Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism

Uploaded by

jessabhel bosito0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

271 views20 pages1. Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that argues actions should be judged based on their consequences, specifically whether they maximize happiness and pleasure for the greatest number of people.

2. Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill were two influential utilitarian philosophers. Bentham argued for a quantitative approach focused on pleasure and pain, while Mill argued higher intellectual pleasures were more important than basic physical pleasures.

3. Utilitarianism balances individual rights and justice with achieving the greatest good for the greatest number. While it can justify violating individual rights in some cases, it also supports the idea of moral and legal rights that should not be infringed

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document1. Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that argues actions should be judged based on their consequences, specifically whether they maximize happiness and pleasure for the greatest number of people.

2. Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill were two influential utilitarian philosophers. Bentham argued for a quantitative approach focused on pleasure and pain, while Mill argued higher intellectual pleasures were more important than basic physical pleasures.

3. Utilitarianism balances individual rights and justice with achieving the greatest good for the greatest number. While it can justify violating individual rights in some cases, it also supports the idea of moral and legal rights that should not be infringed

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

271 views20 pagesUtilitarianism

Utilitarianism

Uploaded by

jessabhel bosito1. Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that argues actions should be judged based on their consequences, specifically whether they maximize happiness and pleasure for the greatest number of people.

2. Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill were two influential utilitarian philosophers. Bentham argued for a quantitative approach focused on pleasure and pain, while Mill argued higher intellectual pleasures were more important than basic physical pleasures.

3. Utilitarianism balances individual rights and justice with achieving the greatest good for the greatest number. While it can justify violating individual rights in some cases, it also supports the idea of moral and legal rights that should not be infringed

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 20

UTILITARIANISM

Chapter Content

• The Principle of Utility

• Principle of the Greatest Number

• Justice and Moral Rights

Objectives

1. Discuss the basic principles of utilitarian ethics;

2. Distinguish between two utilitarian models: the quantitative model of

Jeremy Bentham and the qualitative model of John Stuart Mill; and

3. Apply utilitarianism in understanding and evaluating local and

international scenarios.

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832)

on the Principle of Utility

• the principle of utility is about our subjection to two sovereign

masters: pleasure and pain.

• refers to the motivation of our actions as guided by our avoidance

of pain and our desire for pleasure.

• refers to pleasure as good if, and only if, they produce more

happiness than unhappiness.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)

on the Happiness Principle

• He reiterates moral good as happiness and, consequently,

happiness as pleasure.

• What makes people happy is intended pleasure and what makes us

unhappy is the privation of pleasure.

• Things that produce happiness and pleasure are good; whereas,

those that produce unhappiness and pain are bad.

• For Bentham and Mill, the pursuit for pleasure and the avoidance of

pain are not only important principles— they are in fact the only

principle in assessing an action’s morality, e.g., Why is it preferable to

eliminate criminality (or criminals)?

Felicific Calculus

• a common currency framework that calculates the pleasure that

some actions can produce.

Felicific Calculus

• Intensity: How strong is the pleasure?

• Duration: How long will the pleasure last?

• Certainty or Uncertainty: How likely or unlikely is it that the pleasure will occur?

• Propinquity or remoteness: How soon will the pleasure occur?

• Fecundity: The probability that the action will be followed by sensations of the

same kind.

• Purity: The probability that it will not be followed by sensations of the opposite

kind.

• Extent: How many people will be affected?

• Contrary to Bentham, Mill argues that quality is more preferable

than quantity.

• An excessive quantity of what is otherwise pleasurable might

result in pain. Whereas eating the right amount of food can be

pleasurable, excessive eating may not be.

• For Mill, there are higher intellectual and lower base desires.

• We as moral agents, are capable of searching and desiring higher

intellectual pleasures more than animals.

• We undermine ourselves if we only and primarily desire sensuality

because we are capable of higher intellectual pleasurable goods.

