Professional Documents

Culture Documents

M A Material

M A Material

Uploaded by

Ganga DharaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

M A Material

M A Material

Uploaded by

Ganga DharaCopyright:

Available Formats

Richard II Richard II, written around 1595, is the first play in Shakespeare's second "history tetralogy," a series of four

plays that chronicles the rise of the house of Lancaster to the British throne. (Its sequel plays are Henry IV, Parts 1 & 2, and Henry V.) Richard II, set around the year 1398, traces the fall from power of the last king of the house of Plantagenet, Richard II, and his replacement by the first Lancaster king, Henry IV (Henry Bolingbroke). Richard II, who ascended to the throne as a young man, is a regal and stately figure, but he is wasteful in his spending habits, unwise in his choice of counselors, and detached from his country and its common people. He spends too much of his time pursuing the latest Italian fashions, spending money on his close friends, and raising taxes to fund his pet wars in Ireland and elsewhere. When he begins to "rent out" parcels of English land to certain wealthy noblemen in order to raise funds for one of his wars, and seizes the lands and money of a recently deceased and much respected uncle to help fill his coffers, both the commoners and the king's noblemen decide that Richard has gone too far. Richard has a cousin, named Henry Bolingbroke, who is a great favorite among the English commoners. Early in the play, Richard exiles him from England for six years due to an unresolved dispute over an earlier political murder. The dead uncle whose lands Richard seizes was the father of Bolingbroke; when Bolingbroke learns that Richard has stolen what should have been his inheritance, it is the straw that breaks the camel's back. When Richard unwisely departs to pursue a war in Ireland, Bolingbroke assembles an army and invades the north coast of England in his absence. The commoners, fond of Bolingbroke and angry at Richard's mismanagement of the country, welcome his invasion and join his forces. One by one, Richard's allies in the nobility desert him and defect to Bolingbroke's side as Bolingbroke marches through England. By the time Richard returns from Ireland, he has already lost his grasp on his country. There is never an actual battle; instead, Bolingbroke peacefully takes Richard prisoner in Wales and brings him back to London, where Bolingbroke is crowned King Henry IV. Richard is imprisoned in the remote castle of Pomfret in the north of England, where he is left to ruminate upon his downfall. There, an assassin, who both is and is not acting upon King Henry's ambivalent wishes for Richard's expedient death, murders the former king. King Henry hypocritically repudiates the murderer and vows to journey to Jerusalem to cleanse himself of his part in Richard's death. As the play concludes, we see that the reign of the new King Henry IV has started off inauspiciously. The History Plays The "history plays" written by Shakespeare are generally thought of as a distinct genre: they differ somewhat in tone, form and focus from his other plays (the "comedies," the "tragedies" and the "romances"). While many of Shakespeare's other plays are set in the historical past, and even treat similar themes such as kingship and revolution (for example, Julius Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, Hamlet, or Cymbeline), the eight history plays have several things in common: they form a linked series, they are set in late medieval England, and they deal with the rise and fall of the House of Lancaster--what later historians often referred to as the "War of the Roses." Shakespeare's most important history plays were written in two "series" of four plays. The first series, written near the start of his career (around 1589-1593), consists of Henry VI, Parts 1, 2 & 3, and Richard III, and covers the fall of the Lancaster dynasty--that is, events in English history between about 1422 and 1485. The second series, written at the height of Shakespeare's powers (around 1595-1599), moves back in time to examine the rise of the Lancastrians, covering English history from about 1398 to 1420. This series consists of Richard II, Henry IV, Parts 1 & 2, and Henry V. Although the events he writes about occurred some two centuries before his own time, Shakespeare expected his audience to be familiar with the characters and events he was describing. The battles among houses and the rise and fall of kings were woven closely into the fabric of English culture and formed an integral part of the country's patriotic legends and national mythology. This might be compared to the way in which citizens of the United States are still aware of the events and figures surrounding the American Revolution, which occurred more than two centuries ago--although, like the English commoners of Shakespeare's time, most American do not know this history in great detail. Shakespearean history is thus often inaccurate in its details, but it reflects popular conceptions of history. Shakespeare drew on a number of different sources in writing his history plays. His primary source for historical material, however, is generally agreed to be Raphael Holinshed's massive work, The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, published in 1586-7. Holinshed's account provides the chronology of events that Shakespeare reproduces, alters, compresses, or conveniently avoids--whichever serves his dramatic purposes best. However, Holinshed's work was only one of an entire genre of historical chronicles that were popular during Shakespeare's time. He may well have used many other sources as well; for Richard II, for example, more than seven primary sources have been suggested as having contributed to the work. It is important to remember, when reading the history plays, the significance to this genre of what we might call the "shadows of history." One of the questions which preoccupies the characters in the history plays is whether or not the King of England is divinely appointed by the Lord. If so, then the overthrow or murder of a king is tantamount to blasphemy, and may cast a long shadow over the reign of the king who gains the throne through such nefarious means. This shadow, which manifests in the form of literal ghosts in plays like Hamlet, Macbeth, Julius Caesar, and Richard III, also looms over Richard II and its sequels. The murder of the former King Richard II at the end of Richard II will haunt King Henry IV for the rest of his life, and the curse can only be redeemed by his son, Henry V. Similarly, Richard II himself, in the play which bears his name, is haunted by a politically motivated murder: not of a king, but of his uncle, Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester. This death occurs long before the beginning of the play, but, as we will see, it haunts Richard, just as his own death will haunt the usurper who is responsible for it. Doctor Faustus Doctor Faustus, a well-respected German scholar, grows dissatisfied with the limits of traditional forms of knowledgelogic, medicine, law, and religionand decides that he wants to learn to practice magic. His friends Valdes and Cornelius instruct him in the black arts, and he begins his new career as a magician by summoning up Mephastophilis, a devil. Despite Mephastophiliss warnings about the horrors of hell, Faustus tells the devil to return to his master, Lucifer, with an offer of Faustuss soul in exchange for twenty-four years of service from Mephastophilis. Meanwhile, Wagner, Faustuss servant, has picked up some magical ability and uses it to press a clown named Robin into his service. Mephastophilis returns to Faustus with word that Lucifer has accepted Faustuss offer. Faustus experiences some misgivings and wonders if he should repent and save his soul; in the end, though, he agrees to the deal, signing it with his blood. As soon as he does so, the words Homo fuge, Latin for O man, fly, appear branded on his arm. Faustus again has second thoughts, but Mephastophilis bestows rich gifts on him and gives him a book of spells to learn. Later, Mephastophilis answers all of his questions about the nature of the world, refusing to answer only when Faustus asks him who made the universe. This refusal prompts yet another bout of misgivings in Faustus, but

