Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SC of Urban Solid Waste Management

SC of Urban Solid Waste Management

Uploaded by

Andre SuitoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Fundamentals of Urban and Regional PlanningDocument33 pagesFundamentals of Urban and Regional PlanningMaru Pablo75% (4)

- Waste to Energy in the Age of the Circular Economy: Best Practice HandbookFrom EverandWaste to Energy in the Age of the Circular Economy: Best Practice HandbookNo ratings yet

- Hyderabad - City Development Plan Chapter PDFDocument9 pagesHyderabad - City Development Plan Chapter PDFShivangi AroraNo ratings yet

- Week 4Document70 pagesWeek 4Manvi YadavNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management AssignmentDocument16 pagesSolid Waste Management AssignmentAlfatah muhumed100% (1)

- Municipal Solid Waste Management Challenges in Developing Countries - Kenyan Case StudyDocument9 pagesMunicipal Solid Waste Management Challenges in Developing Countries - Kenyan Case StudyMoe GyiNo ratings yet

- Zurbruegg 1998 LandfillDocument9 pagesZurbruegg 1998 LandfillNivea ZuniegaNo ratings yet

- What A Waste - A Global Review of Solid Waste ManagementDocument116 pagesWhat A Waste - A Global Review of Solid Waste ManagementrenodfbNo ratings yet

- New Rural Development Paradigm PresentationDocument28 pagesNew Rural Development Paradigm PresentationHeinzNo ratings yet

- Waste To Wealth by DR Sivapalan KathiravaleDocument26 pagesWaste To Wealth by DR Sivapalan Kathiravalekaitzer100% (1)

- Solid-Wastefinaldraft-12 29 15 PDFDocument62 pagesSolid-Wastefinaldraft-12 29 15 PDFDiana DainaNo ratings yet

- Solid Wastefinaldraft 12.29.15Document62 pagesSolid Wastefinaldraft 12.29.15Justine LagonoyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Climate Change On Urban Settlements in ColombiaDocument98 pagesImpact of Climate Change On Urban Settlements in ColombiaUrbanway100% (1)

- 3 Solid Waste 1.8Document55 pages3 Solid Waste 1.8Zinc MarquezNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management in Asian Countries: Problems and IssuesDocument11 pagesSolid Waste Management in Asian Countries: Problems and IssuesL M ArisonNo ratings yet

- AGC206Document10 pagesAGC206wong NXNo ratings yet

- Resettlement in China: Policy, Practice and Experiences: SHI Guoqing, ProfessorDocument81 pagesResettlement in China: Policy, Practice and Experiences: SHI Guoqing, Professorbhoj raj singalNo ratings yet

- 12 - Bongertmann T, Schoebiz L. Country Case TanzaniaDocument33 pages12 - Bongertmann T, Schoebiz L. Country Case TanzaniaaksalirkaNo ratings yet

- The Political Economy of Environmental Policy in Indonesia - PresentationDocument20 pagesThe Political Economy of Environmental Policy in Indonesia - PresentationADB Poverty ReductionNo ratings yet

- 3 Chapter 2 Literature Review PDFDocument53 pages3 Chapter 2 Literature Review PDFJohnlorenz Icaro de ChavezNo ratings yet

- Turner, Kerry - LITTORAL 2010 - The Role of The Coast in The Economy of NationsDocument19 pagesTurner, Kerry - LITTORAL 2010 - The Role of The Coast in The Economy of NationsjonlistyNo ratings yet

- AAG Philippine Solid Wastes Nov2017Document4 pagesAAG Philippine Solid Wastes Nov2017Gherald EdañoNo ratings yet

- SE07 - Solid Waste Management - SAPUAYDocument19 pagesSE07 - Solid Waste Management - SAPUAYKarl Lorenzo BabianoNo ratings yet

- Project/Programme ProposalDocument95 pagesProject/Programme ProposalPascal TebzaNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Management of Transboundary Waters in EuropeDocument37 pagesSustainable Management of Transboundary Waters in EuropeSafi HusseinNo ratings yet

- 354 1037 1 SMDocument8 pages354 1037 1 SMReynaldo LlameraNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management in Egypt: Section 2Document9 pagesSolid Waste Management in Egypt: Section 2Waled HantashNo ratings yet

- Lect-1 URBANISATION & TRANSPORTATION - SCENARIO, ISSUES AND STRETEGIESDocument28 pagesLect-1 URBANISATION & TRANSPORTATION - SCENARIO, ISSUES AND STRETEGIESDarshan DaveNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document2 pagesChapter 1Joshua SalazarNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 4 Waste Management Part I - Intro (New)Document23 pagesCHAPTER 4 Waste Management Part I - Intro (New)ainsahNo ratings yet

- Unit 2: The Global Situation: STAT101: Statistics in The Modern WorldDocument14 pagesUnit 2: The Global Situation: STAT101: Statistics in The Modern WorldAmna MazharNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXtoDocument11 pagesFULLTEXtoDEBANG EDCES R.No ratings yet

- Poverty and The Environment in Rural Cambodia: Tong Kimsun and Sry BopharathDocument13 pagesPoverty and The Environment in Rural Cambodia: Tong Kimsun and Sry BopharathMartha Jelle Deliquiña BlancoNo ratings yet

- Water Supply in EthiopiaDocument7 pagesWater Supply in EthiopiaKalu AbuNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id288963Document10 pagesSSRN Id288963A channelNo ratings yet

- Urbanization and Sustainability Challeng PDFDocument10 pagesUrbanization and Sustainability Challeng PDFFakhrul IslamNo ratings yet

- The Role of Waste To Energy (WTE) in A Circular Economy SocietyDocument35 pagesThe Role of Waste To Energy (WTE) in A Circular Economy SocietyJorge MartinezNo ratings yet

- Towards Zero Waste in Emerging Countries - A South African ExperienceDocument13 pagesTowards Zero Waste in Emerging Countries - A South African Experienceata radityaNo ratings yet

- Resources, Conservation and Recycling: Socio-Economic Profile and Profitability of Faecal Sludge Emptying CompaniesDocument8 pagesResources, Conservation and Recycling: Socio-Economic Profile and Profitability of Faecal Sludge Emptying CompaniesEddiemtongaNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste MGT IndiaDocument21 pagesSolid Waste MGT IndiaGopika GhNo ratings yet

- Presentation ResearchDocument8 pagesPresentation Researchapi-3698040No ratings yet

- How Inclusive Is The Growth in Asia and What Can Governments Do To Make Growth More Inclusive? (Presentation)Document9 pagesHow Inclusive Is The Growth in Asia and What Can Governments Do To Make Growth More Inclusive? (Presentation)ADB Poverty ReductionNo ratings yet

