Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Knowledge of God in Plantinga - Quodlibet Journal

Knowledge of God in Plantinga - Quodlibet Journal

Uploaded by

Emil BartosCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Knowledge of God in Plantinga - Quodlibet Journal

Knowledge of God in Plantinga - Quodlibet Journal

Uploaded by

Emil BartosCopyright:

Available Formats

Quodlibet Journal: Volume 4 Number 4, November 2002 http://www.Quodlibet.

net

Knowledge of God and Alvin Plantinga's Reformed Epistemology

Patrick J. Roche Plantinga, in a 1981 article, Reformed Objection to Natural Theology, made the claim - central to his account of Reformed epistemology - that argument or 'proof' is not required for the 'epistemic respectability' of belief in the existence of God. Plantinga's claim was that belief in God is 'properly basic' in the sense that the believer is within his 'epistemic rights' or not in beach of any 'epistemic obligations' in believing that God exists without inferential evidence or 'proof' from other beliefs such as the 'proofs' of natural theology. But in his 1981 article Plantinga also claimed that Calvin held that 'one who takes belief in God as basic (that is, without proof or inferential evidence) can nonetheless know that God exists'. [1] This raises the question of what is involved in the claim to know that God exists. Plantinga presented what he considered to be the 'correct picture' of knowledge in a 1982 article, On Reformed Epistemology: The correct picture of knowledge then goes as follows: a belief constitutes knowledge, if it is true, and if it arises as a result of the right use and proper function of our epistemic capacities. Of course this is only a picture, not a full-fledged account of knowledge [...] but I do think it is the right picture. [2] The 'picture' here is that the 'proper function' of belief-producing capacities/ mechanisms is what warrants true belief - that is, transforms true belief into knowledge. But what is involved in the notion of 'proper function'? The germ of Plantinga's account of 'proper function' is contained in the references in his early articles on Reformed epistemology to the 'triggering' mechanisms in terms of which he understood the production of basic beliefs. Plantinga's account of 'proper function' may be understood to give content to the bare notion of these 'triggering' mechanisms. Plantinga developed his account of 'proper function' in terms of the reliability of belief-producing mechanisms operating in an appropriate environment in accordance with a 'design plan' aimed at truth. [3] Plantinga incorporates an experiential dimension into the notion of 'proper function' to account for degree of warrant. Plantinga's position is that if a belief is warranted then for a properly functioning cognitive faculty the degree of warrant will be proportional to the degree of belief (or doxastic experience) associated with the belief in question. [4] Plantinga's developed account of warrant in Warrant and Proper Function does not require the performance of epistemic duty that figured in the evidentialism associated with classical foundationalism and indeed in Plantinga's understanding of justification/rationality in Reason and Belief in God and earlier articles on Reformed epistemology. [5] Plantinga's account of warrant in terms of 'proper function' marks a shift from the internalist understanding of epistemic propriety in terms of deontological requirement that was prominent in Reason and Belief in God. The understanding of warrant in terms of 'proper function' is distinctively externalist. On Plantinga's account of 'proper function' belief can have warrant even if the 'believer has no second-level beliefs at all about the beliefs in question' - that is, the believer 'need not have any well-formed ideas about the source or origin of the belief' for the belief in question to be warranted. [6] The externalism of Plantinga's developed account of warrant shifted the basis of Plantinga's understanding of epistemic propriety. Plantinga's early undeveloped references to the 'triggering' of the cognitive mechanisms that produce theistic belief ('God forgives me', etc) were combined with the understanding that theistic belief is epistemically grounded on religious experience. But Plantinga did not provide an intelligible account (or indeed any account at all) of the epistemic connection between the theistic beliefs and the religious experiences (minimally described in terms of 'sense' and 'feeling') on which the beliefs were understood by Plantinga to be grounded. [7]

But in any case, this internalist grounding of theistic belief on religious experience was replaced in Plantinga's developed account of warrant by an understanding of the epistemic propriety of theistic belief in terms of 'proper function'. This understanding is developed in Warranted Christian Belief in terms of what Plantinga designates the Aquinas/Calvin model (A/C model) involving the sensus divinitatis (the source of theistic belief) and the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit that is presented by Plantinga as the basis of warrant for specifically Christian belief. [8] The operation of the sensus divinitatis and of the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit is always accompanied by doxastic experience (integral to Plantinga's account of 'proper function') and in some instances by 'a sense of God being presented to our awarenress' involving 'awe' and a 'sense of the numinous'. [9] But this specifically religious experience does not accompany all the operations of the sensus divinitatis and the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit. [10] Plantinga seems somewhat hesitant about the contribution of religious experience to warrant within the framework of the A/C model set out in Warrant and Christian Belief. For example, Plantinga states that 'it isn't clear whether knowledge by way of the sensus divinitatis or the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit is properly thought of as knowledge by way of religious experience' [11] and 'it is dubious that knowledge by way of the sensus divinitatis and the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit, if there is any such knowledge, should be thought of as knowledge by experience'. [12] But the logic of Plantinga's account of warrant in terms of the A/C model is that theistic belief and specifically Christian belief are warranted by the 'proper function' of the sensus divinitatis and by the operation of the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit. Religious experience may occasion or accompany the operation of the A/C model (particularly in the case of the sensus divinatitus) but it is the 'proper function' of the sensus divinitatis or the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit that accounts for warrant. The logic of the A/C model is that warrant is divorced from religious experience because religious experience is not itself presented by Plantinga as determining or being essentially involved in the 'proper function' of the sensus divinitatis or in the operation of the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit. The proper function of the sensus divinitatis and the operation of the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit are presented by Plantinga in terms of an immediate/non-inferential awareness of the truth of theistic and specifically Christian belief. [13] Plantinga's account of the sensus divinitatis is based on the understanding that human beings are endowed with the cognitive capacity for a natural knowledge of God: The sensus divinitatis is a disposition or set of dispositions to form theistic beliefs in various circumstances, in response to the sorts of conditions or stimuli that trigger the working of this sense of divinity [...]. According to the model, therefore, there are many circumstances, and circumstances of many kinds (glories of nature, grave danger, awareness of divine disapproval, etc) that call forth or occasion theistic belief. Here the sensus divinitatis resembles other belief-producing faculties or mechanisms. If we wish to think in terms of the over-worked functional example, we can think of the sensus divinitatis too, as an input-output device: it takes the circumstances mentioned above as input and issues as output theistic beliefs, beliefs about God. [14] The extended A/C model developed by Plantinga in Warranted Christian Belief is an account of how specifically Christian belief (trinity, sin, incarnation, atonement, resurrection, eternal life) could be understood to have warrant. The model sets out a cognitive process leading to faith as the outcome of the 'internal testimony/ instigation of the Holy Spirit' to what Plantinga refers to as the 'great things of the gospel' contained in Scripture: Another part of God's response to our condition, however, is Scripture and the testimony of the Holy Spirit. God speaks to us in Scripture, teaching us his response to our fallen condition and the way in which this response is to be appropriated by us. By virtue of the inward instigation of the Holy Spirit we see that the teachings of Scripture are true. This work of the Holy Spirit, therefore, is a very special kind of cognitive instrument or agency; it is a belief-producing process, all right, but one that is very much out of the ordinary. It is not part of our original noetic equipment (not part of our

