Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Food Policy Reforms: A Rapid Tour of Possibilities

Food Policy Reforms: A Rapid Tour of Possibilities

Uploaded by

vinitgOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Food Policy Reforms: A Rapid Tour of Possibilities

Food Policy Reforms: A Rapid Tour of Possibilities

Uploaded by

vinitgCopyright:

Available Formats

Food Policy Reforms: A Rapid

Tour of Possibilities

Bharat Ramaswami

IGIDR Silver Jubilee International

Conference

December 1-3, 2012

Collaborators

Milind Murugkar

Ashok Kotwal

Pulapre Balakrishnan

A Rare Moment?

Food policy institutions have enjoyed stability and continuity for

decades despite changes in scale and objectives

The public distribution system (PDS): origins in WW II rationing

systems.

The Food Corporation of India (FCI) the Central government

agency responsible for procurement and storage was set up in the

mid-60s.

Practice of offering support prices to rice and wheat also dates from

that period.

At this moment, though, Indias food policy is in a state of flux.

Real possibility that Indias food policy institutions may look quite

different in a decade.

Pressures on Food Policy

Stunning GDP growth but only modest dent in

poverty.

Contradiction hard to ignore politically

The National Food Security Bill at the Central

level

Several food policy reforms at the State

government level.

Civil Society activism among other things they

have demanded and obtained judicial oversight

of the States food intervention.

The neo-classical economics case for

food policy interventions

Price supports and procurement

Absent risk markets, price supports can be Pareto

improving. Producers gain from insurance against low

price outcomes. Consumers gain too: the supply

response to price insurance lowers food prices (Innes,

QJE, 1990)

Subsidised food distribution to the poor

Traditionally, justified with reference to equity

objective.

A small literature now on growth impacts of safety

nets (Alderman and Yemetsov, 2012)

Other instruments: open market sales,

public stocks?

In the Indian context, it can be argued that these

are the outcomes of price supports and

subsidized food distribution.

Open market sales occur fitfully and almost

always to dispose off excess stocks. There is no

announced protocol for these sales.

Although there are announced norms for public

stocks, these are driven mostly by the needs of

the public distribution rather than market

stabilization.

Price supports in Practice

Price supports supplanted by administered

prices and procurement.

The farm lobby and its hold

Counter-moves by the government to reduce the

cost of procurement by restrictions on exports

and other private sector activity

Has bolstered the profitability of the grain sector

distorting crop choice and diversification

Unsustainable environmentally (e.g., paddy

production in Punjab)

Subsidised food distribution in practice

Identifying the poor has been difficult

Drawing a line in the sand!

Massive exclusion of the poor both exogenous and

endogenous.

Illegal arbitrage between the PDS and the market

Rent seeking and political patronage of PDS dealers

Unviable government marketing chain (PDS) volumes

insufficient to justify the costs.

This has encouraged illegal diversion, limited and

unpredictable service timings and customer unfriendly

practices.

Facts are never enough!

Practically no disagreement about how

procurement and subsidized food distribution

work in practice.

But there are very different views about what

to do next.

The Tower of Babel: what do we do

next?

Policy advise from economists, multi-lateral

institutions: target subsidies, make state

agencies open to competition, include private

sector

Pressure from activists, NGOs: Make subsidies

universal, no private sector, empower

communities and enact laws to make the state

accountable.

Government speaks in many voices: axe of fiscal

consolidation, social justice, farmer rights,

consumer interests

The imbalance in the practice of food

policy (Peter Timmer, 2008)

When politics is in command, which seems to

be the normal state of affairs for most developing

countries, how do efficiency issues stay on the

agenda?

When markets are in command, which seems

to be the main policy advice from the donor

community in poor countries, how do

distributional and welfare issues stay on the

agenda?

Can we have only one or the other?

PDS Forever? (Kotwal, Murugkar and

Ramaswami, 2011)

Balance between politics and markets.

Food subsidies ought to be near universal.