- Dryland Poverty: Characteristics, Policy Responses, New Challenges and Opportunities - PresentationDocument16 pagesDryland Poverty: Characteristics, Policy Responses, New Challenges and Opportunities - PresentationADB Poverty ReductionNo ratings yet

- Buku 2 PDFDocument17 pagesBuku 2 PDFSyafiq ShafieiNo ratings yet

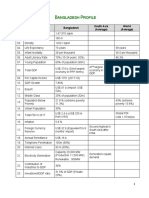

- Angladesh Rofile: Sl. No. Items Bangladesh South Asia (Average) World (Average)Document2 pagesAngladesh Rofile: Sl. No. Items Bangladesh South Asia (Average) World (Average)raihan2235No ratings yet

- Republic of ChinaDocument18 pagesRepublic of Chinaapi-3696178No ratings yet

- NSWMC (2015)Document60 pagesNSWMC (2015)Hazel Ivy JeremiasNo ratings yet

- Plan WorkDocument5 pagesPlan Workbright osakweNo ratings yet

- Overview of DisastersDocument26 pagesOverview of DisastersYamang TagguNo ratings yet

- Real Estate in The PhilippinesDocument40 pagesReal Estate in The PhilippinesPurchiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter2 8 UrbanDocument30 pagesChapter2 8 Urbanlmary20074193No ratings yet

- Profile New ZealandDocument2 pagesProfile New Zealandjalhareem511No ratings yet

- 08 - Solid Waste Management - Part 1Document40 pages08 - Solid Waste Management - Part 12021301152No ratings yet

- Clean It Right - Dumpsite Management in IndiaDocument32 pagesClean It Right - Dumpsite Management in Indiasaravanan gNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - Municipal Waste Management PDFDocument17 pagesChapter 8 - Municipal Waste Management PDFlithaNo ratings yet

- Sustainable DevelopmentDocument33 pagesSustainable DevelopmentMadhukar JayantNo ratings yet

- Impact of Urbanization and Industrialization and Role of EIA On Sustainable DevelopmentDocument148 pagesImpact of Urbanization and Industrialization and Role of EIA On Sustainable DevelopmentAradhana Kanchan SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Municipal Solid Waste Management in Africa: Strategies and Livelihoods in Yaoundé, Cameroon - Waste ManagementDocument12 pagesMunicipal Solid Waste Management in Africa: Strategies and Livelihoods in Yaoundé, Cameroon - Waste ManagementNKWENTI DESHNICNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Moisture Content of Yola Municipal Solid WasteDocument13 pagesEvaluation of Moisture Content of Yola Municipal Solid WasteAbu MaryamNo ratings yet

- Governance, Environment, and Sustainable Human Development in Drc: The State, Civil Society and the Private Economy and Environmental Policies in Changing Trends in the Human Development Index After IndependenceFrom EverandGovernance, Environment, and Sustainable Human Development in Drc: The State, Civil Society and the Private Economy and Environmental Policies in Changing Trends in the Human Development Index After IndependenceNo ratings yet

- IncineratorDocument20 pagesIncineratorAndre Suito100% (2)

- Indo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignDocument6 pagesIndo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Landfills: The Future of Land Disposal of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW)Document29 pagesSustainable Landfills: The Future of Land Disposal of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW)Andre Suito100% (1)

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management Workshop Detail Design ImplementationDocument16 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management Workshop Detail Design ImplementationAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management MethodsDocument44 pagesSolid Waste Management MethodsAndre Suito78% (9)

- Solid, Toxic and Hazardous Waste: Cunningham - Cunningham - Saigo: Environmental Science 7Document42 pagesSolid, Toxic and Hazardous Waste: Cunningham - Cunningham - Saigo: Environmental Science 7Andre Suito100% (7)

- To The Methodology of The Investigation For A Sanitary Landfill SiteDocument27 pagesTo The Methodology of The Investigation For A Sanitary Landfill SiteAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management WorkshopDocument17 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management WorkshopAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Indo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignDocument6 pagesIndo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopDocument27 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopAndre Suito100% (1)

- Evolution of Landfill Technology: South American ContextDocument57 pagesEvolution of Landfill Technology: South American ContextAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste MGT Technologies A FordeDocument23 pagesSolid Waste MGT Technologies A FordeAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Waste ManagementDocument29 pagesWaste ManagementAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopDocument32 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Waste Management in IndiaDocument26 pagesWaste Management in IndiaAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Hazardous WasteDocument22 pagesHazardous WasteAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Desentralization Waste MNGMT in VietnamDocument27 pagesDesentralization Waste MNGMT in VietnamAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Zrotary Clean & GreenDocument15 pagesZrotary Clean & GreenAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Unfcc-Green House TrainingDocument122 pagesUnfcc-Green House TrainingAndre Suito100% (1)

- Indonesia CDM ProjectDocument19 pagesIndonesia CDM ProjectAnh DNNo ratings yet

- Manual of Sanitary Landfill Permits and AprovalDocument142 pagesManual of Sanitary Landfill Permits and AprovalAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Urbanisation and Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Case Study of MumbaiDocument15 pagesUrbanisation and Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Case Study of MumbaiAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Ina - Emisi Gas Di IndonesiaDocument14 pagesIna - Emisi Gas Di IndonesiaAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management in Indian Ocean Islands & SeychellesDocument15 pagesSolid Waste Management in Indian Ocean Islands & SeychellesAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Landfills: Remediation of Former Dumpsites AND Design of Engineered LandfillsDocument19 pagesLandfills: Remediation of Former Dumpsites AND Design of Engineered LandfillsAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- SC of Recycle PaperDocument160 pagesSC of Recycle PaperAndre Suito100% (1)

- Report of Kalimantan Urban Dev ProjectDocument91 pagesReport of Kalimantan Urban Dev ProjectAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- 3R Implementation in Indonesia Asia 3R ConferenceDocument20 pages3R Implementation in Indonesia Asia 3R ConferenceAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- SC of Conrad - Britannia - LandfillDocument33 pagesSC of Conrad - Britannia - LandfillAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Book of Asesment Info About WasteDocument63 pagesBook of Asesment Info About WasteAndre Suito100% (1)

SC of Urban Solid Waste Management

SC of Urban Solid Waste Management

Uploaded by

Andre SuitoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SC of Urban Solid Waste Management

SC of Urban Solid Waste Management

Uploaded by

Andre SuitoCopyright:

Available Formats

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Urban Solid Waste Management in Low-Income Countries of Asia

How to Cope with the Garbage Crisis

Christian Zurbrügg

Department of Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries (SANDEC)

Swiss Federal Institute for Environmental Science and Technology (EAWAG)

P.O. Box 611

8600 – Duebendorf

Switzerland

Phone: +41-1-823 5423

Fax: +41-1-823 5399

email: zurbrugg@eawag.ch

1. Introduction

Human activities create waste, and it is the way these wastes are handled, stored, collected

and disposed of, which can pose risks to the environment and to public health. Where intense

human activities concentrate, such as in urban centres, appropriate and safe solid waste

management (SWM) are of utmost importance to allow healthy living conditions for the

population. This fact has been acknowledged by most governments, however many

municipalities are struggling to provide even the most basic services. Typically one to two

thirds of the solid waste generated is not collected (World Resources Institute, et al., 1996).