constitution as we came from the hand of the Maker), but instead part of a special divine response to our (unnatural) sinful condition. [15] The activity of the Holy Spirit as set out in the A/C model is understood to be required to overcome the noetic effects of sin - the activity of the Holy Spirit removes the 'cognitive blindness' [16] and restores the 'disordered affections' [17] of fallen human beings. The A/C model presents the work of the Holy Spirit as 'revealing to the mind' [18] and 'sealing on the heart' [19] the central doctrines of the gospel contained in Scripture. But Plantinga's understanding of Scripture in Warranted Christian Belief is somewhat ambiguous. There are repeated references to God as the 'author' of Scripture or the Bible [20] but at the same time Plantinga specifically argues that the belief that the Bible (the entire book) is authoritative for Christian belief and practice is not itself one of the 'great things of the gospel' - it is not an essential element of Christian belief. [21] These considerations suggest that Plantinga understands the internal testimony/instigation of the Holy Spirit to relate specifically to the scheme of salvation contained in Scripture. Faith is the outcome of this supernatural activity of the Holy Spirit. But on Plantinga's A/C model the propositional content of faith is confined to the 'central teaching of the gospel' [22] from which Plantinga excludes such propositions as 'the Gospel of John is from God' or the belief that 'God has inspired the New Testament in such a way that it is a communication from God to human beings'. [23] The final component of the A/C model is faith. How does Plantinga understand the nature of faith? Plantinga's basic position is that from the perspective of the A/C model faith is knowledge. But faith is knowledge of a special kind in terms both of its propositional content and how the knowledge is actually acquired by the supernatural activity of the Holy Spirit: So the propositional object of faith is the whole magnificent scheme of salvation God has arranged. To have faith is to know that and how God made it possible for us human beings to escape the ravages of sin and be restored to a right relationship with him; it is therefore a knowledge of the main lines of the Christian gospel. The content of faith is just the central teachings of the gospel; it is contained in the intersection of the great Christian creeds. [24] On Plantinga's account of knowledge the beliefs that constitute faith must be both warranted and true. But in terms of the A/C model these beliefs will be understood to be the output of a properly functioning belief-producing mechanism - the internal instigation/testimony of the Holy Spirit: The internal invitation of the Holy Spirit is therefore a source of belief, a cognitive process that produces in us belief in the main lines of the Christian story. Still further, according to the model, the beliefs thus produced in us meet the conditions necessary and sufficient for warrant; they are produced by cognitive processes functioning properly [...] according to a design plan successfully aimed at truth. [25] Plantinga considers that there is nothing problematic in applying the notion of 'proper function' to the supernatural belief-producing activity of the Holy Spirit as envisaged in the A/C model. [26] Faith, therefore, in terms of the A/C model will be understood to consist of warranted belief. Further, the A/C model is based on the presupposition that the supernatural belief-producing activity of the Holy Spirit is successfully aimed at the production of true beliefs. These considerations mean beliefs understood to result from the internal instigation/testimony of the Holy Spirit as envisaged in the A/C model will be understood to be both warranted and true and will therefore be understood to constitute knowledge. [27] The same considerations apply to the operation of the sensus divinitatis apart from the noetic effects of sin - hence Plantinga's claim the the sensus divinitatis is an original and natural source of knowledge of God but now impaired by the neotic effects of sin. [28] The beliefs produced by the sensus divinitatis (allowing for the noetic effects of sin) and by the internal instigation/testimony of the Holy Spirit are understood by Plantinga to be basic and

properly basic - that is, the beliefs are psychologically immediate and inferential reasoning is not required to establish the epistemic propriety of the beliefs in question. [29] Plantinga uses the visual metaphor of 'seeing' to convey what he considers to be cognitively involved in the internal instigation/testimony of the Holy Spirit. The metaphor of 'seeing' is used by Plantinga to convey the notion of a direct or immediate intuition or awareness of the truth of the propositional content of faith combined with a strong conviction or impulsion to believe: A principal work of the Holy Spirit with respect to us human beings is the production in us of the gift of faith, that 'firm and certain knowledge of God's benevolence towards us [...] both revealed to our mind and sealed upon our hearts through the Holy Spirit' of which Calvin speaks. By virtue of the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit we come to see the truth of the central Christian affirmations [...] The believer encounters the great truths of the gospel; by virtue of the activity of the Holy Spirit, she comes to see that these things are indeed true. [30] Plantinga's position is that the Holy Spirit provides an immediate (non-inferential) or intuitive awareness of the truth of the core beliefs of the Christian faith on the occasion of the believer reading or hearing or recollecting relevant portions of Scripture. Plantinga refers to a 'dual' belief-producing process involving both 'the divinely inspired Scripture (perhaps directly or perhaps at the head of a testimonial chain)' and the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit. [31] This understanding is related to Plantinga's account of the perspicuity of Scripture [32] and his understanding of the self-authenticating character of Scripture. [33] Plantinga claims that Scripture is perspicuous in the sense that the core teaching of Scripture (creation, sin, incarnation, atonement, resurrection, eternal life) can be understood and seen to be true by anyone of normal intelligence and ordinary training. The reason for this is that: There is available a source of warranted true belief, a way of coming to see the truth of these teachings that is quite independent of historical study: Scripture/internal instigation of the Holy Spirit/ faith (IIHS for short). By virtue of this process, an ordinary Christian, one quite innocent of historical studies, the ancient languages, the intricacies of textual criticism, the depths of theology and all the rest, can nevertheless come to know that these things are indeed true; furthermore, his knowledge need not trace back (by way of testimony for example) to knowledge on the part of someone who does have this specialised training. [34] Plantinga's claim here is not merely that the Holy Spirit provides an immediate understanding of the core doctrinal content of Scripture but that the Holy Spirit provides an immediate (noninferential) awareness or 'seeing' that the doctrines in question are actually true. The immediacy of this claimed awareness or 'seeing' of truth is such that it is achieved by the agency of the Holy Spirit in a manner that involves a 'revelation to the mind'. But the immediacy of this 'revelation to the mind' by the Holy Spirit is such that the internal testimony/instigation of the Holy Spirit occurs without reflection or inference involving historical, linguistic, textual or theological considerations on the part of the believer. That is how Plantinga presents the matter. This understanding of the perspicuity of Scripture is reinforced by Plantinga's account of what he claims to be the self-authenticating character of Scripture: What Calvin means then [...] is that we don't require argument from, for example, historically established premises about the authorship and reliability of the bit of Scripture in question to the conclusion that the bit in question is in fact true; that whole process gets short-circuited by way of the tripartite process (internal instigation of the Holy Spirit) producing faith. Scripture is self-authenticating in the sense that for belief in the great things of the gospel to be justified, rational and warranted no historical evidence and argument for the teaching in question, or for the veracity or reliability or divine character of Scripture (or the part of Scripture in which it is taught) are necessary. The process by which these beliefs have warrant for the believer swings free of those historical and other considerations; these beliefs have warrant in the basic way. [35]

