Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robert Browning (1812 - 1889) : My Last Duchess

Robert Browning (1812 - 1889) : My Last Duchess

Uploaded by

CHHANDAM DEB0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views12 pagesThe poem "My Last Duchess" is narrated by the Duke of Ferrara who is showing a guest a portrait of his late wife, the Duchess. The Duke reveals that he had the previous Duchess killed because she was too friendly and easily impressed, smiling at everyone who passed. He insists on having complete control and will not tolerate any behavior he disapproves of. The Duke then changes the subject to discuss acquiring his next wife for her dowry and shows the guest a bronze statue, though the details he shared about his former Duchess portray him as egotistical and ruthless.

Original Description:

Browning's My Last Duchess Text, Explanation & PPT. presentation

Original Title

Browning

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe poem "My Last Duchess" is narrated by the Duke of Ferrara who is showing a guest a portrait of his late wife, the Duchess. The Duke reveals that he had the previous Duchess killed because she was too friendly and easily impressed, smiling at everyone who passed. He insists on having complete control and will not tolerate any behavior he disapproves of. The Duke then changes the subject to discuss acquiring his next wife for her dowry and shows the guest a bronze statue, though the details he shared about his former Duchess portray him as egotistical and ruthless.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

19 views12 pagesRobert Browning (1812 - 1889) : My Last Duchess

Robert Browning (1812 - 1889) : My Last Duchess

Uploaded by

CHHANDAM DEBThe poem "My Last Duchess" is narrated by the Duke of Ferrara who is showing a guest a portrait of his late wife, the Duchess. The Duke reveals that he had the previous Duchess killed because she was too friendly and easily impressed, smiling at everyone who passed. He insists on having complete control and will not tolerate any behavior he disapproves of. The Duke then changes the subject to discuss acquiring his next wife for her dowry and shows the guest a bronze statue, though the details he shared about his former Duchess portray him as egotistical and ruthless.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pptx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 12

Robert Browning (1812 –

1889)

My Last Duchess

Dr. Chhandam Deb

Head, Dept. Of English,

J.K. College, Purulia, WB, India

Introductory : 1

• First appeared in ‘Dramatic Lyrics’ in 1842

• 56 lines : 28 rhymed couplets

• The poem is preceded by the word "Ferrara", indicating that

the speaker is presumably Alfonso II d’Este (1533-58) belonging

to the Este family), the fifth Duke of Ferrara

• In 1558, at the age of 25, he married Lucrezia di Cosimo de’

Medici, the 14-year-old daughter of Cosimo de Medici, the

Grand Duke of Tuscany, who came with a large dowry

• Lucrezia : less educated; Medicis : considered ‘Nouve riche’

• ‘Nouve riche’ : a derogatory term : whose wealth acquired in

their own generation, rather than by inheritance

• Lucrezia abandoned for 2 years; died in 1561 (17 years old)

• Strong popular suspicion of poisoning, but it is more likely that

the cause of her death was tuberculosis

Dramatic Monologue

• Gk. ‘drao’: Action (drama); ‘Mono’: Single; ‘Logos’: Speech

• Elements of Drama, Lyric & Monologue combined together

• Seemingly personal; but a record of social interaction

• The second person in the poem : the Listener/Audience

• Listener : silent but not passive; he/she controls the speaker

• Listener: Interlocutor: responsive, & influences the speaker

• Irony : a potent instrument : discrepancy : Real & Apparent

• The poem – a perfect dramatic monologue : Action,

Character-revelation, Setting & Irony – all present

• Conversational style : intensifies the dramatic effect

• Heroic couplet used; but the rhymes are deliberately

muffled and confused : effect of run-on lines / blank verse

Portrait of Lucrezia (di Cosimo) de' Medici attributed to Agnolo di Bronzino

(Italian Mannerist painter of 16th century from Florence)

My Last Duchess (Ferrara)

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Fra Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said

“Fra Pandolf” by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus.

Sir, ’twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek: perhaps

Fra Pandolf chanced to say “Her mantle laps

Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat”: such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart—how shall I say?—too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace—all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men,—good! but thanked

Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift.

Who’d stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech—(which I have not)—to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

—E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose

Never to stoop.

Oh sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master’s known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

Some Insights

• ‘Ferrara’: City in lower Lombardy: home of Este family (13c.–16c.)