Mephastophilis and Lucifer bring in personifications of the Seven Deadly Sins to prance about in front of Faustus, and he is impressed enough to quiet his doubts. Armed with his new powers and attended by Mephastophilis, Faustus begins to travel. He goes to the popes court in Rome, makes himself invisible, and plays a series of tricks. He disrupts the popes banquet by stealing food and boxing the popes ears. Following this incident, he travels through the courts of Europe, with his fame spreading as he goes. Eventually, he is invited to the court of the German emperor, Charles V (the enemy of the pope), who asks Faustus to allow him to see Alexander the Great, the famed fourth-century b.c. Macedonian king and conqueror. Faustus conjures up an image of Alexander, and Charles is suitably impressed. A knight scoffs at Faustuss powers, and Faustus chastises him by making antlers sprout from his head. Furious, the knight vows revenge. Meanwhile, Robin, Wagners clown, has picked up some magic on his own, and with his fellow stablehand, Rafe, he undergoes a number of comic misadventures. At one point, he manages to summon Mephastophilis, who threatens to turn Robin and Rafe into animals (or perhaps even does transform them; the text isnt clear) to punish them for their foolishness. Faustus then goes on with his travels, playing a trick on a horse-courser along the way. Faustus sells him a horse that turns into a heap of straw when ridden into a river. Eventually, Faustus is invited to the court of the Duke of Vanholt, where he performs various feats. The horsecourser shows up there, along with Robin, a man named Dick (Rafe in the A text), and various others who have fallen victim to Faustuss trickery. But Faustus casts spells on them and sends them on their way, to the amusement of the duke and duchess. As the twenty-four years of his deal with Lucifer come to a close, Faustus begins to dread his impending death. He has Mephastophilis call up Helen of Troy, the famous beauty from the ancient world, and uses her presence to impress a group of scholars. An old man urges Faustus to repent, but Faustus drives him away. Faustus summons Helen again and exclaims rapturously about her beauty. But time is growing short. Faustus tells the scholars about his pact, and they are horror-stricken and resolve to pray for him. On the final night before the expiration of the twenty-four years, Faustus is overcome by fear and remorse. He begs for mercy, but it is too late. At midnight, a host of devils appears and carries his soul off to hell. In the morning, the scholars find Faustuss limbs and decide to hold a funeral for him. The Way of theWorld The play is based around the two lovers Mirabell and Millamant (originally famously played by John Verbruggen and Anne Bracegirdle). In order for the two to get married and receive Millamant's full dowry, Mirabell must receive the blessing of Millamant's aunt, Lady Wishfort. Unfortunately, she is a very bitter lady, who despises Mirabell and wants her own nephew, Sir Wilful, to wed Millamant. Other characters include Fainall who is having a secret affair with Mrs. Marwood, a friend of Mrs. Fainall's, who in turn once had an affair with Mirabell. Waitwell is Mirabell's servant and is married to Foible, Lady Wishfort's servant. Waitwell pretends to be Sir Rowland and, on Mirabell's command, tries to trick Lady Wishfort into a false engagement. William Congreve's The Way of the World is the best-written, the most dazzling, the most intellectually accomplished of all English comedies, perhaps of all the comedies of the world. But it has the defects of the very qualities which make it so brilliant. A perfect comedy does not sparkle so much, is not so exquisitely written, because it needs to advance, to develop. To The Way of the World may be applied that very dubious compliment paid by Mrs. Browning to Landor's Pentameron that, "were it not for the necessity of getting through a book, some of the pages are too delicious to turn over." The beginning of the third act, the description of Mirabell's feelings in the opening scene, and many other parts of The Way of the World, are not to be turned over, but to be re-read until the psychological subtlety of the sentiment, the perfume of the delicately chosen phrases, the music of the sentences, have produced their full effect upon the nerves. But, meanwhile, what of the action? The reader dies of a rose in aromatic pain, but the spectator fidgets in his stall, and wishes that the actors and actresses would be doing something. In no play of Congreve's is the literature so consummate, in none is the human interest in movement and surprise so utterly neglected, as in The Way of the World. The Old Bachelor, itself, is theatrical in comparison. We have slow, elaborate dialogue, spread out like some beautiful endless tapestry, and no action whatever. Nothing happens, nothing moves, positively from one end of The Way of the World to the other, and the only reward of the mere spectator is the occasional scene of wittily contrasted dialogue, Millamant pitted against Sir Wilful, Witwoud against Petulant, Lady Wishfort against her maid. With an experienced audience, prepared for an intellectual pleasure, the wit of these polished fragments would no doubt encourage a cultivation of patience through less lively portions of the play, but to spectators coming perfectly fresh to the piece, and expecting rattle and movement, this series of still-life pictures may easily be conceived to be exasperating, especially as the satire contained in them was extremely sharp and direct. Very slight record has been preserved of the manner in which The Way of the World was acted. The only part which seems to have been particularly distinguished was that of Mrs. Leigh in Lady Wishfort. Mrs. Bracegirdle, of course, was made for the part of Millamant, and her appearance in the second act, "with her fan spread and her streamers out, and a shoal of fools for tenders," was carefully prepared; yet we hear nothing of the effect produced. Mrs. Barry took the disagreeable character of Mrs. Marwood, and Betterton had no special chance for showing his qualities in Fainall. Witwoud and Petulant, who keep some of the scenes alive with their sallies, were Bower and Bowman, and Underhill played Sir Wilful. It is very tantalizing, and quite unaccountable, that no one seems to have preserved any tradition of the acting of this magnificent piece. In The Way of the World, as in The Old Bachelor, Congreve essayed a stratagem which Molire tried but once, in Le Misanthrope. It is one which is likely to please very much or greatly to annoy. It is the stimulation of curiosity all through the first act, without the introduction of one of the female characters who are described and, as it were, promised to the audience. It is probable that in the case of The Way of the World it was hardly a success. The analysis of character and delicate intellectual writing in the first act, devoid as it is of all stage-movement, may possibly have proved very tedious to auditors not subtle enough to enjoy Mirabell's account of the effect which Millamant's faults have upon him, or Witwoud's balanced depreciation of his friend Petulant. Even the mere reader discovers that the whole play brightens up after the entrance of Millamant, and probably that apparition is delayed too long. From this point, to the end of the second act, all scintillates and sparkles; and these are perhaps the most finished pages, for mere wit, in all existing comedy. The dialogue is a little metallic, but it is burnished to the highest perfection; and while one repartee rings against the other, the arena echoes as with shock after shock in a tilting-bout. In comparison with what we had had before Congreve's time that was best -- with The Man of Mode, for instance, and with The Country Wife -- the literary work in The Way of the World is altogether more polished, the wit more direct and effectual, the art of the comic poet more highely developed. There are fewer square inches of the canvas which the painter has roughly filled in, and neglected to finish; there is more that consciously demands critical admiration, less that can be, in Landor's phrase, pared away.