Targeting is hard to do when there are so many

just above the poverty line. Exclusion errors

bound to happen.

Therefore, tolerate the leakage of resources to

the non-poor.

Among other things, use markets in the form of

cash transfers to reduce diversions and other

waste.

No reason to tolerate such leakage of resources.

In the remainder of this talk.

Will not pursue further the issues of balance

between politics and markets with respect to

the grand design of food policy.

Use this perspective to assess the prospects of

`incremental reform in (a) storage and

procurement and (b) distribution.

Storage

Since 2010, the problem of insufficient storage

capacity has attracted both political and

media attention.

Article1-578444.aspx.htm

142399.html

31386742_1_lakh-tonnes-fci-and-state-

central-pool.htm

So how bad is the shortfall in capacity?

Seasonal storage

Crop harvests occur at finite discrete points

(once or twice during a crop year) while

consumption is continuous.

Hence the crop needs to be carried from

harvest to the other months when there is no

harvest. This is the demand for seasonal

storage.

No seasonal pattern in grain

consumption

Quarter All grain Rice Wheat All grain Rice Wheat

Per capita & per month,

Kg

Index with July-

September = 100

July-September 11.7 6 4.32 100 100 100

October-December 11.55 5.9 4.16 96.29 96.3 96.3

January-March 11.58 5.99 4.08 94.27 94.3 94.3

April-June 11.44 5.94 4.38 101.35 101 101

Seasonal demand for storage

Principle: Grain must be equally allocated

over time.

Application

1. Compute marketed surplus

2. Assume that the portion consumed on-farm

does not require commercial storage

3. No carry-overs of grain across marketing years

(only seasonal storage considered).

4. In the harvest periods, consumption demand is

instantaneously met without any storage. Of

course some temporary storage is required but

that could be in shops, transit or out in the

open.

Quarter-wise demand for storage

Rice Wheat Total

July 1 12.5 30 42.5

Oct 1 0 20 20

Jan 1 38.5 10 48.5

April 1 25 0 25

Marketed surplus of rice =

50 mill tons

Marketed surplus of wheat

= 40 mill tons

Oct 1, Kharif marketing

year: start with zero rice

stocks

Jan 1 = 3/4

th

of 50 = 38.5

April 1 = of 50 = 25

July 1 = 1/4

th

of 50 = 12.5

Storage capacity

Peak seasonal storage demand occurs on Jan 1

and this is the capacity that needs to be created =

50 million tons.

Such a calculation can be worked out for any

other estimate of production and marketed

surplus.

For e.g., projection for 2013/2014 53 m tons of

rice and 43 m tons of wheat.

Implies peak storage demand of (3/4*53+1/4*43)

Demand for Public Stocks under the

National Food Security Bill

Scenari

os Total

Procurem

ent

Rice

procurem

ent

Wheat

procurem

ent

Rice

storage

on Jan 1

Wheat

storage

on Jan

1

Total

storage

on Jan

1

1

64 38.4 25.6 28.8 6.4 35.2

2

74 44.4 29.6 33.3 7.4 40.7

Implications

Calculations suggest that peak seasonal

storage demand is of the order of 41 million

tons in the immediate future.

As rice procurement takes place across both

Oct-Dec and Jan-March quarter, above

estimate is an upper demand.

To this add, the emergency reserve

requirement for annual storage = 47 million

tons.

Supply-Demand gap

Policies emphasize the urgency of creating

more storage.

The gap between supply (32 mt) and

estimated demand (47 mt) is about 15 million

tons.

Yet even 47 mt is not sufficient today when

peak stocks top 70 mt. So what is wrong with

out calculations?

Supply-demand gapII

Our calculations assumed that procurement

would match the PDS commitments to

distribution.

This may not happen: procurement may

outstrip requirements as has been the case for

nearly 2 decades.

Procurement larger than PDS sales

Why excess procurement?

Procurement larger than PDS sales. No stabilization

Why? Farm lobby and coalition politics??