• The setting Browning’s knowledge of the Italian Renaissance

• Showing the envoy the painting of the Lady : Exhibitionist

• The painting : the power of the artist : ‘as if she were alive’.

• The painting reflects the magic of Italian Renaissance Art

• Exhibition of the painting/picture serves a dual purpose :

Projecting the character of the Duchess (Duke’s viewpoint)

Establishing a code of behaviour fit for the Este family Duchesses

3 actions :

The Duke shows the portrait to the envoy

The Duke describes the character of the Duchess

Showing the bronze statue of Neptune taming the sea-horse

Some Insights (contd.)

• Meanwhile, we are exposed to the quintessence of Feudalism :

The artistic collection of the Duke’s palace; his aesthetic taste;

and the ruthless, greedy and murderous character of the Duke

• Irony : an instrument of character portrayal : Duke & Duchess

• Irony generates a shift in perspective : hidden becomes exposed

• Peripeteia, or Reversal, of intention : the Duke ends up with just

the opposite of what he had intended (concealing his inner self)

• Contrast & Tension created by Irony : Appearance vs. Reality

• The Duke’s intention to win a bargain; yet he ultimately loses

• Portrayal of the Duchess as a misfit for aristocracy; light-hearted;

but the Duchess comes out as simple-hearted and innocent

• Betrayal of intention : Duke appears as egoistic & ruthless

• Neptune taming horse : ironical symbol of the dominating Duke

Thank You!

You might also like

- The OXford Dictionary of Literary Terms (3 Ed)Document1 pageThe OXford Dictionary of Literary Terms (3 Ed)yonseienglish33% (3)

- Commonlit My Last DuchessDocument5 pagesCommonlit My Last Duchessapi-506044294No ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument3 pagesMy Last DuchessChandan V ChanduNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument2 pagesMy Last Duchessraab167% (6)

- Aleister Crowley - AlexandraDocument12 pagesAleister Crowley - AlexandraChristina Debes100% (1)

- PoetsbiographyDocument4 pagesPoetsbiographyapi-319538724No ratings yet

- (Cambridge Studies in African and Caribbean Literature) Gregson Davis - Aime Cesaire-Cambridge University Press (1997) PDFDocument224 pages(Cambridge Studies in African and Caribbean Literature) Gregson Davis - Aime Cesaire-Cambridge University Press (1997) PDFDaniel Domingo GómezNo ratings yet

- Documents of West Indian HistoryDocument14 pagesDocuments of West Indian Historykarmele91No ratings yet

- Robert BrowningDocument9 pagesRobert BrowningM A R Y A M C HNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument4 pagesMy Last DuchessAlexandra Raluca RösslerNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument13 pagesMy Last DuchessArun GunasekaranNo ratings yet

- Dramatic MonologueDocument10 pagesDramatic MonologueSoham BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document13 pagesLecture 3snsd13477No ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument22 pagesMy Last Duchessapi-32677216No ratings yet

- My Last Duchess: by Robert BrowningDocument17 pagesMy Last Duchess: by Robert BrowningMatthew SalongaNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument15 pagesMy Last DuchessKay RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Poetic Genres: Robert Browning, "My Last Duchess"Document5 pagesPoetic Genres: Robert Browning, "My Last Duchess"Emalaith BlackburnNo ratings yet

- English Literature Lecture Note Final Term Blank VerseDocument4 pagesEnglish Literature Lecture Note Final Term Blank VerseAngela Rose BanastasNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument21 pagesMy Last DuchessAcNo ratings yet

- Critical AnalysisDocument5 pagesCritical AnalysisMuhammad YousafNo ratings yet

- Lyric Poetry: Types and Examples: Dying by Emily DickinsonDocument16 pagesLyric Poetry: Types and Examples: Dying by Emily DickinsonJeresse Jeah RecaforteNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument10 pagesMy Last DuchessFaisal Sharif100% (1)

- Virtual University of Pakistan ENG 401 Handouts Lecture 14Document7 pagesVirtual University of Pakistan ENG 401 Handouts Lecture 14ImranNo ratings yet

- My Last Duchess' by Robert Browning My Last Duchess' by Robert BrowningDocument20 pagesMy Last Duchess' by Robert Browning My Last Duchess' by Robert BrowningMindselo BeatsNo ratings yet