Why, then, did this marvellous comedy fail to please? Partly, no doubt, on account of its scholarly delicacy, too fine to hold the attention of the pit, and partly also, as we have seen, because of its too elaborate dialogue and absence of action. But there was more than this. Congreve was not merely a comedian, he was a satirist also -- asper jocum tentavit. He did not spare the susceptibilities of his fine ladies. His Cabal-Night at Lady Wishfort's is the direct original of Sheridan's School for Scandal; but in some ways the earlier picture is the more biting, the more disdainful. Without posing as a Timon or a Diogenes, and so becoming himself an object of curious interest, Congreve adopted the cynical tone, and threads the brightly-coloured crowd of social figures with a contemptuous smile upon his lips. When we come to speak of his plays as a whole, we shall revert to this trait, which is highly characteristic of his genius; it is here enough to point out that this peculiar air of careless superiority, which is decidedly annoying to audiences, reaches its climax in the last of Congreve's comedies. We have spoken with high praise of the end of the second act; but perhaps even this is surpassed in the third act by Lady Wishfort's unparalleled disorder at the sight of her complexion, "an arrant ash-colour, as I'm a person," and her voluble commands to her maid; or, in the fourth act, by the scene in which Millamant walks up and down the room reciting tags from the poets, not noticing Sir Wilful, the country clodpole squire, "ruder than Gothic," who takes the ejaculation, "Natural easy Suckling!" as a description of himself. It is to be noticed, as a proof that this play, in spite of its misfortunes, has made a deep impression on generations of hearers and readers, that it is fuller than any other of Congreve's plays of quotations that have become part of the language. It is from The Way of the World, for instance, that we take -- "To drink is a Christian diversion unknown to the Turk and the Persian"; while it would be interesting to know whether it is by a pure coincidence that Tennyson, in perhaps the most famous of all his phrases, comes so near to Congreve's "'Tis better to have been left, than never to have been loved." Paradise Lost Miltons speaker begins Paradise Lost by stating that his subject will be Adam and Eves disobedience and fall from grace. He invokes a heavenly muse and asks for help in relating his ambitious story and Gods plan for humankind. The action begins with Satan and his fellow rebel angels who are found chained to a lake of fire in Hell. They quickly free themselves and fly to land, where they discover minerals and construct Pandemonium, which will be their meeting place. Inside Pandemonium, the rebel angels, who are now devils, debate whether they should begin another war with God. Beezelbub suggests that they attempt to corrupt Gods beloved new creation, humankind. Satan agrees, and volunteers to go himself. As he prepares to leave Hell, he is met at the gates by his children, Sin and Death, who follow him and build a bridge between Hell and Earth. In Heaven, God orders the angels together for a council of their own. He tells them of Satans intentions, and the Son volunteers himself to make the sacrifice for humankind. Meanwhile, Satan travels through Night and Chaos and finds Earth. He disguises himself as a cherub to get past the Archangel Uriel, who stands guard at the sun. He tells Uriel that he wishes to see and praise Gods glorious creation, and Uriel assents. Satan then lands on Earth and takes a moment to reflect. Seeing the splendor of Paradise brings him pain rather than pleasure. He reaffirms his decision to make evil his good, and continue to commit crimes against God. Satan leaps over Paradises wall, takes the form of a cormorant (a large bird), and perches himself atop the Tree of Life. Looking down at Satan from his post, Uriel notices the volatile emotions reflected in the face of this so-called cherub and warns the other angels that an impostor is in their midst. The other angels agree to search the Garden for intruders. Meanwhile, Adam and Eve tend the Garden, carefully obeying Gods supreme order not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. After a long day of work, they return to their