Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Using The Stanislavski Method To Create A Performance

Using The Stanislavski Method To Create A Performance

Uploaded by

Gabriel Castillo0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views32 pagesActing method

Original Title

Using the Stanislavski Method to Create a Performance

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentActing method

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as ppt, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views32 pagesUsing The Stanislavski Method To Create A Performance

Using The Stanislavski Method To Create A Performance

Uploaded by

Gabriel CastilloActing method

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as ppt, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 32

Always start from an understanding of the text.

Look for the facts of what happens, what the

characters do, and how the plot unfolds.

This includes the backstory—what happens

before the play starts.

Look at the play’s given circumstances.

Identify the play’s setting and research it.

Familiarize yourself with the history,

manners, culture, fashion, style of

movement, mind-set, and behavior of the

world of the play.

The External Plane: the events, the facts

The Social Plane: the historical and cultural

context

The Literary Plane: the playwright’s voice,

style, rhetoric, and structure.

The Aesthetic Plane: the production

elements, such as costumes and scenery.

The Internal Plane: the characters’ inner lives

and psychology

The Physical Plane: the “plastic” of the

character, meaning the way the character

looks, moves, and talks.

Focus on the heart of the play—its

themes, the main character’s struggle on

an emotional and psychological level, the

protagonist’s hamartia (core wound, tragic

flaw, etc.), what is at stake.

Re-read and consider the play from

your character’s perspective.

What is your character’s journey

through the story of the play? What

does he/she want? What are his/her

obstacles? What tactics does he/she

employ?

What to Look For and How to Approach the Role

What does your character want from each

of the other characters?

How does your character feel about each

of them?

How well does your character understand

the other characters?

How well does your character understand

his- or herself?

How does your character relate to other

people?

Each character in a play has a superobjective—the

ultimate dramatic need that guides his/her journey

over the course of the whole play.

The superobjective can be broken down into smaller,

more manageable, easily studied units. Each unit

consists of a major step towards the achievement of

that superobjective.

Keep the “big picture” in mind as you divide the script

into units, making sure each unit contributes to the

overall throughline (the logical progression of events

leading the protagonist towards his/her intended

superobjective—whether or not it is achieved).

Be aware of the counter-throughline (the logically

progressing efforts of the antagonist OR the logical

progression of the obstacles).

Further divide each unit into beats—a character’s

use of one tactic in his/her attempt at achieve the

goal of the unit. Units often have many beats.

A character will use one tactic to achieve the

objective of the unit or a step therein. Based on

its perceived success or failure, he/she will adapt

the tactic to the new circumstances.

Score your script: In preparation for playing the

role, place brackets around each beat in which

your character participates. For each beat, write

out the (I) Intension, (O) Objective, and (N) Name.

Discuss your beatwork with your director and/or

scene partner, to insure that you are all in

agreement about the action of the scene.

Who is the leader in the scene?

Who is the follower? Which is your

character?

Note: A character may lead in one

beat/unit/scene and follow in another.

What do you do at each change of beat?

What new action do you take?

While you may be able to analyze the text

to observe your character’s shift in tactics,

much of this is best discovered while

working with the other actors in the scene.

Exploring the Physical Life of the Character

Consider how the Given Circumstances of both

the play and the character effect the physicality

of your characterization.

The Play: time period, setting, time of day,

weather, historical context, cultural context, etc.

The Character: social class, family dynamics,

social dynamics, education, wealth, manners,

philosophy, religiosity, relationships, personal

history, gender, race, sexuality, personality,

present emotional state, etc.

Use this information to guide you in establishing

how the character moves, speaks and

physically interacts with others and his or her

environment.

Stanislavski often said it was by means of the

word, of language, that the character’s objective

would be fulfilled.

You must give the lines shadings, nuances, mood,

coloration, emotional reality, and energy, all of

which should ideally arise organically—not

mechanically—by means of precisely setting up the

framework in your mind. Do this by finding the

right moment-to-moment “if.”

