Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis: Dr. Kumail Rizvi, CFA, FRM

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis: Dr. Kumail Rizvi, CFA, FRM

Uploaded by

Wajeeha IqbalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis: Dr. Kumail Rizvi, CFA, FRM

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis: Dr. Kumail Rizvi, CFA, FRM

Uploaded by

Wajeeha IqbalCopyright:

Available Formats

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis

Dr. Kumail Rizvi, CFA, FRM

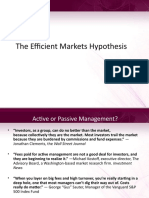

Active or Passive Management?

Investors, as a group, can do no better than the market,

because collectively they are the market. Most investors trail the

market because they are burdened by commissions and fund

expenses. Jonathan Clements, the Wall Street Journal,

June 17, 1997

Fees paid for active management are not a good deal for

investors, and they are beginning to realize it. Michael

Kostoff, executive director, The Advisory Board, a Washingtonbased market research firm. InvestmentNews, February 8, 1999

When you layer on big fees and high turnover, youre really

starting in a deep hole, one that most managers cant dig their

way out of. Costs really do matter. George Gus Sauter,

Manager of the Vanguard S&P 500 Index Fund

Active or Passive Management?

Net (after costs)

Gross (before costs)

Net (after costs)

Gross (before costs)

Net (after costs)

Gross (before costs)

Definition of Efficient Markets

An efficient capital market is a market that is efficient in

processing information.

We are talking about an informationally efficient

market, as opposed to a transactionally efficient

market. In other words, we mean that the market

quickly and correctly adjusts to new information.

In an informationally efficient market, the prices of

securities observed at any time are based on correct

evaluation of all information available at that time.

Therefore, in an efficient market, prices immediately and

fully reflect available information.

Definition of Efficient Markets (cont.)

Professor Eugene Fama, who coined the phrase efficient

markets, defined market efficiency as follows:

"In an efficient market, competition among the many intelligent

participants leads to a situation where, at any point in time,

actual prices of individual securities already reflect the effects

of information based both on events that have already occurred

and on events which, as of now, the market expects to take place

in the future. In other words, in an efficient market at any point

in time the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of

its intrinsic value."

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis

The Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH) is

made up of three progressively stronger forms:

Weak Form

Semi-strong Form

Strong Form

The EMH Graphically

All historical prices and

returns

In this diagram, the circles

represent the amount of

information that each form of

the EMH includes.

Note that the weak form

covers the least amount of

information, and the strong

form covers all information.

Also note that each successive

form includes the previous

ones.

All information, public and

private

Strong Form

Semi-Strong

Weak Form

All public information

The Weak Form

The weak form of the EMH says that past prices, volume, and other

market statistics provide no information that can be used to predict

future prices.

If stock price changes are random, then past prices cannot be used to

forecast future prices.

Price changes should be random because it is information that drives

these changes, and information arrives randomly.

Prices should change very quickly and to the correct level when new

information arrives (see next slide).

This form of the EMH, if correct, repudiates technical analysis.

Most research supports the notion that the markets are weak form

efficient.

The Semi-strong Form

The semi-strong form says that prices fully reflect all

publicly available information and expectations about the

future.

This suggests that prices adjust very rapidly to new

information, and that old information cannot be used to

earn superior returns.

The semi-strong form, if correct, repudiates fundamental

analysis.

Most studies find that the markets are reasonably

efficient in this sense, but the evidence is somewhat

mixed.

The Strong Form

The strong form says that prices fully reflect all

information, whether publicly available or not.

Even the knowledge of material, non-public

information cannot be used to earn superior

results.

Most studies have found that the markets are not

efficient in this sense.

Anomalies

Anomalies are unexplained empirical results that

contradict the EMH:

The Size effect.

The Incredible January Effect.

Day of the Week (Monday Effect).

The Size Effect

Beginning in the early 1980s a number of

studies found that the stocks of small firms

typically outperform (on a risk-adjusted basis)

the stocks of large firms.

This is even true among the large-capitalization

stocks within the S&P 500. The smaller (but still

large) stocks tend to outperform the really large

ones.

The Incredible January Effect

Stock returns appear to be higher in January than

in other months of the year.

This may be related to the size effect since it is

mostly small firms that outperform in January.

It may also be related to end of year tax selling.