As a result, the uncollected waste, which is often also mixed with human and animal excreta,

is dumped indiscriminately in the streets and in drains, so contributing to flooding, breeding

of insect and rodent vectors and the spread of diseases (UNEP-IETC, 1996). Most of the

municipal solid waste in low-income Asian countries which is collected is dumped on land in

a more or less uncontrolled manner. Such inadequate waste disposal creates serious

environmental problems that affect health of humans and animals and cause serious economic

and other welfare losses. The environmental degradation caused by inadequate disposal of

waste can be expressed by the contamination of surface and ground water through leachate,

soil contamination through direct waste contact or leachate, air pollution by burning of wastes,

spreading of diseases by different vectors like birds, insects and rodents, or uncontrolled

release of methan by anaerobic decomposition of waste

Throughout the cities it is the urban poor that suffer most from the life-threatening conditions

deriving from deficient SWM (Kungskulniti, 1990; Lohani, 1984), as municipal authorities

tend to allocate their limited financial resources to the richer areas of higher tax yields where

citizens with more political power reside. Usually, wealthy residents use part of their income

to avoid direct exposure to the environmental problems close to home, and the problems are

shifted away from their neighbourhood to elsewhere. Thus, although environmental problems

at the household or neighbourhood level may recede in higher income areas, citywide and

regional environmental degradation, due to a deficient SWM, remains or increases.

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 1

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Urbanization and Urban Environmental Management

Rapid urbanization is taking place especially in low-income countries. Globally, in 1985, 41%

of the world population lived in urban areas, and by 2015 the proportion is projected to rise to

60 % (Schertenleib, 1992). Of this urban population 68 % will be living in the cities of low-

income and lower middle-income countries (Figure 1).

4000000

20%

urban population (x1000)

3000000 12%

high-income countries

26% 23%

upper-middle-income countries

2000000

13% lower-middle-income countries

low-income countries

24%

1000000

45%

37%

0

1995 year 2015

Figure 1: Global urban population categorized by of different economies (Schertenleib, 1992). Economies

are divided according to 1996 GNP per capita: low income < 785 US$; low middle income 786-3115 US$;

upper middle income 3116-9635 US$, and high income > 9636 US$

(http://www.worldbank.org/data/databytopic/class.htm)

An important feature often cited when dealing with the urbanization of the developing world

is the rapid growth of cities and metropolitan areas. Between 1990-95 Asia's urban population

has grown at an average rate of 3.2 %, compared with just 0.8 % growth in rural areas. In

1994, 9 of 14 large urban agglomerations with a population of over 10 million people were

located in the Asia-Pacific region. Of the 369 cities in the world with more than 750'000

residents, 160 are in Asia and the Pacific (UNEP, 1999). Not only do these large urban

agglomerations represent an enormous challenge for environmental services. The global urban

data for the year 1995 (World Resources Institute, 1996) shows that approximately 65% of the

urban population in the developing world still live in cities with populations smaller than

750'000. Many of these "smaller" cities are facing urban environmental management

problems where appropriate approaches are sought now, before the cities' urban environments

deteriorate any further. The situation is even more acute, as data shows that slums are growing

at an alarming rate and as mentioned above it is especially in the urban poor areas where the

municipal solid waste management service is lacking behind the needs of the inhabitants

(UNEP, 1999).

2. The Elements of Asian Solid Waste Management Systems

The following chapter shall elaborate on some examples of solid waste management systems

as encountered in low-income Asian countries. The description does not mean to be complete

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 2

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

but intends to show some typical difficulties municipalities face and elucidate what innovative

solutions and approaches have been implemented.

A typical waste management system (figure 2) in a low-income Asian country can be

described by the elements:

Household waste generation and storage

Reuse and recycling on household level (includes animal feed and composting)

Primary waste collection and transport to transfer station or community bin

Management of the transfer station or community bin

Secondary collection and transport to the waste disposal site

Waste disposal in landfills

Recovering and recycling usually takes place in all elements of the systems and is widely

practiced by the informal sector "waste pickers" or by the solid waste management staff

themselves for extra income. Recovered and recyclable products then enter a chain of dealers,

or processing before they are finally sold to manufacturing enterprises.

Figure 2: Typical elements of a solid waste management system in low- or middle-income

countries (source: SANDEC/EAWAG)

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 3

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Waste Generation

Globally the per capita amounts of municipal solid waste generated on a daily basis varies

significantly. Economic standing is one primary determinant of how much solid waste a city

produces (World Resources Institute, 1996). Table 1 shows waste generation rates for some

Asian low- and middle income countries as cited in the literature.

Table 1: Waste generations rates of some Asian Countries, sorted by ascending Gross

National Income (GNI).

Country GNIa Waste generation Reference

[kg/capita day]

Nepal 240 0.2 - 0.5 (UNEP, 2001)

Cambodia 260 1.0 (Yem, 2001)

Lao PDR 290 0.7 (Hoornweg, 1999)

Bangladesh 370 0.5 (Hoornweg, 1999)

Vietnam 390 0.55 (Hoornweg, 1999)

Pakistan 440 0.6 - 0.8 (World Wildlife Fund, 2001)

India 450 0.3 - 0.6 (Ahmed, 2000; Akolkar, 2001)

Indonesia 570 0.8 - 1.0 (Mukawi, 2001)

China 840 0.8 (Hoornweg, 1999)

Sri Lanka 850 0.2 - 0.9 (Jayatilake, 2001; Hoornweg, 1999)

Philippines 1040 0.3 - 0.7 (World Bank, 2001)

Thailand 2000 1.1 (Hoornweg, 1999)

a

GNI 2000 per capita in $, based on Atlas Method, see http://www.worldbank.org/data/databytopic/class.htm

Although the table shows an increase of waste generation rates with higher GNI, it is

important to note that the ranges given are large. In most cases this reflects the large

differences between rural and urban areas. Waste generation figures cited in the literature are

often not commented further and thus do not allow precise interpretation of the value. Alkohar

(Akolkar, 2001) shows that waste generation rates in India vary in relation to the cities sizes.

The data shows average rates of 0.21 kg/cap day for cities between 100'000-500'000

population and 0.5 kg/cap day for cities larger than 5'000'000 population. Similar figures are

shown for Nepal (UNEP, 2001).