Other reasons: Suppose the central government only

wants to buy enough to meet PDS requirements. Then

the problem is: what is the right procurement price

that elicits the required quantity?

Politicians and bureaucrats fear the embarrassment of

under-supplying the PDS but receive no penalty for

excess stocks and high prices. Works to strengthen the

farm price lobby.

Bias in favour of higher than necessary procurement

prices and therefore large procurement.

Mistakes endure

Once stocks are large, private traders withdraw and

procurement continues to be high in successive years

(even without high procurement prices)

This cycle has only been broken by droughts, exports

(often subsidised), and ad-hoc sales through the PDS

and the market.

An increase in scale of the PDS together with legal

obligations to keep the PDS supplied will amplify the

tendency to play safe.

Under NFSB, a continuation of present procurement

policies could result in excess stocks even higher than

what is seen today.

What can be done?

Open market sales

Basu (2010) proposed a mechanism of selling grain in

small batches to many traders and consumers to

maximise the impact of open market sales on price.

Basus proposal was made in the context of market

stabilizing intervention where procurement varies

according to available supplies.

But as we have seen, Indian intervention has been

systematically biased towards subtracting supplies.

So the first best policy is to reduce procurement.

Policy options

Reform procurement from being open-ended to closed-

ended.

This may be politically difficult.

Incremental reform proposal create a new agency under

the CACP called the Risk Management Agency (RMA).

Let the FCIs liability be limited to the grain purchased for

PDS.

Stocks in excess will be transferred to the books of RMA.

This will (a) make excess stocks visible and (b) force the

office of CACP to take this into account in recommending

procurement prices!

Part II Distribution Reforms

The distribution of food subsidies happens within

a federal structure.

Central government: largely responsible for

funding, procurement and transport of grain to

the States

States: responsible for implementation and

delivery of food subsidies

Distribution reforms have to be understood with

reference to initiatives at the Centre as well as

with the States.

We report on some state-level reforms

Principal elements of distribution

reforms

1. Computerizing the data base of beneficiaries

2. New listing of beneficiaries

3. Issue of new ration cards incorporating bar-

coding and biometric id

4. Authentication of transactions by smart cards

and/or biometric id.

5. Recording of transactions in real time or

near-real time through IT systems.

Use of IT systems in recording data is a

major distribution reform

Automation of retail transactions leads to real time

information on supply gaps at each retail outlet.

Hence, it is possible to connect this module with a

back-end module of inventory management system

(stocks and grain movement between different storage

depots) resulting in automated supply and movement.

This reduces paperwork and increases the timeliness

and predictability of supplies.

This is the major reform of PDS in the state of

Chhatisgarh

Authentication of transaction is a

major distribution reform

Illegal diversion of grain: arbitraged grain is

recorded as sold at the issue price in government

records.

This is possible to do when the sales are to

fictitious consumers. Multiple ration cards may

be held by a single consumer or ration cards may

be `bogus.

This can only be stopped if the retail transaction

is authenticated in a fool-proof manner.

This is the major distribution reform being

attempted in Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat

Authentication by Smart cards

With or without biometric id (like bank cards with a

numeric code id).

Requires the use of smart card readers at the retail

level connected to a central server.

Connectivity at all FPS may be a problem.

Pilot project in Chandigarh where the infrastructure is

reasonable.

However, record is mixed because of failure of smart

card readers.

Smart card based authentication proposed for big

urban centres of Chhatisgarh.

Biometric ID

If employed at the retail level, it is subject to

the same limitations as smart cards (without

biometrics) namely connectivity and the

possibility of `engineered device failure.

Intermediate system: Use biometric id at

select offices to obtain food coupons which

are then redeemed at the FPS.

Connectivity is not required at all retail points.

Costs of distribution reform

Reported costs are often incomplete because

of `zero-price transactions between

government agencies.

MP model: all activities out-sourced to a

private consortium for 5 years.

