Professional Documents

Culture Documents

323 Morphology: The Structure of Words

323 Morphology: The Structure of Words

Uploaded by

Renjie OliverosCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Lexis and Structure Practice QuestionsDocument2 pagesLexis and Structure Practice Questionsfemi ade100% (2)

- An Overview of The English Morphological SystemDocument7 pagesAn Overview of The English Morphological SystemLucas Amâncio Mateus67% (3)

- Lecture 2Document8 pagesLecture 2Катeрина КотовичNo ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelaksanaan AktivitiDocument3 pagesRancangan Pelaksanaan AktivitiSiti Najwa ZainalNo ratings yet

- A Word and Its Forms - Inflections - SlidesDocument13 pagesA Word and Its Forms - Inflections - Slideszelindaa75% (4)

- Inflectional MorphologyDocument10 pagesInflectional MorphologyТамара ГроздановскиNo ratings yet

- FileContent 9Document103 pagesFileContent 9Samadashvili ZukaNo ratings yet

- The Teaching Profession Chapter 2Document54 pagesThe Teaching Profession Chapter 2Renjie Oliveros75% (4)

- English Grammar Workbook For Thai StudentsDocument60 pagesEnglish Grammar Workbook For Thai StudentsMieder van Loggerenberg100% (1)

- Pub - Teach Yourself Instant French With Audio PDFDocument127 pagesPub - Teach Yourself Instant French With Audio PDFMathias RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 323 Morphology 2Document12 pages323 Morphology 2Febri YaniNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Morphemes in Terms of Their Distribution in A Word and Their PropertiesDocument5 pagesAnalysis of Morphemes in Terms of Their Distribution in A Word and Their PropertiesAtiq AslamNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument14 pagesMorphologyAhmad FaragNo ratings yet

- 1 Morphology - Yule, 2010Document4 pages1 Morphology - Yule, 2010Dany Espinal MorNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument11 pagesMorphologyKenia AyalaNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument27 pagesMorphologyArriane ReyesNo ratings yet

- Morphological Structure of A Word. Word-Formation in Modern English 1. Give The Definition of The MorphemeDocument22 pagesMorphological Structure of A Word. Word-Formation in Modern English 1. Give The Definition of The MorphemeIvan BodnariukNo ratings yet

- AffixesDocument3 pagesAffixesGianina Rosas PillpeNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 - TYPES OF MORPHEMEDocument5 pagesLecture 2 - TYPES OF MORPHEMEkhadija seherNo ratings yet

- Makalah Morphology PDFDocument13 pagesMakalah Morphology PDFTiara WardoyoNo ratings yet

- Lexicology KonspektDocument52 pagesLexicology KonspektsovketrecebNo ratings yet

- Morphophonology (Also Morphophonemics, Morphonology) Is A Branch of Linguistics WhichDocument7 pagesMorphophonology (Also Morphophonemics, Morphonology) Is A Branch of Linguistics WhichJemario Mestika GurusingaNo ratings yet

- Morphology: The Analysis of Word Structure: Near) Encode Spatial RelationsDocument6 pagesMorphology: The Analysis of Word Structure: Near) Encode Spatial RelationsYašmeeñę ŁębdNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of MorphologyDocument10 pagesBasic Concepts of MorphologyI Nyoman Pasek DarmawanNo ratings yet

- English Morphology - Notes PDFDocument83 pagesEnglish Morphology - Notes PDFGeorge Petre100% (4)

- Morphology NotesDocument19 pagesMorphology Notesmuhammad faheem100% (1)

- Content Words and Structure WordsDocument4 pagesContent Words and Structure WordsdeepkrishnanNo ratings yet

- Word Parts GuideDocument6 pagesWord Parts GuideRya EarlNo ratings yet

- Unit 10: Lexis. Characteristics of Word Formation in English. Prefixation, Suffixation and CompoundingDocument14 pagesUnit 10: Lexis. Characteristics of Word Formation in English. Prefixation, Suffixation and CompoundingDave MoonNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of ADocument5 pagesLinguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of AChiara Di nardoNo ratings yet

- Morphology 2 by Yule George (2007)Document6 pagesMorphology 2 by Yule George (2007)afernandezberrueta67% (3)

- Chapter 4Document6 pagesChapter 4vimincryNo ratings yet

- Parts of SpeechDocument11 pagesParts of Speechneeraj punjwaniNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Types of Words and Word Formation ProcessesDocument23 pagesUnit 1 Types of Words and Word Formation ProcessesAhmed El-SaadanyNo ratings yet

- Taking Words ApartDocument7 pagesTaking Words ApartSharynaNo ratings yet

- Speech Sounds Phonetics: Is The Study of Speech SoundsDocument9 pagesSpeech Sounds Phonetics: Is The Study of Speech SoundsIvete MedranoNo ratings yet

- Morphology WorksheetDocument9 pagesMorphology WorksheetCristian David Olarte GomezNo ratings yet

- MORPHOLOGYDocument11 pagesMORPHOLOGYnguyenthikieuvanNo ratings yet

- Cultural Patterns and ProcessesDocument32 pagesCultural Patterns and Processesngan ping pingNo ratings yet

- - - نحو نورمان استاكبيرغ -Document32 pages- - نحو نورمان استاكبيرغ -Mohammed GallawiNo ratings yet