Plantinga's account of the perspicuity of Scripture and the nature of Scripture as selfauthenticating is based on the understanding that the internal instigation/testimony of the Holy Spirit warrants belief in the doctrinal content of Scripture and provides an immediate awareness or 'seeing' of the truth of these doctrines. But the crucial point is that the claimed immediacy of this supernatural process is such that it 'swings free' (to use Plantinga's term) even of belief in the veracity or reliability or divine character of Scripture. [36] Plantinga's account of Scripture as perspicuous and self-authenticating is combined with an externalist account of warrant that does not require the believer to have 'any well-formed ideas about the source or origin' of belief. But this combination reduces belief to something like a dumb and passive 'awareness' unconnected to virtually everything that is required to render the beliefs in question ('the great things of the gospel') intelligible. [37] The determination of the truth of Christian belief (whatever that may require) cannot be understood (contrary to Plantinga) to involve a non-inferential awareness or 'revelation' divorced from biblical exegesis, conceptual formulation, historical investigation and presuppositions about the status of the Bible as revelation. The reason for this is that the doctrinal content of Scripture unpacks into a web and hierarchy of belief. The core doctrines of the Christian faith (trinity, incarnation, atonement, etc) are in fact highly interrelated and inferential constructions. This is well exemplified by the doctrinal content of the statement 'God was in Christ reconciling the world unto Himself' to which Plantinga makes frequent reference. The doctrinal content of this statement is inferentially constructed from an extensive range of other beliefs involving (for example) sophisticated and complex exegesis of Scripture. Further, beliefs such as 'God is angry with me' or 'God has forgiven my sins' are epistemically parasitic on the core doctrines of the Christian faith. The rationality or epistemic propriety for the Christian believer of the belief (for example) that 'God has forgiven my sins' is deeply embedded in biblical teaching on sin, repentance and forgiveness which in turn are deeply rooted in the biblical theology of the death and resurrection of Christ and in the Christian understanding of the moral character of God. The fact that a believer, who has assimilated even in a rudimentary manner the relevant biblical and creedal material, might on the occasion of reading 1 Corinthians 5 v 19 find himself spontaneously believing that doctrine is merely a commonplace psychological phenomenon without any epistemic significance certainly in terms of what would be required to establish the epistemic propriety of the belief in question. The implication of these considerations is that the notion that the core doctrines of the Christian faith (trinity, creation, fall, incarnation, atonement, resurrection, eternal life) could be understood (allowing for what the believer will recognise as an ultimate penumbra of mystery) in some immediate and non-inferential way - never mind the truth of these doctrines being discerned in this manner - simply does not make sense. Plantinga has attempted to squeeze an understanding of the epistemic propriety of Christian belief into a foundationalist mould. Plantinga's account of warrant is set within a foundationalist epistemology in which the core doctrines of the Christian faith are understood to be warranted in a manner that secures the proper basicality of these beliefs. Plantinga's foundationalist project is driven by the understanding that 'the Christian ought not to believe on the basis of argument; if he does his faith is likely to be unstable and wavering'. [38] Plantinga's position here seems to be that the epistemic stability of faith (belief in the 'great things of the Gospel') requires an account of warrant that secures the proper basicality of Christian belief. The proper basicality of Christian belief cannot be secured in terms of the requirements of classical foundationalism because Plantinga demonstrated that classical foundationalism is self-referentially incoherent. [39] But Plantinga retains the framework of foundationalism within which he develops a particularist account of the warrant of Christian belief directed towards securing the epistemic autonomy of Christian belief. Plantinga's account of the warrant of Christian belief is located within a metaphysical/ontological framework that in fact presupposes the existence of God and presupposes a theological understanding of the nature of the human person as a cognitive agent 'made in the image of God': [40]

What you properly take to be rational, at least in the sense of warranted depends on what sort of religious and metaphysical stance you adopt. It depends on what kinds of beings you think human beings are, what sorts of belief you think their noetic faculties will produce when they are functioning properly, and which of their faculties or cognitive mechanisms are aimed at truth. [41] Plantinga's position would seem to be that these metaphysical/ontological commitments determine the paradigm cases of properly basic belief that differentiate 'world-views' or more specific epistemic communities. This notion of differentiation does not exclude overlap in terms of what are accepted as paradigm cases of properly basic belief - for example, commonsense beliefs about physical objects, the past and the existence of other persons that are shared by both metaphysical naturalists and theists. But the paradigm cases of properly basic belief and the presuppositions on which their determination is based will at least intimate the types of belief that a properly functioning belief-producing capacity would be understood within a particular 'world-view' or epistemic community to produce in different circumstances/conditions. This may be illustrated by Plantinga's presentation of the distinction between a Freudian naturalist and a theist. The Freudian naturalist will believe that belief in God is not the output of a properly functioning truth-aimed cognitive faculty. [42] Plantinga's Reformed epistemologist will see the Freudian understanding of religious belief as due to the noetic effects of sin. [43] These diverse understandings of the content of 'proper function' in terms of the output of beliefs will at least implicitly contain criteria of proper basicality. The inductive method proposed by Plantinga in Reason and Belief in God may be understood as a procedure for making explicit (as far as that is possible) the criteria of proper basicality (or norms of epistemic propriety with respect to basic belief) implicit in the paradigm cases of properly basic belief that differentiate 'world-views' or more specifically differentiate theological traditions such as the Reformed tradition. Plantinga, in Reason and Belief in God, was operating with an internalist/deontological account of justification or epistemic propriety (understood in terms of epistemic right to believe) with respect to basic beliefs. The inductive method in Reason and Belief in God was set out by Plantinga in the context of a consideration of the determination of criteria of proper basicality with respect to prima facie justification understood in terms of a deontological right to believe. But when the inductive method is used in combination with an understanding of warrant in terms of 'proper function' the resulting norms/criteria of epistemic propriety will provide criteria for the type of circumstance/condition in which it is appropriate to consider that a particular belief is the output of a properly functioning belief-producing mechanism and is in consequent warranted. Distinct epistemic communities will have different criteria of proper basicality or different norms/criteria for warranted belief because the criteria/norms will result from the application of Plantinga's inductive method to the different sets of paradigm cases of properly basic belief that differentiate the epistemic communities in question. The Christian will of course suppose that belief in God is entirely proper and rational; if he does not accept this belief on the basis of other propositions, he will conclude that it is basic for him and quite properly so. Followers of Bertrand Russell [...] may disagree: but how is that relevant? Must my criteria or those of the Christian community conform to their examples? Surely not. The Christian community is responsible to its examples, not to theirs. [44] The implication of Plantinga's position is that the determination of criteria of proper basicality in terms of warrant and the determination of what is to count as knowledge is relative to the theological/ontological presuppositions that give content to the A/C models. Plantinga's Reformed epistemology is, therefore, distinctly relativistic. Plantinga's response to the 'Great Pumpkin objection' did not really engage with the issue of the relativistic import of his account of Reformed epistemology. The fact that the Reformed epistemologist understands belief in God to be properly basic does not commit the Reformed believer to accept just any belief as properly basic. [45] That is indeed the case. But that is not the issue and indeed the bizarre character of the 'Great Pumpkin' example may have had the unfortunate impact of rhetorically diffusing the relativistic import of Plantinga's Reformed epistemology.