Cost = Rs. 4611 million or Rs. 461 crores.

Individual State Experiences:

Chhattisgarh

Computerization of Procurement system under

the decentralized procurement scheme.

Timely management of supplies because of

computerization and control over supplies (not

dependent on FCI for grain movement to state).

`Door-step delivery

No transaction authentication mechanism

smart card based solution (without biometrics

proposed for urban areas).

Chhattisgarh

Extended coverage: 70% of population under

BPL/AAY. Low exclusion errors.

Lower BPL rates: Rs. 2 for rice and Rs 1 for AAY

State spends significant resources over Rs.

1000 crores in addition to Central subsidy

De-privatization of FPS: Shops are run by

community organizations: self-help groups,

panchayats and coops. Such experiments

have not worked elsewhere.

Chhattisgarh

Low prices, extended coverage and well

publicised timely supply have worked to

create public consciousness about the right to

receive PDS entitlements. This is claimed to

have checked illegal diversions.

Chhattisgarh: Implications?

Supporters claim that (near) universal coverage

and de-privatization of FPS is responsible for

success and can be replicated elsewhere.

Several unique features

Willingness to spend out of its resources high

political commitment

Bureaucracy is unusually pro-active in monitoring the

supply chain. This is essential because the incentives

for arbitrage continue to be present.

Neither can be taken for granted elsewhere because

of entrenched interests in existing PDS

Gujarat

Encompasses all 4 components of distribution

reform.

Pilot project of reform: one FPS in each taluka

of 22 districts are participating.

Gujarat Model: A Food Coupon Model

All households to re-register to obtain bar-

coded ration cards. All household particulars

digitised and biometrics recorded.

Enrollment in this process requires an

electoral photo ID.

Using the bar-coded ration cards, beneficiary

visits an E-kiosk (in gram panchayat during

pilot).

Gujarat Model 2

Computer operator uses a bar code reader to

enter beneficiary details. On verification of

biometrics, bar coded food coupons issued.

Biometric verification requires real time

connectivity.

Beneficiary redeems coupons at designated

FPS.

FPS retailer submits these coupons at E-Kiosk

to be read into an electronic sales register.

Gujarat Model 3

Back-end inventory management system

linked with distribution network is in the

works.

IT solutions developed by NIC and in-house

team.

Modest capital costs of Rs. 800 million and

recurring costs of Rs. 250 million. However,

this does not include NIC costs.

Gujarat model: Assessment

Transaction authentication is the focus and the

strength of the model.

Weakness

Requires consumers to make 2 visits monthly the E-

kiosks are often more distant.

Internet connectivity is not yet good enough the two

visits could stretch to more

Problem could be less acute if coupons were issued

annually or bi-annually.

Requirement of electoral ID is bound to exclude some

of the poor.

MP Model

Similar to Gujarat in intent and scope.

But different in terms of design and execution.

Further MP is not at a pilot-stage but at a roll-

out stage.

Biometric id is at the heart of the MP model.

Designed to be compliant with Aadhar, the

nation wide biometric id project.

MP Model 2

Aadhar enrollment is a pre-requisite for PDS.

Camps organized in villages for Aadhar

enrollment.

Enrollment used to create a new

computerized data base of PDS beneficiaries

and to the issue of new Aadhar based ration

cards.

Food coupons couriered annually to

beneficiaries.

MP Model 3

Biometric id verified on receipt with portable

devicies using GPRS connectivity of cell phone

networks.

Beneficiary redeems coupons at FPS.

Redeemed coupons picked up and transported to a

central high speed scanning centre.

On coupon verification, electronic system generates

a report of transaction and sales which can be used

for allotment, supplies and movement

Execution

Execution outsourced to a private consortium.

No capital costs for government; pays Rs. 10.98

per transaction.

Strengths of model

Transaction authentication

Avoided the smart card route which is demanding of

infrastructure and which is prone to sabotage.

Zero upfront costs for government all risks of project

implementation with consortium.