bower and rest. There, Satan takes the form of a toad and whispers into Eves ear. Gabriel, the angel set to guard Paradise, finds Satan there and orders him to leave. Satan prepares to battle Gabriel, but God makes a sign appear in the skythe golden scales of justiceand Satan scurries away. Eve awakes and tells Adam about a dream she had, in which an angel tempted her to eat from the forbidden tree. Worried about his creation, God sends Raphael down to Earth to teach Adam and Eve of the dangers they face with Satan. Raphael arrives on Earth and eats a meal with Adam and Eve. Raphael relates the story of Satans envy over the Sons appointment as Gods second-in-command. Satan gathered other angels together who were also angry to hear this news, and together they plotted a war against God. Abdiel decides not to join Satans army and returns to God. The angels then begin to fight, with Michael and Gabriel serving as coleaders for Heavens army. The battle lasts two days, when God sends the Son to end the war and deliver Satan and his rebel angels to Hell. Raphael tells Adam about Satans evil motives to corrupt them, and warns Adam to watch out for Satan. Adam asks Raphael to tell him the story of creation. Raphael tells Adam that God sent the Son into Chaos to create the universe. He created the earth and stars and other planets. Curious, Adam asks Raphael about the movement of the stars and planets. Eve retires, allowing Raphael and Adam to speak alone. Raphael promptly warns Adam about his seemingly unquenchable search for knowledge. Raphael tells Adam that he will learn all he needs to know, and that any other knowledge is not meant for humans to comprehend. Adam tells Raphael about his first memories, of waking up and wondering who he was, what he was, and where he was. Adam says that God spoke to him and told him many things, including his order not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. After the story, Adam confesses to Raphael his intense physical attraction to Eve. Raphael reminds Adam that he must love Eve more purely and spiritually. With this final bit of advice, Raphael leaves Earth and returns to Heaven. Eight days after his banishment, Satan returns to Paradise. After closely studying the animals of Paradise, he chooses to take the form of the serpent. Meanwhile, Eve suggests to Adam that they work separately for awhile, so they can get more work done. Adam is hesitant but then assents. Satan searches for Eve and is delighted to find her alone. In the form of a serpent, he talks to Eve and compliments her on her beauty and godliness. She is amazed to find an animal that can speak. She asks how he learned to speak, and he tells her that it was by eating from the Tree of Knowledge. He tells Eve that God actually wants her and Adam to eat from the tree, and that his order is merely a test of their courage. She is hesitant at first but then reaches for a fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and eats. She becomes distraught and searches for Adam. Adam has been busy making a wreath of flowers for Eve. When Eve finds Adam, he drops the wreath and is horrified to find that Eve has eaten from the forbidden tree. Knowing that she has fallen, he decides that he would rather be fallen with her than remain pure and lose her. So he eats from the fruit as well. Adam looks at Eve in a new way, and together they turn to lust. God immediately knows of their disobedience. He tells the angels in Heaven that Adam and Eve must be punished, but with a display of both justice and mercy. He sends the Son to give out the punishments. The Son first punishes the serpent whose body Satan took, and condemns it never to walk upright again. Then the Son tells Adam and Eve that they must now suffer pain and death. Eve and all women must suffer the pain of childbirth and must submit to their husbands, and Adam and all men must hunt and grow their own food on a depleted Earth. Meanwhile, Satan returns to Hell where he is greeted with cheers. He speaks to the devils in Pandemonium, and everyone believes that he has beaten God. Sin and Death travel the bridge they built on their way to Earth. Shortly thereafter, the devils unwillingly transform into snakes and try to reach fruit from imaginary trees that shrivel and turn to dust as they reach them.