Waste Composition

Although countries sometimes use different categories for the physical characterization of

solid waste, the categories listed in Table 2 can usually be distinguished in the various waste

characterization studies. Not only wealth, but also consumer patterns significantly influences

waste composition.

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 4

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Table 2: Typical average waste characteristics in urban settings, sorted by descending

biodegradable waste fraction

Waste Categories (average percentage of wet weight)

City Bio- Paper Plastic Glass Metal Textiles & Inerts

degradable Leather (ash,

earth) &

others

Indonesia5 74 10 8 2 2 2 2

Dhaka2 70 4.3 4.7 0.3 0.1 4.6 16

Kathmandu1 68.1 8.8 11.4 1.6 0.9 3.9 5.3

Bangkok1 53 9 19 3 1 7 8

Hanoi1 50.1 4.2 5.5 2.5 37.7

Manila6 49 19 17 6 9

India4 42 6 4 2 2 4 40

Karachi3 39 10 7 2 1 9 32

1

(UNEP, 2001), 2 (Kazi, 1999), 3 (APE, 2001), 4 (Akolkar, 2001), 5 (Walhi, 2001), 6 (World Bank, 2001)

The high content of biodegradable matter and inert material, results in high waste density

(weight to volume ratio) and high moisture content. These physical characteristics

significantly influence the feasibility of certain treatment options. Vehicles and systems

operating well with low-density wastes such as in industrialised countries will not be suitable

or reliable under such conditions. Additionally to the extra weight, abrasiveness of the inert

material such as sand and stones, and the corrosiveness caused by the high water content, may

cause rapid deterioration of equipment. Wastes with a high water or inert content will have

low calorific value and thus also not be suitable for incineration.

Institutions and Partnerships in SWM

In many cities of Asia, deficiencies in the provision of waste services are the result of

inadequate financial resources, lacking management, and technical skills of municipalities and

government authorities to deal with the rapid growth in demand for service. Although budgets

are limited, the willingness to pay for well rendered services is high thus giving an

opportunity for appropriate approaches.

Local authorities of Asian cities (Asia Development Bank Institute, 1998) see their main

challenges as:

• unplanned growth and increasing pressure to provide services

• lack of adequate authority to address people, infrastructure and resourcing problems

• bureaucratic confusion and delays due to a multitude of agencies (local, provincial and

national level) operating within the same municipal boundaries

• lacking accountability

• limited communications within the city administration and more importantly between

the city administration and the various stakeholders

• political interference, as elected representatives often do not confine themselves to

strategic planning, policy setting and oversight of performance, but instead become

involved in daily operations

• lacking skills of municipal workforces, whereby training is often reserved to senior

staff and seen as a reward for good work and seen as a chance to break away from the

daily obligations

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 5

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

The situation in Delhi, India shows typical institutional deficiencies, faced by many urban

local bodies. "In the Municipal Corporation of Delhi, there are about 46'000 workers in solid

waste management. Only 33'000 are available in the field. The rest serve as domestic servants

at the residences of politicians. The absentee rate is 25%. The sanitary inspector, who

supervises them, knows about it but takes money from the worker and marks him as present"

(Ahmed, 2000).

There is a trend, sometimes driven by failing municipal systems or by pressure from national

governments and international agencies, to outsource the provision of services to the private

sector. "Public Private Partnerships (PPP)" is a term used for describing a variety of

relationships between public and private sector actors. In many countries private companies

are interested in providing solid waste management services and such partnerships are

successively implemented by the responsible authorities. In Chennai, a major port city in

Southern India, the French multinational Onyx won a contract with the municipal corporation

to collect the waste and sweep streets in one area of the city (Jayaraman, 2002). Remuneration

per ton of waste collected is significantly lower than the previous expenses of the

municipality and Onyx has won many praises from many residents for good service. An

important factor in the success of private sector participation is the ability of the municipal

administration to write and enforce an effective contract. The contract document must be well

written to describe in quantitative terms what services are required and to specify penalties

and other sanctions that will be applied in case of shortcomings. The ability and willingness

of the municipality to monitor the performance of the private partner and enforce sanctions if

necessary, are crucial for an effective partnership and for the long-term improvement of the

cities situation.

As an alternative to large (often multinational) companies, the local private sector, micro-

enterprises or small enterprises (MSEs), or even community-based organisations can also

provide much of the solid waste services for a city (Pfammatter, 1996 ; Haan, 1998). The

concept here is that waste management is seen as meeting citizens' needs therefore citizens are

entitled to transparency in decision making; Waste management is not merely a service

delivered by urban authorities but a cooperative undertaking that requires the coordination of

informal behaviours and conventional management approaches. With this concept, citizens

can perform some of the work, and people should assess the performance of municipal staff

and have the right to raise questions about decisions on, for instance, the siting of dumps and

transfer stations. Watchfulness and peer pressure of citizens is then also crucial to monitoring

solid waste management activities (UNEP-IETC, 1996).

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 6

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Figure 1: Primary waste collection by tricycle at a community-based scheme in Bangalore,

India

Well adapted to the local conditions such small scale approaches often use simple equipment

and labour-intensive methods, and therefore can collect waste in places where the

conventional trucks of the municipality or large companies cannot enter (figure 1).

Typical schemes often observed in Asian cities provide primary collection service (house to

house waste collection and transport to an intermediate collection point). Such primary

collection, often managed by community-based organisations or small enterprises, is often

initiated by the residents desperate need for a collection service for which the residents are

also willing to pay monthly collection fees. A recurring problem with such small scale waste

management schemes is that the waste usually needs to be handled by another entity – often

the municipality – from the intermediate collection point for further transport to the far away

disposal site. A solution is to recycle as much of the waste locally – with a decentralised

approach - so that there is very little need for on-going transport of collected waste.

In Indonesian cities municipal governments have introduced and promoted the concept of

organized citizen participation and involvement in primary collection schemes. In the city of

Yogyakarta for instance, such schemes - using handcarts for house to house collection - are

managed by the community or neighbourhood units and play a significant role in the city's

solid waste management system (Yayasan Dian Desa, 1993). Based on such existing schemes

further activities such as recycling of the organic fraction by composting have also been

initiated (Zurbrugg, 1999).

After five years of operating a neighbourhood waste collection and decentralised composting

scheme, the NGO Waste Concern in Dhaka, Bangladesh, has shown the great potential of

community-based decentralised approaches and finally convinced Dhaka's Municipal

Corporation and Public Works Department to provide government land on which they can

establish more community-based composting plants (Sinha, 2000). Government agencies

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 7

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

control the land and projects, while Waste Concern acts as the implementing agency. Eight

new community-based composting plants are being established throughout the city for a trial

period of one year and depending on the success of the composting units, the time period may

be extended. International donors have also recognised the potential of such approaches and

are supporting the implementation of such schemes in 14 cities of Bangladesh. Waste

Concern has been able to demonstrate how new approaches, in which non-governmental and

private sector enterprises work together with waste management authorities, can tackle the

serious problems of solid waste management.