- Albe C. Nopre Jr. CE11KA2: VerbalsDocument5 pagesAlbe C. Nopre Jr. CE11KA2: VerbalsAlbe C. Nopre Jr.No ratings yet

- Understanding Morphology Second EditionDocument14 pagesUnderstanding Morphology Second EditionJulia TamNo ratings yet

- A Meaningful Morphological Unit of A Language That Cannot Be Further Divided (E.g., In, Come, - Ing, Forming Incoming)Document4 pagesA Meaningful Morphological Unit of A Language That Cannot Be Further Divided (E.g., In, Come, - Ing, Forming Incoming)Liljana DimeskaNo ratings yet

- перероблений семінар 2, ЛA-02, Grubiak YuliaDocument8 pagesперероблений семінар 2, ЛA-02, Grubiak YuliaЮлия ГрубякNo ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument29 pagesWord Formationpololopi75% (4)

- Dissimilation Draft2Document46 pagesDissimilation Draft2Chris JhnNo ratings yet

- 18men14c U3Document10 pages18men14c U3K. RAMYANo ratings yet

- Procedures Step1: Preparation (Pre-Assessment Activity/ Brain Storming)Document15 pagesProcedures Step1: Preparation (Pre-Assessment Activity/ Brain Storming)abida jamaliNo ratings yet

- Word RootsDocument18 pagesWord Rootshpeter195798No ratings yet

- Descriptive GrammarDocument47 pagesDescriptive GrammarIgor DudzikNo ratings yet

- When We Talk About Lexical UnitsDocument2 pagesWhen We Talk About Lexical UnitsJEFFERSON BRYAN CUASQUE PABONNo ratings yet

- Derivational and Functional AffixesDocument7 pagesDerivational and Functional AffixesNicole PaladaNo ratings yet

- Morphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsDocument6 pagesMorphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsKai KokoroNo ratings yet

- Ref Chap3 CADocument4 pagesRef Chap3 CATuyền LêNo ratings yet

- KLP 5 Resume MorfologiDocument2 pagesKLP 5 Resume MorfologiMuflyh AhmadNo ratings yet

- English Morphology and Lexicology Unit 1:: Word FormationDocument27 pagesEnglish Morphology and Lexicology Unit 1:: Word FormationTuấn Minh Nguyễn PhúNo ratings yet

- Referat - Verbe EnglezaDocument25 pagesReferat - Verbe Englezalil_emy18No ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument6 pagesWord FormationAiganymNo ratings yet

- Morphological Structure of English WordsDocument20 pagesMorphological Structure of English Wordserke.amangazhyNo ratings yet

- Terms and Definitions of Word FormationDocument9 pagesTerms and Definitions of Word FormationNURUL AIN NABIILAHNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: Morphology: Yes Has No Internal Grammatical Structure. We Could Analyse ItsDocument8 pagesUnit 1: Morphology: Yes Has No Internal Grammatical Structure. We Could Analyse ItsThúy HiềnNo ratings yet

- A Morphology Group 3Document42 pagesA Morphology Group 3037 Deffani Putri NandikaNo ratings yet

- Pertemuan 5 - WordsDocument7 pagesPertemuan 5 - WordsAnnisaNurulFadilahNo ratings yet

- The Etymology and Syntax of the English Language: Explained and IllustratedFrom EverandThe Etymology and Syntax of the English Language: Explained and IllustratedNo ratings yet

- 12 PartsofanewsletterDocument29 pages12 PartsofanewsletterRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- The Teaching Profession Chapter 2Document54 pagesThe Teaching Profession Chapter 2Renjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- 1 Nature of StatisticsDocument26 pages1 Nature of StatisticsRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- 2 Frequency Distribution and GraphsDocument9 pages2 Frequency Distribution and GraphsRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Chinese Mythology: Reported By: Renjie D. OliverosDocument21 pagesChinese Mythology: Reported By: Renjie D. OliverosRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Arabian LiteratureDocument29 pagesArabian LiteratureRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Marie Curie BiographyDocument5 pagesMarie Curie BiographyRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Allomorphy andDocument33 pagesAllomorphy andRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- RPT Math DLP Year 3 2023-2024Document23 pagesRPT Math DLP Year 3 2023-2024Firdaussi HashimNo ratings yet

- PHIL-IRI CLASS READING PROFILE SampleDocument24 pagesPHIL-IRI CLASS READING PROFILE SampleAldrin Ayuno LabajoNo ratings yet

- Close-Up - B1+ - Extra Vocabulary and Grammar Tasks KeyDocument3 pagesClose-Up - B1+ - Extra Vocabulary and Grammar Tasks Keymajidalbadawi687100% (3)

- Grammar Worksheets 47Document2 pagesGrammar Worksheets 47santhawdar wintNo ratings yet

- Tiny Tokyo Apartments - Intermediate News LessonDocument8 pagesTiny Tokyo Apartments - Intermediate News LessonBarbariskovna IriskaNo ratings yet

- Academic Essays: Form and Function: The Structure of A 1000-3000 Word EssayDocument2 pagesAcademic Essays: Form and Function: The Structure of A 1000-3000 Word EssayNgô Hoàng Bích KhaNo ratings yet