• In deciding over two comparable pleasures, it is important to

experience and to discover which one is actually more preferred than

the other.

• What Mill discovers anthropologically is that actual choices of

knowledgeable persons point that higher intellectual pleasures are

preferable than purely sensual appetites.

The Principle of the Greatest Number

• Utilitarianism is not only about our individual pleasures, regardless of

how high, intellectual, or in other ways noble it is, but it is also about

the pleasure of the greatest number affected by the consequences of

our actions.

• Utilitarianism is not dismissive of sacrifices that procure more

happiness for others.

• Utilitarianism is not at all separate from liberal social practices that

aim to improve the quality of life for all persons.

Justice and Moral Rights

• Mill understands justice as a respect for rights directed toward

society’s pursuit of the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

• For him, rights are a valid claim on society and are justified by

utility.

• Utilitarians argue that issues of justice carry a very strong

emotional import because the category of rights is directly

associated with the individual’s most vital interests. All of these

rights are predicated on the person’s right to life. Mill describes:

To have a right, then is, I conceive, to have something which society ought to defend me in

the possession of. If the objector goes on to ask why it ought, I can give him no other reason

than general utility. If that expression does not seem to convey a sufficient feeling of the

strength of the obligation, nor to account for the peculiar energy of the feeling, it is because

there goes to the composition of the sentiment, not a rational only but also an animal element,

the thirst for retaliation; and this thirst derives its intensity, as well as its moral justification,

from the extraordinarily important and impressive kind of utility which is concerned. The

interest involved is that of security, to everyone’s feelings the most vital of all interests.

• Mill creates a distinction between legal rights and their

justification. He points out that when legal rights are not morally

justified in accordance to the greatest happiness principle, then

these rights need neither be observed, nor be respected. This is

like saying that there are instances when the law is not morally

justified and, in this case, even objectionable.

• While it can be justified why others violate legal rights, it is an act

of injustice to violate an individual’s moral rights. Going back to

the case of wiretapping, it seems that one’s right to privacy can be

sacrificed for the sake of the common good. This means that

moral rights are only justifiable by considerations of greater

overall happiness.

• In this sense, the Principle of Utility can theoretically obligate us

to steal, kill, and the like.

• There is runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks.

• Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to

move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing

some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this

lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However

you notice that there is one person on the side track.

• You have two options:

• Do nothing, and the trolley kills the five people on the main track.

• Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will

kill one person.

• Which is the moral choice?

Let us complicate an already complicated moral

dilemma:

• A. what if the one person on the side track is your loved one?

• B. What if the 5 people are hardened criminals each guilty of a

heinous crime?

• C. What if the solitary person is a toddler while the 5 people are

all elderly and individually sick?

You might also like

- Research ProposalDocument6 pagesResearch Proposalapi-355503275No ratings yet

- Science, Technology, & SocietyDocument11 pagesScience, Technology, & SocietyChad BroskiNo ratings yet

- Chapter II - Utilitarianism: Foundations of Moral ValuationDocument26 pagesChapter II - Utilitarianism: Foundations of Moral ValuationAngelene MangubatNo ratings yet

- Staffing in International ContextDocument22 pagesStaffing in International Contextrichagoel.2725130% (1)

- Lacson vs. Perez DigestDocument2 pagesLacson vs. Perez DigestNiq Polido80% (5)

- Bounce Back BIG by Sonia Ricotti (2020) PDFDocument36 pagesBounce Back BIG by Sonia Ricotti (2020) PDFMaxbell BogarinNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 2 - UTILITARIANISM - LECTURE AutosavedDocument71 pagesCHAPTER 2 - UTILITARIANISM - LECTURE AutosavedLorie Jean VenturaNo ratings yet

- Sts Report Group5 1Document28 pagesSts Report Group5 1Dorothy RomagosNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 StudentDocument38 pagesLesson 3 StudentZane James SebastianNo ratings yet