Use your training in speech and dialect to find the

voice of the character. Find the cadence and

timbre of the character’s voice through your

observation of the world around you.

Part of your job is to embody the physical

life of the character, including his/her

posture, gait, use of gesture, expression,

eye contact, and general movement styles.

Again, this is something that is embodied

organically without seeming preconceived

or calculated by means of finding the right

“if.”

It is important for you to be observant of the

repertoire of movements in the people

around you. Also, look for the animal-like

movements exhibited by those around you.

Stanislavski’s Method suggests extensive work on the

inner life of the character, maintaining that the actor’s

use of body and voice will then emerge out of the that

unified, clear vision of the character’s inner life.

As the practice of Stanislavski’s Method developed,

later practitioners found that working from the inside

out was too cerebral, and they began exploring

working from the outside in to create more physically

interesting performances. The effect, however,

seemed to lead to less unified and thoughtful work.

At present, most Method practitioners suggest

working simultaneously from the inside out and the

outside in—in order to create performances that are

both mindful and physical

A paradox is the truthful co-existence of

two polar opposites.

Actors often find great freedom to riff

within the confines of very rigid and

specific parameters of characterization

and action.

It is not unlike how musicians can “jam” or

create solos out of a strict, repetitive chord

progression.

Breathing Life Into the Text

Before you enter, you should know where

you have just been, what were the conditions

of this previous space, what you have just

been doing, why are you coming into this

new space, what is this new space, and what

do you immediately want as you enter?

Explore the moment of orientation—that is,

the moment in which you orient yourself to

where you are and, if applicable, to the other

character(s) in that new space.

How does your entrance alter the particles in

the space?

As you design the blocking, let it emerge

organically as part of the objectives of the

characters. Blocking should be

purposeful—not decorative or separate

from the intentions of the characters.

As much as you can, design blocking so

that it adheres to the principles of stage

presence and blocking that you have

studied; however, your first responsibility

is truth of characters in the moment.

Is there any stage business that could be

incorporated into the scene?

Stage Business can help give the actor an way to

enter into the reality of the scene. Using the

principle of Spheres of Concentration, you can

first find the reality of stirring a pot, going through

a stack of mail, setting the table, and then expand

outward to the larger, more challenging realities of

the scene.

Stage Business should be relevant to the overall

action of the scene, help to establish setting and

mood, reveal character, and if possible, make a

symbolic contribution to the meaning of the scene.

Stanislavski noted the existence of

contradictory positive and negative character

traits, desires, and impulses.

Look for opportunities for villains to be

charming and heroes to be wicked, etc.

Likewise, behavior and speech is often the

opposite of one’s emotions or intentions.

Characters often suppress emotions that

threaten to expose them. Have you ever told

someone to call you, hoping that you will

never hear from them again?

Begin to memorize the words and

blocking in concert, as they are

inseparable.

This should be the halfway mark in your

rehearsal process. As is often

misperceived by the novice,

memorization is not the final product of

the rehearsal process.

Polishing the Mechanics and Finding the Deeper Life of the Character

Use relaxation and concentration exercises

to prepare for all rehearsal and

performance work. Remove tension and

sharpen your focus to welcome in order to

welcome the life of the character into your

body.

Use sense memory and affective memory

efforts to recreate and fully inhabit the

reality of each beat of the text.

Take into account what happens to the

characters before the play begins—the

backstory.

Take into account what happens in the

time between the scenes when the

character is offstage—the between-time.

Take into account what happens to your

character after the scene ends. Are you

setting up the character for where he/she

is headed?

Consider how the accumulative affect of

the action might alter both the inner life

and the physicality of the character.

What does your character want in each of

the relationships with the characters in

each beat?

Does the character succeed in getting

what he or she wants from the other

character(s) in each beat?

What does the character do when he/she

does or does not attain an objective?

Through all of the work up until now,

you may be starting to get a clearer

glimpse of the character’s underlying,

subtextual unconscious motivations

and ambivalences, which will add

depth to your characterization as

they gradually dawn on you and

emerge because of your work on the

script.