Incentives of vendors aligned with customers.

Challenges to MP Model

Will enrollment leave out many of the eligible?

And how easy will be for them to subsequently

enroll?

Reliance on Aadhar: Issue of ids is not keeping

pace with enrollment.

Will the real-time verification of Aadhar id work?

MP model does not yet include computerization

of procurement and storage (unlike

Chhattisgarh).

MP and Gujarat model different from

the Direct subsidy model

Direct subsidy model championed by the Task Force on

Direct transfers.

Here the grain (or the subsidised commodity) flows through

the government marketing chain at market prices.

So no incentive for leakage.

Consumer buys from authorised retailer at market prices.

The retail transaction is subject to aadhar id verification

and is linked to a payments system.

This link transfers the subsidy directly to the beneficiarys

account.

The direct subsidy model requires devices to capture

biometric id and transaction at the retail level while the

coupon model needs it only when the coupons are issued.

Summary Findings I

We are short of storage capacity

Extent of shortfall would be less if

procurement were to be in line with

distribution.

While this might be difficult to implement

straightaway, it should be possible to devise

new institutional structures to make `excess

stocks visible.

Summary Findings II

Distribution reforms have enormous potential

because most states are starting at a high level

of inefficiency.

While these reforms have wide support, the

entreched interests in unreformed PDS are

strong and political commitment in the States

cannot be taken for granted even if it allows

reforms to be initiated.

Summary Findings III

Distribution reforms hold the promise of

accountability and transparency.

Computerizing the supply chain and digitising

records are low-hanging fruit.

Transaction authentication is more demanding

but with higher payoffs too.

Summary Findings IV

Smart card based systems are not practical at this point.

Intermediate systems such as food coupons based on

biometric id are more practical perhaps even more so

than the direct subsidy transfer model of the Central

government.

It is imperative therefore to allow and experiment with

different models.

The question is how to design them without imposing

additional costs of access on poor consumers.

You might also like

- Agricultural Marketing ManagementDocument18 pagesAgricultural Marketing ManagementTapesh AwasthiNo ratings yet

- Harvard ManageMentor Series DescriptionDocument10 pagesHarvard ManageMentor Series Descriptionndxtraders100% (1)

- Beauty StandardsDocument10 pagesBeauty StandardsBet TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- University of Sunderland Programme: Individual AssignmentDocument17 pagesUniversity of Sunderland Programme: Individual AssignmentZiroat ToshevaNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan For Grade 10 Physical EducationDocument6 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan For Grade 10 Physical EducationKim Sheene Acero86% (7)

- Food SecurityDocument21 pagesFood SecurityMd Shahnawaz Islam100% (2)

- Macroeconomics: Food Security Bill and Current AffairsDocument9 pagesMacroeconomics: Food Security Bill and Current AffairsSimran KhanNo ratings yet

- History of Food Security Policy in IndiaDocument4 pagesHistory of Food Security Policy in IndiaJatin351No ratings yet

- Agricultural ReformsDocument24 pagesAgricultural ReformsAnkita baroNo ratings yet

- Agr. Eco.04Document44 pagesAgr. Eco.04Muse IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Aec 401 Food Security Lecture Slides-1Document24 pagesAec 401 Food Security Lecture Slides-1Adeolu AlagbeNo ratings yet

- Development Strategies in IndiaDocument79 pagesDevelopment Strategies in IndiaSachin KirolaNo ratings yet

- Agr. Eco.06Document39 pagesAgr. Eco.06Anonymous MH2ORWmxENo ratings yet

- Economics Lesson 4 Form 4Document9 pagesEconomics Lesson 4 Form 4tyliqueantoineNo ratings yet

- Ramesh Singh Indian Economy Class 16Document55 pagesRamesh Singh Indian Economy Class 16Abhijit NathNo ratings yet