- PKPMRkIa - Kopija PDFDocument9 pagesPKPMRkIa - Kopija PDFJelena MarkovicNo ratings yet

- Marriage A La Mode: “Better shun the bait, than struggle in the snare. ”From EverandMarriage A La Mode: “Better shun the bait, than struggle in the snare. ”No ratings yet

- Duchessofmalfipl 00 WebsuoftDocument184 pagesDuchessofmalfipl 00 WebsuoftTolstoy LeoNo ratings yet

- The Duchess of MalfiDocument189 pagesThe Duchess of MalfiNithin BadiNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument3 pagesMy Last Duchessapi-237159930No ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument20 pagesMy Last DuchessSaja MahmoudNo ratings yet

- Eighteenth Century Literature: - Literature of The Augustan Period - Development of Satire - The Rise of The NovelDocument19 pagesEighteenth Century Literature: - Literature of The Augustan Period - Development of Satire - The Rise of The NovelMartaCampilloNo ratings yet

- To Delia & The Complaint of Rosamund: 'Love is a sickness full of woes, all remedies refusing''From EverandTo Delia & The Complaint of Rosamund: 'Love is a sickness full of woes, all remedies refusing''No ratings yet

- Aphra Behn RoverDocument22 pagesAphra Behn RoverHuman Journal of Literature and HumanitiesNo ratings yet

- The Provok'd Husband: 'Love, like virtue, is its own reward''From EverandThe Provok'd Husband: 'Love, like virtue, is its own reward''No ratings yet

- Activity1 - Analysis of The PoemDocument6 pagesActivity1 - Analysis of The PoemBona Marie G. BanariaNo ratings yet

- The Duchess of MalfiDocument187 pagesThe Duchess of MalfiSukanta MandalNo ratings yet

- The Imposture: “Knaves will thrive when honest plainness knows not how to live”From EverandThe Imposture: “Knaves will thrive when honest plainness knows not how to live”No ratings yet

- Revision Notes On The PoemsDocument98 pagesRevision Notes On The PoemsabasfordNo ratings yet

- My Last Duchess Is A Dramatic Monologue Set in Renaissance Italy (Early 16th Century)Document6 pagesMy Last Duchess Is A Dramatic Monologue Set in Renaissance Italy (Early 16th Century)Mazilu AdelinaNo ratings yet

- PoetryDocument18 pagesPoetryAnushka RanjanNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument5 pagesMy Last DuchessBhuvnesh MehruNo ratings yet

- JOHN DRYDEN Epilogue To The Conquest of GranadaDocument14 pagesJOHN DRYDEN Epilogue To The Conquest of GranadaJorge VargasNo ratings yet

- The Early Poems of Alfred Lord Tennyson - Volume III: "Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all."From EverandThe Early Poems of Alfred Lord Tennyson - Volume III: "Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all."No ratings yet

- Types of PoetryDocument33 pagesTypes of PoetryCeedy LaoNo ratings yet

- The Poems and Prose of Ernest Dowson, With a Memoir by Arthur SymonsFrom EverandThe Poems and Prose of Ernest Dowson, With a Memoir by Arthur SymonsNo ratings yet

- The Lover's Watch: "One hour of right-down love is worth an age of dully living on."From EverandThe Lover's Watch: "One hour of right-down love is worth an age of dully living on."No ratings yet

- Pair of Blue EyesDocument406 pagesPair of Blue Eyesana maksimovskaNo ratings yet

- Duke CharacterDocument5 pagesDuke CharacterSaba Parveen100% (3)

- My Last DuchessDocument10 pagesMy Last DuchessFront RowNo ratings yet

- Group 7 OralDocument19 pagesGroup 7 OralAimi Syafiqah GhazaliNo ratings yet

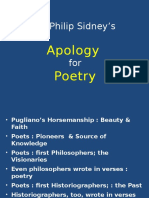

- Sir Philip Sidney's: Apology PoetryDocument19 pagesSir Philip Sidney's: Apology PoetryCHHANDAM DEBNo ratings yet

- TIRESIUSDocument10 pagesTIRESIUSCHHANDAM DEBNo ratings yet

- Macbeth As A Tragic HeroDocument1 pageMacbeth As A Tragic HeroCHHANDAM DEB100% (2)