- LanguagesDocument18 pagesLanguagesKHUSHI ANSARINo ratings yet

- Karnataka Class 10 English Solutions Chapter 1 A Wrong Man in Workers' Paradise - KSEEB SolutionsDocument19 pagesKarnataka Class 10 English Solutions Chapter 1 A Wrong Man in Workers' Paradise - KSEEB SolutionsS C Prajwal80% (5)

- Ni Luh Leoni Kartika (0176)Document3 pagesNi Luh Leoni Kartika (0176)leoni kartikaNo ratings yet

- Present Perfect and Simple Past ExerciseDocument10 pagesPresent Perfect and Simple Past ExerciseSimhadri MadhuriNo ratings yet

- Module 1 in ENG213DDocument9 pagesModule 1 in ENG213DLJSCNo ratings yet

- Translation As An ActivityDocument34 pagesTranslation As An ActivityGulasal HosinovaNo ratings yet

- Present Simple - Negative & QuestionsDocument5 pagesPresent Simple - Negative & QuestionsAna CruzNo ratings yet

- Comm Skills (Pasco) Prof KayDocument6 pagesComm Skills (Pasco) Prof KayChristopher ArthurNo ratings yet

- The Oxford English DictionaryDocument12 pagesThe Oxford English DictionaryMiguel Salvador Medina GervasioNo ratings yet

- Academy Stars 5 WB Unit 1Document9 pagesAcademy Stars 5 WB Unit 1Laura ChajturaNo ratings yet

- Verbs Noun Adjective AdverbDocument19 pagesVerbs Noun Adjective AdverbDariaNo ratings yet

- Hieroglyphs On Bone Ivory Tags of AbydosDocument6 pagesHieroglyphs On Bone Ivory Tags of AbydosSarah BernsdorffNo ratings yet

- Lgs Personal Lesson Plan 20-21 Half YearlyDocument3 pagesLgs Personal Lesson Plan 20-21 Half Yearlymasudur rahmanNo ratings yet

- There: It Generally Refers To Something Already Mentioned. There Is Used With BeDocument2 pagesThere: It Generally Refers To Something Already Mentioned. There Is Used With BeELENANo ratings yet

- Ovando, C.J. Et. Al. Bilingual & ESL Classrooms-Teaching in Multicultural ContextsDocument6 pagesOvando, C.J. Et. Al. Bilingual & ESL Classrooms-Teaching in Multicultural ContextsOlga KardashNo ratings yet

- Critical Reading Week 15 Assignment - Fathul Mubarak (19018059) K2-19Document3 pagesCritical Reading Week 15 Assignment - Fathul Mubarak (19018059) K2-19Fathul MubarakNo ratings yet

- Inglés II, Primera Edición, Yaneth Ocando Pereira - 1 - Unidad IDocument18 pagesInglés II, Primera Edición, Yaneth Ocando Pereira - 1 - Unidad IJhohanes OrtizNo ratings yet

- It's All Your Fault!: If You Had Filled The Car With Petrol, It Wouldn't Have Stopped!Document2 pagesIt's All Your Fault!: If You Had Filled The Car With Petrol, It Wouldn't Have Stopped!Predrag MaksimovicNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Language and SymbolsDocument4 pagesMathematical Language and SymbolsRachel Anne BodlisNo ratings yet

- Stylistic Classification of The English VocabularyDocument58 pagesStylistic Classification of The English VocabularyDiana ShevchukNo ratings yet

323 Morphology: The Structure of Words

323 Morphology: The Structure of Words

Uploaded by

Renjie OliverosOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

323 Morphology: The Structure of Words

323 Morphology: The Structure of Words

Uploaded by

Renjie OliverosCopyright:

Available Formats

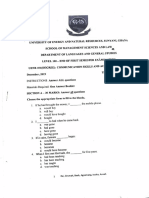

323 Morphology

The Structure of Words

2. Basic Concepts

2.1 Lexemes and Word Forms

Words are not easy to define.

A preliminary definition is based on the English

orthographic system.

The spaces used in orthography represent words

(usually).

Most dictionaries list only one word of an inflected

set:

E.g. sing, sang, sung, singing, sings.

The form ‘sing’ is always chosen as a dictionary

entry.

The form is technically an infinitive.

In linguistics the term is lexeme represents the basic

or dictionary form of the word.

Lexemes are usually written in CAPS: SING

Lexemes are abstract representations, which presumably

are listed in the brain in a component called the

lexicon.

Each inflected form of a lexeme is called a word-form.

E.g. ‘sing, sang, sung, singing, sings’ are each a

word-form and each one belongs to the lexeme SING.

2.1 Lexemes and Word Forms

By convention in each language, the dictionary

representation may be the infinitive form of the verb as

in Russian, the first person singular in Latin (which has

no infinitive), the third person singular in Arabic, or

perhaps by some other form. The entry form for nouns in

normally the singular nominative case form of the noun:

Latin, Russian, English, Czech, German.

A lexeme family, or less formally a word family, is a set

of lexemes that are related. They should share some

phonological properties and be related semantically. The

latter is easier said than determined.

E.g. print, printable, unprintable, printer,

printability, reprint.

This list is not necessarily complete.

Complex lexemes are lexemes formed with an affix (a

morpheme).

E.g. ‘able’, ‘un’, ‘er’, ‘ity’, ‘re’ in the above

list.