- Agriculture Procurement Buffer Stock FCI Reforms and PDS PDFDocument10 pagesAgriculture Procurement Buffer Stock FCI Reforms and PDS PDFAshutosh JhaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 03 - SharedDocument38 pagesLecture 03 - SharedKRIPI BADONIANo ratings yet

- Agricultural PricingDocument21 pagesAgricultural PricingPrince RathoreNo ratings yet

- rREFORMS IN AGRI - LEC 3Document13 pagesrREFORMS IN AGRI - LEC 3NewVision NvfNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics Mod1Document22 pagesManagerial Economics Mod1anon_732278444No ratings yet

- Basic Problemd of An EconomyDocument11 pagesBasic Problemd of An EconomySparsh JoshiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Essentials of EconomicsDocument28 pagesChapter 2 - Essentials of EconomicsloubnaNo ratings yet

- Irteza Rashid-Transaction Cost and BargainingDocument24 pagesIrteza Rashid-Transaction Cost and BargainingA K M Samiul Masuk SarkerNo ratings yet

- Procuremet Storage DetailsDocument4 pagesProcuremet Storage DetailsGowri NandaNo ratings yet

- Lecture1. IntroDocument25 pagesLecture1. IntroMochiiiNo ratings yet

- Managerial 1Document88 pagesManagerial 1Mary Kris CaparosoNo ratings yet

- Lec-1 (Microconomics)Document32 pagesLec-1 (Microconomics)arif571512No ratings yet

- Introduction To The Section HeDocument38 pagesIntroduction To The Section Heapi-87967494No ratings yet

- TOPIC: Industry Analysis of FMCG Industry With Specific Reference To Dabur India LTDDocument12 pagesTOPIC: Industry Analysis of FMCG Industry With Specific Reference To Dabur India LTDNaina BakshiNo ratings yet

- IED CH 2 Part 1Document19 pagesIED CH 2 Part 1Prachi SanklechaNo ratings yet

- PARLEDocument16 pagesPARLESaurabh SinghNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Business Economics: Session I and 2Document21 pagesIntroduction To Business Economics: Session I and 2Vignesh LakshminarayananNo ratings yet

- Economics Food Security in IndiaDocument2 pagesEconomics Food Security in Indiadivishachauhan473No ratings yet

- Asignemt Final Agric.. 2003Document9 pagesAsignemt Final Agric.. 2003samkappiNo ratings yet

- Presentation-Group 2Document24 pagesPresentation-Group 2Ramos, Keith A.No ratings yet

- 108INUNIT3A Sectoral Composition of Indian EconomyDocument95 pages108INUNIT3A Sectoral Composition of Indian EconomyDr. Rakesh BhatiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Rural DevelopmentDocument23 pagesChapter 6 Rural Developmentgaming rawatNo ratings yet

- Central ProblemsDocument7 pagesCentral ProblemsMaryam SiddiqueNo ratings yet

- Issues in Food Security BillDocument23 pagesIssues in Food Security BillShailu SharmaNo ratings yet

- Managerial EconomicsDocument222 pagesManagerial EconomicsSherefedin AdemNo ratings yet

- Food InflationDocument34 pagesFood Inflationshwetamohan88No ratings yet

- Week5 Monday SlidesDocument31 pagesWeek5 Monday SlidesSiham BuuleNo ratings yet

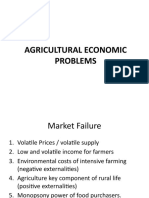

- Agricultural Economic ProblemsDocument23 pagesAgricultural Economic ProblemsRiska FadilaNo ratings yet

- Oxfam - Power, Rights and Inclusive MarketsDocument16 pagesOxfam - Power, Rights and Inclusive MarketsAndrea FurNo ratings yet

- C1. Buffer StockDocument4 pagesC1. Buffer Stockjaitun tutiNo ratings yet

- Economic Planning1Document2 pagesEconomic Planning1Anonymous dG26UpGc4No ratings yet

