Shichor, Yitzhak. The Middle East in Chinas Foreign Policy. Cambridge University Press: New York, 1979. Print.

Sufott, E Zev. A China Diary: Toward the Establishment of China-Israel Diplomatic Relations. Frank Cass: Portland, Oregon. 1997.

17

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Landbank Vs BelistaDocument2 pagesLandbank Vs BelistaBruce Estillote100% (1)

- Maris Navico Manuals ECDIS900 Users Guide Rel LDocument309 pagesMaris Navico Manuals ECDIS900 Users Guide Rel LAdi Prasetyo100% (1)

- America Is in The Heart: TitleDocument5 pagesAmerica Is in The Heart: TitleMark Paul Santin GanzalinoNo ratings yet

- Misconduct in Public Office 24 Feb 2017Document25 pagesMisconduct in Public Office 24 Feb 2017GotnitNo ratings yet

- Important Dates:: The Nature and Operations of IASBDocument11 pagesImportant Dates:: The Nature and Operations of IASBMohamed DiabNo ratings yet

- AWS Dumps 1Document8 pagesAWS Dumps 1Krishna DarapureddyNo ratings yet

- Marine Casualty Report Final DraftDocument11 pagesMarine Casualty Report Final Draftapi-250839079No ratings yet

- 12.6% P.A. Quarterly Conditional Coupon With Memory Effect - European Barrier at 60% - 1 Year and 3 Months - EURDocument1 page12.6% P.A. Quarterly Conditional Coupon With Memory Effect - European Barrier at 60% - 1 Year and 3 Months - EURapi-25889552No ratings yet

- TIS Consultant Classification PDFDocument2 pagesTIS Consultant Classification PDFAbdullah Abdel-MaksoudNo ratings yet

- Criminology 1 ObeDocument6 pagesCriminology 1 ObeLove MadrilejosNo ratings yet

- Monthly Activity Report November 2020 of (ESDO-ICVGD)Document3 pagesMonthly Activity Report November 2020 of (ESDO-ICVGD)Razu Ahmed RazuNo ratings yet

- CM-S-004 I01 Composite Materials Shared Databases - KopieDocument9 pagesCM-S-004 I01 Composite Materials Shared Databases - KopieriversgardenNo ratings yet

- Regolamento Delegato (UE) 574 - 2014Document6 pagesRegolamento Delegato (UE) 574 - 2014c_passerino6572No ratings yet

- Civil War VocabDocument9 pagesCivil War Vocabapi-248111078No ratings yet

- In Re BalumaDocument1 pageIn Re BalumaCaitlin KintanarNo ratings yet

- Thermodynamics TestBank Chap 2Document13 pagesThermodynamics TestBank Chap 2Jay Desai100% (3)

- Shirkah, or Sharing, Can Exist As Shirkah Al-Milk, A Sharing of Ownership in A Property, orDocument2 pagesShirkah, or Sharing, Can Exist As Shirkah Al-Milk, A Sharing of Ownership in A Property, orSK LashariNo ratings yet

- Mmodule 5 Segment 1 Dispute ResolutionDocument3 pagesMmodule 5 Segment 1 Dispute ResolutionBALANGAT, Mc RhannelNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 14 06576 v2Document22 pagesSustainability 14 06576 v2Abdulbaset S AlbaourNo ratings yet

- The Cash Transactions and Cash Balances of Banner Inc ForDocument1 pageThe Cash Transactions and Cash Balances of Banner Inc Foramit raajNo ratings yet

- 53 Llorente v. CADocument2 pages53 Llorente v. CAGlenn Francis GacalNo ratings yet

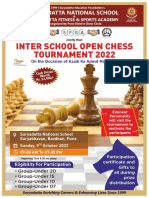

- Suryadatta-Chess Competition LeafletDocument2 pagesSuryadatta-Chess Competition LeafletabhishekdownloadNo ratings yet

- 26AS of BJZPK9513P-2023Document4 pages26AS of BJZPK9513P-2023Satheesh CharyNo ratings yet

- People V JalosjosDocument4 pagesPeople V JalosjosChad Osorio100% (2)

- The Federal Excise Act, 2005Document67 pagesThe Federal Excise Act, 2005Yogesh KumarNo ratings yet

- UsalistDocument4 pagesUsalistUmm ImraanNo ratings yet

- 1 Applicant Information SheetDocument4 pages1 Applicant Information Sheetharryjohn tianganNo ratings yet

- FranchisingDocument17 pagesFranchisingbench karl bautistaNo ratings yet

- IFRS - IAS19 - Employee BenefitsDocument16 pagesIFRS - IAS19 - Employee BenefitsPramita RoyNo ratings yet

- Annual Report - GVRIPL - 2014-15Document206 pagesAnnual Report - GVRIPL - 2014-15Rahul BarmechaNo ratings yet