Complex lexemes must each be listed separately in a

dictionary as the meaning may differ.

The various word-forms of a given lexeme do not change

the meaning of the lexeme.

2.1 Lexemes and Word Forms

Sometimes a lexeme with an affix occurs but the basic

form does not exist:

E.g. dis-gruntled but not *gruntled, in-cognito, but

not *cognito, un-gainly, but not*gainly.

Sometimes the expected affix does not occur but another

affix does:

E.g. natural-ness in place *natural-ity.

Or the expected affix occurs with another meaning:

E.g. cook, cook-er (an instrument for cooking, not a

person who cooks, which is simply the

noun ‘cook’.

Kinds of morphological relationship

inflection: the relationship between the word-forms of a

lexeme.

E. g. mask, masks; sit, sat, sitting, sits; blue,

bluer, bluest.

derivation: the relationship between lexemes of a

lexical family.

E. g. singer, singer; write, writer; cook V, cookN,

cooker.

Derivation usually implies forming one lexeme from another

lexeme in the same lexical family.

E.g. sing -> singer, write -> writer, cook V, cookN and

cooker.

2.2 Morphemes

A morpheme is the smallest constituent with a function. I prefer

this distinction to ‘smallest constituent with meaning. There are

some forms that appears to be constituents but have no

discernable meaning, but have a function in terms of word

building:

E.g. doof-us, radi-us, cf. radi-al, radi-an.

Some inflectional morphemes have no true meaning, but they have a

grammatical function:

E.g. he, him; who, whom; they, them,

The suffix ‘-m’ marks the accusative (objective) Case. This is a

syntactic relation and no meaning can be associated with it.

The term function includes meaning.

To go one step further than H., the hierarchy for constituents

is:

Sentence -> phrase -> word -> morpheme.

Phrases are very important constituents in syntax.

Some grammatical categories cannot be expressed in terms of

morphemes. For example, note the following partial inflection of

the English verb sing and others similar to it:

E.g. sing, sang, sung.

The past tense is marked by a change of the root vowel. The

latter form marks two distinct grammatical functions — the

2.3 Affixes, Bases and Roots

Affixes are morphemes that are adjoined to the left of the

base of a word or to the right of the base of a word:

A prefix is an affix that is adjoined to the left of the

base of a word.

E.g. ‘un-’ in un-happy, un-regulated; ‘re-’ re-do,

reheat, re-write, and so forth.

A suffix is an affix that is adjoined to the right of the

base of a word.

E.g. ‘s’ in book-s, cat-s; eat-s, smell-s;

linguistic-s.

An infix is an affix that is inserted into the base of

the word forming a non- contiguous base. There

are no infixes in English. Infixes occur in the Semitic

language.

E. g. “ktb” is the base for book and read and words

which refer to book/read in some

related sense. To form the noun in Arabic,

the infixes ‘I’ and ‘a’ are inserted into the base

between the firsts two consonants and the second two

consonants, respectively:

E.g. kitab.

A circumflex is an affix that occurs on both sides of the base.

(H.)

E. g. (per H) German ge-les-en.

English dialects: a-walk-ing, a-read-ing..

The English “a-” is etymologically related to the German

“ge-”.

2.3 Affixes, Bases and Roots

Stem and Root

A root is a morpheme that cannot be broken down into further

morphemes.

A base is a contiguous strings of one or more morphemes which can

hold lexical meaning.

In English the word dog, for example, is a root since it cannot be

broken into further morphological units:

E. g. ‘do’ is not a morpheme of dog, it is basically a

verb. There is no morpheme ‘og’ that has any kind of

function.

Dog is also a base. It has lexical meaning.

The English word disgruntled consists of three morpheme dis-, gruntle,

and ed. ‘dis’ is a prefix, and ed’ is an inflectional affix

marking the past tense among other functions. The morpheme gruntle

is a root, since two affixes are adjoined to it. It is not a base,

since it has no lexical meaning (what does gruntle mean?) Once

both affixes are adjoined to it, then disgruntled, which is a

base, is a lexical stem since it does have meaning.

Technically, the prefix ‘dis-’ is adjoined first to gruntle to form

the base ‘disgruntle’. Apparently this form has no lexical

meaning and remains a base. Once the adjectival suffix ‘-ed’ is

added to disgruntle then the base receives lexical meaning and is a

stem.

English has several words usually considered compounds, where at least

one member of the compound doesn’t behave like a normal prefix or

affix.

E. g. tele-graph. Although graph may have lexical meaning, tele-

does not. It does not occur in isolation. The form is borrowed from

2.4 Formal Operations

Some words such as derive imply a process. A true process is a

historical phenomenon and does not imply a process in terms of how

language is represented in the mind (the grammar of a language). For

some yet to be determined reason, H considers affixation and

compounding to be concatenative, but inflection and other

constructions he considers to be non-concatenative.

Another non-concatenative structure include word whose final consonant

becomes voiced, final consonant becomes palatalized, or gemination of

a root consonant.

E.g. Albanian: armik [-q] (Sg.), armiq [-c] (Pl.).

Note: [c] is not a palatalized consonant. The form came about

through palatalization, which is not

visible/hearable.

E.g. English: hoof [hƱf] (Sg.), hooves [hƱvz] (Pl.).