- An Assessment of Implementing of Minimum Support Price For Ragi - A Case of Rural Mysore Supradesh Vs Batch: GPBL-B/OCT10/30/IGDocument14 pagesAn Assessment of Implementing of Minimum Support Price For Ragi - A Case of Rural Mysore Supradesh Vs Batch: GPBL-B/OCT10/30/IGSupradesh VsNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document34 pagesCH 1dessie adamuNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3-Comparative Economic PlanningDocument28 pagesLesson 3-Comparative Economic PlanningSanjanaDostiKarunggiNo ratings yet

- Food Production - GeogrpahyDocument12 pagesFood Production - GeogrpahyFrancis OdoomNo ratings yet

- Constraints in Agricultural MarketingDocument36 pagesConstraints in Agricultural MarketingKIRUTHIKANo ratings yet

- To Combat Food Price Inflation in Your Opinion Should FDI in Multi Brand Retail Be Allowed or Disallowed? Please Support With Logic and No If NeededDocument3 pagesTo Combat Food Price Inflation in Your Opinion Should FDI in Multi Brand Retail Be Allowed or Disallowed? Please Support With Logic and No If NeededArjun SinghNo ratings yet

- Session 16: Understanding Economics and How Its Affects BusinessDocument36 pagesSession 16: Understanding Economics and How Its Affects BusinessJennifer CarliseNo ratings yet

- Unit 1-ADocument37 pagesUnit 1-Aobodyqwerty123No ratings yet

- Agricultural Marketing - Powerpoint PresentationDocument36 pagesAgricultural Marketing - Powerpoint PresentationBasa Swaminathan0% (1)

- Week 1 - MACRODocument34 pagesWeek 1 - MACROJohn Robert ReyesNo ratings yet

- Agriculture 11Document18 pagesAgriculture 11Mayank BahetiNo ratings yet

- Week 01-The Fundamentals of EconomicsDocument33 pagesWeek 01-The Fundamentals of EconomicsPutri WulandariNo ratings yet

- Ch. 6 Introduction To Islamic Microeconomics (Fitri Yani Jalil)Document30 pagesCh. 6 Introduction To Islamic Microeconomics (Fitri Yani Jalil)FitriNo ratings yet

- Government Intervention and Government FailureDocument10 pagesGovernment Intervention and Government Failureharshalshah3110No ratings yet

- Chapter One AgriDocument54 pagesChapter One Agriermiyas tesfaye100% (1)

- Ramesh Singh Indian Economy Class 17Document66 pagesRamesh Singh Indian Economy Class 17Abhijit NathNo ratings yet

- 6.3 Assignment Mohammed ObaidullahDocument10 pages6.3 Assignment Mohammed ObaidullahGPA FOURNo ratings yet

- Food Trend Concepts: Vertical Farming, Sustainability, Quality Control Fresh Produce Industry, Local Production, Exotic Fruits, Seaweed-based Packaging, Postharvest CoatingsFrom EverandFood Trend Concepts: Vertical Farming, Sustainability, Quality Control Fresh Produce Industry, Local Production, Exotic Fruits, Seaweed-based Packaging, Postharvest CoatingsNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary: Table 1: Number of Recognized Schools in IndiaDocument3 pagesExecutive Summary: Table 1: Number of Recognized Schools in IndiavinitgNo ratings yet

- Puja Checklist: PreparationsDocument2 pagesPuja Checklist: PreparationsvinitgNo ratings yet

- Aaker Kumar Day Ch24Document20 pagesAaker Kumar Day Ch24vinitgNo ratings yet

- IIMB Term1 PGP Chapter1Document33 pagesIIMB Term1 PGP Chapter1vinitgNo ratings yet

- Proof of ChebechevDocument1 pageProof of ChebechevvinitgNo ratings yet

- Acute Pharyngitis in Children and Adolescents - Symptomatic Treatment - UpToDateDocument18 pagesAcute Pharyngitis in Children and Adolescents - Symptomatic Treatment - UpToDateJosué Pablo Chicaiza AbadNo ratings yet