- Welcome: Elizabethan Theatre: The Morality StructureDocument11 pagesWelcome: Elizabethan Theatre: The Morality StructureCHHANDAM DEBNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of The Absurd: The BasicsDocument18 pagesThe Theatre of The Absurd: The BasicsCHHANDAM DEBNo ratings yet

- Satan's CharacterDocument1 pageSatan's CharacterCHHANDAM DEBNo ratings yet

- Paradise Lost As An EpicDocument2 pagesParadise Lost As An EpicCHHANDAM DEBNo ratings yet

- Epic - Invocation - in Paradise Lost.Document2 pagesEpic - Invocation - in Paradise Lost.CHHANDAM DEBNo ratings yet

- HIndi PoemsDocument24 pagesHIndi PoemsSujit DwiNo ratings yet

- By Ted HughesDocument9 pagesBy Ted HughesSiyao He100% (1)

- I Ching - SCAN (179pp)Document179 pagesI Ching - SCAN (179pp)mrot100% (6)

- Helen Mor - Paper 2 - BaldwinDocument10 pagesHelen Mor - Paper 2 - BaldwinHelen MoriNo ratings yet

- Blue Bells ScotlandDocument1 pageBlue Bells ScotlandVanessa Baldocchi Home EvidenceNo ratings yet

- Browning As A Philosophical and Religions Teacher 1000094290 PDFDocument385 pagesBrowning As A Philosophical and Religions Teacher 1000094290 PDFMohammad WaseemNo ratings yet

- 283PPT (FigureofSpeech)Document78 pages283PPT (FigureofSpeech)Komal TiwariNo ratings yet

- English Advanced Technique ListDocument31 pagesEnglish Advanced Technique ListMatthew ChengNo ratings yet

- The Lake Isle of InnisfreeDocument18 pagesThe Lake Isle of Innisfreeapi-236470498No ratings yet

- 1) Thought FoxDocument4 pages1) Thought FoxAik AwaazNo ratings yet

- National Symbols of India and Their MeaningDocument5 pagesNational Symbols of India and Their Meaningapi-336751272No ratings yet

- A La Juventud FilipinaDocument7 pagesA La Juventud FilipinaDiana AcostaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Literature During The Spanish Colonial Period 1521Document5 pagesPhilippine Literature During The Spanish Colonial Period 1521Shannen PerezNo ratings yet

- S II. Lesson I. Mechanics of Writing. StudentsDocument7 pagesS II. Lesson I. Mechanics of Writing. Studentsslamalina935No ratings yet

- Pre-Reading: 1. Storm Soundscape: Teaching NotesDocument5 pagesPre-Reading: 1. Storm Soundscape: Teaching NotesJl WinterNo ratings yet

- Week 1 - Epic of Gilgamesh PDFDocument3 pagesWeek 1 - Epic of Gilgamesh PDFAngelo Von N. AdiaoNo ratings yet

- Meera BaiDocument2 pagesMeera BaiArvindChauhanNo ratings yet

- Flowering of Regional CulturesDocument8 pagesFlowering of Regional CulturesRiddhiman BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Odysseus Hero or NotDocument3 pagesOdysseus Hero or Notapi-241685119No ratings yet

- Guillermo Arriaga Screenwriting MasterclassDocument3 pagesGuillermo Arriaga Screenwriting MasterclassCarlos Castillo Palma100% (3)

- Dalit Studies-1Document5 pagesDalit Studies-1JennyRowenaNo ratings yet

- Lyric and Epic PoetryDocument1 pageLyric and Epic PoetryFranklyn Rañez GisulturaNo ratings yet

- UphillDocument66 pagesUphillapi-3773530100% (1)

- Syarat Pertandingan CHORAL SPEAKING 2019Document2 pagesSyarat Pertandingan CHORAL SPEAKING 2019Raihan Shamsudin100% (1)

- Stopping By+ Loveliest of TreesDocument11 pagesStopping By+ Loveliest of TreesEmpressMay ThetNo ratings yet

- Write An Exposition or Discussion On A Familiar Issue TO Include KEY Structural Elements and Language FeatureDocument25 pagesWrite An Exposition or Discussion On A Familiar Issue TO Include KEY Structural Elements and Language FeatureTrixie San Diego100% (2)