In the city of Mumbai, India, community initiatives in solid waste management are currently

being supported by the municipal authorities. One initial successful scheme initiated by a

resident caught the interest of the Municipal Commissioner who wanted such schemes to be

replicated in other areas of the city. To this purpose he designated an "Officer on Special

Duty" to promote, and support what were then called Advanced Locality Management

schemes (ALMs). ALMs are formed streetwise or small area wise and consist of community-

based structures or neighbourhood initiatives. As support to these schemes the municipality

provides a platform for exchange and communication for ALM representatives and municipal

authorities. On one hand these are conducted on ward level with the municipal ward offices

every two weeks, and on the other hand on a monthly basis together with the Additional

Commissioner at the municipal headquarters. These meetings enable the residents to address

their area-related problems such as waste collection, road repair, lighting, water supply or

drainage problems in front of the municipal authorities. The chance to solve problems

together is regarded as a very important factor for developing social cohesion in the

neighbourhood. In addition, the municipality has organised 2-day workshops for each of the 6

city zones inviting various NGOs and Citizens Groups to discuss and exchange views with

municipal officers. Continuous support and a proactive approach to problem solving by the

Municipality is provided through a Municipal Junior Engineer assigned as "Nodal Officer" at

the section level. His function is to visit and interact with the ALMs on a regular basis. In

most cases, ALMs begin with an awareness and cleanup campaign. Waste collection and

street sweeping is often considered the priority focus and the first step in a good working

relationship between the municipal workers and the citizens. It is important to recognise that

the institutionally embedded structure of the ALM system sets the framework for such further

activities such as resource recovery and recycling.

Awareness and attitudes

Public awareness and attitudes to waste can affect the population's willingness to cooperate

and participate in adequate waste management practices. General environmental awareness

and information on health risks due to deficient solid waste management are important factors

which need to be continuously communicated to all sectors of the population. Participation of

the population can be by carrying waste to a shared container, by segregating waste to assist

recycling activities, or even if only by paying for waste management services. Some examples

of continuous education and awareness campaigns are the regular "Green and Clean"

campaigns to promote environmental awareness by the Metro Manila Women Balikatan

Movement and the Green Forum in Manila (UNEP-IETC, 1996). Another example is the

Environmental Pioneer Brigade Programme in Sri Lanka where children are made aware of

environmental problems, are shown how to manage the problems, or how to be preventative

so that the problems do not occur.

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 8

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Resource recovery and recycling activities

In many low-income Asian countries, recycling and recovery is usually conducted by the

informal sector on all levels of the waste management stream. Such work is done in a very

labour-intensive and unsafe way, and for very low incomes. The situation in industrialised

countries is very different, since resource recovery is undertaken by the formal sector, driven

by law and a general public concern for the environment, and often at considerable expense.

In the past the role of the informal sector in waste management has hardly been recognised by

the responsible authorities. Often the municipal authorities even actively hindered such

recycling activities. Now, more and more, the importance of recycling activities in reducing

waste volume and recovering resources and its economic benefits is being acknowledged.

In the Philippines a growing number of local governments are implementing integrated waste

management, which includes waste reduction, recycling, composting and re-use. Estimates

have shown that trade in waste materials has increased in volume by 39 % (World Bank,

2001). Some key factors that affect the potential for resource recovery are the cost of the

separated material, its purity, its quantity, and its location with regard to the intermediate and

final processing facilities. The costs of storage and transport are major factors that decide the

economic potential for resource recovery.

Composting is an excellent method of recycling biodegradable waste from an ecological point

of view. However, many large and small composting schemes have failed because not enough

attention was given to the marketing and the quality of the product. Current promising

developments can be observed in Bangladesh where local government authorities as well as

the Ministry of Agriculture is supporting and promoting composting and the use of compost

in agriculture. In India, the new solid waste legislation (Ministry of Environment and Forests,

2000) obliges municipalities to introduce household segregation of organic and non-organic

waste (called "wet" and "dry" waste respectively) and to treat the organic fraction by

composting or other appropriate means. Composting activities are becoming more and more

common as well as pilot plants for biomethanation of organic wastes, however the challenge

to establish a market and demand for the compost product has yet to be tackled.

Disposal

Open dumps - unfortunately still mostly observed in developing countries - where the waste is

dumped in an uncontrolled manner, can be detrimental to the urban environment. Many

governments now acknowledge the dangers to the environment and to public health derived

from uncontrolled waste dumping. However often officials think that uncontrolled waste

disposal is the best that is possible. Financial and institutional constraints are one of the main

reasons for inadequate disposal of waste, especially where local governments are weak or

underfinanced and rapid population growth continues. Many governments even have great

difficulties when trying to define their actual solid waste management costs, as very often no

detailed cost accounting is in place. When solid waste management systems based on user

fees are in place, often the fees only barely cover costs of collection and transport leaving

practically no financial resources for the safe disposal of waste. Financing this part of the

solid waste management cycle is made even more difficult as most people are willing to pay

for the removal of the refuse from their immediate environment but then “out of sight – out of

mind” are generally not concerned with its ultimate disposal.

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 9

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Over the years, due to rapid urbanisation, many existing disposal sites have been encircled by

settlements and housing estates. The environmental degradation associated with these dumps

directly affects the population with the consequence that disposal sites are subject to growing

public opposition. This, together with unavailability of land, is one of the reasons why

obtaining sites for new landfills is becoming increasingly difficult. Finding a site for a new

landfill far away from the urban area, may have the advantage of less public opposition.

However, it also means that the site is far away from the source of waste generation thus

increasing transfer costs and needing additional investments in the infrastructure of roads,

hence intensifying the financial problems of the responsible authorities.

Another reason for sustaining the current disposal practices are insufficient guidelines for

determining location, design and operation of new landfills, or for upgrading of old dumps.

Often the only guidelines and training materials available are those from high-income

countries. These are based on technological standards and practices suited to the conditions

and regulations of high-income countries and do not take into account the different technical,

economical, social and institutional aspects of developing countries. The responsible

authorities, seeing no other solution for their disposal situation, then start searching for waste

treatment methods like composting or incineration to alleviate their problems. Such treatment

methods however do not eliminate the need of a disposal site.

For the responsible authorities finding an ideal site, planning and designing a new landfill is a

lengthy and costly affair, often only feasible with external financial aid. In some major cities

loans or grants have been used to construct sanitary landfills1. However, if little attention is

paid to the training of a site manager and to the provision of sufficient financial and physical

resources to allow a reasonable standard of operation, the sites quickly degenerate into open

dumps.