God tells the angels to transform the Earth. After the fall, humankind must suffer hot and cold seasons instead of the consistent temperatures before the fall. On Earth, Adam and Eve fear their approaching doom. They blame each other for their disobedience and become increasingly angry at one another. In a fit of rage, Adam wonders why God ever created Eve. Eve begs Adam not to abandon her. She tells him that they can survive by loving each other. She accepts the blame because she has disobeyed both God and Adam. She ponders suicide. Adam, moved by her speech, forbids her from taking her own life. He remembers their punishment and believes that they can enact revenge on Satan by remaining obedient to God. Together they pray to God and repent. God hears their prayers, and sends Michael down to Earth. Michael arrives on Earth, and tells them that they must leave Paradise. But before they leave, Michael puts Eve to sleep and takes Adam up onto the highest hill, where he shows him a vision of humankinds future. Adam sees the sins of his children, and his childrens children, and his first vision of death. Horrified, he asks Michael if there is any alternative to death. Generations to follow continue to sin by lust, greed, envy, and pride. They kill each other selfishly and live only for pleasure. Then Michael shows him the vision of Enoch, who is saved by God as his warring peers attempt to kill him. Adam also sees the story of Noah and his family, whose virtue allows them to be chosen to survive the flood that kills all other humans. Adam feels remorse for death and happiness for humankinds redemption. Next is the vision of Nimrod and the Tower of Babel. This story explains the perversion of pure language into the many languages that are spoken on Earth today. Adam sees the triumph of Moses and the Israelites, and then glimpses the Sons sacrifice to save humankind. After this vision, it is time for Adam and Eve to leave Paradise. Eve awakes and tells Adam that she had a very interesting and educating dream. Led by Michael, Adam and Eve slowly and woefully leave Paradise hand in hand into a new world. Robinson Crusoe Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the town of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. Encouraged by his father to study law, Crusoe expresses his wish to go to sea instead. His family is against Crusoe going out to sea, and his father explains that it is better to seek a modest, secure life for oneself. Initially, Robinson is committed to obeying his father, but he eventually succumbs to temptation and embarks on a ship bound for London with a friend. When a storm causes the near deaths of Crusoe and his friend, the friend is dissuaded from sea travel, but Crusoe still goes on to set himself up as merchant on a ship leaving London. This trip is financially successful, and Crusoe plans another, leaving his early profits in the care of a friendly widow. The second voyage does not prove as fortunate: the ship is seized by Moorish pirates, and Crusoe is enslaved to a potentate in the North African town of Sallee. While on a fishing expedition, he and a slave boy break free and sail down the African coast. A kindly Portuguese captain picks them up, buys the slave boy from Crusoe, and takes Crusoe to Brazil. In Brazil, Crusoe establishes himself as a plantation owner and soon becomes successful. Eager for slave labor and its economic advantages, he embarks on a slave-gathering expedition to West Africa but ends up shipwrecked off of the coast of Trinidad. Crusoe soon learns he is the sole survivor of the expedition and seeks shelter and food for himself. He returns to the wrecks remains twelve times to salvage guns, powder, food, and other items. Onshore, he finds goats he can graze for meat and builds himself a shelter. He erects a cross that he inscribes with the date of his arrival, September 1, 1659, and makes a notch every day in order never to lose track of time. He also keeps a journal of his household activities, noting his attempts to make candles, his lucky discovery of sprouting grain, and his construction of a cellar, among other events. In June 1660, he falls ill and hallucinates that an angel visits, warning him to repent. Drinking tobacco-steeped rum, Crusoe experiences a religious illumination and realizes that God has delivered him from his earlier sins. After recovering, Crusoe makes a survey of the area and discovers he is on an island. He finds a pleasant valley abounding in grapes, where he builds a shady retreat. Crusoe begins to feel more optimistic about being on the island, describing himself as its king. He trains a pet parrot, takes a goat as a pet, and develops skills in basket weaving, bread making, and pottery. He cuts down an enormous cedar tree and builds a huge canoe from its trunk, but he discovers that he cannot move it to the sea. After building a smaller boat, he rows around the island but nearly perishes when swept away by a powerful current. Reaching shore, he hears his parrot calling his name and is thankful for being saved once again. He spends several years in peace. One day Crusoe is shocked to discover a mans footprint on the beach. He first assumes the footprint is the devils, then decides it must belong to one of the cannibals said to live in the region. Terrified, he arms himself and remains on the lookout for cannibals. He also builds an underground cellar in which to herd his goats at night and devises a way to cook underground. One evening he hears gunshots, and the next day he is able to see a ship wrecked on his coast. It is empty when he arrives on the scene to investigate. Crusoe once again thanks Providence for having been saved. Soon afterward, Crusoe discovers that the shore has been strewn with human carnage, apparently the remains of a cannibal feast. He is alarmed and continues to be vigilant. Later Crusoe catches sight of thirty cannibals heading for shore with their victims. One of the victims is killed. Another one, waiting to be slaughtered, suddenly breaks free and runs toward Crusoes dwelling. Crusoe protects him, killing one of the pursuers and injuring the other, whom the victim finally kills. Well-armed, Crusoe defeats most of the cannibals onshore. The victim vows total submission to Crusoe in gratitude for his liberation. Crusoe names him Friday, to commemorate the day on which his life was saved, and takes him as his servant. Finding Friday cheerful and intelligent, Crusoe teaches him some English words and some elementary Christian concepts. Friday, in turn, explains that the cannibals are divided into distinct nations and that they only eat their enemies. Friday also informs Crusoe that the cannibals saved the men from the shipwreck Crusoe witnessed earlier, and that those men, Spaniards, are living nearby. Friday expresses a longing to return to his people, and Crusoe is upset at the prospect of losing Friday. Crusoe then entertains the idea of making contact with the Spaniards, and Friday admits that he would rather die than lose Crusoe. The two build a boat to visit the cannibals land together. Before they have a chance to leave, they are surprised by the arrival of twenty-one cannibals in canoes. The cannibals are holding three victims, one of whom is in European dress. Friday and Crusoe kill most of the cannibals and release the European, a Spaniard. Friday is overjoyed to discover that another of the rescued victims is his father. The four men return to Crusoes dwelling for food and rest. Crusoe prepares to welcome them into his community permanently. He sends Fridays father and the Spaniard out in a canoe to explore the nearby land. Eight days later, the sight of an approaching English ship alarms Friday. Crusoe is suspicious. Friday and Crusoe watch as eleven men take three captives onshore in a boat. Nine of the men explore the land, leaving two to guard the captives. Friday and Crusoe overpower these men and release the captives, one of whom is the captain of the ship, which has been taken in a mutiny. Shouting to the remaining mutineers from different points, Friday and Crusoe confuse and tire the men by making them run from place to place. Eventually they confront the mutineers, telling them that all may escape with their lives except the ringleader. The men surrender. Crusoe and the captain pretend that the island is an imperial territory and that the governor has spared their lives in order to send them all to England to face justice. Keeping five men as hostages, Crusoe sends the other men out to seize the ship. When the ship is brought in, Crusoe nearly faints.