E.g. Arabic causative verbs: darasa (noncausative), darrasa

(causative). Gemination is the doubling of a consonant.

Reduplication is the copying of a syllable or part of a syllable:

1. Prereduplication:

E.g. Ponapean: duhp (nonprogressive), du-duhp (progressive) ‘(be)

diving.’

A weak syllable (no coda) is copied).

2. Postreduplication.

E.g. Mangap-Mbula: kuk (nonprogressive), kuk-uk )progressive)

‘(be) barking’

The rhyme of the syllable is copied.

3. Duplifixing is adding an affix and reduplicated part of the

stem:

2.4 Formal Operations

E.g. Tsutujil: saq (Sg.) ‘’white’, saq-soj ’whitish’.

‘s’ is reduplicated from the initial consonant of the stem, and ‘oj’ is a nonvariable suffix.

Subtraction is the omission of one or more final segments of the base.

E.g. Murle: nyoon (Sg.), nyoo (Pl.) ‘lamb’

Strong suppletion is replacing one form with another form (allomorph) that is phonologically

unrelated to it the replacee.

E.g. the forms of the English verb be: ‘is’, ‘are’, ‘was/were’.

Weak suppletion if replacing one form with another form (allomorph) which share some common

phonological forms, but not all phonological forms are common to both:

E.g. sing, sang (/I/, /æ/), foot, feet (/Ʊ/ /I/).

‘Base’ is redefined (H):

The base of a morphologically complex word is the element to which a morphological operation

applies.

This definition works a long as we assume a zero operation that may derive one form from

another forms is derived with no phonological change. We can say a base may be derived from

a root with a zero morphological operation.

E.g. the noun ‘push’ (he gave me a push) is derived from the verb ‘push’. The derivation is

a zero operation in that there is no overt sign marking this. We could represent this as:

[N[V PUSH]], probably in later chapters.

A morphological pattern refers to the various ways a particular grammatical or lexical feature can be

expressed. There are four morphological patterns of the past tense of the English verb:

E.g. the default suffix ’-ed’, the irregular suffix ‘-d’ (tell, told), ,the irregular suffix ‘-T (feel, felt),

and the vowel replacement system of strong verbs (sing, sang; drink, drank).

2.5 Morphemes and Allomorphs

A morpheme is a set of allomorphs. Most linguists would agree with this

even if they are not familiar with set theory. The problem is how to

account the variation. For the past 45 years or so, the theory of

underlying representation. This theory states that there is an abstract

(usually) form from which the other allomorphs are derived. H refers to

these as a ’fictitious underlying representation’ (p.27). H does not

elaborate here.

The approach that I favour is set theory.To review Korean, there are two

allomorphs (members) of the set for the plural of nouns: {ul, lul} (also

written as {{ul}, {lul}}. The standard to write morphemes and allomorphs

with hyphens to show that the morpheme or allomorph is an affix. I is not

a theoretical divergence. As I mentioned before one of the allomorphs of

the plural morpheme is the default. The nondefault allomorph must be

marked with information indicating the contexts in which the allomorph

occurs. The default allomorph usually corresponds with the underlying

form. The default or underlying allomorph is normally determined, in

part, at least, by is distribution. There are fewer vowels than

consonants in Korean. If -ul, which follows consonants, is the default,

then the selection of -lul has a more constrained condition. The rule

writing form will be dealt with later.

In the Russian example on p. 27, H considers ZAMOK-I castles to be the

underlying form for the plural form. The suffix ‘-ok’ must be marked in

its grammatical entry (the grammaticon) to indicate that the vowel /o/ in

the suffix /ok/ is deleted if the inflectional affix begins with a vowel.

I, too, would consider the allomorph /ok/ as the default. And I would

marked the other allomorph with the same information indicating that /k/

is chosen if the suffix begins with a vowel.

2.6 Some Problems in Morpheme Analysis

H mentions a problem arising from suppletion. The plural allomorphs ‘-s’ and

‘-en’ in English are related by suppletion. They share no exclusive

phonological properties. H raises the question whether the two suffixes are

manifestations of the same morpheme. H leans toward this view. So do I.

My view is determined by the claim that all morphemes must have a form, a

function and a sign. I will illustrate with the progressive participle

suffix ‘-ing’:

The program I am using to make graphics does not import unicode

phonetics. I am using here ‘ñ’ for engma, the nasal velar [ŋ].

[+Progressive] is the feature denoting the progressive aspect; the form

is a suffix which is adjoined to a noun host (base); and the sign is

/ɩŋ/.

There are plural signs for nouns in English: /z/ and /ɩn/. These two

allomorphs are strongly suppletive. They are shown in the following

grammeme (entry form for grammatical morphemes):

2.6 Some Problems in Morpheme Analysis

Grammeme: [+Pl]

[+Plural, Noun] function

+Suffix

+Host form

+Noun

{/in/, / {CHILD, BROTHER, OX} ___}, sign

{/iz/, [default]}

The two allomorphs here form a ‘natural’ set, since they share

the same function. The fact that they are the same form supports

this claim. If they are in the same set, then they must be a

member of the [+Pl]. And if they are in the same set they must be

allomorphs.