- ART Unit 1 (REVIEWER PRELIM)Document5 pagesART Unit 1 (REVIEWER PRELIM)Aleah Jasmin PaderezNo ratings yet

- Research in Child Adolescent and DevelopmentDocument41 pagesResearch in Child Adolescent and DevelopmentNT MOVIES100% (1)

- Government of The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesGovernment of The PhilippinesBryll NoveleroNo ratings yet

- Surigao Del Sur State University: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesSurigao Del Sur State University: Republic of The PhilippinesRicarte FernandezNo ratings yet

- ExerciseDocument3 pagesExerciseRudelyn Andres BarcelonaNo ratings yet

- NSTP Topical PresentationsDocument60 pagesNSTP Topical PresentationsMary Joyce Alcazar Ricalde100% (2)

- Lesson 2Document19 pagesLesson 2Raymon Villapando Bardinas100% (1)

- Political SelfDocument8 pagesPolitical SelfFRANC MELAN TANAY LANDONGNo ratings yet

- History and HistoriographyDocument20 pagesHistory and HistoriographyRye FelimonNo ratings yet

- Icon, Index, Symptom, Signal and SymbolDocument13 pagesIcon, Index, Symptom, Signal and SymbolBea RoqueNo ratings yet

- 4as Lesson PlanDocument6 pages4as Lesson Planblack moonNo ratings yet

- The Nature of MathematicsDocument34 pagesThe Nature of MathematicsGabriele Yadsendew TuazonNo ratings yet

- The Preamble: (Philippine 1987 Constitution)Document40 pagesThe Preamble: (Philippine 1987 Constitution)kristine319No ratings yet

- Ge 1 New Long Bond PaperDocument22 pagesGe 1 New Long Bond PaperJuliet Marie Mijares0% (1)

- Nocebo JeaneDocument10 pagesNocebo Jeanejeanemariemadrazo50No ratings yet

- Edueng04 SLBPDocument32 pagesEdueng04 SLBPJiro Hendrix AlbertNo ratings yet

- The Writing History During The Spanish PeriodDocument14 pagesThe Writing History During The Spanish Periodkean redNo ratings yet

- Development of Science in MesoamericaDocument2 pagesDevelopment of Science in MesoamericaChristine Payopay0% (1)

- Module 5Document6 pagesModule 5Francisco Christia Kay R.100% (1)

- Understanding The Self B.SociologyDocument7 pagesUnderstanding The Self B.SociologyMacky BulawanNo ratings yet

- Reflection Papers 7Document12 pagesReflection Papers 7Shiela Marie NazaretNo ratings yet

- Self 2020 Social, Environmental, and Other Life FactorsDocument4 pagesSelf 2020 Social, Environmental, and Other Life Factorsbully boyNo ratings yet

- An Anthropological AND Psychological ViewsDocument41 pagesAn Anthropological AND Psychological ViewsNozid Arerbac YahdyahdNo ratings yet

- Building and Enhancing New Literacies Across The Curriculum - Globalization & Cultural & Multicultural Literacies Lecture 1Document4 pagesBuilding and Enhancing New Literacies Across The Curriculum - Globalization & Cultural & Multicultural Literacies Lecture 1Jenny Rose GonzalesNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Evolution of The Philippine ConstitutionDocument5 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Evolution of The Philippine ConstitutionGuki SuzukiNo ratings yet

- Tcsol - C3-C6Document28 pagesTcsol - C3-C6abegail libuitNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet 2 - Mumbaki Film Analysis: Activity 2 GE Elec 2 - Philippine Indigenous CommunitiesDocument1 pageActivity Sheet 2 - Mumbaki Film Analysis: Activity 2 GE Elec 2 - Philippine Indigenous Communitiesluisa radaNo ratings yet

- 20th CenturyDocument42 pages20th Centuryjordaliza buyagaoNo ratings yet

- NSTP 2.3.2-Information Sheet TeamBuildingDocument2 pagesNSTP 2.3.2-Information Sheet TeamBuildingVeraniceNo ratings yet