Look back through your beatwork and

refine/adjust it based on your discoveries.

Allow yourself to “forget” what you have

chosen (because it has been assimilated

and absorbed into the preconscious area

of the unconscious) as you act organically

when you actually perform the rehearsed

piece, at which point all the work on the

role is pushed away from conscious

awareness and acting it—performing it—

takes over.

By this time, too, you will have found

the correct rhythm and tempo for

each line, beat, unit, scene, act, and

the play as a whole.

As you begin to perform the piece for

audiences, continue to discover new

things and refine your work.

You might also like

- Seven Pillars Acting: A Comprehensive Technique for the Modern ActorFrom EverandSeven Pillars Acting: A Comprehensive Technique for the Modern ActorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Etextbook 978 0132729833 Managing Behavior in OrganizationsDocument61 pagesEtextbook 978 0132729833 Managing Behavior in Organizationsbeatrice.bump83798% (51)

- Meisner in Practice: A Guide for Actors, Directors and TeachersFrom EverandMeisner in Practice: A Guide for Actors, Directors and TeachersNo ratings yet

- Eric Morris No Acting Please PDFDocument2 pagesEric Morris No Acting Please PDFRick0% (6)

- Freeing the Actor: An Actor's Desk Reference. Over 140 Exercises and Techniques to Free the ActorFrom EverandFreeing the Actor: An Actor's Desk Reference. Over 140 Exercises and Techniques to Free the ActorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Michael Shurtleff - AuditionDocument5 pagesMichael Shurtleff - AuditionȘtefan Mura0% (2)

- Uta HagenDocument35 pagesUta HagenLarissa Saraiva67% (9)

- Knowing The Body: Malmgren ActingDocument315 pagesKnowing The Body: Malmgren ActingJordanCampbell100% (3)

- Acting For The CameraDocument13 pagesActing For The CameraRavikanth Perepu0% (1)

- The Warner Loughlin Technique: An Acting RevolutionFrom EverandThe Warner Loughlin Technique: An Acting RevolutionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- CHEKOV TehniqueDocument41 pagesCHEKOV TehniqueYudhi Faisal86% (7)

- The Knowing Body - On Laban Yat Acting TechniqueDocument22 pagesThe Knowing Body - On Laban Yat Acting TechniquelironnnNo ratings yet

- Method Acting ExercisesDocument5 pagesMethod Acting ExercisesSaran Karunan100% (1)

- KEY TO THE RUBRICS OF MIND - AgrawalDocument169 pagesKEY TO THE RUBRICS OF MIND - Agrawalalex100% (5)

- Essay (Family Problems)Document2 pagesEssay (Family Problems)Crystal ApinesNo ratings yet

- Actor's Alchemy: Finding the Gold in the ScriptFrom EverandActor's Alchemy: Finding the Gold in the ScriptRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Meisner PDFDocument246 pagesMeisner PDFasslii_83100% (1)

- ChekhovDocument16 pagesChekhovKevin Jung100% (1)

- Character and Role Analysis ResourcesDocument9 pagesCharacter and Role Analysis ResourcesBen Donald100% (2)

- Laban Advanced Characterization PDFDocument8 pagesLaban Advanced Characterization PDFKatie Norwood AlleyNo ratings yet

- Play Analysis WorksheetDocument2 pagesPlay Analysis Worksheetdramaqueen224689235100% (2)

- Method Acting Lecture NotesDocument23 pagesMethod Acting Lecture NotesNick Driscoll100% (6)

- Teaching StanislavskiDocument108 pagesTeaching StanislavskiResearch Office100% (12)

- Lee Strasberg S MethodDocument7 pagesLee Strasberg S Methodnervousystem100% (1)

- ACTING General HandoutDocument4 pagesACTING General HandoutNagarajuNoolaNo ratings yet

- Uta Hagen Lesson PlanDocument13 pagesUta Hagen Lesson Planapi-283596499100% (2)