The issue is whether Plantinga's particularist method is available to epistemic communities distinguished by (for example) non-theistic metaphysical/ontological presuppositions. The particularist/inductive method is available to such epistemic communities. The metaphysical/ontological presuppositions of distinct epistemic communities are epistemically permissible in terms of Plantinga's account of 'weak/deontological' justification. [46] For example, Plantinga states in Foundations of Theism that 'Calvinists, Moonies and Great Pumpkinites - all can follow my prescription'. [47] But if the metaphysical/ontological presuppositions that characterise distinct epistemic communities are used to give an account of proper basicality in terms of warrant (that is, to give content to models of 'proper function') the relativist import of Plantinga's epistemology extends to warrant and therefore to what is to count as knowledge. Plantinga's position is that distinct epistemic communities are deontologically justified with respect to their foundational metaphysical/ontological commitments. These presuppositional beliefs will shape each community's understanding of the nature of human beings as cognitive agents. This understanding will in turn determine or at least intimate the beliefs that distinct epistemic communities will regard as warranted or the output of a properly functioning beliefproducing mechanism: Relevant to the question of proper basicality, for example, is the question of what sorts of beings human beings are: what sorts of things will they believe when their faculties are functioning properly, are not subject to noetic defect or deficiency? Here Aquinas and Freud will have radically different views, and these differences may be reflected in their criteria for proper basicality. [48] Plantinga concedes in Warranted Christian Belief that there is a wide range of belief-systems within which models of warrant in terms of proper function could be given content. [49] Contrary to Plantinga, these belief-systems need not be theistic and certainly need not be 'seriously analogous to Christian belief'. [50] The notion of warrant in terms of proper function is compatible with the metaphysics of traditions within Hinduism and Buddhism that are not theistic in Plantinga's sense of the term. For example, Rose Ann Christian in a consideration of Plantinga's account of Reformed epistemology and metaphysical pluralism, draws attention to the fact that the Hindu understanding of the nature of the self means that it is rational for Hindu believers to take as basic the belief that through 'meditation' they experience union with Braham. Meditation, in this context may be understood in terms of Plantinga's epistemology as a mechanism or process to secure the proper functioning of religious cognitive capacity. These considerations mean that the notion of the 'proper function' of belief-producing capacity is compatible with the non-theistic metaphysics of the Hindu and Buddhist traditions to which Rose Ann Christian refers. [51] The account of warrant within Plantinga's Reformed epistemology gives content to the notion of the epistemic autonomy of belief-systems marked by radical metaphysical diversity. Despite these considerations Plantinga rejects the claim that his account of Reformed epistemology is 'fideistic'. But this is based on a presentation of the content of fideism (using a dictionary definition) that may not be relevant to fideism understood in terms of the 'epistemic autonomy' or 'epistemic particularism' of belief-systems or 'world-views'. [52] Plantinga's argument is that the 'Reformed epistemologist [...] is a fideist only if he holds that some central truths of Christianity are not among the deliverances of reason and must instead be taken on faith'. [53] Faith here is implicitly understood to be some (unspecified) basis of Christian belief other than the 'deliverances of reason'. But this raises the question as to what precisely is to count as a 'deliverance of reason'. Plantinga, in Reason and Belief in God, gives the following account: But just what are the deliverances of reason? What do they include? First, clearly enough, self-evident propositions and propositions that follow from them by selfevidently valid arguments are among the deliverances of reason. But we cannot stop there [....] The deliverances of reason [..] also include perceptual truths (propositions 'evident to the senses'), incorrigible propositions, certain memory propositions, certain propositions about other minds, and certain moral or ethical propositions [ ...] But what

about the belief that there is such a person as God and that we are responsible to him? Is that among the deliverances of reason or an item of faith? For Calvin it is clearly the former [...] Belief in the existence of God is in the same boat as belief in other minds, the past, and perceptual objects; in each case God has so constructed us that in the right circumstances we form the belief in question. But then the belief that there is such a person as God is as much among the deliverances of reason as those other beliefs. [54] This simply means that within the epistemic parameters of Reformed epistemology a 'deliverance of reason' will include beliefs produced by the sunsus divinitatis or by the internal instigation/invitation of the Holy Spirit - that is, by the belief-producing mechanisms of the A/C model. But these considerations mean that in the process of attempting to distance Reformed epistemology from an account of fideism based on a dictionary definition of the term, Plantinga in fact incorporates the very idea of what it is to count as a 'deliverance of reason' within the metaphysical and ontological commitments/presuppositions of the A/C model. This is a confirmation that 'fideism' understood in terms of the notion of 'epistemic autonomy' is central to Plantinga's account of Reformed epistemology. The fideistic/relativistic core of Plantinga's Reformed epistemology raises the issue of truth. Plantinga's developed account of what he designates Reformed epistemology is based on the understanding that warrant requires 'proper function' of belief-producing mechanisms. The notion of reliability is central to the notion of 'proper function'. Reliability is understood in terms of the non-accidental production of a high proportion of true beliefs. The core of Plantinga's account of warrant is that this non-accidental reliability requires the production of beliefs in accordance with a 'design plan'. Plantinga argues that this account of warrant in terms of 'proper function' cannot be coherently incorporated into the naturalistic metaphysics of the neoDarwinian theory of evolution. Basically, the reason is twofold. First, the notion of 'design plan' that Plantinga considers is required to account for non-accidental reliability does not (Plantinga believes) fit coherently into a naturalistic metaphysics. Second, neo-Darwinian evolution cannot account for/guarantee belief-producing mechanisms that are reliable in the sense of producing a high proportion of true beliefs. This second consideration is based on Plantinga's understanding that, within neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory, beliefs are epiphenomena in relation to the causality the produces adaptive behaviour. These considerations are the basis of Plantinga's understanding that metaphysical naturalism is false and indeed self-refuting. [56] But whatever the merits of Plantinga's arguments against metaphysical naturalism, his account of warrant is compatible with (and therefore capable of being incorporated into) a wide range of theistic and non-theistic belief systems. Plantinga mentions Judaism, Islam, some forms of Hinduism, some forms of Buddhism and some forms of American Indian religion in addition to Christianity. Adherents of these belief-systems could claim that the metaphysical/ontological presuppositions of these systems are prima facie/deontologically justified. The epistemologists of these religious traditions could use the presuppositional beliefs to specify models of warrant analogous to the A/C model: Are there any systems of beliefs seriously analogous to Christian belief for which these claims cannot be made? For any such set of beliefs, couldn't we find a model under which the beliefs in question have warrant, and such that, given the truth of these beliefs, there are no philosophical objections to the truth of the model? Well probably something like this is true for the other theistic religions. [57] Beliefs understood within these diverse metaphysical/religious traditions to be the proper output of the belief-producing mechanisms or 'models' would be regarded as warranted. The beliefsystems in question need not necessarily be theistic to accommodate the notion of 'proper function'. The epistemologists within these belief-systems might (like Plantinga) claim that the 'models' within their respective traditions provide a direct/non-inferential awareness or 'seeing' of the truth of beliefs understood to be the output of properly functioning belief-producing capacities.