- La Civilta Cattolica 15 July 2020Document128 pagesLa Civilta Cattolica 15 July 2020Tetiana BogoslavetsNo ratings yet

- 5 Key ConceptsDocument9 pages5 Key Conceptskashif KASHIF .No ratings yet

- From Hierarchy To Anarchy - Larkins PDFDocument279 pagesFrom Hierarchy To Anarchy - Larkins PDFMartina Marty100% (1)

- Amphibia-Parental CareDocument4 pagesAmphibia-Parental CareAakash VNo ratings yet

- SentinaDocument10 pagesSentinaakayaNo ratings yet

- Walter Benjamin: Submitted To Respected Dr. Asma Aftab Presentation by Fauzia Amin PHD ScholarDocument37 pagesWalter Benjamin: Submitted To Respected Dr. Asma Aftab Presentation by Fauzia Amin PHD ScholarAnila WaqasNo ratings yet

- Six-Month Neuropsychological Outcome of Medical Intensive Care Unit PatientsDocument9 pagesSix-Month Neuropsychological Outcome of Medical Intensive Care Unit PatientsYamile Cetina CaheroNo ratings yet

- Merged 20240425 1313 RemoDocument4 pagesMerged 20240425 1313 Remodeep925211No ratings yet

- HH HTDocument3 pagesHH HTHoàng Thuỳ LinhNo ratings yet

- TSCM50 SummarizedDocument49 pagesTSCM50 SummarizedrohitixiNo ratings yet

- Sythesization and Purification of Acetanilide by Acetylation and Re CrystallizationDocument4 pagesSythesization and Purification of Acetanilide by Acetylation and Re CrystallizationToni Sy EncinaresNo ratings yet

- Rudrabhisheka-Stotram Kannada PDF File2011Document3 pagesRudrabhisheka-Stotram Kannada PDF File2011Praveen AngadiNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Severability and Doctrine of Eclipse Laws Inconsistent With or in Derogation of The Fundamental Rights (Article 13)Document19 pagesDoctrine of Severability and Doctrine of Eclipse Laws Inconsistent With or in Derogation of The Fundamental Rights (Article 13)kirti gargNo ratings yet

- CIVL-365 Tutorial 8 - 2021Document3 pagesCIVL-365 Tutorial 8 - 2021IvsNo ratings yet

- Maruti Suzuki Corp ComDocument10 pagesMaruti Suzuki Corp ComTANISHQ KATHOTIANo ratings yet

- NCRD's Sterling Institute of Management Studies, Nerul, Navi MumbaiDocument11 pagesNCRD's Sterling Institute of Management Studies, Nerul, Navi MumbaiAditya DetheNo ratings yet

- From Worry To Worship ExcerptDocument11 pagesFrom Worry To Worship ExcerptJulie MorrisNo ratings yet

- Quectel GSM FTP at Commands Manual V1.4Document34 pagesQuectel GSM FTP at Commands Manual V1.4Thanh nhaNo ratings yet

- MR NobodyDocument1 pageMR NobodyCatalina PricopeNo ratings yet

- Touchdown PCR PDFDocument6 pagesTouchdown PCR PDFMatheusRsaNo ratings yet

- Varieties and RegistersDocument3 pagesVarieties and RegistersAhron CulanagNo ratings yet

- DSQC 668 Axis Computer: General InformationDocument2 pagesDSQC 668 Axis Computer: General InformationVenkataramanaaNo ratings yet

- World Trade Organisation WTO and Its Objectives and FunctionsDocument7 pagesWorld Trade Organisation WTO and Its Objectives and FunctionsShruti PareekNo ratings yet

- تأثير الغش على أحكام المسؤولية العقديةDocument24 pagesتأثير الغش على أحكام المسؤولية العقديةsirineghozzinefaaNo ratings yet

- The Secret of LaughterDocument5 pagesThe Secret of LaughterlastrindsNo ratings yet