- Overcoming Self-Defeating Behaviors: The Outer-ChildDocument22 pagesOvercoming Self-Defeating Behaviors: The Outer-ChildKristin Taylor Petrucci100% (3)

- The Violet Flame For Financial ProsperityDocument5 pagesThe Violet Flame For Financial Prosperitysshyamkant4529100% (19)

- Principles of ActingDocument4 pagesPrinciples of ActingabconleyNo ratings yet

- Stanislavski TechniquesDocument2 pagesStanislavski Techniquesapi-509765058No ratings yet

- 40 Questions of One Role: A method for the actor's self-preparationFrom Everand40 Questions of One Role: A method for the actor's self-preparationNo ratings yet

- Director Actor Coach: Solutions for Director/Actor ChallengesFrom EverandDirector Actor Coach: Solutions for Director/Actor ChallengesNo ratings yet

- Breaking Down Your Script: The Compact Guide: A Step-by-Step Guide for the ActorFrom EverandBreaking Down Your Script: The Compact Guide: A Step-by-Step Guide for the ActorNo ratings yet

- Acting Classes - Meyerhold & BrechtDocument12 pagesActing Classes - Meyerhold & BrechtcotiprNo ratings yet

- Acting TheoryDocument7 pagesActing TheoryAlan Santoyo LapinelNo ratings yet

- The Actor in YouDocument9 pagesThe Actor in YouIonut IvanovNo ratings yet

- Michael Chekhov and His Approach To Acting in Contemporary PerforDocument42 pagesMichael Chekhov and His Approach To Acting in Contemporary PerforAmbaejo96100% (1)

- Stanislavski ExercisesDocument9 pagesStanislavski Exercisespsychonomy100% (14)

- Basics of The Meisner TechniqueDocument3 pagesBasics of The Meisner TechniqueMrToad100% (1)

- ActingDocument29 pagesActingTaylor RigginsNo ratings yet

- Acting NotesDocument3 pagesActing Notesapi-676894540% (1)

- Stanislavski PDFDocument26 pagesStanislavski PDFFRANCISCO CARRIZALES VERDUGONo ratings yet

- Lee StrasbergDocument21 pagesLee StrasbergAnonymous 96cBoB3100% (7)

- Method ActingDocument8 pagesMethod ActingRolly Zsigmond100% (3)

- What Is ActingDocument26 pagesWhat Is Actingadinfinitya100% (2)

- Stanislavski NotesDocument9 pagesStanislavski Notesapi-250740140No ratings yet

- Method Acting - WikipediDocument6 pagesMethod Acting - WikipedichrisdelegNo ratings yet

- Coaching Actors PDFDocument8 pagesCoaching Actors PDFAntonio Vettraino100% (1)

- Learning How To Act: A Jigsaw ExerciseDocument5 pagesLearning How To Act: A Jigsaw ExerciseSanjay Thapa50% (6)

- Sanford MeisnerDocument25 pagesSanford MeisnerBrad Isaacs100% (8)

- Method Acting TechniquesDocument18 pagesMethod Acting Techniquessenvasn100% (4)

- Differences Between Stage Acting and Film ActingDocument6 pagesDifferences Between Stage Acting and Film ActingTanya choudharyNo ratings yet

- The Art of Directing Actors 25 PagesDocument25 pagesThe Art of Directing Actors 25 PagesErnest Goodman100% (2)

- Michael Chekhov - On The Technique of Acting-Harper Perennial (1991) (Z-Lib - Io)Document239 pagesMichael Chekhov - On The Technique of Acting-Harper Perennial (1991) (Z-Lib - Io)robert royNo ratings yet

- Tips For Student ActorsDocument2 pagesTips For Student ActorsKatie Norwood AlleyNo ratings yet

- MonologuesDocument11 pagesMonologuesNuman KhanNo ratings yet

- OutDocument287 pagesOutsalica4gbNo ratings yet

- Spatial Perception Ability From Two-Dimensional Media: Facta UniversitatisDocument10 pagesSpatial Perception Ability From Two-Dimensional Media: Facta Universitatissalica4gbNo ratings yet