Improving and "upgrading" waste dumps does not necessarily have to be difficult or

expensive. It should not be regarded as an alternative to a new site, but it can significantly

prolong the existing site's life span and reduce the negative environmental impact that in any

case would have to be dealt with when closing the site. Upgrading does not mean converting a

dump to a sanitary landfill in one step. Achieving a controlled, engineered landfill with a

minimal level of environmental pollution and health risk to the public (here defined as a

"sanitary" landfill), can be a step to step process depending on the financial situation of the

authorities. Such a step-wise approach should be supported in standards and legislation for

landfill disposal. The upgrading process can prolong the existing sites life span, giving the

responsible authorities time to engage in a serious siting procedure for a new landfill. As an

example of step to step improvement, the government of Malaysia formulated an action plan

in 1988 on the improvement of their disposal sites. When they considered the limited financial

resources and technical know-how that was available, the strategy adopted was to convert

open dumping to sanitary landfills in stages (Huri bin Zulkifli, 1993).

3. Conclusions

In Asian low- and middle-income countries, municipal managers still face many common

solid waste management problems. Although in some cities, successful innovative ideas and

approaches have been implemented on different levels of the solid waste management system

1

Sanitary landfills are disposal sites which are built and operated according to engineering principles in order to

minimise pollution of air, water and soil, and other risks to man and animals.

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 10

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

(from household storage to disposal), the know-how and experience is seldom communicated

and transferred to others with similar responsibilities. Rather many municipal officers go

through the same trial and error phases repeating mistakes made elsewhere before. Research

institutions, NGOs, and International agencies are seen as very important actors for enhancing

and supporting the dissemination of "best practices". It must be recognised, however, that

there is not a "package solution" for solving the solid waste problem. Although the

fundamental aspects of the waste management hierarchy (figure 2) remain valid, large

flexibility to use different approaches for different local situations and actively involving

residents at an early stage in planning and implementation are elements which have shown to

be most promising.

Figure 2: National and local factors (circular boxes) influencing the core concepts of the waste

management hierarchy (triangle) in which priority of solid waste elements diminish

from top to bottom (source: SANDEC/EAWAG).

Solid waste management is definitely not only a technical challenge. Understanding and

taking into account the environmental impact, financial and economic calculations, social and

cultural issues, and the institutional, political and legal framework, is most crucial for

planning and operation of a sustainable solid waste management scheme.

Bibliography

Ahmed, K., Jamwal, N., 2000. Garbage: Your Problem, Down to Earth: 30-45.

Akolkar, A. B., 2001. Management of municipal solid waste in India - Status and Options: An

Overview, In: Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Regional Workshop on Sustainable Waste

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 11

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Management, Singapore, October 8-10, 2002, German Singapore Environmental

Technology Agency (GSETA).

APE, 2001. The current and potential use of urban organic waste in Karachi - A market

analysis for composted municipal solid wastes, Unpublished Final Report, Association

for Protection of the Environment (APE), Karachi.

Asia Development Bank Institute, 1998. Report on the Mayors' Forum, In: Proceedings of the

Conference on Enhancing Municipal Service Delivery Capability, Cebu City,

Philippines, 2-4 December, Asia Development Bank Institute.

Haan, H. C., Coad, A., Lardinois, I., 1998. Municipal solid waste management. Involving

micro- and small enterprises. Guidelines for municipal managers, International Training

Centre of the ILO, Turin, Italy.

Hoornweg, D. T. L., 1999. What A Waste: Solid Waste Management in Asia, The

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, The World Bank.

Huri bin Zulkifli, Z., 1993. Improvement of Disposal Sites in Malaysia, Regional

Development Dialogue 14(No.3), 168-175.

Jayaraman, N.,2002.Trashing water is good business for water companies, CorpWatch India,

web-page, http://www.corpwatchindia.org/issues/PID.jsp?articleid=823.

Jayatilake, A., 2001. Sri Lanka's Strategies and Policies in Solid Waste Management, In:

Proceedings of the Asia Pacific Regional Workshop on Sustainable Waste Management,

Singapore, October 8-10, 2002, German Singapore Environmental Technology Agency

(GSETA).

Kazi, N. M., 1999. Citizens Guide for Dhaka - Capacity Building for Primary Collection in

Solid Waste, Environment and Development Associates (EDA) and Water, Engineering

and Development Centre (WEDC), Dhaka.

Kungskulniti, N., 1990. Public Health Aspects of a Solid Waste Scavenger Community in

Thailand, Waste Management & Research 8(2), 167-170.

Lohani, B. N., 1984. Recycling Potentials of Solid Waste in Asia through Organised

Scavenging, Conservation & Recycling 7(2-4), 181-190.

Ministry of Environment and Forests, 2000. Municipal Solid waste Managament and

Handling Rules, The Gazette of India. Part II - Section 3 - Sub-section (ii).

Mukawi, T. Y., 2001. Urban solid waste policy in Indonesia, In: Proceedings of the Asia

Pacific Regional Workshop on Sustainable Waste Management, Singapore, October 8-

10, 2002, German Singapore Environmental Technology Agency (GSETA).

Pfammatter, R., Schertenleib, R., 1996. Non-Governmental Refuse Collection in Low-Income

Urban Areas. Lessons Learned from Selected Schemes in Asia, Africa and Latin

America., SANDEC Report No. 1/96, Water and Sanitation in Developing Countries

EAWAG/Sandec.

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 12

Presented for: Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE)

Urban Solid Waste Management Review Session, Durban, South Africa, November 2002

Schertenleib, R., Meyer, W., 1992. Municipal Solid Waste Management in DC's: Problems

and Issues; Need for Future Research, IRCWD News (No. 26), Duebendorf, Switzerland.

Sinha, M. A. H. M., Enayetullah, I., 2000. Community Based Decentralized Composting:

Experience of Waste Concern in Dhaka, In: Proceedings of the Regional Seminar on

Community Based Solid Waste Management, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 19-20 February, 63-

78.

UNEP,1999.Global Environment Outlook, Geo-2000, UNEP,

http://www.grid.unep.ch/geo2000/english/0070.htm.

UNEP,2001.State of the environment 2001, http://www.eapap.unep.org/reports/soe/.

UNEP-IETC, HIID, 1996. International Source Book on Environmentally Sound

Technologies for Municipal Solid Waste Management, United Nations Environment

Programme (UNEP), International Environmental Technology Centre (IETC).

Walhi, J., 2001. A long way to zero waste management, In: Proceedings of the Waste-Not-

Asia Conference, Taiwan, 25-30 July 2001, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives

(GAIA).

World Bank, 2001. The Philippines Environment Monitor 2001, The World Bank.

World Resources Institute, United Nations Environment Programme, United Nations

Development Programme, The World Bank, 1996. World Resources 1996-97 - The

Urban Environment, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

World Wildlife Fund, 2001. Pakistan Country Report, In: Proceedings of the Waste-Not-Asia

Conference, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA). 25-30 July,Taiwan.