Plantinga concedes that the account of the proper basicality of Christian belief in terms of the A/C model provides no apologetic leverage for Christian believers with respect to other beliefsystems. [58] The same consideration applies to the adherents of other religious/metaphysical traditions in relation to the Christian belief-system. This suggests that belief-systems that can accommodate Plantinga's account of warrant in terms of 'proper function' are on an epistemic par. The logic of Planting's Reformed epistemology is that there is no basis for the epistemic evaluation of competing belief-systems: Criteria for proper basicality arrived at in this particularistic way may not be polemically useful. If you and I start from different examples - if my set of examples includes a pair (where B is, say, belief in God and C is some condition) and your set of examples does not include - then we may well arrive at different criteria for proper basicality. Furthermore I cannot sensibly use my criterion to try to convince you that B is in fact properly basic in C, for you will point out, quite properly, that my criterion is based upon a set of examples that, as you see it, erroneously includes < B, C> as an example of a belief and condition such that the former is properly basic in the latter. You will be quite within your rights in claiming that my criterion is mistaken, although of course you may concede that, given my set of examples, I followed correct procedure in arriving at it. But of course by the same token you cannot sensibly use your criterion to try and convince me that B is not in fact properly basic in C. If criteria for proper basicality are arrived at in this particularistic way, they will not be or at any rate need not be polemically useful. Following this sort of procedure, we may not be able to resolve our disagreement as to the status of ; you will continue to hold that B is not properly basic in C, and I will continue to hold that it is. Of course it does not follow that there is no truth in the matter; if our criteria conflict, then at least one of them is mistaken even if we cannot by further discussion agree as to which it is. Similarly, either I am mistaken in holding that B is properly basic in C, or you are mistaken in holding that it is not. [59] The major competing truth claims of the belief-systems that could coherently incorporate Plantinga's account of warrant in terms of 'proper function' are mutually exclusive. For example, the monotheism of Islam and the trinitarianism of Christian belief are contradictory claims about the being of God. But Plantinga has a realist understanding of truth in opposition to what he takes to be the Rortyian position that truth is in some sense a human construct. [60] Plantinga understands truth in terms of the 'way things are': One of our most fundamental and basic ideas is that there is such a thing as the way things are. Now the existence of truth is intimately connected with there being a way things really are, a way the world is. [61] This is the basis of Plantinga's understanding that the de jure question (in terms of warrant) cannot be settled independently of the de facto question. There is a plurality of belief-systems that can coherently accommodate Plantinga's account of warrant in terms of 'proper function'. But whether the beliefs attributed to the relevant models (for example, the A/C model) are in fact warranted fundamentally depends on whether or not the metaphysical/ontological presuppositions of the relevant belief-systems are in fact true: And this dependence of the question of warrant or rationality on the truth or falsehood of theism leads to a very interesting conclusion. If the warrant enjoyed by belief in God is related in this way to the truth of that belief, then the question whether theistic belief has warrant is not, after all, independent of the question whether theistic belief is true. So the de jure question we have finally found is not, after all, really independent of the de facto question; to answer the former we must answer the latter. [62] But is it possible to determine (or 'show') the truth of the beliefs employed in specifying the A/C model? Plantinga's answer is unambiguous: I believe that the A/C models are not only possible [...] but also true. Still I don't claim to show that they are true. That is because the A/C model entails the truth of theism and the extended A/C model the truth of classical Christianity. To show that these models

are true [..] would also be to show that theism and Christianity are true; and I don't know how to do something one could sensibly call 'showing' that either of these is true. I believe that there are a large number of good arguments for the existence of God; none, however, can really be thought of as a showing or demonstration. As for classical Christianity, there is even less prospect of demonstrating its truth. [63] This does not fit easily with Plantinga's claim that the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit produces beliefs that 'are in fact true'. [64] But the crucial issue for Plantinga's account of Reformed epistemology is that if it is not possible to establish the truth of the A/C model then there is no reason to believe that the beliefs attributed to the sensus divinitatis and to the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit are in fact warranted. [65] Plantinga does not himself claim that these beliefs are warranted - for example, Plantinga states that 'this Reformed epistemologist (referring to himself) doesn't claim as part of his philosophical position that belief in God and the deliverances of the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit do have warrant'. [66] That, at least, is consistent with the conclusion of Warranted Christian Belief that 'it is beyond the competence of philosophy' [67] to show that Christian belief (specifically the presuppositions of the A/C model) are true. The implication of these considerations is that Plantinga's attempt to establish the warrant of Christian belief has in fact laid the basis of skepticism with respect to the warrant of Christian belief or indeed belief in general. [68] The skeptical import of Plantinga's Reformed epistemology with respect to the warrant of Christian belief is particularly troubling for commitment to traditional Christian belief because Plantinga's account of warrant undermines the soteriological exclusivism that is central to traditional Christian belief. Plantinga's Reformed epistemology does not terminate with skepticism with respect to the warrant for Christian belief. Truth is 'the way things are' but Plantinga's position is that it is beyond the competence of philosophy or any other competence to establish the truth of Christian belief. This leaves the Christian believer caught between the self-referential incoherence of classical foundationalism and the Rortyian understanding (as presented by Plantinga) of truth as a human construct - with no escape route in terms of a coherentist account of warrant. [69] In this situation Plantinga recommends a 'certain epistemic hardihood' taking the form of something like a Lutheran epistemic heroics: 'here I stand; this is the way the world looks to me'. [70] The import of this 'here I stand' position is that Plantinga's attempt to provide a warrant for Christian belief that would establish the foundationalist 'proper basicality' of Christian belief terminates, not merely in skepticism with respect to warrant, but in a radical subjectivism - that is, in irrationality on any definition of that term. These considerations mean that in Warranted Christian Belief Plantinga's project of 'Reformed epistemology' has not merely reached an epistemic 'dead-end' but has in fact been developed in a manner that undermines the credibility of the core exclusivist truth claims of the Christian tradition. Endnotes [1] Alvin Plantinga, The Reformed Objection to Natural Theology, Christian Scholar's Review, 1981, p. 19 [2] Alvin Plantinga, On Reformed Epistemology, The Reformed Journal, 32, January 1982, p.17 [3] Alvin Plantinga, Warrant and Proper Function, Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 46-47 [4 Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p.333 for the notion of 'doxastic experience' defined as 'the feeling, experience, intimation, with respect to a certain proposition that it is true, right, to be believed, the way things really are'. [5] See Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 178 where Plantinga states that 'this is the sense of proper basicality that was foremost in Reason and Belief in God' and 'that sense was foremost there because there I was contesting the views of the evidentialist objectors to theistic belief [...] they understood justification and the lack of