On December 19, 1686, Crusoe boards the ship to return to England. There, he finds his family is deceased except for two sisters. His widow friend has kept Crusoes money safe, and after traveling to Lisbon, Crusoe learns from the Portuguese captain that his plantations in Brazil have been highly profitable. He arranges to sell his Brazilian lands. Wary of sea travel, Crusoe attempts to return to England by land but is threatened by bad weather and wild animals in northern Spain. Finally arriving back in England, Crusoe receives word that the sale of his plantations has been completed and that he has made a considerable fortune. After donating a portion to the widow and his sisters, Crusoe is restless and considers returning to Brazil, but he is dissuaded by the thought that he would have to become Catholic. He marries, and his wife dies. Crusoe finally departs for the East Indies as a trader in 1694. He revisits his island, finding that the Spaniards are governing it well and that it has become a prosperous colony. William Blake Blakes Songs of Innocence and Experience (1794) juxtapose the innocent, pastoral world of childhood against an adult world of corruption and repression; while such poems as The Lamb represent a meek virtue, poems like The Tyger exhibit opposing, darker forces. Thus the collection as a whole explores the value and limitations of two different perspectives on the world. Many of the poems fall into pairs, so that the same situation or problem is seen through the lens of innocence first and then experience. Blake does not identify himself wholly with either view; most of the poems are dramaticthat is, in the voice of a speaker other than the poet himself. Blake stands outside innocence and experience, in a distanced position from which he hopes to be able to recognize and correct the fallacies of both. In particular, he pits himself against despotic authority, restrictive morality, sexual repression, and institutionalized religion; his great insight is into the way these separate modes of control work together to squelch what is most holy in human beings. The Songs of Innocence dramatize the naive hopes and fears that inform the lives of children and trace their transformation as the child grows into adulthood. Some of the poems are written from the perspective of children, while others are about children as seen from an adult perspective. Many of the poems draw attention to the positive aspects of natural human understanding prior to the corruption and distortion of experience. Others take a more critical stance toward innocent purity: for example, while Blake draws touching portraits of the emotional power of rudimentary Christian values, he also exposesover the heads, as it were, of the innocentChristianitys capacity for promoting injustice and cruelty. The Songs of Experience work via parallels and contrasts to lament the ways in which the harsh experiences of adult life destroy what is good in innocence, while also articulating the weaknesses of the innocent perspective (The Tyger, for example, attempts to account for real, negative forces in the universe, which innocence fails to confront). These latter poems treat sexual morality in terms of the repressive effects of jealousy, shame, and secrecy, all of which corrupt the ingenuousness of innocent love. With regard to religion, they are less concerned with the character of individual faith than with the institution of the Church, its role in politics, and its effects on society and the individual mind. Experience thus adds a layer to innocence that darkens its hopeful vision while compensating for some of its blindness. The style of the Songs of Innocence and Experience is simple and direct, but the language and the rhythms are painstakingly crafted, and the ideas they explore are often deceptively complex. Many of the poems are narrative in style; others, like The Sick Rose and The Divine Image, make their arguments through symbolism or by means of abstract concepts. Some of Blakes favorite rhetorical techniques are personification and the reworking of Biblical symbolism and language. Blake frequently employs the familiar meters of ballads, nursery rhymes, and hymns, applying them to his own, often unorthodox conceptions. This combination of the traditional with the unfamiliar is consonant with Blakes perpetual interest in reconsidering and reframing the assumptions of human thought and social behavior. Jude the Obscure Jude Fawley dreams of studying at the university in Christminster, but his background as an orphan raised by his working-class aunt leads him instead into a career as a stonemason. He is inspired by the ambitions of the town schoolmaster, Richard Phillotson, who left for Christminster when Jude was a child. However, Jude falls in love with a young woman named Arabella, is tricked into marrying her, and cannot leave his home village. When their marriage goes sour and Arabella moves to Australia, Jude resolves to go to Christminster at last. However, he finds that his attempts to enroll at the university are met with little enthusiasm.