Yayasan Dian Desa, 1993. Study on Community-Based Primary Collection of Solid Waste, in

Indonesia, YAYASAN DIAN DESA Appropriate Technology Group Yogyakarta.

Yem, D., 2001. Solid Waste Management in Cambodia, In: Proceedings of the Asia Pacific

Regional Workshop on Sustainable Waste Management, German Singapore

Environmental Technology Aghency (GSETA).

Zurbrugg, C., Aristanti, C., 1999. Resource Recovery in a Primary Collection Scheme in

Indonesia, SANDEC News (No. 4), Duebendorf, Switzerland.

C. Zurbrugg, February 2003, USWM-Asia 13

You might also like

- Fundamentals of Urban and Regional PlanningDocument33 pagesFundamentals of Urban and Regional PlanningMaru Pablo75% (4)

- Waste to Energy in the Age of the Circular Economy: Best Practice HandbookFrom EverandWaste to Energy in the Age of the Circular Economy: Best Practice HandbookNo ratings yet

- Hyderabad - City Development Plan Chapter PDFDocument9 pagesHyderabad - City Development Plan Chapter PDFShivangi AroraNo ratings yet

- Week 4Document70 pagesWeek 4Manvi YadavNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management AssignmentDocument16 pagesSolid Waste Management AssignmentAlfatah muhumed100% (1)

- Municipal Solid Waste Management Challenges in Developing Countries - Kenyan Case StudyDocument9 pagesMunicipal Solid Waste Management Challenges in Developing Countries - Kenyan Case StudyMoe GyiNo ratings yet

- Zurbruegg 1998 LandfillDocument9 pagesZurbruegg 1998 LandfillNivea ZuniegaNo ratings yet

- What A Waste - A Global Review of Solid Waste ManagementDocument116 pagesWhat A Waste - A Global Review of Solid Waste ManagementrenodfbNo ratings yet

- New Rural Development Paradigm PresentationDocument28 pagesNew Rural Development Paradigm PresentationHeinzNo ratings yet

- Waste To Wealth by DR Sivapalan KathiravaleDocument26 pagesWaste To Wealth by DR Sivapalan Kathiravalekaitzer100% (1)

- Solid-Wastefinaldraft-12 29 15 PDFDocument62 pagesSolid-Wastefinaldraft-12 29 15 PDFDiana DainaNo ratings yet

- Solid Wastefinaldraft 12.29.15Document62 pagesSolid Wastefinaldraft 12.29.15Justine LagonoyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Climate Change On Urban Settlements in ColombiaDocument98 pagesImpact of Climate Change On Urban Settlements in ColombiaUrbanway100% (1)

- 3 Solid Waste 1.8Document55 pages3 Solid Waste 1.8Zinc MarquezNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management in Asian Countries: Problems and IssuesDocument11 pagesSolid Waste Management in Asian Countries: Problems and IssuesL M ArisonNo ratings yet

- AGC206Document10 pagesAGC206wong NXNo ratings yet

- Resettlement in China: Policy, Practice and Experiences: SHI Guoqing, ProfessorDocument81 pagesResettlement in China: Policy, Practice and Experiences: SHI Guoqing, Professorbhoj raj singalNo ratings yet

- 12 - Bongertmann T, Schoebiz L. Country Case TanzaniaDocument33 pages12 - Bongertmann T, Schoebiz L. Country Case TanzaniaaksalirkaNo ratings yet

- The Political Economy of Environmental Policy in Indonesia - PresentationDocument20 pagesThe Political Economy of Environmental Policy in Indonesia - PresentationADB Poverty ReductionNo ratings yet

- 3 Chapter 2 Literature Review PDFDocument53 pages3 Chapter 2 Literature Review PDFJohnlorenz Icaro de ChavezNo ratings yet

- Turner, Kerry - LITTORAL 2010 - The Role of The Coast in The Economy of NationsDocument19 pagesTurner, Kerry - LITTORAL 2010 - The Role of The Coast in The Economy of NationsjonlistyNo ratings yet

- AAG Philippine Solid Wastes Nov2017Document4 pagesAAG Philippine Solid Wastes Nov2017Gherald EdañoNo ratings yet

- SE07 - Solid Waste Management - SAPUAYDocument19 pagesSE07 - Solid Waste Management - SAPUAYKarl Lorenzo BabianoNo ratings yet

- Project/Programme ProposalDocument95 pagesProject/Programme ProposalPascal TebzaNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Management of Transboundary Waters in EuropeDocument37 pagesSustainable Management of Transboundary Waters in EuropeSafi HusseinNo ratings yet

- 354 1037 1 SMDocument8 pages354 1037 1 SMReynaldo LlameraNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management in Egypt: Section 2Document9 pagesSolid Waste Management in Egypt: Section 2Waled HantashNo ratings yet

- Lect-1 URBANISATION & TRANSPORTATION - SCENARIO, ISSUES AND STRETEGIESDocument28 pagesLect-1 URBANISATION & TRANSPORTATION - SCENARIO, ISSUES AND STRETEGIESDarshan DaveNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document2 pagesChapter 1Joshua SalazarNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 4 Waste Management Part I - Intro (New)Document23 pagesCHAPTER 4 Waste Management Part I - Intro (New)ainsahNo ratings yet

- Unit 2: The Global Situation: STAT101: Statistics in The Modern WorldDocument14 pagesUnit 2: The Global Situation: STAT101: Statistics in The Modern WorldAmna MazharNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXtoDocument11 pagesFULLTEXtoDEBANG EDCES R.No ratings yet

- Poverty and The Environment in Rural Cambodia: Tong Kimsun and Sry BopharathDocument13 pagesPoverty and The Environment in Rural Cambodia: Tong Kimsun and Sry BopharathMartha Jelle Deliquiña BlancoNo ratings yet

- Water Supply in EthiopiaDocument7 pagesWater Supply in EthiopiaKalu AbuNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id288963Document10 pagesSSRN Id288963A channelNo ratings yet

- Urbanization and Sustainability Challeng PDFDocument10 pagesUrbanization and Sustainability Challeng PDFFakhrul IslamNo ratings yet

- The Role of Waste To Energy (WTE) in A Circular Economy SocietyDocument35 pagesThe Role of Waste To Energy (WTE) in A Circular Economy SocietyJorge MartinezNo ratings yet

- Towards Zero Waste in Emerging Countries - A South African ExperienceDocument13 pagesTowards Zero Waste in Emerging Countries - A South African Experienceata radityaNo ratings yet

- Resources, Conservation and Recycling: Socio-Economic Profile and Profitability of Faecal Sludge Emptying CompaniesDocument8 pagesResources, Conservation and Recycling: Socio-Economic Profile and Profitability of Faecal Sludge Emptying CompaniesEddiemtongaNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste MGT IndiaDocument21 pagesSolid Waste MGT IndiaGopika GhNo ratings yet