justification in deontological terms: to be unjustified is to be epistemically irresponsible, to flout an epistemic duty or requirement of some sort'. [6] Alvin Plantinga, op. cit.,p.179 [7] Alvin Plantinga, Reason and Belief in God in Alvin Plantinga and Nicholas Wolterstroff, Faith and Philosophy, University of Notre Dame Press, 1986, p.80-81. [8] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 168. See also Plantinga's account of a 'model'. [9] Ibid, p. 182. [10] Ibid, p.182. [11] Ibid, p.336 [12] Ibid, p.337 [13] Ibid, p.175 for the sensus divinitatis and p.251 for the internal instigation of the Holy Spirit. See also p.378. [14] Ibid, p.173-75, p.199. [15] Ibid, p.180 [16] Ibid, p.207 [17] Ibid, p.207 [18] Ibid, p.244, p.256, p.269 [19] Ibid, p.244, p.267 [20] Ibid, p.181, 243, 324, 375, 381-83, 385, 399, 401. [21] Ibid, p.376 [22] Ibid, p.248 [23] Ibid, p.380 and p.248, 260, 376 [24] Ibid, p.248, 256 [25] Ibid, p.248 [26] Ibid, p.257-58 [27] Ibid, p.256, p.258 [28] Ibid, p.175, p.214, p. 217 [29] Ibid, p.250, 259, 378 [30] Ibid, p.206, 256, 252

[31] Ibid, p.250, 256 [32] Ibid, p.374. But see pp. 381-83 for a more qualified view of the perspicuity of Scripture. [33] Ibid, p.259-62 [34] Ibid, p.374, 381 [35] Ibid, p.262, 378 [36] Ibid, p.259 [37] See Laurence Bonjour, Plantinga on Knowledge and Proper Function in Jonathan L. Kvanvig (ed), Warrant in Contemporary Epistemology: Essays in Honour of Plantinga's Theory of Knowledge, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 1996. Bonjour refers to Sosa's distinction between 'animal knowledge' and 'reflective knowledge' where the latter 'involves a wider understanding of how the belief came about and how it is related to the fact that is its object [...] reflective knowledge essentially involves an internal dimension of critical reflection' (p.60). Bonjour argues that Plantinga's account of warrant and the conception of knowledge that results from it 'capture at best some close approximation to animal knowledge, not the reflective knowledge that is distinctively human' (p.60). [38] Alvin Plantinga, The Reformed Objection to Natural Theology, Christian Scholar's Review, 1981, p.190 and Alvin Plantinga, Reason and Belief in God, op. cit., p.67, 72, 73 [39] Alvin Plantinga, Reason and Belief in God, op. cit., p.59-63 [40] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 204 [41] Ibid, p. 190. See also Alvin Plantinga, Theism, Atheism and Rationality, Truth: A Journal of Modern Thought, Year, Page. and The Prospects for Natural Theology, in James Tomberlin (ed), Philosophical Perspectives, 5:Philosophy of Religion, Ridgeview Publishing Co, p.309. [42] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p.151 [43] Ibid, p.198 [44] Alvin Plantinga, Reason and Belief in God, op. cit., p.76 [45] Ibid, p.74 [46] Ibid, p.85 for Plantinga's distinction between 'weak' and 'strong' justification. Se also Warranted Christian Belief, p. 203, 178 and p. 100-02 [47] Alvin Plantinga, The Foundations of Theism: A Reply, Faith and Philosophy, Vol. 3, No 5, July 1986, p. 302. [48] Ibid, p.303 [49] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p.351 [50] Ibid, p.351 [51] Rose Ann Christian, Plantinga, Epistemic Permissiveness and Metaphysical Pluralism, Religious Studies, 28, 1992, p. 568-69

[52] C Stephan Evans, Faith Beyond Reason, Edinburgh University Press, 1998, p. 24, p. 45-47 [53] Alvin Plantinga, Reason and Belief in God, op cit., p.89 [54] Ibid, pp. 89-90 [55] Alvin Plantinga, Warrant and Proper Function, Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 17 [56] Alvin Plantinga, Warrant and Proper Function, Oxford University Press, 1993, chapters 1112 and Alvin Plantinga, An Evolutionary Case Against Naturalism, Religious and Theological Studies Fellowship Bulletin, March 1996. [57] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p.350 [58] Alvin Plantinga, Reason and Belief in God, op. cit., p. 78 and see also Dirk-Martin Grube, Religious Experience after the Demise of Foundationalism, Religious Studies, 31, 1995, p.43. [59] Alvin Plantinga, op. cit., pp.77-78 [60] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 429-36 [61] Ibid, p.191 [62] Ibid, p. 191 [63] Ibid, pp. 169-70 [64] Ibid, p.257 [65] See Laurence Bonjour, op. cit., p.63 for basically the same point made as a general observation on Plantinga's account of warrant. Bonjour states that 'the crucial factor in warrant, viz, the cognitive design plan, is not something that we even have any very specific beliefs about, making it difficult to see how we could possibly have any good reason for thinking that the specific conditions required for warrant are satisfied'. [66] Alvin Plantinga op. cit., p. 347 [67] Ibid, p. 499 [68] Ibid, Laurence Bonjour, op. cit., p. 63 [69] See Alvin Plantinga, Coherentism and the Evidential Objection to Belief in God, in Robert Audi and W. J. Wainwright, (eds), Rationality, Religious Belief and Moral Commitment, 1986 [70] Alvin Plantinga, Warranted Christian Belief, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 436-37 Patrick J. Roche Tutor in Philosophy of Religion Irish Baptist College, 67 Sandown Road, Belfast, BT5 6GU, Northern Ireland

You might also like

- Dietrich of Freiberg - de Visione BeatificaDocument90 pagesDietrich of Freiberg - de Visione BeatificaSahrian100% (2)

- David Braine The Reality of Time and The Existence of GodDocument5 pagesDavid Braine The Reality of Time and The Existence of GodAnders LOpézNo ratings yet

- Many are strong among the strangers: Canadian songs of immigrationFrom EverandMany are strong among the strangers: Canadian songs of immigrationNo ratings yet

- Aquinas, On LibertyDocument19 pagesAquinas, On LibertynatzucowNo ratings yet

- MGT502 MCQs Solved 1 Attitudes and Job SatisfactionDocument7 pagesMGT502 MCQs Solved 1 Attitudes and Job Satisfactionamrin jannat100% (1)

- A Pattern For The ChurchDocument4 pagesA Pattern For The Churchapi-86744070No ratings yet

- God's Mind For The NT ChurchDocument14 pagesGod's Mind For The NT ChurchDavid A. DePraNo ratings yet

- Stigmata IsLucyRael ForReal PDFDocument4 pagesStigmata IsLucyRael ForReal PDFPrince McGershonNo ratings yet

- The Hundred FoldDocument4 pagesThe Hundred FoldTMOT - The Message of TransfigurationNo ratings yet