The Day of the Week Effect

Based on daily stock prices from 1963 to 1985 Keim

found that returns are higher on Fridays and lower on

Mondays than should be expected.

This is partly due to the fact that Monday returns actually

reflect the entire Friday close to Monday close time

period (weekend plus Monday), rather than just one day.

Moreover, after the stock market crash in 1987, this effect

disappeared completely and Monday became the best

performing day of the week between 1989 and 1998.

Summary of Tests of the EMH

Weak form is supported, so technical analysis cannot

consistently outperform the market.

Semi-strong form is mostly supported , so fundamental

analysis cannot consistently outperform the market.

Strong form is generally not supported. If you have

secret (insider) information, you CAN use it to earn

excess returns on a consistent basis.

Ultimately, most believe that the market is very efficient,

though not perfectly efficient. It is unlikely that any

system of analysis could consistently and significantly

beat the market (adjusted for costs and risk) over the

long run.

You might also like

- MS VIX Futs Opts PrimerDocument33 pagesMS VIX Futs Opts PrimerdmthompsoNo ratings yet

- Basel IV Calculating Ead According To The New Standardizes Approach For Counterparty Credit Risk Sa CCRDocument48 pagesBasel IV Calculating Ead According To The New Standardizes Approach For Counterparty Credit Risk Sa CCRmrinal aditya100% (1)

- EMH Corporate FinanceDocument38 pagesEMH Corporate FinanceIsma NizamNo ratings yet

- The Efficient Markets Hypothesis: Mohammad Ali SaeedDocument21 pagesThe Efficient Markets Hypothesis: Mohammad Ali SaeedBalach MalikNo ratings yet

- IA&M-Module 3 EMHDocument17 pagesIA&M-Module 3 EMHShalini HSNo ratings yet

- (HNS) - IIIyrSem6 - FundamentalsOfInvestments - Week4 - DR - KanuDocument17 pages(HNS) - IIIyrSem6 - FundamentalsOfInvestments - Week4 - DR - Kanumuzamil BhuttaNo ratings yet

- The Efficient Markets HypothesisDocument19 pagesThe Efficient Markets HypothesisAjitNo ratings yet

- Efficient Capital Markets PDFDocument6 pagesEfficient Capital Markets PDFSDPAS100% (1)

- Topic 4A - EMHDocument23 pagesTopic 4A - EMHNoluthando MbathaNo ratings yet

- No. 13 EMHDocument33 pagesNo. 13 EMHayazNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument9 pagesEfficient Market HypothesisPatel Krisha KushangNo ratings yet

- Notes On Efficient Market HypothesisDocument4 pagesNotes On Efficient Market HypothesiskokkokkokokkNo ratings yet

- Individual Work BurseDocument6 pagesIndividual Work BurseMihaelaNo ratings yet

- Efficientmarkethypothesis 111019030158 Phpapp01 PDFDocument10 pagesEfficientmarkethypothesis 111019030158 Phpapp01 PDFDr. H. N. ShivaprasadNo ratings yet

- What Is Market EfficiencyDocument8 pagesWhat Is Market EfficiencyFrankGabiaNo ratings yet

- (Fama, 1970) .: in The Real World of Investment, However, There Are Obvious Arguments Against The EMHDocument4 pages(Fama, 1970) .: in The Real World of Investment, However, There Are Obvious Arguments Against The EMHSamadhi WeeraratneNo ratings yet

- Efficient Markets: A Testable Hypothesis To Answer The Question: How Are Securities Market Prices Determined?Document26 pagesEfficient Markets: A Testable Hypothesis To Answer The Question: How Are Securities Market Prices Determined?james4819No ratings yet

- Market EfficiencyDocument12 pagesMarket Efficiencyhira nazNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 5 Market Efficiency and TradingDocument23 pagesCHAPTER 5 Market Efficiency and TradingLasborn DubeNo ratings yet

- Overview of Financial MarketsDocument15 pagesOverview of Financial MarketsDavidNo ratings yet

- EmtDocument9 pagesEmtcktacsNo ratings yet

- Portfolio & Investment Analysis Efficient-Market HypothesisDocument137 pagesPortfolio & Investment Analysis Efficient-Market HypothesisVicky GoweNo ratings yet