- Material and Spiritual SelfDocument45 pagesMaterial and Spiritual SelfDanao Patricia AnneNo ratings yet

- HUM 113 - 1 Art History, Art Appreciation, Art, Creativity, Imagination, and The ExpressionDocument8 pagesHUM 113 - 1 Art History, Art Appreciation, Art, Creativity, Imagination, and The ExpressionShiela ZanneNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document13 pagesPresentation 1Kenneth PurcaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Alfredo v. LagmayDocument5 pagesDr. Alfredo v. Lagmaymelvin dipasupilNo ratings yet

- Philippine Political CaricatureDocument16 pagesPhilippine Political CaricatureGianne Karl AlmarinesNo ratings yet

- What Does It Mean To Be A FilipinoDocument2 pagesWhat Does It Mean To Be A FilipinoHyacinth Jhay F. Jabiniao100% (1)

- Reaction PaperDocument3 pagesReaction PaperShean KevinNo ratings yet

- Why The World Needs WikiLeaksDocument5 pagesWhy The World Needs WikiLeaksleana marie ballesterosNo ratings yet

- APPLICATION AND-WPS OfficeDocument2 pagesAPPLICATION AND-WPS OfficeJonathia Willian AngcaoNo ratings yet

- ED 105 Facilitating Learning Module 5 6Document19 pagesED 105 Facilitating Learning Module 5 6Jodelyn Quirao AlmarioNo ratings yet

- GEC112 - Readings in Philippine History Chapter 1Document15 pagesGEC112 - Readings in Philippine History Chapter 1Johara BayabaoNo ratings yet

- 1 Feminism in Popular Culture Module 4a.pptx - 2Document11 pages1 Feminism in Popular Culture Module 4a.pptx - 2Jesa TanNo ratings yet

- Characteristics and Conventions in The Mathematical LanguangeDocument18 pagesCharacteristics and Conventions in The Mathematical LanguangeKeizsha LNo ratings yet

- Malalis, Ronnie O. Ped 3 October 3, 2020 Group 2 Reflection On Every Kid Needs A ChampionDocument1 pageMalalis, Ronnie O. Ped 3 October 3, 2020 Group 2 Reflection On Every Kid Needs A ChampionRonnie Oliva MalalisNo ratings yet

- M9-A Political SelfDocument41 pagesM9-A Political SelfEsther Joy HugoNo ratings yet

- MRR6Document1 pageMRR6Dexter CorpuzNo ratings yet

- ACTIVITY 3 - NSTP1 - Answered VersionDocument4 pagesACTIVITY 3 - NSTP1 - Answered VersionLamour ManlapazNo ratings yet

- RIZALDocument3 pagesRIZALPaula Kathlen GeraldezNo ratings yet

- Is Globalization More of A Curse Than A BlessingDocument3 pagesIs Globalization More of A Curse Than A BlessingAthena JonesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Nature of Globalization (My Book)Document36 pagesChapter 1 Nature of Globalization (My Book)Arnel Jay FloresNo ratings yet

- TH Self, Society and CultureDocument14 pagesTH Self, Society and Culturerosana f.rodriguez100% (1)

- 16 Philippine-American WarDocument24 pages16 Philippine-American Warhyunsuk fhebieNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Badminton from 1870 to 1949From EverandA Brief History of Badminton from 1870 to 1949Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Ethics 2 2Document18 pagesEthics 2 2Renante CabalNo ratings yet

- 15 UtilitarianismDocument25 pages15 UtilitarianismGracelyn CablayNo ratings yet

- Ge006 Utilitarianism RecordingDocument17 pagesGe006 Utilitarianism Recordingqrztg9kvq5No ratings yet

- 01-Joint Bidding Agreement - PMC EmpanelmentDocument4 pages01-Joint Bidding Agreement - PMC EmpanelmentDeva NaiduNo ratings yet