- Behold Wrath Internal PREVIEWDocument70 pagesBehold Wrath Internal PREVIEWDavid ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- No More Sin Against The BodyDocument16 pagesNo More Sin Against The BodyTMOT - The Message of TransfigurationNo ratings yet

- Free Will and PredestinationDocument5 pagesFree Will and PredestinationAdamNo ratings yet

- New Testament EthicsDocument5 pagesNew Testament EthicsCHARMAINE JOY NATIVIDADNo ratings yet

- Research Methods in Health and Social Care AssignmentDocument3 pagesResearch Methods in Health and Social Care AssignmentPamoda Madurapperuma0% (1)

- Cosmic Christianity Part2Document42 pagesCosmic Christianity Part2Remus BabeuNo ratings yet

- Think on Your Thoughts Volume Ii: The Act Accordingly SeriesFrom EverandThink on Your Thoughts Volume Ii: The Act Accordingly SeriesNo ratings yet

- 1994 Issue 1 - Book Review: Calvin's Preaching by T.H.L. Parker - Counsel of ChalcedonDocument9 pages1994 Issue 1 - Book Review: Calvin's Preaching by T.H.L. Parker - Counsel of ChalcedonChalcedon Presbyterian ChurchNo ratings yet

- 2001 Spring EpistemologyDocument33 pages2001 Spring EpistemologyLalpu HangsingNo ratings yet

- FaithDocument9 pagesFaithAlua NurpeissovaNo ratings yet

- Religious Experience and The Facts of Religious Pluralism (DAVID SILVER) (2001)Document18 pagesReligious Experience and The Facts of Religious Pluralism (DAVID SILVER) (2001)saulNo ratings yet

- Faith Without Reasons - A Review of Warranted Christian Belief by Alvin PlantingaDocument10 pagesFaith Without Reasons - A Review of Warranted Christian Belief by Alvin PlantingaEmil BartosNo ratings yet

- Chapter II (Baldwin)Document9 pagesChapter II (Baldwin)Miguel Aguilar AguilarNo ratings yet

- Plantinga's Reformed Epistemology, Evidentialism, and Evangelical ApologeticsDocument22 pagesPlantinga's Reformed Epistemology, Evidentialism, and Evangelical ApologeticsBruno Ribeiro NascimentoNo ratings yet

- God God God: I. The Meaning of The WordDocument17 pagesGod God God: I. The Meaning of The WordQuo PrimumNo ratings yet

- A Philosopher Defends ReligionDocument7 pagesA Philosopher Defends ReligionzizekNo ratings yet

- Epistemology of Religion (Notes)Document3 pagesEpistemology of Religion (Notes)Rizwan 'Rizziano' BandaliNo ratings yet

- Huett Ert I Retreat Talk 1 FaithDocument17 pagesHuett Ert I Retreat Talk 1 FaithAbNo ratings yet

- An Islamic Account of Reformed Epistemology DraftUploadDocument24 pagesAn Islamic Account of Reformed Epistemology DraftUploadSiyovush MNo ratings yet

- Faith and Rationality Plantinga PDFDocument1 pageFaith and Rationality Plantinga PDFTrevorNo ratings yet

- Faith and ReasonDocument3 pagesFaith and ReasonGabrielAmobiNo ratings yet

- Integration Yakob SusabdaDocument13 pagesIntegration Yakob SusabdaJosue FamaNo ratings yet

- Warfield, BB by Helseth On ApologeticsDocument11 pagesWarfield, BB by Helseth On ApologeticsStephen HagueNo ratings yet

- Faith A Gift BenDocument9 pagesFaith A Gift Ben9460No ratings yet

- Insti Lesson 5Document2 pagesInsti Lesson 5bevienlynpepito10No ratings yet

- Obedience Before UnderstandingDocument20 pagesObedience Before UnderstandingJohn BrodeurNo ratings yet

- Has Ker 1998Document16 pagesHas Ker 1998Yolanda LiNo ratings yet

- Aquinas Faith ReasonDocument4 pagesAquinas Faith Reasonaltereudaimonia100% (1)

- What Is The Nature of Saving Faith?: Steve Lewis, M.A., M.DivDocument13 pagesWhat Is The Nature of Saving Faith?: Steve Lewis, M.A., M.Divsoewintaung sarakabaNo ratings yet

- Carried Through the Valley: Transformed by Christ Through LamentFrom EverandCarried Through the Valley: Transformed by Christ Through LamentNo ratings yet

- Calvin's Theology of The Holy SpiritDocument3 pagesCalvin's Theology of The Holy SpiritOli65No ratings yet

- Aquinas Philosophical TheologyDocument20 pagesAquinas Philosophical TheologyMa. Kyla Wayne LacasandileNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Lesson 4Document7 pagesUnit 2 Lesson 4Rhea BadanaNo ratings yet

- The Gospel Coalition Blog Reason For Your Hope - Scott Oliphint On A Fresh Approach PrintDocument3 pagesThe Gospel Coalition Blog Reason For Your Hope - Scott Oliphint On A Fresh Approach Printl1o2stNo ratings yet

- Theology - Faith (Pananampalataya)Document10 pagesTheology - Faith (Pananampalataya)John Ray BacaniNo ratings yet

- On The Pragmatist View of FaithDocument7 pagesOn The Pragmatist View of FaithAnonymous qZsxBMNo ratings yet

- Triune God 4Document14 pagesTriune God 4Michael AllenNo ratings yet

- Nagel's Review of Platinga's BookDocument8 pagesNagel's Review of Platinga's BookSpyrtou Spyrtou100% (1)

- From Theology To Philosophy in The Latin WestDocument14 pagesFrom Theology To Philosophy in The Latin WestSoponaru StefanNo ratings yet

- Jermaine Preston - Part 1 B Marked and GradedDocument4 pagesJermaine Preston - Part 1 B Marked and GradedrhonellapaulNo ratings yet

- The Nature of The New Birth: Preview and Compact SummaryDocument13 pagesThe Nature of The New Birth: Preview and Compact SummaryChristopher PepplerNo ratings yet

- Plantinga Kant and Cognitive ReliabilityDocument9 pagesPlantinga Kant and Cognitive Reliabilitynovan gebbyanoNo ratings yet

- Not Classic Al, CovenantalDocument22 pagesNot Classic Al, CovenantalIvanNo ratings yet

- Without Absolutes, God Is Not God: An Anthology of ReflectionsFrom EverandWithout Absolutes, God Is Not God: An Anthology of ReflectionsNo ratings yet

- 2002-Alvin PlantingaDocument1 page2002-Alvin Plantingadr_william_sweetNo ratings yet

- The Divine Energies in The New TestamentDocument24 pagesThe Divine Energies in The New TestamentDiorNo ratings yet

- The Primacy of Intellection by Frithjof SchuonDocument5 pagesThe Primacy of Intellection by Frithjof SchuonCaio CardosoNo ratings yet

- The Holy Spirit as Communion: Colin Gunton’s Pneumatology of Communion and Frank Macchia’s Pneumatology of KoinoniaFrom EverandThe Holy Spirit as Communion: Colin Gunton’s Pneumatology of Communion and Frank Macchia’s Pneumatology of KoinoniaNo ratings yet