- Fmi Report: Submitted By: SWAPNA (95) MANOJ (94) KANCHAN (100) ANCHIT (101) Lalit Verma (103) VIPINDocument6 pagesFmi Report: Submitted By: SWAPNA (95) MANOJ (94) KANCHAN (100) ANCHIT (101) Lalit Verma (103) VIPINKanchan RaniNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument4 pagesEfficient Market HypothesisRabia KhanNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument3 pagesEfficient Market Hypothesismeetwithsanjay100% (1)

- (Download PDF) Practical Investment Management 4th Edition Strong Solutions Manual Full ChapterDocument30 pages(Download PDF) Practical Investment Management 4th Edition Strong Solutions Manual Full Chapterccoogokr100% (5)

- FIN 2010 Lecture 10: Market Efficiency & Behavioral Finance: Prof. Jangwoo Lee The Chinese University of Hong KongDocument56 pagesFIN 2010 Lecture 10: Market Efficiency & Behavioral Finance: Prof. Jangwoo Lee The Chinese University of Hong KongWai Lam HsuNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument8 pagesEfficient Market HypothesisGaara165100% (1)

- Mppa Efficient Market PortfolioDocument5 pagesMppa Efficient Market PortfoliozaphneathpeneahNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market Hypotheses (Emh) : Random Walk TheoryDocument11 pagesEfficient Market Hypotheses (Emh) : Random Walk Theoryamar2jeetNo ratings yet

- Investment and Portfolio Analysis ": Market Efficiency"Document20 pagesInvestment and Portfolio Analysis ": Market Efficiency"Ahsan IqbalNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market Hypothesis Faisal MeerDocument37 pagesEfficient Market Hypothesis Faisal MeerMuneeza Akhtar Muneeza AkhtarNo ratings yet

- NT 2b Behavioral FinanceDocument7 pagesNT 2b Behavioral FinanceCarmenNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument14 pagesEfficient Market Hypothesissashankpandey9No ratings yet

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument5 pagesEfficient Market HypothesisAdarsh KumarNo ratings yet

- The EMHDocument6 pagesThe EMHMd. Saiful IslamNo ratings yet

- The Capital Markets and Market Efficiency: EightnineDocument9 pagesThe Capital Markets and Market Efficiency: EightnineAnika VarkeyNo ratings yet

- SA&PMDocument102 pagesSA&PMAnkita TripathiNo ratings yet

- Efficient HypothesisDocument19 pagesEfficient HypothesisRawMessNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market Hypothesis: Weak-Form EfficiencyDocument2 pagesEfficient Market Hypothesis: Weak-Form EfficiencyAbdullah ShahNo ratings yet

- Efficent MarketDocument3 pagesEfficent Marketharsh_vineet4No ratings yet

- Market EfficiencyDocument9 pagesMarket Efficiencyiqra sarfarazNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument13 pagesEfficient Market Hypothesiskunalacharya5No ratings yet

- Practical Investment Management 4Th Edition Strong Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument28 pagesPractical Investment Management 4Th Edition Strong Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFAdrianLynchpdci100% (12)

- Testing The Efficiency Market Hypothesis For The Romanian Stock MarketDocument14 pagesTesting The Efficiency Market Hypothesis For The Romanian Stock MarketOana BuseNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market Theory PDFDocument14 pagesEfficient Market Theory PDFJayantNo ratings yet

- Coporate FinanceDocument6 pagesCoporate FinanceMuhammad AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Emh (Efficient Market Hypothesis)Document6 pagesEmh (Efficient Market Hypothesis)Sumit SrivastavNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Efficient Market HypothesisDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Efficient Market Hypothesisc5t0jsyn100% (2)

- Efficient Market HypothsisDocument15 pagesEfficient Market HypothsisAnnas AmanNo ratings yet

- AnswerDocument9 pagesAnswerAnika VarkeyNo ratings yet

- Efficient Market Hypothesis NotesDocument7 pagesEfficient Market Hypothesis NotesAryan AroraNo ratings yet

- Securities Analysis and Portfolio ManagementDocument5 pagesSecurities Analysis and Portfolio ManagementtalhaNo ratings yet

- Historical Background: Louis BachelierDocument6 pagesHistorical Background: Louis BachelierchunchunroyNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Efficient Market HypothesisDocument5 pagesDissertation Efficient Market Hypothesissherryfergusonarlington100% (2)

- Analytical Essay Efficient Market HypothesisDocument6 pagesAnalytical Essay Efficient Market Hypothesistiffanyyounglittlerock100% (2)