- Presentation ResearchDocument8 pagesPresentation Researchapi-3698040No ratings yet

- How Inclusive Is The Growth in Asia and What Can Governments Do To Make Growth More Inclusive? (Presentation)Document9 pagesHow Inclusive Is The Growth in Asia and What Can Governments Do To Make Growth More Inclusive? (Presentation)ADB Poverty ReductionNo ratings yet

- Dryland Poverty: Characteristics, Policy Responses, New Challenges and Opportunities - PresentationDocument16 pagesDryland Poverty: Characteristics, Policy Responses, New Challenges and Opportunities - PresentationADB Poverty ReductionNo ratings yet

- Buku 2 PDFDocument17 pagesBuku 2 PDFSyafiq ShafieiNo ratings yet

- Angladesh Rofile: Sl. No. Items Bangladesh South Asia (Average) World (Average)Document2 pagesAngladesh Rofile: Sl. No. Items Bangladesh South Asia (Average) World (Average)raihan2235No ratings yet

- Republic of ChinaDocument18 pagesRepublic of Chinaapi-3696178No ratings yet

- NSWMC (2015)Document60 pagesNSWMC (2015)Hazel Ivy JeremiasNo ratings yet

- Plan WorkDocument5 pagesPlan Workbright osakweNo ratings yet

- Overview of DisastersDocument26 pagesOverview of DisastersYamang TagguNo ratings yet

- Real Estate in The PhilippinesDocument40 pagesReal Estate in The PhilippinesPurchiaNo ratings yet

- Chapter2 8 UrbanDocument30 pagesChapter2 8 Urbanlmary20074193No ratings yet

- Profile New ZealandDocument2 pagesProfile New Zealandjalhareem511No ratings yet

- 08 - Solid Waste Management - Part 1Document40 pages08 - Solid Waste Management - Part 12021301152No ratings yet

- Clean It Right - Dumpsite Management in IndiaDocument32 pagesClean It Right - Dumpsite Management in Indiasaravanan gNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - Municipal Waste Management PDFDocument17 pagesChapter 8 - Municipal Waste Management PDFlithaNo ratings yet

- Sustainable DevelopmentDocument33 pagesSustainable DevelopmentMadhukar JayantNo ratings yet

- Impact of Urbanization and Industrialization and Role of EIA On Sustainable DevelopmentDocument148 pagesImpact of Urbanization and Industrialization and Role of EIA On Sustainable DevelopmentAradhana Kanchan SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Municipal Solid Waste Management in Africa: Strategies and Livelihoods in Yaoundé, Cameroon - Waste ManagementDocument12 pagesMunicipal Solid Waste Management in Africa: Strategies and Livelihoods in Yaoundé, Cameroon - Waste ManagementNKWENTI DESHNICNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Moisture Content of Yola Municipal Solid WasteDocument13 pagesEvaluation of Moisture Content of Yola Municipal Solid WasteAbu MaryamNo ratings yet

- Governance, Environment, and Sustainable Human Development in Drc: The State, Civil Society and the Private Economy and Environmental Policies in Changing Trends in the Human Development Index After IndependenceFrom EverandGovernance, Environment, and Sustainable Human Development in Drc: The State, Civil Society and the Private Economy and Environmental Policies in Changing Trends in the Human Development Index After IndependenceNo ratings yet

- IncineratorDocument20 pagesIncineratorAndre Suito100% (2)

- Indo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignDocument6 pagesIndo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Landfills: The Future of Land Disposal of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW)Document29 pagesSustainable Landfills: The Future of Land Disposal of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW)Andre Suito100% (1)

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management Workshop Detail Design ImplementationDocument16 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management Workshop Detail Design ImplementationAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management MethodsDocument44 pagesSolid Waste Management MethodsAndre Suito78% (9)

- Solid, Toxic and Hazardous Waste: Cunningham - Cunningham - Saigo: Environmental Science 7Document42 pagesSolid, Toxic and Hazardous Waste: Cunningham - Cunningham - Saigo: Environmental Science 7Andre Suito100% (7)

- To The Methodology of The Investigation For A Sanitary Landfill SiteDocument27 pagesTo The Methodology of The Investigation For A Sanitary Landfill SiteAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management WorkshopDocument17 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management WorkshopAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Indo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignDocument6 pagesIndo-Manual of BiogasdigesterdesignAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopDocument27 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopAndre Suito100% (1)

- Evolution of Landfill Technology: South American ContextDocument57 pagesEvolution of Landfill Technology: South American ContextAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste MGT Technologies A FordeDocument23 pagesSolid Waste MGT Technologies A FordeAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Waste ManagementDocument29 pagesWaste ManagementAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Post Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopDocument32 pagesPost Asian Tsunami Waste Management Plan WorkshopAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Waste Management in IndiaDocument26 pagesWaste Management in IndiaAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Hazardous WasteDocument22 pagesHazardous WasteAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Desentralization Waste MNGMT in VietnamDocument27 pagesDesentralization Waste MNGMT in VietnamAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Zrotary Clean & GreenDocument15 pagesZrotary Clean & GreenAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Unfcc-Green House TrainingDocument122 pagesUnfcc-Green House TrainingAndre Suito100% (1)

- Indonesia CDM ProjectDocument19 pagesIndonesia CDM ProjectAnh DNNo ratings yet

- Manual of Sanitary Landfill Permits and AprovalDocument142 pagesManual of Sanitary Landfill Permits and AprovalAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Urbanisation and Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Case Study of MumbaiDocument15 pagesUrbanisation and Municipal Solid Waste Management: A Case Study of MumbaiAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Ina - Emisi Gas Di IndonesiaDocument14 pagesIna - Emisi Gas Di IndonesiaAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Solid Waste Management in Indian Ocean Islands & SeychellesDocument15 pagesSolid Waste Management in Indian Ocean Islands & SeychellesAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Landfills: Remediation of Former Dumpsites AND Design of Engineered LandfillsDocument19 pagesLandfills: Remediation of Former Dumpsites AND Design of Engineered LandfillsAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- SC of Recycle PaperDocument160 pagesSC of Recycle PaperAndre Suito100% (1)

- Report of Kalimantan Urban Dev ProjectDocument91 pagesReport of Kalimantan Urban Dev ProjectAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- 3R Implementation in Indonesia Asia 3R ConferenceDocument20 pages3R Implementation in Indonesia Asia 3R ConferenceAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- SC of Conrad - Britannia - LandfillDocument33 pagesSC of Conrad - Britannia - LandfillAndre SuitoNo ratings yet

- Book of Asesment Info About WasteDocument63 pagesBook of Asesment Info About WasteAndre Suito100% (1)