- A Chronology of Acts - McGough PDFDocument13 pagesA Chronology of Acts - McGough PDFEmil Bartos100% (1)

- Making Sense of Suffering and Death - O'MalleyDocument6 pagesMaking Sense of Suffering and Death - O'MalleyEmil BartosNo ratings yet

- Apologetics - Article - The Twilight of Atheism. Smith Lecture 2006 - Allister Mc. GrathDocument8 pagesApologetics - Article - The Twilight of Atheism. Smith Lecture 2006 - Allister Mc. GrathEmil Bartos100% (1)

- Apologetics - Article - Marriage Tending Mending Ending - Tina Beattie, University of Cork, Friday, 17 NovemberDocument17 pagesApologetics - Article - Marriage Tending Mending Ending - Tina Beattie, University of Cork, Friday, 17 NovemberEmil BartosNo ratings yet

- Guthrie, Shirley - Human Suffering, Human Liberation, and The Sovereignty of GodDocument13 pagesGuthrie, Shirley - Human Suffering, Human Liberation, and The Sovereignty of GodEmil BartosNo ratings yet

- Apologetics - Article - Film Review Da Vinci Code - Tina Beattie, The Tablet, 20 May 2006Document2 pagesApologetics - Article - Film Review Da Vinci Code - Tina Beattie, The Tablet, 20 May 2006Emil BartosNo ratings yet

- Apologetics - Darwinism and Christianity. Must They Remain at War or Is Peace Possible - MichaelDocument19 pagesApologetics - Darwinism and Christianity. Must They Remain at War or Is Peace Possible - MichaelEmil BartosNo ratings yet

- Apologetics - Ars Disputandi - An Incomplete Diagnosis. John Dewey and Problem of Evil - Alan G. Phillips, JR., Vol. 7, 2007Document4 pagesApologetics - Ars Disputandi - An Incomplete Diagnosis. John Dewey and Problem of Evil - Alan G. Phillips, JR., Vol. 7, 2007Emil BartosNo ratings yet

- Faith Without Reasons - A Review of Warranted Christian Belief by Alvin PlantingaDocument10 pagesFaith Without Reasons - A Review of Warranted Christian Belief by Alvin PlantingaEmil BartosNo ratings yet

- Apologetics - Ars Disputandi - A Deontological Solution To The Problem of Evil - Albert Haig, Vol. 6, 2006Document10 pagesApologetics - Ars Disputandi - A Deontological Solution To The Problem of Evil - Albert Haig, Vol. 6, 2006Emil BartosNo ratings yet

- SUBJEKT Kierkegaard PDFDocument3 pagesSUBJEKT Kierkegaard PDFJeppe Sophus LaiNo ratings yet

- 10 Ethos Pathos Logos ReviewDocument18 pages10 Ethos Pathos Logos ReviewBradley BesterNo ratings yet

- Descartes - Mind-Body DualismDocument5 pagesDescartes - Mind-Body Dualismapi-317334105No ratings yet

- SocratesDocument3 pagesSocratesBenitez Gherold0% (1)

- CBSE Worksheets For Class 12 Psychology AssignmentDocument2 pagesCBSE Worksheets For Class 12 Psychology Assignmentrakhee mehtaNo ratings yet

- Kant EssayDocument14 pagesKant EssaylastliamNo ratings yet

- How Can Knowing Oneself Make Someone A Better PersonDocument2 pagesHow Can Knowing Oneself Make Someone A Better PersonArnie AndreoNo ratings yet

- (Saul McLeod) Cognitive-Dissonance ArticleDocument6 pages(Saul McLeod) Cognitive-Dissonance ArticleJohn ReyesNo ratings yet

- Oneness and Manyness Buddhist Causality-WooDocument7 pagesOneness and Manyness Buddhist Causality-Wootamodeb2No ratings yet

- John Dewey - Concept of Man and Goals of Education PreviewDocument2 pagesJohn Dewey - Concept of Man and Goals of Education Previewsalim6943No ratings yet

- Socrates ContemporaryDocument2 pagesSocrates ContemporaryMaru Mandale Dator PerezNo ratings yet

- IB TOK Essay - "'Through Different Methods of Justification, We Can Reach Conclusions in Ethics That Are As Well-Supported As Those Provided in Mathematics.' To What Extent Would You Agree?"Document6 pagesIB TOK Essay - "'Through Different Methods of Justification, We Can Reach Conclusions in Ethics That Are As Well-Supported As Those Provided in Mathematics.' To What Extent Would You Agree?"Marc WierzbitzkiNo ratings yet

- Consumer Attitude Formation and Change: Consumer Behavior, Eighth EditionDocument35 pagesConsumer Attitude Formation and Change: Consumer Behavior, Eighth Editionjugnu4selfNo ratings yet

- 2 - Perception and Individual Decision MakingDocument11 pages2 - Perception and Individual Decision Makingmorty000No ratings yet

- (Psych) Fowler's Spiritual Development TheoryDocument13 pages(Psych) Fowler's Spiritual Development TheoryEvan Larona50% (2)

- Philosophy of MindDocument17 pagesPhilosophy of Mindhemanthnaidu.d100% (1)

- What Is PhilosophyDocument3 pagesWhat Is PhilosophyAries TembliqueNo ratings yet

- Lee Carey 2013 - EWB-libreDocument10 pagesLee Carey 2013 - EWB-libreViorelNo ratings yet

- Self Perceived Objectivity On Hiring Discrimination Uhlmann and Cohen 2007 PDFDocument17 pagesSelf Perceived Objectivity On Hiring Discrimination Uhlmann and Cohen 2007 PDFAnaGarciaNo ratings yet

- Criticisms of The CogitoDocument8 pagesCriticisms of The Cogitomaria_meNo ratings yet

- Dialogues With DavidsonDocument508 pagesDialogues With Davidsonsaeedgaga100% (3)

- Robert Ellwood - Review of Forgotten TruthDocument1 pageRobert Ellwood - Review of Forgotten TruthdesmontesNo ratings yet

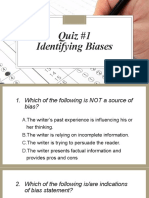

- Quiz 1 - Identifying BiasesDocument17 pagesQuiz 1 - Identifying BiasesRigor Suguitao100% (1)

- Stereotyping: Blaine CH 2 & 3Document11 pagesStereotyping: Blaine CH 2 & 3MohabbatRJNo ratings yet

- Absensi Sholat Jum at XII C 1Document20 pagesAbsensi Sholat Jum at XII C 1Sun ToroNo ratings yet

- 2 Ethical TheoriesDocument34 pages2 Ethical Theoriesrar93No ratings yet

- Chapter 14: Social PsychologyDocument78 pagesChapter 14: Social PsychologyMayer AdelmanNo ratings yet

- Externalist Theories of Empirical Knowledge PDFDocument2 pagesExternalist Theories of Empirical Knowledge PDFSteveNo ratings yet