A morpheme may consist of two or more features. For example, the

English verbal suffix ‘-s’ marks agreement with a third person

singular subject and it marks the present tense. The suffix in the

above figure contains two subfeatures [+Host] and [+Noun].

Agglutinating languages do not do this, with some minor

exceptions. This cumulative expression is also called fusion.

A zero expression ‘ø’ means that there is no overt affix to mark a

function. ‘ø’ has been the topic of notable debates. Until very

recently I was opposed to the notion of ‘ø’ until I started

learning set theory. Set theory permits empty sets often written

as ‘ø’. A zero expression grammeme is not entirely empty; the sign

2.6 Some Problems in Morpheme Analysis

Grammeme: [-Pl, +Noun]

[-Plural, +Noun] function

ø form

ø sign

Only the function is not empty; it merely has no form and no

sign.

An empty morpheme is an affix that has no meaning, but has a

function: it forms a base to which certain meaningful affixes are

adjoined. This occurs in English when nouns are borrowed from

Greek and Latin and retain their plural form. The singular ending

occurs in English an empty (ø) morph:

E.g. radi-us (Sg.), radi-i (Pl.); agend-a (Sg.), agend-ae

(Pl.); phenomen-on (Sg.), phenomen-a (Pl.).

The plural form is adjoined to the base, respectively: ‘I’, ‘ae’,

‘a’. In English the Sg. form is morphologically null. The

suffixes in the above three examples are stem-enders, an empty

Grammeme:

morpheme required when there is no [stem extender]

suffix adjoined to the word.

This applies to derivatives as well: radi-al, phenomen-al, and

stem extender when function

so forth. The grammemical entry for ‘-us’ is:

there is no affix, 'us'

class

[+suffix] form

us sign

• Go to Course Outline, Go to Chapter 1, Go to Chapter 3

You might also like

- Lexis and Structure Practice QuestionsDocument2 pagesLexis and Structure Practice Questionsfemi ade100% (2)

- An Overview of The English Morphological SystemDocument7 pagesAn Overview of The English Morphological SystemLucas Amâncio Mateus67% (3)

- Lecture 2Document8 pagesLecture 2Катeрина КотовичNo ratings yet

- Rancangan Pelaksanaan AktivitiDocument3 pagesRancangan Pelaksanaan AktivitiSiti Najwa ZainalNo ratings yet

- A Word and Its Forms - Inflections - SlidesDocument13 pagesA Word and Its Forms - Inflections - Slideszelindaa75% (4)

- Inflectional MorphologyDocument10 pagesInflectional MorphologyТамара ГроздановскиNo ratings yet

- FileContent 9Document103 pagesFileContent 9Samadashvili ZukaNo ratings yet

- The Teaching Profession Chapter 2Document54 pagesThe Teaching Profession Chapter 2Renjie Oliveros75% (4)

- English Grammar Workbook For Thai StudentsDocument60 pagesEnglish Grammar Workbook For Thai StudentsMieder van Loggerenberg100% (1)

- Pub - Teach Yourself Instant French With Audio PDFDocument127 pagesPub - Teach Yourself Instant French With Audio PDFMathias RodriguezNo ratings yet

- 323 Morphology 2Document12 pages323 Morphology 2Febri YaniNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Morphemes in Terms of Their Distribution in A Word and Their PropertiesDocument5 pagesAnalysis of Morphemes in Terms of Their Distribution in A Word and Their PropertiesAtiq AslamNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument14 pagesMorphologyAhmad FaragNo ratings yet

- 1 Morphology - Yule, 2010Document4 pages1 Morphology - Yule, 2010Dany Espinal MorNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument11 pagesMorphologyKenia AyalaNo ratings yet

- MorphologyDocument27 pagesMorphologyArriane ReyesNo ratings yet

- Morphological Structure of A Word. Word-Formation in Modern English 1. Give The Definition of The MorphemeDocument22 pagesMorphological Structure of A Word. Word-Formation in Modern English 1. Give The Definition of The MorphemeIvan BodnariukNo ratings yet

- AffixesDocument3 pagesAffixesGianina Rosas PillpeNo ratings yet

- Lecture 2 - TYPES OF MORPHEMEDocument5 pagesLecture 2 - TYPES OF MORPHEMEkhadija seherNo ratings yet

- Makalah Morphology PDFDocument13 pagesMakalah Morphology PDFTiara WardoyoNo ratings yet

- Lexicology KonspektDocument52 pagesLexicology KonspektsovketrecebNo ratings yet

- Morphophonology (Also Morphophonemics, Morphonology) Is A Branch of Linguistics WhichDocument7 pagesMorphophonology (Also Morphophonemics, Morphonology) Is A Branch of Linguistics WhichJemario Mestika GurusingaNo ratings yet

- Morphology: The Analysis of Word Structure: Near) Encode Spatial RelationsDocument6 pagesMorphology: The Analysis of Word Structure: Near) Encode Spatial RelationsYašmeeñę ŁębdNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of MorphologyDocument10 pagesBasic Concepts of MorphologyI Nyoman Pasek DarmawanNo ratings yet

- English Morphology - Notes PDFDocument83 pagesEnglish Morphology - Notes PDFGeorge Petre100% (4)

- Morphology NotesDocument19 pagesMorphology Notesmuhammad faheem100% (1)