Jude meets his cousin Sue Bridehead and tries not to fall in love with her. He arranges for her to work with Phillotson in order to keep her in Christminster, but is disappointed when he discovers that the two are engaged to be married. Once they marry, Jude is not surprised to find that Sue is not happy with her situation. She can no longer tolerate the relationship and leaves her husband to live with Jude. Both Jude and Sue get divorced, but Sue does not want to remarry. Arabella reveals to Jude that they have a son in Australia, and Jude asks to take him in. Sue and Jude serve as parents to the little boy and have two children of their own. Jude falls ill, and when he recovers, he decides to return to Christminster with his family. They have trouble finding lodging because they are not married, and Jude stays in an inn separate from Sue and the children. At night Sue takes Jude's son out to look for a room, and the little boy decides that they would be better off without so many children. In the morning, Sue goes to Jude's room and eats breakfast with him. They return to the lodging house to find that Jude's son has hanged the other two children and himself. Feeling she has been punished by God for her relationship with Jude, Sue goes back to live with Phillotson, and Jude is tricked into living with Arabella again. Jude dies soon after. Jude the Obscure focuses on the life of a country stonemason, Jude, and his love for his cousin Sue, a schoolteacher. From the beginning Jude knows that marriage is an ill-fated venture in his family, and he believes that his love for Sue curses him doubly, because they are both members of a cursed clan. While love could be identified as a central theme in the novel, it is the institution of marriage that is the work's central focus. Jude and Sue are unhappily married to other people, and then drawn by an inevitable bond that pulls them together. Their relationship is beset by tragedy, not only because of the family curse but also by society's reluctance to accept their marriage as legitimate.