- Efficient Market HypothesisDocument7 pagesEfficient Market HypothesisAdedapo AdeluyiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Market Mechanisms and EfficiencyDocument12 pagesChapter 5 Market Mechanisms and EfficiencyBrenden KapoNo ratings yet

- Unit 14 The Efficient Market Hypothesis: DFA1035 Y Fundamentals of Finance and PracticeDocument12 pagesUnit 14 The Efficient Market Hypothesis: DFA1035 Y Fundamentals of Finance and PracticeMîñåk ŞhïïNo ratings yet

- Market EfficiencyDocument14 pagesMarket EfficiencyMrMoney ManNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Management and Investment Analysis:: Market EfficiencyDocument9 pagesPortfolio Management and Investment Analysis:: Market EfficiencyTanvirFaisal420No ratings yet

- Technical AnalysisDocument43 pagesTechnical Analysissarakhan0622No ratings yet

- Zara Case IiDocument2 pagesZara Case IiElisa PauluzziNo ratings yet

- Intro To Financial RatiosDocument2 pagesIntro To Financial Ratiosmuhammadtaimoorkhan100% (3)

- Collocations in BusinessDocument2 pagesCollocations in BusinessBoddisatva Lofthouse-ArmatradingNo ratings yet

- Emad A. Zikry - Implications of Recent Money Market Fund Reform PassageDocument2 pagesEmad A. Zikry - Implications of Recent Money Market Fund Reform PassageEmad-A-ZikryNo ratings yet

- Alternative InvestmentsDocument63 pagesAlternative InvestmentsAspanwz SpanwzNo ratings yet

- ITC Coffee 4th Report 20210930 Web PagesDocument332 pagesITC Coffee 4th Report 20210930 Web PagesAlejandro MotorToolsNo ratings yet

- Merger &acquisitionDocument150 pagesMerger &acquisitionMadhvendra BhardwajNo ratings yet

- ML COPA IntegrationDocument18 pagesML COPA IntegrationSamik BiswasNo ratings yet

- Contract Farming in IndiaDocument39 pagesContract Farming in IndiaaksjsimrNo ratings yet

- Chapter 01Document30 pagesChapter 01diana sabrinaNo ratings yet

- Womens Intercultural PerformanceDocument238 pagesWomens Intercultural PerformanceYusufNo ratings yet

- Treasury BillsDocument11 pagesTreasury Billsjigna kelaNo ratings yet

- Case in PointDocument4 pagesCase in PointEshaan SharmaNo ratings yet

- RG GASPE Chapter 45 Financial InstrumentsDocument139 pagesRG GASPE Chapter 45 Financial InstrumentsTom ChanNo ratings yet

- Concepts and Perspectives in Human Resource ManagementDocument12 pagesConcepts and Perspectives in Human Resource Management29_ramesh170No ratings yet

- AJAY E Commerce Project PDFDocument55 pagesAJAY E Commerce Project PDFSagar Baranwal29% (7)

- Project SynopsisDocument8 pagesProject SynopsisMalini M RNo ratings yet

- 3.finance Capitalism Versus Industrial Capitalism3Document17 pages3.finance Capitalism Versus Industrial Capitalism3PrevalisNo ratings yet

- Inventory Management: Rajendran Ananda KrishnanDocument14 pagesInventory Management: Rajendran Ananda KrishnanShishir GyawaliNo ratings yet

- Google FormsDocument5 pagesGoogle Formsmanoj kumar DasNo ratings yet

- Collapse of Barings BankDocument19 pagesCollapse of Barings BankPratik ShahNo ratings yet

- Market Breadth BrochureDocument10 pagesMarket Breadth BrochureStevenTsaiNo ratings yet

- Money Banking and The Financial System 2nd Edition Hubbard OBrien Test BankDocument32 pagesMoney Banking and The Financial System 2nd Edition Hubbard OBrien Test Banktina100% (29)

- Ms 06 Imp Short Important Question GistDocument72 pagesMs 06 Imp Short Important Question Gistrone9898No ratings yet

- Group Project Guidelines - 2022Document4 pagesGroup Project Guidelines - 2022azridaNo ratings yet

- How Sensory Marketing Affects Consumer Buying BehaviorDocument6 pagesHow Sensory Marketing Affects Consumer Buying BehaviorAmber JillaniNo ratings yet

- Junk Car Removal ContentDocument3 pagesJunk Car Removal ContentSama ZaidiNo ratings yet