- Fascist Aesthetics in Hollywood CinemaDocument19 pagesFascist Aesthetics in Hollywood Cinemasalica4gbNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Success Spatial Ability - Practice Test 1 PDFDocument12 pagesPsychometric Success Spatial Ability - Practice Test 1 PDFsalica4gbNo ratings yet

- HunaDocument38 pagesHunaDilip Gaikwad50% (2)

- JRNL - Self-Esteem Dengan Nomophobia UI BandungDocument5 pagesJRNL - Self-Esteem Dengan Nomophobia UI BandungLeo GalileoNo ratings yet

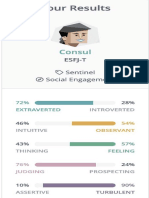

- ESFJ Career+StrengthsDocument120 pagesESFJ Career+StrengthsAlexandru PopaNo ratings yet

- Innovation TrissaDocument14 pagesInnovation TrissaMay Ann VelosoNo ratings yet

- psychopathology:-: Unit 1Document22 pagespsychopathology:-: Unit 1BlackSpider SpiderNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Clinical Decision Making: Megan Smith, Joy Higgs and Elizabeth EllisDocument12 pagesFactors Influencing Clinical Decision Making: Megan Smith, Joy Higgs and Elizabeth EllisSyerin AudiaNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY LOSS and GRIEVINGDocument3 pagesCASE STUDY LOSS and GRIEVINGISMAL ISMAILNo ratings yet

- Abdul Hadi 105368Document4 pagesAbdul Hadi 105368zayan mustafaNo ratings yet

- AEQ Manual 2005Document54 pagesAEQ Manual 2005Vicențiu Ioan100% (1)

- What'S Your Learning Style?: Learning Styles Self-AssessmentDocument12 pagesWhat'S Your Learning Style?: Learning Styles Self-AssessmentJj Cor-BanoNo ratings yet

- Foundation of Human Relations & Human Behavior inDocument22 pagesFoundation of Human Relations & Human Behavior injennyneNo ratings yet

- Table 5-8 - DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria For Panic DisorderDocument1 pageTable 5-8 - DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria For Panic DisorderDragutin PetrićNo ratings yet

- HUMOUR AND LAUGHTER THERAPY KmitaDocument10 pagesHUMOUR AND LAUGHTER THERAPY Kmitayanti ikmNo ratings yet

- Loss and GriefDocument14 pagesLoss and Griefnursereview100% (3)

- Grief and Loss of A Caregiver in ChildrenDocument5 pagesGrief and Loss of A Caregiver in ChildrenGanda KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Anxiety PracticalDocument6 pagesAnxiety PracticalJyoti ChhabraNo ratings yet

- The Importance, Meaning, and Assumptions of ArtDocument8 pagesThe Importance, Meaning, and Assumptions of ArtChaddlyn Rose SamaniegoNo ratings yet

- Gimble Guide To The FeywildDocument84 pagesGimble Guide To The FeywildYasha515100% (3)

- Definition of A Stress: Crisis Management WorkshopDocument22 pagesDefinition of A Stress: Crisis Management WorkshopTubocurareNo ratings yet

- Developmental Milestones 3:: Social-Emotional DevelopmentDocument6 pagesDevelopmental Milestones 3:: Social-Emotional DevelopmentHOA TRƯƠNGNo ratings yet

- Here Are 25 Ways You Can Control Your Anger: Count DownDocument3 pagesHere Are 25 Ways You Can Control Your Anger: Count DownKevin EspirituNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument271 pagesUntitledShreya ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- PSYCHOLOGY Paper 1 PDFDocument36 pagesPSYCHOLOGY Paper 1 PDFmostafa barakatNo ratings yet

- Yoga Therapy IntroDocument2 pagesYoga Therapy IntrorajuchinaNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTDDocument20 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTDJoy PascoNo ratings yet