- Content Words and Structure WordsDocument4 pagesContent Words and Structure WordsdeepkrishnanNo ratings yet

- Word Parts GuideDocument6 pagesWord Parts GuideRya EarlNo ratings yet

- Unit 10: Lexis. Characteristics of Word Formation in English. Prefixation, Suffixation and CompoundingDocument14 pagesUnit 10: Lexis. Characteristics of Word Formation in English. Prefixation, Suffixation and CompoundingDave MoonNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of ADocument5 pagesLinguistic Signs, A Combination Between A Sound Image /buk/ or An Actual Icon of AChiara Di nardoNo ratings yet

- Morphology 2 by Yule George (2007)Document6 pagesMorphology 2 by Yule George (2007)afernandezberrueta67% (3)

- Chapter 4Document6 pagesChapter 4vimincryNo ratings yet

- Parts of SpeechDocument11 pagesParts of Speechneeraj punjwaniNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Types of Words and Word Formation ProcessesDocument23 pagesUnit 1 Types of Words and Word Formation ProcessesAhmed El-SaadanyNo ratings yet

- Taking Words ApartDocument7 pagesTaking Words ApartSharynaNo ratings yet

- Speech Sounds Phonetics: Is The Study of Speech SoundsDocument9 pagesSpeech Sounds Phonetics: Is The Study of Speech SoundsIvete MedranoNo ratings yet

- Morphology WorksheetDocument9 pagesMorphology WorksheetCristian David Olarte GomezNo ratings yet

- MORPHOLOGYDocument11 pagesMORPHOLOGYnguyenthikieuvanNo ratings yet

- Cultural Patterns and ProcessesDocument32 pagesCultural Patterns and Processesngan ping pingNo ratings yet

- - - نحو نورمان استاكبيرغ -Document32 pages- - نحو نورمان استاكبيرغ -Mohammed GallawiNo ratings yet

- Albe C. Nopre Jr. CE11KA2: VerbalsDocument5 pagesAlbe C. Nopre Jr. CE11KA2: VerbalsAlbe C. Nopre Jr.No ratings yet

- Understanding Morphology Second EditionDocument14 pagesUnderstanding Morphology Second EditionJulia TamNo ratings yet

- A Meaningful Morphological Unit of A Language That Cannot Be Further Divided (E.g., In, Come, - Ing, Forming Incoming)Document4 pagesA Meaningful Morphological Unit of A Language That Cannot Be Further Divided (E.g., In, Come, - Ing, Forming Incoming)Liljana DimeskaNo ratings yet

- перероблений семінар 2, ЛA-02, Grubiak YuliaDocument8 pagesперероблений семінар 2, ЛA-02, Grubiak YuliaЮлия ГрубякNo ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument29 pagesWord Formationpololopi75% (4)

- Dissimilation Draft2Document46 pagesDissimilation Draft2Chris JhnNo ratings yet

- 18men14c U3Document10 pages18men14c U3K. RAMYANo ratings yet

- Procedures Step1: Preparation (Pre-Assessment Activity/ Brain Storming)Document15 pagesProcedures Step1: Preparation (Pre-Assessment Activity/ Brain Storming)abida jamaliNo ratings yet

- Word RootsDocument18 pagesWord Rootshpeter195798No ratings yet

- Descriptive GrammarDocument47 pagesDescriptive GrammarIgor DudzikNo ratings yet

- When We Talk About Lexical UnitsDocument2 pagesWhen We Talk About Lexical UnitsJEFFERSON BRYAN CUASQUE PABONNo ratings yet

- Derivational and Functional AffixesDocument7 pagesDerivational and Functional AffixesNicole PaladaNo ratings yet

- Morphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsDocument6 pagesMorphology - Study of Internal Structure of Words. It Studies The Way in Which WordsKai KokoroNo ratings yet

- Ref Chap3 CADocument4 pagesRef Chap3 CATuyền LêNo ratings yet

- KLP 5 Resume MorfologiDocument2 pagesKLP 5 Resume MorfologiMuflyh AhmadNo ratings yet

- English Morphology and Lexicology Unit 1:: Word FormationDocument27 pagesEnglish Morphology and Lexicology Unit 1:: Word FormationTuấn Minh Nguyễn PhúNo ratings yet

- Referat - Verbe EnglezaDocument25 pagesReferat - Verbe Englezalil_emy18No ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument6 pagesWord FormationAiganymNo ratings yet

- Morphological Structure of English WordsDocument20 pagesMorphological Structure of English Wordserke.amangazhyNo ratings yet

- Terms and Definitions of Word FormationDocument9 pagesTerms and Definitions of Word FormationNURUL AIN NABIILAHNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: Morphology: Yes Has No Internal Grammatical Structure. We Could Analyse ItsDocument8 pagesUnit 1: Morphology: Yes Has No Internal Grammatical Structure. We Could Analyse ItsThúy HiềnNo ratings yet

- A Morphology Group 3Document42 pagesA Morphology Group 3037 Deffani Putri NandikaNo ratings yet

- Pertemuan 5 - WordsDocument7 pagesPertemuan 5 - WordsAnnisaNurulFadilahNo ratings yet

- The Etymology and Syntax of the English Language: Explained and IllustratedFrom EverandThe Etymology and Syntax of the English Language: Explained and IllustratedNo ratings yet