- #3 Environment Social Responsibility and Ethics of The FirmDocument29 pages#3 Environment Social Responsibility and Ethics of The FirmJoanna GarciaNo ratings yet

- Decision Making in Small Groups To Organize Your Community GardenDocument3 pagesDecision Making in Small Groups To Organize Your Community GardenAoede Arethousa100% (1)

- The Old-Fashioned WayDocument1 pageThe Old-Fashioned WayCallumNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Motivating Different Generations: Our Employees, Our FutureDocument5 pagesUnderstanding and Motivating Different Generations: Our Employees, Our FutureRoman AncaNo ratings yet

- JBT To TGT Medical Promotion Orders HP Feb 17 by Vijay Kumar HeerDocument8 pagesJBT To TGT Medical Promotion Orders HP Feb 17 by Vijay Kumar HeerVIJAY KUMAR HEERNo ratings yet

- English Focus: Educating The Literary Taste by Paz LatorenaDocument3 pagesEnglish Focus: Educating The Literary Taste by Paz LatorenaREGINE COELI LANSANGANNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow: Academic Session: 2017 - 18Document10 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow: Academic Session: 2017 - 18Aditi VatsaNo ratings yet

- NIL - Material Alteration & Forgery PDFDocument3 pagesNIL - Material Alteration & Forgery PDFAve Chaeza0% (1)

- Zobel Kayla ResumeDocument2 pagesZobel Kayla Resumeapi-309909634No ratings yet

- Oman Penal Code (1974/7)Document25 pagesOman Penal Code (1974/7)Social Media Exchange Association100% (2)

- I Carry You Heart With MeDocument2 pagesI Carry You Heart With MeIovanescu Andrada Diana100% (1)

- Music in IslamDocument3 pagesMusic in IslamMohammed faisalNo ratings yet

- Legal and Ethical Issues in NursingDocument6 pagesLegal and Ethical Issues in NursingCharm TanyaNo ratings yet

- BOC 2014 - Civil Law ReviewerDocument481 pagesBOC 2014 - Civil Law Reviewerjulieanne07No ratings yet

- Coexistence of I & BodyDocument2 pagesCoexistence of I & BodyrshauryaNo ratings yet

- 18) Virgilio Del Rosario Et Al., vs. Court of AppealsDocument1 page18) Virgilio Del Rosario Et Al., vs. Court of AppealsAngelica YatcoNo ratings yet

- Vienna and The Vienna MemorandumDocument46 pagesVienna and The Vienna MemorandumlalecrimNo ratings yet

- Summary M Carlos V AM Carlos and A Lucian V A LucianDocument6 pagesSummary M Carlos V AM Carlos and A Lucian V A LucianAndré Le RouxNo ratings yet

- Communication Process, Principles and EthicsDocument19 pagesCommunication Process, Principles and EthicsMichelle BalaoingNo ratings yet

- Two-Parent HomesDocument11 pagesTwo-Parent Homesapi-359734115No ratings yet

- Ann Hartle-Michel de Montaigne - Accidental Philosopher-Cambridge University Press (2003)Document313 pagesAnn Hartle-Michel de Montaigne - Accidental Philosopher-Cambridge University Press (2003)Sandra RamirezNo ratings yet

- Sample Proby Contract With Added ProvisionDocument5 pagesSample Proby Contract With Added ProvisionAndrew Michael TiuNo ratings yet

- Objection To S.27 Evidence ActDocument2 pagesObjection To S.27 Evidence ActJacq JimNo ratings yet

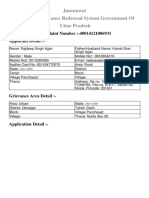

- JansunwaiDocument3 pagesJansunwaiDeepankaj KumarNo ratings yet

- SPA IrrevocableDocument4 pagesSPA IrrevocablejoshboracayNo ratings yet