The horrifying murder-suicide of Jude's children is no doubt the climax of the book's action, and the other events of the novel rise in a crescendo to meet that one act. From there, Jude and Sue feel they have no recourse but to return to their previous, unhappy marriages and die within the confinement created by their youthful errors. They are drawn into an endless cycle of self-erected oppression and cannot break free. In a society unwilling to accept their rejection of convention, they are ostracized. Jude's son senses wrongdoing in his own conception and acts in a way that he thinks will help his parents and his siblings. The children are the victims of society's unwillingness to accept Jude and Sue as man and wife, and Sue's own feelings of shame from her divorce.

Jude's initial failure to attend the university becomes less important as the novel progresses, but his obsession with Christminster remains. Christminster is the site of Jude's first encounters with Sue, the tragedy that dominates the book, and Jude's final moments and death. It acts upon Jude, Sue, and their family as a representation of the unattainable and dangerous things to which Jude aspires.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Pre-Islamic Period (Jahilliya)Document2 pagesPre-Islamic Period (Jahilliya)Kurtis ChomiNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- NEET - Halo Alkanes and Halo Arenes Practice PaperDocument3 pagesNEET - Halo Alkanes and Halo Arenes Practice PaperGanga DharaNo ratings yet

- Food Safety LicenseDocument2 pagesFood Safety LicenseGanga DharaNo ratings yet

- Resume: Mohsin KhanDocument2 pagesResume: Mohsin KhanGanga DharaNo ratings yet

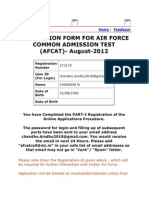

- Air ForceDocument2 pagesAir ForceGanga DharaNo ratings yet

- Gold Analysis India PDFDocument35 pagesGold Analysis India PDFGanga Dhara100% (1)

- Application Letter 17741Document1 pageApplication Letter 17741Ganga DharaNo ratings yet

- Shimoga .AshokDocument4 pagesShimoga .AshokGanga DharaNo ratings yet

- Glasswares 1Document1 pageGlasswares 1Ganga DharaNo ratings yet

- SBI ChallanDocument1 pageSBI ChallanGanga DharaNo ratings yet

- ReshmaDocument2 pagesReshmaGanga DharaNo ratings yet

- Kompetensi Guru Prespektif Al GhazaliDocument14 pagesKompetensi Guru Prespektif Al Ghazaliنور هدايةNo ratings yet

- Wittgenstein Faith and ReasonDocument15 pagesWittgenstein Faith and ReasonCally docNo ratings yet

- #1333 - Rest in The LordDocument8 pages#1333 - Rest in The Lorditisme_angelaNo ratings yet

- History of Literary CriticismDocument71 pagesHistory of Literary CriticismJhenjhen Ganda100% (1)

- Baden Vienna PDFDocument17 pagesBaden Vienna PDFlucii_89No ratings yet

- فرشي التراب يضمني وهو غطائيDocument4 pagesفرشي التراب يضمني وهو غطائيmozidaNo ratings yet

- Camp Meeting Program 2022Document20 pagesCamp Meeting Program 2022Allen M MubitaNo ratings yet

- Newsletter Week 10Document8 pagesNewsletter Week 10api-246371804No ratings yet

- Principles Fundamental of The Church-State ControversyDocument9 pagesPrinciples Fundamental of The Church-State ControversyRahul BhadwaNo ratings yet

- A Historical Background of Life and Social Reforms of Sree Narayana GuruDocument56 pagesA Historical Background of Life and Social Reforms of Sree Narayana GuruManeesh VNo ratings yet

- Janux Transcript 10cDocument2 pagesJanux Transcript 10cWright SomesNo ratings yet

- Article Toward A Pentecostal Theology of GraceDocument35 pagesArticle Toward A Pentecostal Theology of GraceJohn NierrasNo ratings yet

- AnanikDocument168 pagesAnanikTenaLeko100% (1)

- Nock, A. D. (1962) - Sapor I and The Apollo of Bryaxis. American Journal of Archaeology, 66 (3), 307-310Document5 pagesNock, A. D. (1962) - Sapor I and The Apollo of Bryaxis. American Journal of Archaeology, 66 (3), 307-310Dimi RatatouilleNo ratings yet

- MandatumDocument3 pagesMandatumEly Kuan100% (1)

- The Blood of Jesus - Ernest Angley (1995)Document17 pagesThe Blood of Jesus - Ernest Angley (1995)http://MoreOfJesus.RR.NU100% (1)

- Degeneration of Muslims in SubcontinentDocument2 pagesDegeneration of Muslims in Subcontinentsohail abdulqadirNo ratings yet

- Cessation of A Project And: Belle Corp Vs MacasusiDocument9 pagesCessation of A Project And: Belle Corp Vs MacasusikathNo ratings yet

- How Vedic Yagnyas Can Cause RainfallDocument2 pagesHow Vedic Yagnyas Can Cause Rainfallvijaychemuturi0% (1)

- Samuel J Rangel: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesSamuel J Rangel: Objectiveapi-320117481No ratings yet

- Sobre Narayana MaharajaDocument4 pagesSobre Narayana MaharajaDhanur Dhara DasaNo ratings yet

- 2520 June Official Version PDFDocument130 pages2520 June Official Version PDFHans SchauerNo ratings yet

- Taj Mahal - Foundation EnglishDocument11 pagesTaj Mahal - Foundation EnglishSyed Osama Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Bylaws of Church of God, Colorado Conference: Approved by Governance BoardDocument10 pagesBylaws of Church of God, Colorado Conference: Approved by Governance BoardCoconfcog100% (1)

- Marxist CriticismDocument20 pagesMarxist CriticismBhakti Bagoes Ibrahim100% (1)

- ELIT 117 - Survey of Philippine Literature in EnglishDocument21 pagesELIT 117 - Survey of Philippine Literature in EnglishWinter BacalsoNo ratings yet

- The Radiant Buddhist NunDocument3 pagesThe Radiant Buddhist NunFrank FeldmanNo ratings yet

- A Search For Eternal HappinessDocument24 pagesA Search For Eternal Happinesshappiest1No ratings yet