- 12 PartsofanewsletterDocument29 pages12 PartsofanewsletterRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- The Teaching Profession Chapter 2Document54 pagesThe Teaching Profession Chapter 2Renjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- 1 Nature of StatisticsDocument26 pages1 Nature of StatisticsRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- 2 Frequency Distribution and GraphsDocument9 pages2 Frequency Distribution and GraphsRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Chinese Mythology: Reported By: Renjie D. OliverosDocument21 pagesChinese Mythology: Reported By: Renjie D. OliverosRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Arabian LiteratureDocument29 pagesArabian LiteratureRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Marie Curie BiographyDocument5 pagesMarie Curie BiographyRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- Allomorphy andDocument33 pagesAllomorphy andRenjie OliverosNo ratings yet

- RPT Math DLP Year 3 2023-2024Document23 pagesRPT Math DLP Year 3 2023-2024Firdaussi HashimNo ratings yet

- PHIL-IRI CLASS READING PROFILE SampleDocument24 pagesPHIL-IRI CLASS READING PROFILE SampleAldrin Ayuno LabajoNo ratings yet

- Close-Up - B1+ - Extra Vocabulary and Grammar Tasks KeyDocument3 pagesClose-Up - B1+ - Extra Vocabulary and Grammar Tasks Keymajidalbadawi687100% (3)

- Grammar Worksheets 47Document2 pagesGrammar Worksheets 47santhawdar wintNo ratings yet

- Tiny Tokyo Apartments - Intermediate News LessonDocument8 pagesTiny Tokyo Apartments - Intermediate News LessonBarbariskovna IriskaNo ratings yet

- Academic Essays: Form and Function: The Structure of A 1000-3000 Word EssayDocument2 pagesAcademic Essays: Form and Function: The Structure of A 1000-3000 Word EssayNgô Hoàng Bích KhaNo ratings yet

- LanguagesDocument18 pagesLanguagesKHUSHI ANSARINo ratings yet

- Karnataka Class 10 English Solutions Chapter 1 A Wrong Man in Workers' Paradise - KSEEB SolutionsDocument19 pagesKarnataka Class 10 English Solutions Chapter 1 A Wrong Man in Workers' Paradise - KSEEB SolutionsS C Prajwal80% (5)

- Ni Luh Leoni Kartika (0176)Document3 pagesNi Luh Leoni Kartika (0176)leoni kartikaNo ratings yet

- Present Perfect and Simple Past ExerciseDocument10 pagesPresent Perfect and Simple Past ExerciseSimhadri MadhuriNo ratings yet

- Module 1 in ENG213DDocument9 pagesModule 1 in ENG213DLJSCNo ratings yet

- Translation As An ActivityDocument34 pagesTranslation As An ActivityGulasal HosinovaNo ratings yet

- Present Simple - Negative & QuestionsDocument5 pagesPresent Simple - Negative & QuestionsAna CruzNo ratings yet

- Comm Skills (Pasco) Prof KayDocument6 pagesComm Skills (Pasco) Prof KayChristopher ArthurNo ratings yet

- The Oxford English DictionaryDocument12 pagesThe Oxford English DictionaryMiguel Salvador Medina GervasioNo ratings yet

- Academy Stars 5 WB Unit 1Document9 pagesAcademy Stars 5 WB Unit 1Laura ChajturaNo ratings yet

- Verbs Noun Adjective AdverbDocument19 pagesVerbs Noun Adjective AdverbDariaNo ratings yet

- Hieroglyphs On Bone Ivory Tags of AbydosDocument6 pagesHieroglyphs On Bone Ivory Tags of AbydosSarah BernsdorffNo ratings yet

- Lgs Personal Lesson Plan 20-21 Half YearlyDocument3 pagesLgs Personal Lesson Plan 20-21 Half Yearlymasudur rahmanNo ratings yet

- There: It Generally Refers To Something Already Mentioned. There Is Used With BeDocument2 pagesThere: It Generally Refers To Something Already Mentioned. There Is Used With BeELENANo ratings yet

- Ovando, C.J. Et. Al. Bilingual & ESL Classrooms-Teaching in Multicultural ContextsDocument6 pagesOvando, C.J. Et. Al. Bilingual & ESL Classrooms-Teaching in Multicultural ContextsOlga KardashNo ratings yet

- Critical Reading Week 15 Assignment - Fathul Mubarak (19018059) K2-19Document3 pagesCritical Reading Week 15 Assignment - Fathul Mubarak (19018059) K2-19Fathul MubarakNo ratings yet

- Inglés II, Primera Edición, Yaneth Ocando Pereira - 1 - Unidad IDocument18 pagesInglés II, Primera Edición, Yaneth Ocando Pereira - 1 - Unidad IJhohanes OrtizNo ratings yet

- It's All Your Fault!: If You Had Filled The Car With Petrol, It Wouldn't Have Stopped!Document2 pagesIt's All Your Fault!: If You Had Filled The Car With Petrol, It Wouldn't Have Stopped!Predrag MaksimovicNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Language and SymbolsDocument4 pagesMathematical Language and SymbolsRachel Anne BodlisNo ratings yet

- Stylistic Classification of The English VocabularyDocument58 pagesStylistic Classification of The English VocabularyDiana ShevchukNo ratings yet